Latest Posts

A Tutorial on Using the National/Diamond Garment Cutter Systems

Would you believe me if I told you that drafting custom patterns for historical clothing could be as easy as playing connect-the-dots? And that hundreds of these patterns are already available for free?

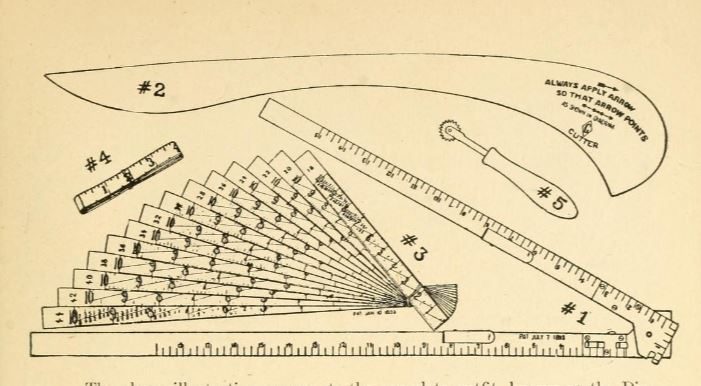

Welcome to the world of pattern drafting manuals of the late 19th century! These books were created as an alternative to paper patterns and promised their users greater flexibility in sizing, since the pieces were drafted individually according to the wearer’s measurements. The system depended upon the use of sets of rulers called “apportioning scales/rulers.”

Object #3 in this diagram is what the original apportioning rulers for this system looked like. Instruction Book by the Diamond Garment Cutter Correspondence School, 1903, pg. 3)

An apportioning ruler is a ruler where the numbers are not spaced according to inches or centimeters, but instead are placed further or closer together depending on how much you need to scale a pattern piece up or down from the base pattern to fit either your chest or waist measurement. When you copy the numbers on the diagram over to a new piece of paper using the correct apportioning ruler, the resulting pattern piece will fit whatever measurement you initially selected!

One popular system that uses apportioning rulers was invented in Chicago and I’ve found it to be a game-changer for sewing historically accurate costumes. Initially launched as the National Garment Cutter System in 1884, it was renamed the Diamond Garment Cutter System in the 1890s and also gained an accompanying periodical titled The Voice of Fashion, which offered subscribers more up-to-date patterns. Unlike many of their competitors, these books contained clothing patterns for men, women, and children.

| Year | Book | Link |

| 1884 | The National Garment Cutter by Goldsberry, Doran and Nelson | Scan available on Archive.org |

| 1888 | The National Garment Cutter Book of Diagrams by Goldsberry, Doran, and Nelson | Scan available on Archive.org |

| 1890 | The National Garment Cutter Book of Instructions and Diagrams by Goldsberry, Doran, and Nelson | Instruction book and Diagram Book available at the Abakanowicz Research Center |

| 1892 | Voice of Fashion [Summer] | Available at the Abakanowicz Research Center |

| 1895 | The Diamond Garment Cutter by Goldsberry, Doran, & Nelson | Scan available on Archive.org |

| 1897 | The Diamond Garment Cutter Book of Diagrams by W. H. Goldsberry | Available at the Abakanowicz Research Center (Contains three patterns designed for those with chest measurements between 38 and 45 inches) |

| 1897 | Voice of Fashion [Fall] | Scan available on Archive.org |

| 1897 | Voice of Fashion [Winter] | Scan available on Archive.org |

| 1900 | Voice of Fashion [Spring and Summer] | Available at the Abakanowicz Research Center |

| 1901 | Voice of Fashion [Summer and Fall] | Available at the Abakanowicz Research Center |

| 1903 | Instruction Book by the Diamond Garment Cutter Correspondence School | Available on Archive.org, this book has the clearest directions on using the system and adjusting patterns to fit different body types |

I’ve created several projects using these books and the apportioning rulers from the American Seamstress and have been impressed by how easy it is draft the pattern pieces. The best part is that there’s not a bit of math involved, all you must do is read numbers on a diagram and ruler! Keep reading for an explanation on how it’s done.

Ladies’ Street Costume (Diamond Garment Cutter Book of Diagrams, 1895, p. 52)

Ladies’ Bicycle Costume with Ferris Wheel Sleeves, (Diamond Garment Cutter, 1897, p. 82)

Ladies’ Visiting Costume (Diamond Garment Cutter Book of Diagrams, 1897, p. 17)

Tutorial

To create a pattern from these books that fits you, you will need:

- Gridded paper (wrapping paper with a grid on the back works well)

- Reproductions of the original apportioning rulers from Mrs. Depew

- A French curve

- A ruler

- A marker

- Scissors

Following the instructions on the pattern you select (“use scale corresponding with bust/waist/chest measure”), pick a ruler that matches the specified body measurement. For instance, if your waist measurement is 32, use the ruler that says “32” at the top.

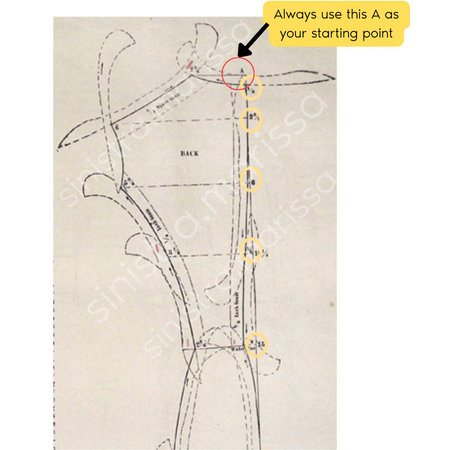

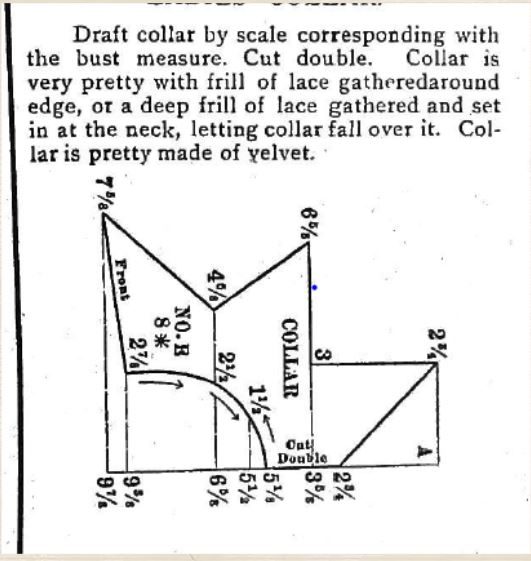

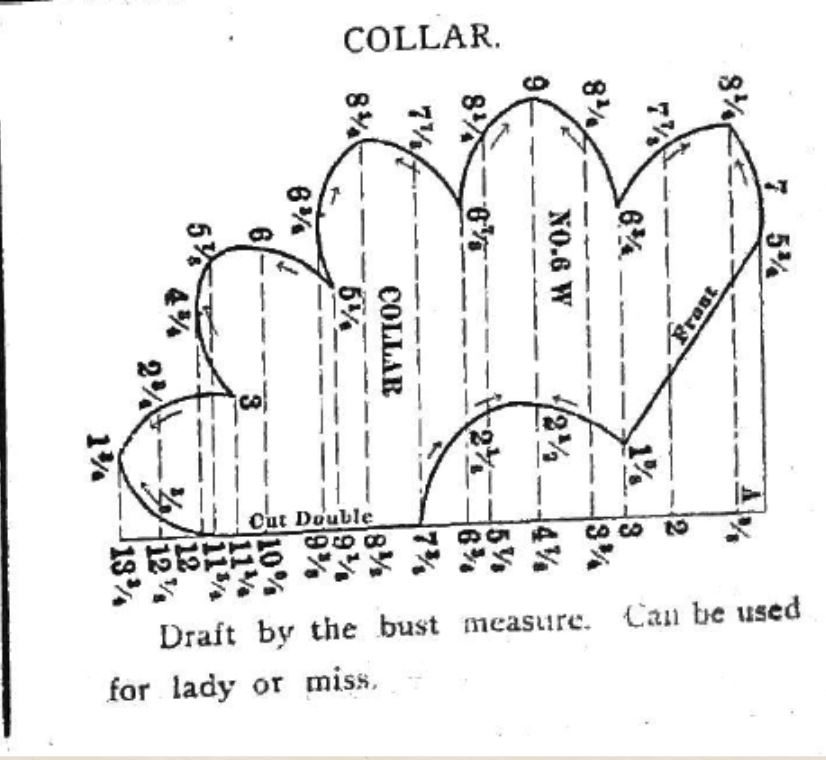

Step 1: Draw a large right angle on your grid paper, then use your selected ruler to make markings at the points corresponding to the numbers on the vertical axis of the diagram, starting where it says “A,” and then moving down (I find it helpful to label each point with the number it matches with in the diagram).

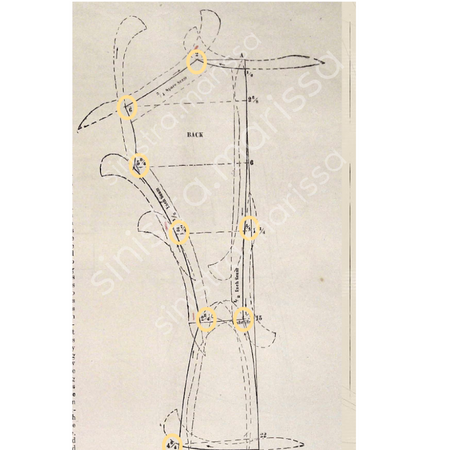

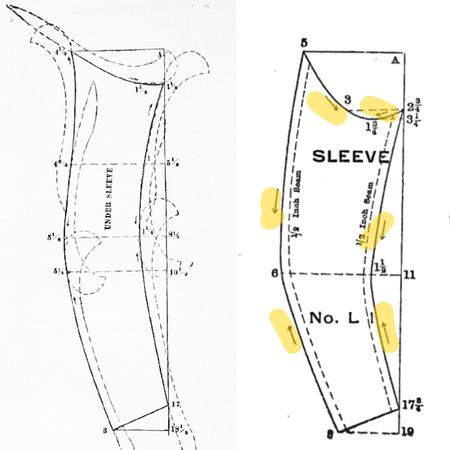

Step 2: Using the markings that you just made on the vertical axis as your starting points, repeat this process of measuring and marking the points on the horizontal axis. You should be left with something that looks like an unfinished connect-the-dots puzzle.

Step 3: Using your French curve and straight edge where necessary, connect the dots of your pattern to match the shape of the original diagram illustration. Your French curve’s largest side always points in the direction specified by the arrows on the original diagram (highlighted in right illustration). This will leave you with a pattern piece properly scaled up to your size, though you may still need to adjust it, so always do a mockup or a tissue fitting first.

Important: Wherever a pattern piece indicates “cut double” that means cut it out on the fold of the fabric! A seam allowance of roughly ¾ an inch is also included on these patterns, and they’ll note where this is not the case, usually at the shoulder seams.

Even if you’re familiar with how clothes are put together, creating a finished garment from these pattern pieces can be quite challenging because there are little to no directions of how the pieces need to be assembled. Studying pictures of extant garments can be helpful and I also recommend starting with something simple like these two detachable collars below, both taken from the 1897 Diamond Garment Cutter Book of Diagrams, page 19. Once you get the hang of it, you’ll have literally hundreds of free, historical patterns at your fingertips! Happy sewing!

Further Reading

- Remaking History: Sewing a Women’s Bicycle Costume from an 1897 Pattern

- PDF of patterns for the three Ladies’ Cycling Costumes

- Research Fashion History at the Abakanowicz Research Center using the Costume Research Files

- CHM Costume and Textiles Image Gallery

- Costume and Fashion Research Library Guide

- Follow my sewing projects on Instagram: @sinistra.marissa

May is Jewish American Heritage Month. In recognition, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman highlights materials from the Abakonowicz Research Center related to the National Council of Jewish Women.

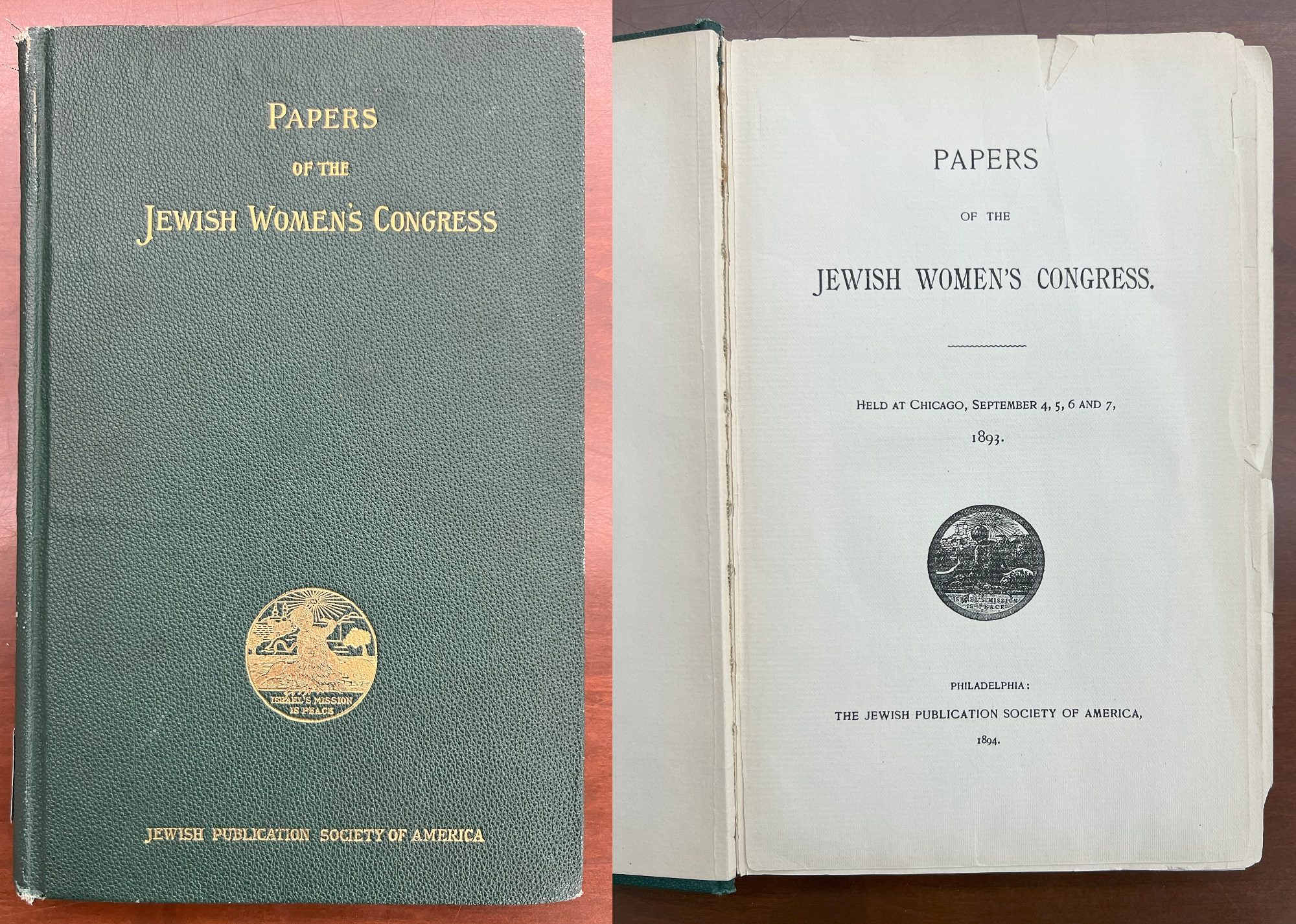

The National Council of Jewish Women is the result of a gathering of Jewish women that took place during the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE). In addition to the better-recognized national pavilions and Midway activities of that world’s fair, numerous ancillary activities were held, including the World’s Parliament of Religions. This gathering included representation from and congresses about religious representation, including denominationally specific committee gatherings. One such meeting, held by the Jewish Women’s Committee, became known as the Jewish Women’s Congress (JWC). The congress was held September 4–7, 1893, and saw participation by ninety-three delegates from twenty-nine cities. At its conclusion, the congress voted to establish the National Council of Jewish Women (NCJW), an organization still active today.

Papers of the Jewish Women’s Congress, 1894. E184.J5 J5 1893.

The NCJW was founded and chaired by Hannah Greenebaum Solomon (1858–1942), who was born to Sarah and Michael Greenebaum and raised in Chicago as one of ten children. She was active in both religious and social circles as a member of Temple Sinai synagogue and, along with her sister Henrietta, as the first Jewish members of the Chicago Women’s Club. As chair of the JWC, Solomon made the strategic move to shift the gathering of Jewish women from the WCE’s Women’s Building to the World’s Parliament of Religions, centering the philanthropic aims of the gathering and planning for its future initiatives.

Portrait of Hannah Greenebaum Solomon, c. 1915. CHM, ICHi-088576

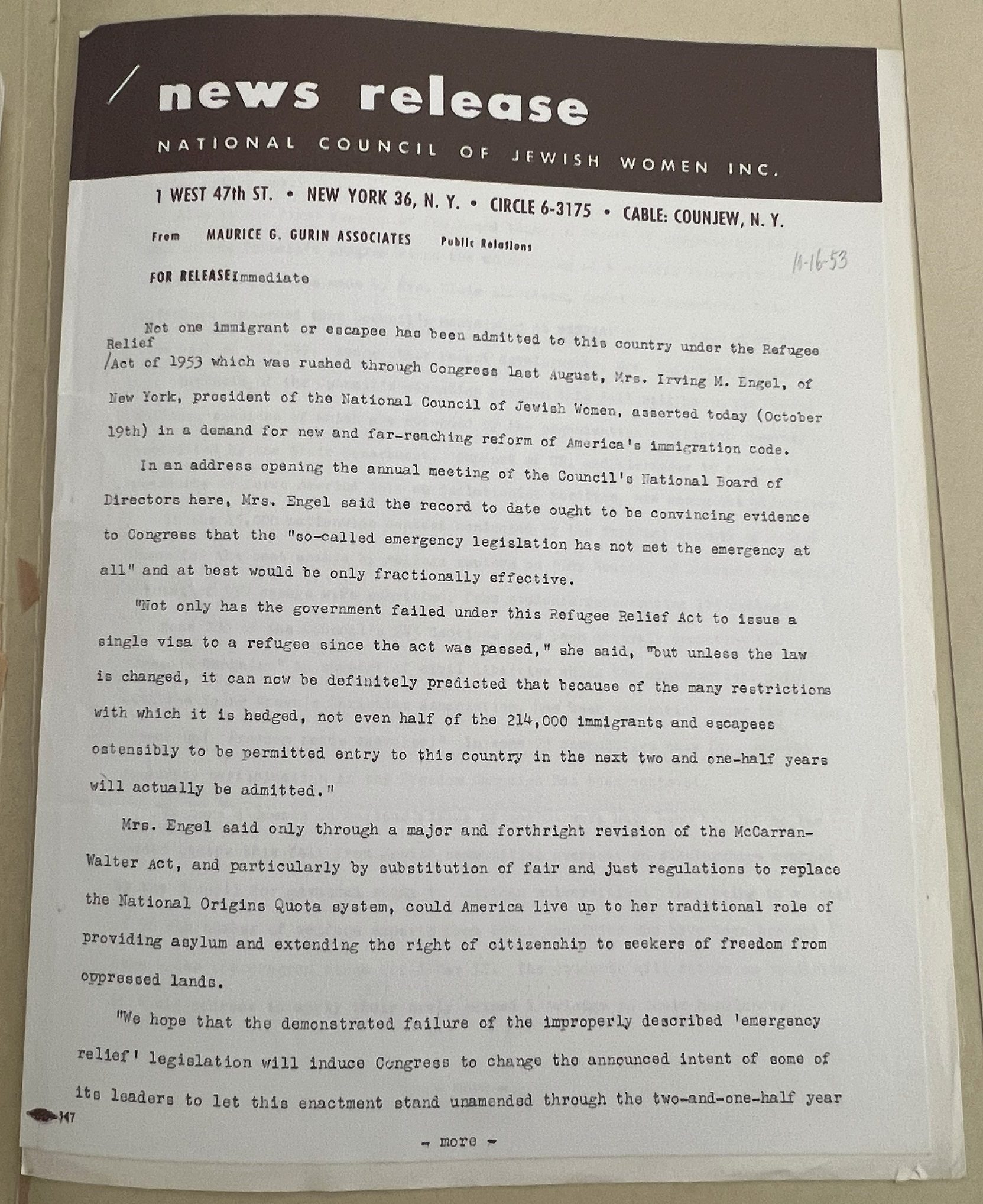

At its founding, the heart of the NCJW’s work was religious education for women and children. As the organization grew, it expanded its missional focus into broader philanthropic efforts, with a special emphasis of providing aid to immigrants. This included facilitating social services for young Jewish women through providing housing, vocational training, and other services to acculturate to American life.

Press release discussing immigration reform, dated October 16, 1953. Box 7, folder 2, “Council of Jewish Women; Community Service and Activities; Misc. Immigration”

Through Solomon’s connections, the NCJW remained allied with other organizations providing aid services, including Jane Addams and Hull-House. The NCJW’s membership grew quickly following its inaugural meeting, growing from its original ninety-three members in 1893 to more than 50,000 members by 1925.

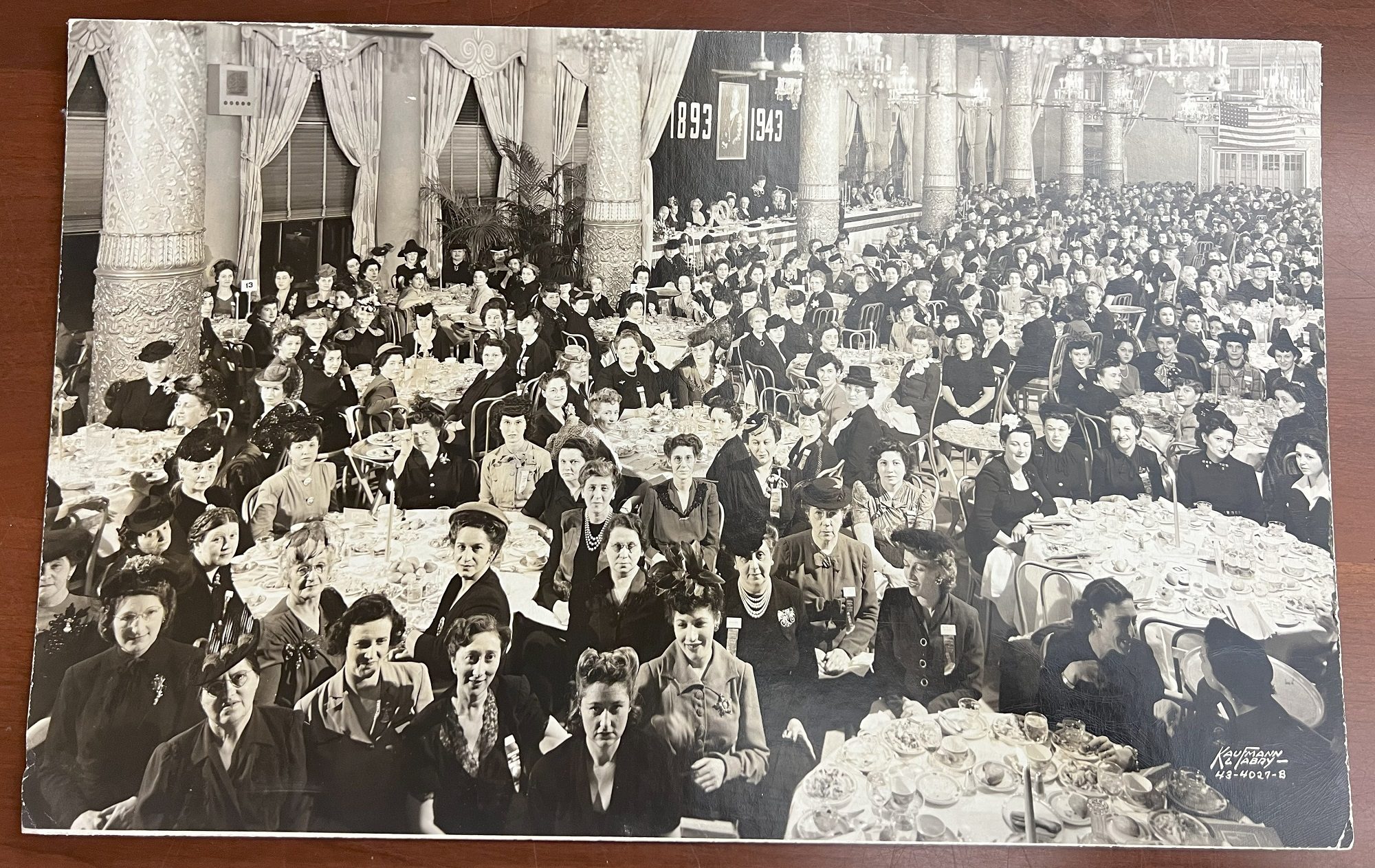

50th Anniversary Banquet of the National Council of Jewish Women, 1943.

In the early twentieth century, the NCJW expanded its advocacy and aid efforts as it fundraised for war relief during World War I, campaigned for passage of women’s suffrage in 1919, advocated for jobs during the Great Depression, and fought against racial discrimination. During World War II, it was active in a wide cross section of relief efforts, including working with displaced persons. The NCJW’s growth continued postwar and, by 1970, it boasted over 110,000 members. Its mission, too, continued to grow and shift as the organization saw the country’s philanthropic needs transform.

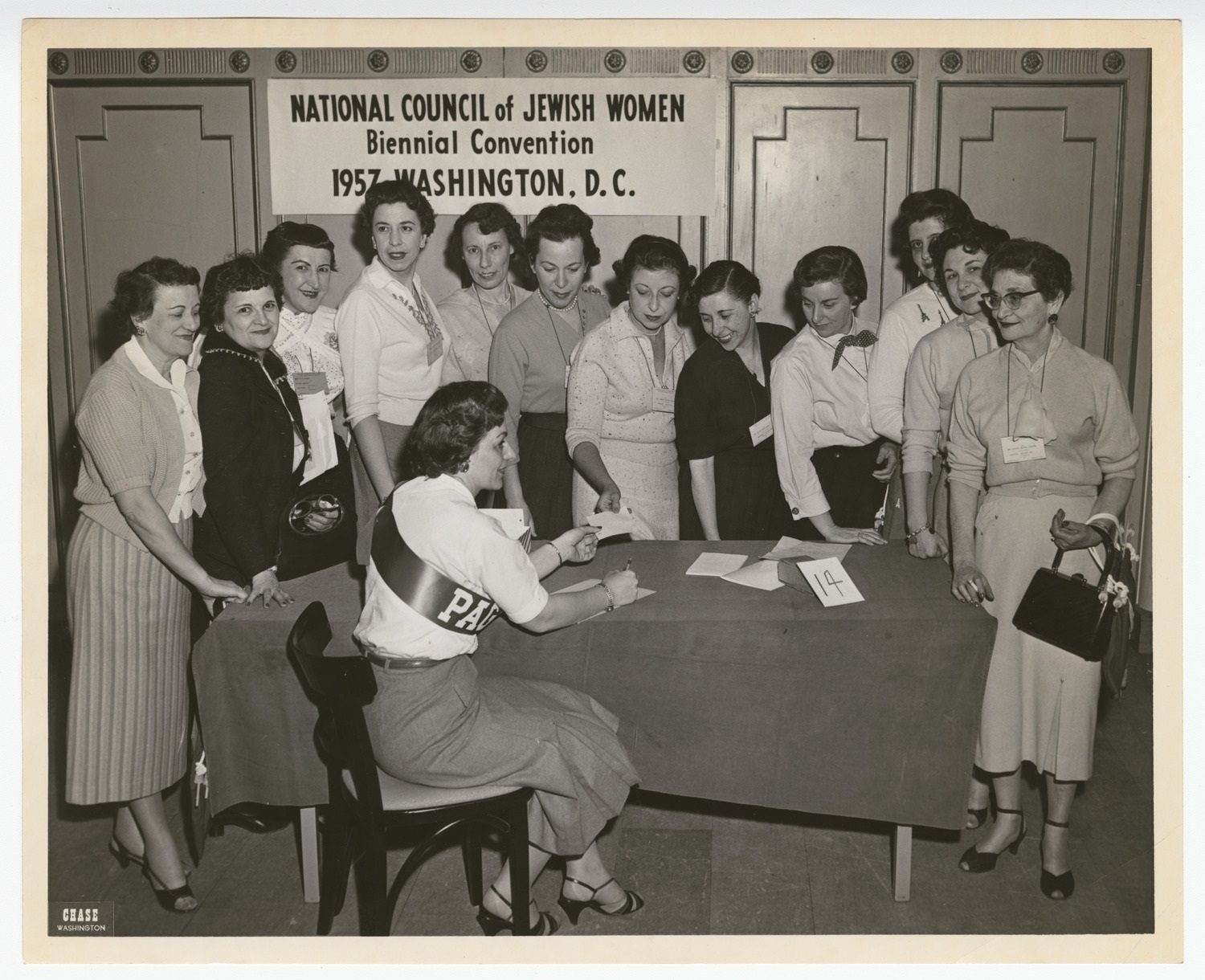

Women gathered around a table at the National Council of Jewish Women 1957 Biennial Convention in Washington, DC. CHM, ICHi-088573

Today, the legacy of the NCJW continues through its continued presence as a grassroots organization centered on advocacy and political activism with approximately 210,000 members who are active in all fifty states and internationally. Through a Jewish lens, the NCJW advocates for pluralistic human rights issues including reproductive rights, voters’ rights, and resources for refugees.

Lions in front of the Art Institute of Chicago crowned with flower wreaths in honor of the 75th anniversary of the National Council of Jewish Women, 1969. ST-30000413-0004 (top) and ST-30000412-0002 (bottom), Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Art Institute lions wreath ceremony by group from the National Council of Jewish Women, 111 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago, Illinois.

These efforts expand the original mission of the NCJW and speak to the legacy Hannah Solomon identified in 1893: “The influence of the Congress is . . . not to be measured by the size of its audiences, nor by the merits of its papers. Its chief result is that it brought together, from all parts of the country, East, West, and South, women interested in their religion . . . Its outcome is a National Organization, and its use was to prove to the world that Israel’s women, like women of other faiths, are interested in all that tends to bring men nearer together in every movement affecting the welfare of mankind.”

Additional Resources

- View the papers of the Jewish Women’s Congress at the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit

- See more images related to the National Council of Jewish Women

The coronation of George VI on May 12, 1937, was the first to be filmed, first to be broadcast on radio, and the first where “the colored press had fully accredited representatives at such an historic occasion.” In this blog post, take a look at archival materials that document and give insight into the historic assignment undertaken by two Black journalists for the Associated Negro Press.

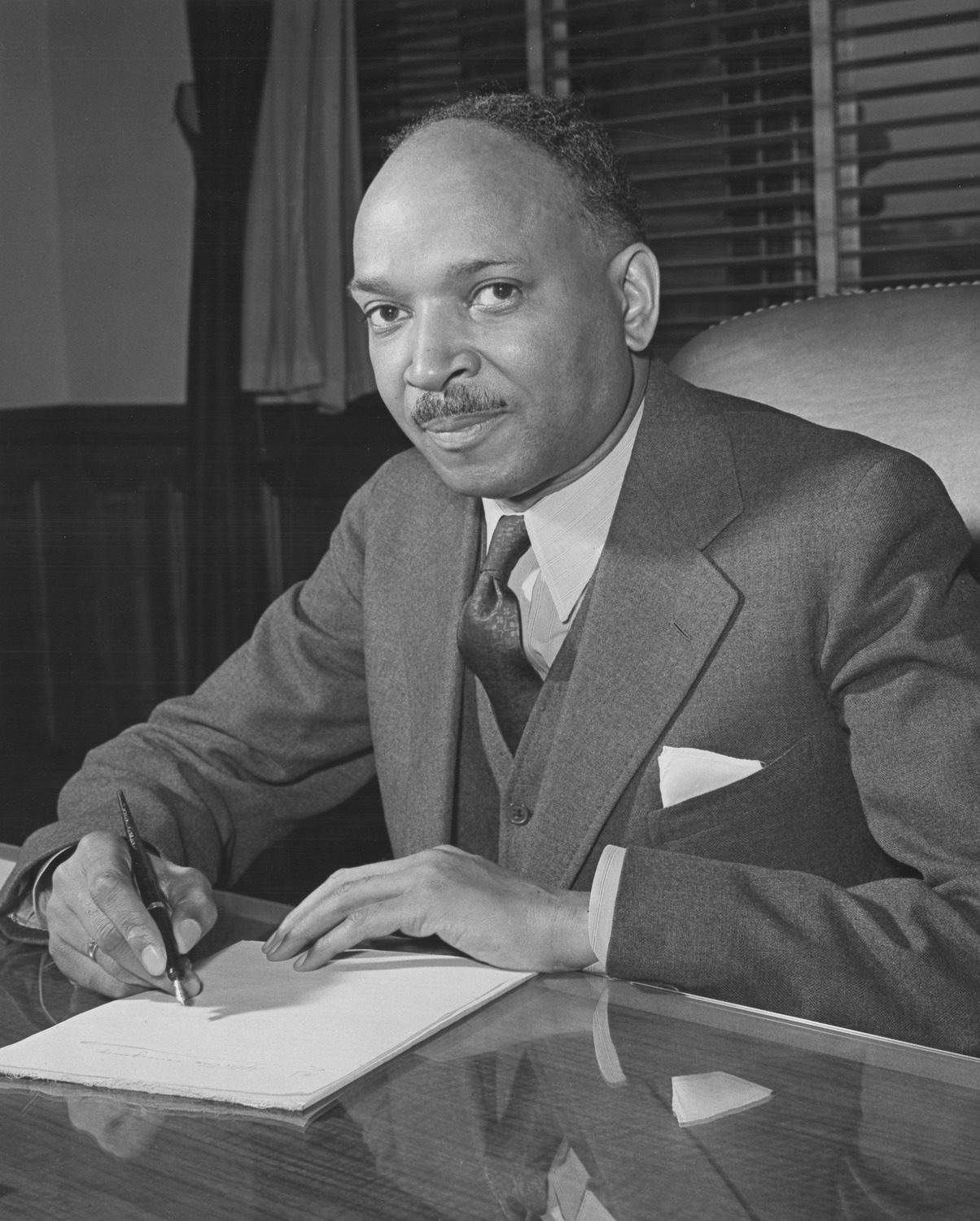

In 1919, a pivotal year for race relations in both Chicago and the United Kingdom, the Associated Negro Press (ANP) was established by Claude A. Barnett (1889–1967) in Chicago. With correspondents and stringers in all major centers of Black population, the ANP provided its member papers—the vast majority of Black newspapers—with a twice-weekly packet of national and international news that gave African American newspapers a critical, comprehensive coverage of personalities, institutions, and events relevant to the lives of Black Americans. Even as a relatively young news agency, the ANP sought to establish its voice on an international level. By 1945, it had a vast international network that expanded to Africa and London, bringing global awareness to important issues within Black communities through the lens of the Black American experience, including increased attention to civil rights concerns and the fight against persistent racism.

Undated photograph of Claude A. Barnett at a desk. CHM, ICHi-061826

In 1937, the ANP took strides toward expanding its international coverage through designating Fay M. Jackson (1902–1988) as foreign correspondent to Europe for six months with a central mission to cover the coronation of George VI. An ambitious and impressive force in journalism, Jackson’s precocious and straightforward writing style fore fronted her voice as a Black American journalist, a style that matched and amplified the reporting mission of the ANP.

Undated portrait of Fay M. Jackson. CHM, ICHi-022288

Born in Dallas, she moved to Los Angeles with her family at the age of 14. Jackson attended Polytechnic High School (’22), where she wrote for the school newspaper, followed by the University of Southern California (’27), where she studied journalism and philosophy. While still a college student, she wrote for the California Eagle and Pacific Defender, two LA-based Black newspapers, and was critical of USC’s institutional racism, as well as the hypocrisy of having such policies while affiliated with the Methodist Church. After graduating from USC, Jackson continued her journalistic pursuits: she started Flash magazine in 1928, served as the first African American female Hollywood correspondent accredited by the Motion Pictures Director’s Association, and was named the political editor of the California Eagle in 1931.

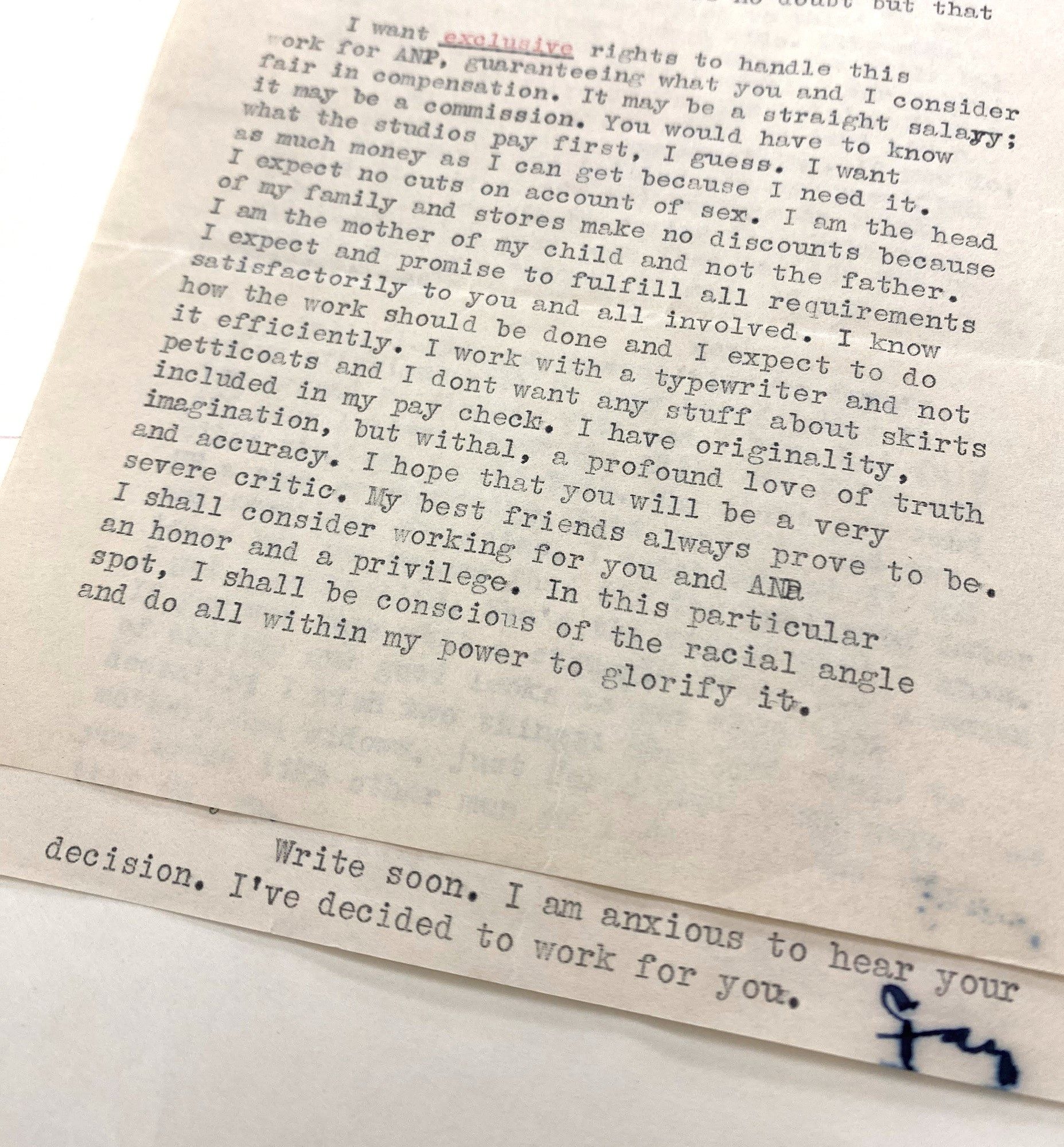

The earliest correspondence between Fay Jackson and Claude Barnett in the CHM Research Collections dates from 1933 with Jackson asserting her abilities and being forthright about her salary expectations. Barnett, impressed by her confidence, was not put off by such grand statements, and Jackson was appointed the Pacific Coast Representative for the ANP in November 1933.

Letter from Jackson to Barnett dated August 23, 1933, in which Jackson signs off with “I’ve decided to work for you,” even before she is officially hired. Claude A. Barnett papers, 1918–67, box 287, folder 1.

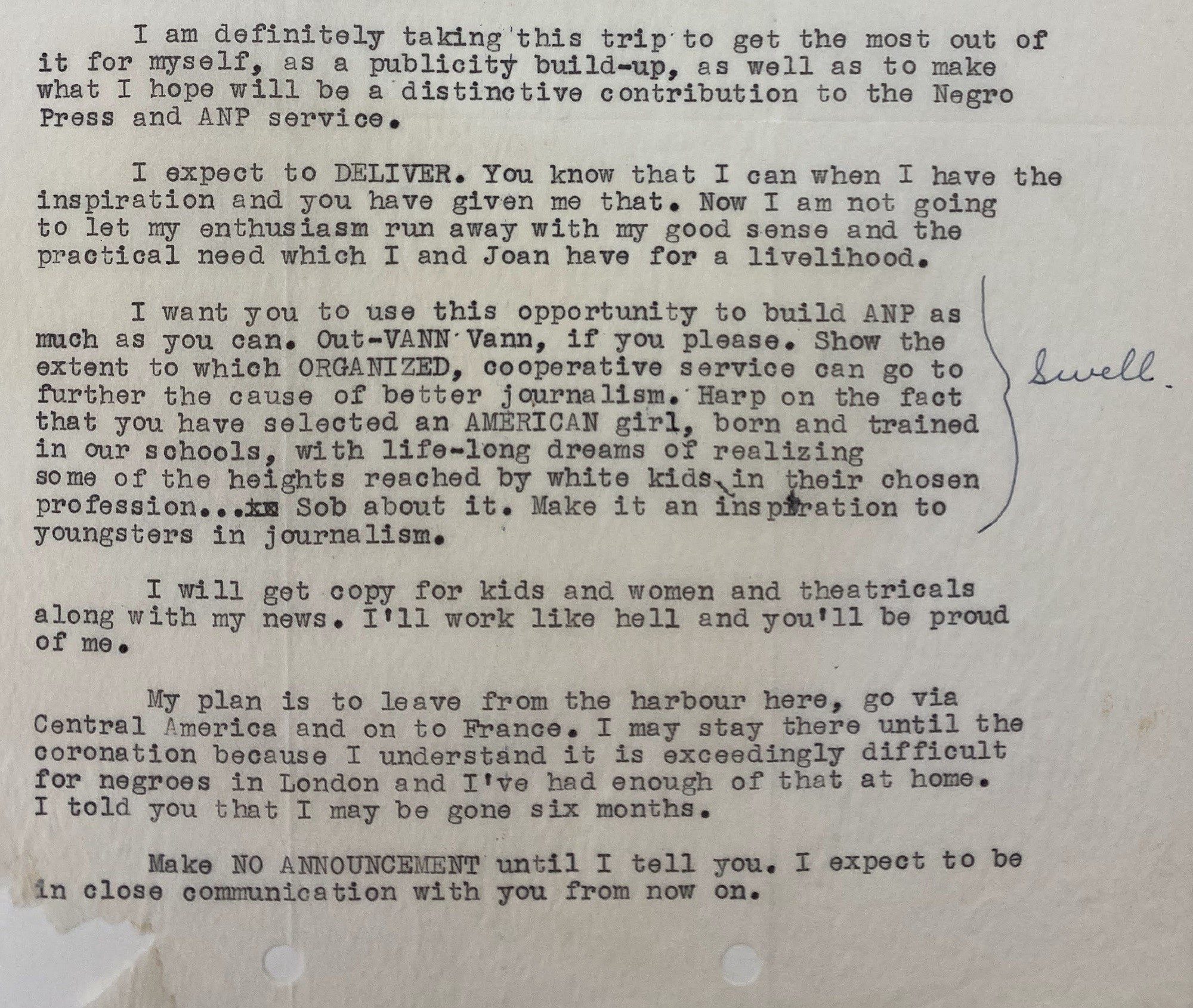

In October 1936, Barnett offered Jackson the opportunity to cover the coronation of George VI with Rudolph Dunbar (1899–1988), the ANP’s London correspondent. Jackson made her enthusiasm clear in her response: “I want you to use this opportunity to build ANP as much as you can . . . Show the extent to which ORGANIZED, cooperative service can go to further the cause of better journalism. Harp on the fact that you have selected an AMERICAN girl, born and trained in our schools, with life-long dreams of reaching some of the heights reached by white kids in their chosen profession . . . Make it an inspiration to youngsters in journalism.”

Excerpt of letter from Jackson to Barnett dated October 24, 1936, on which someone, most likely Barnett, approves of a paragraph with “Swell.” Note how Jackson describes London at the time. Claude A. Barnett papers, 1918–67, box 288, folder 1

Jackson’s coverage of the coronation came during a critical period for the United Kingdom, as the nation was transitioning from its status as the British Empire to a series of independent states known as the Commonwealth, precipitated by the 1931 Statute of Westminster just a few years earlier. Consequently, George VI’s reign would come during a decisive time both in terms of confronting the country’s status as a global power and in terms of national identity. Within just a few short years, the UK would find itself at war, and, within a decade, the process of decolonization would be accelerated as more former British colonies sought independence, including India and Pakistan in 1947.

Excerpt of correspondence from Jackson to Barnett, dated November 3, 1936.

Evidence of these underlying racial tensions painted Jackson’s perspective as she planned her itinerary. In a letter dated November 25, 1936, Jackson expressed a desire to stay longer in Paris than in London due to her hesitation about the treatment of Black people in Britain. After arrangements were made and accommodations were settled, Jackson left for Europe in early 1937 on an ocean liner from New York, traveling through continental Europe to report on the racial climate there.

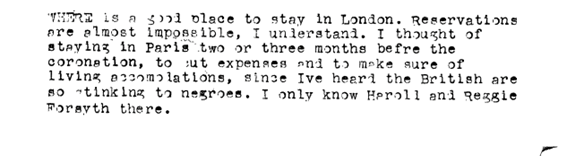

As the date of George VI’s coronation approached, arrangements were made for Jackson and Dunbar to attend. A telegram to ANP a few days before the event requested payment for seats.

Telegram from Jackson to the ANP, May 8, 1937. According to the Bank of England inflation calculator, £3 in 1937 would be £163.59 in February 2023, which would be $202.43 today. Claude A. Barnett papers, 1918–67, box 288, folder 1.

George VI ascended to the throne in January 1936, and his coronation was the first to which African royalty were invited. However, as Jackson would report, this did not mean an equal Black representation in all elements of coronation activities.

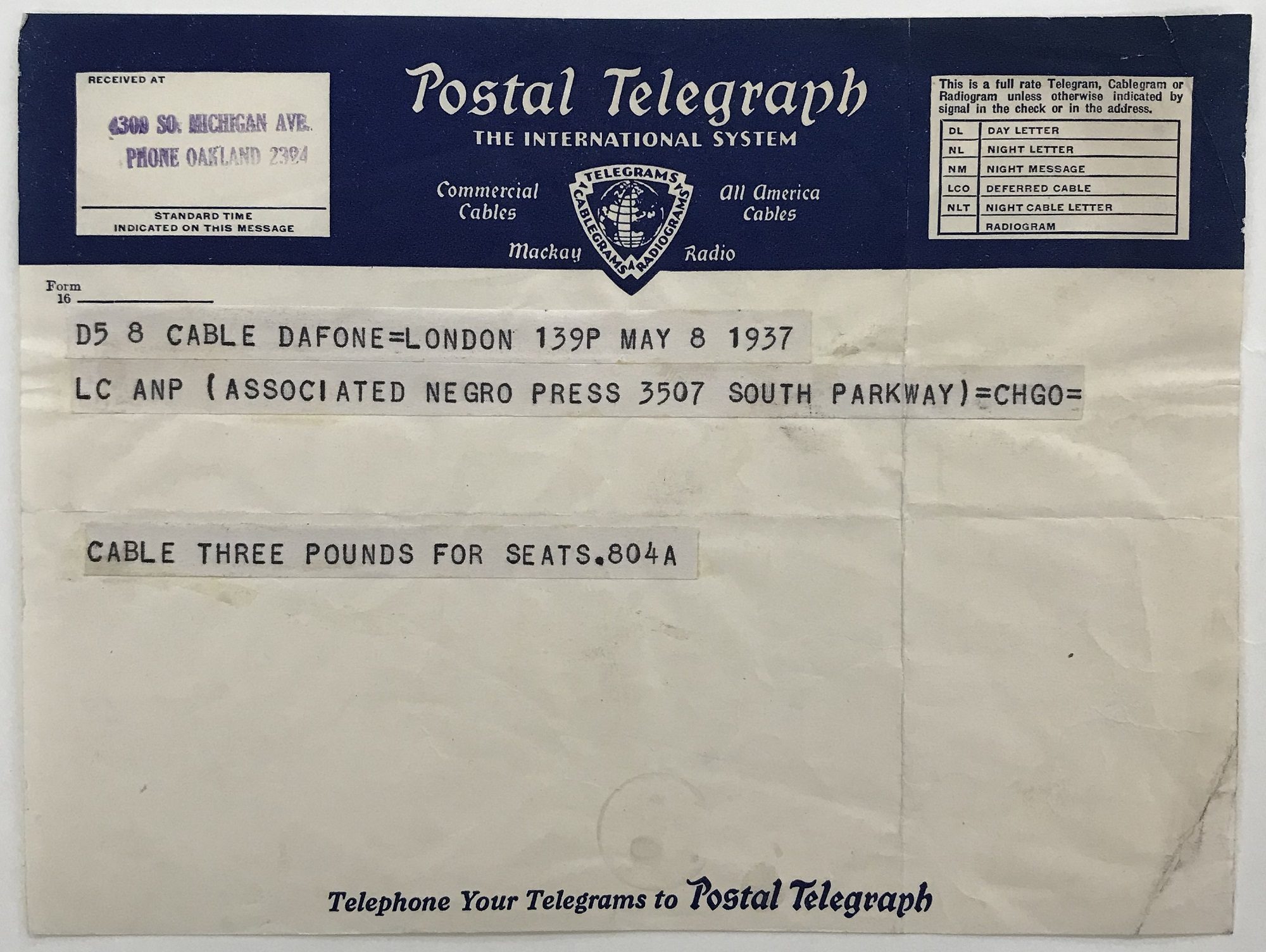

Photograph titled “The supreme moment of great solemnity: The crowning of the king by the Archbishop of Canterbury in Westminster Abbey.” The Illustrated London News, May 15, 1937, vol. 100, no. 2612. AP4.I3 FOLIO-B

The ceremony leaned into the traditional precedence set by George V’s 1911 coronation with subtle nods to the shifting status of the role of the monarch amidst the Commonwealth. Additionally, the media played a more prominent role than ever before in a coronation ceremony.

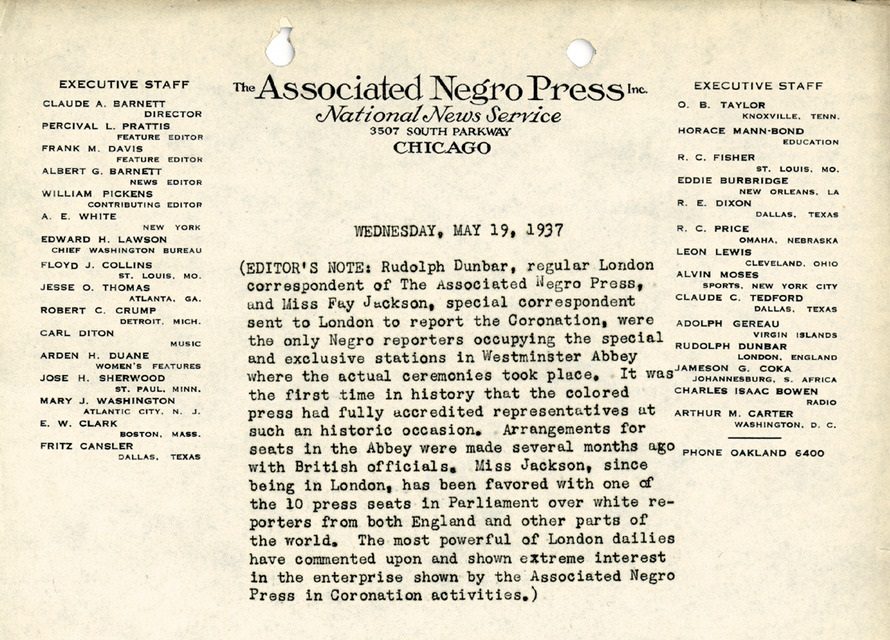

In Rudolph Dunbar’s dictum regarding the day of the coronation, his editor’s note states that he “and Miss Fay Jackson were the only Negro reporters occupying the special and exclusive stations in Westminster Abbey. It was the first time in history that the colored press had fully accredited representatives at such an historic occasion.”

The top half of a release regarding the coronation of King George VI, May 19, 1937. CHM, ICHi-068441

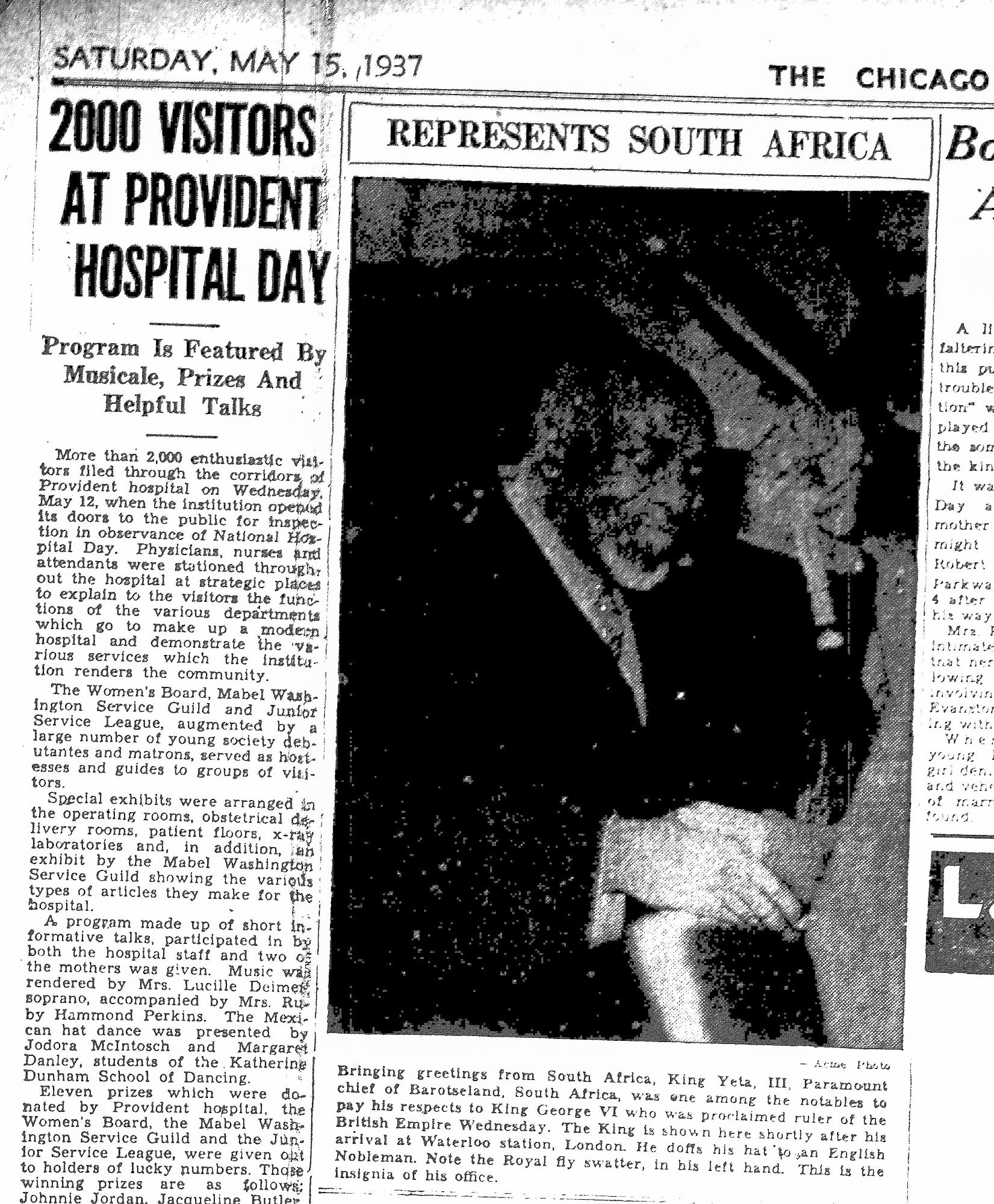

Jackson reported with a critical eye on not just what took place during but also obvious omissions to the coronation festivities. Her accounts recall how the African heads of state and Black dignitaries were treated unfairly. In one of her stories, she notes, “While 22 of the States and Mandated territories under His Majesty’s protection are black with a combined population of some 400 million, it may be clearly seen that nothing like the representation of blacks by black is here as, for instance, one notes among the Indians and other races . . . No Black Africans appear on the Royal Guest list. It will be recalled that the Chieftains were actually snubbed, originally, because the present King chose to follow the ‘precedent set down by his father, the late King George V.’ Two are here: Yeta III, Paramount Chief of Barotseland, and Ademola II, Alake of Abeokuta. They are included in the last as ‘distinguished visitors.’”

A photograph of King Yeta III, Paramount Chief of Barotseland, South Africa, arriving at Waterloo Station in London. He carries a fly swatter, the insignia of his office. Chicago Defender, Saturday, May 15, 1937, city edition.

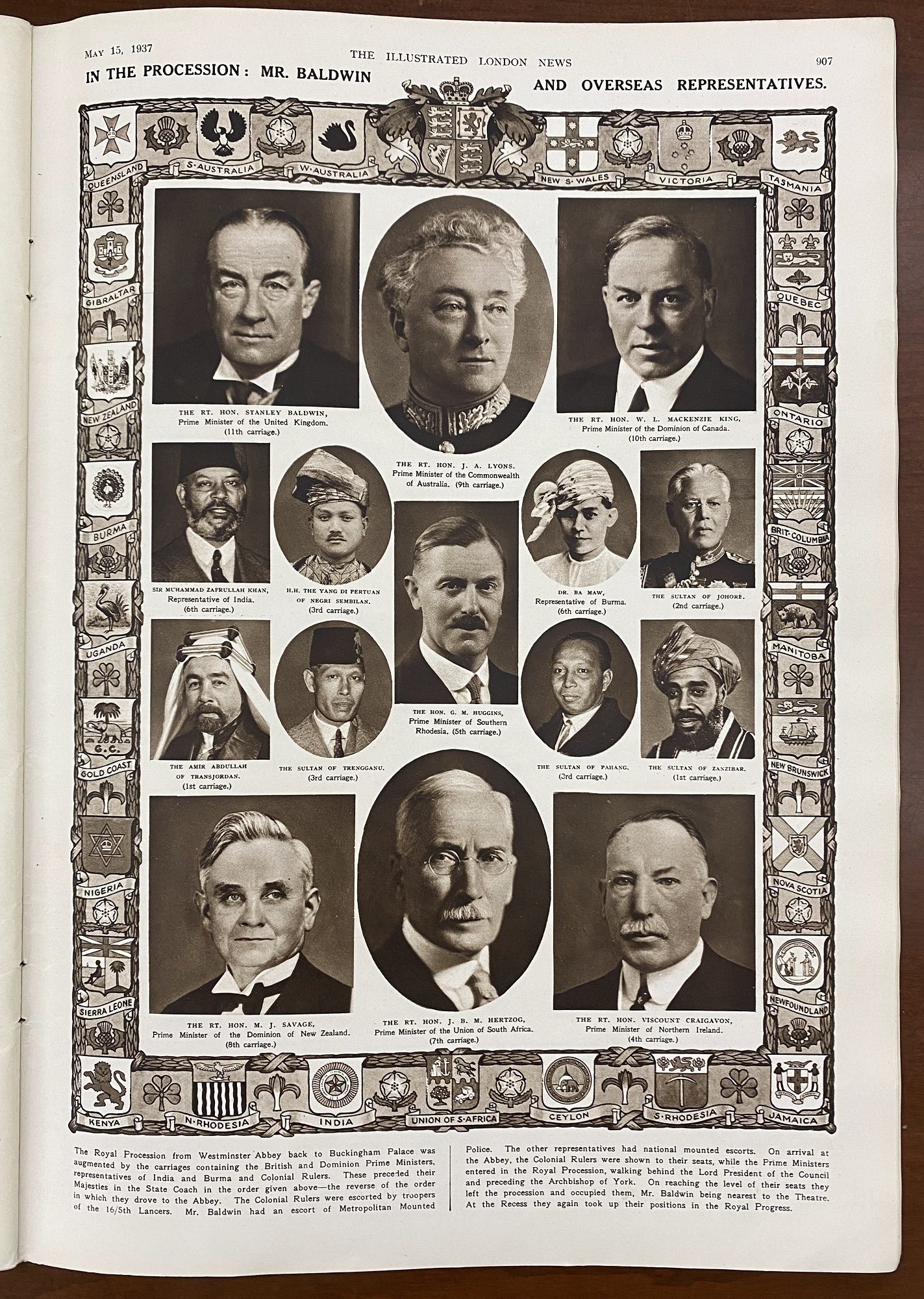

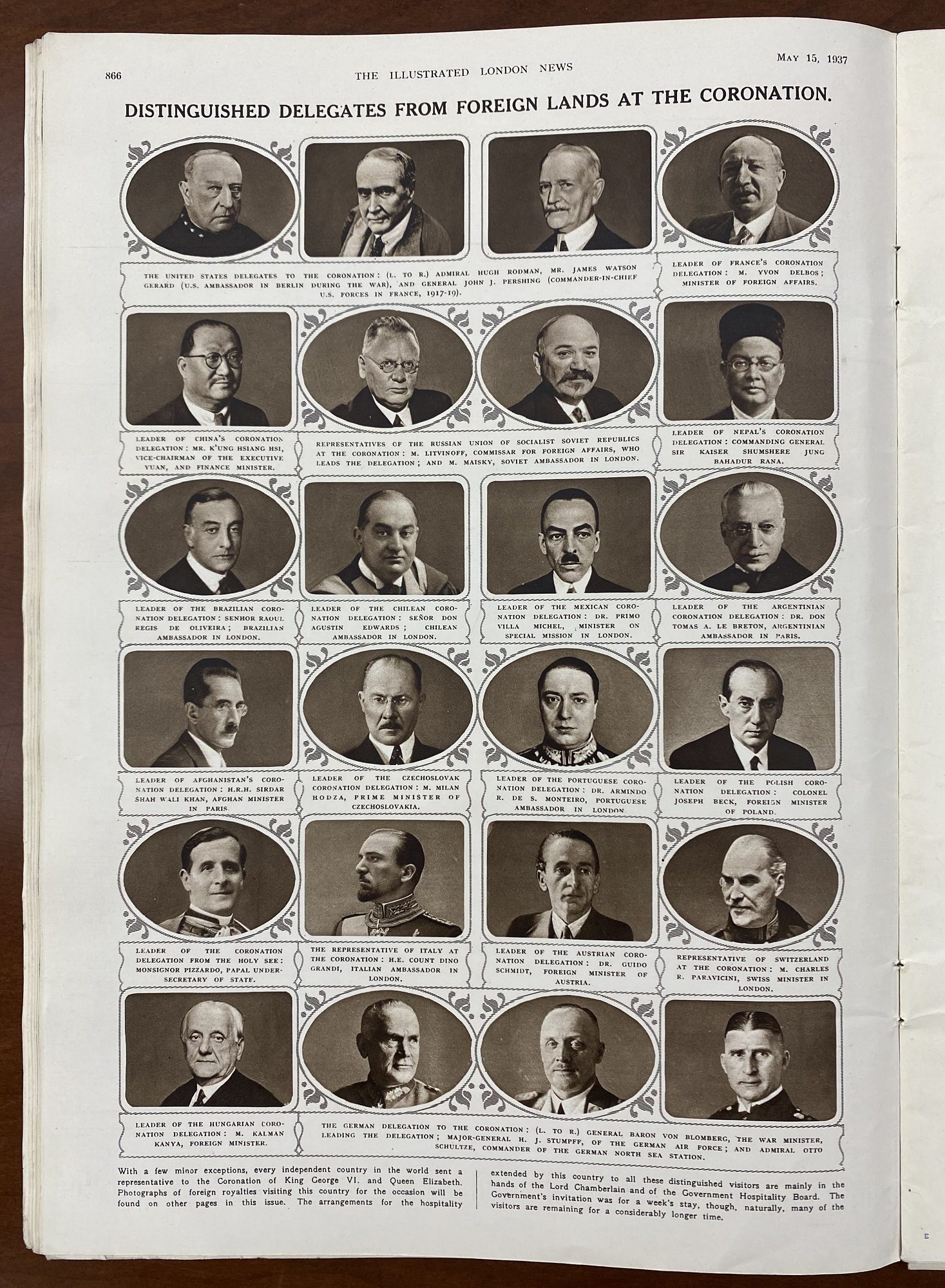

Another example of the omission of Black presence was the news coverage. In The Illustrated London News, the only African leaders pictured are the Sultan of Zanzibar and white colonial leaders such as J. B. M. Hertzog, and the only foreign delegates pictured hail from Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

The Illustrated London News, May 15, 1937, vol. 100, no. 2612. AP4.I3 FOLIO-B

In a cablegram Jackson sent to the ANP on May 13, 1937, she relays her observations of how Black dignitaries were treated: “. . . the coronation procession of King George VI gave Africa the poorest showing of all the countries represented. Among thirty thousand troops from Canada, New Zealand, India, the Union of South Africa, Malay, the West Indies and other members of the Colonial and Protectorate territories, only 25 barefoot native blacks marched at the tailend [sic] of the colonial contingent but the applause that greeted them was rivaled only by the deafening accalamation [sic] given to the majestic Indians who completely stole the show, even from Britain’s Navy men . . . The King’s escort of officers from the Colonial contingents contained no black faces, and African representatives, or distinguished visitors were shunted into the rear of a stand facing Buckingham where they could see little of the procession.”

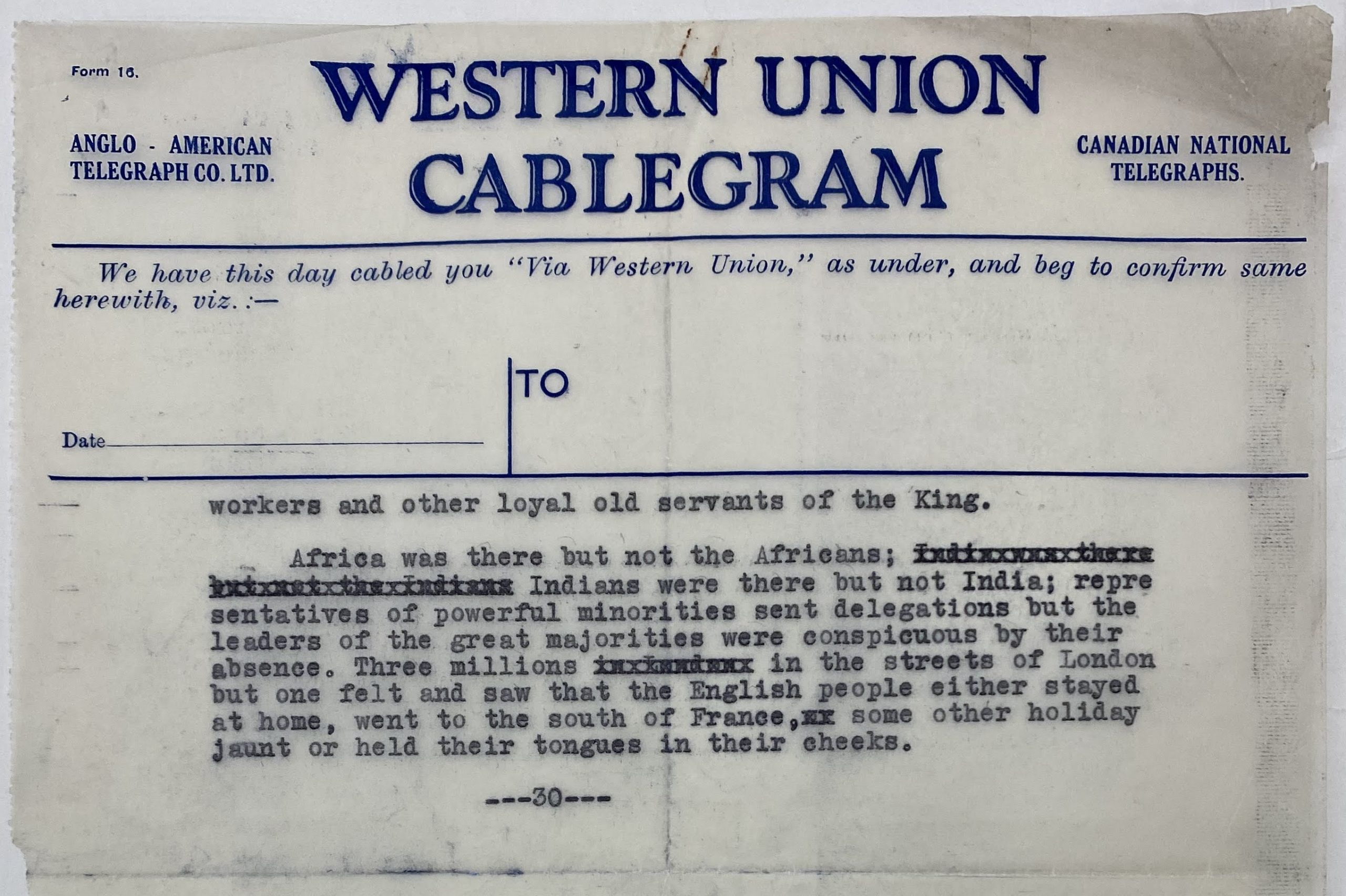

A cablegram from Jackson to Barnett, May, 13, 1937.

She continues with: “Africa was there but not the Africans; Indians were there but not India; representatives of powerful minorities sent delegations but the leaders of the great majorities were conspicuous by their absence.”

Fay Jackson’s reports were published in major Black newspapers in the US, including the California Eagle, and earned her praise. In a letter from Barnett to Jackson, he writes: “You have done a grand job and we are very proud of you. I suspect the acclaim to which the papers have hailed your exploit[s] and the personal appreciation which must be in the minds of thousands of folk throughout the country, will be some measure of compensation because, of course, our contribution is a mere mite outside of the channel of service in enabling you to do what you aspired to accomplish. It leaves you the No. 1 Negro newswoman anyway.”

Coauthored by CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman and CHM content manager & editor Esther D. Wang.

Additional Resources

- Learn more about the Claude A. Barnett papers [manuscript], 1918–67, at the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit

- Read more about Fay Jackson’s reporting partner, Rudolph Dunbar, whose papers are housed at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library

Experience the duality of feeling a deep connection to two places at once through firsthand storytelling.

CHICAGO (April 19, 2023) – Through the lens of Chicago’s Polish communities, the Chicago History Museum invites guests to experience the journeys immigrants have taken to get to our city. Including the ways people established themselves as a community in area neighborhoods and the duality of feeling a deep connection to two places at once. Back Home: Polish Chicago opens at the Chicago History Museum May 20, 2023.

“We hope that visitors will see Polish Chicago history as dynamic and ongoing and find stories in the exhibition that resonate with them,” says Peter Alter exhibition curator and Chief Historian at the Chicago History Museum. Chicago History Museum Project Historian Dominic Pacyga says, “Most Chicagoans know that the city has long had a large Polish population, but few realize Polonia’s long and complex history. This exhibition will allow Polish Americans and others to not simply celebrate the past, but to understand it, and place the Polish Chicago experience within a larger historical context. The extensive collection of artifacts, illustrations, maps, and personal histories in exhibit all help to illuminate this fascinating history.”

Back Home: Polish Chicago is a social history of Chicagoland’s Polish communities that uses first-person narratives and experiences to interpret over 150 years of history. Visitors will be able to listen to oral history snippets in a music and interview kiosk and read Polish Chicagoans’ words throughout the gallery, including in large wall quotations and in explanatory text. Art installations from five local Polish artists will also be incorporated. These art thresholds are placed throughout the exhibition between thematic sections and represent a culturally potent visual metaphor for the theme of moving between states of being, in the duality of Polish American identity and experience.

The exhibition will travel to Warsaw, Poland after showing at CHM. Polish History Museum Project Historian Joanna Wojdon says of this partnership, “The exhibition offers an opportunity to bring together the Polish and American experiences of the Polish American community of Chicago.” Photographs from the Dwell Studio project Kalejdoskop Polski, highlighting prominent members of Chicago’s Polish community will also be shown. When borrowing artifacts from families, organizations, and individuals for display, CHM has worked very closely with the lenders to make sure their stories and those of their ancestors are accurately and respectfully represented.

Members of the media are invited to preview the exhibition and interview the curators the week prior to opening. Visits can be scheduled for May 15-19 from 9:00am-5:00pm with Public Communications Manager, Veronica Casados at casados@chicagohistory.org.

Back Home: Polish Chicago is a collaborative project and oral history initiative with the Polish History Museum (Warsaw, Poland), Polish Museum of America, and Loyola University Chicago Polish Studies program.

Access the media kit: https://app.box.com/s/eyj7h9gmscmii5m8zf4qy690het7b1cb

###

The appearance of pink and white cherry blossoms in Chicago’s Jackson Park marks an end to winter and ushers in a long-awaited spring. In this blog post, CHM curatorial intern Eva Mazzeno talks about the history behind those trees and Chicago’s connections to Japan and Shintō.

Entrance to Garden of the Phoenix and cherry blossoms blooming at Jackson Park, 2023. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman

In Chicago’s Jackson Park, Wooded Island has served as a center of Japanese architecture and culture since the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE). There you can find nearly 190 cherry blossom, or sakura, trees, which the nonprofit Project 120 and the Japanese Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Chicago (JCCC) planted between 2013 to 2016 to mark the 120th anniversary of that world’s fair and the 50th anniversary of JCCC’s founding of in 1966. Each spring, the blossoms invite visitors to engage in hanami, the traditional art of flower viewing.

Construction on the Japanese Wooded Island for the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1892. CHM, ICHi-023716

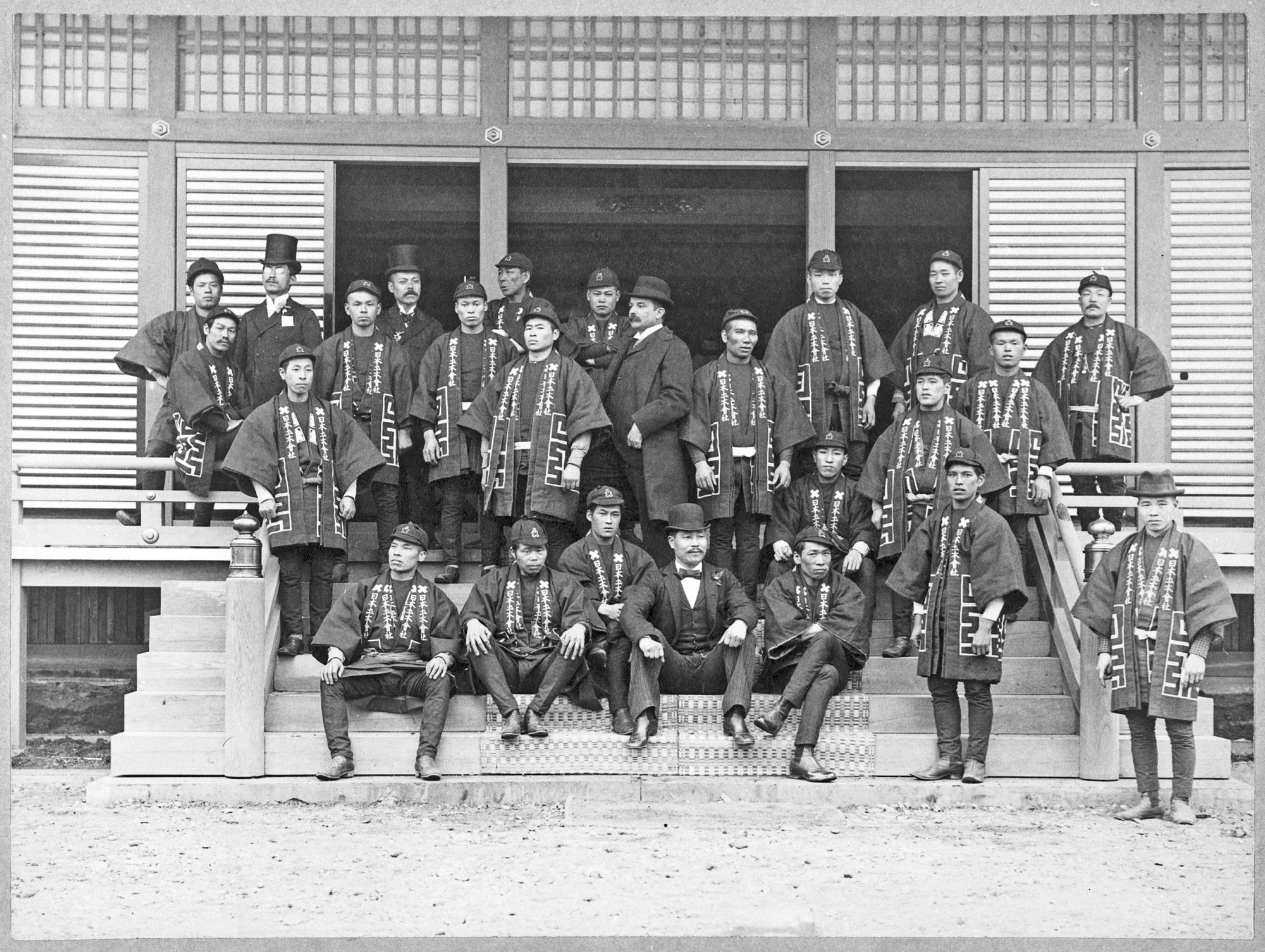

Chicago’s connections with Japan date back to 1893, as Japan was one of the first foreign supporters of the WCE, contributing around $600,000 in total, and the Japanese Pavilion, or Hō-ō-den, was a stunning architectural contribution. Twenty-four highly skilled Japanese carpenters constructed the pavilion using prefabricated materials shipped directly from Japan as a replica of Byōdō-in, a Buddhist temple in Kyōto. The pavilion was gifted to the city of Chicago as a permanent installation—one of only a handful of permanent structures in the fair.

The Japanese Hō-ō-den Temple Complex at the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893. CHM, ICHi-031718; John George M. Glessner, photographer

People at the Japanese Hō-ō-den, World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893. CHM, ICHi-020829

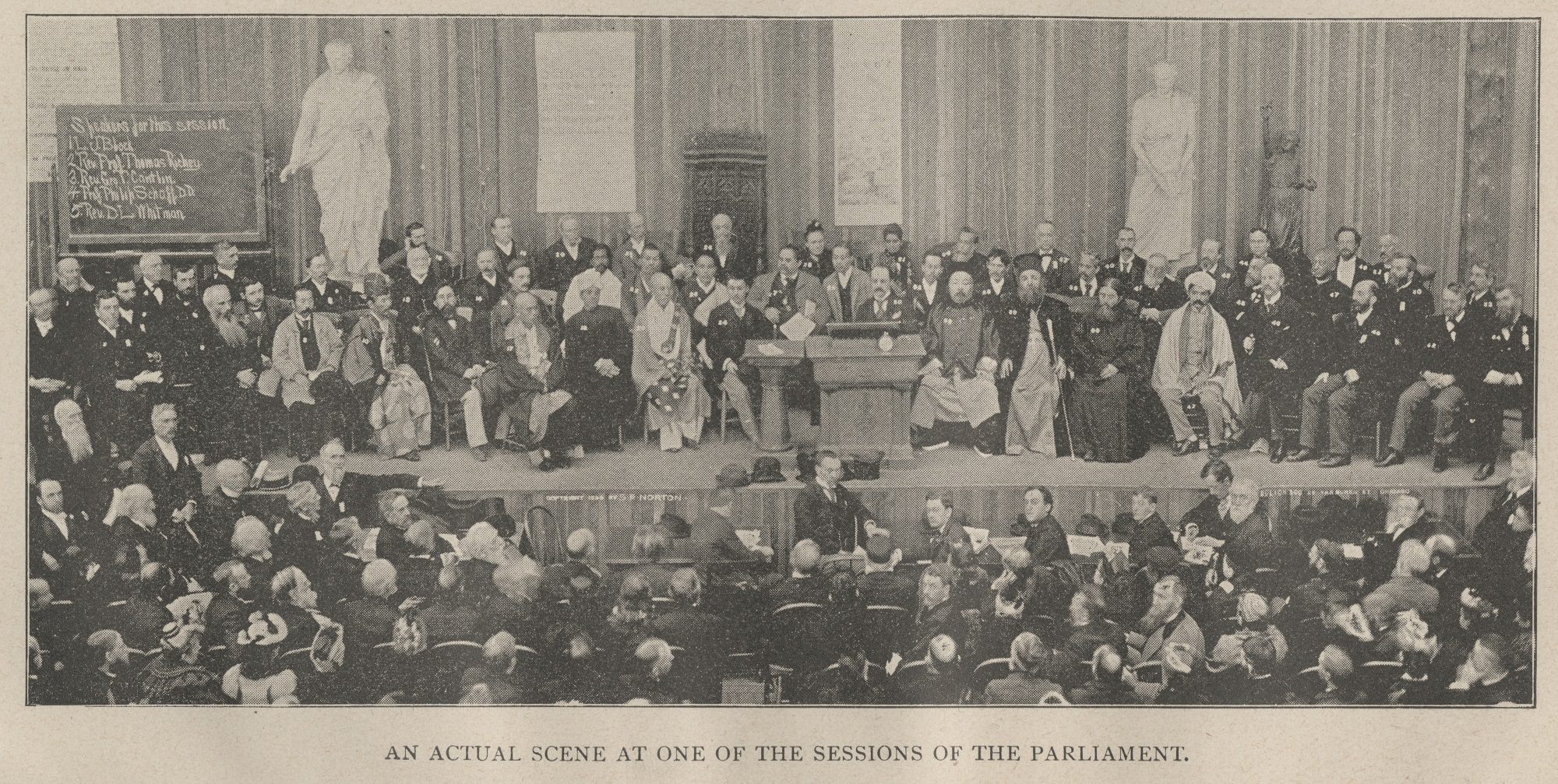

Several Japanese delegates also took part in the Parliament of the World’s Religions, the world’s first interfaith gathering of its kind. While most participating Asian nations sent only one or two members, Japan boasted several delegates representing the nation’s two major religions: Buddhism and Shintō. Varying schools of Buddhism can be found across the globe, but Shintō’s roots are solely within Japan. Shintō is the worship of kami—sometimes translated as “spirits”—which can be found in nature and the “heart-mind” of humans.

“An Actual Scene at One of the Sessions of the Parliament” from The World’s Parliament of Religions: An Illustrated and Popular Story, Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-062640

Buddhism and Shintō had long coexisted in Japan, but two governmental decrees in 1868 and 1871 drastically shifted religious practices by officially separating Buddhism from Shintō. Buddhists were ordered to operate their own temples, and Shintō practices abandoned any usage of Buddhist terminology. As a result, by the time of the 1893 world’s fair, Japanese Buddhists were eager to firmly establish themselves both nationally and internationally and shape global perceptions of Buddhism. All but one of Japan’s delegates to the Parliament were Buddhists, with only Reiichi Shibata to represent Shintō.

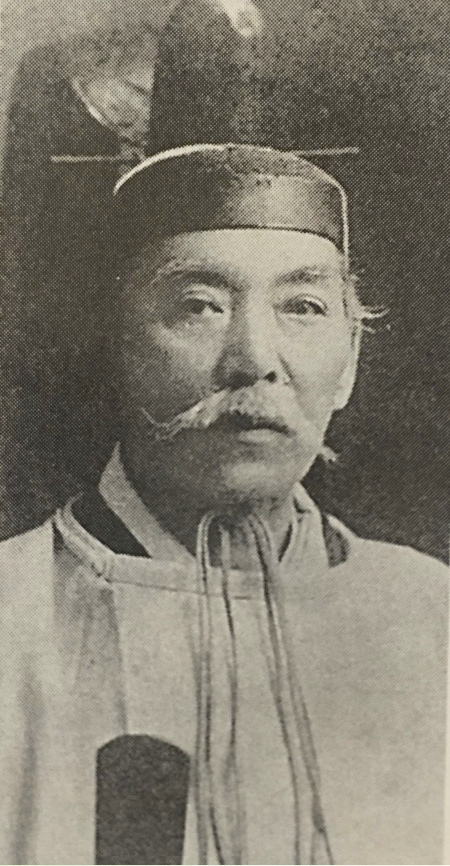

Reiichi Shibata, c. 1900. From Brochure for Jikko-Kyo Shintōism. Courtesy of IMAI Koichi.

Reiichi Shibata (1840–1920) was the second high priest and president of the Jikkōkyō sect of Kyōha Shintō from the Shibata family, inheriting the position in 1890 after the death of his father, Hanamori Shibata. Shibata had been president of the Jikkōkyō sect for just three years by the time of the WCE, taking the reins of one of Shintō’s largest denominations just before its debut on the global stage. Unlike many of the other religions presented at the Parliament, Shintō was almost entirely unfamiliar to American audiences, and it faced sharp scrutiny and racist criticism upon its introduction. Shibata did not engage with accusations, instead choosing to present Shintō in the context of the Parliament’s greater goal “to bring the nations of the Earth into more friendly fellowship, in the hope of securing permanent international peace.”

Upon his return to Japan, Shibata continued to advocate for world peace, especially through the creation of a unified body for international cooperation and the furthering of the growing interfaith movement. He assisted with the founding of the Shintō Dōshikai—now called the Kyōha Shintō Federation—in 1895, an intrafaith coalition of Shintō sects, in which he actively participated until his death. Today, the Shibata family still leads Jikkōkyō Shintō, and Reiichi Shibata is widely credited for his many significant advancements in global Shintō visibility and participation in intra- and interfaith movements.

Sky Landing by Yoko Ono on the original site of Hō-ō-den, 2023. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Wooded Island has undergone significant changes since the WCE. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, Hō-ō-den fell into disrepair, and in 1946, it was destroyed completely in an arson attack. In the decades after, however, efforts were made to revitalize the island. Today, Sky Landing (2016), a sculpture by Yoko Ono, Japanese artist and musician, can be found there. Since 1973, Chicago and Ōsaka—Japan’s second largest city—have shared a sister city relationship, opening the door to additional transnational cultural and economic opportunities.

Ginza Holiday, Chicago, c. 1962. CHM, ICHi-111463, Raeburn Flerlage, photographer

Every year, Chicago’s Midwest Buddhist Temple hosts the Ginza Holiday, a celebration of Japanese culture and arts. In the 130 years since Reiichi Shibata’s visit, Chicago’s Japanese American community has thrived, becoming an irreplaceable piece of the city.

Chicago History Museum Opens Digitial Access to the Sun-Times Collection

The photography collection spanning 75+ years of Chicago history is now available to the public.

CHICAGO (April 12, 2023) – In 2018 the Chicago History Museum acquired a Chicago Sun-Times photography collection of over 5 million images spanning over 75 years of Chicago history. It is one of the largest newspaper photograph collections ever acquired by an American museum. The collection consists primarily of 35-millimeter negatives and digital images documenting events from as early as the 1940s through the 2000s. To ensure long-term preservation and access, the Museum worked closely with the Chicago Sun-Times to acquire the collection, which was sold by private collectors. Since the acquisition CHM staff have been working hard to make these pieces of history publicly available. Today, the Museum is excited to announce that the public can access online approximately 2 million of the 5+ million images the Museum acquired in 2018. The remaining digital images in the collection will be added over the next few months and by the end of June 2023, the remaining 600,000 images will be available for research use online. An additional 2.4 million physical negatives will be available to view in person, by appointment and advance request, at the Abakanowicz Research Center.

“Digital materials are often even more expensive and time-consuming to care for than their physical counterparts. A collection of this size and complexity requires a deep commitment, not just of resources but also from staff, to steward it over years of work,” says Julie Wroblewski, Director of Collections. “The Chicago Sun-Times is noted for the work of its photographers, and the breadth and quality of these images is unparalleled. It means a great deal to the Museum and the archival staff that our work ensures the long-term preservation and public accessibility of these materials.”

You can learn more about accessing the digital collection at this link. Visitors to the Museum can also see highlights in the exhibition Millions of Moments: The Chicago Sun-Times Photo Collection, which features 150 images. Showing at the Museum until September 2023.

Highlights from the collection include:

- Early events of the Civil Rights era, including school busing, segregated housing, Black Panther activities, and notable leaders in Chicago such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Muhammad Ali, Dick Gregory and Jesse Jackson

- Local and national politics, including activities of Chicago mayors Richard J. Daley, Richard M. Daley, Harold Washington and Jane Byrne; party conventions; and presidential visits

- Sporting events, including Chicago’s professional teams, university sports, high school athletics and Special Olympics

- Built environment, including South and West Side neighborhood scenes, iconic architecture and public housing

- The work of several award-winning photographers, including Pulitzer Prize winners Jack Dykinga (1971) and John H. White (1982); Bob Black, winner of the 1984 World Press Photo award in the Daily Life, Singles category; and Pablo Martínez Monsiváis, who later won a Pulitzer Prize (1999) as an Associated Press photographer.

Processing of the Chicago Sun-Times collection is generously supported by the TAWANI Foundation, the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation, and Bon and Holly French. Funding for Millions of Moments provided by Jamee & Marshall Field V and DePaul University.

###

In 2018, the Chicago History Museum acquired the Chicago Sun-Times photography collection, which spans from the 1940s to the early 2000s—one of the largest newspaper photograph collections ever acquired by an American museum. In this blog post, CHM metadata librarian Izzy Westcott explains how the massive collection was processed and made searchable to the public.

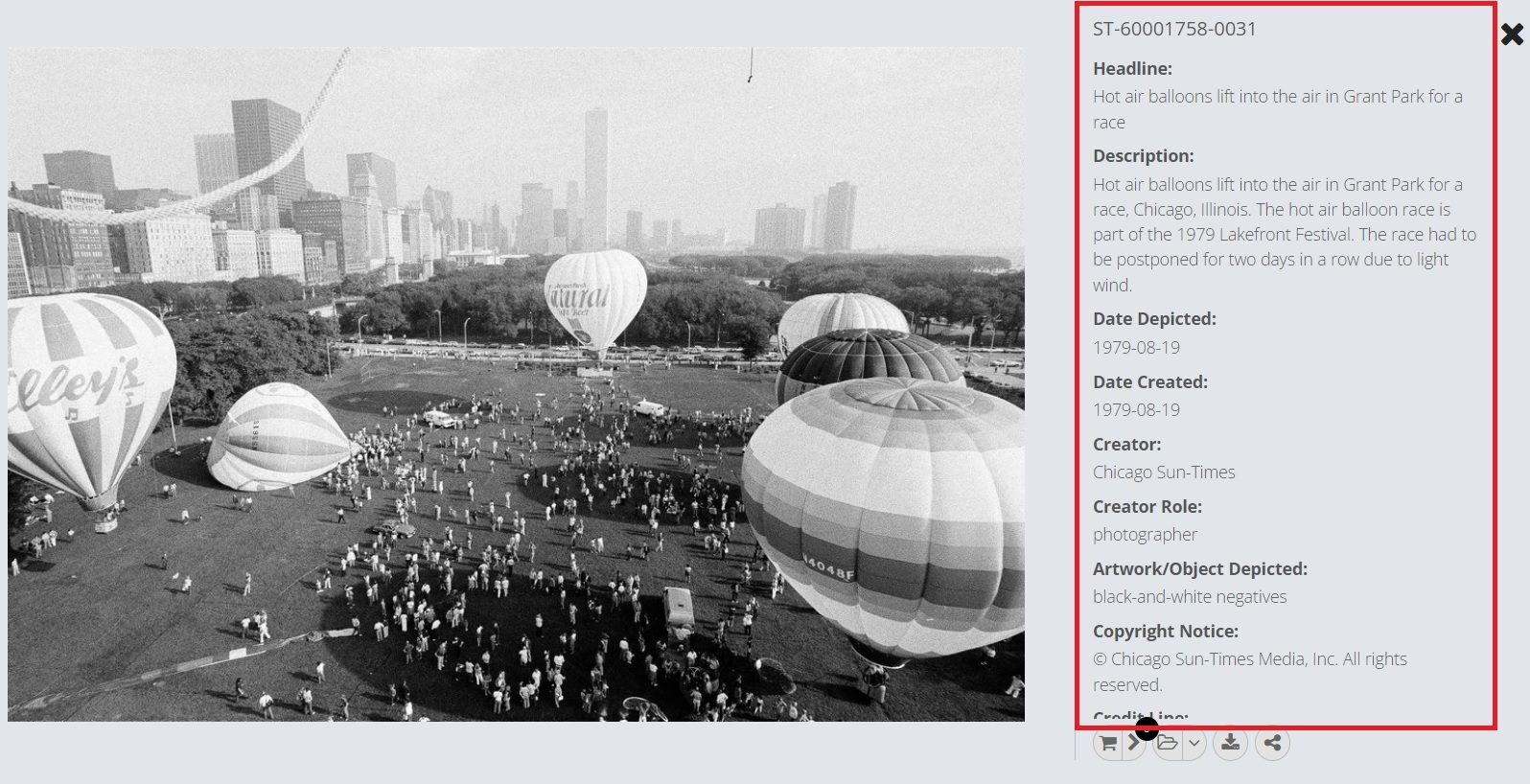

An example of metadata (in red box) as seen on our online image portal, CHM Images. Hot air balloons lift into the air in Grant Park for a race, Chicago, August 19, 1979. ST-60001758-0031, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

1. What is your role at the Museum and how did you contribute to the Chicago Sun-Times collection project?

As the metadata librarian for the Chicago Sun-Times photography collection, I reviewed, edited, and organized collection’s descriptive metadata (information about the content of the materials). This included the creation of publicly accessible Airtable databases, which act as inventories for more than 2.5 million images.

I started this year-long position in spring 2022, and after familiarizing myself with the history of the collection and Airtable itself, I got to work cleaning and enhancing the collection’s metadata. Thanks to the many interns and staff who contributed to this project before me, a significant portion of the collection had already been enhanced, with precise descriptions, topic assignments, and location data. I continued this work by using Airtable’s features to move systematically through the collection. I tracked my progress as I reviewed date and topic fields, assigned topics and addresses, and enhanced or adjusted descriptions. I worked through the collection to tackle as much as possible, while also acknowledging that, due to the volume of the collection, I would not be able to review or enhance every job.

In addition to enhancing metadata, I also created publicly accessible databases in Airtable where researchers can search for images and access links to digital image files. This process involved combining sets of metadata that had previously been separated and performing user testing to evaluate the databases. Lastly, with the help of colleagues, I created the Sun-Times Collection research guide, which provides access instructions and search strategies.

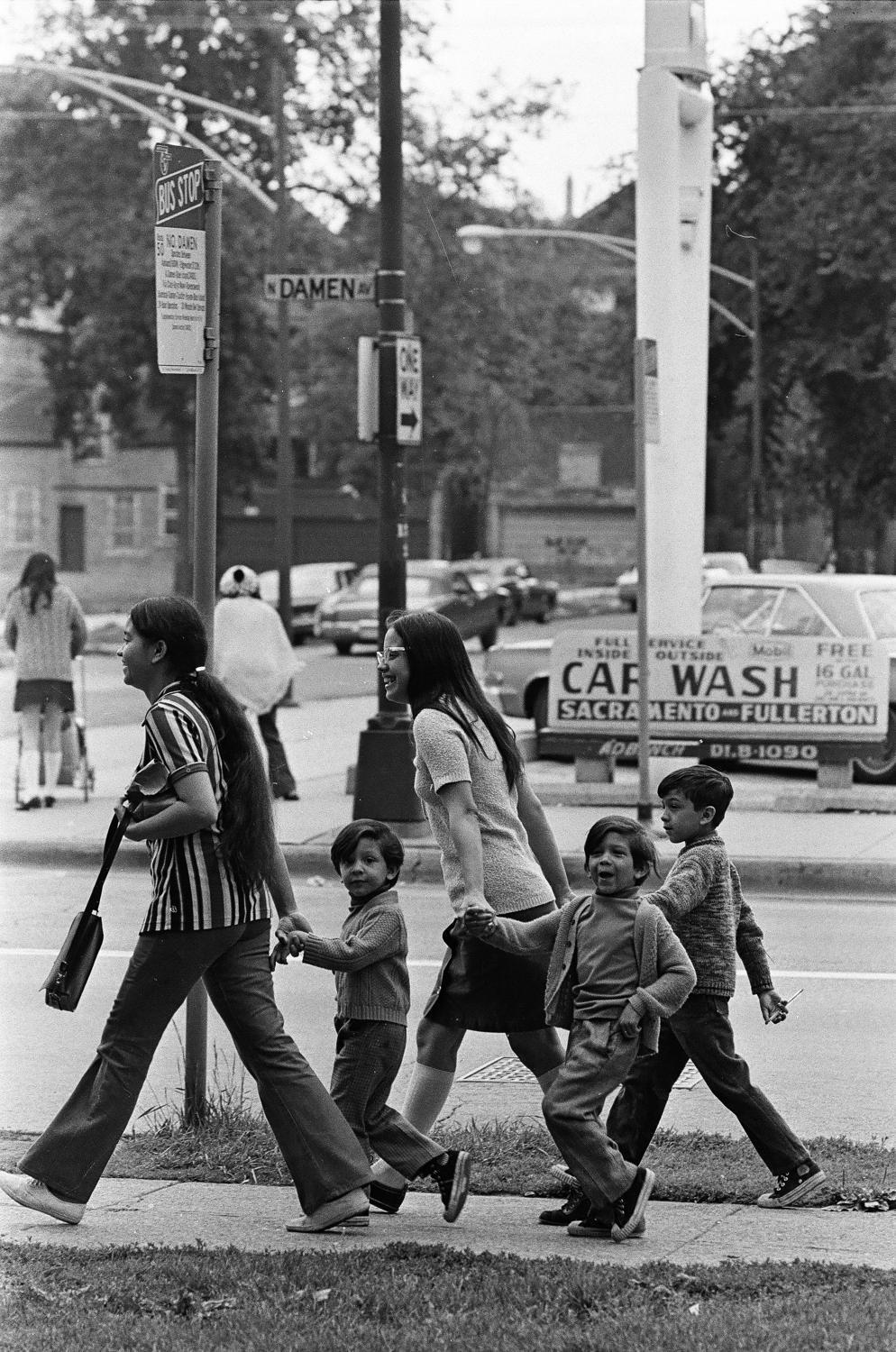

Pedestrians along Damen Avenue, Chicago, July 1972. ST-13003696-0007, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

2. What is one photograph or series of photographs that you found particularly striking. and why?

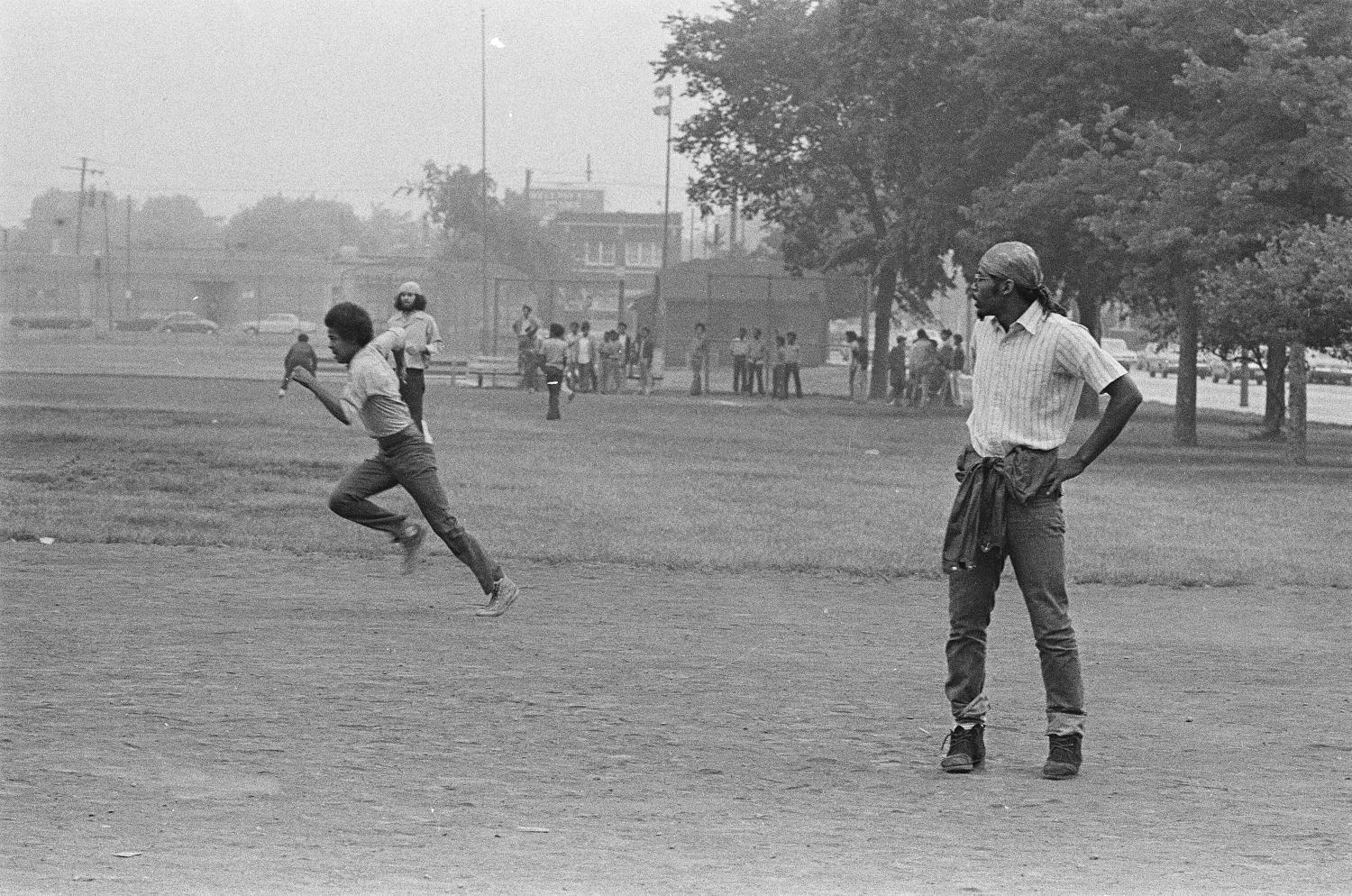

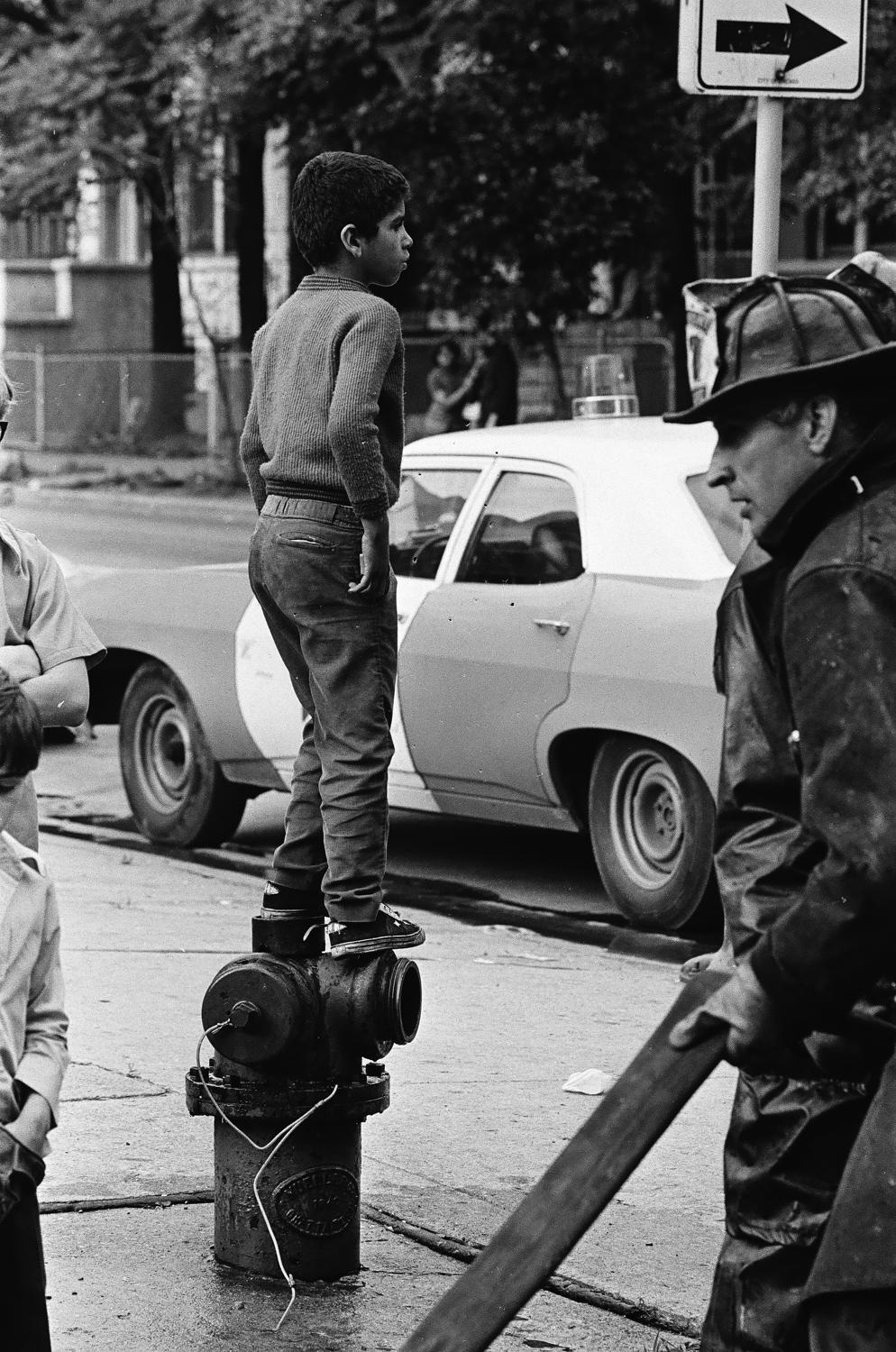

I came across a job with the headline “Street” and the description “Rosehill cemetery.” However, of the 156 images in the job, number 13003696, only a small portion depicted the cemetery. There were also images of other parts of the city, including a baseball game, a playground, and people gathered on a park bench. The images did not obviously appear connected to one another. I could not find anything with a similar description in the Chicago Sun-Times Historical Archives from around that date, July 1972.

People playing in a field, Chicago, July 1972. ST-13003696-0041, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

A child in a park taking a self-portrait, Chicago, July 1972. ST-13003696-0081, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

After examining the images for location details and street addresses, I began to suspect they all depict locations along Damen Avenue. I imagined a Sun-Times photographer driving the entire length of the street, from Beverly all the way up past the cemetery, stopping and snapping pictures whenever they saw something interesting. Although this job is unusual for the collection, as most jobs contain images taken at one specific event or location, I think it’s a striking example of the range and scope of the Sun-Times photographs. The collection provides valuable documentation of major events and notable people, but it also captures the daily lives of Chicagoans and offers a chance for researchers to explore the history of the city.

A child standing on top of a fire hydrant, Chicago, July 1972. ST-13003696-0084, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

3. Was there anything unexpected or surprising you encountered or learned during the digitization process?

As impressive as this collection is, it was certainly more challenging to work with than I expected. The sheer size of it alone has meant that we were unable to approach it the way we would more traditional collections.

One of the biggest challenges we faced was how to connect the metadata for the images, stored in Airtable, to the images themselves, stored primarily in Box. Airtable does offer Box integrations, but not when working with over 10,000 records (and we have over 200,000!). And while Box has great options for sharing links, those links do not provide a search feature, so researchers would not be able to copy and paste the job number to search for the corresponding images.

With a few other roadblocks in our way, we came up with a solution that would be efficient on our end, while also providing the smoothest path possible for our researchers. Making custom URLs for folders in Box allowed us to build a formula in Airtable that would create links for us, rather than having to copy and paste each one. You can learn more about this process and accessing images in the Sun-Times Collection research guide.

About the Author

About the Author

Izzy Westcott joined the Chicago History Museum in spring 2022 as a metadata librarian. The one-year position is part of the grant-funded project to process and digitize the Chicago Sun-Times visual materials. Westcott has a MLIS from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman talks about the significance of Easter and shares a brief history of Chicago’s Polish Catholic community.

Easter Service at Holy Trinity Church, April 1988. CHM, ICHi-039082; Richard Younker, photographer

For Roman Catholic and Protestant Christians, Easter is one of the central Christian holidays. It comes at the culmination of Holy Week, which begins on Palm Sunday and includes Maudy Thursday (the day commemorating Jesus’s Last Supper), Good Friday (the day commemorating Jesus’s death), Holy Saturday (the day of vigil), and ends with Easter Sunday (the day commemorating Jesus’s resurrection). Holy Week is generally filled with special services and rituals as a time of somber reflection with Easter serving as a day of celebration. Traditions such as dyeing and decorating eggs and blessing and exchanging baskets speak to this symbolism of coming rebirth, renewal, and abundance.

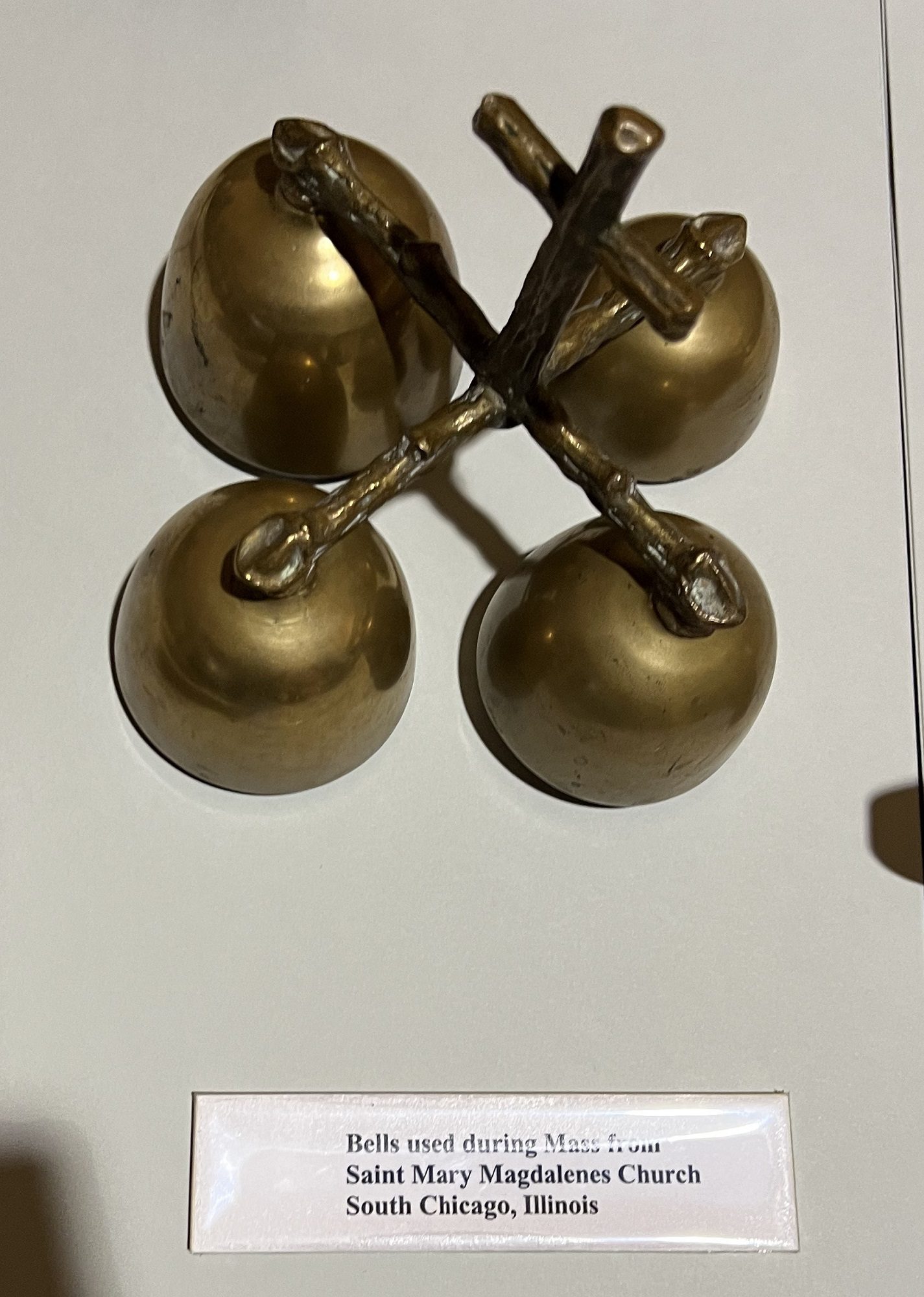

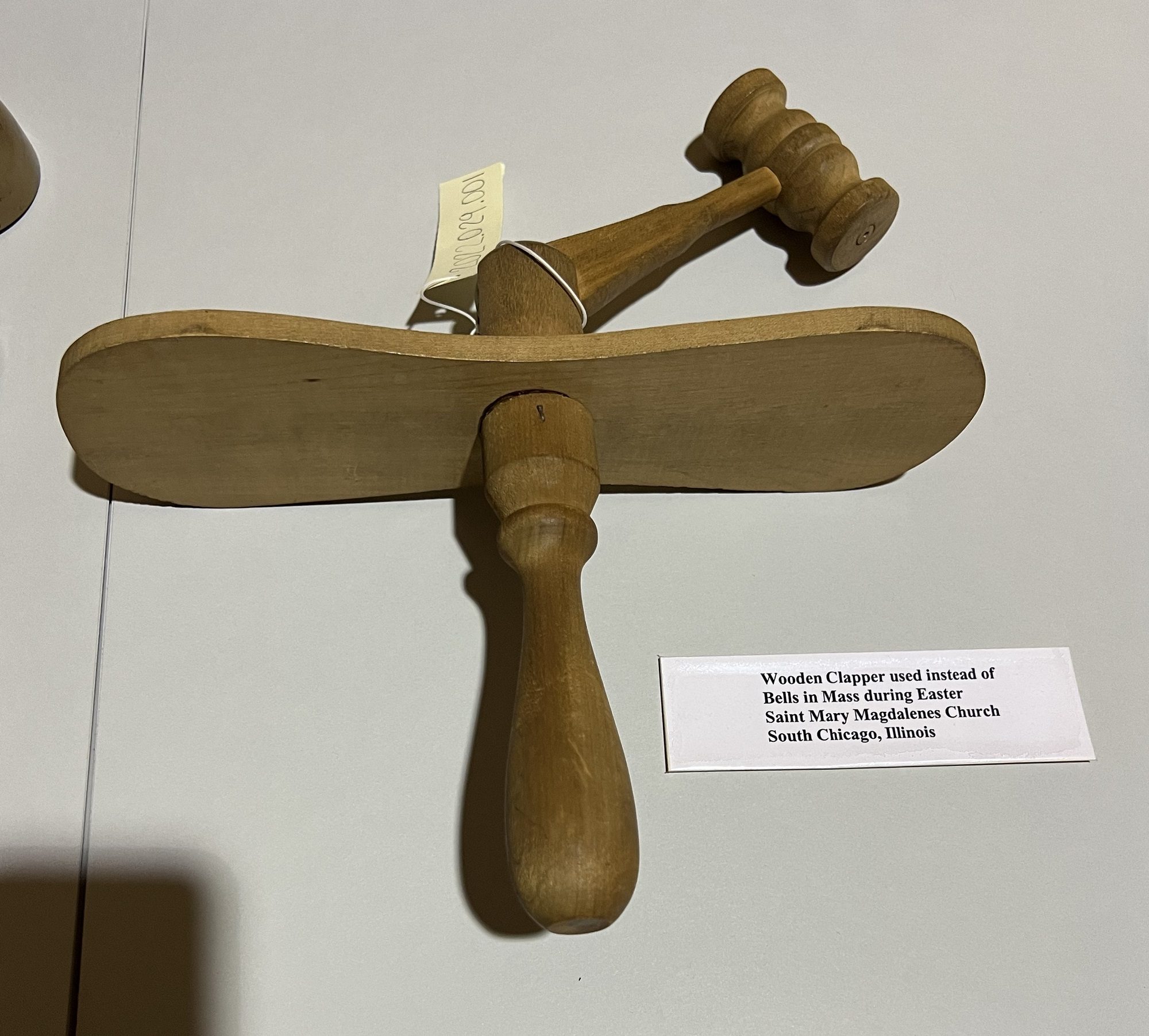

St. Mary Magdalene Church bells (above) and clacker (below), n.d. Courtesy of the Polish Museum of America. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

As part of Holy Week traditions, church services feature special liturgies, songs, prayers, and practices to reflect the somber period. For example, in Catholic tradition, bells are generally used to bring attention to holy moments during the service. From Maundy Thursday to Easter Sunday, a crotalus, or clacker/clapper, is used instead of bells to mark the period of mourning. This set of bells and the clacker (above) are examples that were used during services in St. Mary Magdalene Church, a former Polish Catholic congregation in South Chicago.

St. Stanislaus Kostka in Pulaski Park, Chicago, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

For many of Chicago’s immigrant communities, houses of worship have been built as symbols of identity. Polish migration to Chicago began in the 1830s and became more established in the 1850s. As the Polish Catholic community became more settled, Polish Cathedral-style churches dotted the landscape, defining and demarcating neighborhood spaces. In the 1860s, the first Polish Roman Catholic parish was established, St. Stanislaus Kostka. During the next century, more than fifty Catholic parishes were established that either identified as Polish or had Polish-majority congregations, including in the city’s Northwest, Near West, and South Sides.

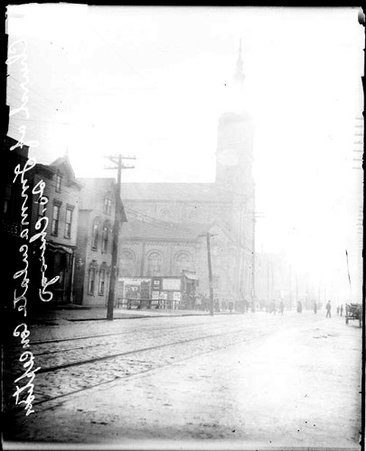

Church of the Immaculate Conception at 88th St. and Commercial St. in South Chicago, January 23, 1909. DN-0053852, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

In South Chicago, the neighborhood grew in tandem with the growth of the steel mill industry. Many Polish immigrants settled in the ethnically diverse industrial area for jobs, and community institutions soon followed. The first Polish church in the area was Church of the Immaculate Conception (Kościół Niepokalanego Poczęcia Najświętszej Maryi Panny), founded in 1882. It was the mother church to three additional Polish parishes in South Chicago, one of which became St. Mary Magdalene.

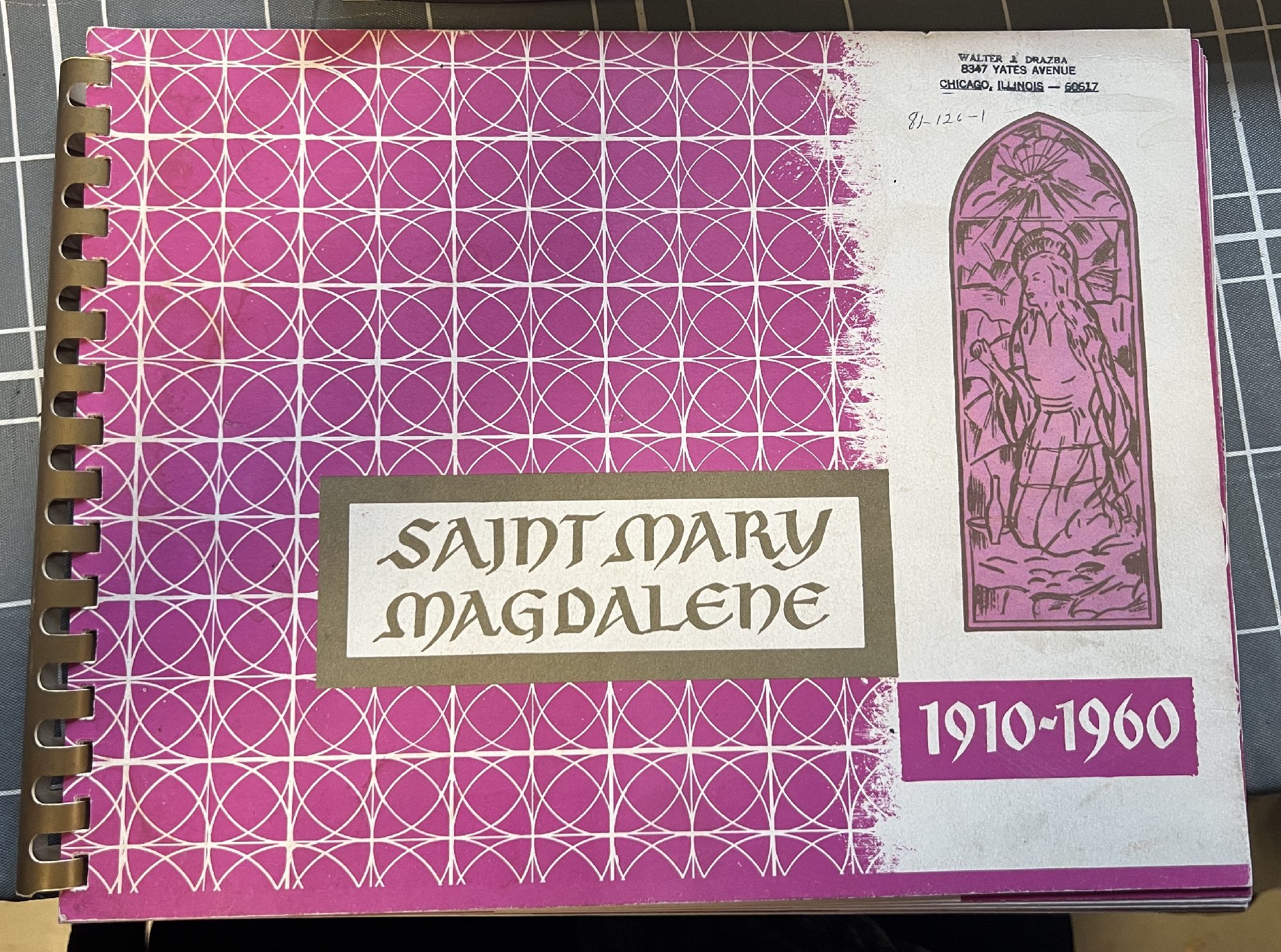

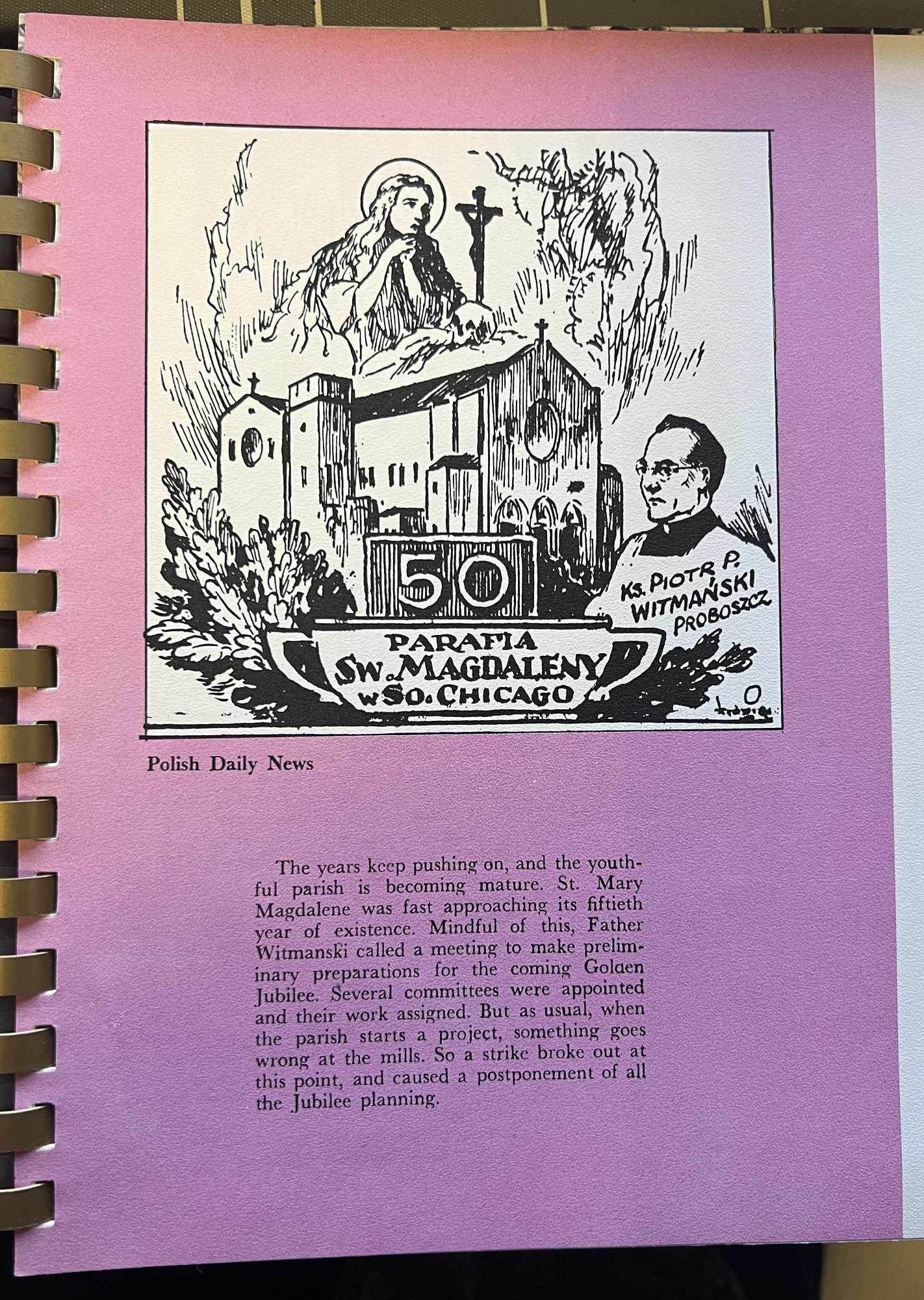

Saint Mary Magdelene 50th Anniversary commemorative book, 1960. Booklet from the collection of the Southeast Chicago Historical Society. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman

St. Mary Magdalene Parish was founded in 1910 under the leadership of Rev. Edward Kowalewski, and its first building was dedicated in 1911. After the start of the Great Depression in 1929, the steel industry declined and with it the parish’s financial security. After this period of instability, the 1940s brought renewed hope and financial prowess for the parish as the surrounding neighborhood was at a peak of Polish presence, and in 1952 ground was broken for a new building at 84th Street and Marquette Avenue.

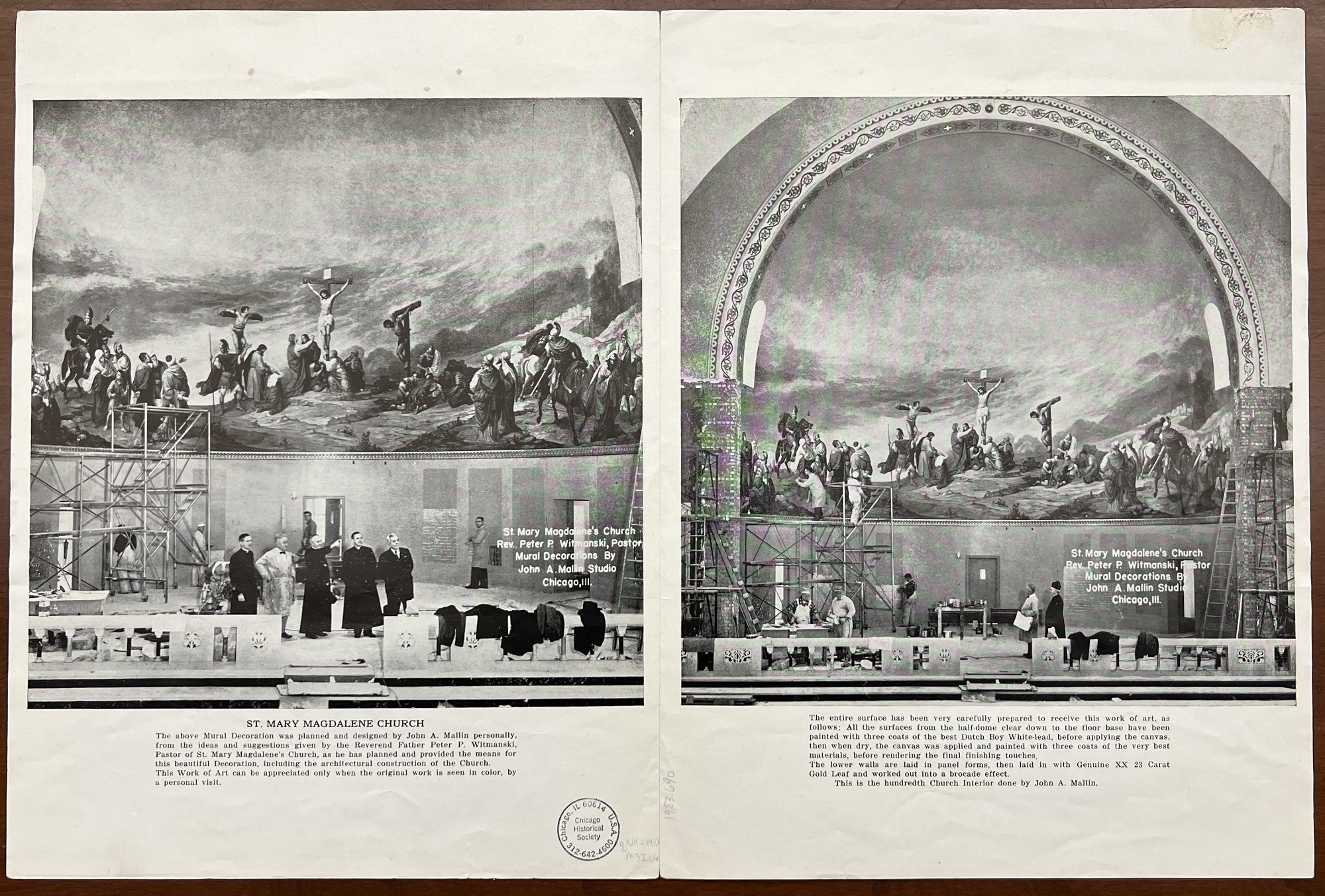

Interiors of St. Mary Magdalene Church by Rev. Peter P. Witmanski, pastor. CHM collection, NK2190.M3 I66 OVERSIZE. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

The church’s new sanctuary featured elaborate paintings by John Mallin, a Czech American artist based in Chicago. Mallin was known for painting more than 100 churches in his career, including other Polish majority churches in the Chicago area, including St. Hyacinth Basilica, St. Hedwig’s, St. Mary of the Angels, and St. Mary of Czestochowa, among others.

Interior of St. Hyacinth Basilica in Avondale, Chicago, featuring paintings by John Mallin, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

When the second St. Mary Magdalene Church was dedicated in 1954, South Chicago was already experiencing a shift as preceding European immigrants began moving to the south suburbs and Serbian and Croatian refugees arrived. By the 1980s, the neighborhood was majority African American and Latino/a/x, primarily Mexican. The 1980s and ’90s also saw the decline and eventual closure of the steel mills, leading to major economic and environmental repercussions for the area. St. Mary Magdalene formally closed as a church in 2015, and its building has now been adaptively reused as a charter school.

The former St. Mary Magdelene Church building today used as Great Lakes Academy charter school. Photographed 2022 by Rebekah Coffman

Additional Resources

- Learn more about Chicago’s Polish communities in Back Home: Polish Chicago

- Read more about Polish Chicago in our Encyclopedia of Chicago entry

Spend the summer uncovering Latino/a/x stories at the Chicago History Museum

CHICAGO (April 5, 2023) – The Chicago History Museum has openings for 8 Research Associates from June 26 through Aug 18, 2023. Young people from across the city are invited to apply and will contribute to the research for the upcoming exhibition, Aquí en Chicago, opening in fall 2025 at the Chicago History Museum.

Aquí en Chicago, is a response to protests by high school students from Rudy Lozano Academy against CHM for lack of Latino/a/x representation. The exhibition will situate their protest in a long history of 170 years of Latino/a/x resistance to white supremacy and colonialism, as well as presence, and cultural maintenance in Chicago. Aquí is only one part of the museum’s effort to redress a long history of omitting Chicago’s communities of color from its central narrative. The project is also a community-driven initiative that will prepare CHM to share the diverse historical narratives of Latino/a/x people and their integral contributions to the city, setting up the Museum to do more, ongoing work over the long haul beyond the exhibition’s opening.

Positions are open to people ages 16–20 who are not yet attending university. Expected work time is 15 hours per week with payment at $16 an hour for 8 weeks. Applications are due Sunday, April 23. The application is open and available in English and Spanish.

Media Kit: https://app.box.com/s/nc9hj30kgengwq7zl90p1yb2c66jvt98

###

CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman talks about the significance of Passover and shares a brief history of Chicago’s Jewish communities.

Sundown on Wednesday, April 5, 2023, marks the beginning of the Jewish holiday of Pesach or Passover. Celebrated by the Jewish diaspora for eight days, it is a time to remember the biblical story of Moses leading the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt. Also known as the Feast of Unleavened Bread, Passover is remembered through removing all chametz (yeast) from one’s home and not eating anything yeast-leavened for the days of remembrance as a form of sacrifice and a representation of removing sin from one’s life.

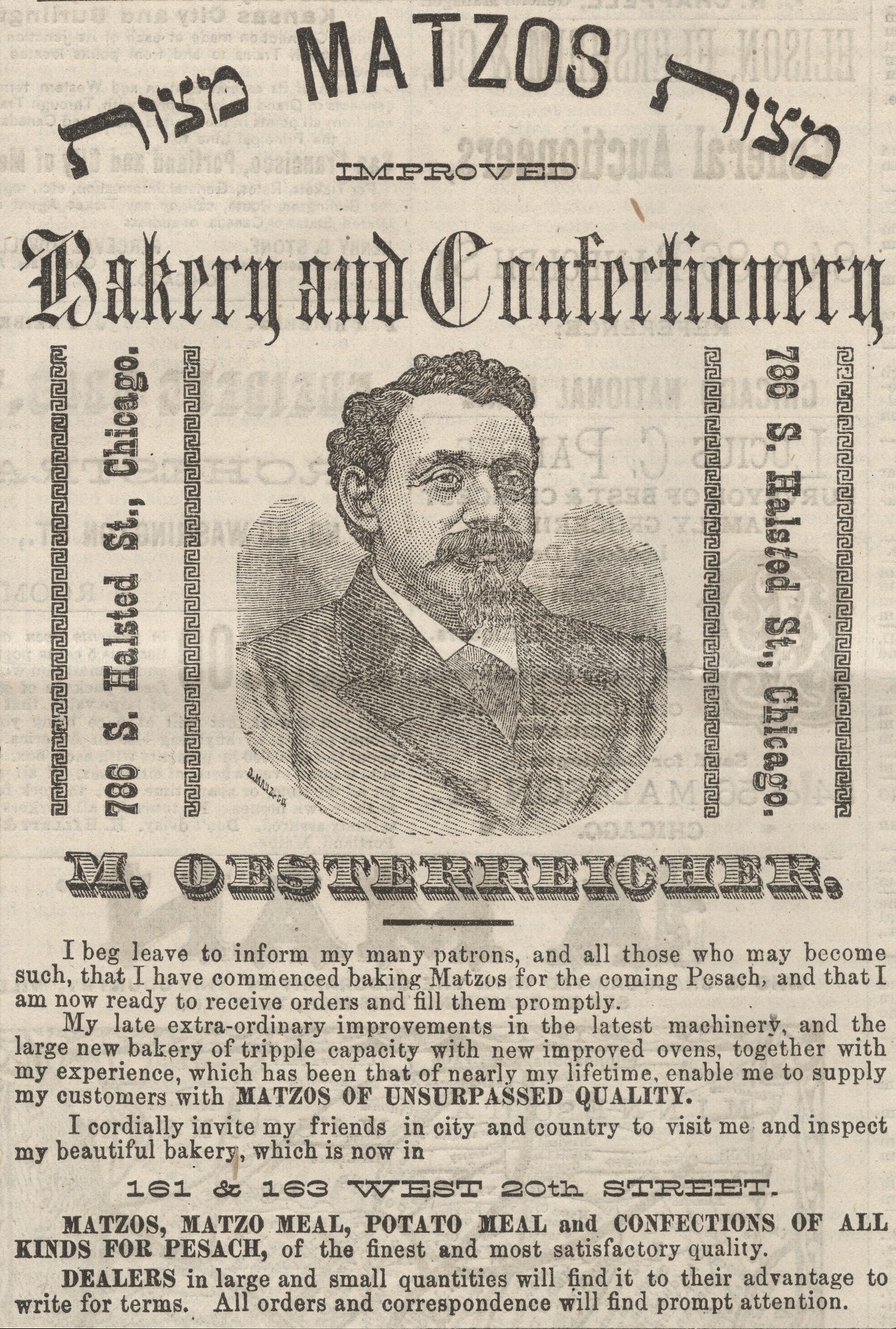

Left: Advertisement for M. Oesterreicher Bakery and Confectionery at 786 S. Halsted St. from The Occident Newspaper, 1885. CHM, ICHi-067038. Right: Advertisement for the Wittenberg Matzoh Co. at 1326 S. Jefferson St., from The Sentinel Newspaper, March 18, 1937.

Another important part of the tradition is the Passover seder meal. Jewish families gather and ritually retell the story of the Exodus from Egypt through eating symbolic foods and drinks and reading from a text known as the Haggadah.

Two editions of Temple Isaiah Israel’s Temple Tidings, March 1937. From MSS Lot K.A.M. Isaiah Israel, CHM collection.

These 1937 congregational bulletins from Temple Isaiah Israel share the meaning of Passover and the Seder meal as part of their Passover editions of Temple Tidings. Inside the March 17 edition is a description of the elements needed for a seder and instructions for community members on the proper ways to prepare the table in remembrance. One of the central foods of Passover is matzah (plural matzos), a specific type of flat bread made of just flour and water, that is eaten in place of yeasted bread at every meal.

March 17, 1937, edition of Temple Isaiah Israel’s Temple Tidings. From MSS Lot K.A.M. Isaiah Israel, CHM collection.

As the bulletin describes, three matzos are included at the seder meal on a large platter, known as a seder plate, along with a shank bone, a roasted egg, horseradish, haroses (a mixture of fruits, nuts, and spices), parsley, and salt water. Each of these foods is eaten at specified times as the Haggadah is read, and they are accompanied by drinking four symbolic glasses of wine.

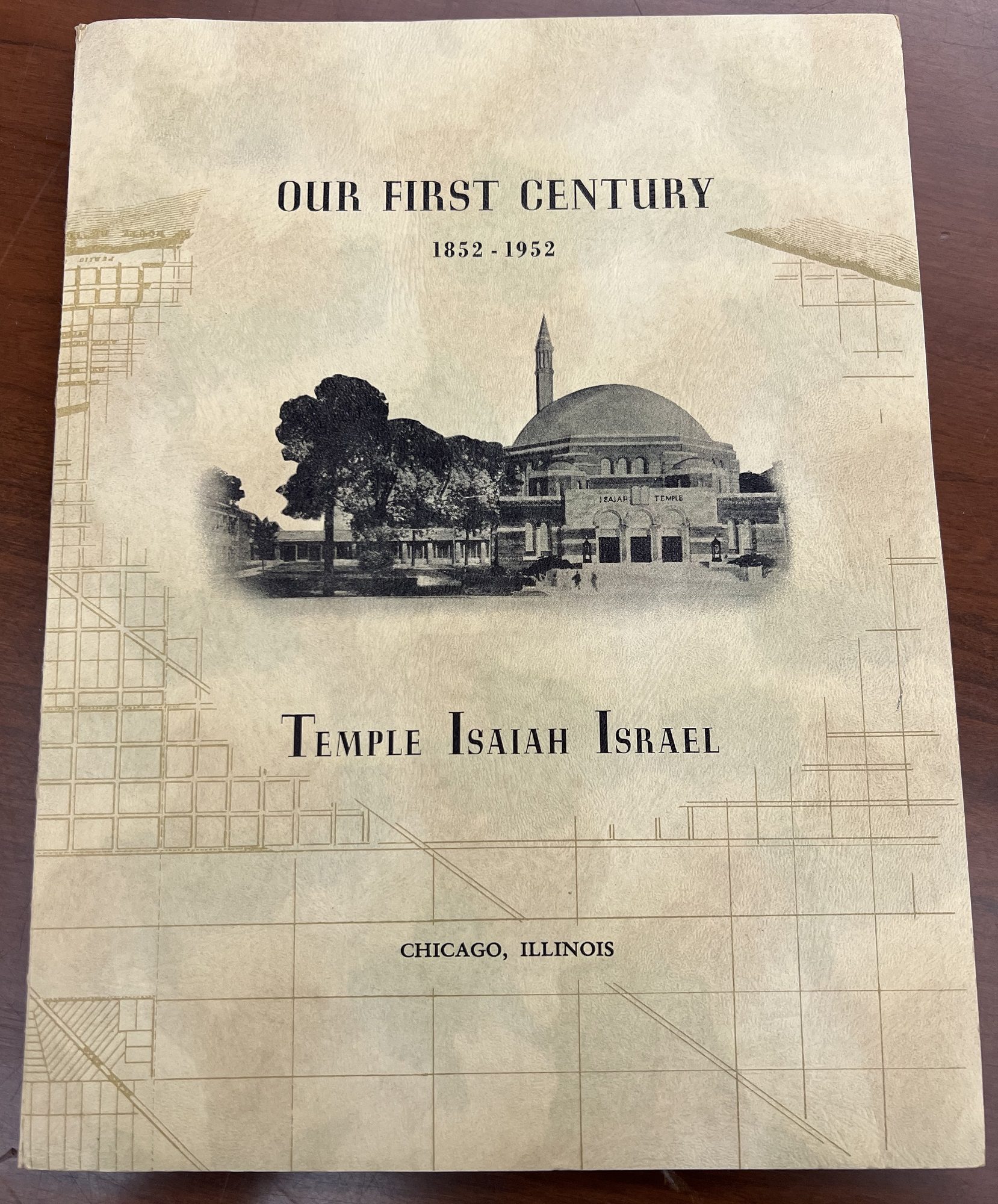

Commemorative book written by Rabbi M. M. Berman at the centennial celebration of Temple Isaiah Israel (B’nai Sholom), 1952. CHM Research Collection, F38W .Y-I7 1952 OVERSIZE

Temple Isaiah Israel’s congregational history demonstrates some of the many shifts, changes, mergers, and migrations that have defined Chicago’s Jewish communities. Jewish migration to Chicago began in the 1830s, with the first permanent Jewish families settling in 1841. The earliest synagogue in Chicago, Kehilath Anshe Maariv (Congregation of the Men of the West) (KAM), was founded in 1847 and led by German Jews who leaned Reform in their form of religious practice.

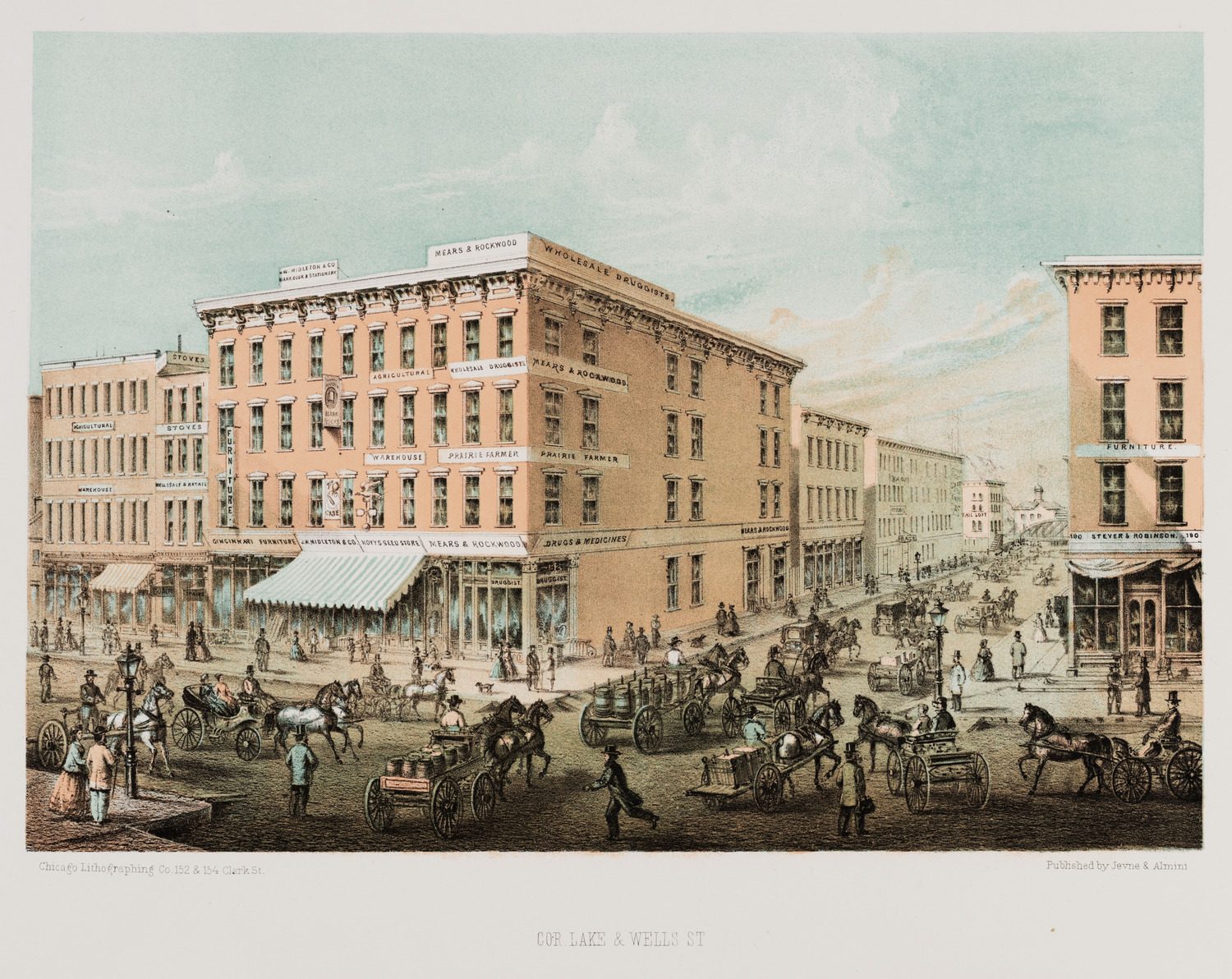

Intersection of Lake and Wells Streets, near the first meeting place for B’nai Sholom, c. 1867; lithograph by Jevne and Almini. CHM, ICHi-040005

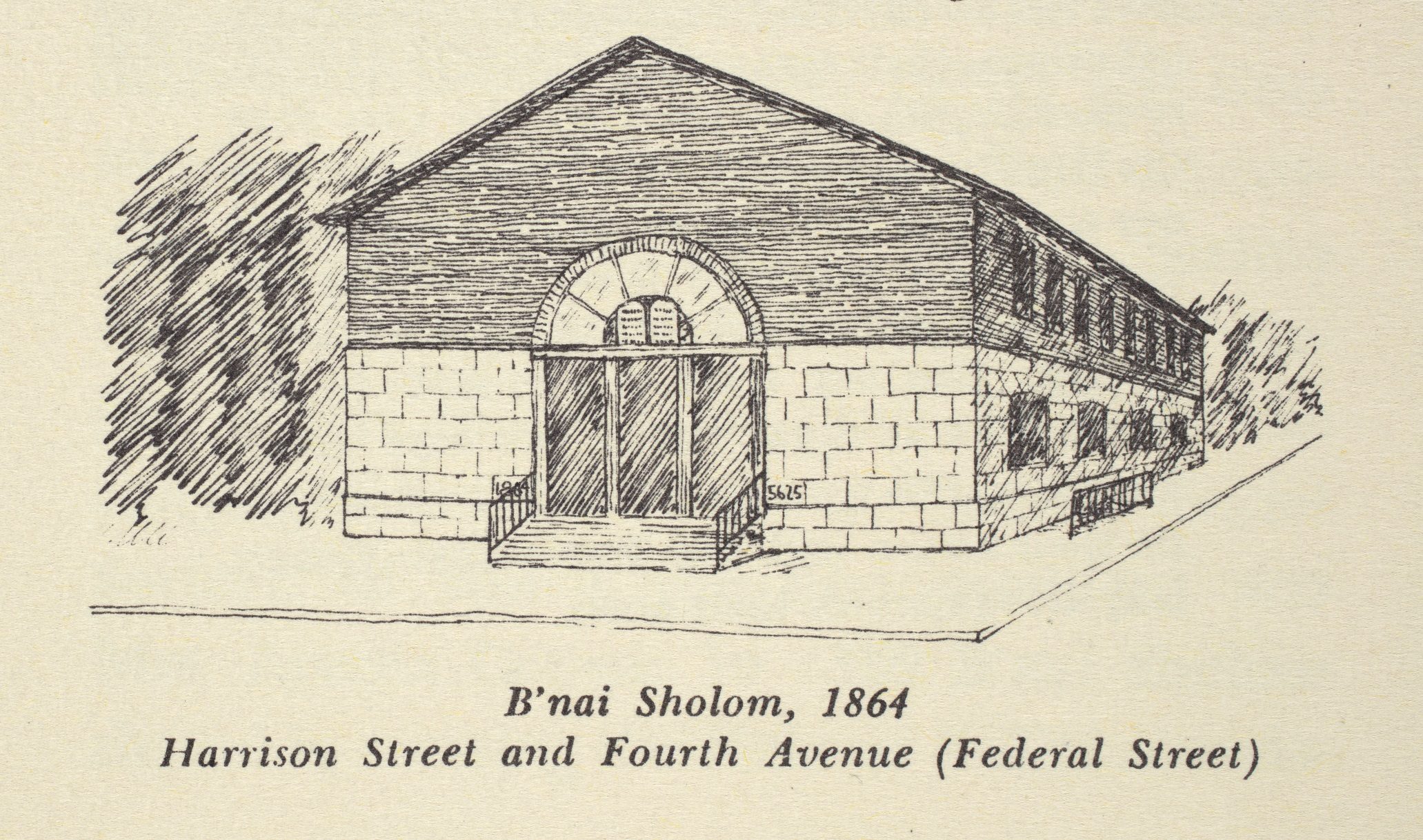

Just five years later, Chicago’s second-oldest congregation was organized by former KAM community members who identified as Polish Jews and leaned more Orthodox in practice. Calling themselves Kehilath B’nai Sholom (Congregation of the Children of Peace), they first met above a clothing store at 189 Lake Street, followed by a couple other temporary locations, before laying the cornerstone of their first building at Harrison Street and Fourth Avenue in 1864.

Architectural drawing of the exterior of B’nai Sholom, 1864. From Our First Century, 1852–1952: Temple Isaiah Israel, the United Congregations of B’nai Sholom, Temple Israel and Isaiah Temple, p. 14. CHM, ICHi-173824A

After losing this building to the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, B’nai Sholom briefly rented a church to hold worship before building a new synagogue on Michigan Avenue between Fourteenth and Fifteenth Streets. Before long, they outgrew this building and moved in 1886 to one formerly owned by KAM.

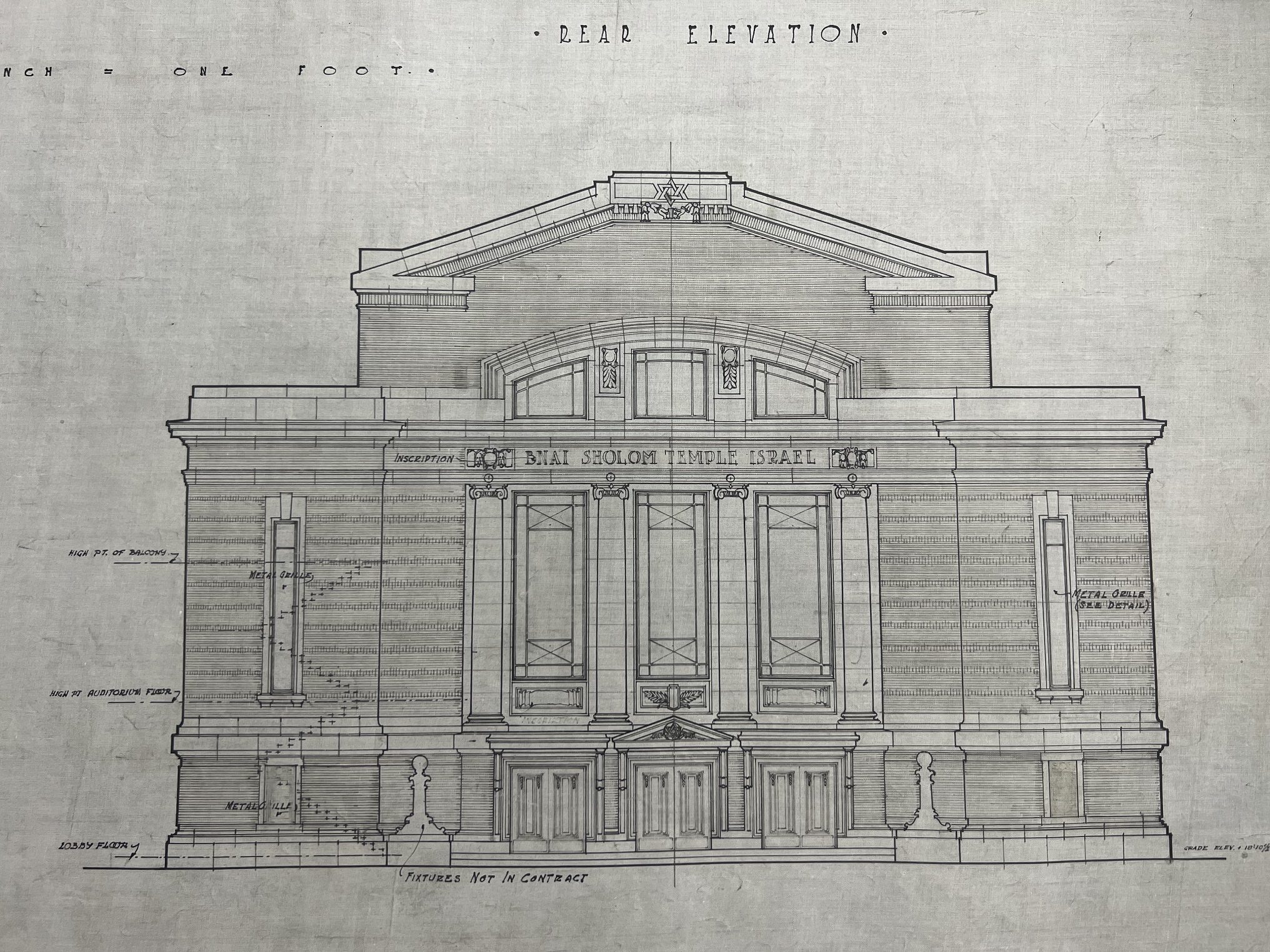

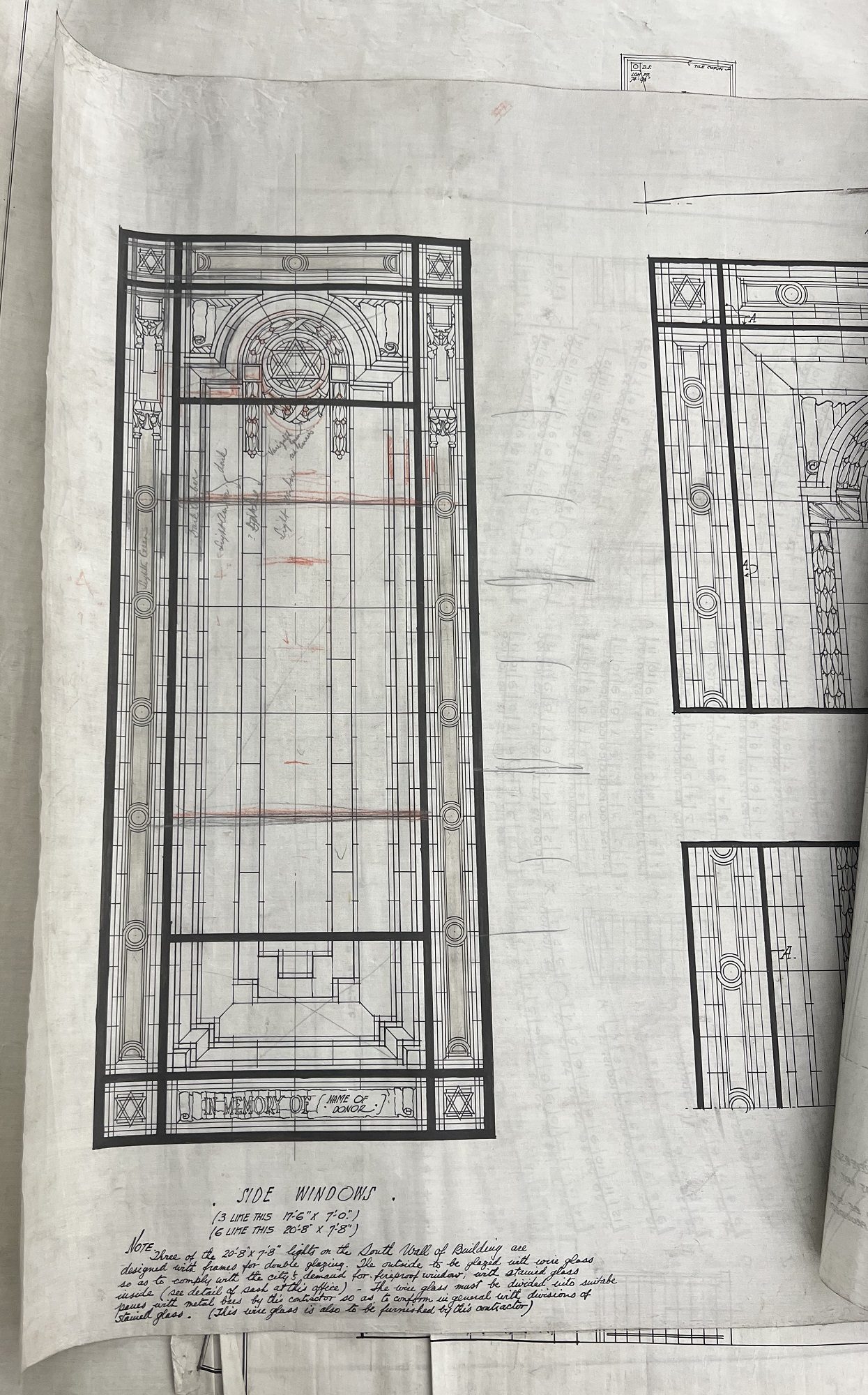

Architectural drawing details for B’nai Sholom Temple Israel by Alfred S. Alschuler, April 1, 1913. CHM collection. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Architectural drawing details for B’nai Sholom Temple Israel by Alfred S. Alschuler, April 1, 1913. CHM collection. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

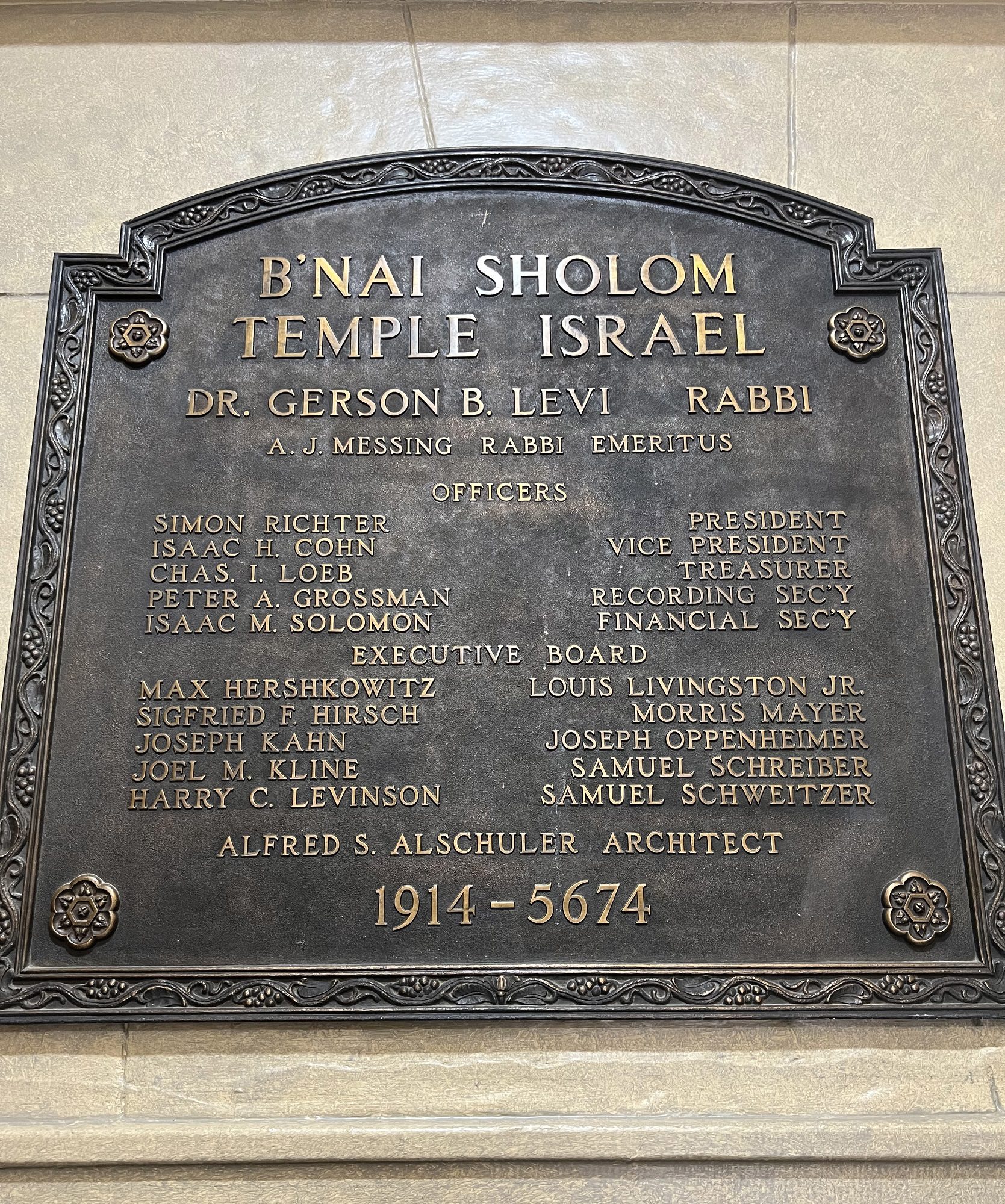

As the wider Jewish community grew, more offshoot congregations were created. Temple Israel (known as the “People’s Synagogue”), branched off from KAM in 1896. A decade later, B’nai Sholom and Temple Israel merged to become B’nai Sholom Temple Israel, originally meeting in Temple Israel’s building at Forty-Fourth and St. Lawrence Streets and later building a new purpose-built synagogue designed by Alfred Alschuler in 1914.

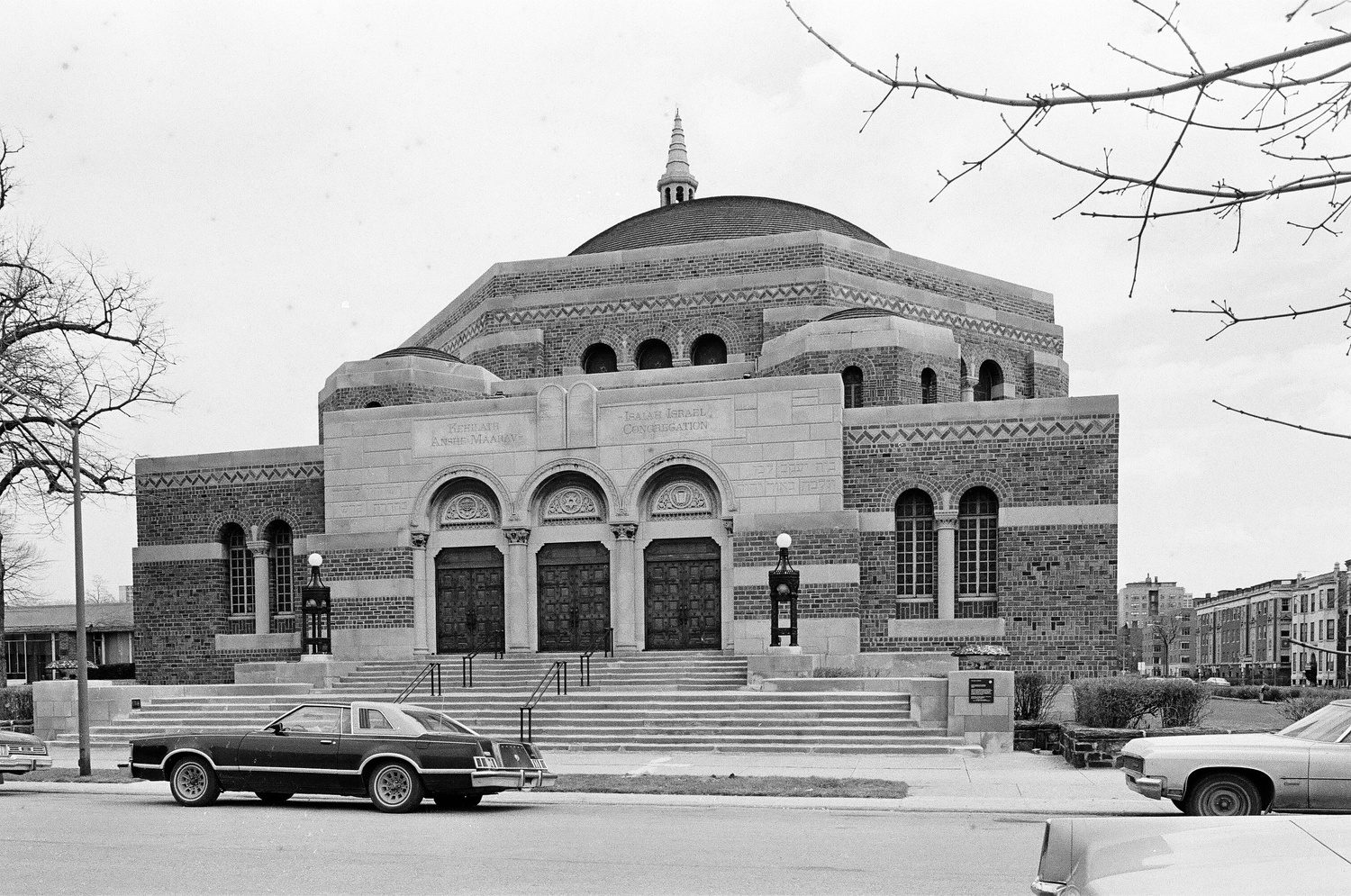

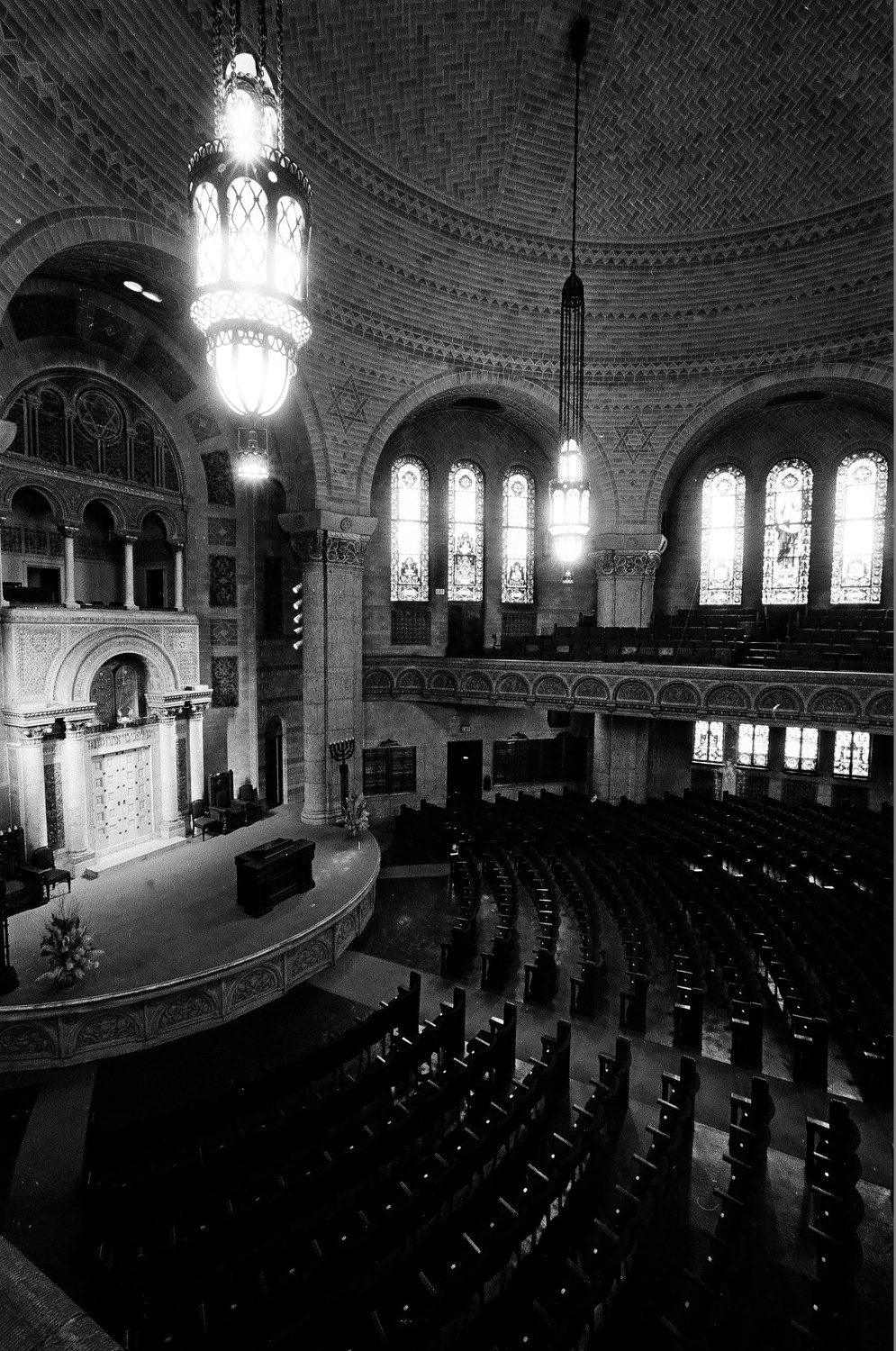

Exterior (top) and interior (below) of Temple KAM Isaiah Israel, 1979. ST-80004699-0024 and ST-80004699-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

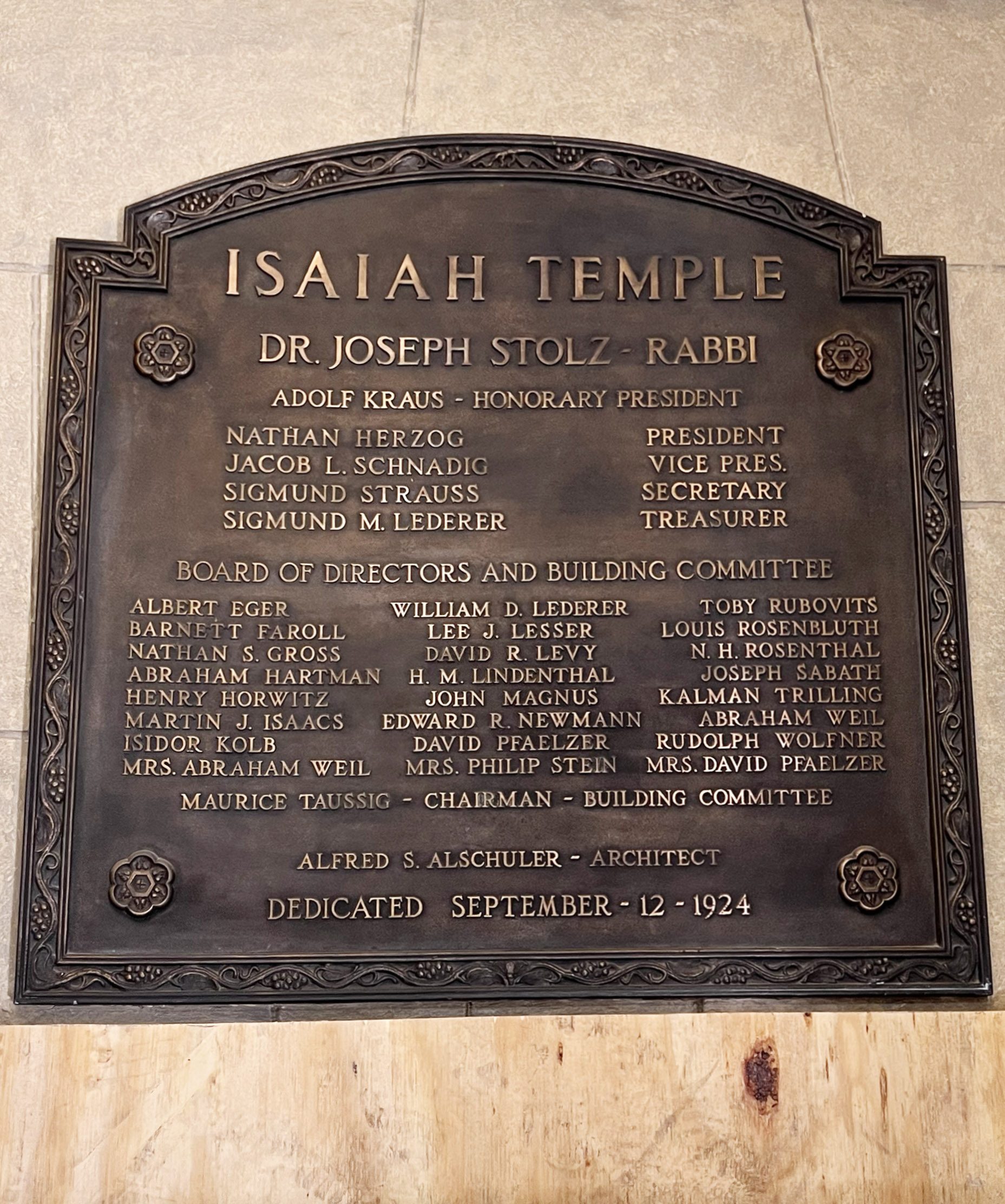

In 1924, further migration and mergers took place with Isaiah Temple, another outgrowth congregation that had formed in 1895. Together, the three congregations became known as Temple Isaiah Israel. The congregation built a stunning neo-byzantine synagogue in the Kenwood neighborhood, also designed by Alschuler.

Memorial plaques inside KAMII from its joining congregations, 2022. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman

In 1971, the congregational mergers came full circle as KAM joined Temple Isaiah Israel to also make Hyde Park Boulevard their home. Today, KAM Isaiah Israel (KAMII) is still an active, thriving congregation celebrating 175 years of presence in Chicago.

KAMII, exterior (top) and interior (below), 2022. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman

Additional Resources

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Chicago’s Jewish community

- See more of architect Alfred Alschuler’s work

- Read the Chicago History magazine article “Welcoming Jewish Americans” on the history of Chicago Hebrew Institute