“What is strange to us today will be familiar to us tomorrow.”—Mayor Richard J. Daley

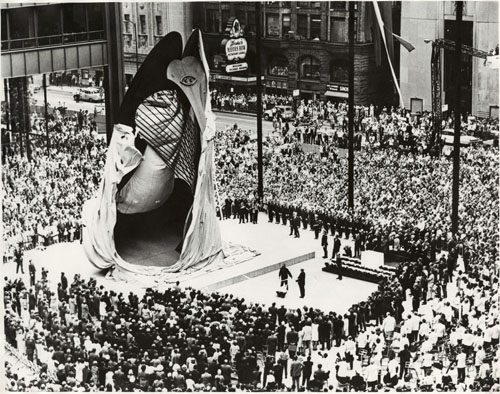

On this day in 1967 at 11:00 a.m., about 50,000 Chicagoans gathered in Civic Center Plaza, now Richard J. Daley Plaza, for the dedication of the first public art work commissioned by the city. Its story, as stated in the ceremony pamphlet, is “a dramatic illustration of the atmosphere and the spirit which drew this artist and this city together.”

The unveiling of the Picasso sculpture on August 15, 1967. Photograph by the Chicago Daily News, CHM, ICHi-092975

In 1963, the Public Building Commission of Chicago decided to build a new Civic Center and adjoining plaza in the Loop. To include a fountain in the plaza was a given, but to include a sculpture was trickier. In the Chicago Architects Oral History Project, William Hartmann, a partner at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, one of the supervising firms, opined, “Public art is difficult. Unless you do it right.” A monumental project such as this one required the appropriate artist, and the architects’ decision was unanimous: Pablo Picasso. Hartmann relayed their choice to Mayor Daley, who remarked, “Well, I don’t know Mr. Picasso, but if he’s the best person in the world, why don’t you go ahead and try?”

Hartmann then set out to contact a man whom he didn’t know and had never visited Chicago to ask him to create something to complement a nonexistent building. Through Allan McNab, the director of the Art Institute of Chicago, he first contacted Sir Roland Penrose, an English biographer of Picasso, who agreed to help. He suggested that Hartmann plan a visit to the south of France and let Picasso know they’d like to drop by. “You see,” Hartmann said, “You don’t just make an appointment with Picasso.”

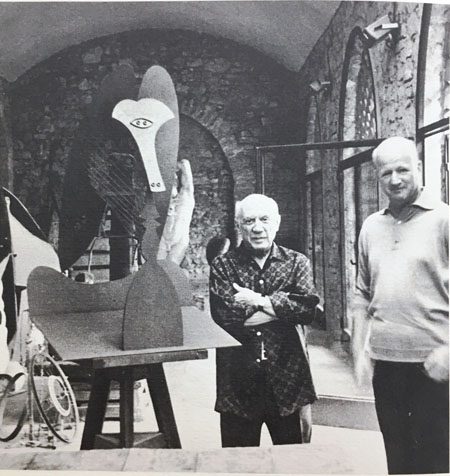

Picasso and Hartmann with the maquette in the artist’s Mougins studio, August 1966. Image from the 1967 program pamphlet

Picasso agreed to see them, and Hartmann sought to acquaint the artist with the project: he brought photographs of Chicago, the site, and its citizens. Hartmann even included photographs of Picasso’s works owned by Chicagoans and local museums to show their recognition of and appreciation for him.

Picasso said he would think about it.

Over the next few years, Hartmann continued to visit and bring Chicago-related items, such a White Sox blazer and a Cubs hat, and updates on the project. Finally, Picasso produced a draft. Hartmann told him, “We want to commission you . . . and end up with a study I can take back.” But Picasso, who refused to discuss business, said, “You know I may not produce anything. [or] I may produce something that you don’t like . . . It’s best that we keep this low-key all the way through, keep it calm and relatively confidential.” So they did.

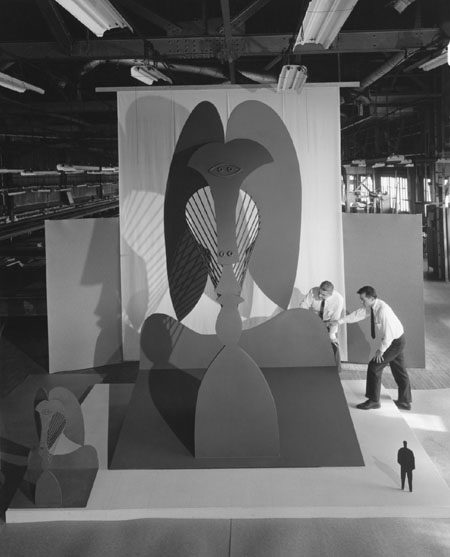

The maquette in a warehouse, 1966. CHM, Hedrich-Blessing Collection, HB-29086-F2

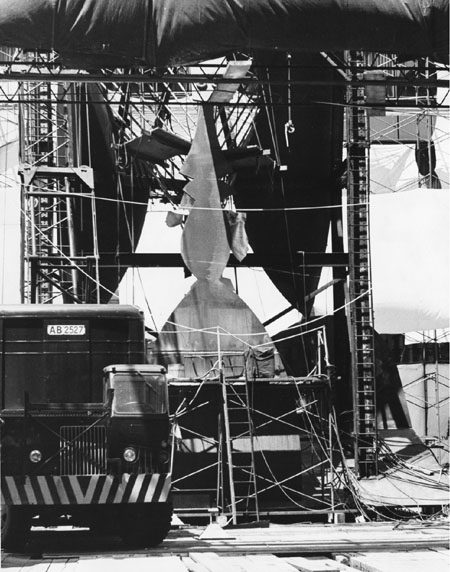

In 1965, the final design was presented to the Public Building Commission, who hemmed and hawed until Mayor Daley walked in and declared that he liked it. The sculpture’s Corrosive Tensile steel pieces were cast by the American Bridge Company in Gary, Indiana, where they were assembled, disassembled, and then transported to Chicago for reconstruction.

The 50-feet tall, 162-ton sculpture being assembled in Civic Center Plaza, July 1967. Photograph by Carol Sincak, CHM, ICHi-067543

Hartmann planned a grand dedication ceremony, which included poet Gwendolyn Brooks and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. When Mayor Daley removed the veil, the crowd gasped and spouted forth amusing commentary, much of which was pejorative. But to Hartmann, this reaction was better than that of indifference: “Picasso’s work, frequently, if not always has been the center of controversy. So it all fit into that pattern beautifully.”

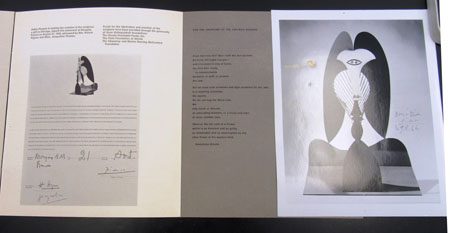

Original dedication program with images of statement and photograph signed by Picasso, 1966, and poem (center) by Gwendolyn Brooks. Photograph by CHM staff

Picasso declined the city’s payment of $100,000, stating that it was his gift to Chicago. The sculpture has since become a gathering place for all and an icon of the city. And while no one can say for sure what the sculpture resembles, it kicked off the city’s fifty year investment in and proliferation of public art.

Join the Discussion