Latest Posts

CHICAGO (July 25, 2025) – The Chicago History Museum is excited to share it has acquired the collection of former Playboy Bunny/Playmate and Chicago media personality Candace Jordan thanks to funds provided by The Costume Council of the Chicago History Museum. These items add to the Museum’s large collection of Playboy-related material and contain a more personal history of Playboy in Chicago.

“These items are a great addition to our already incredible holdings surrounding the history of Playboy in Chicago,” said CHM costume collection manager Jessica Pushor. “Having an employee’s perspective, someone who worked in the clubs and for many other facets of the company, gives us a fuller picture of the importance Playboy played in the greater history of the city.”

This acquisition includes a complete Playboy Bunny of the Year costume, three sets of Bunny ears, trophies, a Playboy Mansion rule book and dozens of images and records related to Candace Jordan’s career with Playboy. Once the collection has been processed into the Museum’s collection, the 2D (paper) items will be available for scholars and researchers through the Museum’s Abakanowicz Research Center.

In 1973, Jordan first worked as a Bunny at the St. Louis Playboy Club before moving to Chicago in 1974. She worked at the original Playboy Club at 116 E. Walton Street, and for a time even lived at the Playboy Mansion at 1340 N. State Parkway. Jordan would go on to become the 1976 Chicago Bunny of the Year, the December 1979 centerfold and a nine-time Playboy cover girl. After leaving the mansion, she appeared in several films and commercials and continued her modeling career. Today she is an award-winning media personality in Chicago where she is a publisher with Chicago Star Media and a columnist. She also runs her own lifestyle blog (CandidCandace.com), podcast and YouTube channel.

###

ABOUT THE CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

The Chicago History Museum is situated on ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi people, who cared for the land until forced out by non-Native settlers. Established in 1856, the Museum is located at 1601 N. Clark Street in Lincoln Park, its third location. A major museum and research center for Chicago and U.S. history, the Chicago History Museum strives to be a destination for learning, inspiration, and civic engagement. Through dynamic exhibitions, tours, publications, special events and programming, the Museum connects people to Chicago’s history and to each other. The Museum collects and preserves millions of artifacts, documents, and images to assist in sharing Chicago stories. The Museum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chicago Park District on behalf of the people of Chicago.

PRIMARY SOURCE TYPE: PHOTOGRAPH, DOCUMENT, 2D OBJECTS

Recommended for grades 3-5

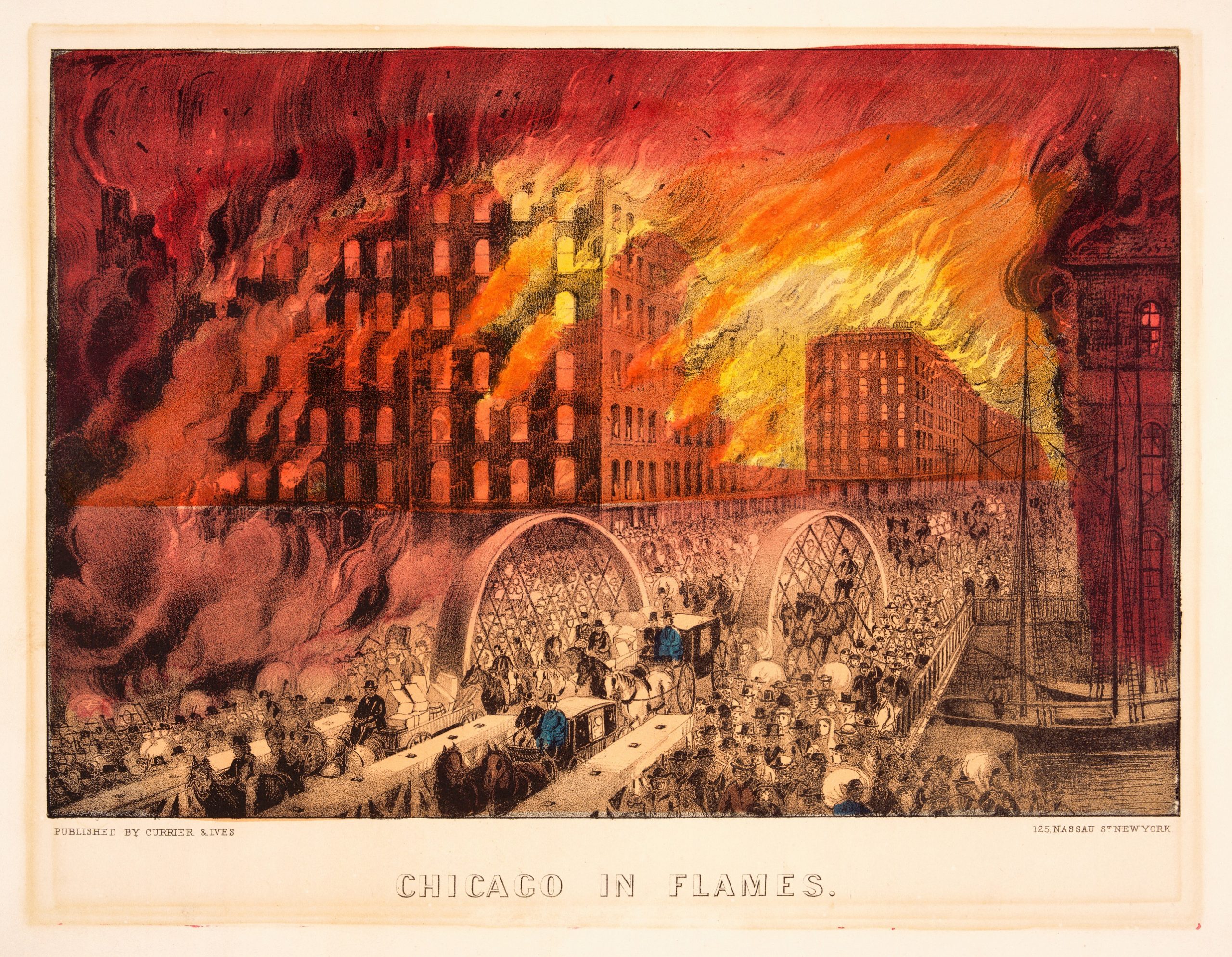

A rapidly growing city built of wood. A summer-long heat wave. An exhausted and misdirected team of firefighters. Racial, social, and economic tensions bubbling just below the surface—all Chicago needed was a spark. Our past exhibition City on Fire: Chicago 1871 was divided into four parts: pre-fire Chicago in the “Wooden City,” the three days of the fire in the “Burning City,” the immediate aftermath in the “Smoldering City,” and the recovery and rebuilding efforts in the “Rebuilt City.” This video series is designed to duplicate the four sections of the exhibition by examining key content with embedded activities for the classroom.

Each video has an English and Spanish version, narrated and captioned. All student handouts are bilingual, either side by side translation or split into separate single language worksheets.

CITY ON FIRE: THE WOODEN CITY

Running Time: 7 mins 45 secs (English); 8 mins 39 secs (Spanish)

The “Wooden City” introduces Chicago at the time of the fire, noting the factors that enabled the fire to spread rapidly through the city and the social tensions that later influenced recovery efforts. Activities can be used independently of each other, enabling educators to customize their classroom experiences.

Take Survey and Download Video

CITY ON FIRE: BURNING CITY

Running Time: 9 mins 57 secs (English); 10 mins 07 secs (Spanish)

The “Burning City” explores firefighting in 1871, the spread of the fire throughout the city, and how one Chicago couple, the Hudlins helped their neighbors. Activities can be used independently of each other, enabling educators to customize their classroom experiences.

Take Survey and Download Video

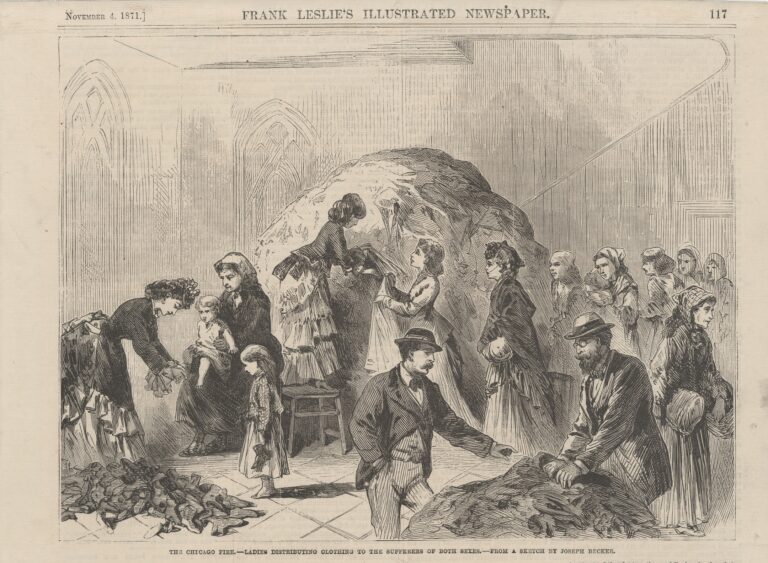

CITY ON FIRE: THE SMOLDERING CITY

Running Time: 6 mins 18 secs (English); 7 mins 17 secs (Spanish)

The “Smoldering City” introduces what happened in the immediate aftermath of the fire and the ways people remembered the Great Chicago Fire through collecting and saving objects, taking photographs, and creating paintings. Activities can be used independently of each other, enabling educators to customize their classroom experiences.

Take Survey and Download Video

CITY ON FIRE: REBUILT CITY

Running Time: 10 mins 42 secs (English); 11 mins 10 secs (Spanish)

The “Rebuilt City” encourages students to analyze drawings of post-Fire life, introduces how people navigated the post-Fire aid system through a questionnaire activity, returns to the story of Mrs. O’Leary, and examines fire safety today. Activities can be used independently of each other, enabling educators to customize their classroom experiences.

Take Survey and Download Video

PRIMARY SOURCE TYPE: 2D OBJECTS, DOCUMENT, PHOTOGRAPH

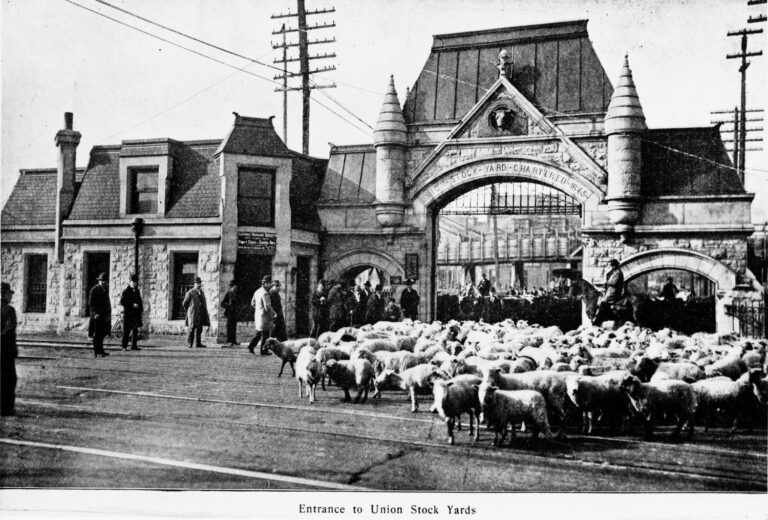

Recommended for grades 6-12

Running Time: 9 mins 27 secs

This video is based on the Stockyards section of Chicago: Crossroads of America. This video can be used as a stand-alone activity or prior to a CHM visit. Please note: Objects in the Museum rotate periodically, so artifacts featured in the video may not be currently on display.

This video takes a close look at how Chicago’s stockyards and meatpacking industries affected everything in the city from immigration and migration, to changing neighborhoods, to workplace safety, public policy and labor organizing. Students will be asked to consider these impacts, how work shapes a city, and what the future of work may look like in Chicago.

These additional resources support the use of this video in classroom instruction.

- Impacts of Stockyards and Meatpacking learning guide (PDF)

- Impacts of Stockyards and Meatpacking image packet (PDF)

- Video transcript in English (PDF) and Spanish (PDF)

PRIMARY SOURCE TYPE: PHOTOGRAPHS, DOCUMENTS, 2D OBJECTS

Recommended for grades 3-5

Running Time: 11 mins 20 secs

This video is based the Great Chicago Fire section of Chicago: Crossroads of America. This video can be used as a stand- alone activity or prior to a CHM visit. Please note: Objects in the Museum rotate periodically, so artifacts featured in the video may not be currently on display.

Students are asked critical thinking questions throughout this video as they discover not only the events of the three days of the fire but also consider how people were impacted and the sometimes unjust decisions made during the recovery efforts. Explore the lasting legacy of the fire and the lessons we can learn from the past when we face similar challenges today.

These additional resources support the use of this video in classroom instruction:

- Lessons from the Great Chicago Fire learning guide (PDF)

- Lessons from the Great Chicago Fire image packet (PDF)

- Video transcript in English (PDF) and Spanish (PDF)

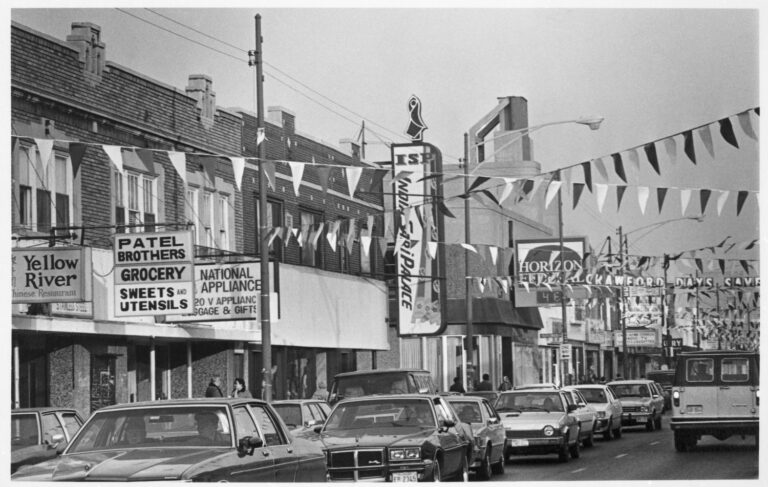

In this blog post, Anita Sharma, a graduate assistant in the Research & Access Department at CHM writes about photographer Mukul Roy and her work documenting the emergence of South Asian communities in Chicago.

In 1984, Indian American photographer Mukul Roy (1931–2023) gifted a portfolio of twenty-four black-and-white photographs to the Chicago History Museum (formerly the Chicago Historical Society). She references this gift in a rare interview conducted for the Asian American Oral History Project, led by DePaul University professor Laura Kina. The interview remains one of the few publicly accessible sources documenting Roy’s life and photographic practice.

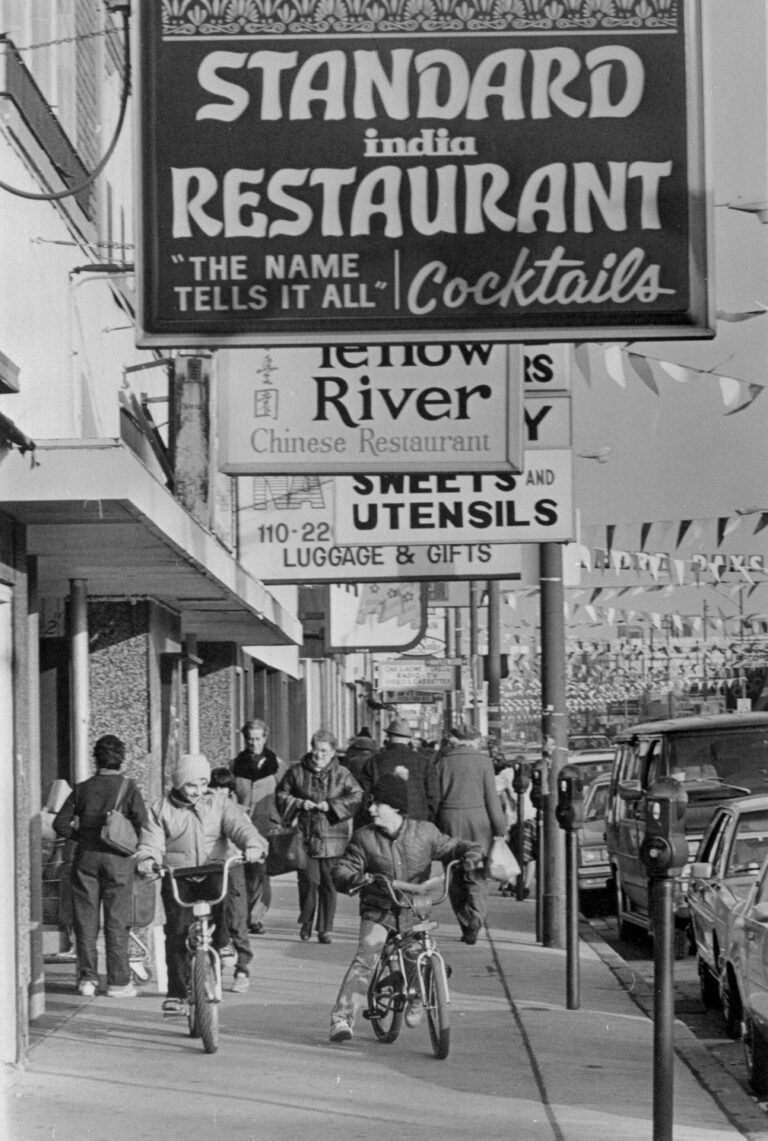

Devon Avenue near Maplewood Avenue, November 1984. CHM, ICHi-026078; Mukul Roy, photographer

Born in Udupi, in the Indian state of Karnataka, Roy spent her early years in India before moving to England with her husband in 1966. She immigrated to the United States in 1970 and settled in Chicago. Her photographic journey began in the early 1980s with the purchase of her first camera, an Instamatic bought with store coupons. At the time, photography was a way to navigate the cultural and language barriers she faced as a new immigrant. It became a tool of curiosity and connection, allowing her to relate to her surroundings and to the growing South Asian community around her. She later upgraded to a Nikon camera, took photography classes, and enrolled in a master’s program in photography at Columbia College Chicago.

Roy’s arrival in Chicago coincided with the first wave of South Asian immigration following the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. While detailed data from that period is limited, the Center for Immigration Studies notes that Illinois’s Asian population grew from 80,000 in 1970 to 302,000 by 1990. By 1980, roughly 35,000 South Asians were living in the Chicago metropolitan area. Roy’s photographs organically document this demographic shift, capturing the emergence of South Asian life across Chicagoland, especially along Devon Avenue in the West Ridge neighborhood. These images capture the emergence of South Asian diasporic space-making–how communities came together to build cultural familiarity and experience social connection.

Her 1984 portfolio captures Devon Avenue’s early South Asian-owned businesses and street life, including clothing shops, grocery stores, street food vendors, and restaurants. Among them was India Sari Palace, the first sari shop on Devon Avenue, which opened in 1973. Before its arrival, many South Asian women in Chicago ordered saris from Japanese mail-order catalogs. Roy recalled the challenges: “There were problems shopping by mail in selecting the patterns, and because of the long waiting period. A few months after the shop opened, Indian people crowded the store.” Selling imported synthetic saris from Japan, the store quickly became a cultural hub where women came not only to shop, but to gather and socialize.

Clerks and customers at Royal Sari Store, 2541 Devon Avenue, November 1984. CHM, ICHi-025787; Mukul Roy, photographer

When researching Devon Avenue and the emergence of South Asian communities in Chicago, Mukul Roy’s photographs almost always surface. She seemed to intuitively understand the long-term significance of documenting these everyday moments. At a time when there was little to no visual representation of South Asian life in the city, Roy turned her lens toward the people, businesses, and rhythms that would define a burgeoning diasporic community.

Devon Avenue is now synonymous with the iconic Patel Brothers supermarket, which opened its first location there in 1974 and later expanded across the United States. Roy’s photographs of the original Patel Brothers storefront are among the earliest visual records of this cultural landmark and are now frequently cited and reproduced in articles, exhibitions, and local histories of the area.

The owner’s son stocking shelves at Patel Brothers, 2542 Devon Avenue, Nov. 1984. CHM, ICHi-026012; Mukul Roy, photographer

Roy captures intimate moments of South Asian immigrants and families visiting Devon Avenue in search of the familiar—home-cooked food, hard to find spices, and a sense of belonging in a new environment. Her photographs show how local businesses became vital gathering spaces where families shared meals and reconnected with a wider community.

A family eating at Food and Flavor, 2559 Devon Avenue, December 1984. CHM, ICHi-025847; Mukul Roy, photographer

Standard India Restaurant on Devon Avenue. CHM, ICHi-025788; Mukul Roy, photographer

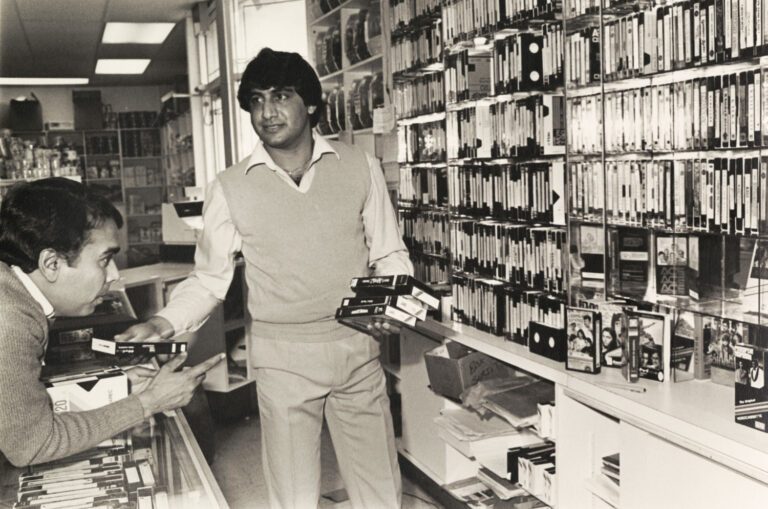

A familiar family pastime was renting popular Bollywood films from neighborhood grocery stores. These video kiosks were fixtures in South Asian supermarkets during the 1980s, offering a shared connection to home and culture for many newly arrived families.

Video rental kiosk at Food and Flavor, 2559 Devon Avenue, November 1984. CHM, ICHi-189095; Mukul Roy, photographer

In addition to her documentary work in Chicago, Roy developed a career as a freelance photojournalist. She contributed to publications such as India Tribune and the Chicago Tribune, and her assignments took her back to India. In 1984, she returned to India and photographed Prime Minister Indira Gandhi shortly before her assassination. That same year, she captured a memorial march held in Chicago in Gandhi’s honor. Roy also covered significant political moments, including White House visits by South Asian leaders and dignitaries.

Devon Avenue memorial march for Indira Gandhi, October 31, 1984. CHM, ICHi-061457; Mukul Roy, photographer

In the early 1990s, Mukul Roy held her first solo show, Asian Indians in Chicago, at the Chicago Cultural Center, organized by the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs. She also exhibited at Artemisia Gallery, an alternative art space active during that period. More recently, her work was featured in the archival exhibition What is Seen and Unseen: Mapping South Asian American Art in Chicago at the South Asia Institute in 2024.

Her Devon Avenue portfolio is housed in the collection of the Chicago History Museum and is also featured in the electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. These accomplishments highlight Roy’s important legacy in capturing and preserving early South Asian diasporic history in Chicago.

The rest of CHM’s collection of Roy’s photographs can be viewed at the Abakanowicz Research Center during regular research hours.

Related Event

- Learn more about the history and legacy of Devon Avenue through Timeline Theatre’s play Dhaba on Devon Avenue, which runs through July 27, 2025. CHM members get $10 off up to 4 regular price tickets. Contact Hannah Johnson, member relations manager, at hjohnson@chicagohistory.org for details.

Bibliography

- Emily Eller, Mukul Roy Interview, 2011.

- “Indians,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, Chicago Historical Society.

- Maria Nilsson, “Passionate Explorer: An Inquisitive Mind Pushes Past Cultural Barriers,” Chicago Tribune, July 29, 1990.

- Ilana A. Rodriguez, “Devon Avenue Is a Feast for the Senses—and the Soul—of Chicago’s South Asian Community,” Chicago Sun-Times, November 25, 2022.

- Mukul Roy, portfolio of Indian Immigrants, 24 photographic prints, black-and-white, 1984, Chicago History Museum Collection.

- South Asian American Policy & Research Institute, Making Data Count: South Asian Americans in the 2010 Census with Focus on Illinois (Chicago: SAAPRI, 2013).

- Jie Zong and Jeanne Batalova, “Indian Immigrants in the United States,” Migration Policy Institute, August 31, 2017.

CHICAGO (June 17, 2025) – There are only a few weeks left to see “Dressed in History: A Costume Collection Retrospective” at the Chicago History Museum. Closing on July 27, the exhibition celebrates major milestones and acquisitions for its costume collection and the Costume Council’s history and offers guests an exclusive look at dozens of extraordinary objects, including some that have never been displayed. Through the exhibition, visitors can explore how clothing captures material, social and changing cultural values throughout history.

“Seeing the physical fashion pieces rather than just photos enhanced the experience for us,” said one guest after their visit. “We loved getting to see pieces from a wide range of times and a diverse range of designers. Fashion is so entwined with history, and the exhibition does a fabulous job showing that.”

Featuring more than 70 artifacts, “Dressed in History” is an eclectic mix of garments and accessories representing men’s, women’s and children’s clothing that spans from couture ensembles to home-sewn items. The exhibition highlights the long and rich history of fashion, manufacturing, and retail that has been part of the city’s identity for nearly 200 years. The gallery is divided into four different sections: Everyday/Sportswear, Couture & Designer, Historic Dress, and Art & Fashion. Within the space, guests see a range of artifacts from a Christian Dior gown to a baby’s wool bathing suit.

“Clothing is an artifact all of us can relate to, and Chicagoans have a long history with fashion as consumers, retailers, designers, and manufacturers,” says exhibition curator, Jessica Pushor. “From the birthplace of mail-order catalogs to the large garment manufacturing industry from 1880 to the 1920s, Chicago has had a major impact on fashion history and continues to do so through the city’s design schools, local designers who call Chicago home and retail establishments. We hope visitors leave the exhibition with a better understanding of the holdings in our costume collection and the intriguing stories these objects can tell.”

For more information, please visit the Chicago History Museum’s website or contact the Museum’s press office.

Media kit available here: https://chicagohistory.box.com/s/b5qfpiukm7fu8zob5k1dhxajkkplu7ce

###

ABOUT THE CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

The Chicago History Museum is situated on ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi people, who cared for the land until forced out by non-Native settlers. Established in 1856, the Museum is located at 1601 N. Clark Street in Lincoln Park, its third location. A major museum and research center for Chicago and U.S. history, the Chicago History Museum strives to be a destination for learning, inspiration, and civic engagement. Through dynamic exhibitions, tours, publications, special events and programming, the Museum connects people to Chicago’s history and to each other. The Museum collects and preserves millions of artifacts, documents, and images to assist in sharing Chicago stories. The Museum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chicago Park District on behalf of the people of Chicago.

CHICAGO (June 12, 2025) – This summer, Civic Season returns to the Chicago History Museum with a series of exciting and informative programs focused on learning from Chicago’s past to write a better future. Presented in partnership with Made By Us, CHM collaborates with local community leaders, artists, and youth to set the stage every summer for Civic Season. Programming starts on Juneteenth and continues with Civic Saturdays all leading toward the final program on Independence Day.

“There is a myriad of people who have made the promises of our nation tangible over time, but their stories aren’t always known or fully understood. Using the past as a guide, we can draw a roadmap to future community participation so we may all be more informed and engaged citizens,” said Erica Griffin-Fabicon, Elizabeth F. Cheney Director of Education at the Chicago History Museum.

This year, presented in collaboration with the Floating Museum, CHM is hosting the “Founders” inflatable sculpture at the Museum on June 21, 2025, in support of Civic Season and to further promote awareness of underrepresented parts of Chicago’s history. During the program, the mobile monument will be further activated with performances and related hands-on arts-making activities for youth and families.

Civic Season Programming

Celebrating Juneteenth with The DuSable Black History Museum and Education

Thursday, June 19, 8 a.m.–8 p.m.

Join CHM at the DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center for their annual Community BBQ where guests will enjoy a vibrant mix of education, entertainment, food and local vendors as we honor Black history, culture and freedom. Learn more here.

Civic Saturdays

Saturdays, June 21 & June 28, 10 a.m.–4 p.m.

Join CHM to explore the city’s civic legacy and explore ways to transform ideas into action through workshops, tours, art projects and documentaries about today’s issues. Leave with skills, connections and a roadmap for making real change.

Independence Day: Shaping Chicago’s Next Chapter

Friday, July 4, 10 a.m.–4 p.m.

What actions will you take to be a more engaged citizen? How will you stay informed about issues affecting your community? Find inspiration, connect with community-serving organizations and explore your creativity with multiple civic art workshops. Together, we’re learning from the past to write a better future. What will your chapter add to Chicago’s story?

During the events, guests will hear from civic leaders including Tonika Johnson, Folded Map Project; Shermann “Dilla” Thomas, Chicago Mahogany Tours; and Mikva Challenge. There will also be numerous opportunities for hands-on activities including outdoor games and facepainting, button-making, swag giveaways, trivia contests and more.

All Civic Season events are free admission days to CHM for Illinois residents. Learn more about the series of programs here.

Civic Season is celebrated nationally by more than 300 cultural institutions and museums gearing up to 2026, which will mark the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Join us to lay the groundwork for a meaningful, vibrant commemoration for all with empowering and resonant opportunities to contribute to the American story.

###

ABOUT THE CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

The Chicago History Museum is situated on ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi people, who cared for the land until forced out by non-Native settlers. Established in 1856, the Museum is located at 1601 N. Clark Street in Lincoln Park, its third location. A major museum and research center for Chicago and U.S. history, the Chicago History Museum strives to be a destination for learning, inspiration, and civic engagement. Through dynamic exhibitions, tours, publications, special events and programming, the Museum connects people to Chicago’s history and to each other. The Museum collects and preserves millions of artifacts, documents, and images to assist in sharing Chicago stories. The Museum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chicago Park District on behalf of the people of Chicago.

CHICAGO (May 30, 2025) – The Chicago History Museum is proud to announce the honorees for the 2025 Making History Awards. This prestigious event celebrates the outstanding achievements of individuals and corporations who have made a lasting impact on the city of Chicago.

Over the past 30 years, we have honored 151 individuals from all walks of life for their enduring contributions to art and culture, sports, business and civic life. We have also celebrated 13 companies for their historic corporate achievements.

The distinguished honorees at the 2025 Making History Awards are:

- Martin Cabrera Jr., CEO & Founder of Cabrera Capital, receiving the Marshall Field Making History Award for Distinction in Corporate Leadership and Innovation

- Susan Crown, Founder and Chairman of the Susan Crown Exchange, receiving the Daniel H. Burnham Making History Award for Distinction in Visionary Leadership

- Hon. Rahm Emanuel, Former U.S. Ambassador to Japan and Former Mayor of the City of Chicago, receiving the Harold Washington Making History Award for Distinction in Public Service

- Steppenwolf Theatre, a Chicago theater company, receiving the Theodore Thomas Making History Award for Distinction in the Performing Arts; Audrey Francis, Artistic Director, and Brooke Flanagan, Executive Director, will accept the award

The award ceremony will take place on Wednesday, June 4, 2025, at 6 p.m. at the Four Seasons Hotel Chicago. Attendees will have the opportunity to hear the unique stories of each honoree and gain insight from their esteemed colleagues on the significance of their contributions to the community. The event will also feature speeches from Chicago History Museum leadership and provide an overview of the Museum’s current initiatives and exhibitions.

The Chicago History Museum inaugurated this event in 1995 to provide vital financial support to the Museum’s operations and programs. More than three decades later, this event is still a cornerstone of the institution, supporting the Museum’s mission to serve as the primary destination for learning, inspiration and civic engagement to connect people to Chicago’s history and each other.

For more information on supporting or attending the Making History Awards, please contact Eric Miller, Development Coordinator, at miller@chicagohistory.org or (312) 799-2110.

The press kit can be found here: https://chicagohistory.box.com/s/ll08hwsf55bzfy6h7zb0jfktqj75bude

###

ABOUT THE CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

The Chicago History Museum is situated on ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi people, who cared for the land until forced out by non-Native settlers. Established in 1856, the Museum is located at 1601 N. Clark Street in Lincoln Park, its third location. A major museum and research center for Chicago and U.S. history, the Chicago History Museum strives to be a destination for learning, inspiration, and civic engagement. Through dynamic exhibitions, tours, publications, special events and programming, the Museum connects people to Chicago’s history and to each other. The Museum collects and preserves millions of artifacts, documents, and images to assist in sharing Chicago stories. The Museum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chicago Park District on behalf of the people of Chicago.

In Chicago, there are neighborhoods, community areas, and wards, and each term has a distinct meaning. CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman explains the differences, why these distinctions exist, and how they change over time, a key theme explored in our upcoming exhibition Aquí en Chicago.

What is a community, and is that the same as a neighborhood? Chicago’s identity as a “city of neighborhoods” implies there would be some way of defining what these neighborhoods are, what that means for Chicagoans living here, and how they create our sense of community. And yet, there are countless ways to think about and draw boundaries around how we could divide and subdivide the city. This could be based on where you live, what businesses you visit, or where your place of work or place of worship is located. It can also be a feeling, somewhere you consider a home, the spaces you walk by every day, the street corners you recognize, where your friends live.

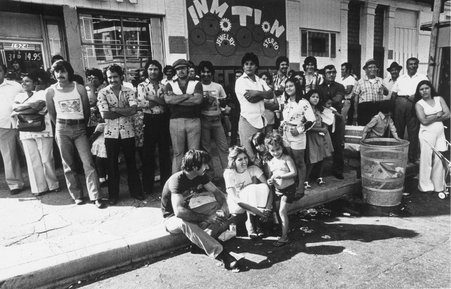

Fiesta del Sol in the Pilsen neighborhood, Chicago, August 1978. CHM, ICHi-031836

When discussing neighborhoods, it is important to think about how there is the idea of a neighborhood, a concept recently re-explored again by the Chicago Neighborhoods Project, and a physical or political boundary used for a specific purpose. In this latter sense, Chicago is often divided in three main ways: neighborhoods, community areas, and wards.

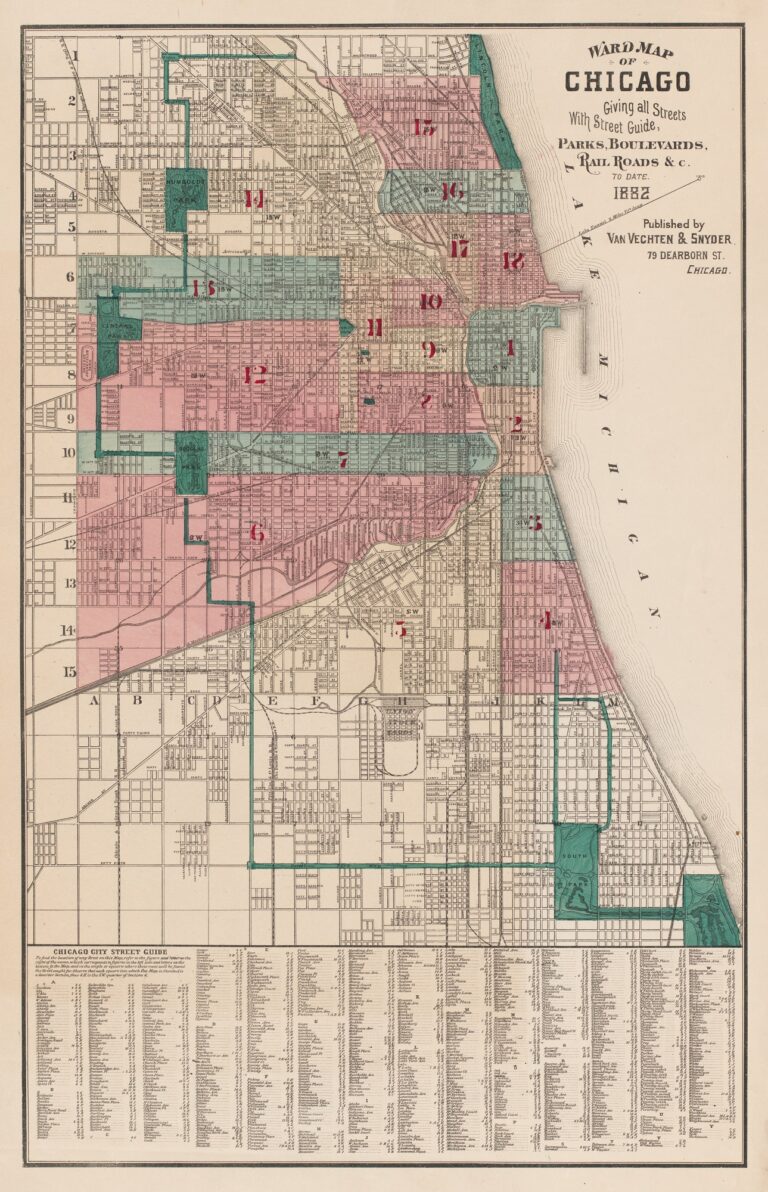

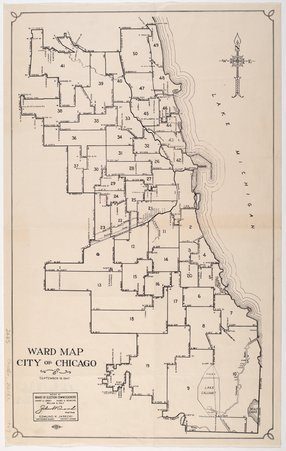

(L) Ward map of the City of Chicago, 1882. CHM, ICHi-092878

(R) Ward map for the City of Chicago, September 19. 1947. CHM, ICHi-173823

Wards relate directly to politics. The City of Chicago is divided into 50 voting districts, or wards, that in turn establish 50 City Council seats. These are meant to be essentially of equal size based on population, with each ward currently holding ~53,900 residents on average. The boundaries of wards can change based on information collected in the census every ten years through a process called redistricting.

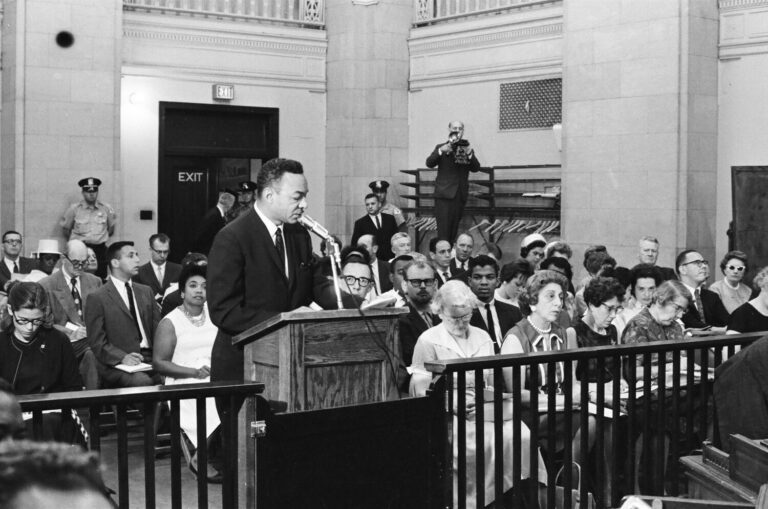

Members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) speak to the Board of Education on issues of segregation in schools and gerrymandered school district lines. July 30, 1963, ST-60002620-0034, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Redrawing the ward maps can be a fraught and opaque process. For example, new district lines are proposed through an ordinance, which is a verbal description of the locational boundaries proposed, not an actual physical map. Additionally, gerrymandering, or the political manipulation of these boundaries, can create deep inequities by dividing communities into multiple wards making cohesive economic and social stability ongoing challenges.

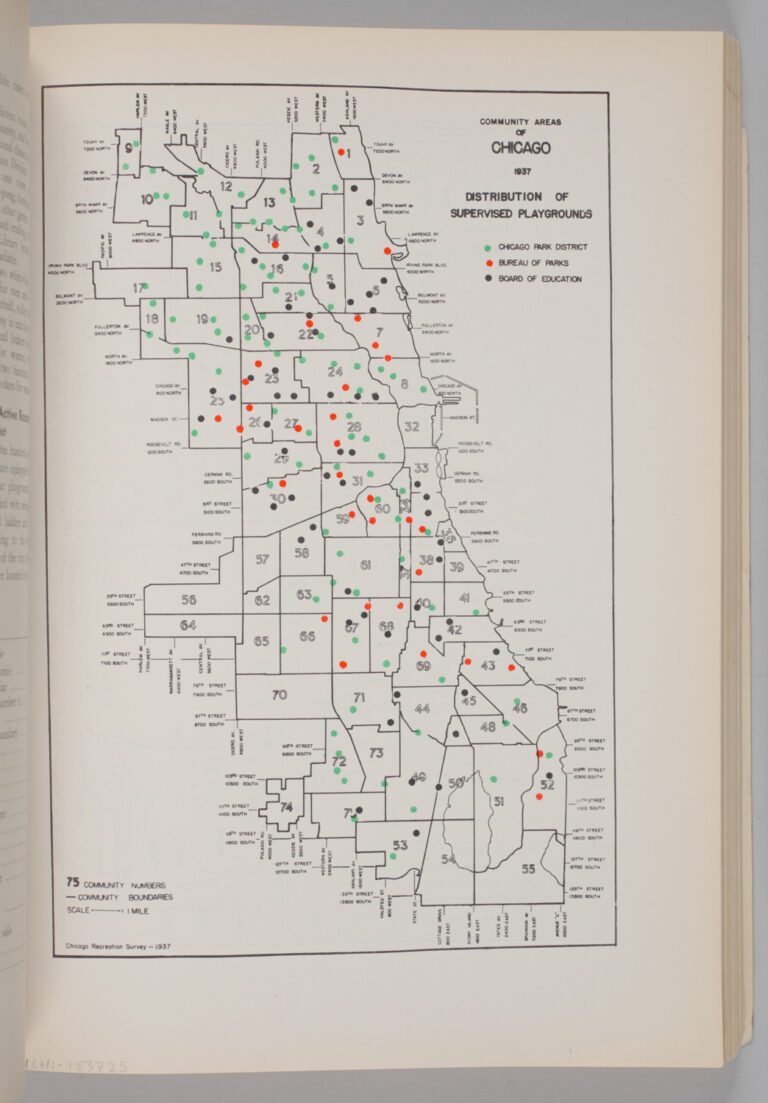

Community Areas of Chicago 1937: Distribution of Supervised Playgrounds, p. 105, 1937. CHM, ICHi-183725; Chicago Recreation Commision, author

When we say communities, as in the opening paragraph above, this can mean a lot of things—be it living in the same place, having similar interests or hobbies, sharing aspects of a cultural identity, and much more. However, “community” in Chicago also refers to the city’s officially defined community areas. Unlike neighborhoods, these are fixed divisions—each having roughly the same population within. In the late 1920s, Robert Park and Ernest Burgess mapped 75 community areas in Chicago based on information from the US Census Bureau, the boundaries for which are still largely unchanged. A small exception is the later additions of O’Hare (1956) and Edgewater (1980) to make the 77 community areas we know and use today. Areas were carefully delineated based on statistics like income, crime rates, and health information. These unchanging boundaries have proved useful for planning and studying purposes.

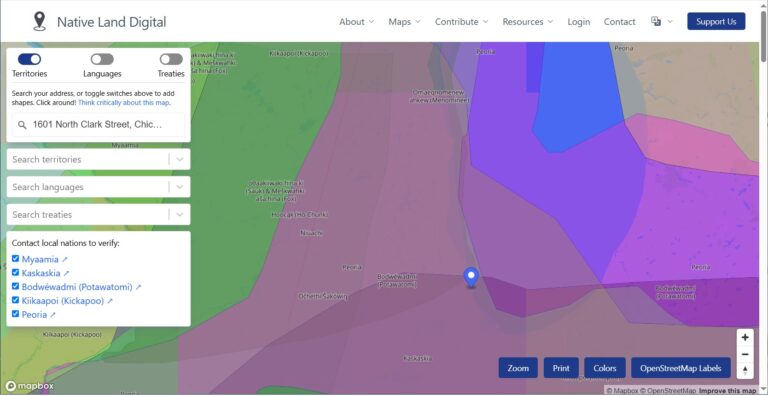

Map data provided by Native Land Digital. Used with permission for educational and non-commercial purposes.

However, they are not a full representation of how Chicagoans perceive the city nor how they define the places in which they live. An “area” is not the same as having a defined space for community or a space of belonging. Additionally, there are countless ways of conceptually thinking of one’s relationship to space and land relationally and fluidly. For example, the Native Land Digital map demonstrates ways to conceive of the Zhegagoynak/Zhigaagon/Zaagawaang/šikaakonki (Chicago) area through language, tribal territories, and treaties in stark contrast to the gridded system we see in most area maps.

A 2021 study on the concept of belonging and cultural institutions importantly notes that people who identify as Black, Latino/a/e, and Asian more often describe community through race or ethnicity, and people who identify as white more often think of community as a place or location. This closely relates to the idea of a “neighborhood,” which is conceptually and practically much more fluid and subjective than a geopolitically defined community area. Neighborhood boundaries and understanding of identity change through time and, for many Chicagoans, drive a stronger sense of place than a community area. Chicago neighborhoods are constantly changing in name and delineation, and today the city boasts more than 200 distinct neighborhoods, each holding claim to a sense of individual identity and local pride.

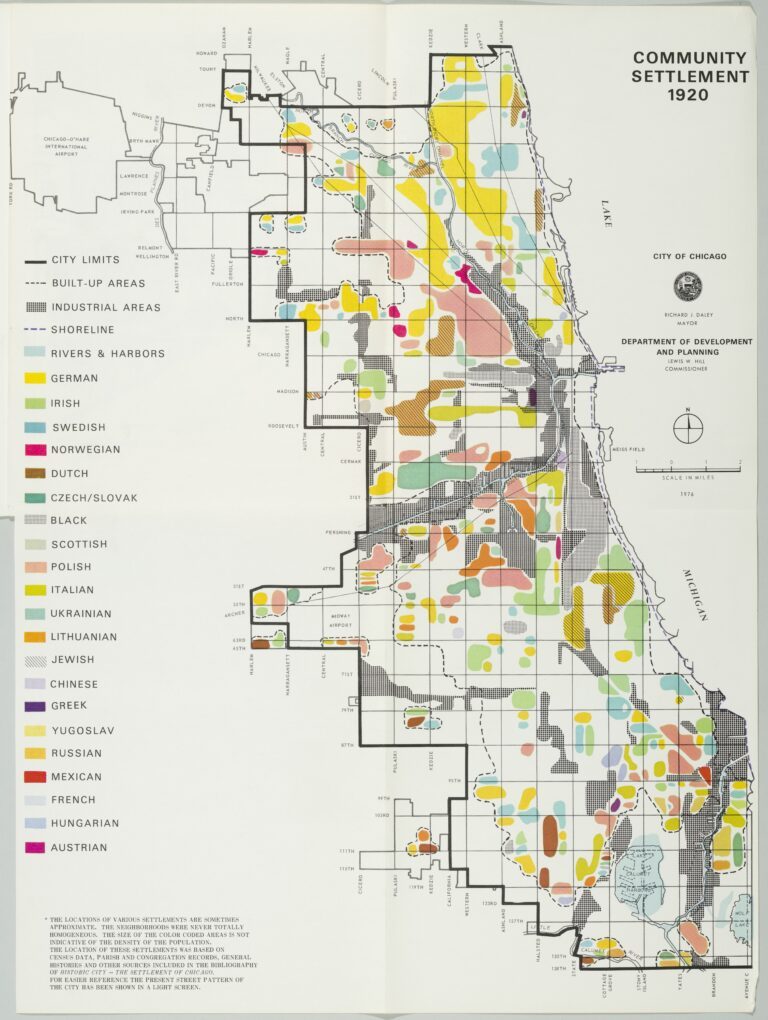

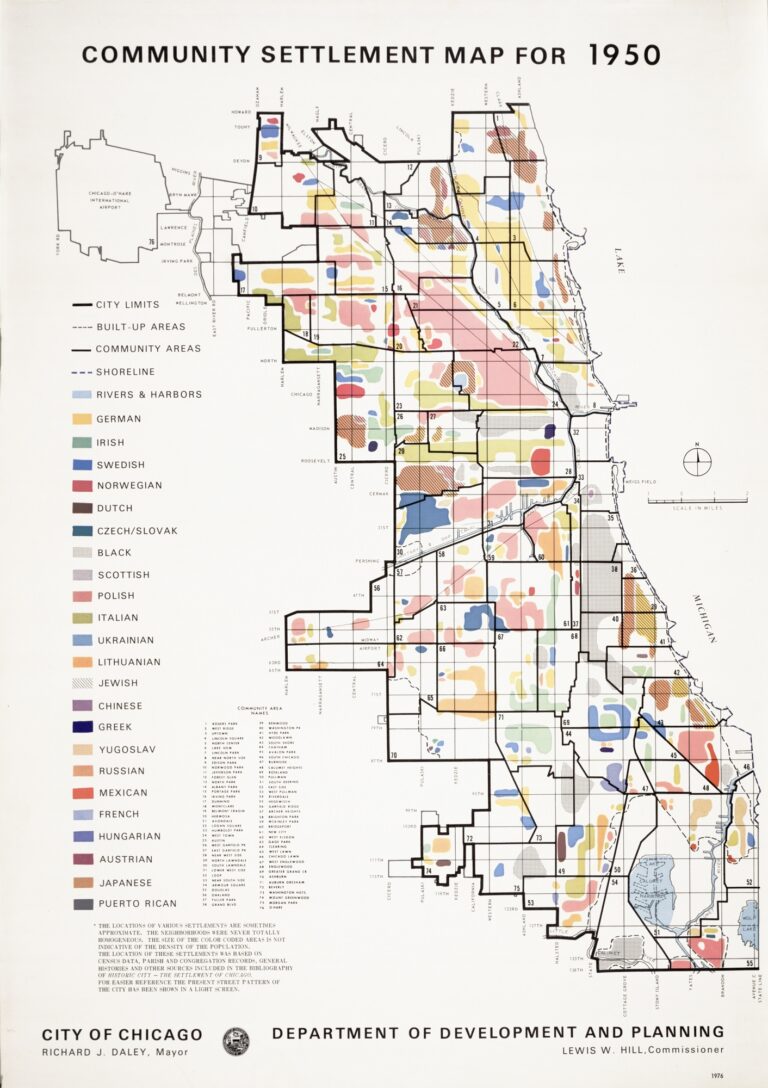

Community Settlement Map for 1920 and 1950 based on race and ethnicity, produced by the City of Chicago Department of Development and Planning, 1976, CHM, ICHi-182192 and ICHi-051194

Seeing Chicago as a city of neighborhoods often goes hand-in-hand with its “multiethnic” identity. This is generally thought of in terms of migration and how communities of different nationalities, ethnicities, races, and languages created space for themselves in the city. Henry C. Binford called this “multicentered Chicago,” arguing that the idea of a “neighborhood” is a vague and contested concept. Instead, Binford claimed we should look at the city as a series of “spatial subcommunities” that have innumerable instances of human interaction and diverse histories.

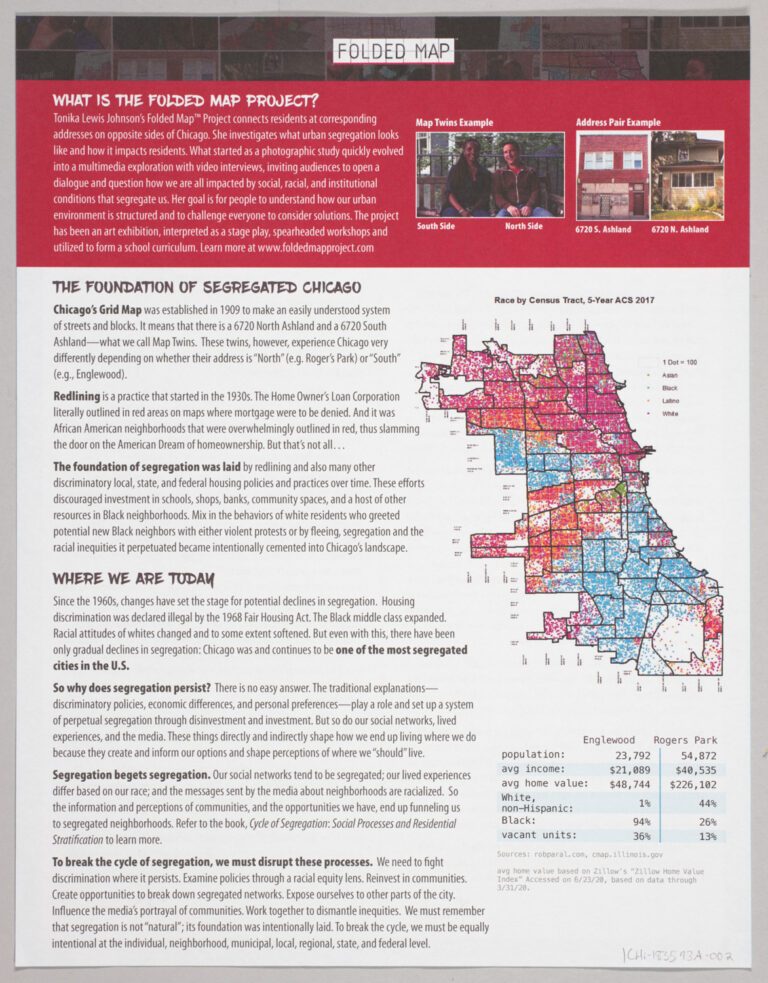

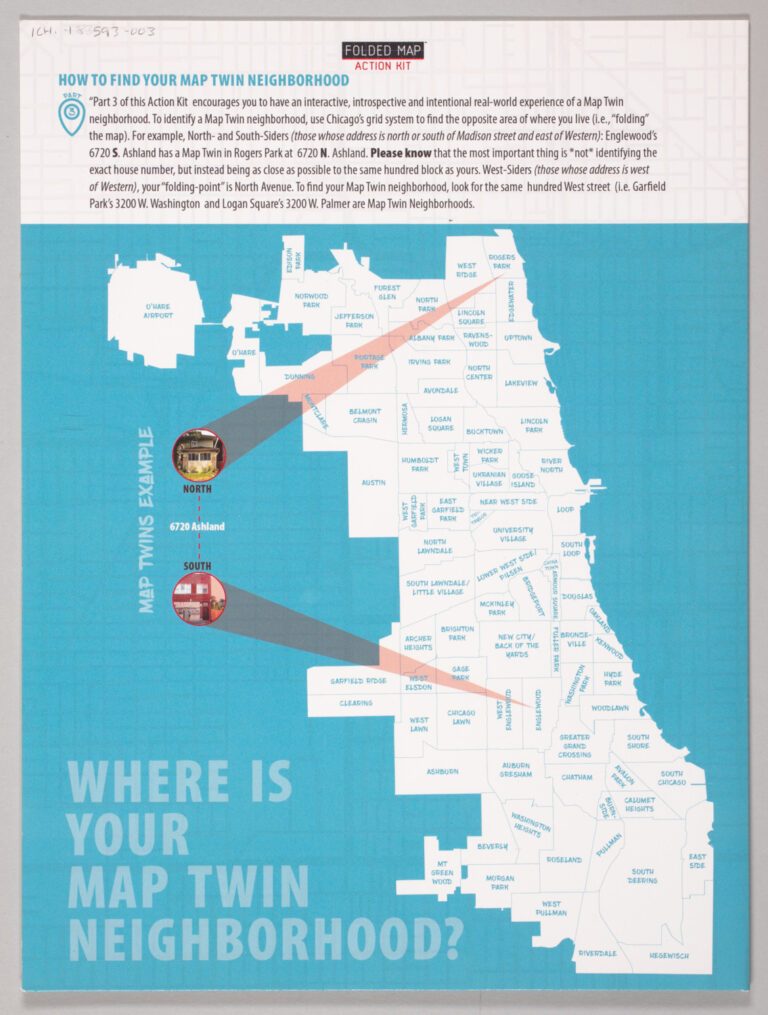

Two pages from the Folded Map Action Kit, a project to connect people living on the North and South Sides of Chicago with each other using the grid street address system to highlight disparities between neighborhoods. Folded Map © 2020, Tonika Lewis Johnson and Maria Krysan. All rights reserved. Kit design by JNJ Creative, LLC; CHM, ICHi-183593A-002, ICHi-183593-003

A related spatial legacy is Chicago’s identity as one of the most segregated cities in the US. In Chicago, segregation has been notably decreasing, and yet it remains the fourth most segregated city in the country, according to data from 2019. These recent studies also show that for many cities across the country, segregation is growing, not declining, with the Midwest disproportionately represented.

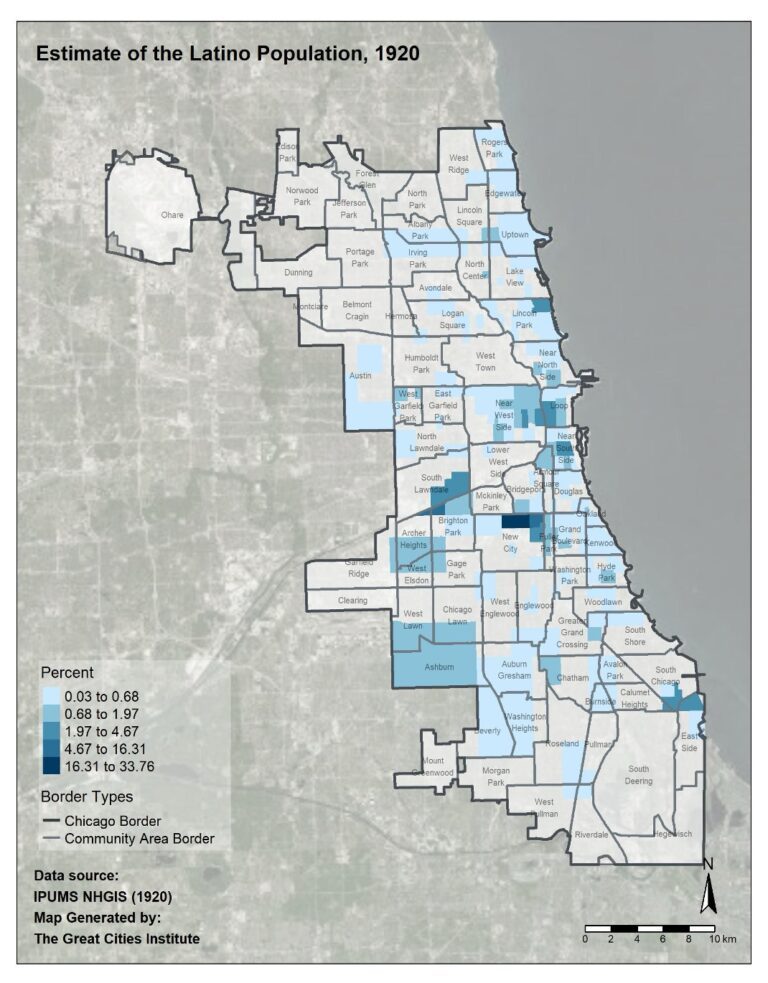

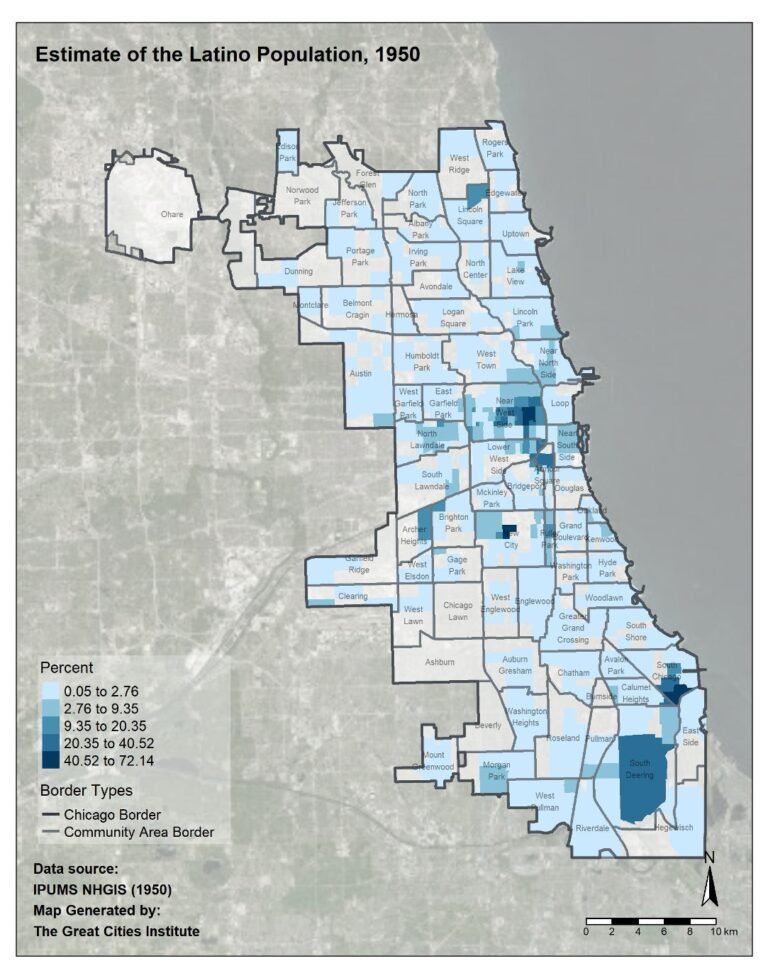

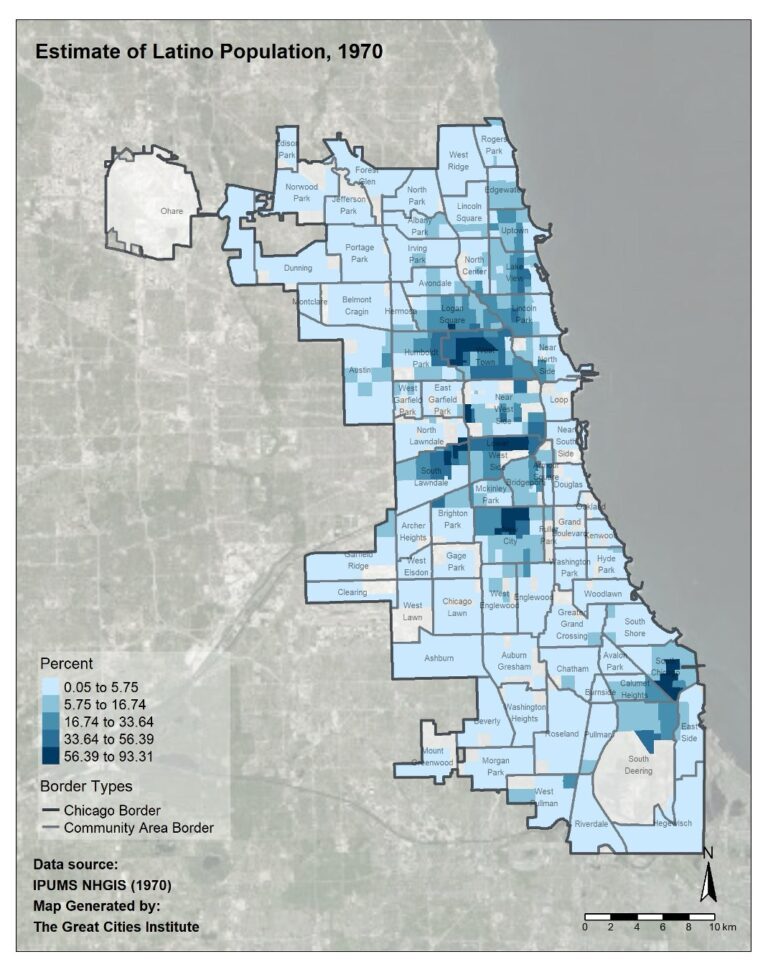

Maps depicting the “Estimate of the Latino Population” in Chicago, 1920, 1950, and 1970. Maps courtesy of Great Cities Institute at University of Illinois Chicago

In the context of Aquí en Chicago, we think about how communities make space for themselves in the city through many ways, including neighborhoods that Latino/a/e communities strongly identify with or have historically called home. These three maps come from a series of maps created by the Great Cities Institute at the University of Illinois Chicago for Aquí en Chicago. They show the demographic distribution of Latino/a/e people across Chicago through time and the evolution of making space from core neighborhoods in the 1920s such as the Southeast Side, Calumet, Back of the Yards, and East Chicago (known as the colonias) to Latino/a/e presence in nearly every part of the city and broader suburban Chicagolandia today.

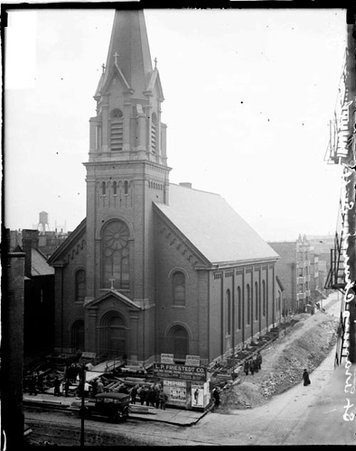

St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church on the Near West side is an example of ethnic succession, built for the German and German American community and later became Latino/a/e majority in attendance.

(L) St. Francis of Assisi Church, 813 W. Roosevelt Rd., Chicago, 1917. DN-0067872, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, CHM

(R) Exterior view of J. J. Strnad Real Estate with a sign advertising in Spanish and English, 1801 Blue Island Ave., Chicago, January 8, 1961. CHM, ICHi-051411; John McCarthy, photographer

Key to this idea of Latino/a/e neighborhoods is the concept of ethnic succession, in which different ethnic or racial communities occupy different places through time. When we consider evolving neighborhood identities, we see how shifts in elements like who sees themselves as represented in the neighborhood, what are the community anchors, whose image is on the advertisements, and what language is on the business signs, all combine to create a sense of place. That place, that sense of belonging, creates a sense of identity. As this shifts through time, communities, in turn, feel like a sense of ownership may shift as well.

Residents protest the designation of the area around Halsted and Harrison Streets as the site of the new University of Illinois campus, March 19, 1961, ST-17600243, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM

These ethnic shifts do not happen in a vacuum of neutral migration and movement by families and communities. Urban renewal, economic displacement, forced migration, racial segregation, and gentrification are key driving factors for how and why neighborhoods may shift over time. For example, in the 1950s and ’60s, thousands of people were displaced to make way for the Eisenhower Expressway and the University of Chicago Circle Campus. Neighborhoods like Pilsen (as part of the Lower West Side community area) and Little Village (as part of the South Lawndale community area) shifted from being predominantly European residents (in this case, Czech and Polish) to Latino/a/e. Communities make and keep places, in many ways and for many different reasons, defining and making Chicago (and beyond) the city we know today.

In 1925, the inaugural Woman’s World’s Fair was held April 18–25 in the American Exposition Palace. It attracted more than 160,000 visitors and consisted of 280 booths representing 100 occupations in which women were engaged.

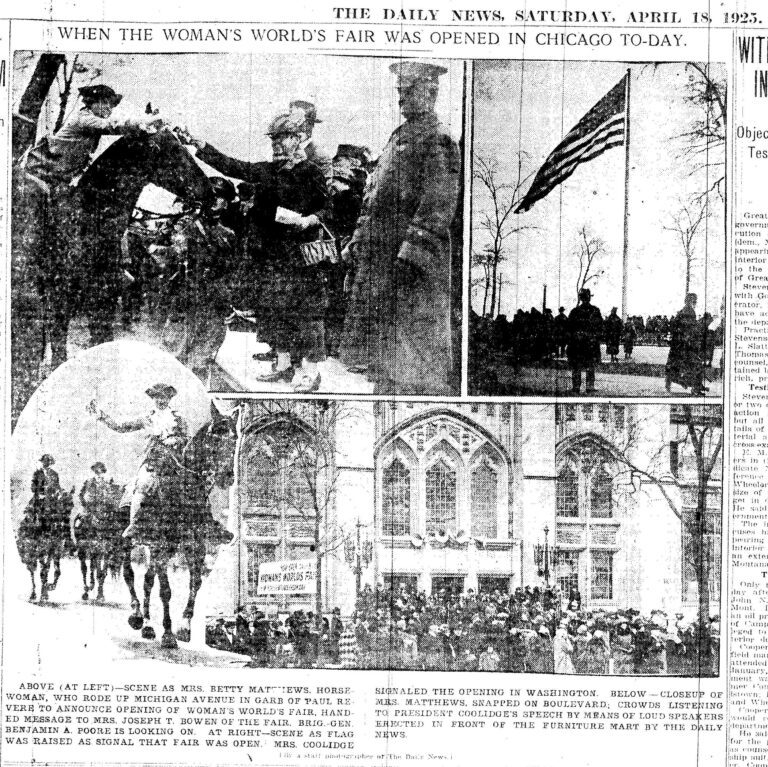

News coverage of the opening showed “Mrs. Betty Matthews, horsewoman, who rode up Michigan Avenue in garb of Paul Revere” on the left, a flag raising that signaled the fair’s opening, and a crowd listening to President Calvin Coolidge’s speech, Chicago Daily News, April 19, 1925, p. 3.

The fair was the idea of Helen Bennett, the manager of the Chicago Collegiate Bureau of Occupations, and Ruth Hanna McCormick, a leading clubwoman and Republican politician.

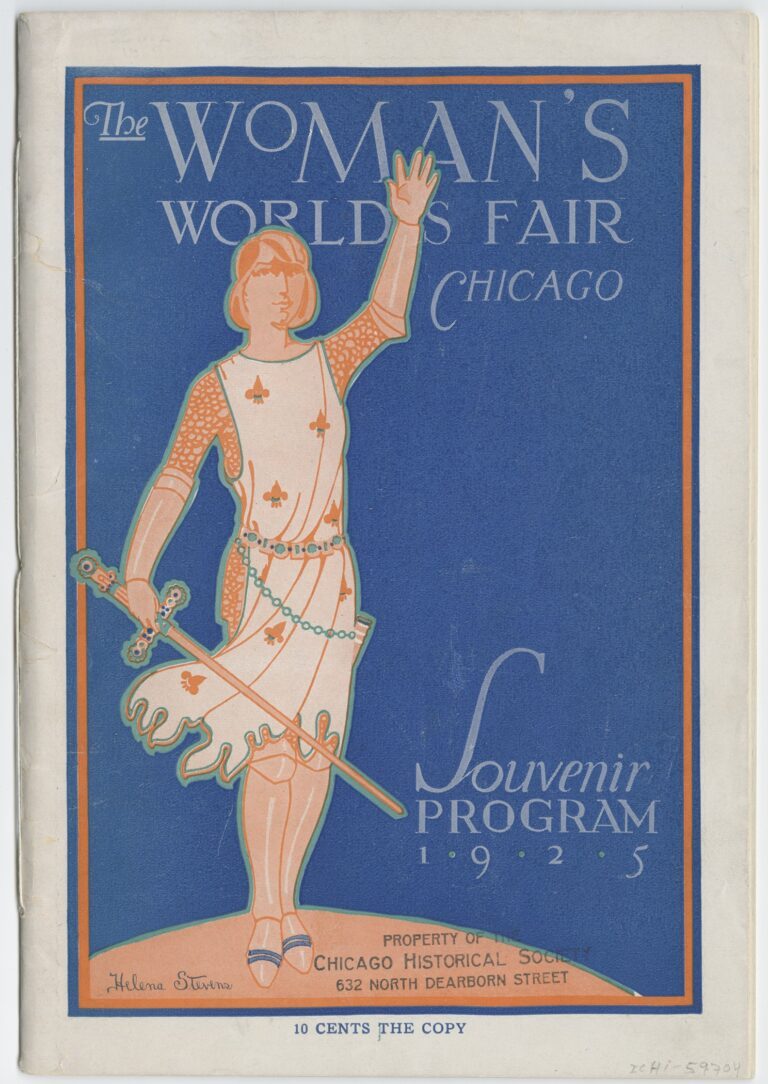

Cover page of The Woman’s World’s Fair souvenir program, 1925. HQ1106 .W6 1925. CHM, ICHi-037941

It was, in part, inspired by the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and initiatives such as the Woman’s Building. However, it was also a response to the unequal representation and lack of visibility some women experienced in 1893. Women organizers publicized and ran the fair; its managers and board of directors were all women.

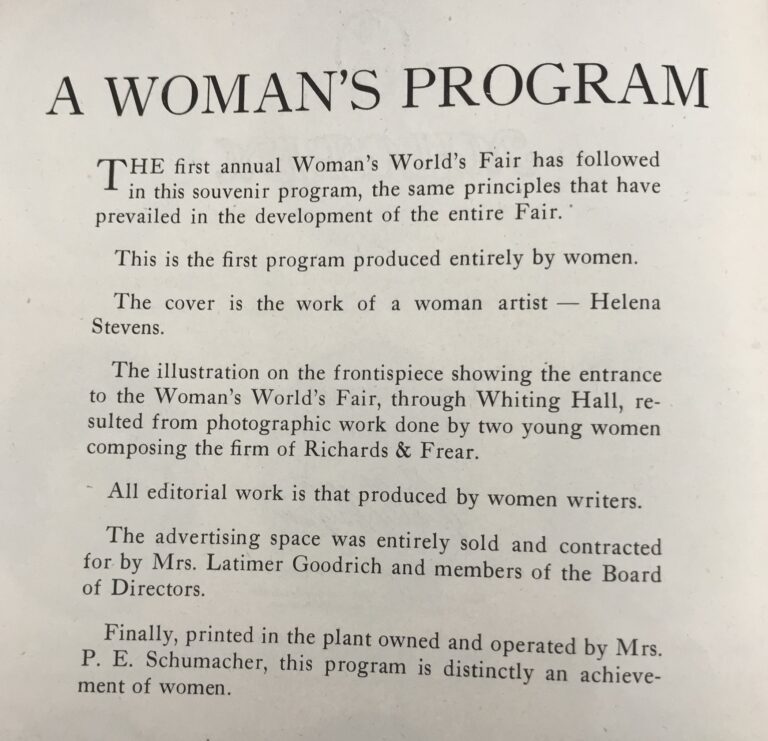

The souvenir program was also entirely produced by women. Photograph by CHM staff

The fair had the double purpose of displaying women’s ideas, work, and products, and raising funds to help support women’s Republican Party organizations. The booths at the fair showed women’s accomplishments in the arts, literature, science, and industry. These exhibits were also intended as a source for young women seeking information on careers.

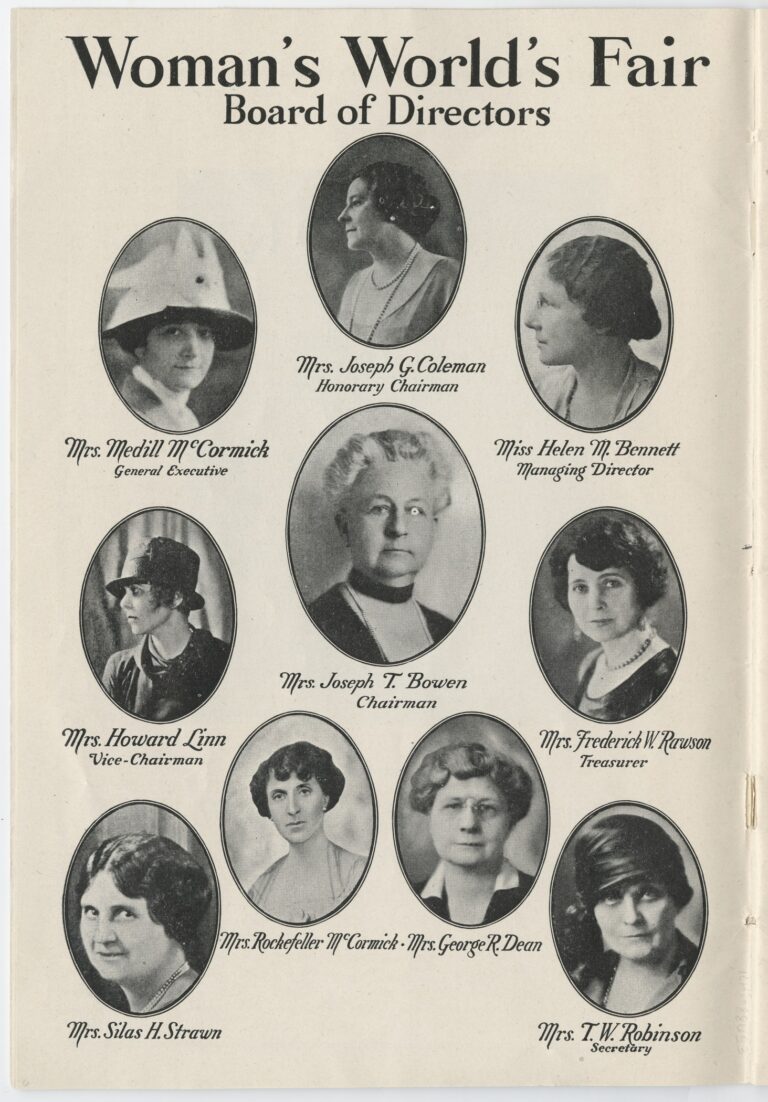

Portraits featuring the Woman’s World’s Fair Board of Directors from page 6 of The Woman’s World’s Fair souvenir program, 1925. HQ1106 .W6 1925. CHM, ICHi-088653

Among the exhibitors at the fair were major corporations, such as Illinois Bell Telephone Company and the major national and regional newspapers. Local manufacturers, banks, stores, and shops, area hospitals, and women inventors, artists, and lawyers set up booths demonstrating women’s contributions in these fields and possibilities for employment. Women’s groups were represented by such organizations as the Women’s Trade Union League, Business and Professional Women’s Club, the Visiting Nurse Association, the YWCA, Hull-House, the Illinois Club for Catholic Women, and the Auxiliary House of the Good Shepherd.

From left, seated: Mrs. Joseph T. Bowen, Gov. Nellie Tayloe Ross, Judge Katherine Sellers, Cyrena Van Gordon, Dr. Helen M. Strong. From left, standing: Mrs. Radford Warren, Mrs. Mabel Reinecke, Miss Lucia Briggs, Fannie Ferber Fox, Paulina Palmer, Mrs. Lois Pierce Hughes, Chicago Daily News, April 24, 1925, p. 5.

The 1925 fair raised $50,000 and was so successful that it was held for three more years.

It should be noted that the Woman’s World’s Fair of 1925 came in the wake of two major events. In the summer of 1919, tensions in the city were high after the racially motivated drowning of Eugene Williams, an African American teenager, in Lake Michigan and ensuing violence and deaths of both Euro-American and African American Chicagoans.

That same year, the US Congress passed the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote. The suffragist movement also saw racial tensions, as white organizers would exclude or segregate African American and other women of color from their marches and other efforts. Nevertheless, the resolution’s ratification in 1920 became a watershed moment for women’s rights and radically shifted the national political climate forever.

On the one hand, women asserted their right to be recognized and uplifted through dedicated events of their design. On the other hand, while some strides were made in more racially diverse representation, inequality persisted.

Additional Resources

- View our online exhibition Democracy Limited: Chicago Women & the Vote, which invites visitors to explore women’s activism in Chicago to secure the right to vote—and beyond.

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s interviews with many of the leading advocates of feminism and women’s rights in the mid to late 20th century.

- Peruse our Women’s Studies LibGuide, which lists research collections in the Abakanowicz Research Center relating to women, both within the greater Chicago area and within the broader context of the US.