The appearance of pink and white cherry blossoms in Chicago’s Jackson Park marks an end to winter and ushers in a long-awaited spring. In this blog post, CHM curatorial intern Eva Mazzeno talks about the history behind those trees and Chicago’s connections to Japan and Shintō.

Entrance to Garden of the Phoenix and cherry blossoms blooming at Jackson Park, 2023. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman

In Chicago’s Jackson Park, Wooded Island has served as a center of Japanese architecture and culture since the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE). There you can find nearly 190 cherry blossom, or sakura, trees, which the nonprofit Project 120 and the Japanese Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Chicago (JCCC) planted between 2013 to 2016 to mark the 120th anniversary of that world’s fair and the 50th anniversary of JCCC’s founding of in 1966. Each spring, the blossoms invite visitors to engage in hanami, the traditional art of flower viewing.

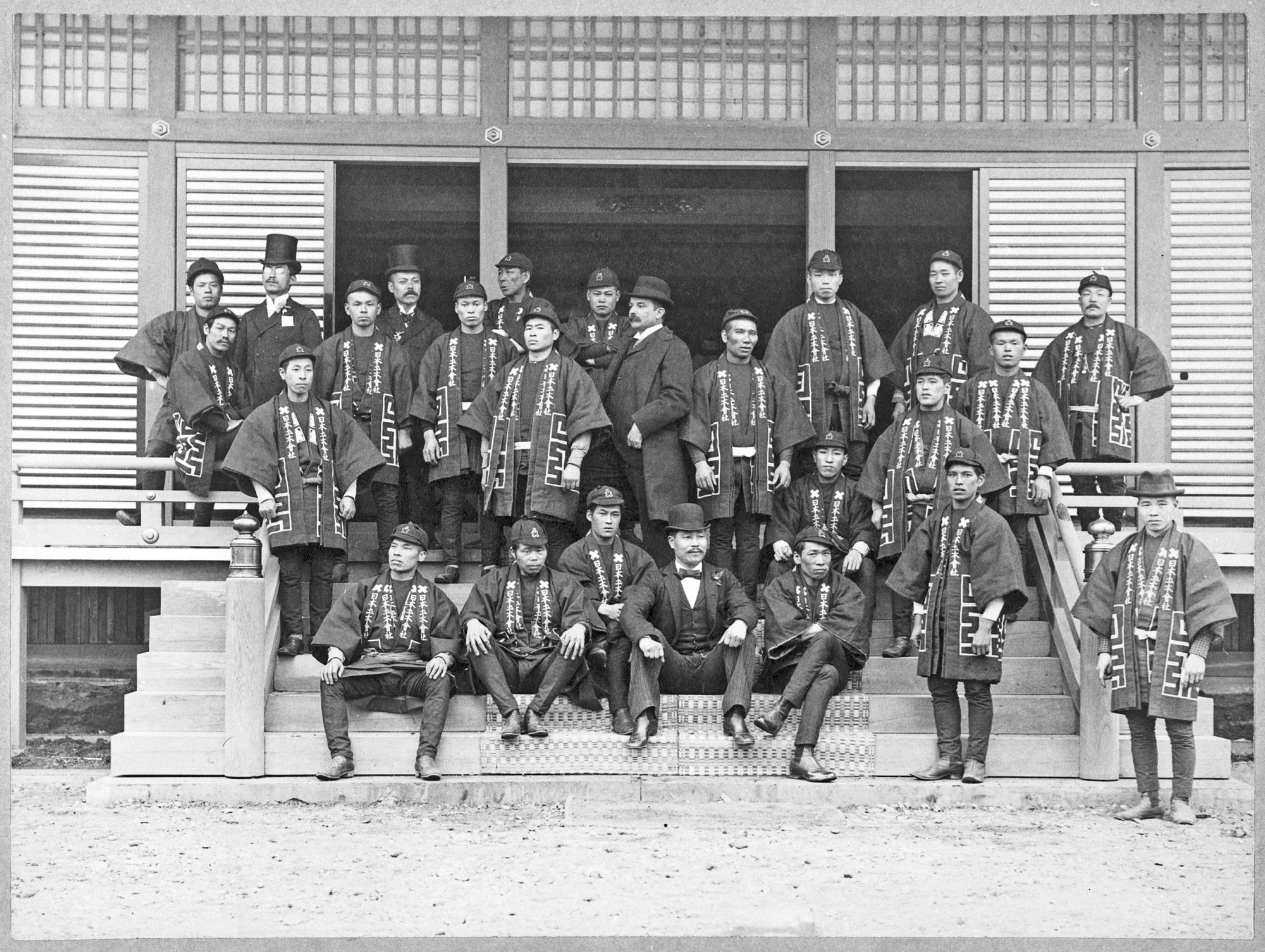

Construction on the Japanese Wooded Island for the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1892. CHM, ICHi-023716

Chicago’s connections with Japan date back to 1893, as Japan was one of the first foreign supporters of the WCE, contributing around $600,000 in total, and the Japanese Pavilion, or Hō-ō-den, was a stunning architectural contribution. Twenty-four highly skilled Japanese carpenters constructed the pavilion using prefabricated materials shipped directly from Japan as a replica of Byōdō-in, a Buddhist temple in Kyōto. The pavilion was gifted to the city of Chicago as a permanent installation—one of only a handful of permanent structures in the fair.

The Japanese Hō-ō-den Temple Complex at the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893. CHM, ICHi-031718; John George M. Glessner, photographer

People at the Japanese Hō-ō-den, World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893. CHM, ICHi-020829

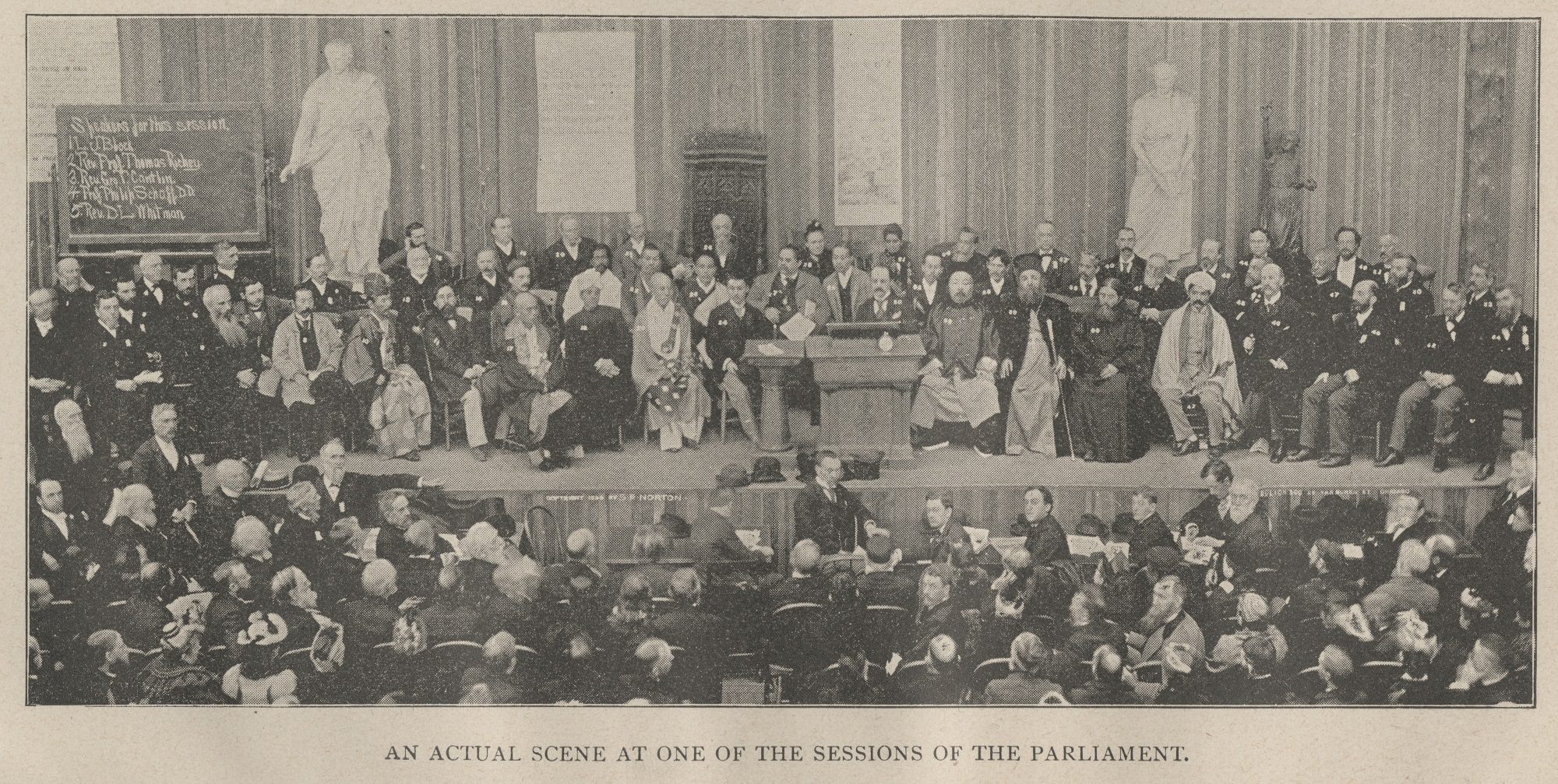

Several Japanese delegates also took part in the Parliament of the World’s Religions, the world’s first interfaith gathering of its kind. While most participating Asian nations sent only one or two members, Japan boasted several delegates representing the nation’s two major religions: Buddhism and Shintō. Varying schools of Buddhism can be found across the globe, but Shintō’s roots are solely within Japan. Shintō is the worship of kami—sometimes translated as “spirits”—which can be found in nature and the “heart-mind” of humans.

“An Actual Scene at One of the Sessions of the Parliament” from The World’s Parliament of Religions: An Illustrated and Popular Story, Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-062640

Buddhism and Shintō had long coexisted in Japan, but two governmental decrees in 1868 and 1871 drastically shifted religious practices by officially separating Buddhism from Shintō. Buddhists were ordered to operate their own temples, and Shintō practices abandoned any usage of Buddhist terminology. As a result, by the time of the 1893 world’s fair, Japanese Buddhists were eager to firmly establish themselves both nationally and internationally and shape global perceptions of Buddhism. All but one of Japan’s delegates to the Parliament were Buddhists, with only Reiichi Shibata to represent Shintō.

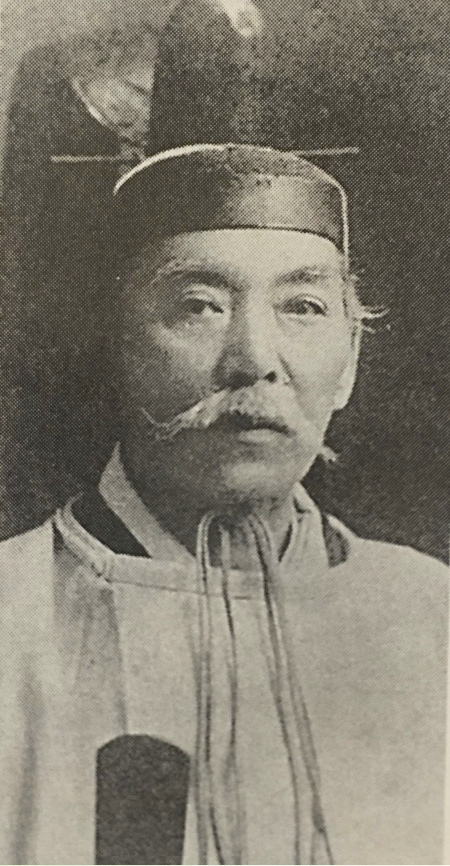

Reiichi Shibata, c. 1900. From Brochure for Jikko-Kyo Shintōism. Courtesy of IMAI Koichi.

Reiichi Shibata (1840–1920) was the second high priest and president of the Jikkōkyō sect of Kyōha Shintō from the Shibata family, inheriting the position in 1890 after the death of his father, Hanamori Shibata. Shibata had been president of the Jikkōkyō sect for just three years by the time of the WCE, taking the reins of one of Shintō’s largest denominations just before its debut on the global stage. Unlike many of the other religions presented at the Parliament, Shintō was almost entirely unfamiliar to American audiences, and it faced sharp scrutiny and racist criticism upon its introduction. Shibata did not engage with accusations, instead choosing to present Shintō in the context of the Parliament’s greater goal “to bring the nations of the Earth into more friendly fellowship, in the hope of securing permanent international peace.”

Upon his return to Japan, Shibata continued to advocate for world peace, especially through the creation of a unified body for international cooperation and the furthering of the growing interfaith movement. He assisted with the founding of the Shintō Dōshikai—now called the Kyōha Shintō Federation—in 1895, an intrafaith coalition of Shintō sects, in which he actively participated until his death. Today, the Shibata family still leads Jikkōkyō Shintō, and Reiichi Shibata is widely credited for his many significant advancements in global Shintō visibility and participation in intra- and interfaith movements.

Sky Landing by Yoko Ono on the original site of Hō-ō-den, 2023. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Wooded Island has undergone significant changes since the WCE. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Hō-ō-den fell into disrepair, and in 1946, it was destroyed completely in an arson attack. In the decades after, however, efforts were made to revitalize the island. Today, Sky Landing (2016), a sculpture by Yoko Ono, Japanese artist and musician, can be found there. Since 1973, Chicago and Ōsaka—Japan’s second largest city—have shared a sister city relationship, opening the door to additional transnational cultural and economic opportunities.

Ginza Holiday, Chicago, c. 1962. CHM, ICHi-111463, Raeburn Flerlage, photographer

Every year, Chicago’s Midwest Buddhist Temple hosts the Ginza Holiday, a celebration of Japanese culture and arts. In the 130 years since Reiichi Shibata’s visit, Chicago’s Japanese American community has thrived, becoming an irreplaceable piece of the city.

Join the Discussion