Latest Posts

We are proud to announce that Hojarasca® Cookies will be available in the Museum’s North & Clark Café, featuring the original recipe created by Francisco and Celia Bonilla, founders of El Nopal Bakery®. In this blog post, CHM historian Jojo Galvan looks back at the legacy of El Nopal and this taste of Chicago history.

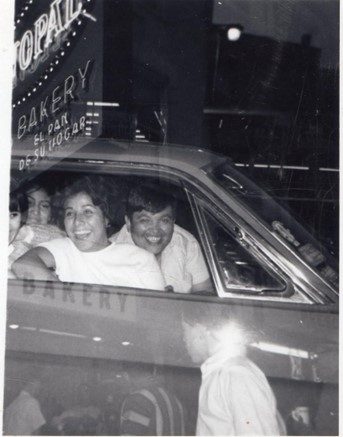

Customers arriving at the 1961 inauguration of the El Nopal Bakery® in Pilsen. The iconic El Nopal® neon sign can be seen reflected in the top left corner of the image. Courtesy of Frank Bonilla

Chicagoans with a sweet tooth likely have a favorite panaderia (Mexican bakery) among the dozens of options on every street across the city’s South and West Sides. The panaderia experience is usually no frills, where visitors can expect a fairly similar setup no matter where they go. Baking trays lined with colorful pieces of pan dulce (sweet bread) fill up the storefront, sometimes behind glass vitrines, other times piled up on baking racks. Self-service is the name of the game. With plastic trays and metal tongs available to shoppers, the selection of goodies isn’t all that different from picking groceries at the supermarket. While some staples, like medialunas/cuernitos (croissants) or mantecadas (sweet buttery muffins) can be found in just about every bakery, the way to stay competitive and develop a dedicated clientele is by offering regional specialties, or, like the legendary El Nopal® bakeries did, offer up original recipes that blend new and old flavors to set you apart from the competition.

The 1961 inauguration of the flagship bakery in Pilsen was blessed by a priest from the nearby St. Francis Church, in University Village. The Bonillas, and their one-year-old son, Frank, are second and third from the left. Courtesy of Frank Bonilla

The El Nopal® bakeries were a twin set of neighborhood bakeries on the city’s Lower West Side that quickly rose in popularity due in no small part to the creation of the Hojarasca® (Spanish for tender leaf) cookie. El Nopal was the dream of husband-and-wife team Francisco and Celia Bonilla, who met in athe bakery where Celia worked in San Antonio. After moving to Chicago, Francisco found work as an artisanal baker in the kitchen of the Palmer House Hotel until they opened their first location on January 1, 1954, at 330 S. Halsted. By 1960, the store moved to its flagship location on 18th Street, and in 1974, a second location opened on 26th Street in the Little Village neighborhood. Through El Nopal®, the Bonillas introduced other products that are now staples in Chicago, the most notable being the Rosca de Reyes (King Cake), traditionally eaten on January 6 to celebrate Epiphany, sometimes called Three Kings Day.

During their more than 60 years of operation, a visit to the El Nopal® bakeries became a rite of passage for anyone traversing through the West Side, from politicians and celebrities to everyday Chicagoans, and a testament to the persistence of the Latine presence across the city. The bakery even makes a cameo in the 1988 action film Above the Law starring Steven Seagal and featured in a number of scenes in the music video for Carlos Santana and Michelle Branch’s 2002 chart topper, “The Game of Love.” The Pilsen location closed its doors in 2013 after the passing of Celia Bonilla, who had been running the business alongside her son, Frank. In 2015, the Little Village location shuttered its doors when Frank decided to retire.

Manuel, who served as the master baker for El Nopal®, visited from Mexico to work with North & Clark Café manager Olga Castrejon on baking according to the traditional recipe.

El Nopal’s best sellers, the heart-shaped Hojarasca® cookies are known by many names (Biscochitos, Mexican Shortbread Cookies, Wedding Cookies, etc.), but the recipe created by the Bonillas is one of a kind. Crafted from a highly guarded blend of specific flour, spices, and baking techniques, the recipe was, for years, known only to the Bonilla family and El Nopal®’s master baker, Manuel, who resides in Mexico. However, as part of the larger Aquí en Chicago project, and thanks to a partnership between Frank Bonilla and CHM’s North & Clark Café, the Museum is thrilled that El Nopal®’s Hojarasca® cookies will once again be available for purchase, with batches made daily in the Museum café following the same recipe that made the Bonillas legends amongst Chicago’s panaderos.

Available daily while supplies last.

A fresh batch of Hojarasca® made at the North & Clark Café.

This blog post would not have been possible without the research of Deborah Kanter, author of Chicago Católico: Making Catholic Parishes Mexican, available at CHM’s Museum Store and online.

From the early 1970s to 1989, St. Sebastian Catholic Church in Chicago was a home for Catholic members of the LBGTQIA+ community. CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman talks briefly about the church’s history, its place in the city’s LGBTQIA+ history, and the broader history of the Roman Catholic Church’s relationship with the LGBTQIA+ community.

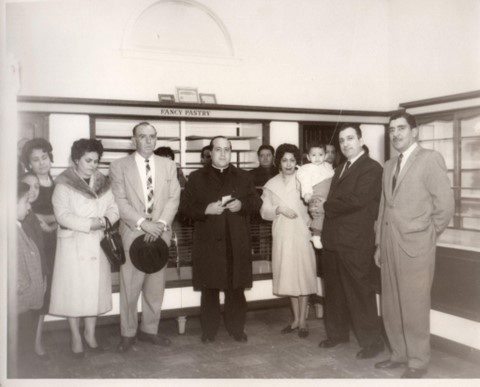

Images from the 20th Annual Pride Parade on Broadway Avenue in the Northalsted neighborhood, 1989, from CHM, Lee A. Newell II Visual Materials, 1997.0093, box 3.

For decades, Pride in Chicago has been affiliated with the North Side neighborhood of Northalsted, formerly known as Boystown, in the Lake View community area. The city’s first Pride parade was held in June 1970, one year after the Stonewall Uprising, and has become a principal annual recognition of LGBTQIA+ history and presence in Chicago. Parades also served as protest, asserting visibility and claiming the right to take up space in the public sphere.

Stonewall marker on the Legacy Walk on North Halsted Avenue in the Lakeview community area. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman, 2022.

As Northalsted has continued to grow in its global recognition as an LGBTQIA+ inclusive neighborhood, so too has the commemoration of LGBTQIA+ histories. For example, the Legacy Walk on North Halsted Street, running between Belmont Avenue and Grace Street, is an outdoor museum consisting of a series of ten steel monuments memorializing biographical histories and legacies of LGBTQIA+ individuals around the world. Inaugurated in 2012, it was initially inspired through the Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt in 1987. Each steel monument holds four bronze plaques, making 40 total, with new figures added annually. These monuments have made, and continue to make, LGBTQIA+ histories public that may otherwise be lesser known, hidden, or forgotten.

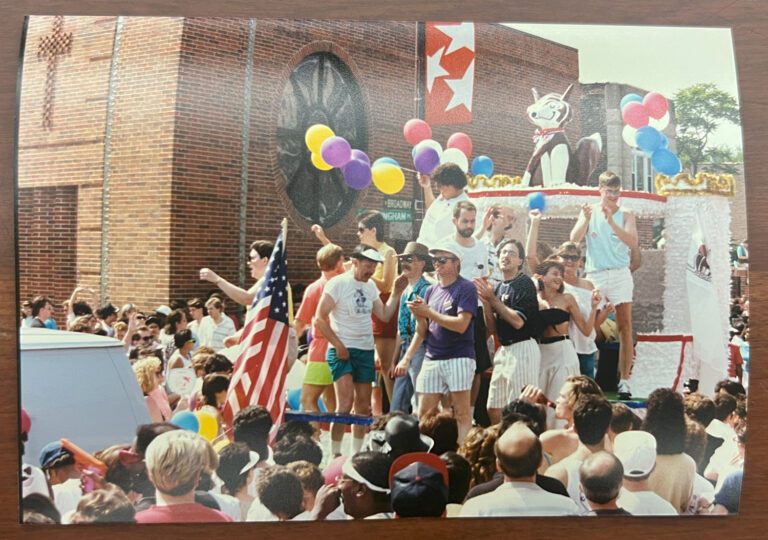

Interior view of St. Sebastian Church, August 31, 1953. Photograph by Hedrich-Blessing, CHM, HB-16434A

While more people may be familiar with these community markers and public displays, LGBTQIA+ history in Chicago is found in many lesser-known places around the city that do not have the same public memorialization. St. Sebastian Catholic Church is a story of one such lesser-known history.

View of St. Sebastian Church being moved down West Wellington Avenue in the Lakeview community area of Chicago. March 15, 1915. DN-0064260, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, CHM.

The home of St. Sebastian Catholic Church was built as a simple wooden structure in 1886 on the corner of Wellington Avenue and Bucher Street (now Wilton Avenue), initially housing the congregation of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. In 1912, the congregation divided, and those who stayed at Wellington and Bucher became known as St. Sebastian’s, with Our Lady of Mount Carmel moving to a new chapel at Belmont Avenue and Clark Street. The physical structure of St. Sebastian’s was moved a couple of years later to the corner of Wellington Avenue and Dayton Street.

Over the next decades, St. Sebastian Catholic Church became known for serving a diverse body of worshippers, welcoming Polish, South American, Asian, and Puerto Rican churchgoers and holding a weekly Spanish mass. From the early 1970s to 1989, the church was an important place for the LGBTQIA+ community as the home to a weekly welcoming and affirming mass.

Dignity/Chicago newsletters, November 1977 and August 1980.

At this time, affirming masses at St. Sebastian’s were held on Sunday evenings and stewarded by an independent organization known as Dignity/Chicago. Formed in January 1972, Dignity/Chicago is a local chapter of DignityUSA, a national organization whose mission is “to work for respect and justice for all gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender persons in the Catholic Church and the world.” It was founded to serve as a support for LGBTQIA+ Catholics, so they are “affirmed and experience dignity through the integration of their spirituality with their sexuality, and, as beloved persons of God, participate fully in all aspects of life within the Church and Society.” By the 1980s, the national organization had 110 chapters nationwide, and the local Chicago chapter grew to over 150 members.

Religious service held in Lincoln Park as part of Pride week, June 22, 1977. ST-17300370-0009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Despite this growing acceptance and presence in the Catholic church locally, the global church’s stance remained firmly positioned against full LGBTQIA+ inclusion. In 1986, the Vatican published a document titled On the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons, which sought to clarify the global Catholic Church’s position. While the directive claimed to affirm dignity for all people and permitted pastoral care to LGBTQIA+ people, it explicitly called homosexuality an “intrinsic moral evil,” instructing bishops to pull their support from organizations that contradicted the church’s official stance, including their use of Church buildings and facilities.

For some time following the edict’s pronouncement, Cardinal Joseph Bernardin permitted St. Sebastian’s priests to continue leading mass with Dignity. However, in May 1988 it was announced that services would be taken over by the archdiocese, with services led by pastors from five other churches who would lead “in accord with church teaching and discipline.” This approach had divisive results, with some saying they felt more supported by the Catholic church under diocesan leadership while others felt unwelcome.

Broadway United Methodist Church in the Northalsted neighborhood. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman, 2022.

In May 1988, a majority of Dignity members voted to move their services to a non-Catholic facility and in June began worshipping at nearby Resurrection Lutheran Church. They would hold mass in several welcoming Protestant churches before finding a new permanent home at Broadway United Methodist Church in 1992.

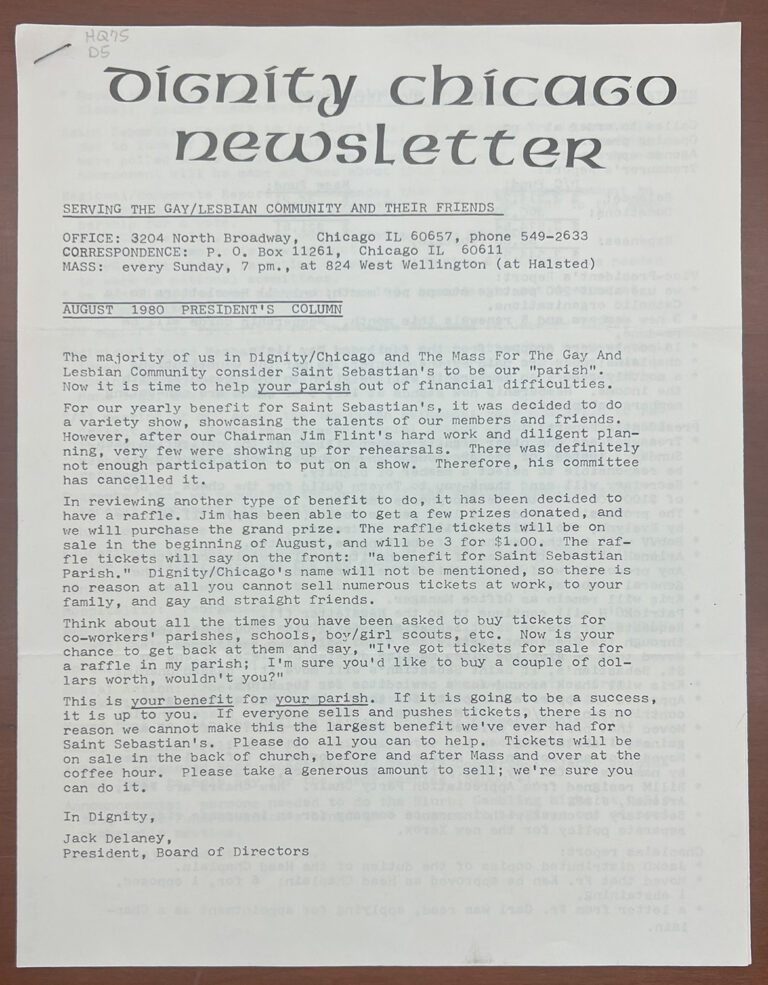

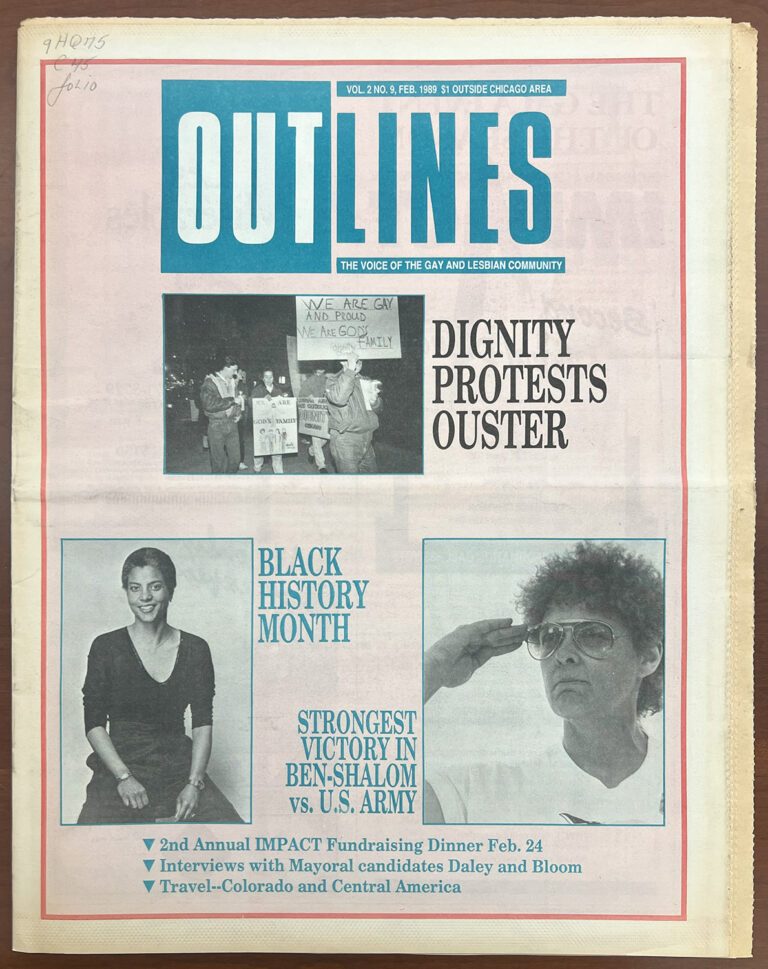

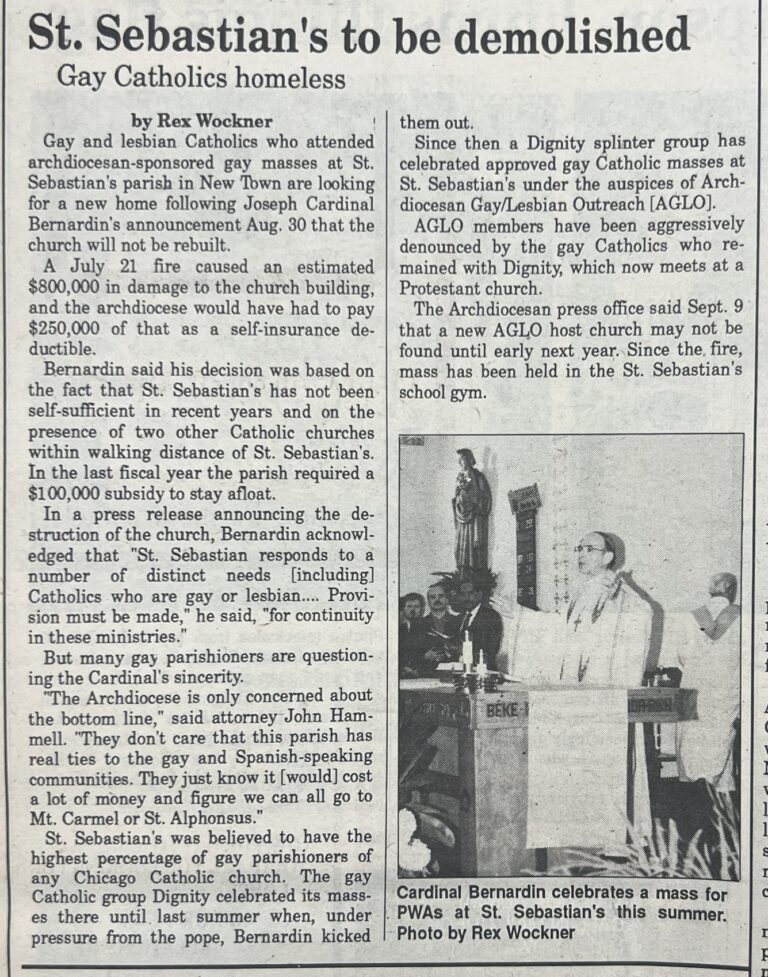

Outlines cover and detail from p. 16, February 1989. CHM, Outlines, HQ75.C45 Folio.

For LGBTQIA+ parishioners who chose to stay at St. Sebastian’s, through discussion with Cardinal Bernardin and LGBTQIA+ leaders, the affirming Sunday evening mass began to be led by the Archdiocesan Gay and Lesbian Outreach (AGLO), a ministry of the Catholic Church. However, by this time general attendance across all services at St. Sebastian’s—three English speaking, one Spanish speaking, and AGLO’s mass—was declining and financial challenges were growing. These issues compounded exponentially when a basement fire broke out in July 1989, creating hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of damage, essentially hollowing out the church building completely. The fire ultimately became the final straw in the congregation’s vitality and in December, Cardinal Bernardin announced St. Sebastian’s would not be rebuilt, closing officially on June 30, 1990.

Sanctuary of Mount Carmel Catholic Church, Photograph by Rebekah Coffman, 2022.

Following St. Sebastian’s closure, surviving relics, church staff, and some parishioners moved to nearby Our Lady of Mount Carmel parish, which continues today as the “mother church” of AGLO. In a July 24, 1989, Chicago Tribune article titled “Parishioners keep faith after fire,” Juan Mosquera, a Cuban migrant who came to Chicago in 1962, is quoted saying, “The real church, the people—English, Spanish, gay—we are still here. We party together, we cry together.” Today, the global Roman Catholic Church still does not fully doctrinally affirm LGBTQIA+ people and lifestyles. However, recent shifts, such as Pope Francis’s authorization of blessing same-sex couples in December 2023, are evidence of the continuing legacy of decades of strives for full inclusion.

Additional Resources

- Listen to Studs Terkel interviews with LGBTQIA+ activists, artists, and writers between the early 1960s and the early 1980s

- View our 2D materials relating to LGBTQIA+ peoples and history at the Abakanowicz Research Center

- Use our LibGuide to aid in your research relating to LGBTQIA+ peoples and history

- Visit the LGBTQ Religious Archives Network

In this blog post, CHM curatorial fellow Elizabeth Barahona recounts the police violence against Republic Steel organizers in what came to be known at the “Memorial Day Massacre” with a focus on the harm done to two Latino workers.

Content warning: This post contains images of violence and police brutality.

On Memorial Day, Sunday, May 30, 1937, several hundred individuals—white, Black, and Latino men, women, and children—were peacefully protesting at Republic Steel on Chicago’s far Southeast Side. The demonstrators presented the steel company with demands that included recognizing their union, ratifying a labor agreement, raising wages, enhancing workplace safety, and ceasing unfair labor practices such as suppressing and retaliating against union activities.

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 had guaranteed workers the right to organize into trade unions, engage in collective bargaining, and participate in collective actions like strikes. So, the protesters approached the Republic Steel plant with hope. After all, just a few months earlier, in March 1937, U. S. Steel, the country’s largest steel producer, had agreed to a union arrangement, setting a precedent for others like Republic Steel to emulate.

Families began the day at the union headquarters, a quaint establishment known as Sam’s Place. Dressed in their Sunday best—suits, white dress shirts, dark pants, complemented with a variety of fedora, panama, homburg, and poorboy hats—they planned a parade at the conclusion of the protest march. Unfortunately, the day did not go as planned.

Republic Steel had anticipated their demonstration and acquired more than $50,000 worth of tear gas to supply the Chicago police merely ten days prior. They also procured distinct white clubs fashioned from hatchet handles—vastly different from the standard police nightsticks. The Chicago police intentionally increased their force to 264 officers that afternoon.

Police confronting strikers outside Republic Steel during what became known as the Memorial Day Massacre; some police can be seen holding white hatchet handles, Chicago, May 30, 1937. DN-C-8769A, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

As the protesters marched, they faced a formation of uniformed police officers. What followed was a harrowing display of state force: police threw tear gas canisters, fired bullets, and used their clubs to brutally bash the heads and bodies of the demonstrators.

The aftermath of the violence was catastrophic: ten lay dead, 40 were shot, and more than 90 were wounded.

Among the injured was Ms. Guadalupe “Lupe” Gallardo Marshall, a petite 31-year-old Mexican immigrant and volunteer social worker at the Hull-House Settlement. Marshall stood among the 200 women at the march. Police officers beat her, but even as she tried to escape, she defended her unconscious fellow protestors. Police forced her into a packed wagon, alongside other injured demonstrators, where despite her own injuries, Marshall attended to other victims. The wagon deliberately roamed the city, delaying its arrival at Burnside Hospital on the South Side.

Lupe Marshall can be seen in this photograph of picketers rushing to Republic Steel strikers on the ground, May 30, 1937. Courtesy of the Southeast Chicago History Society, Archive ID: 1981-077-079k, gift of Edward Sadlowski.

At the South Chicago Police Station, the police detained other injured protestors for up to three days. One of those detained was Max Guzmán, a 26-year-old Mexican steelworker, who had been struck in the head by an officer. Without providing medical care, police fingerprinted Guzmán at the station, interrogated him about alleged communist ties, and when they learned he was not a US citizen, threatened him with deportation.

When the dust settled, influential newspapers such as the New York Times and the Chicago Daily Tribune, owned by the staunchly antilabor and McCarthyist McCormick family, presented an inaccurate narrative, accusing the protesters of everything from initiating the violence on police, to being under the influence of drugs and subscribing to communist ideologies.

Fortunately, journalists and cameramen from other media outlets, including Paramount News, attended that day. Paramount executives initially withheld the footage they captured, fearing that its release to the public might cause significant unrest or backlash, but it was ultimately released during a monumental US Senate investigation into the event.

Another Chicago Daily News image of police confronting strikers, Chicago, May 30, 1937. DN-C-8769B, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

From the footage, the Senate committee determined that the police made many baseless allegations, including lying about carrying regulation equipment-night sticks and instead carrying hatchet-handle clubs and tear gas. The investigation exposed the truth and debunked other police claims, revealing their aggressive, unprovoked tactics and the subsequent cover-up. The Senate concluded that the police did not properly prepare their officers with clear instructions, used excessive force in their interactions with protestors, and did not carry out an honest investigation of the events.

As the newsreel footage played across cinemas nationwide, the truth of the “Memorial Day Massacre” became undeniable. This event, the victims, the survivors, and the media’s role in shaping its narrative underscore the everlasting importance of documenting and challenging power. And the resilience and sacrifices of Latinos such as Lupe Marshall and Max Guzmán, especially in the face of police brutality, underscore the pivotal role they played in the struggle for justice and equity in Chicago.

Women protesters picketing at City Hall in support of Republic Steel strikers after what is known as the Memorial Day Massacre, Chicago, June 2, 1937. DN-C-8805, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Additional Resources

- See the Southesast Chicago Historical Society’s Memorial Day Massacre story

- Listen to Dr. Lewis Andreas talk to Studs Terkel about being at the Memorial Day Massacre

- See the PBS documentary Memorial Day Massacre: Workers Die, Film Buried (2023)

As part of our Chicago Metro History Day program, Josue Contreras, a history teacher at H.B. Stowe Dual Language School, worked with Joshua Mendez, a student at Wheaton North High School, to research and produce a Silent Hero® profile as part of Sacrifice for Freedom®: World War II in the Pacific Student & Teacher Institute, a National History Day® program.

You know why people love war series like Band of Brothers? It’s not the action or the history of it all (though that doesn’t hurt), but rather the stories of the real-life heroes portrayed in these shows. We are awestruck by how ordinary people rose to the extraordinary challenges of their time to seemingly become Marvel superheroes in their own right, and we ask questions like “Why didn’t I learn about this in school?” Well, it’s the mission of the National History Day to answer those questions through their Sacrifice for Freedom®: World War II in the Pacific Student & Teacher Institute.

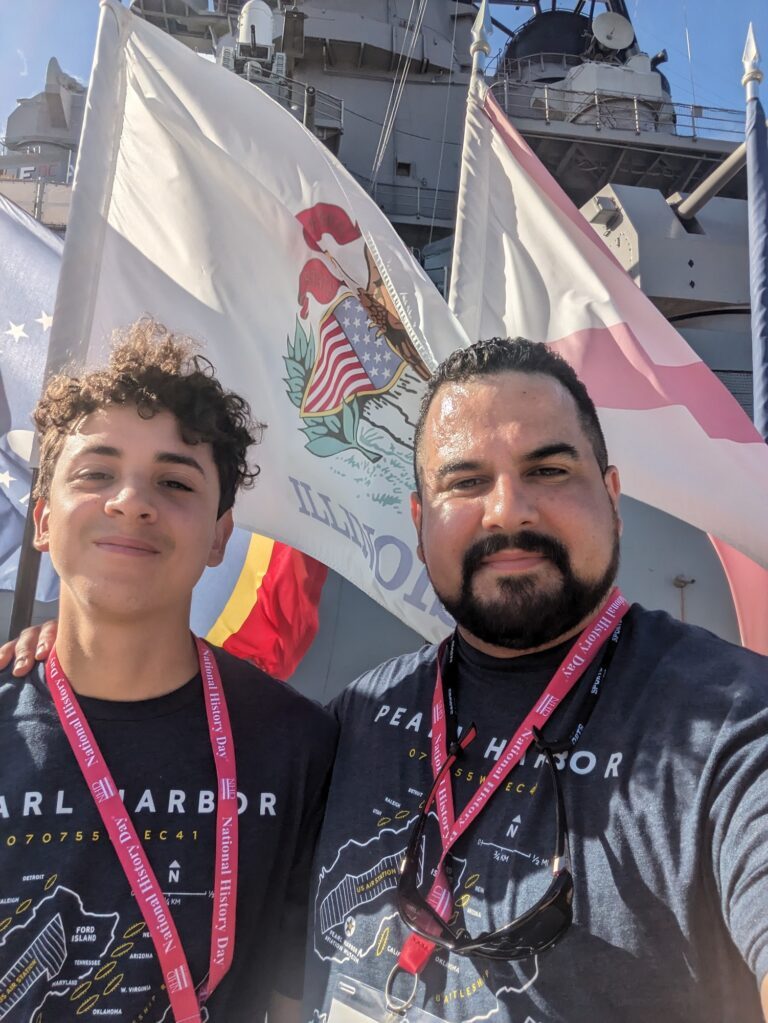

Joshua Mendez (left) and Josue Contreras (right) at the USS Missouri, Pearl Harbor, Honolulu, Hawai‘i, 2023. Photograph by Josue Contreras

Each year, National History Day takes 16 teacher-student teams from across the country through a six-month genealogical research project where each team chooses a World War II serviceman or woman to research their life, service, and sacrifice and ultimately share their extraordinary accomplishments with the world. The project culminates in a week-long stay at Pearl Harbor with each team reading a eulogy for their chosen hero at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific.

Joshua Mendez (right) and Josue Contreras (left) reading PFC Felipe Sanchez’s eulogy at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, Honolulu, Hawai‘i, June 25, 2023. Photograph by Westin Saito, Education and Interpretation Research Coordinator at Pacific Historic Parks

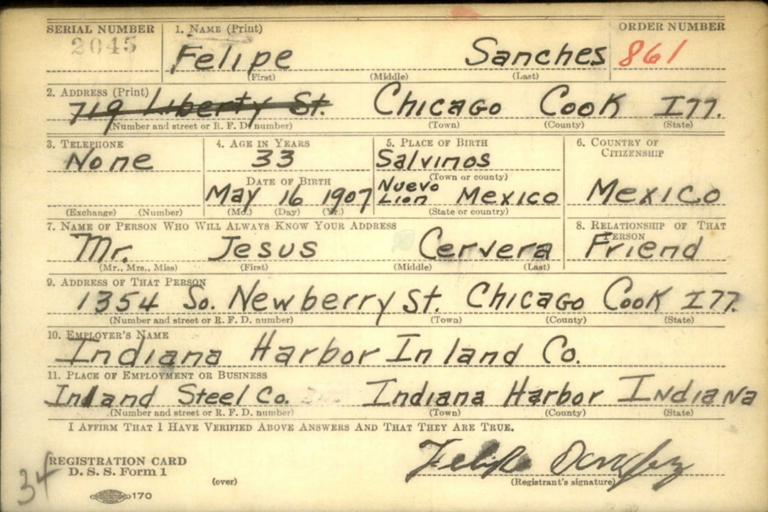

Representing Team Illinois, Joshua and I really wanted our unsung hero to represent the Latino experience during the war―a perspective that we felt had been lacking in the general retelling of WWII history. We landed on Private First Class Felipe Sanchez (1907–45) and little did we know how inspiring his story would be. At the start, all we had to go on was his draft card. During the next six months, we would pull at every little thread we could find to piece together the life of a Mexican national who immigrated to the United States by uncertain means and happened to be living in Chicago and working at an Indiana steel mill on the national draft day in 1941.

Ancestry.com. US, World War II Draft Cards Young Men, 1940–47 [online database]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

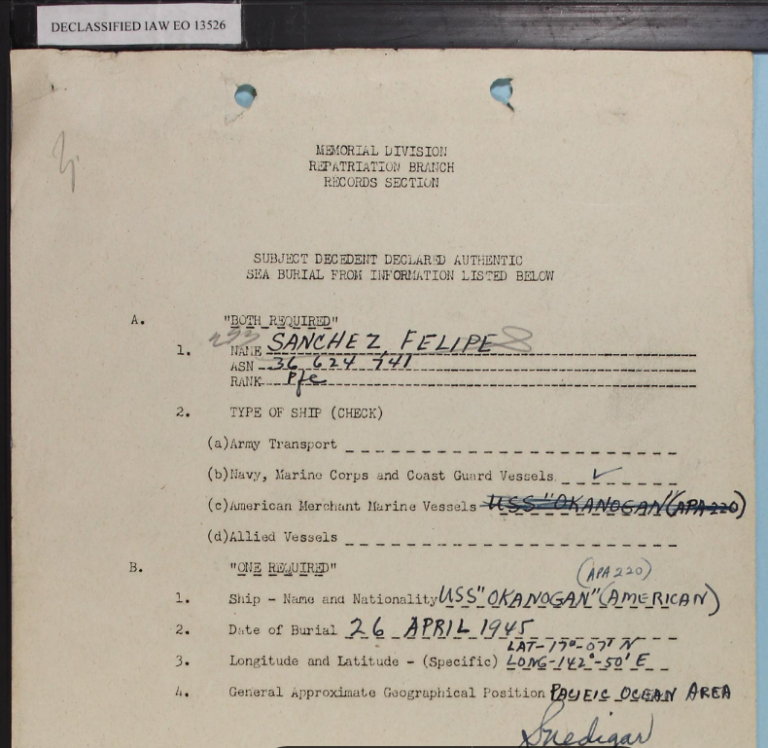

The program taught us historical and genealogical research skills that aided us in reconstructing PFC Sanchez’s life 80 years after his passing. It required days in Chicago-area museums and library archives, multiple requests for records, reading dozens of WWII-era books, and learning how to interpret historical documents to make educated assumptions about PFC Sanchez’s life before and during his service, as well as the circumstances of his death. In the end, we put together the best retelling of his life, service, and sacrifice we could given that: we were never ever able to find any next-of-kin, his official Army personnel file was burnt in the 1973 National Personnel Records Center fire, and any documentation from his early life by the Mexican government archives had not yet been digitized.

Army deceased personnel file of PFC Felipe Sanchez – National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis, Missouri

All in all, the time we spent uncovering PFC Sanchez’s story was worth it. We now have a greater appreciation of the sacrifices of “The Greatest Generation” and the contributions of Latinos during the war, as well as increased understanding of the hard work film studios and historians undertake to reconstruct the stories they tell in their war dramas. Stories of heroes once thought lost to history, but no more.

Joshua Mendez (left) and Josue Contreras (right) at PFC Felipe Sanchez’s memorial at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, Honolulu, Hawai‘i, June 25, 2023. Photograph by Westin Saito, Education and Interpretation Research Coordinator at Pacific Historic Parks

Additional Resources

- Read the Silent Hero® profile on PFC Felipe Sanchez

- Learn how you can take part in Chicago Metro History Day as a student, educator, or volunteer judge

- Visit CHM’s Abakanowicz Research Center to help with your genealogical research

- See more of CHM’s ongoing research on Latine communities in Chicago as part of Aquí en Chicago

You’ve probably heard the phrase “say it with flowers,” but how specific can you get with what you say? The “language of the flowers” was first formalized in the early 19th century and went on to achieve widespread imitation and mutation over the course of the next two centuries.

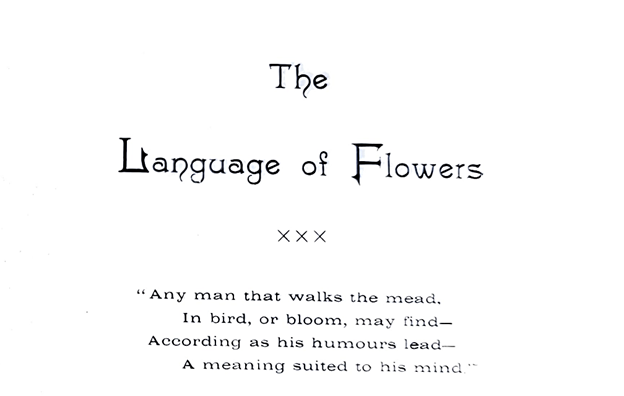

Excerpt from The Language of Flowers by A. Lange (Chicago: S.D. Childs)

Though there is scant historical evidence it was ever used by couples as a practical “language” to communicate precise messages, such as “Meet me this evening in the town square,” the romance of that idea captured the public’s imagination. Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, there was a huge demand for published “floral dictionaries” promising to help decode messages hidden in bouquets. In these guidebooks, each flower is assigned a specific sentiment and thus by composing a floral arrangement, one might hypothetically convey complex thoughts and messages to the intended recipient.

Pauline H. Solomon holding a bouquet of flowers, standing in a dining room in Chicago, 1915. DN-0064300, Chicago Daily News Collection, CHM

The main obstacle to the language of the flowers becoming universal was the fact that there were no agreed upon meanings for every flower. The meanings were often arbitrarily pulled from poetry or the medicinal uses for certain plants, so while one dictionary might list the white rose’s meaning as “I am worthy of you” another might say it stood for “silence.” Florists in particular profited off selling the romance of the language of the flowers to their customers and continued making and selling floral dictionaries long after mainstream publishing interest in the genre declined in the 20th century.

Wedding bouquet, dried flowers, no date. CHM, ICHi-054714

One Chicago florist who published such a dictionary was August Lange, who worked in the floral industry from age 13 until he passed away at age 73 in 1942. His shop near the Palmer House was a Loop staple for 55 years, where he brought the practice of importing orchids from Canada to Chicago (Chicago Daily Tribune, March 29, 1942, p. 18). As was common with floral dictionaries, Lange’s The Language of Flowers includes poetry about flowers, as well as an index of flowers and their associated meanings.

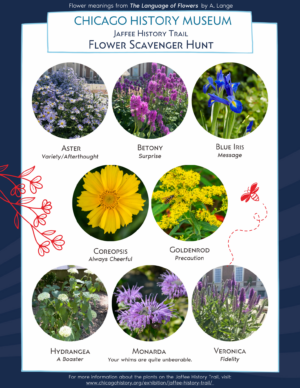

Chicago’s official city motto is urbs in horto or “city in a garden,” and the Richard M. and Shirley H. Jaffee History Trail at the Chicago History Museum is one of the many gardens that helps the city fulfill that motto. See which ones you can spot and decode their historical sentiments using the guide below!

Download Jaffee History Trail Flower Scavenger Hunt Here

Further Reading

- Read The Language of Flowers by A. Lange here.

- See what native flora appear on the Jaffee History Trail.

- Beverly Seaton, The Language of Flowers: A History (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012).

- “August Lange, Florist in Loop 55 Years, Dies: Funeral Rites to be Held Tomorrow Afternoon.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1923–1963), March 29, 1942, p. 18. Accessed March 14, 2024.

- George Neville Jones, Flora of Illinois: Containing keys for identification of flowering plants and ferns, 3rd (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1963).

While conducting research in the Abakanowicz Research Center, CHM communications intern Lucia Wang found negatives documenting Chinese hand laundry shops in Chicago. In this blog post, she shares a brief history of Chinese laundries in Chicago within the larger context of Chinese immigration to the United States.

“In another life, I would have really liked just doing laundry and taxes with you.”

As this line went viral and Michelle Yeoh made history as the first Asian woman to win Best Actress at the Academy Awards, the film Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022) has reshaped the way Chinese laundry workers are depicted onscreen, introducing an alternative positive perspective. Why do Chinese Americans in films or tv shows always seem to run laundries? Why are soap and irons often associated with them and suggest a negative connotation?

The story can be traced back to the mid-nineteenth century California Gold Rush, during which numerous Chinese people immigrated to the United States. However, many of them were forced to work in laundries due to many reasons, including their limited proficiency in English. In 1851, Wah Lee opened the first Chinese laundry in San Francisco, which sparked an explosive growth in similar stores. (1) White workers often perceived Chinese laborers as a threat to their own employment, due to the low wages and long working hours Chinese laborers performed. The hostility reached its peak with the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which put a 10-year ban on Chinese laborers from immigrating to the United States. The stigmatized depiction of Chinese laundries and workers continues to appear on posters, trading cards, and magazine illustrations, even current popular culture.

A streetscape showing businesses on the 1600 block of West Madison Street including Sing Wah Hand Laundry (right), Chicago, c. 1910. CHM, ICHi-067272; Charles E. Barker, photographer

The expansion of Chinese laundries extended to the Midwest, with the first Chicago store opening in 1872 at 167 West Madison Street (now 158 West Madison Street). (2) In Paul C. P. Siu and John Kuo Wei Tchen’s book The Chinese Laundryman A Study of Social Isolation, a comparison of the distribution of Chinese laundries on city maps from 1874 and 1913 reveals that they were initially concentrated around Madison, Clark, State, and Randolph Streets—what is now known as the Loop. Those locations reflect where Chicago’s Chinese community lived during that time—in 1890, 25 percent of the city’s 600 Chinese lived along Clark between Van Buren and Harrison Streets. The distribution of Chinese laundries expanded outward from the center of the Loop, reaching as far north as Rogers Park, as far west as Jefferson Park, and as far south as Roseland by 1930.

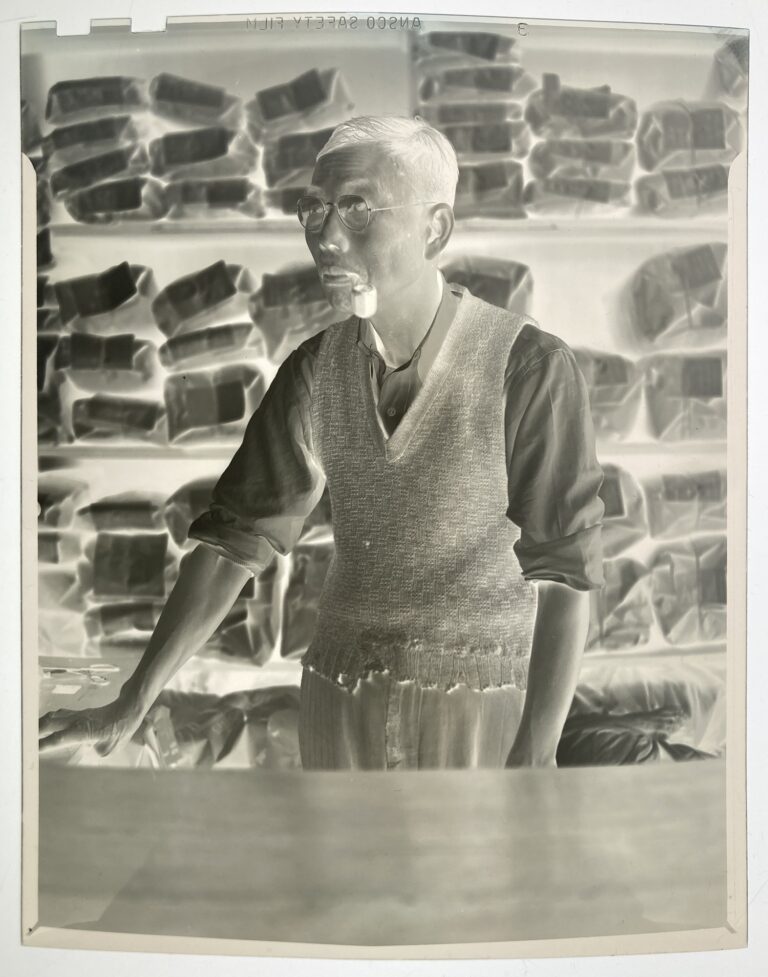

In 1928, the number of Chinese laundries peaked at 704 in the United States. (3) Lyle Mayer’s 1948 photograph collection, taken in the vicinity of Roosevelt University, which was housed within the Auditorium Building on South Michigan Avenue in the Loop, features two photographs of a Chinese laundry. This negative depicts an elderly laundryman standing in front of a cabinet full of paper packets.

Negative of a Chinese laundryman, Chicago, April 5, 1948; Lyle Mayer, photographer. Lyle Mayer Photograph Collection, CHM, Box 2, Unit #46, S4363. Call Number 1986.0207.

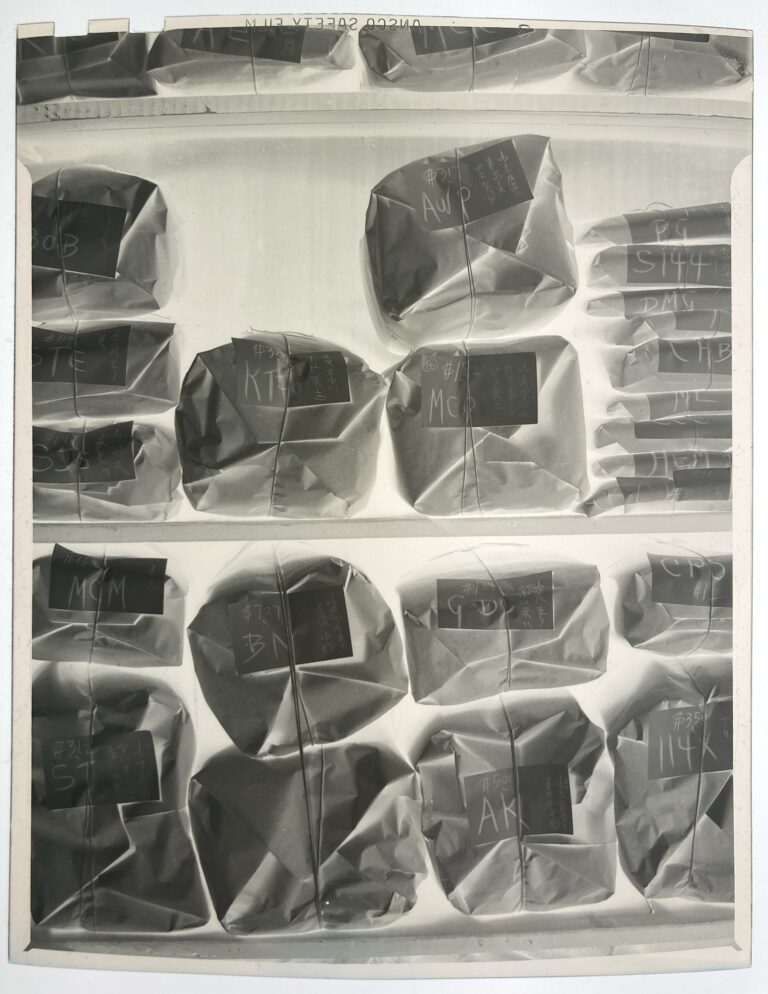

A closer look reveals that each paper bag was secured with string and included a slip of paper bearing the customer’s name, allowing the efficient retrieval of laundered clothing. This laundry is a relatively spacious example. The size and environment of each laundry were usually influenced by the surrounding neighborhood. In an underserved community, a typical shop would have one person working behind a counter protected by security bars.

Negative showing packet packets of laundry at a Chinese laundry, Chicago, April 5, 1948; Lyle Mayer, photographer. Lyle Mayer Photograph Collection, CHM, Box 2, Unit #46, S4364. Call Number 1986.0207.

As we move south in the city, Mildred Mead’s 1956 photograph showcases the Hong Sing Hand Laundry located in the Hyde Park-Kenwood neighborhood. Similar to Mayer’s photographs, this location’s proximity to the University of Chicago suggests a recurring pattern of clustering near apartments that accommodated young individuals or white-collar office workers.

Hong Sing Hand Laundry at 5025 S. Lake Park Ave. in the Hyde Park-Kenwood neighborhood, Chicago, April 18, 1956. CHM, ICHi-087921. Mildred Mead, photographer

Nowadays, traditional hand laundries are disappearing in Chicago and across the United States, and even those owned by Chinese Americans are transitioning into laundromats. Rather than casting them as a stigmatized relic of the past, I want to underscore their significance as life-saving opportunities for immigrants. Moreover, they were catalysts for protests and labor unions, contributing significantly to the story of Chinese Americans’ quest for equality in the United States. For those who are interested in this topic, the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance is a worthwhile starting point.

Footnotes

- Iris Chang, The Chinese in America: A Narrative History (New York: Penguin Publishing Group, 2004), 49.

- Paul C. P. Siu and John Kuo Wei Tchen, The Chinese Laundryman: A Study of Social Isolation (New York: NYU Press, 1987), 23.

- Siu and Tchen, 34.

Additional Resources

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Laundries and Laundering

- Read ABC7 News, “Why Chicago’s Chinatown is growing as others see Asian populations decline,” May 18, 2022.

In this blog post, editor and content manager Heidi Samuelson looks at the 1971 Mayday Protest and anti-Vietnam war actions in Chicago in advance of the opening of Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s–70s.

The Vietnam War sparked a massive antiwar protest movement throughout the United States beginning with demonstrations in the mid-1960s. Chicago became a major center of antiwar activity during this time. Perhaps most notable were the protests prior to and during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. These protests led to a federal investigation, and eight demonstrators (known as the Chicago Eight, later Seven) were famously charged with conspiring to use interstate commerce with intent to incite a riot.

Demonstrators confront the National Guard during Democratic National Convention, Chicago, August 1968. ST-17100140-0003, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

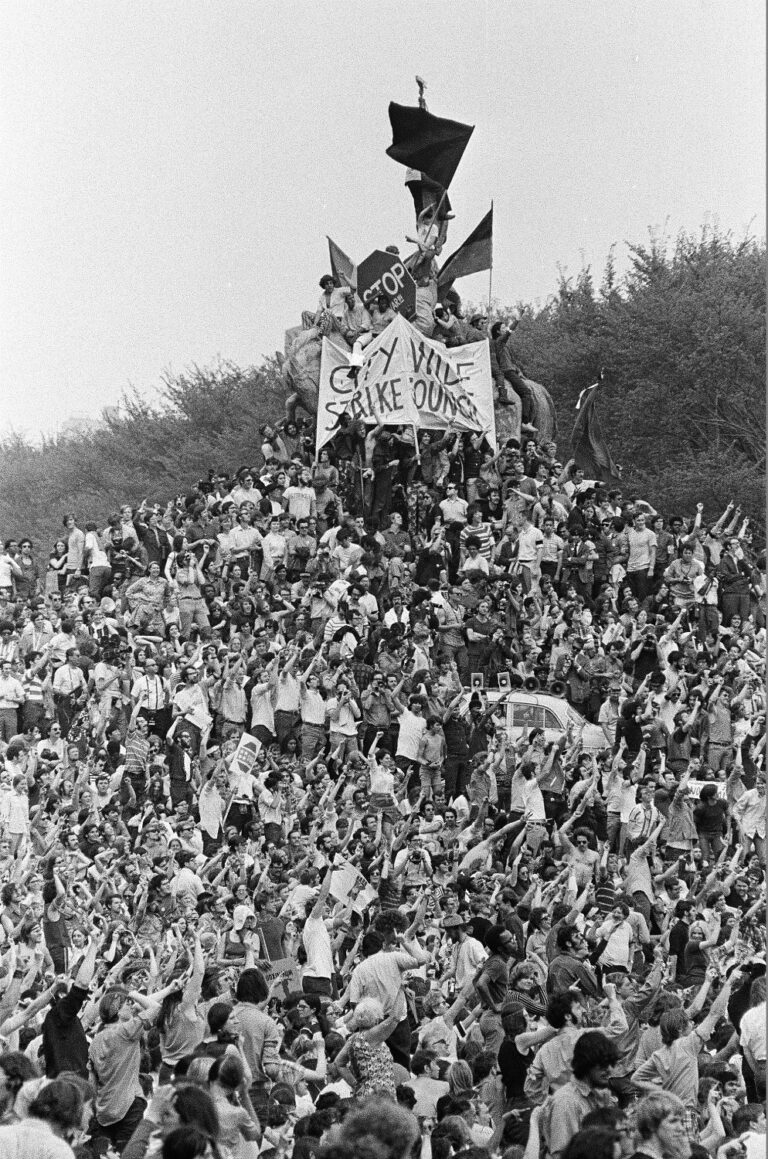

Although one of the leading student activist groups that focused on antiwar actions, the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), had split by 1969, the antiwar movement continued into the 1970s. Opposition to the war escalated after the Nixon administration ordered US ground troops to invade Cambodia on April 28, 1970. On May 4, 1970, four students at an anti-Vietnam War rally at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, were shot and killed by National Guardsmen. The following day in Chicago, thousands of people, primarily university students, filled Grant Park in protest.

Women for Peace gather at the Federal Building, 219 South Dearborn Street, Chicago, before a march begins in protest the Kent State University student deaths and American action in Cambodia. The march began at the Federal Building and ended at the General John A. Logan statue in Grant Park. ST-10003874-0011, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Following the Kent State shootings, students gathered in Grant Park around the John Alexander Logan Monument in protest of the Kent State University shootings and the Vietnam War, ST-14002662-0004, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

A year later in 1971, the activist landscape was fractured, but May 1 still saw the largest act of civil disobedience in US history—as well as the largest mass arrest. Known as the Mayday Protest, the plan was, simply, to shut down the federal government. Under the slogan “If the government won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government,” organizers detailed in advance 21 bridges and traffic circles in Washington, DC, for protesters to block nonviolently with vehicles, makeshift barricades, or their bodies. The immediate goal was to prevent government employees from getting to their jobs, but the larger aim was, as stated in the Mayday Tactical Manual, “to create the spectre of social chaos while maintaining the support or at least toleration of the broad masses of American people.”

Rennie Davis celebrating release of Chicago Seven at Harper Court Restaurant, Chicago, 1969. Photographed for essay in Scanlan’s Magazine. CHM, ICHi-175702; Stephen Deutch, photographer

One of the organizers of the action was Rennie Davis, one of the Chicago Seven, who took the idea of a nonviolent blockade from a failed attempt of the Brooklyn Chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to stop traffic on the opening day of the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Unlike many organized actions, the Mayday Protest had a decentralized structure. Rather than taking orders from leaders, tactics were shared among different “regions” of the planned action and were followed by small affinity groups.

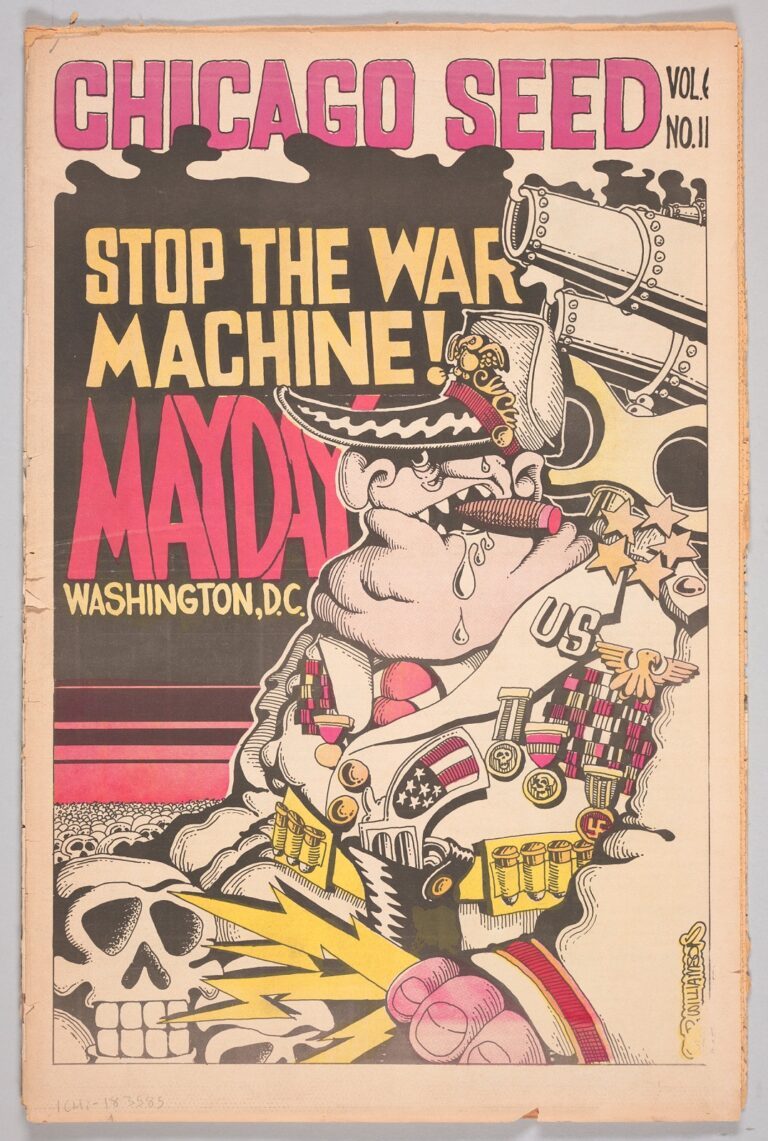

The protest was supported by the Chicago Seed. Established as a collective in 1967, the Seed started as a newspaper about local counterculture. But police action at the 1968 Democratic National Convention radicalized the staff, and they began to focus on more serious issues, particularly the Vietnam War. At its height, the Chicago Seed, which could be purchased for 35 cents at newsstands, reached 30,000–40,000 readers, making it one of the nation’s most widely circulated and influential underground newspapers before it ceased operations in 1974.

The cover of Chicago Seed, vol. 6, no. 11, “Stop the War Machine” by the underground cartoonist Mervyn “Skip” Williamson, was designed to rally support for the 1971 Mayday Protests in Washington, DC. CHM, ICHi-183585; Skip Williamson, artist

Ultimately, the Mayday Protests weren’t widely considered a success. Many of the planned blockades only held for a short time, and in some cases, protesters were arrested en masse before they even got to the blockades. However, the sheer size of the action did send a message to the Nixon administration, which, according to CIA director Richard Helms (quoted in Tom Wells’s The War Within: America’s Battle over Vietnam) was “one of the things that was putting increasing pressure on the administration to try and find some way to get out of the war.”

Additional Resources

- Chicago: Law and Disorder online exhibition

- 1968 Oral History Project: “I Was There”

- The Chicago 7 Trial blog post

- “The Whole World is Watching” blog post

To mark National Day of Puppetry, CHM research center associate Annika Kohrt writes about the mother-son duo of Esther and Ernest Wolff, who established Chicago’s puppet opera scene in the 1930s.

Chicagoans in the first half of the 20th century loved to miniaturize things. From Narcissa Niblack Thorne’s Miniature Rooms to Frances Glessner Lee’s Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, Chicagoans were using miniaturization to relate to the burgeoning city and modernizing world around them. Even the Chicago History Museum was making miniatures in the 1930s: our seven dioramas illustrating Chicago’s history are the longest-displayed artifacts at the Museum.

The city’s arts and performance scene also saw a particularly delightful miniaturization: Puppet. Opera.

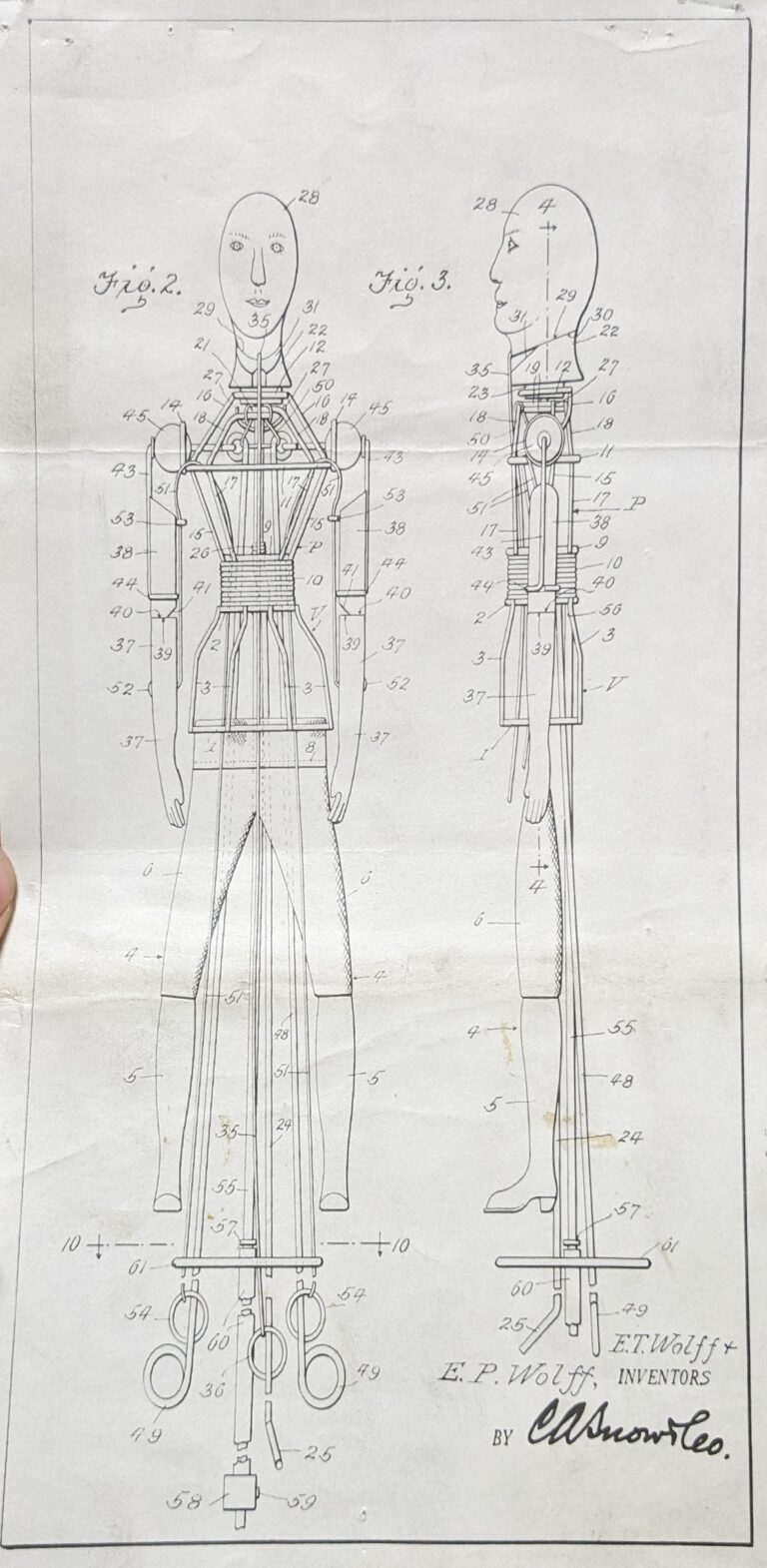

In 1932, the Great Depression bankrupted the Civic Opera Company, and the Lyric Opera didn’t begin operations until 1952. Filling that twenty-year gap with magic and playfulness was a company with a handful of opera records and a cast of hundreds of puppets, created and operated by Esther Theresa Wolff and her son, Ernest. The duo invented an intricate rod puppet, which was operated by puppeteers on wheeled stools underneath the stage.

(From left) Ernest P. Wolff and Esther T. Wolff patent illustrations, CHM, Chicago Miniature Opera Company records [manuscript], ca. 1930-1971. Box 1. Bib#65102; undecorated wire puppet form constructed by Ernest P. Wolff for the Chicago Miniature Opera Theater, c. 1940, CHM, ICHi-175086; puppet depicting Brünnhilde from the opera Die Walküre; this puppet was included in Ernest P. Wolff’s Chicago Miniature Opera Theater, c. 1940. CHM, ICHi-175101

Victor Puppet Opera Troupe: (left to right) Evonne Moller, director of the ballet; Gretel Foerster; Mrs. E. Theresa Wolff, chief operator and mother of the director; and Roberta Haase, assistant, Chicago, c. 1942. CHM, ICHi-016388

Combining puppets and opera involved the creation of delightful characters along with the Wolffs’ marvelous talents. Mrs. Wolff was a widowed Czechoslovakian mother with a background in stage costuming. She was a huge opera enthusiast. CHM’s collection includes several scrapbooks of her programs and newspaper clippings of live Chicago operas, and later all the performances and reviews of the miniature opera. Well indoctrinated into a love of opera, Ernest was making miniature opera sets in a fruit crate in the family’s basement at age 12.

Clipping from Popular Science article by Arthur Stuart, April 1940; CHM, Chicago Miniature Opera Company records [manuscript], 1930–71. Box 1. Bib#65102

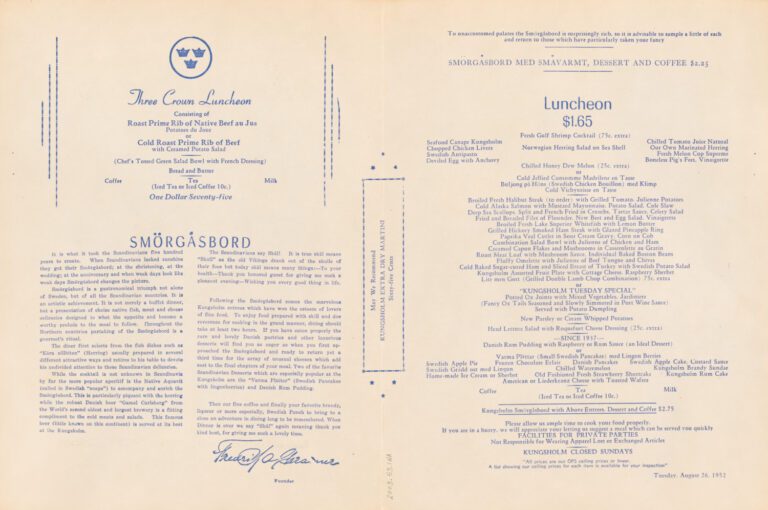

Soon, they were performing full shows around the Midwest to great reviews. The company had a residency at the 1939–1940 New York World’s Fair, where they gained national recognition. After the world’s fair, Ernest decided to serve in World War II. Before he left for Europe, Fredrick Chramer, owner of the Kungsholm Restaurant, saw a puppet performance, and asked to partner. In short order, the puppet opera was permanently installed at the Kungsholm. Fantastical matinees and evening shows were available for children and adults alike, alongside luxurious Scandinavian smörgåsbord dining.

(From left) Kungsholm luncheon menu, July 2, 1952, CHM, ICHi-085972-003; interior view of the lobby of the Kungsholm Miniature Grand Opera, July 18, 1952, HB-15100-C, CHM, Hedrich-Blessing Collection

When Ernest returned to Chicago, it was to a successful puppet opera theater, but it was missing one crucial element: his name. He successfully sued Chramer for not crediting him, then took his settlement, and he and his mother started their own puppet theater once again. He made several TV appearances and had a brief residency at the Hyde Park Hotel, but the theater didn’t take off, and he quit puppetry to go into banking.

Meanwhile, the Kungsholm Miniature Grand Opera was evolving and had become a world-renowned landmark. It was the starting point for two puppeteers: Gary Jones, founder of Blackstreet USA Puppet Theatre, and Bill Fosser, founder of Opera in Focus in Rolling Meadows, Illinois, where you can still see these puppets perform. The Kungsholm puppet opera ultimately closed in 1971. Gary Jones purports that this was partly because of competition from the “real life” Lyric Opera and partly because of declining production quality after the Fred Harvey chain bought the Kungsholm in 1957.

At the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is always free to visit, you can view historic photos, programs, and menus from around Chicago. It’s a real smorgasbord of magic and delight—it might even inspire your next puppet show.

Additional Resources

- Subplot: Memoirs of Chicago’s Kungsholm Miniature Grand Opera

- Luman Coad

- Opera in Focus

- Chicago Miniature Opera Manuscripts

“In seas. In windsweep. They were black and loud.

And not detainable. And not discreet.”

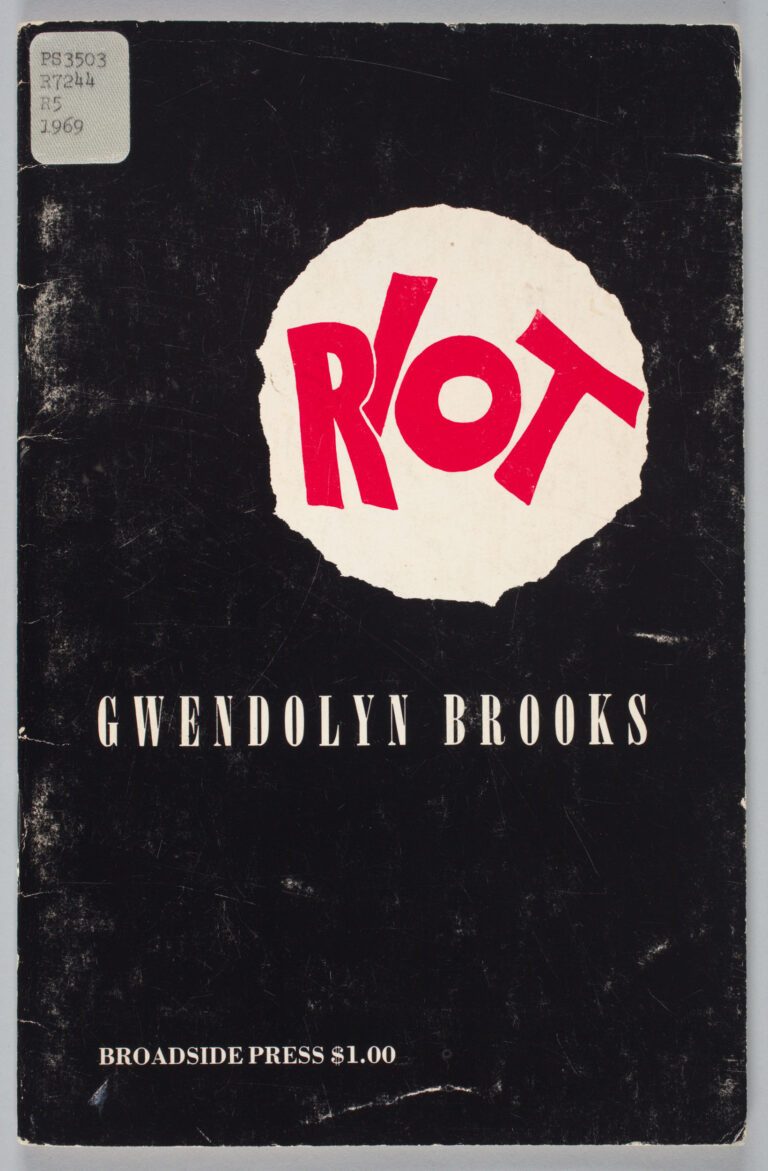

— Gwendolyn Brooks, Riot (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1969)

As the Digital Humanities Curatorial Fellow at CHM charged with developing digital storytelling initiatives using the Museum’s collections items, I face questions about language within metadata (detailed information on an item to help users discover resources) daily. One particularly charged term appearing throughout the digitized collections is “riot.” CHM is currently undergoing a critical analysis of riot terminology within our descriptive metadata—found in the ARCHIE catalog records, CHM Images, and other digital resources used by researchers—with the intention of updating records to represent their historical content more equitably. Language changes, such as the ones for “riot” and “uprising,” fall under the umbrella of CHM’s Critical Cataloging initiatives. This blog post considers Chicago’s “riot” history, the term’s use within the descriptive metadata of digitized collections items at CHM, and best practices for appropriate use and corrective language.

Cover of Riot by Gwendolyn Brooks, 1969. CHM, ICHi-182532b

Perhaps the most iconic usage of the term “riot” is in the title of Gwendolyn Brooks’s three-part poem, published by Broadside Press in January 1969. In Riot, Brooks describes the global Black community’s response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Brooks’s poem gives meaning to a community “in windsweep,” “black and loud,” as does the frontispiece “Allah Shango” (not pictured) by AfriCOBRA artist collective cofounder Jeff Donaldson. In the painting, two young Black men are shown both trapped behind, and shattering through, a glass window. Brooks’s poetry and Donaldson’s painting depict rioting as a strategy for gaining access to that which has been rendered inaccessible, for giving voice to issues that have been systematically silenced. According to historian Felix M. Padilla, riots follow a pattern: following an influx of population, there are increases in racial violence and legislative acts to prevent movement into white neighborhoods. Overcrowding, disease, police brutality, and violence create the psychological climate for rioting.

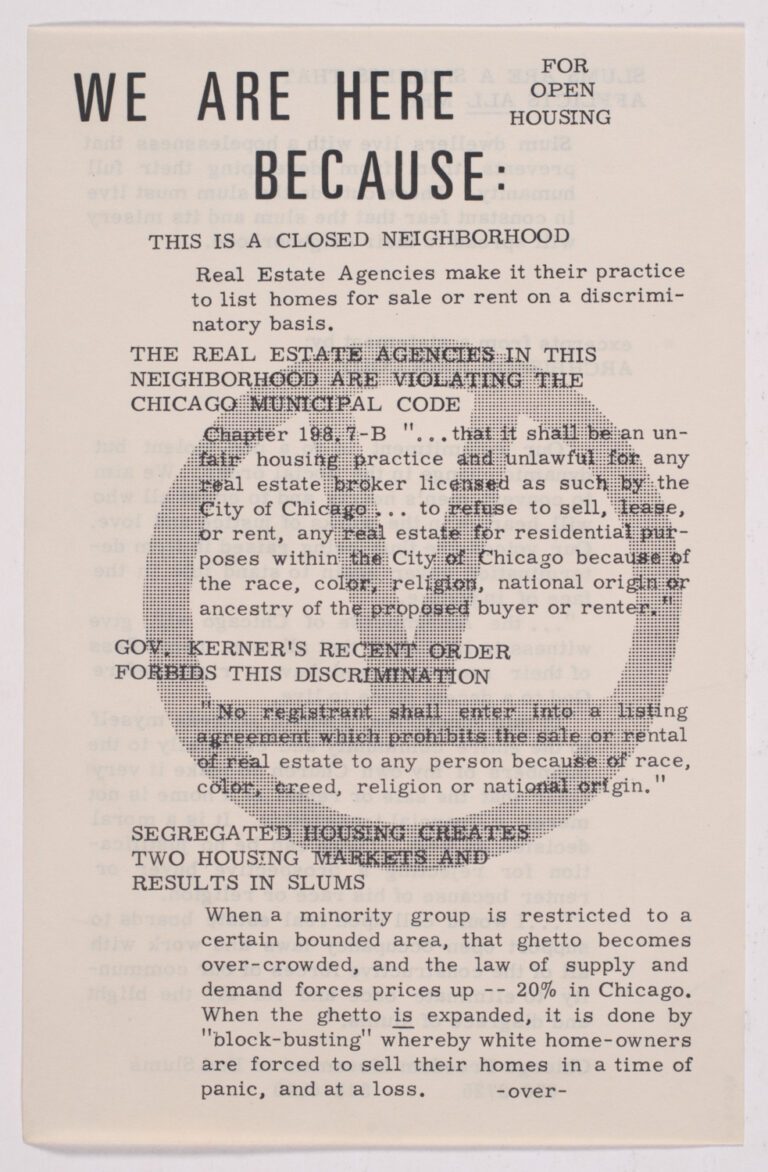

For Black communities of Chicago in the 1960s, this included limited access to adequate housing, health, education, and employment, illuminated by Dr. King when he moved to North Lawndale in 1966 to work with the Chicago Freedom Movement. Visuals created by the Chicago Freedom Movement such as the “MOVE” logo highlight the power of art and design as an agent of protest and advocate for social justice. CHM’s upcoming exhibition, Designing for Change: Protest Art of the 1960s‒70s, explores how Chicagoans used art to advance the Chicago Freedom, Black Power, anti-Vietnam War, women’s liberation, and early LGBTQIA+ movements. Dr. King and the Chicago Freedom Movement used design to visually engage audiences, raise awareness of poor living conditions, and fight against blockbusting, predatory lending, and the dual housing market.

Left: Recto of Chicago Freedom Movement flyer, We Are Here Because, opposing discriminatory real estate practices, Chicago, 1966. CHM, ICHi-183258-001. Right: Cover for the program for the Chicago Freedom Festival with Chicago Freedom Movement symbol on front cover, sponsored by Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations, held at the International Ampitheatre, 4220 South Halsted Street, Chicago, March 12, 1966. CHM, ICHi-182985

Photographs depicting the civil response to King’s murder, known as both the “King Assassination Riots” and “Holy Week Uprising,” speak to the complexities of language. Images of burning and vandalized buildings, shattered storefronts, littered streets, and armed guards inspire visceral responses from their viewers. But as asserted by Darnell Hunt, Dean of Social Sciences and Professor of Sociology and African American studies at UCLA, the terms “rioting” and “looting” connote senseless violence and crime and diminish or obscure the underlying racial oppression and demonstrative purposes of such acts. According to activist Toivo Asheeke, the term riot “holds an inordinate amount of importance on whether one interprets events as justified or not.” Furthermore, the word riot has become a racist trope, according to Dr. Elizabeth Hinton, applied to events properly understood as uprisings or rebellions, that is, collective resistance against an unequal and violent order.

Though sometimes used interchangeably, riot, rebellion, protest, and uprising have been loaded with racial connotations by the media and public throughout history. It is not only who, but how these events are depicted, that generates meaning for viewers. In 2018, previously unsurfaced photographs of the days after King’s assassination taken by Karega Kofi Moyo were displayed at a gallery in the Pilsen neighborhood in the Lower West Side community area. The photographs show a unique perspective of the event compared to the mainstream (white) media publications to date, including an image of a lone young boy covering his face near a group of armed guardsmen in gas masks. Photographs like these illustrate the military-backed violence committed toward the Black community, a tragic and deadly reality of uprisings that is undermined by the term “riot.”

A National Guardsman aims his rifle on West Madison Street during riots following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Chicago, April 6, 1968. ST-17500739-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

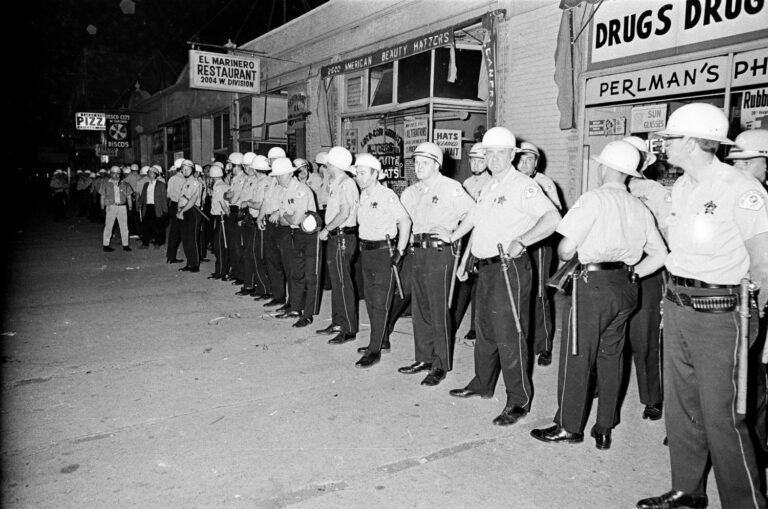

When used to describe collective events in Chicago history with distinctive motives and outcomes, the term riot sends conflicting messages. The digitized Chicago Sun-Times collection at CHM, and its descriptive metadata, shed light on this issue. Of the digitized images in this collection, 640 contain the word “riot” in their metadata, and 17 contain the word “uprising.” The term “riot,” often transcribed from the photographer’s original caption, was used to describe the 1919 Chicago Race Riot, the 1966 “Puerto Rican/West Side riots,” the 1977 “Humboldt Park riots,” the 1968 “Democratic Convention riot,” and the 1968 “Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination riots” alike, despite their varied motivations and outcomes. The Chicago Sun-Times collection is part of the archives that CHM is currently studying to specify terminology and correct such conflations.

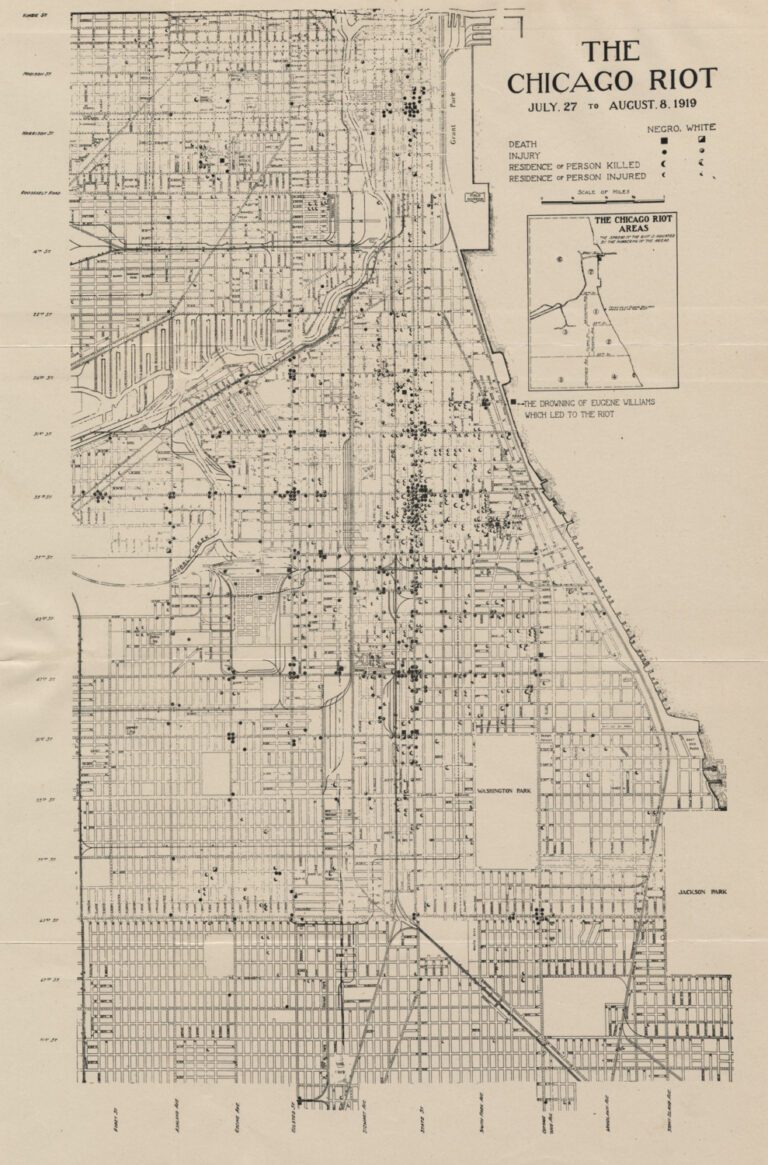

Left: Neighborhood children raiding an African American family’s house after they were forced out during the 1919 Chicago Race Riots, Chicago, 1919. CHM, ICHi-040052; Jun Fujita, photographer. Right: Map of titled The Chicago Riot indicating that most of the fighting occurred between 35th Street and State Street from July 27 to August 8, 1919. CHM, ICHi-040053

In the first half of the twentieth century, riot was frequently used to describe white mobs committing violence against Black people and homes. Following the murder of Eugene Williams by a white mob for floating into a “white” beach, and the violence that erupted into the 1919 Chicago Race Riots, more than 2,800 officers surrounded the Black Belt (a corridor of predominantly Black neighborhoods along State Street), effectively concentrating the violence and its material effects within Chicago’s Black community. Black people were charged with crimes at double the rate as white people, despite suffering two-thirds of casualties resulting from the riot.

Police presence during riot in Puerto Rican community on Division Street near Hoyne Avenue, Chicago, June 13, 1966. ST-11007177-0006, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

In the 1960s the term riot was applied instead to insurrections against police and institutions, as with the “1966 Puerto Rican/West Side riots.” With the planned redevelopment of Lincoln Park and expansion of DePaul University’s campus in the 1950s and ’60s, Puerto Rican residents were pushed out from their homes and neighborhoods into overcrowded and unsanitary areas to the west. As a response to organized displacement and police brutality against Puerto Rican communities, the 1966 West Side “riots” were motivated by oppression—and therefore, appropriately understood as a “rebellion” or “uprising” distinct from racially-motivated violence like the 1919 Chicago Race Riots.

Members of The Woodlawn Organization (TWO) picket outside of the Polish Roman Catholic Union offices, 984 North Milwaukee Avenue, regarding the desperate need of maintenance work on a 20-unit apartment building in the Woodlawn community area, Chicago, June 11, 1964. ST-10003494-0014, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

As historians, we must be cautious of language used to analyze, marginalize, or mischaracterize the racially discriminated, poor, or disenfranchised, in the past. This includes making distinctions between riot and uprising, one connoting senseless violence, and the other, a collective fight against oppressive systems. Similarly, we must question terms like “ghetto,” “slum,” and “underclass,” which, as with “riot,” have not only been used to describe existing conditions but have contributed to neighborhood disinvestment and decline.

Bibliography

- Paul Bisceglio, “There’s a Difference between Riots and Rebellion,” UCLA Newsroom, July 13, 2015.

- Chicago History Museum. “It Was a Rebellion: Chicago’s Puerto Rican Community in 1966.” Google Arts & Culture.

- Alia E. Dastagir, “’Riots,’ ‘Violence,’ ‘Looting’: Words Matter when Talking about Race and Unrest, Experts Say,” USA Today, May 31, 2020.

- KT Hawbaker, “K. Kofi Moyo Exhibits Scenes of Resistance from Chicago’s Past that Mirror the Present,” Chicago Tribune, August 16, 2018.

- Elizabeth Hinton, America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s (New York: Liveright, 2022).

- Ann K. Johnson, Urban Ghetto Riots, 1965–1968 (East European Monographs, 1996), distributed by Columbia University Press.

- Felix M. Padilla, Puerto Rican Chicago (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1987).

- Abigail Perkiss, “The Language of Protest: Race, Rioting, and the Memory of Ferguson,” Yahoo! News, December 3, 2014.

- Ben Railton, “What We Talk About When We Talk About ‘Race Riots,’” Talking Points Memo, November 25, 2014.

- Carl Sandburg, The Chicago Race Riots (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1919).

- Jackie Spinner, “Fifty Years after Chicago ‘Riot,’ New Photos Emerge—and Develop a Story,” Columbia Journalism Review, March 7, 2018.

- Heather Ann Thompson, “Urban Uprisings: Riots or Rebellions?” in The Columbia Guide to America in the 1920s (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 109–17.

- William M. Tuttle, “Contested Neighborhoods and Racial Violence: Prelude to the Chicago Riot of 1919,” Journal of Negro History 55, no. 4 (1970): 266–88.

- David Wyatt, “Chicago,” in When America Turned: Reckoning with 1968 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 231–54.

- Heather Yarrish, “White Protests, Black Riots: Racialized Representation in American Media,” Young Scholars in Writing 16 (August 2019): 6–24.

Passover 2024 begins at sundown Monday, April 22, and ends at sundown on Tuesday, April 30. In this blog post, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman writes about the Chicago Loop Synagogue and a Passover Seder shared by its rabbi, Irving Rosenbaum, in 1966.

A Seder table with Rabbi Irving Rosenbaum (seated, center) and his sons at Chicago Loop Synagogue, March 31, 1966. ST-11005561-0005, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

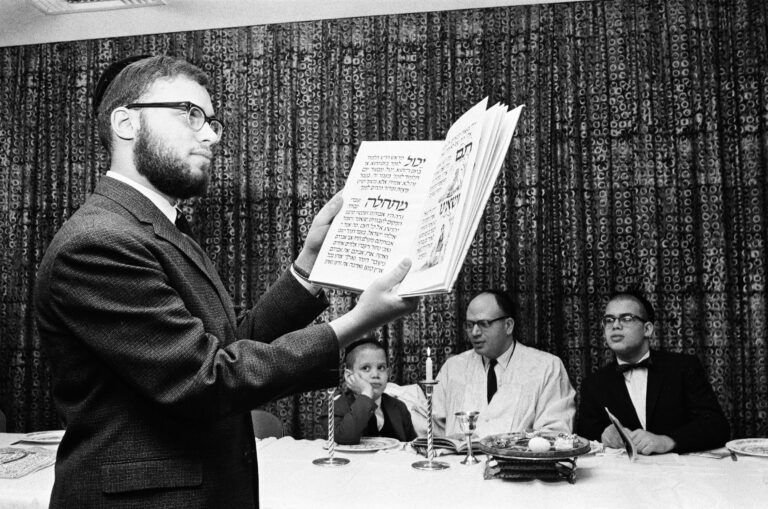

This set of images shows a staged Passover meal taking place at the Chicago Loop Synagogue in 1966. Featured center is Roy Rosenbaum (age 19) reading to his father, Rabbi Irving Rosenbaum, and his two brothers, Alan (age 6) and Don (age 15). Roy is holding a Haggadah, a book that details the order of the Passover meal, known as the seder (seder, in fact, means “order”). It outlines stories from the Book of Exodus and includes a series of blessings, songs, actions, and ceremonial foods and drinks as a guide for families and communities through the symbolic meal.

Roy Rosenbaum reads from a Haggadah during a Seder at Chicago Loop Synagogue, March 31, 1966. ST-11005561-0001, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Roy is reading pages from a section in the seder that discusses four sons or four children: the wise, the wicked, the simple-natured, and the one who doesn’t know how to ask. These children represent different ways of approaching and learning about the story of Passover. The Haggadah next shares the Exodus story as a movement from slavery toward freedom. While seders are often something done at home with family, they may also be done in synagogues or in larger community, all with an emphasis of passing the story through the generations and recalling humankind’s search for freedom.

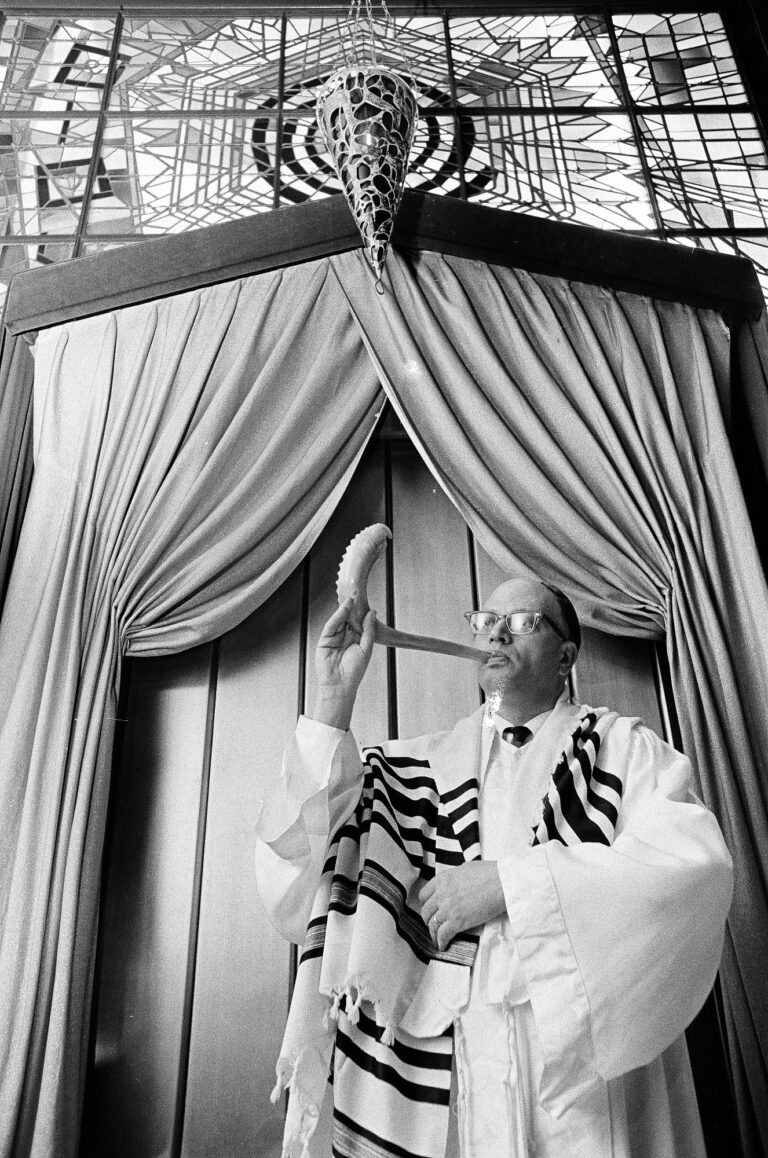

Rabbi Irving J. Rosenbaum blows a shofar during Rosh Hashanah services at the Chicago Loop Synagogue, September 20, 1968. ST-11005551-0007, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Rabbi Irving J. Rosenbaum (c. 1922–2005) served as rabbi of Chicago Loop Synagogue for 14 years. Born in Omaha, Nebraska, Rabbi Rosenbaum moved to the Chicago area for school at age 16. He attended the University of Chicago in Hyde Park and Hebrew Theological College in Skokie, graduating in the 1940s. In 1946, he served as the National Director of the Department of Interreligious Cooperation for the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith. Rabbi Rosenbaum was especially dedicated to education, including in interfaith settings. For example, he produced a film and accompanying booklet for non-Jews called Your Neighbor Celebrates to explain Jewish religious practice and holidays. This fervent interest in religious education was passed down to the next generation, as all three of his sons would go on to also become rabbis.

Chicago Loop Synagogue as seen from Clark Street, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Chicago Loop Synagogue was founded in 1929 to provide a space for Jewish professionals working downtown. The community began by renting different spaces around the Loop for daily and Friday evening (Kiddush) prayers. In the 1950s, they were inspired to construct a purpose-built synagogue after seeing Temple Har Zion in River Forest, Illinois, completed in 1951. They commissioned Har Zion’s architects—Loebl, Schlossman, and Bennet—to design their current building on South Clark Street between Madison and Monroe Streets, completed in 1958.

Today known as Loebl, Schlossman, and Hackl, the synagogue designers’ firm was founded in 1925, with the practice’s name shifting in passing decades as new partners and collaborators joined and left over time. Their founding namesakes, Jerrold Loebl and Norman Schlossman, had grown up in Hyde Park and both studied architecture at Armour Institute of Technology (today Illinois Institute of Technology). Richard M. Bennet, who was originally from Pennsylvania and had studied at Harvard University, joined Loebl and Schlossman in 1947, shifting the practice’s name to Loebl, Schlossman and Bennet for the next two decades until joined by a fourth architect, Edward Dart, in 1965. They designed several impressive synagogues, including Lakeview’s Temple Sholom (1928), but their legacy extends much further through various planned projects and urban renewal schemes, especially in the Bronzeville neighborhood, as well as public housing, suburban developments such as Park Forest, and downtown Chicago’s Richard J. Daley Center.

Left: Women speak to the congregation regarding Soviet Jews at the Chicago Loop Synagogue, December 10, 1979. ST-60002959-0001, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM. Right: Loop Synagogue sanctuary interior, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Loop Synagogue was designed not only to be architecturally and artistically beautiful but also includes layers of symbolic meaning as well as practical design to facilitate Orthodox Jewish needs. Two primary examples of this are in the main worship space. First, in place of an elevator, a long ramp leads between the first and second story to facilitate easy access for congregants unable to use the stairs. Since a traditional elevator uses electricity, its use would be prohibited on Shabbat for Orthodox Jews, so the ramp permits moving between levels while aligning with this prohibition.

Stained glass window by Abraham Rattner in Loop Synagogue’s sanctuary, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Similarly, as lights also usually require electricity, the sanctuary’s east side has an extraordinary stained glass window that runs nearly floor to ceiling. Designed by Abraham Rattner and considered one of the finest windows of its kind, its impressive size also serves a practical purpose by letting in plentiful, colorfully filtered light. The window, called Let There Be Light, is based on the scripture Genesis 1:3 and includes symbolic and literal references to light, including flames as a symbol of Divine presence and a seven-branched Menorah symbolizing inner light.

View of the Ten Commandments in both Hebrew and English at the Chicago Loop Synagogue, May 21, 1969. ST-19042097-0003, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Another beautifully symbolic element sits at the threshold of the building, visible from the street and just inside the synagogue’s entrance doors. A sculpture of the Ten Commandments, both in English and Hebrew, acts as bridge from the outside world to the inside’s sacred space.

Hands of Peace sculpture by Nehemia Azaz above the entrance to Chicago Loop Synagogue, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Religious practice downtown has shifted dramatically in recent years, compounded with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a significant decline in membership for the synagogue. The synagogue’s community, led by President Lynn Zoldan, continues to think of creative ways to serve their Jewish congregation while welcoming new uses to help preserve the space for the future. Outside the synagogue’s entrance on Clark Street is Nehemia Henri Azaz’s impressive Hands of Peace sculpture, which places the outstretched hands of the priestly benediction said over congregants against a backdrop of its very words in both English and Hebrew, serving as a blessing for those outside passing by.

Further Reading

- Read the entry on Jews in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Read the entry on Judaism in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Read the entry on the Loop in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Read the blog post “Hag Pesach Sameach: Passover and Chicago’s Jewish Communities“

- View the HABS documentation for Chicago Loop Synagogue