Latest Posts

This summer, CHM collections intern Brittany Boettcher worked with senior collections manager Britta Keller Arendt to inventory items in our Decorative and Industrial Arts collection. In this blog post, Boettcher highlights some Civil War artifacts and explains how differences between Confederate bills answered the questions she had about where and when they were printed. CHM publications intern Lily Stachowiak helped organize and publish this blog post.

Inventory projects in museums are like opening up a box of chocolates because you have no idea what you’re going to find. Museums conduct regular inventories of their collections in an effort to improve intellectual control and track locations of artifacts throughout their facilities. The Decorative and Industrial Arts (DIA) collection at CHM comprises approximately 100,000 artifacts, most of which have not been inventoried in recent years. Over the course of the summer, our goal was to document the artifacts stored throughout one aisle of shelving units. We found a huge range of items such as souvenirs from the 1893 world’s fair, Day of the Dead figurines, and a picture frame made by Civil War POWs.

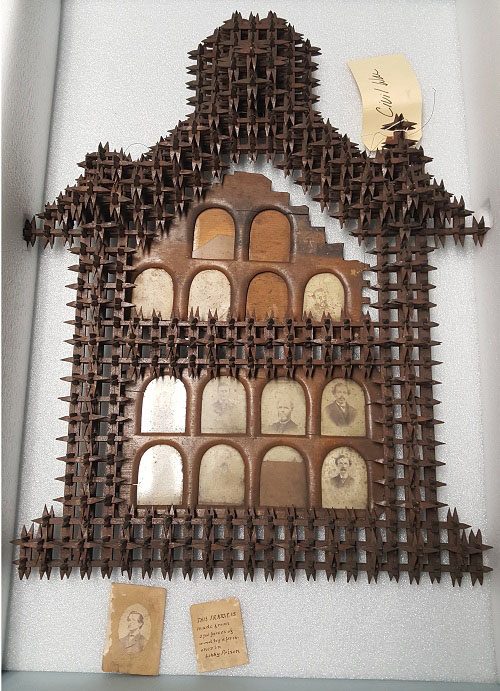

Union POWs at Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia, made this picture frame with iron nails. The photographs are called carte de visites (CdVs), which were popular during this era. All photographs by Lily Stachowiak

My fellow intern Cara Caputo and I learned something new every day as we cataloged our findings. Our tasks included inspecting objects, recording a description, take dimensions, and photograph them to add to or update the Museum’s digital records. This is so Museum staff can locate artifacts in the collection more easily and scholars can better research the collection. Throughout this process, it was important to be patient and detail-oriented. Sometimes we knew exactly what an object was, such as colonial currency from the Revolutionary War, but other times we needed to conduct research to learn more about the function or importance of the object.

For example, we slowed down when we found an envelope filled with twenty-one Confederate bills of varying sizes and denominations. Since they all came from southern states during the period of the Civil War and were in the same envelope in a box filled with other money, it was very tempting to take one picture and catalog all of them in one record. However, I realized it was important to take the time to study the bills individually—when I did so, it was clear the variations between them were likely significant.

Currency from various Confederate states in different denominations.

A close-up shot of two Confederate bills.

While these two bills can both be classified as Confederate currency, there are a number of important differences between them, includes size, design, printing date, and location.

During the Civil War, the government of the Confederate States of America printed its own currency that looked like the bills we found in our collection. Due to the limited amount of metal available at the time, only paper currency was printed. Also, the majority of printing presses were in the North, which meant that the Confederacy had a limited amount of design elements available for use. As a result, they reused familiar images and designs of goddesses of agriculture, commerce, and liberty, as well as important Southerners like Jefferson Davis and his cabinet members. Eventually, individual states, banks, and even private citizens started printing their own bills. The combination of inflation, a lack of gold and silver to back the money, and the Confederacy’s loss in the Civil War made these bills almost worthless. Nevertheless, the different designs, print dates, and sources of these paper bills can help identify the political and social environment in which they were created, the rarity of these bills, and much more.

Because of the significance of the various designs, we took time to update records and take individual pictures of each bill. If we had quickly grouped them together in a record and taken one photograph of all the bills, it would be harder for others to study them. Working with these bills taught us patience, which we used throughout the rest of the project. This internship also taught me more about history and good practices for collections management. I can only hope our effort and attention to detail will someday help others learn more about history through our collection.

- Read more blog posts about CHM’s inventorying efforts

- For more about Confederate and other historic currency, check out the National Museum of American History’s online exhibition

CHM digital content manager Julius L. Jones discusses the circumstances in 1968 that set the stage for a momentous event as well as the latest virtual reality experience from the Chicago ØØ Project.

By the time Chicago hosted the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the city was the center of the American political world. Since 1904, Republicans had held their nominating convention in the city nine times and Democrats six times. Although the city had been firmly in the hands of Democratic leadership for several decades, the state was a competitive swing state in presidential elections, having gone for the winning candidate in every election since 1920. Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley and the national Democratic party hoped that by hosting their political convention in Chicago, they could win the state and the reelection for president Lyndon Johnson in 1968.

History, however, intervened. As the war in Vietnam became increasingly unpopular and unrest gripped the nation, Johnson surprised everyone by dropping out of the race. A spirited primary campaign saw New York senator Robert F. Kennedy emerge as the popular choice, only to be killed after winning the California primary on June 5. None of the remaining candidates captured the popular imagination quite like Kennedy. Dissatisfaction with the war effort, the perceived ineffectiveness of civil rights legislation, and the despair over the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. in April and Kennedy in June made the city a powder keg by August.

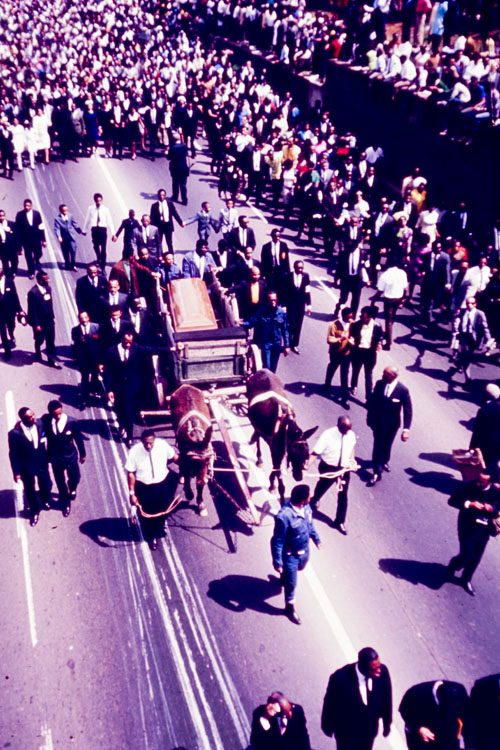

The funeral procession for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Atlanta, April 9, 1968. Photograph by Declan Haun, ICHi-173515

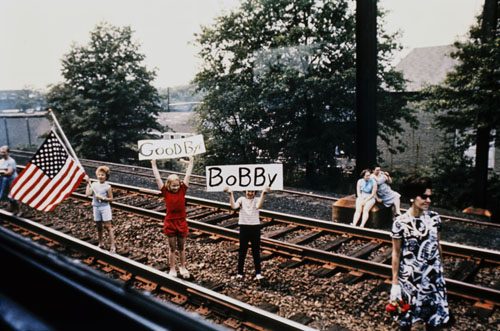

Children bid farewell to Robert F. Kennedy as his funeral train travels from New York to Washington, DC, June 8, 1968. Photograph by Declan Haun, ICHi-062718

In many ways, the protests outside the convention had as much to do with the absence of legitimate means to influence the electoral process than with the visceral opposition to the Vietnam War. Less than half the states in 1968 held primaries, meaning that the nomination was decided by party bosses who almost exclusively backed vice president Hubert Humphrey, ensuring him the nomination even though he did not compete in any of the primaries, leaving many voters feeling disempowered. Furthermore, Humphrey publicly supported Johnson’s war strategy despite his own personal reservations in order to appear strong and decisive as a potential commander-in-chief.

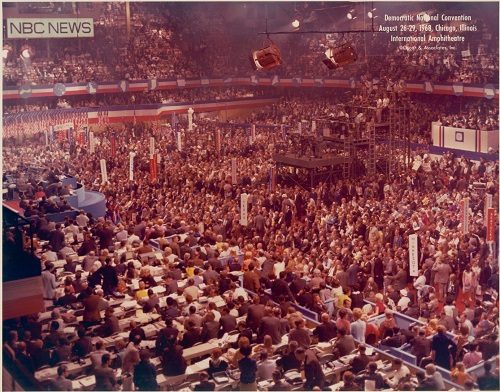

The scene inside the International Amphitheatre during the convention. Despite the best efforts of event organizers, the unrest in the city affected the proceedings inside. Chicago, August 26–29, 1968. ICHi-093668

As the convention began on Monday, August 26, at the International Amphitheatre, protestors congregated in Lincoln Park on the North Side and Grant Park downtown. Groups such as the Youth International Party, National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, Students for a Democratic Society, as well as local activist organizations all participated in demonstrations. With each passing day and night, the crowds grew until the evening of August 28, when the tensions could no longer be contained. The Chicago Police Department and Illinois National Guard moved in and the situation turned violent. As the police used force to disperse the crowd, a national television audience heard the protestors chanting, “The whole world is watching!”

The world was indeed watching, yet what the world saw differed from what the protestors hoped. Instead of sympathizing with the bloodied youths, the majority of Americans faulted the protestors for the chaos and respected the police and Daley for asserting order in the streets. The Republican presidential candidate, former vice president Richard M. Nixon, positioned himself as the “law and order” candidate and was able to carry Illinois and win the presidency eight years after losing it.

To mark the fiftieth anniversary of this event, the Chicago History Museum, in partnership with Geoffrey Alan Rhodes of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, created Chicago ØØ : The 1968 DNC Protests, a virtual reality experience. The fifteen-minute 3D VR tour with narration is made to be viewed on YouTube or on Facebook 360. On iPhone use the YouTube app; on desktop the Chrome browser. 360-degree stills can be explored on Google Street View.

- See more images of the event as well as courtroom sketches from the Chicago Seven trial

- Listen to oral histories of people who lived through the event

Known today as a Democratic Party stronghold, Chicago has ties to the Grand Old Party dating to Abraham Lincoln’s times. One twentieth-century GOP stalwart was Bertha Baur, who long made her home at 1511 Astor Street in the Gold Coast. National Republican Committeewoman for Illinois from 1928 to 1952, Mrs. Baur had a groundbreaking career as a business manager, fundraiser, suffragette, and Republican Party leader. A small collection of her papers at the Museum opens a window on numerous aspects of Chicago and national history.

Bertha Baur in 1926. Photograph by the Chicago Daily News, DN-008052

She was born Bertha Elizabeth Duppler in Mineral Point, Wisconsin, in 1871. Duppler arrived in Chicago at age seventeen, enrolled in business school, and before long was secretary to a succession of Chicago postmasters. It was generally understood that she ran the office when the postmaster was absent.

Duppler enrolled in Chicago-Kent College of Law and was the sole female graduate of the class of 1908. That same year, she married Jacob Baur, founder of the Liquid Carbonic Company, which provided soda water dispensers to the nation’s ice cream parlors and taverns. When he died in 1912, Mrs. Baur stepped in to help run the company. She served on its board of directors until 1926.

An undated photograph of Bertha Duppler (front, in white) in law school.

Mrs. Baur was a dedicated suffragette, helping to secure Illinois’ 1919 ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote. As a follow-up, she cofounded the League of Women Voters. She sold Liberty Bonds during World War I and chaired a committee that raised $1 million for the Civic Opera, a predecessor of today’s Lyric Opera.

In 1920, Mrs. Baur attended the Eighth Conference of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in Geneva, Switzerland. Here, a group of attendees pose for a photograph at the Hôtel de la Paix.

At the conference, women from thirty-six countries gathered to discuss full suffrage, civil equality, equal pay, and the welfare of women in all lands.

In 1952, Mrs. Baur was the official hostess for the Republican National Convention, held at Chicago’s International Amphitheater and Conrad Hilton Hotel. Her convention planning efforts and other party activities are well documented in the collection. A supporter of Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, she was likely disappointed when the convention nominated war hero Dwight Eisenhower. Mrs. Baur remained active in party affairs into her nineties, before passing away in 1967.

A staunch supporter of the Republican Party, Mrs. Baur enjoyed collecting hats adorned with elephants, such as this one by Bes-Ben.

Tucked away in the Bertha Baur papers is a letter demonstrating that Chicago in 1903 was not yet ready for reform. Graeme Stewart was the Republican candidate for mayor that year, and Jacob Baur had some advice for him: “P. J. King . . . is one of the Chief men concerned in the Policy game in the city . . . and can control with his money from 500 to 1,000 votes.” [original capitalization] With this collection, you can explore Chicago politics and Mrs. Baur’s varied activities. The Bertha Baur papers can be found in the Chicago History Museum’s Research Center, which is free to visit.

This past winter and spring, CHM collections interns processed the Museum’s Special Olympics Chicago records under the supervision of archivist Julie Wroblewski. Erin Glasco handled the manuscript material, while Ashley Clark handled the photographic portion.

The Special Olympics Chicago records detail the history and trajectory of the Special Olympics here since the first games were held at Soldier Field on July 20, 1968. The inaugural games were organized by Illinois Supreme Court Justice Anne McGlone Burke, who was then a twenty-three-year-old physical education teacher with the Chicago Park District, and Eunice Kennedy Shriver and the Joseph P. Kennedy Jr. Foundation. Burke conceived of the idea to hold sports competitions for her students after attending a seminar lead by Dr. William Freeberg, a physical education professor at Southern Illinois University, whose research indicated that providing physical fitness opportunities for children with disabilities could lead to improvements and opportunities in other areas of their lives. After the initial games, Shriver and the Kennedy Foundation took over the operations for what was eventually known as Special Olympics, Inc.

Burke (in plaid) at a Special Olympics award ceremony at Soldier Field in 1976.

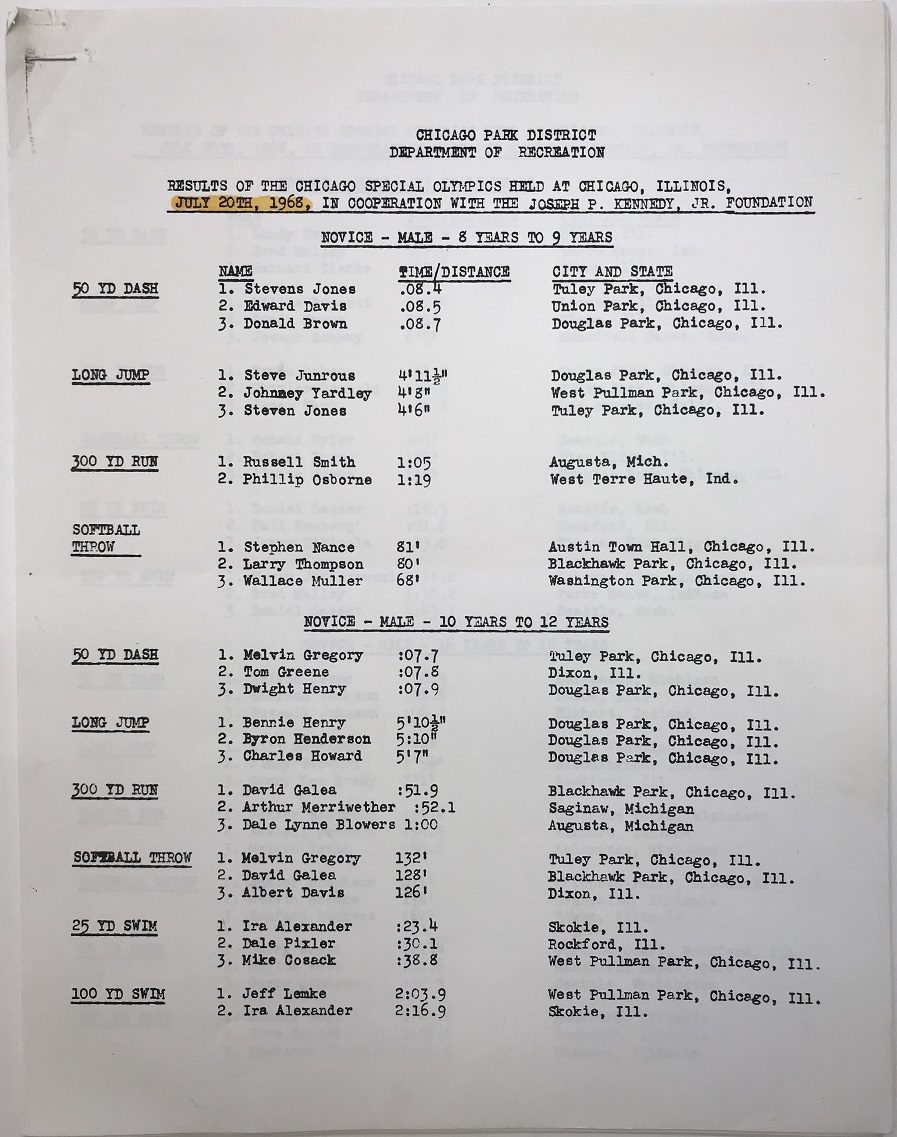

The manuscript portion provides a fascinating and comprehensive look at the planning of the first Special Olympics. It also contains programs and game results from a range of athletic and fundraising events held by Special Olympics Chicago and attended by local athletes as well as regional and state iterations of the games. There are also several letters and memos between Burke and Shriver highlighting the evolution of the management and scope of the institution and crediting Burke’s role in creating the event.

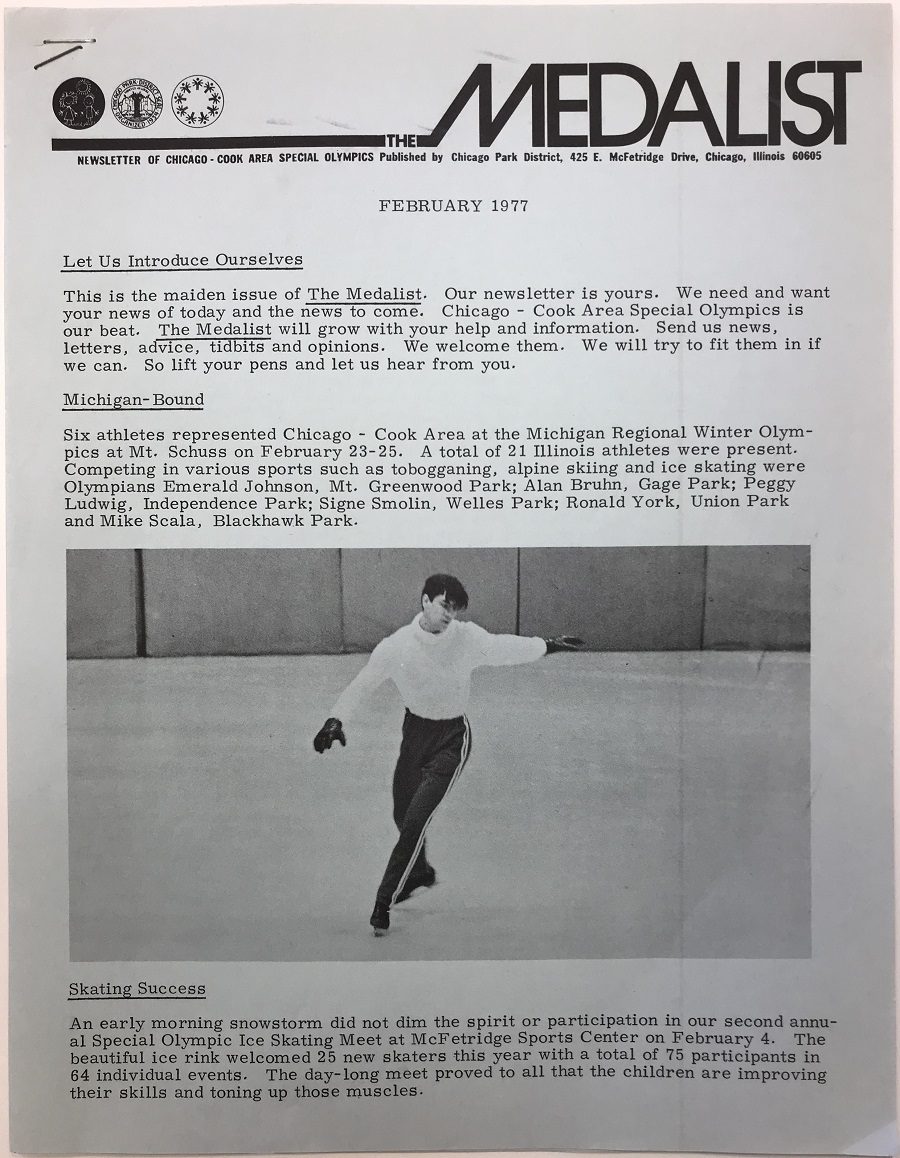

Documents in the collection include results from the first Special Olympics (above) and newsletters for Special Olympics Chicago.

The collection also has a large visual history of Special Olympics Chicago sports, events, and people, with more than 3,000 color and black-and-white prints. The images capture the various sports and opportunities that the Special Olympics offered, including common sports like track and field, swimming, basketball, gymnastics, and skiing, but also sledge hockey and broomball, from the earliest days into the 2000s. The photographs also show how the organization is more than just the annual competitions. Included are images of year-round events at Chicago parks, events for fundraising, and programs aimed at raising awareness of developmental disabilities. When seen together, the collection demonstrates the progression of Special Olympics from local to international in scope and the positive impact it has had on the children and adults who have participated and benefited from its services since its inauguration.

There is little doubt of the lasting, positive impact that Special Olympics Chicago provides for its athletes. We look forward to the public enjoying this collection as much as we have.

Additional Resources

- Peruse the finding aid for the Special Olympics records

- Read more about the founding of the Special Olympics

- Watch Museum president Gary T. Johnson’s oral history interview of Justice Anne M. Burke

Liliana Macias is a graduate student in Latin American and Latino Studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She has been a gallery engagement associate in Race: Are We So Different? since January and reflects on her experience in this blog post.

I have been working in Race for five months and by now if I close my eyes I can clearly see the visuals in the exhibition. If I cover my ears and close my eyes I can see the scholars in the videos and recite what they are saying. Despite my familiarity with the exhibition, every day I’m here feels like I’m stepping into it for the very first time. By now I have come to see it through the eyes of the groups and individuals who walk through its entrance. When I do tours, I encourage participants to contribute whatever experiential knowledge they have on the subject because I understand that we live with our race and, despite it being a fictional concept, our lives are marked by it.

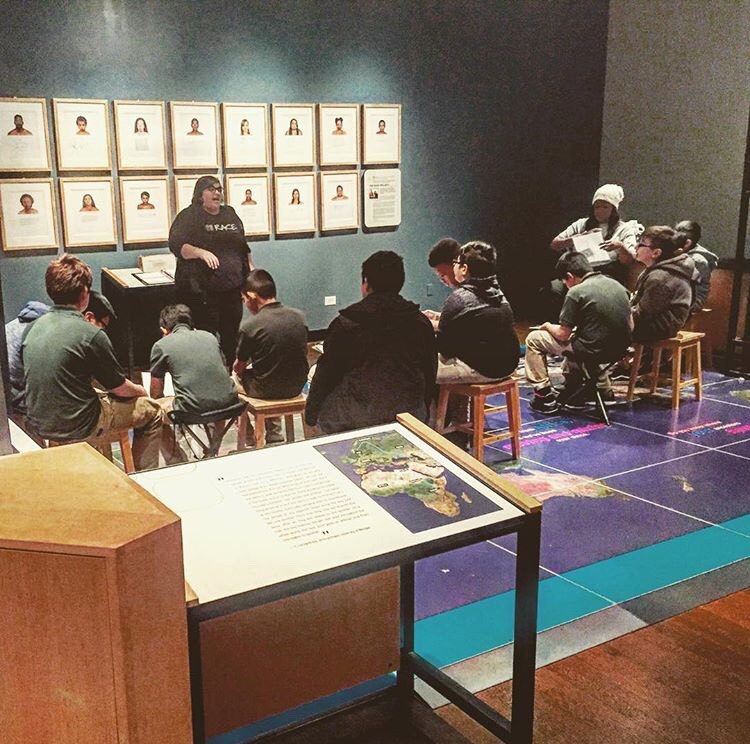

Liliana in the Race gallery. All photographs by CHM staff

When visitors connect with Race on a personal level and share their stories with me, I’m extremely humbled. Those stories contribute to the way I have come to understand race in the United States. As my knowledge expands on the subject, I improve on how I can engage with visitors. And even in those moments when tensions are high and a visitor rejects the social reality of what people of color experience, my prior interactions in the exhibition give me the knowledge I need to navigate those tense conversations. Even though the tension of those conversations can leave me feeling weary, I need only to conjure the precious shared stories of previous visitors and that weariness dissipates. I can feel the tension melt away when I think of the refugee children who have shared with me about their arduous journey to the US. I can feel it lessen when I hear young black children proudly assert that Black Lives Matter. I can feel the tension ease when I remember the elderly black couple who talked to me for an hour about their experiences during the Jim Crow era. I can feel it trickle away when I remember the young Mexican boy who asked me if he could share something with me in Spanish and was elated to know that I spoke Spanish like him, grew up in the same neighborhood as him, and was Mexican just like him.

A school group listens as Liliana talks about Kip Fulbeck’s The Hapa Project.

At the end of the day, my job as a gallery engagement associate at the Chicago History Museum is to honor those shared experiences by encouraging visitors to think critically about race in the hopes that they understand the urgency of abolishing the power structures that negatively impact our lives.

As part of Monday Night Nitrates, our weekly photograph series, CHM collections staff is blogging about the process of digitizing approximately 35,000 nitrate negatives, a project funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services. In this post, CHM senior archivist Dana Lamparello writes about making the images discoverable for research.

In many ways, the cataloging step for which I’ve been responsible in our IMLS-funded nitrate preservation workflow bridges the gap between physical and digital, i.e., between the physical nitrate negatives and the digital images and metadata that you’ve been reading about. The ultimate goal of this project is to limit access to the physical nitrate negatives (preservation) while still allowing the negatives to be discoverable for research (access), and it all comes together at this point in the process.

Six of the forty-six boxes of flexible nitrate negatives from the Charles R. Childs collection waiting to be scanned. Photograph by CHM staff

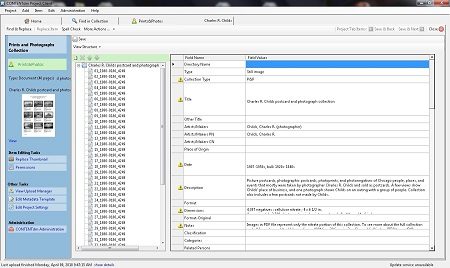

The back end of our ContentDM portal where data and files are added and edited.

First, it’s important to remember that each distinct group of nitrate negatives is considered an archival collection or part of a collection—in some cases, a much bigger collection than what the nitrate portion represents. For example, the Charles R. Childs collection totals nearly ten thousand images, but only about 45 percent of those are nitrate negatives, where the remainder is comprised of postcards, photographic prints, and glass negatives. Certainly all are formats with unique preservation needs but none as pressing as cellulose nitrate. It is important to tie these digitized nitrate images to the greater collection because without it, all context for the images will be lost. The John Walley collection’s nitrates, for example, exclusively document his 1937 Federal Art Project assignment to photograph life and industry in Alaska. The greater Walley collection more comprehensively documents the career of a Chicago-based designer, artist, and professor from 1937 to 1974. Thus, promoting discoverability of the nitrate negatives requires that they remain in context with the rest of the collection for complete understanding.

Childs’s work documented Chicago and the surrounding suburbs in the first half of the twentieth century, such as this image of Wacker Drive, c. 1925. CHM, ICHi-095740

In this photograph, Walley captured a worker unloading fish onto a boat, c. 1937. CHM, ICHi-094214

Like the Walley collection, most of the nitrates I encountered already correspond to a record in our library online catalog ARCHIE, which is the main access point and database to search all of our research collection holdings, including our photographic archival collections. ARCHIE records include summaries of each collection and with larger collections like Walley’s, a finding aid is available. Unlike the ARCHIE record, the finding aid provides more detailed information about the collection, mainly an inventory of each box or folder and details about what they contain. In addition to updating the information in ARCHIE records and finding aids to reflect the work completed for this project, including edits to the collection descriptions and adding data about the IMLS grant, restriction notes about access to the physical negatives, and new freezer storage locations, I also added a link to a separate inventory—one that details the nitrates. This visual inventory, as we call it, is simply a PDF with thumbnail-sized images of each digitized nitrate negative and very minimal metadata, including description, date, and copyright status evaluated by our Rights and Reproductions manager and utilizing standard rights statements from RightsStatements.org.

The collection-level ARCHIE record with links to the finding aid and nitrate PDF for the Charles R. Childs collection.

Researchers can quickly scan the PDF to search the collection.

The PDF is a means of quickly glancing through these images. Should you need to see a higher resolution image for your research, it is available upon request, but providing this quick view of the images allows you to see them in context with the rest of the collection, especially when the rest of the collection isn’t digitized.

PRIMARY SOURCE TYPE: PHOTOGRAPHS

The Remembering Dr. King: 1929–1968 exhibition invites students and teachers to walk through a winding gallery featuring of twenty-five photographs depicting key moments in Dr. King’s work and the civil rights movement, with a special focus on his time in Chicago. This classroom resource allows you to bring a portion of the experience into your classroom. It contains suggested activities, photograph analysis worksheets, as well as two timelines developed for the exhibition, one of Dr. King’s life and work, the other of national events that were part of the civil rights movement.

Remembering Dr. King – Classroom Resources

The photograph packet contains eight photographs from the exhibition to use in classroom instruction. The first page of the packet contains thumbnail images, captions, and the CHM reference number. Following that, photographs are printed on numbered, full-size pages, with the CHM reference number.

Remembering Dr. King – Photograph Packet

DePaul University students Joseph Flynn, Jay Kietzman, Jessica Licklider, and Lily Zenger delve into the issues surrounding the Civil War monuments in the Chicago area. They were students of Peter T. Alter, the Museum’s historian and director of the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, as part of DePaul University’s public history program. Former CHM intern and DePaul public history concentrator Sydney O’Hare edited their work.

While many familiar with Chicago’s history can recognize Grant Park’s iconic bronze statue of Union army general John A. Logan, few are aware of another Civil War monument that sits less than ten miles away in one of Chicago’s South Side cemeteries. Located near South Chicago Avenue and East Seventy-First Street in Oak Woods Cemetery, the Confederate Mound is a forty-five-foot-tall monument honoring the thousands of Confederate prisoners of war who died at Camp Douglas. Located in what is now the Greater Grand Crossing community, the camp was in operation from the war’s beginning in 1861 until its end in 1865. Both monuments were built in the 1890s, each receiving widespread attention from thousands of visitors when they were first unveiled.

A massive crowd joins city officials in the unveiling of the Logan Statue in Lake Park, now Grant Park, July 22, 1897. Photograph by George E. Mellen, ICHi-023906

The Confederate Mound, Oak Woods Cemetery, 2017. Photograph by Joe Flynn

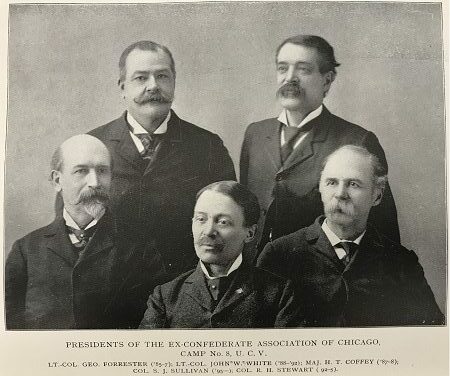

In June of 1891, members of the Ex-Confederate Association of Chicago met to appeal to donors they considered sympathizers of the Confederate dead in order to construct a monument in their honor. The Ex-Confederate Association originally intended to debut the statue during the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, but the project was not finished in time. The 1895 dedication ceremony drew a significant crowd, including a visit from President Grover Cleveland and his whole cabinet.

The presidents of the Ex-Confederate Association of Chicago from John C. Underwood, Report of proceedings incidental to the erection and dedication of the Confederate monument (Chicago: Johnston Print Co., 1896).

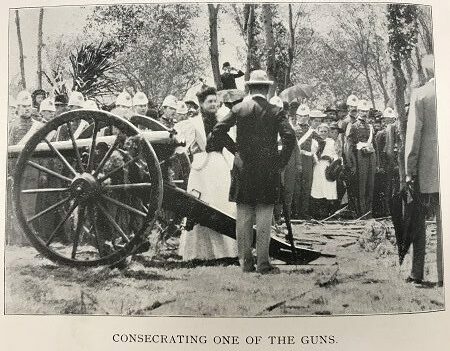

Soldiers gather around a man and woman preparing to “consecrate” the decorative cannons surrounding the memorial, 1895, from John C. Underwood, Report of proceedings.

Contemporary conversations about nationalism, historical understanding, and growing political tensions have made it especially important to reflect upon Confederate monuments and what they represent. Supporters of the monuments often claim that they represent southern heritage; however, a vast majority of the monuments were built from 1880 to 1910 in direct response to African American political gains in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As modern scholars have suggested, therefore, rather than preserving southern pride, these monuments romanticize an era built upon white supremacy.

A crowd forms around the Confederate Mound for a Memorial Day celebration, June 1915. Photograph by the Chicago Daily News, DN-0064548

Because the Confederate Mound in Oak Woods Cemetery was originally constructed to be somber rather than celebratory, it presents a unique set of circumstances and requires a different reflection. Its location on burial grounds and connection to Camp Douglas set it apart from the prominently displayed monuments typically found in southern town squares, government buildings, and public spaces. Yet the question still remains—how does a nation come to terms with its past when debates over historical morality and regional pride persist, especially in public spaces?

Additional Resources

- Read more about how the Civil War affected Chicago

- Get to know the Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation

On the fiftieth anniversary of Martin Luther King Jr.’s death, CHM director of curatorial affairs Joy L. Bivins reflects on his assassination.

On this date fifty years ago, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was fatally shot on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Today, around our city and throughout the nation, ceremonies of solemn remembrance will take place as we pause to reflect on the life and legacy of Dr. King, as well as what we all lost that day in 1968.

Only thirty-nine years old when he was murdered, King’s youth is often obscured by the international reputation he earned during his relatively short career. In 1955, at twenty-six and as a new father, he was asked to be a leader of the Montgomery bus boycott—a catalyzing event in the modern civil rights movement. In the next dozen years, he became the movement’s most visible leader, advocating tirelessly for the end of the nation’s violently oppressive racial caste system. His activism, rooted in an ethic of love and nonviolent action, stands in painful contrast with his violent murder.

King meets with President Lyndon B. Johnson at the White House, Washington, DC, 1963. Photograph by Yoichi Okamoto, ICHi-034763

King remained a committed civil rights activist but expanded his vision in the late 1960s. In 1967, he spoke out against the Vietnam War and launched the Poor People’s Campaign, a new movement aimed at economic and political redistribution for all Americans. In March and April 1968, King traveled to Memphis to support striking black sanitation workers. The night before his assassination, he powerfully addressed an overflow crowd at the Mason Temple assuring them that “We as a people will get to the promised land.” Less than twenty-four hours later, he was pronounced dead.

Disbelief, anger, and grief at King’s assassination yielded devastating reverberations in the United States as nearly one hundred cities experienced some sort of civil unrest. In Chicago, a city King frequently visited and even called home in 1966 as he attempted to shine light on northern racism, the reaction was swift and fierce. African American communities, particularly on the city’s West Side, were overwhelmed by burning and looting that lasted from Friday through Sunday. To reclaim order, thousands of members of the Illinois National Guard were called in, along with the full force of the Chicago police. By Monday morning, at least nine Chicagoans were dead, hundreds had been arrested, and more than one hundred buildings were decimated.

National Guardsman in front of buildings burned in the wake of King’s assassination, Chicago, 1968. Photograph by Declan Haun, ICHi-068946

City officials quickly memorialized King by renaming South Parkway, the boulevard running through the heart of Black Chicago from Twenty-Fifth Street to 115th Street, after the slain leader. And over the next several years, activists pushed for a national holiday in his honor. In 1983, Dr. King’s birthday was recognized as a federal holiday—one that many of us celebrate as a day of service and reflection. It is, however, as important, maybe more important, to commemorate the death of this prophetic voice for justice and equality. His words and actions continue to illuminate just how high the cost of working for freedom can be. Today, let’s not only contemplate what he accomplished during his short life, but the brilliance, the possibility that was taken from us all on that day in April.

Patrolling officers walk past a storefront memorial to Dr. King, Chicago, April 5, 1968. Photograph by Tom Kneebone, ICHi-003624

Join us in reflecting on Dr. King’s life in the exhibition Remembering Dr. King: 1929–1968, which covers on his civil rights work and focuses on his time in Chicago.

Additional Resource

CHM curatorial assistant Brittany Hutchinson reflects on her work for our newest exhibition, Remembering Dr. King: 1929–1968.

The entrance to Remembering Dr. King. Photograph by CHM staff

At the Chicago History Museum, we are honoring the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with an exhibition, Remembering Dr. King: 1929–1968. It includes objects and images that reflect his work nationally and locally and asks visitors to think how they are carrying his legacy today.

Dr. King often spoke of the inherent connection between all people despite the circumstances that attempt to separate us. The exhibition explores connections between Dr. King’s life and the events taking place in the world around him. Along the perimeter wall of the gallery, a timeline follows Dr. King’s historic rise to prominence, the height of his leadership in the civil rights movement, and finally his untimely death at the hands of a white supremacist. It becomes clear that at the height of his popularity, the world that once influenced Dr. King begins to change as it became influenced by him.

The large images are arranged in an intricate grid. Photograph by CHM staff

Suspended in the center of the gallery are images related to Dr. King’s activism in Chicago. Along with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), he left the South in 1965 and announced the Chicago Campaign, establishing the Chicago Freedom Movement in order to continue the fight against racism. Determined to challenge Chicago’s closed-housing market, Dr. King moved his family to the North Lawndale neighborhood to draw attention to the conditions that Chicago’s black citizens faced. Along with local activists, he participated in open-housing marches in white neighborhoods around the city. In every instance, activists were met with anger and violence. At one march, Dr. King was struck with a rock thrown by a counterprotester in the Marquette Park neighborhood.

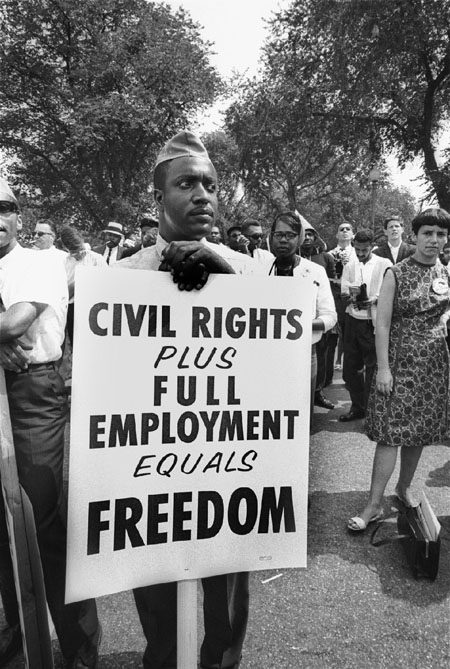

A protester holds a sign during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Washington, DC, August 28, 1963. Photograph by Declan Haun, ICHi-036879

The end of the Chicago Campaign in late summer 1966 signaled a shift in Dr. King’s focus as well the public’s opinion of him. In spring 1967, he delivered an antiwar sermon, “Beyond Vietnam,” at Riverside Church in New York City. That same year, he announced the Poor People’s Campaign, a plan to unite the nation toward economic equality and justice. Activists from multiple racial backgrounds pledged to join Dr. King in the fight to uplift the American working class through securing fair wages, full employment, and economic empowerment. The combination of an antiwar and anticapitalist platform hurt Dr. King’s already waning popularity.

Following news of Dr. King’s assassination, massive riots broke out in Chicago and several other US cities, April 1968. Photograph by Declan Haun, ICHi-062889

Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated by James Earl Ray at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. Response to his murder was swift and violent, and Chicago was especially impacted. The day after Dr. King’s assassination, uprisings erupted across the city. The National Guard was called in to patrol the city until order was restored on the following Monday.

Mourners gather at the funeral for Dr. King in Atlanta, April 9, 1968. Photograph by Declan Haun, ICHi-062906

Dr. King’s influence on American society continued on after his death. One week after his assassination, Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Federal Fair Housing act of 1968 into law. In November 1983, Ronald Regan signed the King Holiday Bill establishing that, beginning in 1986, every third Monday of January should be observed as a national holiday. Dr. King’s legacy lives on as each year we celebrate his life by asking ourselves how we can help to continue his fight against inequality and toward freedom.