Latest Posts

It’s National Deep Dish Pizza Day! Where will you be ordering from tonight?

Modern pizza is reputed to have started in Naples in 1889 when Raffaele Esposito created the “Pizza Margherita,” with tomato, mozzarella, and basil replicating the colors of the Italian flag, for King Umberto I and Queen Margherita of Italy. From there, pizza spread across the world. Some late-nineteenth-century Chicago bakeries served pizza, in sheets or in small rolls. Early Italian families served pizza on Taylor Street and the Near South Side.

Chicago-style pizza first appeared in fall 1943 with the opening of Pizzeria Uno. Many GIs had been introduced to pizza as they moved up the coast of Italy, and several Chicagoans anticipated that they would want more when they returned home. Restaurateur and bon vivant Ric Riccardo became partners with Ike Sewell, a liquor salesman, and Sewell’s wife, Florence, who had high-society connections in Chicago, in the new venture. Pizzeria Uno was located a few blocks from the well-known Riccardo’s on Wabash Avenue at Ohio Street. Lou Malnati, Riccardo’s associate manager, was brought over to help run the new establishment.

The Chicago style of pizza was marked by three characteristics: (1) enormous amounts of cheese and a thick, sweet pastry shell crust; (2) very high oven temperatures (600°F) while baking, with plentiful amounts of cornmeal sprinkled in the pan to help insulate the bread; and (3) very long cooking times (fifty to sixty minutes for a medium-sized pie). Such long cooking times allowed patrons time to consume many bottles of Chianti and Lambrusco while waiting.

Newspapers and visitors gave the new restaurant and its new pizza their enthusiastic support. Bolstered by the success of Uno, Sewell opened Pizzeria Due a few blocks away, and Chicago-style pizzerias spread throughout Chicago and the United States.

See more images of Chicagoans enjoying pizza.

Touring Chicago’s Culinary History

Trace the city’s evolution from meatpacking capital to foodie paradise. Our Google Arts & Culture exhibit Touring Chicago’s Culinary History features a selection of menus from our extensive historical collection. From the establishment of the first fine dining restaurant in 1835 to the recent contributions to world cuisine, learn about the origins of Chicago’s status as one of the top food cities of the world.

Left: Caray in the bleachers at the White Sox’s Comiskey Park, October 1, 1981. ST-80004240-0013, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; right: Caray greeting fans and Cubs baseball players and staff at Wrigley Field after recovering from a stroke, May 19, 1987. ST-50004111-0009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

As the weather warms up, many Chicagoans’ minds turn to baseball. Despite injuries, contract negotiations, and other issues, Sox and Cubs fans always have hope this time of year as a new season stretches out before them.

Harry Caray, longtime Sox and Cubs broadcaster, often spread this early season cheer. Whether handing out beer, taking a shower in the stands, trying to pronounce players’ names backwards, or broadcasting from the bleachers, he made watching and listening fun despite the score or the season’s prospects.

While he did call other professional and some college sports, Caray rose to fame as the St. Louis Cardinals’ broadcaster from 1945 to 1969. He arrived on Chicago’s South Side to announce Sox games in 1971. By 1976, famous Sox owner, Bill Veeck, had Caray singing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” during the seventh inning stretch at Comiskey Park.

With a change in ownership, Caray left the Sox and replaced Chicago baseball legend Jack Brickhouse starting with the Cubs’ 1982 season. Caray’s stardom grew on the North Side. With the Cubbies’ games on WGN-TV’s Superstation, fans across the country heard his renditions of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” from Wrigley Field. Over the years, he hosted numerous celebrities and notable figures in the Cubs’ broadcast booth, including President Ronald Reagan and then First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton. After more than five decades of broadcasting, he died in 1998.

Additional Resources

- Visit the “Wait ’til next year!” section of Chicago: Crossroads of America exhibition to learn more about the history of Chicago sports.

- See more images from Harry Caray’s storied career at CHM Images, which includes opening Harry Caray’s Bar and Restaurant and launching his Holy Cow Sodas soft drink line.

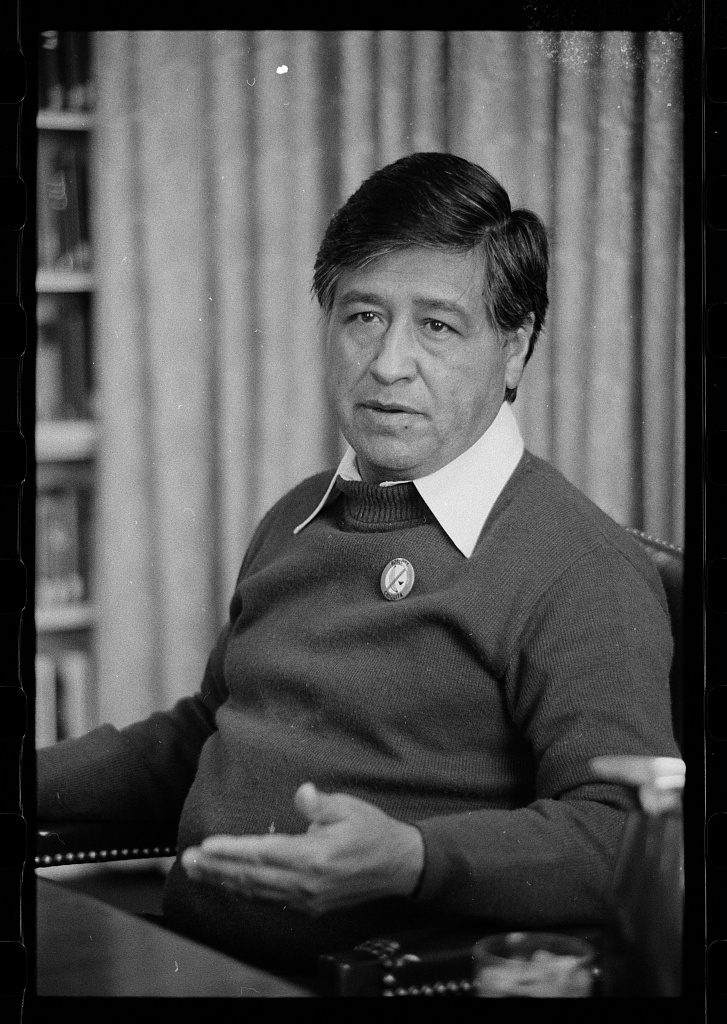

On March 31, 1927, Césario Estrada Chávez was born in Yuma, Arizona, to a Mexican American family. They moved to California in 1938 after his father was swindled out of some land. Both he and his family did field work all around California. Growing up, Chávez and his brother Richard attended thirty-seven different schools through eighth grade. Though he became an advocate for education later in life, he didn’t like school, where he was often forbidden to speak Spanish—the language he spoke at home.

Chávez joined the Navy in 1946 and served two years. In 1948, he married Helen Fabela, and they settled in Delano, California, and started their family. He became involved with the Community Service Organization (CSO) and helped laborers register to vote. Chávez became the CSO’s national director in 1959 but left the position in 1962 to cofound the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) labor union.

In the early 1960s, farmworkers called several strikes to demand higher pay and better working conditions from local grape growers. In 1966, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) joined forces with the NFWA to form the United Farm Workers (UFW). Together they pushed for contracts with powerful California growers—a nearly impossible feat—by staging a nationwide grape boycott. Boycotters stopped buying grapes, picketed stores that sold nonunion grapes, and spread the word about the cause.

Chávez was instrumental in organizing the boycott, which led to others. Each time, the UFW continued to raise awareness about the working conditions of farmworkers, stressing the dignity of the work and the worker, and connecting farmworkers’ rights to civil and human rights issues. Chavez and other UFW leaders came to Chicago regularly to seek support for their actions, especially from local labor leaders. In 1985, Chávez visited the city to organize boycotts against Jewel stores for selling lettuce from a producer that was hostile to farmworker unions.

Though considered a controversial figure by some, Chávez became an icon for organized labor in the US, the Cesar E. Chávez Multicultural Academic Center in Chicago is named for him, and his birthday is a federal commemorative holiday recognized by nine US states. Learn more about Chávez and the UFW’s grape boycott on our Facing Freedom in America website.

Image: Interview with Cesar Chávez. 4/20/1979. Marion S. Trikosko, photographer. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report magazine photograph collection, LC-U9-37548-32

Studs Terkel Radio Archive

In his forty-five years on WFMT radio, Studs Terkel talked to the twentieth century’s most interesting people. In 1967, he sat down with Chávez to discuss the United Farm Workers effort to gain rights for farm laborers and his childhood that led him to become a labor rights activist.

“In all of the major struggles and minor struggles of the organized labor movement, even though history doesn’t always record it, women were there.” —Reverend Addie L. Wyatt

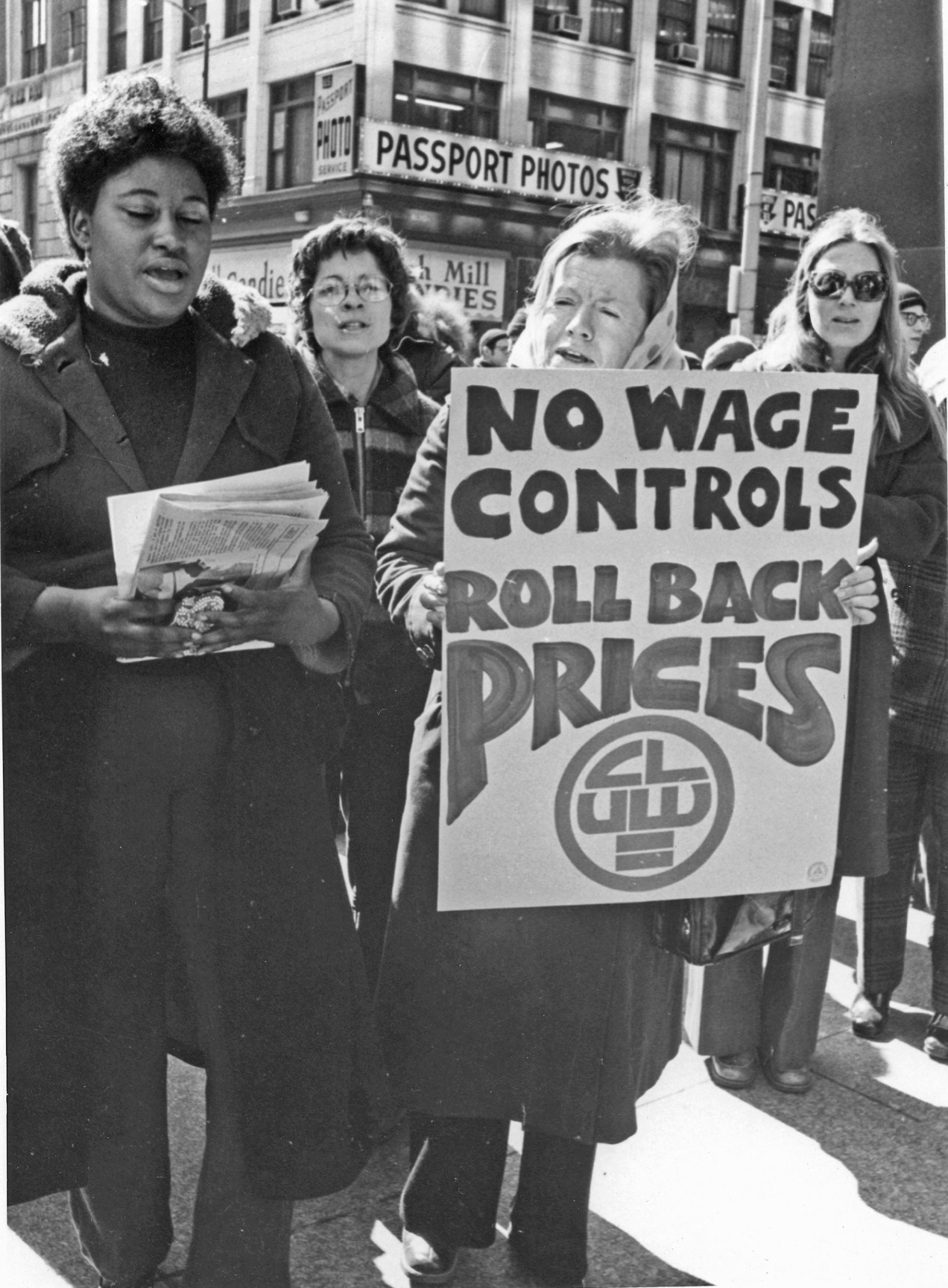

Group of Coalition of Labor Union Women picketers in Chicago, c. 1975. CHM, ICHi-039912

On this day in 1974, the Coalition of Labor Union Women (CLUW) was formed at a founding conference held in Chicago and attended by more than 3,000 union women from around the country. The CLUW sought to organize and empower women by increasing their participation in unions, advance workplace fairness, promote affirmative action, and ensure working women’s voices in the political process.

The formation of the CLUW came about in June 1973 at a meeting of women union leaders, including Olga Madar (the CLUW’s first president) of the United Auto Workers and Chicago’s Addie L. Wyatt of the United Food and Commercial Workers. They had gathered to discuss forming a new group within the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) that specifically gave women a voice in economic issues.

Wyatt battled intersecting gender, racial, and economic injustices throughout her life. Born in Mississippi on March 8, 1924, she and her family moved to Chicago in 1930. She started working as a meatpacker in 1941 and quickly became involved with the United Packinghouse Workers of America union. In the 1960s, she campaigned for Black voting rights in the South and fair housing in Chicago, serving on the action committee of the Chicago Freedom Movement.

Wyatt was also a founding member of the National Organization for Women and supported the Equal Rights Amendment. As a union leader, she fought racial and gender-based workplace discrimination. In 1976, she became international vice president of the United Food and Commercial Workers, making her the first African American woman to hold a leadership position in an international union.

Read more about women’s labor activists in our online experience, Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.

The Chicago History Museum is featuring a collection of many never-before seen works by world-renown photographer Vivian Maier in an upcoming exhibition, Vivian Maier: In Color, opening to the public May 8, 2021.

“The Chicago History Museum is committed to sharing Chicago stories, and Vivian Maier’s work represents her private contributions to the documentation and representation of culture found within city life,” said Charles E. Bethea, Andrew W. Mellon Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs. “Maier’s photography brings a glimpse of Chicago and its residents to life between the 1950s to the 1970s, allowing present day visitors the opportunity to reflect on the striking parallels it has to today’s society.”

Maier worked as a nanny to several Chicago families and took extensive photos, documenting intimate moments of the city and its people. Vivian Maier: In Color will illuminate Maier’s unique portfolio. While her focus of attention varied, she approached all of her work with unwavering confidence, revealing parallels, intersections and tensions.

Following her death in 2009, Maier’s prolific photographs previously discovered in her abandoned storage locker were first displayed for the public. Maier rose to posthumous international acclaim for her photography that expertly documented the people, landscapes, light, and development of New York, her hometown, and Chicago where she settled, with remarkable attention to detail. Maier’s work is now used widely in research and curriculum and has been celebrated in at least 42 exhibitions around the world, including one on display at the Chicago History Museum from 2012-2017, Vivian Maier’s Chicago.

To underscore her accomplished photography, Vivian Maier: In Color will feature more than 65 color images from the 1950s-1970s, most of which have never been seen, from art collectors Jeffrey Goldstein, John Maloof, and Ron Slattery. It is the first time the work in these three collections have been featured together in one exhibition. The exhibition will also include clips from film, made by Maier, and a series of sound bites and quotes featuring Maier’s voice.

“Vivian Maier’s photographs show moments of what looks to be a dynamic, multifaceted life in which she prioritized her passion for taking pictures,” said Frances Dorenbaum, curator of Vivian Maier: In Color. “Her dedication to photography is what makes her work so prolific today, and the Chicago History Museum is thrilled to share her voice with the public and celebrate a once unknown artist.”

The exhibition comes after the Chicago History Museum last year acquired nearly 1,800 Vivian Maier color slides, negatives and transparencies from Chicago-based artist and art collector Jeffrey Goldstein. The collection primarily depicts people and scenes in Chicago from the 1950s-1970s. The museum worked closely with Goldstein and Vivian Maier’s Estate to accept a donation of photographs and preserve them for public use. The acquisition gives the public access to many never-before-seen images on the Museum’s image portal.

The Chicago History Museum received a grant from The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation to process the Vivian Maier collection. The grant promotes long term preservation, collections access and interpretive digital output such as blog posts and an online exhibition.

To learn more about Vivian Maier: In Color and associated programs, please visit: www.chicagohistory.org/exhibition/vivian-maier-in-color/

The Chicago History Museum earlier this month broke ground on a multifaceted park beautification project. Named for long-time Chicago civic leaders and supporters of the Museum, Richard M. and Shirley H. Jaffee, the project features an accessible interpretive path around the Museum and includes renovations to the Museum’s public plaza. In cooperation with the Chicago Park District and community partners, the Museum seeks to make the 4.5 acres surrounding the building a more beautiful, educational, and welcoming space for all. The Jaffee History Trail will open to the public this fall.

“The Chicago History Museum is proud to continue sharing Chicago stories in an innovative way that encourages learning and critical thinking outside the museum’s doors, said John Russick, Senior Vice President for the Chicago History Museum. “We are honored to work with the Chicago Park District to make this interpretive path come to life, and we are incredibly thankful to our supporters, community partners, and neighborhood residents for their ongoing support and guidance during this important project.”

Each of the 8 stops on the walking path around the museum will explore aspects of Chicago’s personality, highlighting the city’s resilience and complexity. The Jaffee History Trail will serve as a space for continued education outside the museum, incorporating features such as the “Fire Blob”, a rarely seen and massive relic from the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 and the Couch Tomb, a reminder that the area was once a city cemetery.

“Enhancing park spaces for Chicagoans to enjoy and learn something new is the epitome of what the Chicago Park District seeks to support,” said Michael Kelly, Chicago Park District General Superintendent & CEO. “We are honored to work with the Chicago History Museum on the Jaffee History Trail project and eager to welcome the public to the space.

This project also includes necessary renovations to CHM’s underground collection storage facility, which sits directly below the plaza on the east side of the museum. The facility houses 23,000 linear feet of archives and manuscripts. Renovations will upgrade the structural integrity of the space and modernize the interior, so collection items are well-preserved and accessible for years to come.

Additional elements of the trail will include a garden featuring native plants, a collection of weathervanes designed in collaboration with the Chicago Park District’s 15 cultural centers and local artist Bernard Williams, and an open pedestal for visitors to consider what leadership means and what they stand for. The landscaping plan includes nearly 150 new trees and beds of native plants, which will attract birds and other pollinators.

As work continues on the Jaffee History Trail project, CHM invites members of the community to an upcoming virtual town hall to learn more about the project on April 13, 2021 at 5:30 p.m. via Zoom.

For more information on the Jaffee History Trail, FAQ’s, and a project timeline, please visit: www.chicagohistory.org/history-trail/

St. Patrick’s Day in Chicago is a renowned event rooted in cherished traditions. With not one but two St. Patrick’s Day parades, dyeing the Chicago River, and enjoying a green beer or two, Chicagoans know how to celebrate this beloved holiday.

While our celebrations will likely look different this year, we’re not missing the chance to honor the rich history behind one of our city’s favorite holidays. Tune in to WTTW Chicago tonight at 8:00 p.m. for “Labor of Love: A St. Patrick’s Day Special,” featuring fascinating insight on the history of Chicago’s Irish communities from Peter T. Alter, CHM’s chief historian and director of the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History. The WTTW original documentary reveals how the Chicago Journeymen Plumbers Local 130, UA, became involved in organizing the city’s downtown St. Patrick’s Day parade, how the dyeing of the Chicago River became a global event, the process behind the crowning of the queen and the selection of the grand marshal, and what it means to be Irish. You won’t want to miss it!

The Chicago History Museum has received a $2.5 million grant from Lilly Endowment Inc. through its Religion and Cultural Institutions Initiative. The grant will support the museum in establishing a new permanent role, Curator of Religious Community History, and the Fellowship for Religious Collections, a program for early career archivists in religious history collections. The museum is one of 18 organizations from across the United States that received grants through this initiative.

“The Chicago History Museum is honored to receive this award from Lilly Endowment Inc. to deepen our mission of sharing Chicago stories,” said Gary T. Johnson, president of the Chicago History Museum. “It is imperative that we create a more balanced understanding around religion and its significant history in Chicago and the U.S. through exhibitions and public programs. We are thrilled to begin the search for our new position, Curator of Religious Community History, and open the Fellowship for Religious Collections opportunity.”

The Chicago History Museum has delved into religious faiths and communities in past exhibitions. They included Catholic Chicago, which brought to light nearly two centuries of Chicago’s rich Catholic history, and Shalom Chicago, which traced the history of Chicago’s Jewish community through personal stories and artifacts dating back to the 1840s. American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago, open now through May 2021, explores themes of journey, identity and faith from the perspectives of Muslim Chicagoans.

Lilly Endowment awarded grants totaling more than $43 million through the initiative. These grants will enable the organizations to develop exhibitions and education programs that fairly and accurately portray the role of religion in the U.S. and around the world. The initiative is designed to foster public understanding about religion and lift up the contributions that people of all faiths and diverse religious communities make to our greater civic well-being.

“Museums and cultural institutions are trusted organizations and play an important role in teaching the American public about the world around them,” said Christopher Coble, Lilly Endowment’s vice president for religion. “These organizations will use the grants to help visitors understand and appreciate the significant impact religion has had and continues to have on society in the United States and around the globe. Our hope is that these efforts will promote greater knowledge about and respect for people of diverse religious traditions.”

Lilly Endowment launched the Religion and Cultural Institutions Initiative in 2019 and awarded planning grants to organizations to help them explore how programming in religion could further their institutional missions. These grants will assist organizations in implementing projects that draw on their extensive collections and enhance and complement their current activities.

Women march down State Street for the first women’s liberation march since 1916, May 15, 1971. ST-20003470-0019, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM © Sun-Times Media, LLC. All rights reserved.

March 8 marks International Women’s Day, which recognizes the social, economic, cultural, and political achievements of women.

The first National Woman’s Day was organized by the Socialist Party of America and observed on February 28, 1909. The following year, at the second International Conference of Working Women in Copenhagen, Denmark, it was proposed that there be a celebration on the same day every year for women to advocate for their demands. International Women’s Day was honored for the first time on March 19, 1911, in Austria, Denmark, Germany, and Switzerland. By 1914, the day was agreed globally to be observed annually on March 8, which it has remained ever since.

The way the day has been recognized varies from country to country. In the early years, it was often a day for marches, where women protested for the right to vote, to hold public office, and for equitable working conditions and pay. In the US, the day has moved away from its origins within the labor movement and is often used to recognize women’s achievements. In Chicago, March 8 has been a day that numerous women’s organizations have hosted rallies, programs, and other celebrations.

Women’s activism has a rich history in the Chicago area. Chicago women have chosen to challenge unfair employment policies, structural racism, and a lack of political representation. Our online experience Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote offers a glimpse of recent and distant moments when Chicago-area women mobilized for change, part of a long history of activism and protest.

Studs Terkel Radio Archive

In his forty-five years on WFMT radio, Studs Terkel talked to the twentieth century’s most interesting people. His daily radio show featured many of the leading advocates of feminism and women’s rights and covered topics such as lesbianism, women and labor, the concept of witches, feminism and race, and many others.

Naomi Anderson, c. 1893, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-755b-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

On March 1, 1843, Naomi Bowman Talbert Anderson was born in Michigan City, Indiana, to Elijah and Guilly Ann Bowman. She was a writer, speaker, and advocate for women’s rights and racial equality. Her mother encouraged her education, and at twelve years old her poetry caught the attention of the mostly white community and she was invited to attend the previously all-white school. At age twenty, she married barber William Talbert, and they moved to Chicago.

In Chicago, Bowman Talbert became involved in the growing women’s movement as well as the temperance movement, which promoted abstaining from alcohol consumption. In 1869, Bowman Talbert spoke at Chicago women’s suffrage convention and urged attendees to support voting rights regardless of race or sex. However, she wasn’t always credited for her work. Suffragists Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony publicized her 1869 speech in their newspaper, The Revolution, but identified her only as “a colored woman.”

After her husband died in 1877, Bowman Talbert had to support her family, first as a hairdresser and then as a teacher. She married Lewis Anderson in 1881, and they moved to Wichita, Kansas, where she continued her activist work. In Wichita, she founded an orphanage for Black children who were excluded from the whites-only children’s home. In the 1890s, she campaigned for suffrage, calling for “justice and . . . a voice in making the law” for women.

Learn more about Naomi Bowman Talbert Anderson and other early suffrage activists in our online experience Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.