Elena Gonzales joined the Chicago History Museum in spring 2021 as a guest curator and began as the Curator of Civic Engagement and Social Justice in October 2022. In this blog post, she talks about her work at CHM and how she approaches it.

Elena Gonzales. Image credit: Ben Gonzales

What led you to the Chicago History Museum?

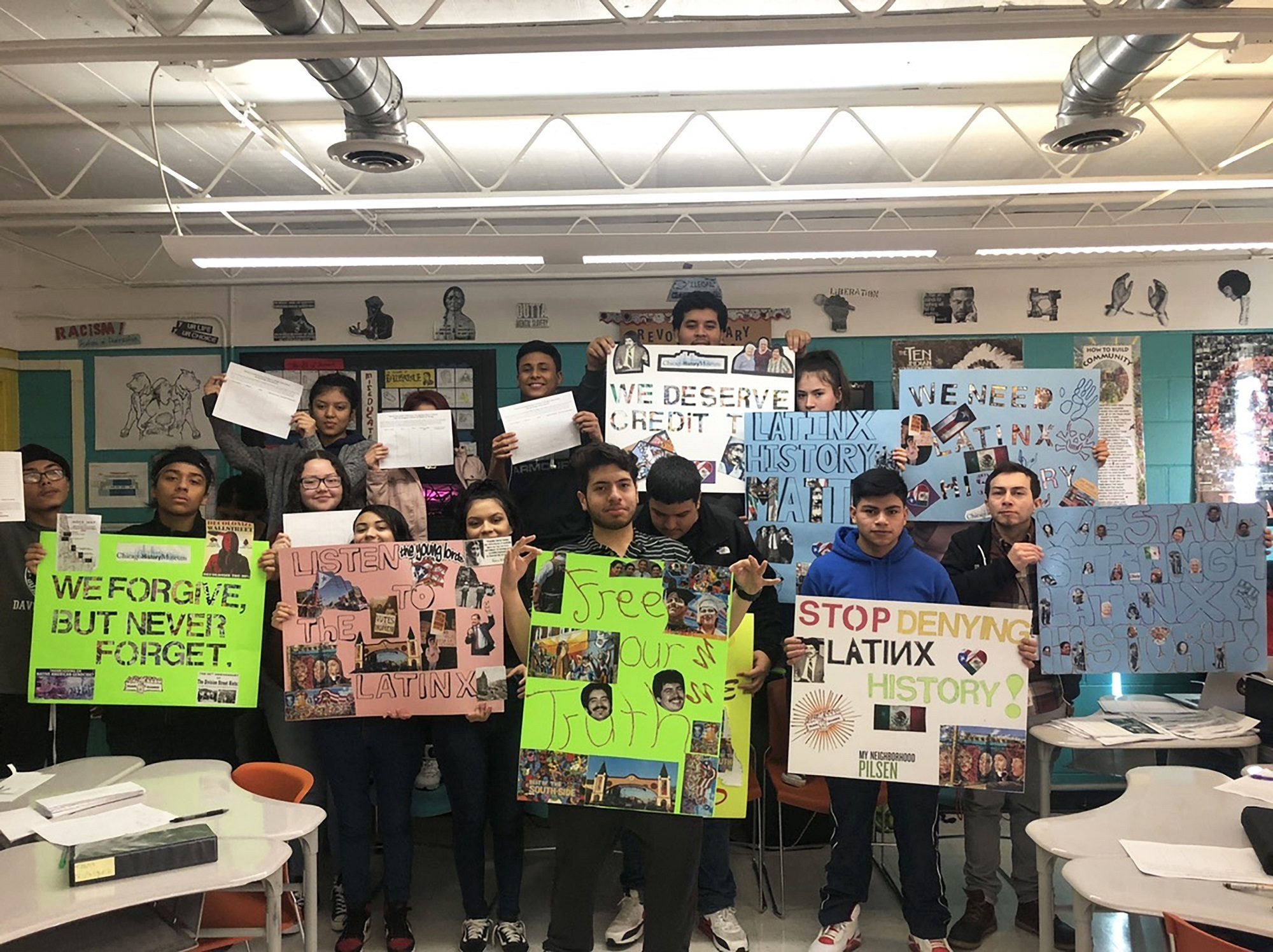

The Museum reached out to me in spring of 2021 to ask if I would curate an exhibition about Chicago’s Latino/a/x communities. In particular, the project was a response to the protest by high school students from Rudy Lozano Leadership Academy / Instituto Justice and Leadership Academy in 2019.

Photograph by Anton Miglietta, History Teacher, IJLA; Courtesy of IJLA and students / alumni.

I had studied and written about CHM relatively extensively at that point, first for my dissertation and later for my book, Exhibitions for Social Justice. To be totally frank, this research left me a little nervous about undertaking the project because I wasn’t sure if the Museum was ready to make the kinds of changes the students were requesting. I’m excited to say that I think we are on that path now.

Your position is Curator of Civic Engagement and Social Justice. How exactly does one go about curating these things? Especially social justice.

The word “curate” comes from a Latin word, “curare,” meaning “to care for.” My work is about caring for people and their stories as well as caring for our society and how well it works for everyone—caring about our collectivity.

My position works in two directions. On the one hand, I am responsible for understanding and employing the Museum’s collections that address civic engagement and social justice in storytelling through exhibitions. Primarily, this is through the Archives & Manuscripts and Prints & Photographs collections with a secondary focus on the Decorative and Industrial Arts collection. On the other hand, it is my job to look for ways that the institution itself can foster civic engagement and work for social justice.

What does a typical day look like for you?

I do a lot of different things as part of my job! They range from research in a library, archive, or special collection to meetings with community members all over town in different neighborhoods and suburbs. On a given day, I could be meeting with a group of paleteros in Albany Park, a scholar in Pilsen, the Little Village Chamber of Commerce, or a family of bomba artists in Humboldt Park. I might be at the Back of the Yards library or researching steel mills in Calumet. These meetings might be about planning collaborations, collecting or borrowing material, or reaching out to additional communities and organizations. I spend two days a week at the Museum exploring the collections, planning and collaborating with colleagues from across the Museum, writing, and so on.

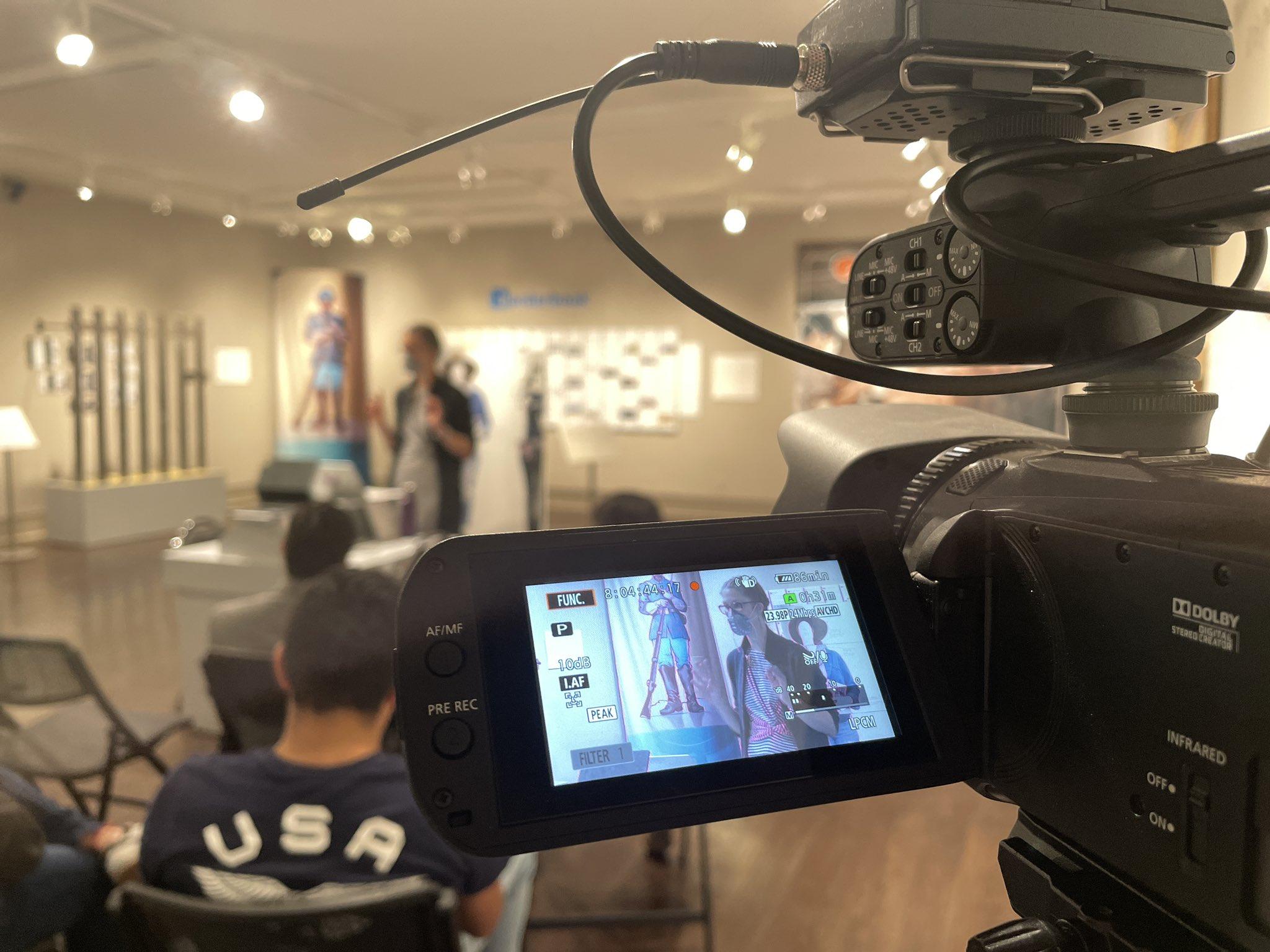

Elena guest teaching at the University of Texas at El Paso’s Centennial Museum in the Pasos Ajenos: Social Justice and Inequalities in the Borderlands exhibition. Photograph by and courtesy of Daniel Aguilera.

You’re leading the charge in curating the Aquí en Chicago exhibition for the Museum, slated to open in 2025. What has that experience been like for you so far?

So exciting! It’s a daunting job to make something about Latino/a/x communities in the area when that population has been absent from the stories at CHM for so long. That makes it feel like there is a lot of pressure for the exhibition to be many different things to different people. This third of the city is so diverse! However, I’ve received a lot of support, both from colleagues at CHM and from Latino/a/x folks of many different backgrounds. We need to keep a focus on the young folks who brought us into this project in the first place. When we center their story—as this exhibition will—the landscape around their story becomes clear. That’s how we got to the focus on resistance against white supremacy and colonialism (in all its many forms). So far, working on this project has been a wonderful experience. It’s a tremendous challenge and so rewarding. One partner at a community-based organization said the nicest thing when she learned we were planning the exhibition for fall 2025. I’m used to people wanting to hear more about why the timeline is so long (trust building and relationship building take time), but what she said was “I feel so safe.” Her words have stayed with me, and I hope to live up to them.

Is there a particular artifact or collection in the Museum that is your favorite or one that has had the most impact in your work so far?

Though it is by no means my favorite, there is an object that I’m kind of obsessed with. It’s offensive not only in its expansionist, colonial stance but also in its butchery of Spanish. It opens a window onto a whole part of the story landscape that is crucial and difficult to access and highlight. The object is called “The American Hen.”

Milk glass bowl with lid, c. 1898. 1973.23a-b. Photograph by Elena Gonzales.

It’s a mass-produced covered dish of milk glass about the size of a butter dish—though it may have been used to hold a condiment such as mustard. Westmoreland Specialty Co. produced it around 1898, likely as a novelty. This was a time when the US doing significant colonization in Latin America. In 1898, the US took over Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, and Cuba—though the US was unable to retain control of the last. “The American Hen” takes the form of a (presumably American) eagle sitting on its nest, its wings outstretched around three eggs labeled “Porto Rica [sic],” “Cuba,” and “Philippines.” It is one of the few objects I’ve found so far that will allow us to have the necessary conversation in the gallery about how US military and economic intervention in virtually every Latin American country has directly influenced the Latino/a/x landscape we live with today in Chicago.

Additional Resources

- Learn more about Elena

- Follow her on Twitter @curatoriologist

See what others are saying!