Next week, Chicago welcomes the convening of the Parliament of the World’s Religions at McCormick Place from August 14–18, 2023. CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman writes about the event’s origins and its legacy as the genesis of the interfaith movement.

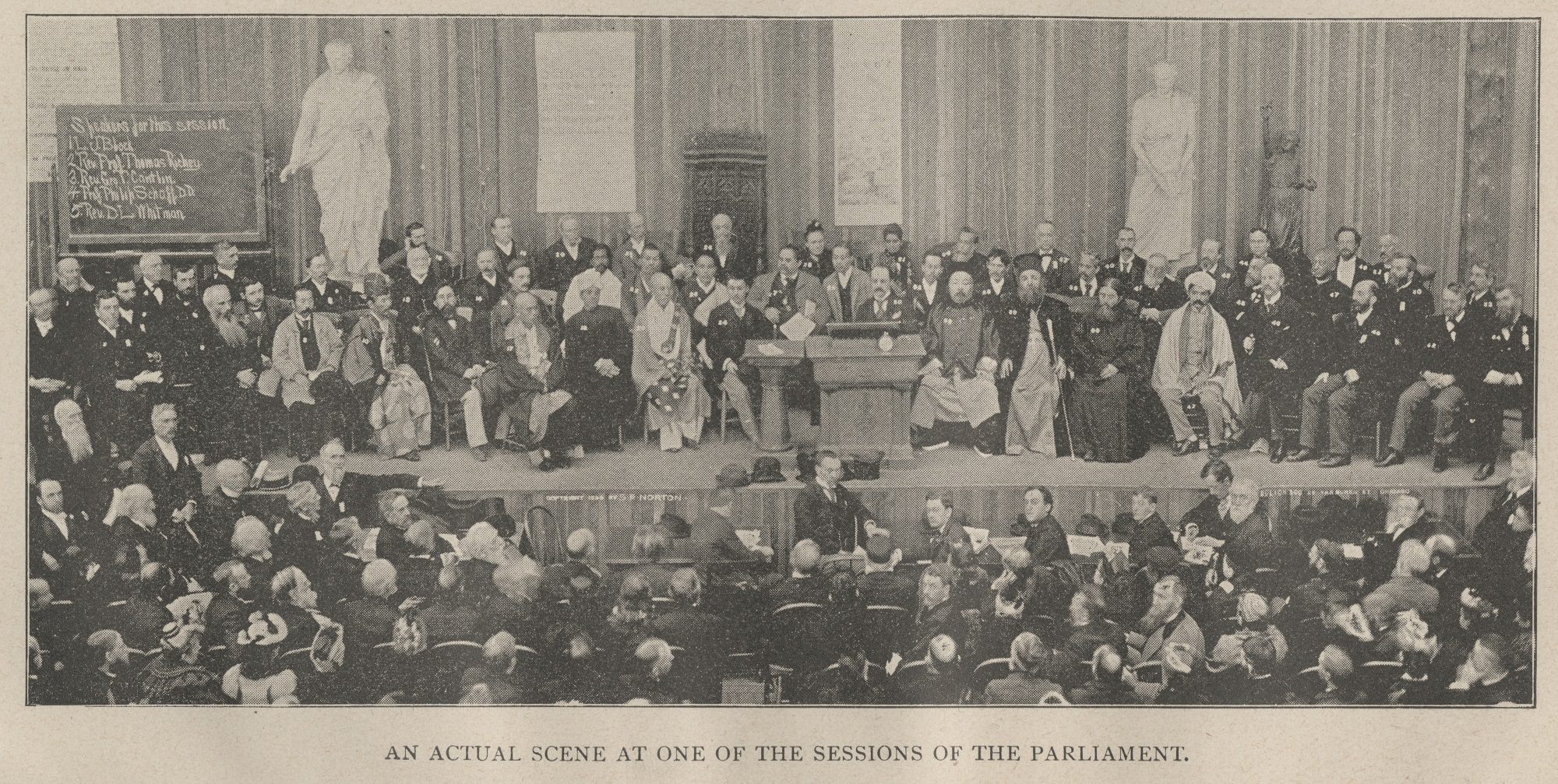

Group photo of scene at one of the sessions of the Parliament from the book The World’s Parliament of Religions, Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-062640

The Parliament of the World’s Religions (PWR) is a legacy of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE). The WCE saw a wide range of national and international representation through its pavilions and attractions. As a complement, the World’s Congress Auxiliary held numerous programs on a wide range of social and cultural topics with the slogan “Not things, but men,” alluding to the congress’s aims to have conversational programs rather than static displays.

Cover page, Neely’s history of the Parliament of religions and religious congresses at the World’s Columbian Exposition / compiled from original manuscripts and stenographic reports. Edited by a corps of able writers. BL21.W8 N4

Throughout the run of the fair, more than 200 individual Congresses were held with nineteen departments represented. Just a sample of the covered topics include women’s progress, commerce and finance, art, government, medicine, and religion. The congresses were organized by Charles C. Bonney, a Chicago judge and author, who, in addition to legal writings, contributed several publications about the world’s fair congresses.

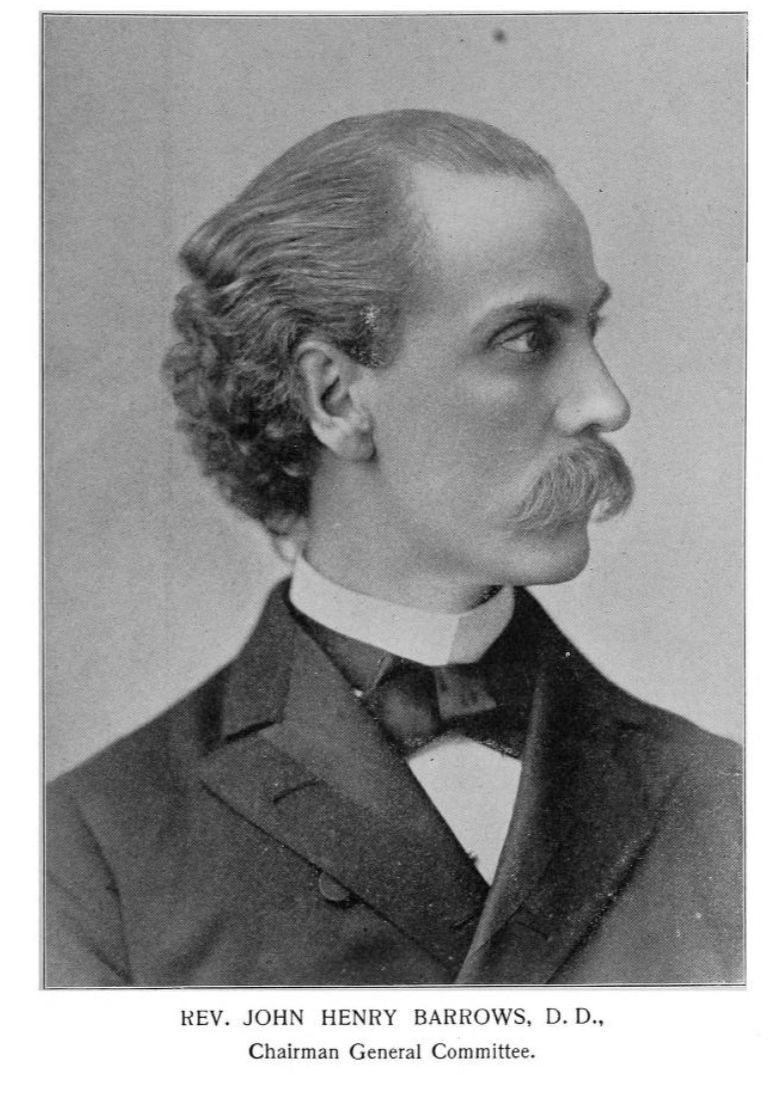

Perhaps the best known today, the Parliament of the World’s Religions was one such congress. Convened from September 11 to 27, 1893, the PWR is regarded today as the origin of the modern interfaith movement. Chicago-based Presbyterian minister Rev. John Henry Barrows served as chairman and, following the Parliament, compiled the event’s proceedings into a two-volume account through his Christian-centered lens.

Portrait of John Henry Barrows from Neely’s history of the Parliament of religions and religious congresses at the World’s Columbian Exposition / compiled from original manuscripts and stenographic reports. Edited by a corps of able writers, p. 18

Invitations to attend were sent globally. While some religious representatives were enthusiastically interested, others were cautiously apprehensive, and some abstained from attending altogether for reasons of belief. For example, the Archbishop of Canterbury declined attending, saying “the difficulties I myself feel are not questions of distance and convenience, but rest on the fact that the Christian religion is the one religion.”

Ten different religions were represented through presenting papers or speeches, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Taoism, Confucianism, Shintoism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Some of the event’s representatives and speakers included Swami Vivekananda (from India representing Hinduism), Anagarika Dharmapala (from Sri Lanka representing Buddhism), Virchand Gandhi (from India representing Jainism), Soyen Shaku (from Japan representing Zen Buddhism), Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb (from New York representing Islam), Henry Jessup (from the US, living in Lebanon, representing Presbyterianism), Pung Quang Yu (from China representing Confucianism), A. G. Bonet-Mary (from France representing Protestantism), Frederick Douglass (from Chicago representing the African Methodist Episcopal Church), Fannie Barrier Williams (from Chicago representing Unitarian Universalism), Antoinette Blackwell (from New York/New Jersey representing Unitarian Universalism), and Emil Hirsch (from Chicago representing Reform Judaism).

The Art Institute of Chicago, designed by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, at South Michigan Avenue and Adams Street, Chicago, 1892. CHM, ICHi-085800

As the PWR opened on the morning of September 11, 1893, a reproduction of the Liberty Bell ran ten times in symbolic honor of the ten traditions present. Representatives marched to the Hall of Columbus in the WCE’s Memorial Art Palace, today home to the Art Institute of Chicago, where a series of welcoming remarks and religious treatises were read.

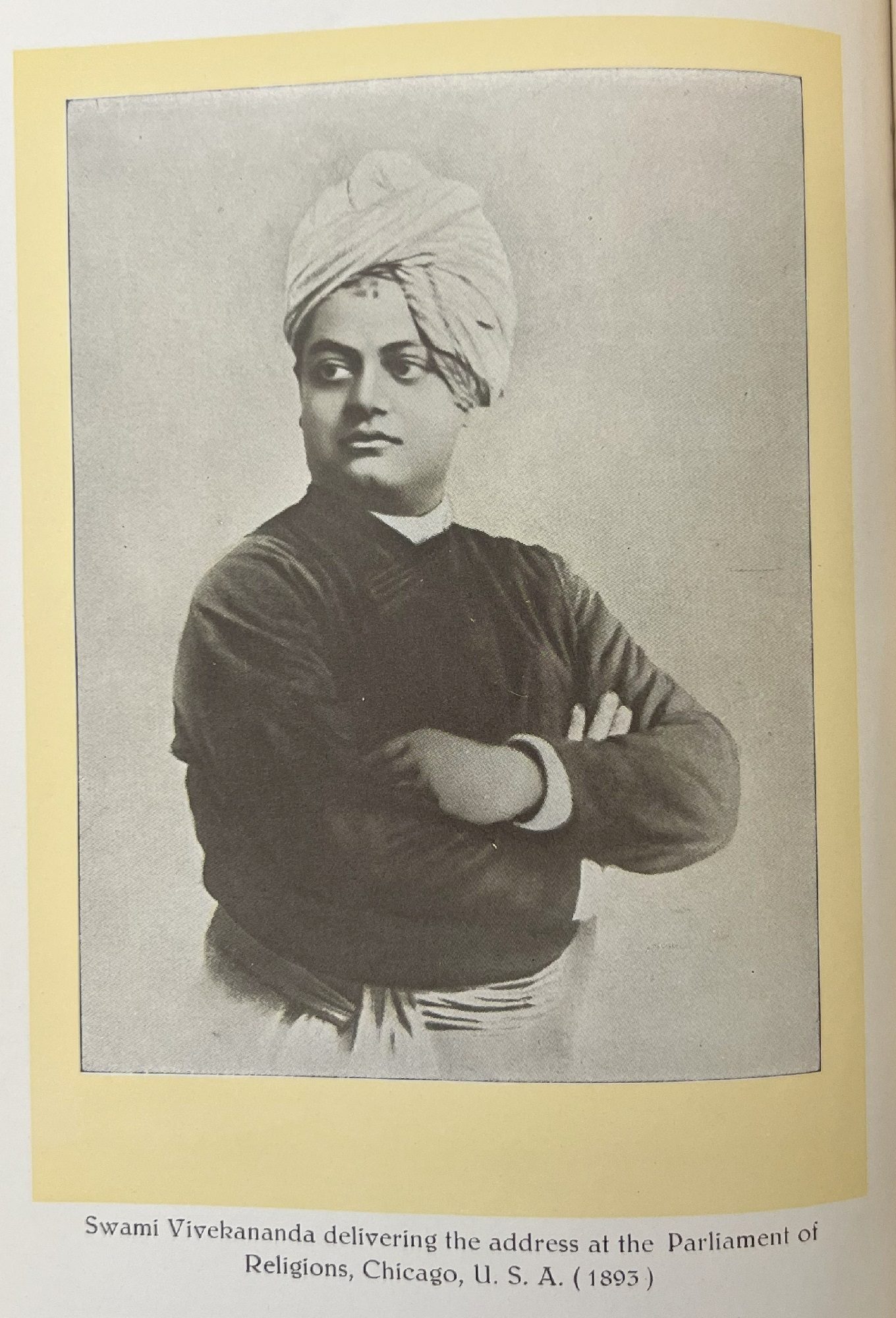

Portrait of Swami Vivekananda from The life of Swami Vivekananda / by his Eastern and Western disciples. X .V68L5 1955

Over the seventeen days of the parliament, speakers from across traditions and nations were given a platform to share about belief and the place of religion through their own lens. Swami Vivekananda (1863‒1902), founder of Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission and the official representative of Hinduism at the PWR, gave an opening speech calling for global tolerance and an end to religious discrimination, saying:

Sectarianism, bigotry, and its horrible descendant, fanaticism, have long possessed this beautiful earth . . . But their time has come; and I fervently hope that the bell that tolled this morning in honor of this convention may be the death-knell of all fanaticism, of all persecutions with the sword or the pen, and of all uncharitable feelings between persons wending their way to the same goal.

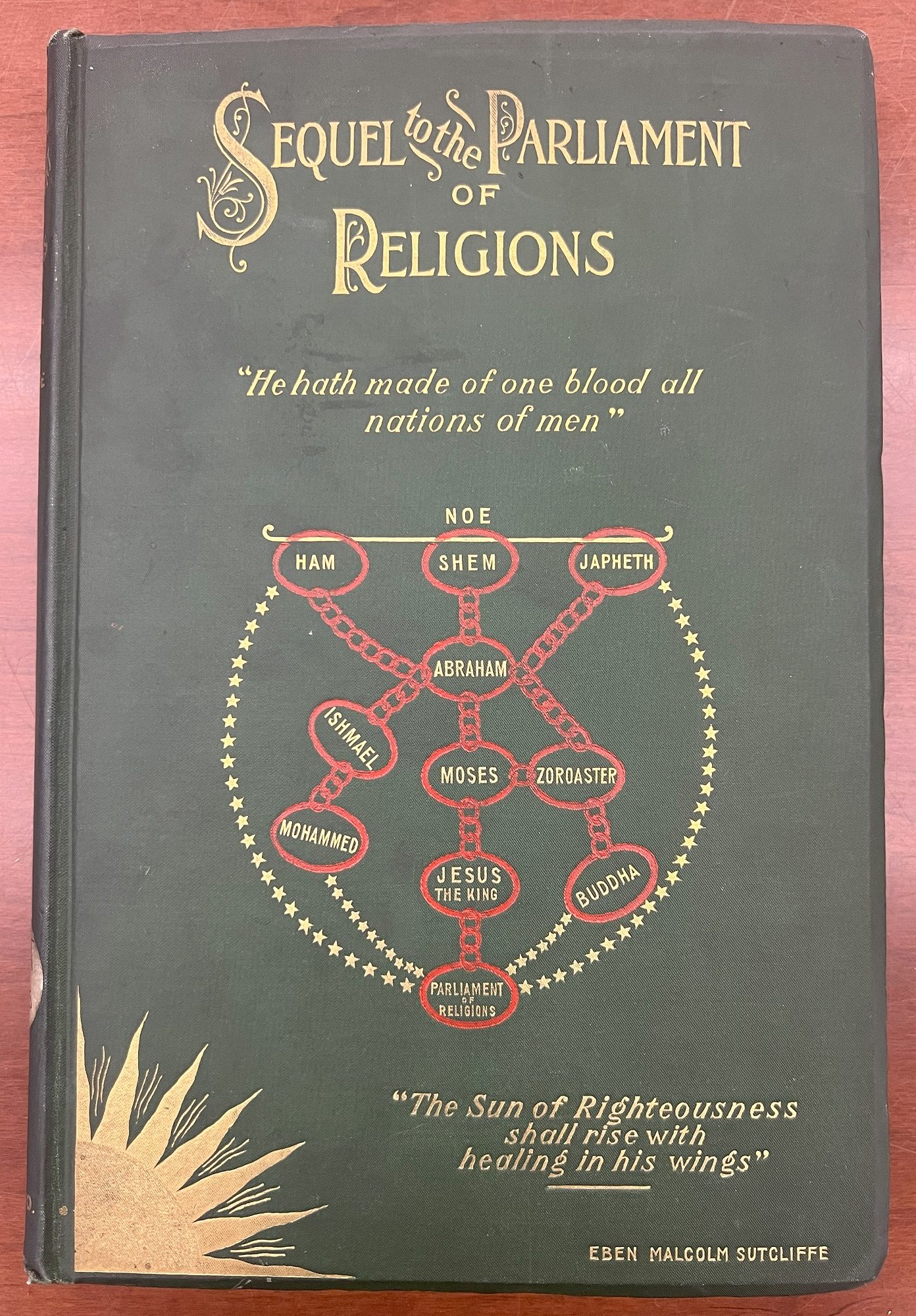

Front cover of Eben Malcolm Sutcliffe, Sequel to the Parliament of Religions, 1894. CHM Collections, F38T .S965

Though proclaimed a universal event, the gathering’s undertones presumed a white Christian religious conviction. For example, the Lord’s Prayer, coming from the New Testament Gospels of Matthew and Luke, was said at each day of the PWR’s convening. Additionally, while seen as socially progressive for its inclusion of non-Western traditions and representatives, there were notable imbalances in non-Christian representation. For example, the underrepresentation of African American Christian leaders, complete exclusion of Native American and Indigenous leadership and perspectives, and purposeful omission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

In the years immediately after the fair, the PWR received much commentary and reflection but later largely fell out of public memory. In the 1970s and 1980s, religious scholarship began questioning why the groundbreaking strides toward religious pluralism present at the 1893 PWR had been mostly neglected in broader pluralist and comparative religious studies. Additionally, critical conversations were had regarding its lack of representation and inclusion, and the claims for its legacy of peaceful universality were questioned.

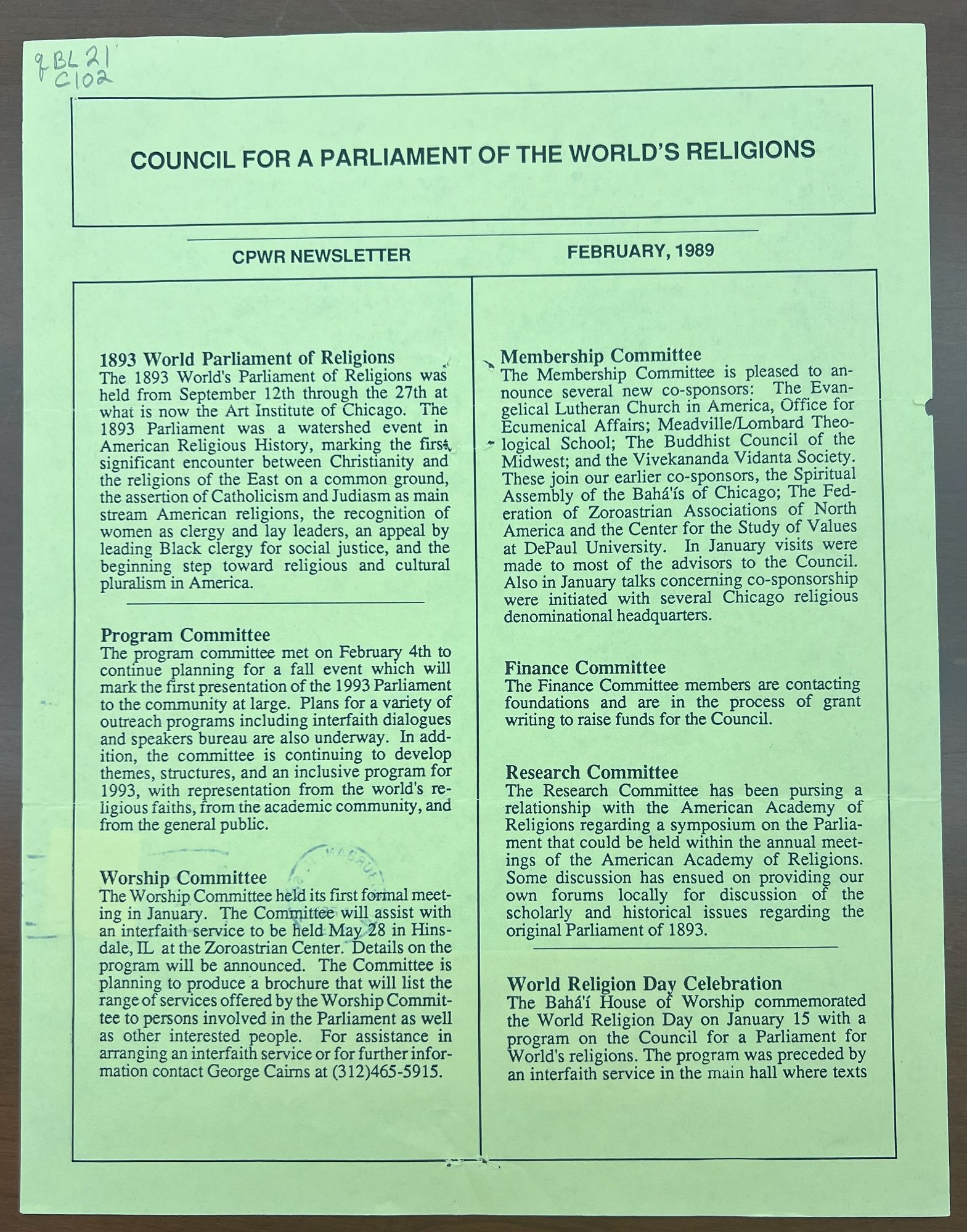

Newsletters published by the Council for a Parliament of the World’s Religions; CHM collections, BL21 .C102 OVERSIZE

In 1988, the Parliament of the World’s Religions was incorporated as an organization with the goal of continuing the legacy of the 1893 gathering through building a platform for interfaith dialogue. This included planning a 1993 convening to mark 100 years since its inauguration. The 1993 Parliament aimed to recontextualize interfaith work in the twentieth century and address the imbalances of the past. This was accompanied by the adoption and publication of The Global Ethic, which proposed a recommended set of shared moral and ethical principles beyond specific religious boundaries.

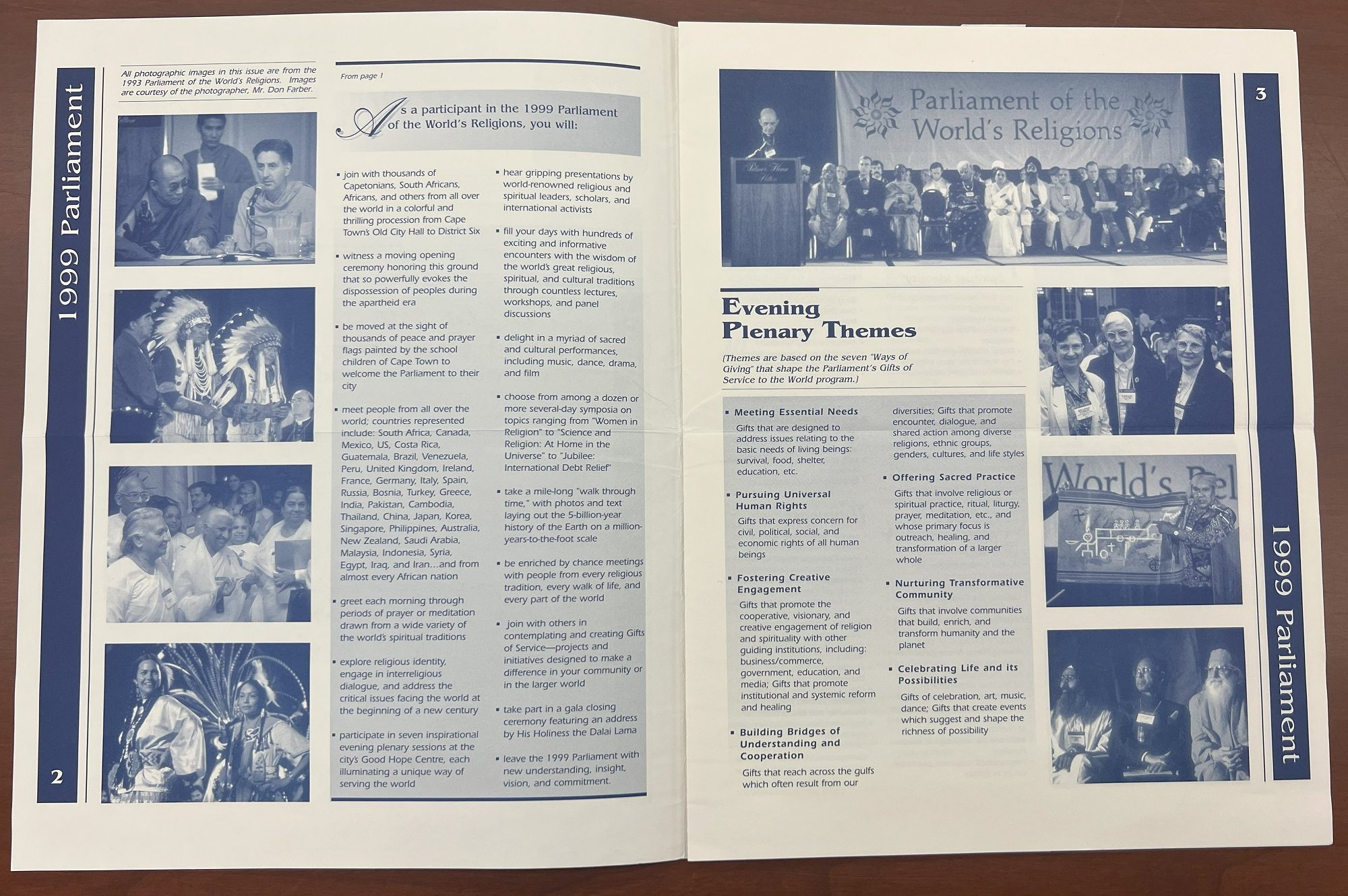

Newsletter describing the program for the 1999 Parliament of the World’s Religions in Cape Town, South Africa, BL21 .C102 OVERSIZE

The Parliament of World Religions has continued to meet in the intervening years, including in Cape Town, South Africa (1999); Barcelona, Spain (2004); Melbourne, Australia (2009); Salt Lake City, Utah (2015); Toronto, Ontario (2018); and virtually (2021). For the first time since 1993, it will return to Chicago in 2023. However, the rich and complex legacy of its first meeting remains present throughout the many communities who have called Chicago home before and beyond 1893.

Additional Resources

- Parliament of the World’s Religions in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Chicago’s influence on religion in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s interviews regarding theology, religion, and religious organizations

- Parliament of the World’s Religions

See what others are saying!