Latest Posts

In this blog post, editor and content manager Heidi Samuelson looks at the 1971 Mayday Protest and anti-Vietnam war actions in Chicago in advance of the opening of Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s–70s.

The Vietnam War sparked a massive antiwar protest movement throughout the United States beginning with demonstrations in the mid-1960s. Chicago became a major center of antiwar activity during this time. Perhaps most notable were the protests prior to and during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. These protests led to a federal investigation, and eight demonstrators (known as the Chicago Eight, later Seven) were famously charged with conspiring to use interstate commerce with intent to incite a riot.

Demonstrators confront the National Guard during Democratic National Convention, Chicago, August 1968. ST-17100140-0003, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

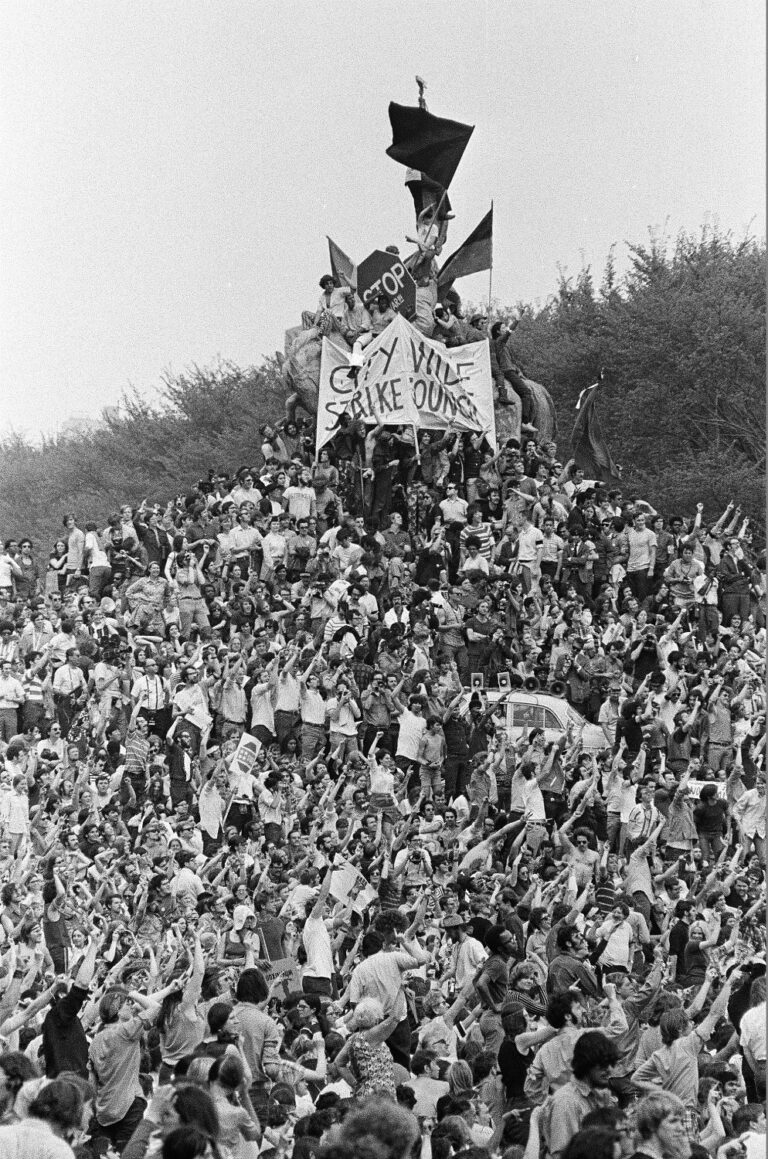

Although one of the leading student activist groups that focused on antiwar actions, the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), had split by 1969, the antiwar movement continued into the 1970s. Opposition to the war escalated after the Nixon administration ordered US ground troops to invade Cambodia on April 28, 1970. On May 4, 1970, four students at an anti-Vietnam War rally at Kent State University in Kent, Ohio, were shot and killed by National Guardsmen. The following day in Chicago, thousands of people, primarily university students, filled Grant Park in protest.

Women for Peace gather at the Federal Building, 219 South Dearborn Street, Chicago, before a march begins in protest the Kent State University student deaths and American action in Cambodia. The march began at the Federal Building and ended at the General John A. Logan statue in Grant Park. ST-10003874-0011, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Following the Kent State shootings, students gathered in Grant Park around the John Alexander Logan Monument in protest of the Kent State University shootings and the Vietnam War, ST-14002662-0004, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

A year later in 1971, the activist landscape was fractured, but May 1 still saw the largest act of civil disobedience in US history—as well as the largest mass arrest. Known as the Mayday Protest, the plan was, simply, to shut down the federal government. Under the slogan “If the government won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government,” organizers detailed in advance 21 bridges and traffic circles in Washington, DC, for protesters to block nonviolently with vehicles, makeshift barricades, or their bodies. The immediate goal was to prevent government employees from getting to their jobs, but the larger aim was, as stated in the Mayday Tactical Manual, “to create the spectre of social chaos while maintaining the support or at least toleration of the broad masses of American people.”

Rennie Davis celebrating release of Chicago Seven at Harper Court Restaurant, Chicago, 1969. Photographed for essay in Scanlan’s Magazine. CHM, ICHi-175702; Stephen Deutch, photographer

One of the organizers of the action was Rennie Davis, one of the Chicago Seven, who took the idea of a nonviolent blockade from a failed attempt of the Brooklyn Chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to stop traffic on the opening day of the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Unlike many organized actions, the Mayday Protest had a decentralized structure. Rather than taking orders from leaders, tactics were shared among different “regions” of the planned action and were followed by small affinity groups.

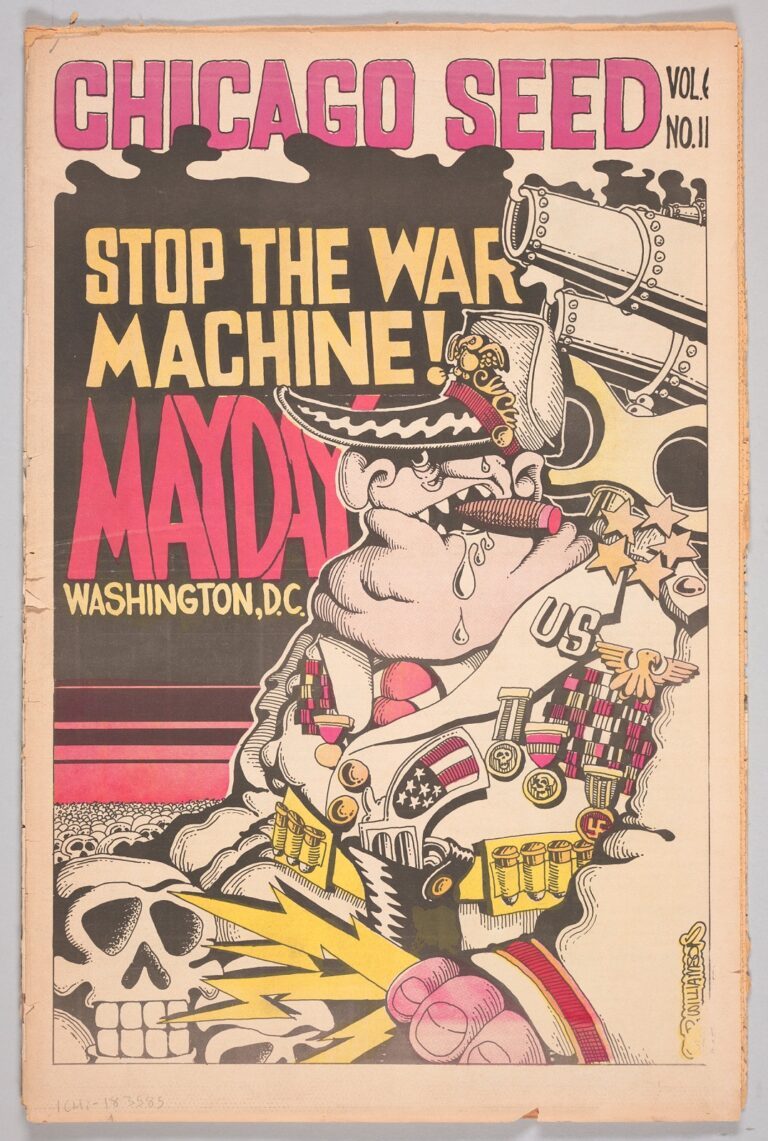

The protest was supported by the Chicago Seed. Established as a collective in 1967, the Seed started as a newspaper about local counterculture. But police action at the 1968 Democratic National Convention radicalized the staff, and they began to focus on more serious issues, particularly the Vietnam War. At its height, the Chicago Seed, which could be purchased for 35 cents at newsstands, reached 30,000–40,000 readers, making it one of the nation’s most widely circulated and influential underground newspapers before it ceased operations in 1974.

The cover of Chicago Seed, vol. 6, no. 11, “Stop the War Machine” by the underground cartoonist Mervyn “Skip” Williamson, was designed to rally support for the 1971 Mayday Protests in Washington, DC. CHM, ICHi-183585; Skip Williamson, artist

Ultimately, the Mayday Protests weren’t widely considered a success. Many of the planned blockades only held for a short time, and in some cases, protesters were arrested en masse before they even got to the blockades. However, the sheer size of the action did send a message to the Nixon administration, which, according to CIA director Richard Helms (quoted in Tom Wells’s The War Within: America’s Battle over Vietnam) was “one of the things that was putting increasing pressure on the administration to try and find some way to get out of the war.”

Additional Resources

- Chicago: Law and Disorder online exhibition

- 1968 Oral History Project: “I Was There”

- The Chicago 7 Trial blog post

- “The Whole World is Watching” blog post

To mark National Day of Puppetry, CHM research center associate Annika Kohrt writes about the mother-son duo of Esther and Ernest Wolff, who established Chicago’s puppet opera scene in the 1930s.

Chicagoans in the first half of the 20th century loved to miniaturize things. From Narcissa Niblack Thorne’s Miniature Rooms to Frances Glessner Lee’s Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, Chicagoans were using miniaturization to relate to the burgeoning city and modernizing world around them. Even the Chicago History Museum was making miniatures in the 1930s: our seven dioramas illustrating Chicago’s history are the longest-displayed artifacts at the Museum.

The city’s arts and performance scene also saw a particularly delightful miniaturization: Puppet. Opera.

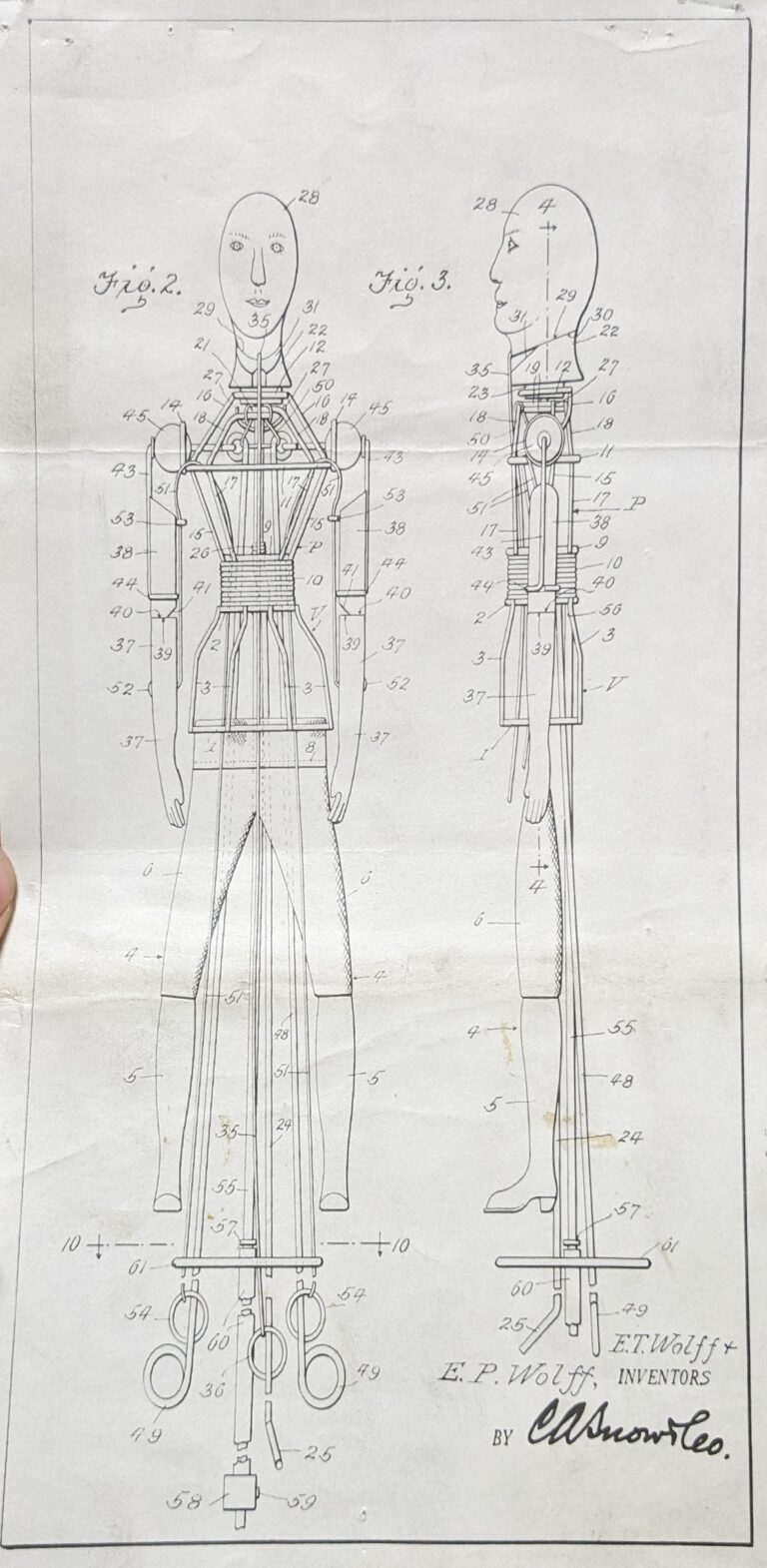

In 1932, the Great Depression bankrupted the Civic Opera Company, and the Lyric Opera didn’t begin operations until 1952. Filling that twenty-year gap with magic and playfulness was a company with a handful of opera records and a cast of hundreds of puppets, created and operated by Esther Theresa Wolff and her son, Ernest. The duo invented an intricate rod puppet, which was operated by puppeteers on wheeled stools underneath the stage.

(From left) Ernest P. Wolff and Esther T. Wolff patent illustrations, CHM, Chicago Miniature Opera Company records [manuscript], ca. 1930-1971. Box 1. Bib#65102; undecorated wire puppet form constructed by Ernest P. Wolff for the Chicago Miniature Opera Theater, c. 1940, CHM, ICHi-175086; puppet depicting Brünnhilde from the opera Die Walküre; this puppet was included in Ernest P. Wolff’s Chicago Miniature Opera Theater, c. 1940. CHM, ICHi-175101

Victor Puppet Opera Troupe: (left to right) Evonne Moller, director of the ballet; Gretel Foerster; Mrs. E. Theresa Wolff, chief operator and mother of the director; and Roberta Haase, assistant, Chicago, c. 1942. CHM, ICHi-016388

Combining puppets and opera involved the creation of delightful characters along with the Wolffs’ marvelous talents. Mrs. Wolff was a widowed Czechoslovakian mother with a background in stage costuming. She was a huge opera enthusiast. CHM’s collection includes several scrapbooks of her programs and newspaper clippings of live Chicago operas, and later all the performances and reviews of the miniature opera. Well indoctrinated into a love of opera, Ernest was making miniature opera sets in a fruit crate in the family’s basement at age 12.

Clipping from Popular Science article by Arthur Stuart, April 1940; CHM, Chicago Miniature Opera Company records [manuscript], 1930–71. Box 1. Bib#65102

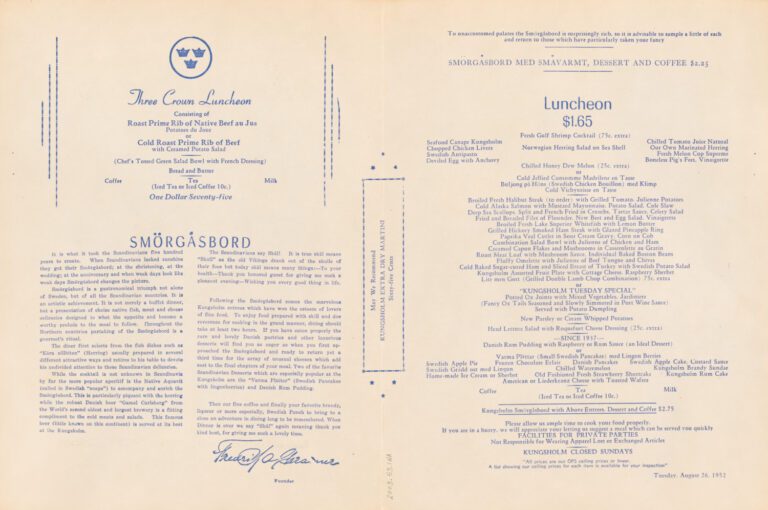

Soon, they were performing full shows around the Midwest to great reviews. The company had a residency at the 1939–1940 New York World’s Fair, where they gained national recognition. After the world’s fair, Ernest decided to serve in World War II. Before he left for Europe, Fredrick Chramer, owner of the Kungsholm Restaurant, saw a puppet performance, and asked to partner. In short order, the puppet opera was permanently installed at the Kungsholm. Fantastical matinees and evening shows were available for children and adults alike, alongside luxurious Scandinavian smörgåsbord dining.

(From left) Kungsholm luncheon menu, July 2, 1952, CHM, ICHi-085972-003; interior view of the lobby of the Kungsholm Miniature Grand Opera, July 18, 1952, HB-15100-C, CHM, Hedrich-Blessing Collection

When Ernest returned to Chicago, it was to a successful puppet opera theater, but it was missing one crucial element: his name. He successfully sued Chramer for not crediting him, then took his settlement, and he and his mother started their own puppet theater once again. He made several TV appearances and had a brief residency at the Hyde Park Hotel, but the theater didn’t take off, and he quit puppetry to go into banking.

Meanwhile, the Kungsholm Miniature Grand Opera was evolving and had become a world-renowned landmark. It was the starting point for two puppeteers: Gary Jones, founder of Blackstreet USA Puppet Theatre, and Bill Fosser, founder of Opera in Focus in Rolling Meadows, Illinois, where you can still see these puppets perform. The Kungsholm puppet opera ultimately closed in 1971. Gary Jones purports that this was partly because of competition from the “real life” Lyric Opera and partly because of declining production quality after the Fred Harvey chain bought the Kungsholm in 1957.

At the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is always free to visit, you can view historic photos, programs, and menus from around Chicago. It’s a real smorgasbord of magic and delight—it might even inspire your next puppet show.

Additional Resources

- Subplot: Memoirs of Chicago’s Kungsholm Miniature Grand Opera

- Luman Coad

- Opera in Focus

- Chicago Miniature Opera Manuscripts

“In seas. In windsweep. They were black and loud.

And not detainable. And not discreet.”

— Gwendolyn Brooks, Riot (Detroit: Broadside Press, 1969)

As the Digital Humanities Curatorial Fellow at CHM charged with developing digital storytelling initiatives using the Museum’s collections items, I face questions about language within metadata (detailed information on an item to help users discover resources) daily. One particularly charged term appearing throughout the digitized collections is “riot.” CHM is currently undergoing a critical analysis of riot terminology within our descriptive metadata—found in the ARCHIE catalog records, CHM Images, and other digital resources used by researchers—with the intention of updating records to represent their historical content more equitably. Language changes, such as the ones for “riot” and “uprising,” fall under the umbrella of CHM’s Critical Cataloging initiatives. This blog post considers Chicago’s “riot” history, the term’s use within the descriptive metadata of digitized collections items at CHM, and best practices for appropriate use and corrective language.

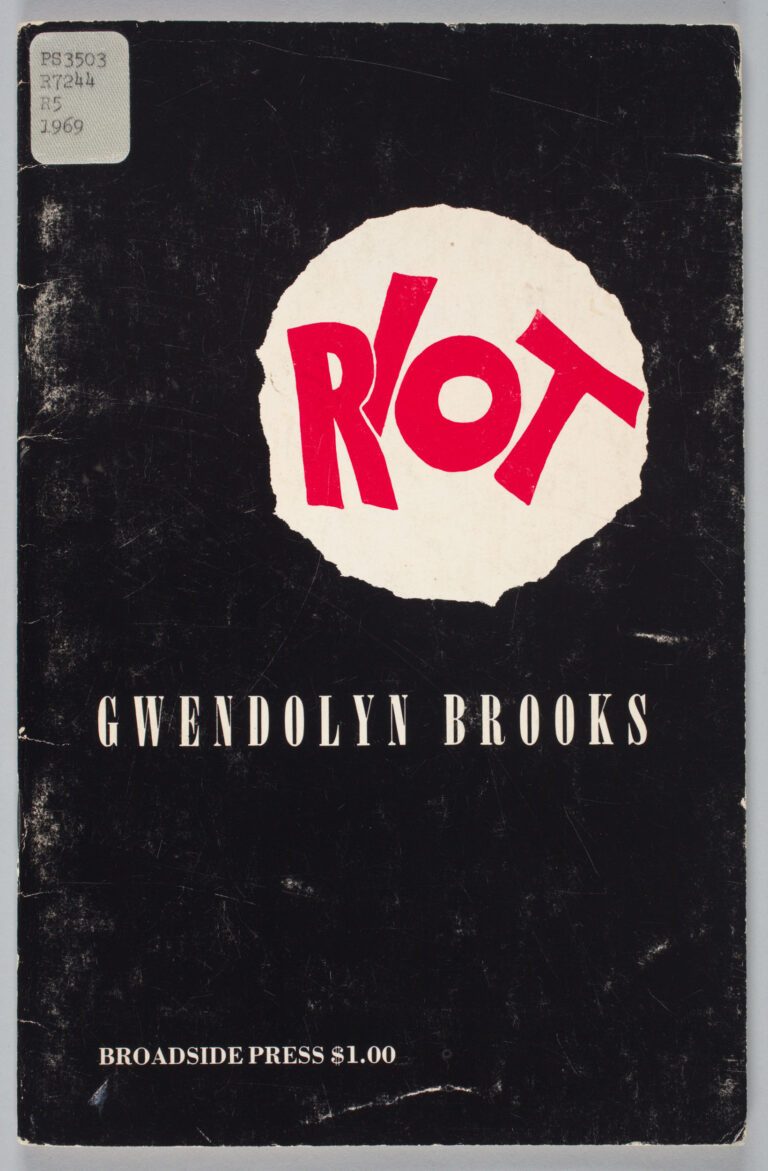

Cover of Riot by Gwendolyn Brooks, 1969. CHM, ICHi-182532b

Perhaps the most iconic usage of the term “riot” is in the title of Gwendolyn Brooks’s three-part poem, published by Broadside Press in January 1969. In Riot, Brooks describes the global Black community’s response to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Brooks’s poem gives meaning to a community “in windsweep,” “black and loud,” as does the frontispiece “Allah Shango” (not pictured) by AfriCOBRA artist collective cofounder Jeff Donaldson. In the painting, two young Black men are shown both trapped behind, and shattering through, a glass window. Brooks’s poetry and Donaldson’s painting depict rioting as a strategy for gaining access to that which has been rendered inaccessible, for giving voice to issues that have been systematically silenced. According to historian Felix M. Padilla, riots follow a pattern: following an influx of population, there are increases in racial violence and legislative acts to prevent movement into white neighborhoods. Overcrowding, disease, police brutality, and violence create the psychological climate for rioting.

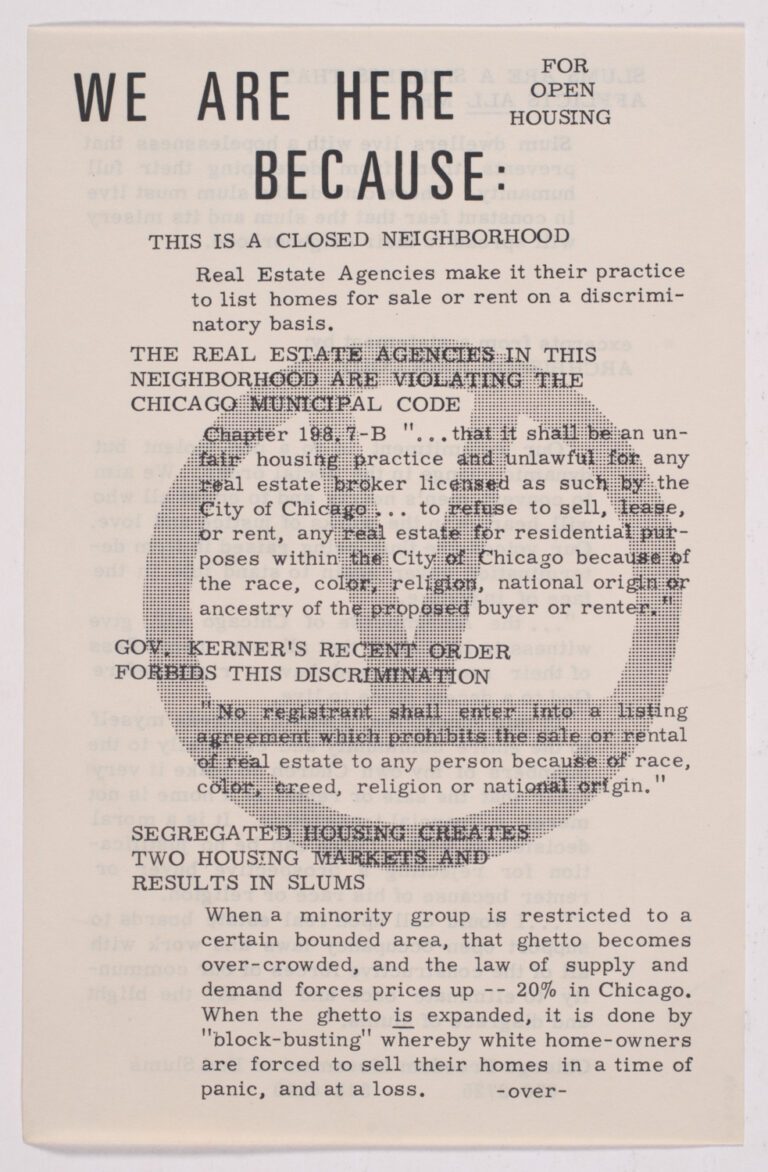

For Black communities of Chicago in the 1960s, this included limited access to adequate housing, health, education, and employment, illuminated by Dr. King when he moved to North Lawndale in 1966 to work with the Chicago Freedom Movement. Visuals created by the Chicago Freedom Movement such as the “MOVE” logo highlight the power of art and design as an agent of protest and advocate for social justice. CHM’s upcoming exhibition, Designing for Change: Protest Art of the 1960s‒70s, explores how Chicagoans used art to advance the Chicago Freedom, Black Power, anti-Vietnam War, women’s liberation, and early LGBTQIA+ movements. Dr. King and the Chicago Freedom Movement used design to visually engage audiences, raise awareness of poor living conditions, and fight against blockbusting, predatory lending, and the dual housing market.

Left: Recto of Chicago Freedom Movement flyer, We Are Here Because, opposing discriminatory real estate practices, Chicago, 1966. CHM, ICHi-183258-001. Right: Cover for the program for the Chicago Freedom Festival with Chicago Freedom Movement symbol on front cover, sponsored by Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations, held at the International Ampitheatre, 4220 South Halsted Street, Chicago, March 12, 1966. CHM, ICHi-182985

Photographs depicting the civil response to King’s murder, known as both the “King Assassination Riots” and “Holy Week Uprising,” speak to the complexities of language. Images of burning and vandalized buildings, shattered storefronts, littered streets, and armed guards inspire visceral responses from their viewers. But as asserted by Darnell Hunt, Dean of Social Sciences and Professor of Sociology and African American studies at UCLA, the terms “rioting” and “looting” connote senseless violence and crime and diminish or obscure the underlying racial oppression and demonstrative purposes of such acts. According to activist Toivo Asheeke, the term riot “holds an inordinate amount of importance on whether one interprets events as justified or not.” Furthermore, the word riot has become a racist trope, according to Dr. Elizabeth Hinton, applied to events properly understood as uprisings or rebellions, that is, collective resistance against an unequal and violent order.

Though sometimes used interchangeably, riot, rebellion, protest, and uprising have been loaded with racial connotations by the media and public throughout history. It is not only who, but how these events are depicted, that generates meaning for viewers. In 2018, previously unsurfaced photographs of the days after King’s assassination taken by Karega Kofi Moyo were displayed at a gallery in the Pilsen neighborhood in the Lower West Side community area. The photographs show a unique perspective of the event compared to the mainstream (white) media publications to date, including an image of a lone young boy covering his face near a group of armed guardsmen in gas masks. Photographs like these illustrate the military-backed violence committed toward the Black community, a tragic and deadly reality of uprisings that is undermined by the term “riot.”

A National Guardsman aims his rifle on West Madison Street during riots following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Chicago, April 6, 1968. ST-17500739-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

When used to describe collective events in Chicago history with distinctive motives and outcomes, the term riot sends conflicting messages. The digitized Chicago Sun-Times collection at CHM, and its descriptive metadata, shed light on this issue. Of the digitized images in this collection, 640 contain the word “riot” in their metadata, and 17 contain the word “uprising.” The term “riot,” often transcribed from the photographer’s original caption, was used to describe the 1919 Chicago Race Riot, the 1966 “Puerto Rican/West Side riots,” the 1977 “Humboldt Park riots,” the 1968 “Democratic Convention riot,” and the 1968 “Martin Luther King Jr. Assassination riots” alike, despite their varied motivations and outcomes. The Chicago Sun-Times collection is part of the archives that CHM is currently studying to specify terminology and correct such conflations.

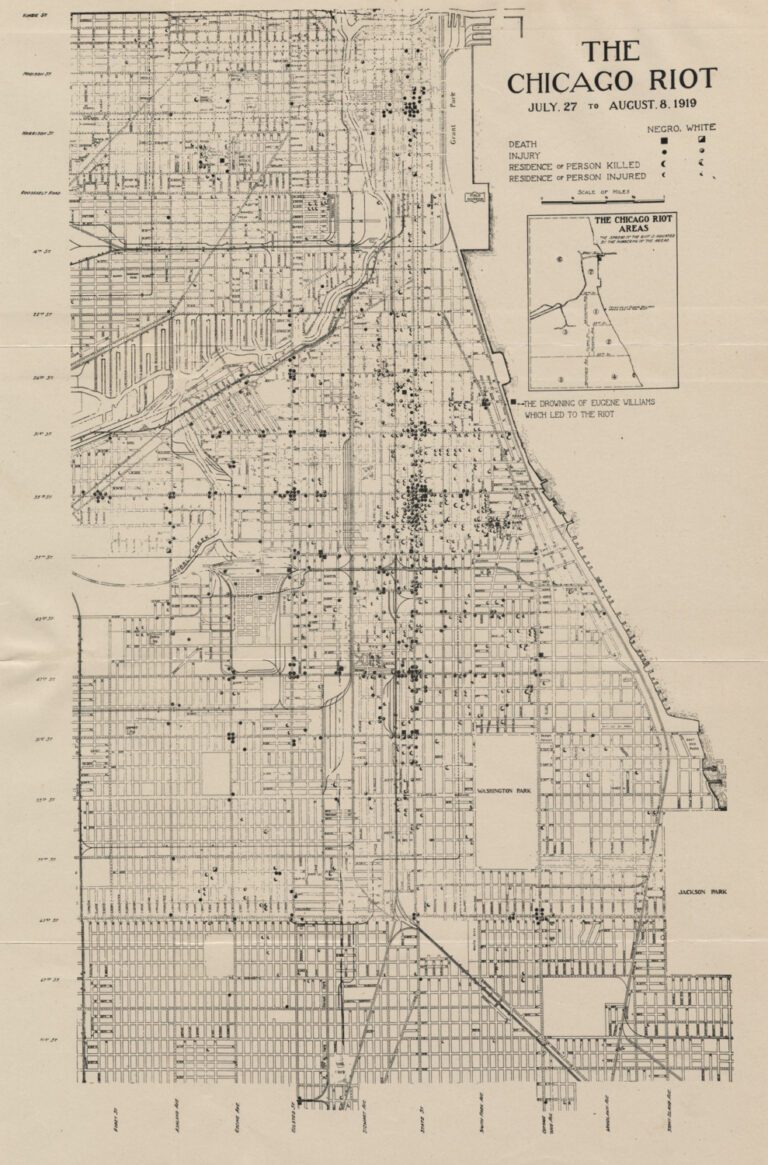

Left: Neighborhood children raiding an African American family’s house after they were forced out during the 1919 Chicago Race Riots, Chicago, 1919. CHM, ICHi-040052; Jun Fujita, photographer. Right: Map of titled The Chicago Riot indicating that most of the fighting occurred between 35th Street and State Street from July 27 to August 8, 1919. CHM, ICHi-040053

In the first half of the twentieth century, riot was frequently used to describe white mobs committing violence against Black people and homes. Following the murder of Eugene Williams by a white mob for floating into a “white” beach, and the violence that erupted into the 1919 Chicago Race Riots, more than 2,800 officers surrounded the Black Belt (a corridor of predominantly Black neighborhoods along State Street), effectively concentrating the violence and its material effects within Chicago’s Black community. Black people were charged with crimes at double the rate as white people, despite suffering two-thirds of casualties resulting from the riot.

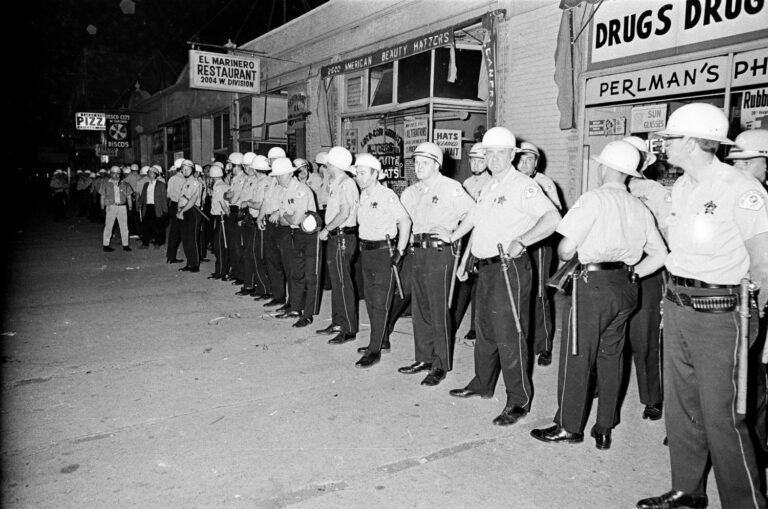

Police presence during riot in Puerto Rican community on Division Street near Hoyne Avenue, Chicago, June 13, 1966. ST-11007177-0006, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

In the 1960s the term riot was applied instead to insurrections against police and institutions, as with the “1966 Puerto Rican/West Side riots.” With the planned redevelopment of Lincoln Park and expansion of DePaul University’s campus in the 1950s and ’60s, Puerto Rican residents were pushed out from their homes and neighborhoods into overcrowded and unsanitary areas to the west. As a response to organized displacement and police brutality against Puerto Rican communities, the 1966 West Side “riots” were motivated by oppression—and therefore, appropriately understood as a “rebellion” or “uprising” distinct from racially-motivated violence like the 1919 Chicago Race Riots.

Members of The Woodlawn Organization (TWO) picket outside of the Polish Roman Catholic Union offices, 984 North Milwaukee Avenue, regarding the desperate need of maintenance work on a 20-unit apartment building in the Woodlawn community area, Chicago, June 11, 1964. ST-10003494-0014, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

As historians, we must be cautious of language used to analyze, marginalize, or mischaracterize the racially discriminated, poor, or disenfranchised, in the past. This includes making distinctions between riot and uprising, one connoting senseless violence, and the other, a collective fight against oppressive systems. Similarly, we must question terms like “ghetto,” “slum,” and “underclass,” which, as with “riot,” have not only been used to describe existing conditions but have contributed to neighborhood disinvestment and decline.

Bibliography

- Paul Bisceglio, “There’s a Difference between Riots and Rebellion,” UCLA Newsroom, July 13, 2015.

- Chicago History Museum. “It Was a Rebellion: Chicago’s Puerto Rican Community in 1966.” Google Arts & Culture.

- Alia E. Dastagir, “’Riots,’ ‘Violence,’ ‘Looting’: Words Matter when Talking about Race and Unrest, Experts Say,” USA Today, May 31, 2020.

- KT Hawbaker, “K. Kofi Moyo Exhibits Scenes of Resistance from Chicago’s Past that Mirror the Present,” Chicago Tribune, August 16, 2018.

- Elizabeth Hinton, America on Fire: The Untold History of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s (New York: Liveright, 2022).

- Ann K. Johnson, Urban Ghetto Riots, 1965–1968 (East European Monographs, 1996), distributed by Columbia University Press.

- Felix M. Padilla, Puerto Rican Chicago (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1987).

- Abigail Perkiss, “The Language of Protest: Race, Rioting, and the Memory of Ferguson,” Yahoo! News, December 3, 2014.

- Ben Railton, “What We Talk About When We Talk About ‘Race Riots,’” Talking Points Memo, November 25, 2014.

- Carl Sandburg, The Chicago Race Riots (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Howe, 1919).

- Jackie Spinner, “Fifty Years after Chicago ‘Riot,’ New Photos Emerge—and Develop a Story,” Columbia Journalism Review, March 7, 2018.

- Heather Ann Thompson, “Urban Uprisings: Riots or Rebellions?” in The Columbia Guide to America in the 1920s (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 109–17.

- William M. Tuttle, “Contested Neighborhoods and Racial Violence: Prelude to the Chicago Riot of 1919,” Journal of Negro History 55, no. 4 (1970): 266–88.

- David Wyatt, “Chicago,” in When America Turned: Reckoning with 1968 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 231–54.

- Heather Yarrish, “White Protests, Black Riots: Racialized Representation in American Media,” Young Scholars in Writing 16 (August 2019): 6–24.

Passover 2024 begins at sundown Monday, April 22, and ends at sundown on Tuesday, April 30. In this blog post, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman writes about the Chicago Loop Synagogue and a Passover Seder shared by its rabbi, Irving Rosenbaum, in 1966.

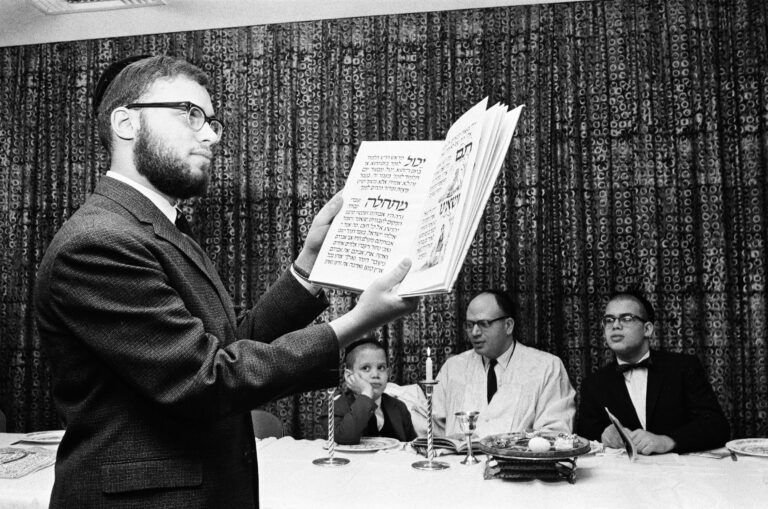

A Seder table with Rabbi Irving Rosenbaum (seated, center) and his sons at Chicago Loop Synagogue, March 31, 1966. ST-11005561-0005, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

This set of images shows a staged Passover meal taking place at the Chicago Loop Synagogue in 1966. Featured center is Roy Rosenbaum (age 19) reading to his father, Rabbi Irving Rosenbaum, and his two brothers, Alan (age 6) and Don (age 15). Roy is holding a Haggadah, a book that details the order of the Passover meal, known as the seder (seder, in fact, means “order”). It outlines stories from the Book of Exodus and includes a series of blessings, songs, actions, and ceremonial foods and drinks as a guide for families and communities through the symbolic meal.

Roy Rosenbaum reads from a Haggadah during a Seder at Chicago Loop Synagogue, March 31, 1966. ST-11005561-0001, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Roy is reading pages from a section in the seder that discusses four sons or four children: the wise, the wicked, the simple-natured, and the one who doesn’t know how to ask. These children represent different ways of approaching and learning about the story of Passover. The Haggadah next shares the Exodus story as a movement from slavery toward freedom. While seders are often something done at home with family, they may also be done in synagogues or in larger community, all with an emphasis of passing the story through the generations and recalling humankind’s search for freedom.

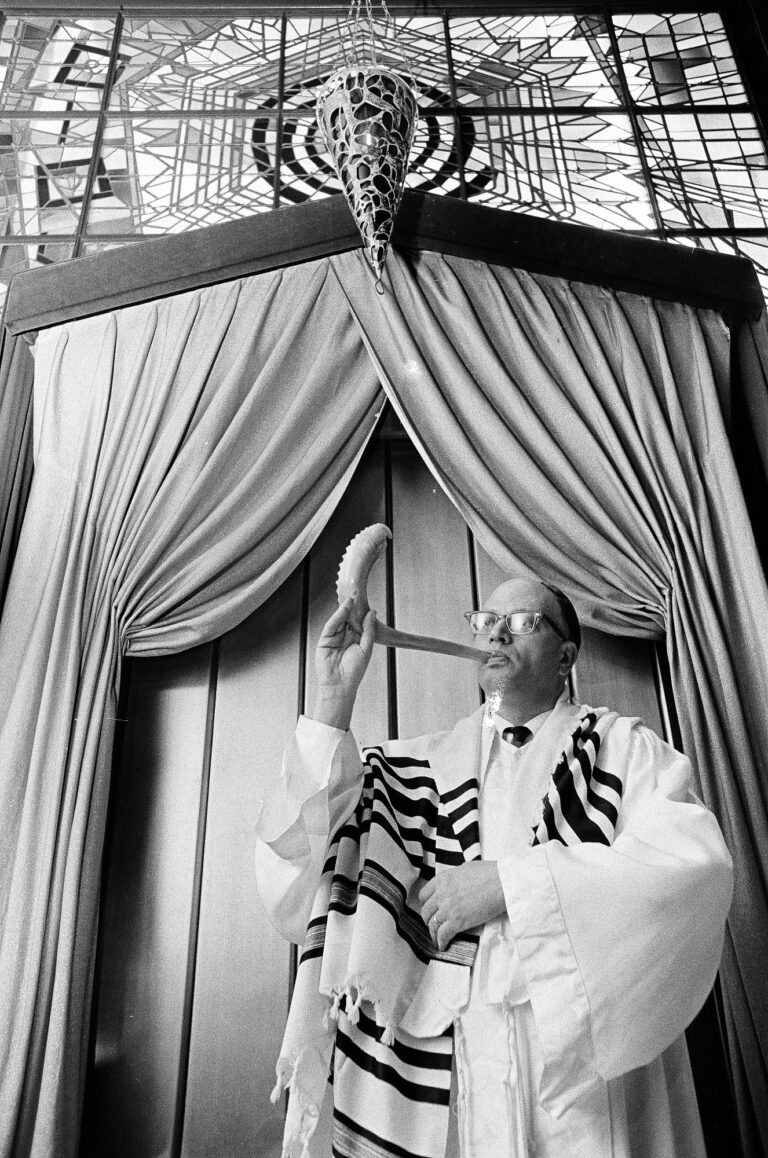

Rabbi Irving J. Rosenbaum blows a shofar during Rosh Hashanah services at the Chicago Loop Synagogue, September 20, 1968. ST-11005551-0007, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Rabbi Irving J. Rosenbaum (c. 1922–2005) served as rabbi of Chicago Loop Synagogue for 14 years. Born in Omaha, Nebraska, Rabbi Rosenbaum moved to the Chicago area for school at age 16. He attended the University of Chicago in Hyde Park and Hebrew Theological College in Skokie, graduating in the 1940s. In 1946, he served as the National Director of the Department of Interreligious Cooperation for the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith. Rabbi Rosenbaum was especially dedicated to education, including in interfaith settings. For example, he produced a film and accompanying booklet for non-Jews called Your Neighbor Celebrates to explain Jewish religious practice and holidays. This fervent interest in religious education was passed down to the next generation, as all three of his sons would go on to also become rabbis.

Chicago Loop Synagogue as seen from Clark Street, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Chicago Loop Synagogue was founded in 1929 to provide a space for Jewish professionals working downtown. The community began by renting different spaces around the Loop for daily and Friday evening (Kiddush) prayers. In the 1950s, they were inspired to construct a purpose-built synagogue after seeing Temple Har Zion in River Forest, Illinois, completed in 1951. They commissioned Har Zion’s architects—Loebl, Schlossman, and Bennet—to design their current building on South Clark Street between Madison and Monroe Streets, completed in 1958.

Today known as Loebl, Schlossman, and Hackl, the synagogue designers’ firm was founded in 1925, with the practice’s name shifting in passing decades as new partners and collaborators joined and left over time. Their founding namesakes, Jerrold Loebl and Norman Schlossman, had grown up in Hyde Park and both studied architecture at Armour Institute of Technology (today Illinois Institute of Technology). Richard M. Bennet, who was originally from Pennsylvania and had studied at Harvard University, joined Loebl and Schlossman in 1947, shifting the practice’s name to Loebl, Schlossman and Bennet for the next two decades until joined by a fourth architect, Edward Dart, in 1965. They designed several impressive synagogues, including Lakeview’s Temple Sholom (1928), but their legacy extends much further through various planned projects and urban renewal schemes, especially in the Bronzeville neighborhood, as well as public housing, suburban developments such as Park Forest, and downtown Chicago’s Richard J. Daley Center.

Left: Women speak to the congregation regarding Soviet Jews at the Chicago Loop Synagogue, December 10, 1979. ST-60002959-0001, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM. Right: Loop Synagogue sanctuary interior, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Loop Synagogue was designed not only to be architecturally and artistically beautiful but also includes layers of symbolic meaning as well as practical design to facilitate Orthodox Jewish needs. Two primary examples of this are in the main worship space. First, in place of an elevator, a long ramp leads between the first and second story to facilitate easy access for congregants unable to use the stairs. Since a traditional elevator uses electricity, its use would be prohibited on Shabbat for Orthodox Jews, so the ramp permits moving between levels while aligning with this prohibition.

Stained glass window by Abraham Rattner in Loop Synagogue’s sanctuary, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Similarly, as lights also usually require electricity, the sanctuary’s east side has an extraordinary stained glass window that runs nearly floor to ceiling. Designed by Abraham Rattner and considered one of the finest windows of its kind, its impressive size also serves a practical purpose by letting in plentiful, colorfully filtered light. The window, called Let There Be Light, is based on the scripture Genesis 1:3 and includes symbolic and literal references to light, including flames as a symbol of Divine presence and a seven-branched Menorah symbolizing inner light.

View of the Ten Commandments in both Hebrew and English at the Chicago Loop Synagogue, May 21, 1969. ST-19042097-0003, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Another beautifully symbolic element sits at the threshold of the building, visible from the street and just inside the synagogue’s entrance doors. A sculpture of the Ten Commandments, both in English and Hebrew, acts as bridge from the outside world to the inside’s sacred space.

Hands of Peace sculpture by Nehemia Azaz above the entrance to Chicago Loop Synagogue, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Religious practice downtown has shifted dramatically in recent years, compounded with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to a significant decline in membership for the synagogue. The synagogue’s community, led by President Lynn Zoldan, continues to think of creative ways to serve their Jewish congregation while welcoming new uses to help preserve the space for the future. Outside the synagogue’s entrance on Clark Street is Nehemia Henri Azaz’s impressive Hands of Peace sculpture, which places the outstretched hands of the priestly benediction said over congregants against a backdrop of its very words in both English and Hebrew, serving as a blessing for those outside passing by.

Further Reading

- Read the entry on Jews in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Read the entry on Judaism in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Read the entry on the Loop in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Read the blog post “Hag Pesach Sameach: Passover and Chicago’s Jewish Communities“

- View the HABS documentation for Chicago Loop Synagogue

Grant funding will support the planning of an upcoming exhibition celebrating Latine history and cultures in Chicago

CHICAGO (April 18, 2024) – The Chicago History Museum (CHM) is thrilled to announce that it has been awarded a grant of $74,000 from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to support its project “Aquí en Chicago.” This grant will facilitate the planning of the dynamic temporary exhibition exploring the rich history and vibrant cultures of the Latine people of Chicago.

With “Aquí en Chicago,” CHM seeks to deepen its commitment to inclusivity and representation and celebrate the persistent cultural presence and significant contributions of Latine Chicagoans to the city’s history. Elena Gonzales, CHM Curator of Civic Engagement & Social Justice, expressed gratitude for the support from NEH, stating, “Thank you, NEH, for supporting the preparation for ‘Aquí en Chicago.’ Again and again, partners and community members have shared how vital they feel it is for the Museum to build its inclusiveness and representation of the Latine third of the city, and NEH is helping us do this crucial work.”

The project will encompass a range of initiatives aimed at celebrating and preserving the cultural heritage of Latine communities in Chicago. This includes the development of a 2,900-square-foot temporary exhibition, scheduled to open in fall 2025, as well as paid research internships, an oral history project and a series of workshops focused on collecting and preserving cultural heritage. Throughout the planning process, the Chicago History Museum is actively collaborating with community organizations to ensure the intersectionality of Latine experiences in Chicago is accurately represented and celebrated.

Veronica Casados, CHM Public Communications Manager, is available for further inquiries or interview requests regarding the project. For more information about “Aquí en Chicago” and the Chicago History Museum, please visit: https://www.chicagohistory.org/aqui-en-chicago/

###

ABOUT THE CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

The Chicago History Museum is situated on ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi people, who cared for the land until forced out by non-Native settlers. Established in 1856, the Museum is located at 1601 N. Clark Street in Lincoln Park, its third location. A major museum and research center for Chicago and U.S. history, the Chicago History Museum strives to be a destination for learning, inspiration, and civic engagement. Through dynamic exhibitions, tours, publications, special events and programming, the Museum connects people to Chicago’s history and to each other. The Museum collects and preserves millions of artifacts, documents, and images to assist in sharing Chicago stories. The Museum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chicago Park District on behalf of the people of Chicago.

ABOUT THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES

Created in 1965 as an independent federal agency, the National Endowment for the Humanities supports research and learning in history, literature, philosophy, and other areas of the humanities by funding selected, peer-reviewed proposals from around the nation. Additional information about the National Endowment for the Humanities and its grant programs is available at: www.neh.gov.

In this blog post, CHM director of research and access Ellen Keith highlights some of the house history resources in the Abakanowicz Research Center.

Are you a Chicago resident who’s curious about the history of your home? If so, come visit the Abakanowicz Research Center! Our librarians are happy to assist you in navigating the resources in our Building and House History Guide.

A castle-like apartment complex at 2556 West Fitch Avenue in the Rogers Park community area, Chicago, July 10, 1975. ST-90003352-0012, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Where to begin?

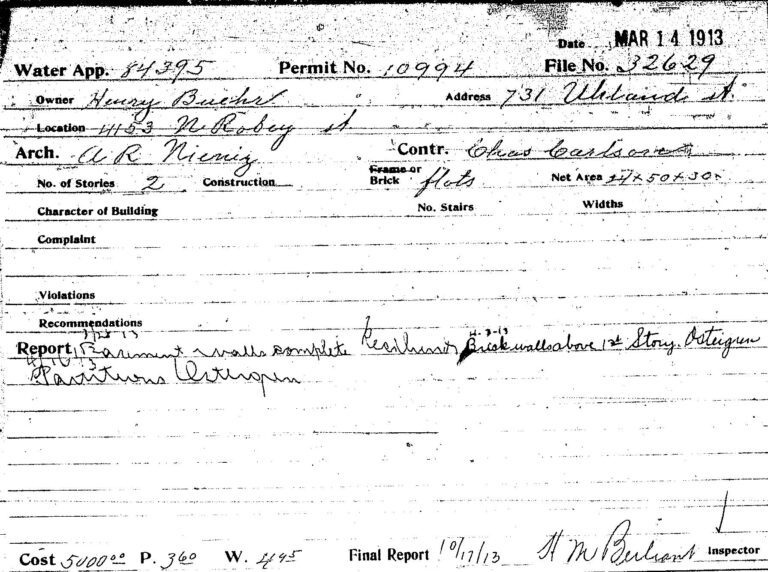

Let’s start with building permits. Often a house history researcher comes in wanting to confirm the date their home was built. We have building permits on microfilm from 1872 to 1954 (think the year after the 1871 Great Chicago Fire to the year before Richard J. Daley was elected mayor). Depending on the year the permit was filed, you can get varying amounts of information. Architects were included on permits after 1912. The University Library of the University of Illinois Chicago has digitized the microfilm.

A building permit ledger entry for 4153 North Robey Street, which is now Damen Avenue, March 14, 1913.

Next, do we have a photograph of your home? We have a large collection of photographs arranged by subject, and the photographs of streets are among the most popular. If you’re interested in a specific area, the Sigmund J. Osty visual materials, approximately 1960–76, are organized by neighborhood.

The 300 block of South Wolcott Avenue, Chicago, February 29, 1964. CHM, ICHi-074046; Sigmund J. Osty, photographer. These buildings do not appear to exist any longer, possible casualties of the Illinois Medical District.

If you’re interested in how your neighborhood has changed over time, a.k.a. the built environment, do we have a resource for you! Fire insurance maps are snapshots of a place in time. They were published to assess risk so the outlines of buildings are color coded with yellow for frame, pink for brick, and blue for stone. Buildings are also labeled with “S” for Store, “D” for Dwelling, and “F” for Flat. Our collection spans from the 19th to the later 20th century (1975 is the most recent). Each numbered volume covers a portion of the city and when there are multiple years for a volume, you can see your neighborhood change over time from a few buildings to a block early on and then in later years, blocks are filled in, and often what were single family homes (dwellings) are now flats (apartment buildings).

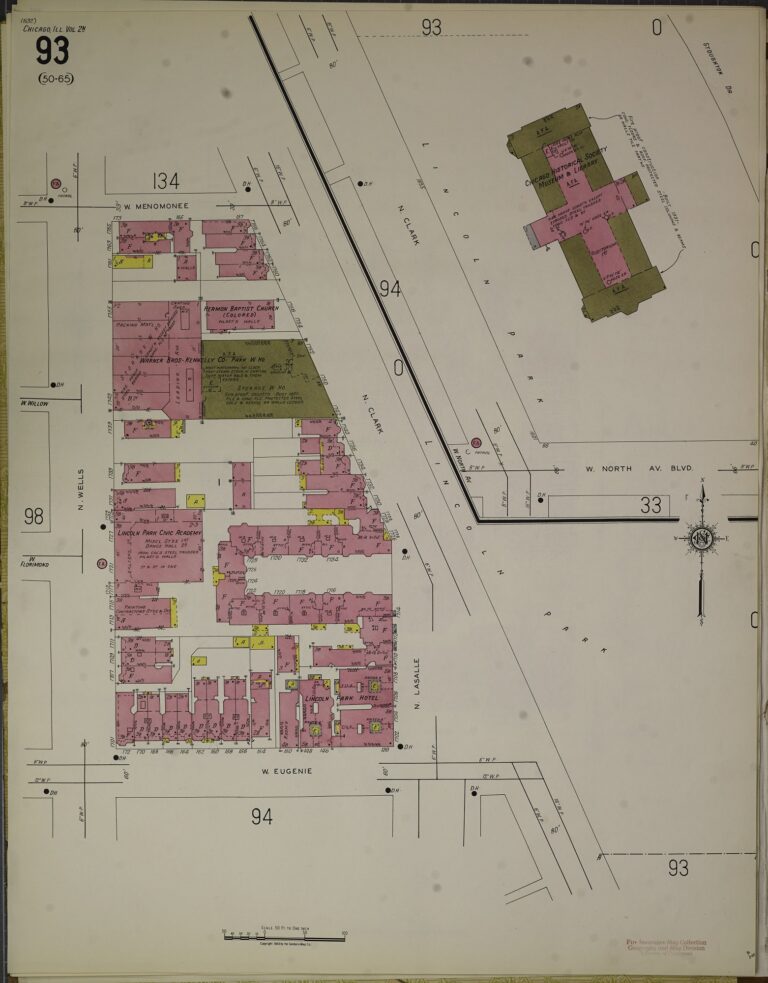

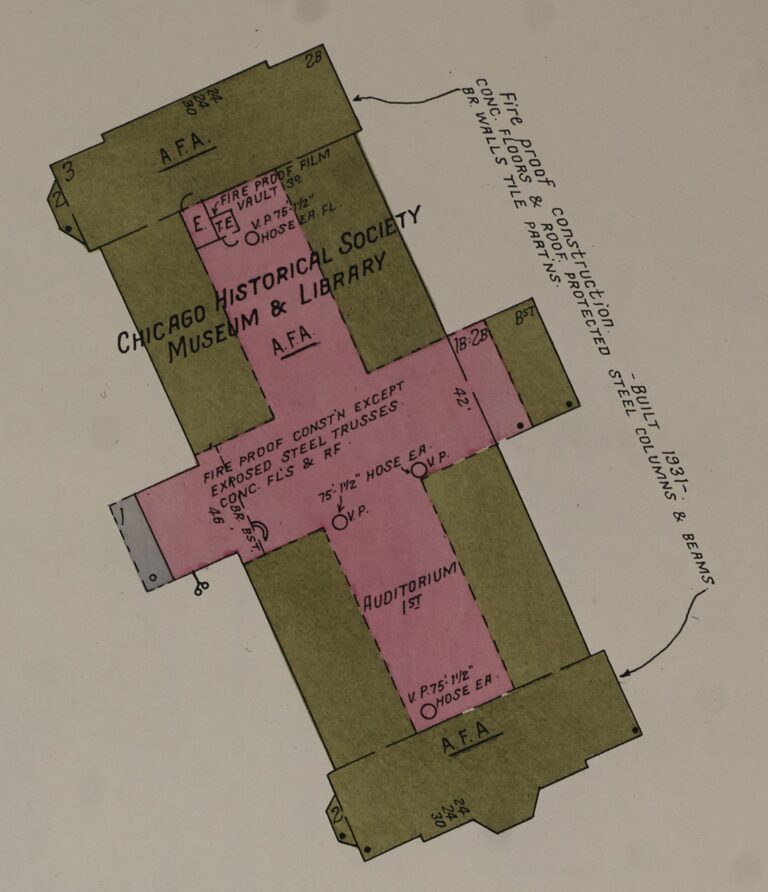

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Chicago, Cook County, Illinois. Sanborn Map Company, Vol. 2, North, 1935. Map. The Chicago History Museum (then the Chicago Historical Society) original 1932 building is in the top right corner.

A close-up view of the “Chicago Historical Society Museum & Library,” which has “fire proof construction.”

Physical fire insurance maps are quite impressive. They’re very large and were expensive to reprint so when a volume was updated, corrections were pasted over the originals, which makes looking at them quite a tactile experience as pages get thicker and thicker with their corrections. If you’re not able to visit, however, there’s an excellent website, Guide to Chicago Sanborns volumes, that links to those freely available through the Library of Congress and the University of Illinois.

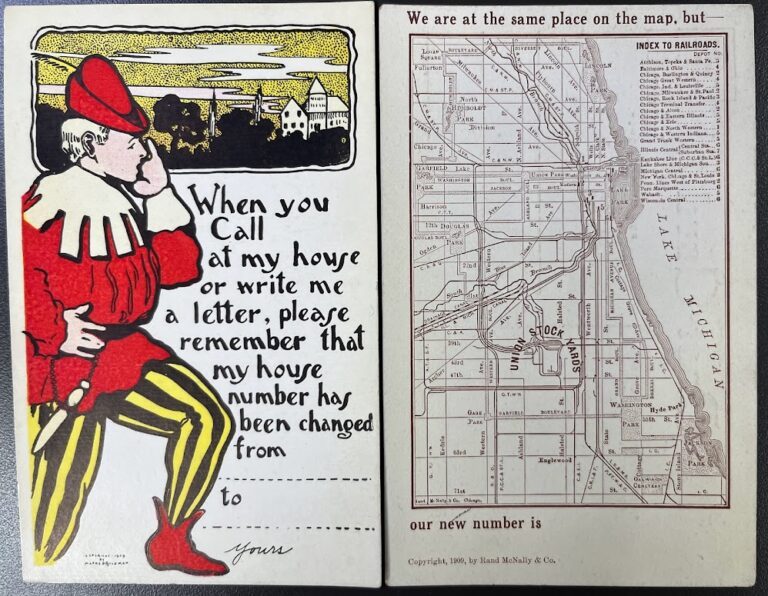

Please note that streets were renumbered in 1909 and street names changed continuously, so if you’re looking at a volume published prior to 1909, you’ll want to use our address conversion guide to determine the old address of your home.

Two examples of commercially produced postcards for Chicago residents to explain their new addresses to friends, family, and business associates following the standardization of street numbering, c. 1909. Gift of Donald Friedman (2003.0246.1-31). Photograph by Ellen Keith

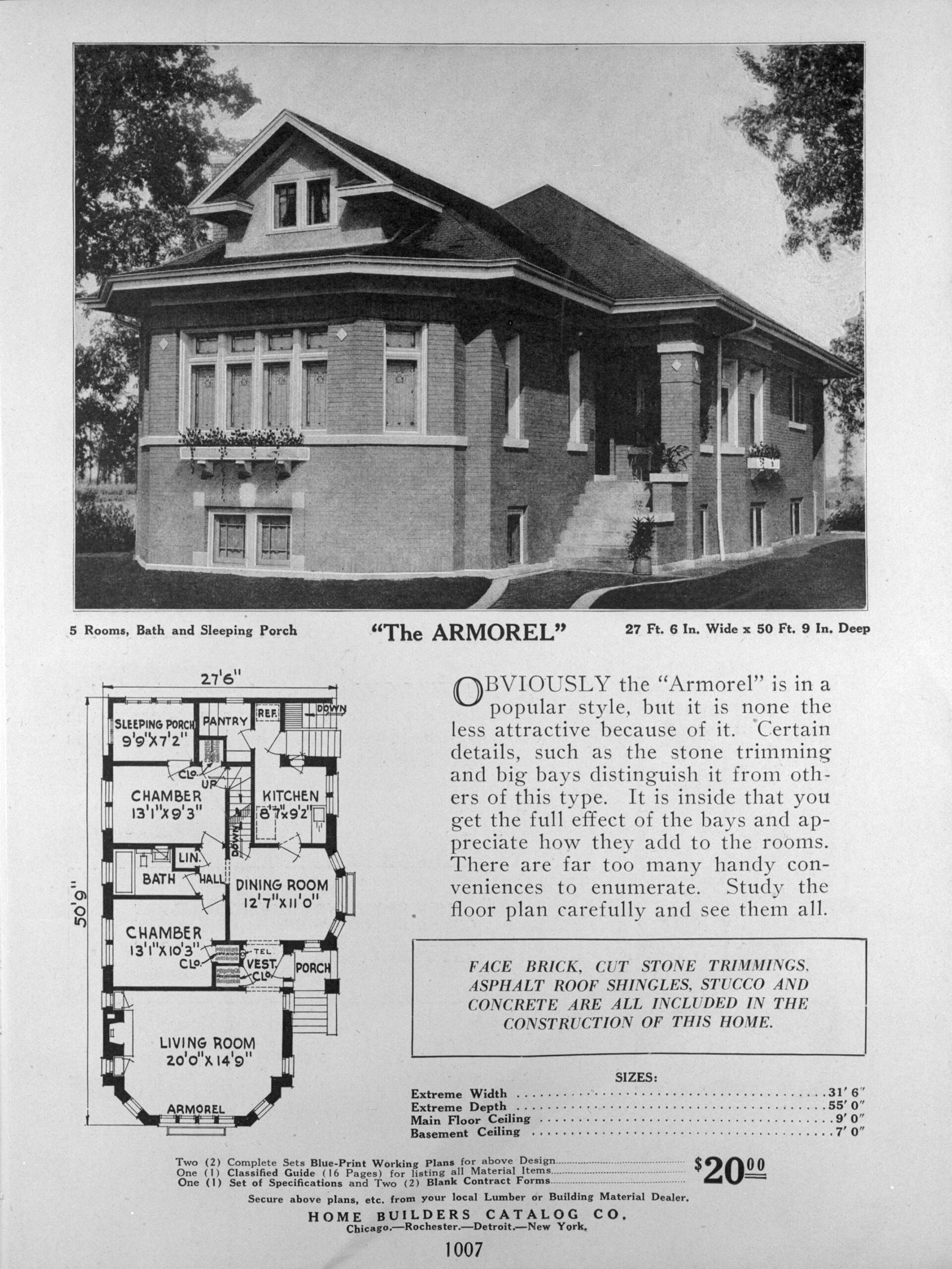

Do you think you have a home built from a kit? You may want to look at our catalogs of “prefabricated homes.” We also have a book of floor plans of selected apartment buildings.

A picture, floor plan, and text describing a bungalow called “The Armorel,” Home Builders Catalog, 1926. TH455 .H6 OVERSIZE. CHM, ICHi-015886

There’s more we can do from searching newspaper databases for articles that reference your address to checking crisscross directories and blue books for former residents. We love assisting researchers with house history, so come see us to get started!

Additional Resources

- The Chicago Bungalow Association equips homeowners with energy efficiency programs and educational resources to maintain, preserve, and adapt their Chicago bungalows and vintage homes, thereby strengthening the neighborhoods they anchor.

- The Chicago Workers Cottage Initiative celebrates this housing style, seeking to preserve the unique features of these houses, protect them from demolition, and continue their use and reuse for the next century.

- Logan Square Preservation is a community organization dedicated to educating citizens about architecture, history, and beautification.

In this blog post, CHM registrar Jamie Lewis writes about the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) and how the Chicago History Museum is working to improve the stewardship of its Native American holdings.

The gallery in Chicago: Crossroads of Chicago that discusses the region’s Indigenous tribes and European colonization. All photographs by Jamie Lewis.

Over the past year, the Chicago History Museum (CHM) has been making a few changes in how we display and handle Native American cultural items. Along with other museums in the United States, including the Field Museum and American Museum of Natural History, we are ensuring continued Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) compliance following recent legislative changes and making a concerted effort to enhance practices regarding the care and interpretation of collections and acknowledging Native tribes as experts of their own histories.

What has CHM removed from display and why?

CHM has removed several items from display in the exhibition Chicago: Crossroads of America on the Museum’s second floor as well as from the small alcove in Imagining Chicago: The Dioramas on the first floor. These cultural items are either known or likely to have been taken from Native American burials. We consider these types of items to be “culturally sensitive,” meaning that there is a cultural reason for us not to display them, and there may be special, culturally specific guidelines for caring for them. While some non-Native people may feel that displaying funerary items is acceptable, CHM believes most Native American communities do not want these types of items on public view. And in fact, some believe that museums should not really have them at all. NAGPRA, passed in 1990, is one legislative measure that was created to ensure the protection of Native burials and to facilitate the return of human remains (or ancestors) and funerary objects, as well as other important cultural items.

The Native American section of Imagining Chicago: The Dioramas.

What is the purpose of NAGPRA?

The looting of Native American burials and sacred sites has been part of the United States’ history from earliest European contact and continues to this day (1). Laws exist all over the country criminalizing the vandalization of cemeteries and graves but have historically failed to protect those of Native people (2). The passage of NAGPRA is only one chapter in a long history of a struggle for equal protection under the law. For over thirty years, museums and federal agencies have been confronted with reevaluating business as usual, resulting in a lot of positive changes for the rights of Native people, and in some cases improving relationships between museums and tribes.

Why are these changes happening now?

Among other significant changes, new NAGPRA regulations prohibit the display of Native American funerary items without permission from the appropriate tribe(s). The State of Illinois also passed the Human Remains Protection Act in 2023, which in part reinforces the same restrictions—it is now illegal for museums to display any human remains or funerary items. CHM is actively working with tribal representatives to ensure compliance with these laws.

In addition to following the legal requirements, CHM also aims to improve its practices regarding the care and interpretation of its collections. By acknowledging Native tribes as experts of their own histories, we may begin to repair some of the damage caused by museums in the past. This shift is part of a larger movement in the museum field to return some agency to source communities in the stewardship of their cultural heritage.

If someone has comments or feedback about the Native American section in Chicago: Crossroads of America, how can they share them with the Museum?

CHM is committed to improving our practices and acknowledges that the 2006 exhibition largely omits the perspective of the Native inhabitants who were here for thousands of years before Europeans arrived. CHM is beginning the process of rethinking Chicago: Crossroads of America. If you have any questions or would like to share your thoughts, please email us at repatriation@chicagohistory.org.

Sources Cited

1 .“Desecration of Indigenous Burials and Other Sacred Sites.” National Park Service. Accessed April 3, 2024.

2. Jack F. Trope and Walter Echo-Hawk, “The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act: Background and Legislative History.” Arizona State Law Journal 24, no. 35 (1992): 35–77.

Additional Resources

Michael F. Brown, Who Owns Native Culture? (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003)

Chip Colwell, Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America’s Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017)

Roger C. Echo-Hawk and Walter Echo-Hawk, Battlefields and Burial Grounds: The Indian Struggle to Protect Ancestral Graves in the United States (Minneapolis: Lerner Publishing Group, 1994)

Amy Lonetree, Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National and Tribal Museums (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012)

Today, April 4, marks World Rat Day. In this blog post, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman writes about the rat-shaped hole in Chicago’s Roscoe Village neighborhood, rats in religion, and how the secular comes hand in hand with the sacred.

Pest Control, Rat Gnawing Cable, May 5, 1922. CHM, ICHi-164646

Having earned the title “rattiest city” in the United States for the ninth year in a row, rats hold a special place in Chicagoans’ hearts and urban lore. While some debate if Chicago indeed has the most rats per capita in the country (we’re looking at you New York), it seems to be widely accepted that Chicago reigns supreme in rat obsession if not in actual numbers.

Chicago Rat Hole, 2024. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Chicago’s love affair with the rat has recently found a resurgence with the rediscovery of a concretized imprint of a furry rodent in a sidewalk in Roscoe Village. Now known, belovedly or bemoaningly, as the Chicago Rat Hole, it probably needs no further introduction, but I’ll briefly recap its known history just in case.

Original photograph of the Chicago Rat Hole from Winslow Dumaine’s tweet, 2024. Wikimedia Commons

Residents of Roscoe Village claim the imprint of Chicago’s furry frenemy has been in the sidewalk for decades, mysteriously appearing after fresh sidewalks were poured. It was not until January 2024 that it would reach viral status based on a quick-witted tweet, resulting in an onslaught of visitors. This quickly snowballed into visitors (some would call pilgrims) leaving objects (some would call offerings) by the hole, resulting in a happenstance shrine. There have been pilgrimages, proposals, and even a wedding all held in the presence of Chicago’s latest tourist trend, sometimes to the great chagrin of its neighbors. Despite multiple attempts to fill it back in, it miraculously remains.

As curator of religion and community history, my role looks at the ways in which Chicago has been shaped by its innumerable religious communities, expressions, and places. Sacredness and belief are found and conceptualized in diverse and unexpected ways, and religion has often spontaneously appropriated spaces around the city, including through things not traditionally considered “religion.” This line of thinking brought my colleagues and me to ask ourselves the question: Is the Chicago Rat Hole just silly, completely sacrilegious, or something uniquely sacred to Chicago?

Inflatable rat in Bloomington, Illinois. Photo by Aklibbee, Wikimedia Commons

To begin, let’s take a quick stroll through rats’ known associations. Rats as creatures are reputationally mixed. On the one hand, they are intimately associated with illness, disease, and destruction, making them a verifiable pest. Their image can be negatively conflated with conniving behavior, as in the Pied Piper of Hamlin, or with picket line crossing, as with Chicago’s own “Scabby the Rat,” an inflatable rat used to bring attention to labor issues.

On the other hand, rats are positively recognized for their tenacity, quick wit, and impeccable senses of taste and smell. According to the City of Chicago, these incredible creatures are exceptional at climbing and swimming, can chew through hard materials like wood and plaster, can tread water for up to three days, and can survive a five-story fall unharmed.

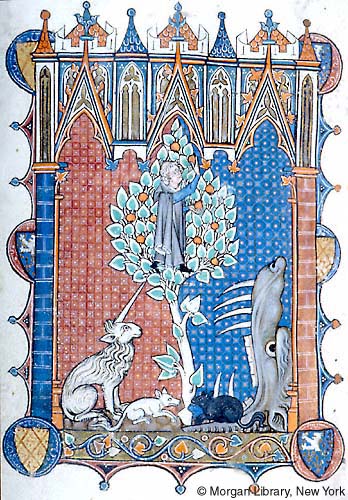

Page from the Psalter–Hours of Yolande de Soissons (1280–99) showing two rats gnawing on the trunk of the Tree of Life. MS M.729, Morgan Library and Museum Collection

This dual-sided nature also translates into religious depictions and theological understandings of rats. In Christian traditions, rats may be depicted as symbolically tied to evil and sin, sometimes depicted near Judas, the betrayer of Jesus in the Books of the Gospel, or shown in moments of destruction, as in the psalter image above.

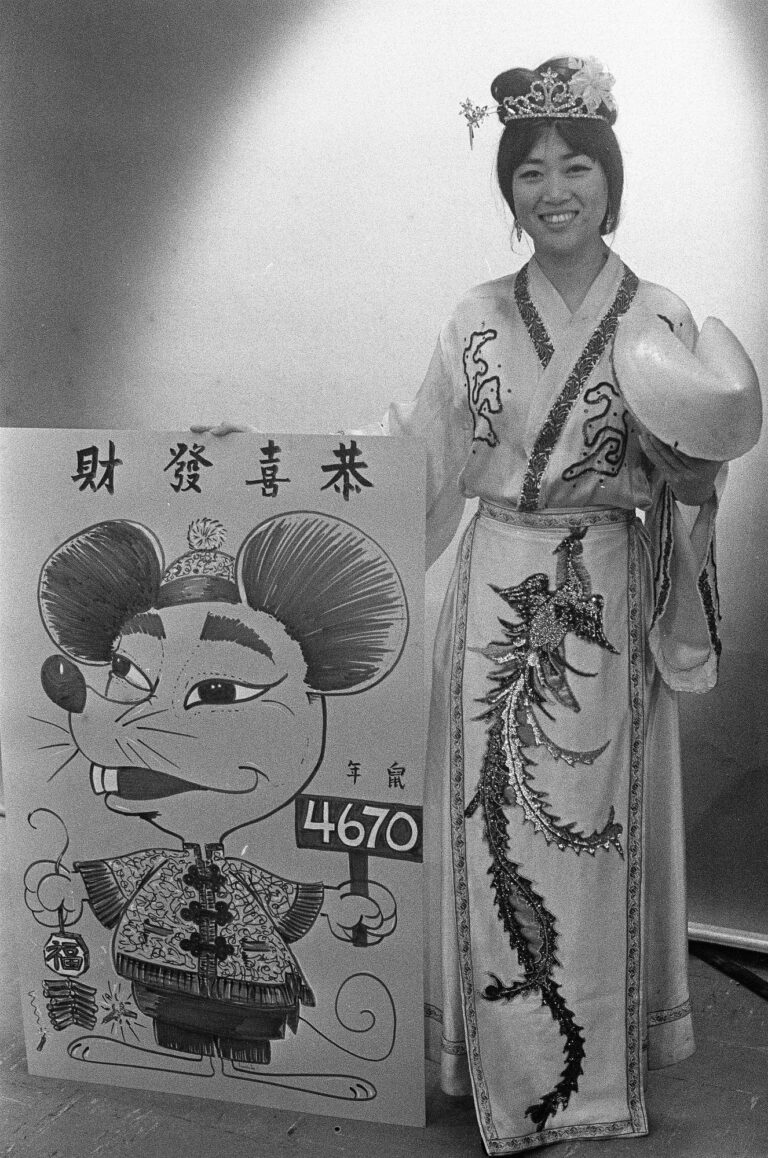

A woman in a traditional Chinese garment stands with a year of the rat sign celebrating the Chinese New Year, Chicago, January 17, 1972. ST-19033122-0006, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

In other traditions, rats are centered for their positive attributes. For example, the Chinese zodiac places the rat at the start of the twelve-year cycle, associating it with traits of intelligence, perseverance, and optimism.

Above: Karni Mata Temple and below: rats drinking at the Karni Mata Temple, 2016. Photographs by Günther Jontes, Wikimedia Commons

In Deshnoke, Rajasthan, India, the Karni Mata Temple or Madh Deshnoke celebrates the Hindu goddess Karni Mata who chose kābā (rats) as a symbol of power. The temple cares for thousands of rats, including providing prasad (food offerings), as the kābā are considered holy.

This handful of examples show us that the place of the rat in religion may be conflicting, but there are established iconographies, associations, and spiritual roles. The rat is justifiably religious in real and respectful contexts. But, does this necessarily translate to the comedic irony, touristy kitsch, or public nuisance that is the Chicago Rat Hole?

Our Lady of the Underpass (aka Salt Stain Mary), 2007. Photograph by Daniel X. O’Neil. Wikimedia Commons

The rat hole would not be the first time a happenstance shrine has resulted in a debate about material religion in Chicago. Our Lady of the Underpass, which first appeared in 2005 along Fullerton Avenue beneath the Kennedy Expressway, to some was merely a salt stain and to others became an undeniable revelation of la Virgen de Guadalupe. Catholic tradition, in fact, includes a long heritage of recognizing Marian apparitions, meaning sightings of the Virgin Mary in everyday settings and among ordinary objects. Apparitions may go through a process by which church leadership approves a given encounter as a true revelation. However, countless examples persist of someone seeing or interacting with an image of Mary, Jesus, or other religious figures that falls outside traditional parameters but remains important to believers on a spiritual level or as a secular cultural icon. In many cases, it’s a blurring of the two.

Logo for Rat Mass. Courtesy of Rat Mass.

To further explore this mixing of the spiritual with the everyday, I reached out to local rat religion experts Perry Letourneau and Joseph Bryant, makers of “ratology” and hosts of Rat Mass. Rat Mass was born in January 2023 from Joseph and Perry’s searches for meaningful community and shared interests in comedy. Through monthly performances at the Annoyance Theater in Lakeview, Rat Mass incorporates recognizably religious elements— hymns, sermons, communion, baptism—but all redefined through the lens of a Chicago rat.

Church of Ratology at the Chicago Rat Hole, 2024. Courtesy of Rat Mass.

In January 2024, at the peak of rat hole popularity, they claimed holy stewardship as the Church of Ratology. However, the rat hole was not inherently on the radar for Letourneau and Bryant when they began. The choice of the rat came from a desire to distance themselves from religious practices they had found harmful, and they searched for an animalistic representation of qualities they both admired. For them, rats are noble and adaptable with an innate ability to survive and thrive in the harshest of conditions. Additionally, because there are so many rats in the city, their presence creates a shared point of connection for Chicagoans. It’s an everyday experience that becomes a part of Chicago living, and Rat Mass’s sold-out shows suggest that experience has a real draw.

A comedy performance that parodies religion may not seem inherently like the answer for separating the sacrilegious from the sacred. However, in America’s shifting religious climate, it does reveal something very real. Religious expression is changing, but the need to find meaning and create community remains. Letourneau and Bryant asserted that while Rat Mass is a comedy performance, it is a real community gathering centered on traits they genuinely admire and to which they aspire. They see traditional religious services also as a mixture of the performative with the metaphysical as the meaning is formed by those who participate, and ratology is simply their expression.

Chicago Rat Hole, 2024. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

So, what does this mean for Chicago’s beloved rat hole? Scholars David Morgan and Sally M. Promey affirm the role an image plays in both forming memory and creating ritual in public religious expression. Images become an important way of marking group identity and creating a sense of belonging. In this case, the meaning centers on the image of the humble Chicago rat. For numerous Chicagoans, it has led to ways of coming together: performances, community gatherings, life events, general jokes, and serious conversations. It reminds us that the secular comes hand in hand with the sacred. Tourists can also be pilgrims. Kitsch may also be reverence. The Chicago Rat Hole can be simultaneously silly, sacrilege, and genuinely sacred.

To mark 100 years since Beulah Annan was accused of murder in a case that fascinated the city, CHM historian Jojo Galvan takes a closer look at the incident and how it inspired a well-known Broadway musical.

Indulging in true crime tales for leisure, whether binge-watching the newest documentary or the in-ear vibration of familiar voices and sound effects animating our favorite podcast, isn’t a new phenomenon. Time and again, rendition after rendition, some of the darkest stories in our collective history continue to draw in a breadth of diverse audiences. But why?

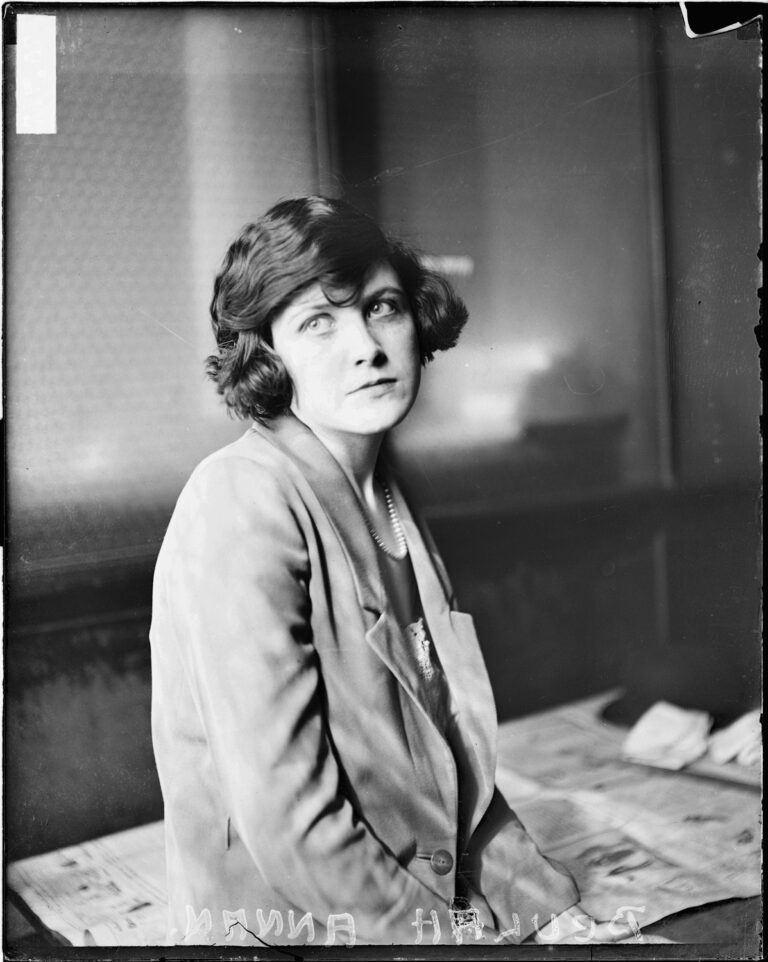

Beulah Annan, accused of killing her lover, Chicago, c. April 1924. DN-0076798, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

One of these endlessly told stories happened 100 years ago on the South Side of Chicago, in an unassuming apartment complex in the North Kenwood neighborhood, introducing the world to the historical character of Beulah Annan. Born in 1899 in Kentucky, Beulah and her husband, Albert, arrived in Chicago at the start of the 1920s. They both held blue-collar jobs to make a living, with Beulah finding work as a bookkeeper for a local laundry. Shortly after arriving in the city, she began having an affair with a coworker named Harry Kalstedt. On April 3, 1924, Beulah and her lover had a secret rendezvous in her apartment while her husband was at work. According to Beulah’s later testimony, both she and Kalstedt had been drinking wine when a lovers’ quarrel turned deadly, and she shot him in the back with a gun she kept in her home.

Another portrait of Beulah Annan, c. April 1924, Chicago. DN-0076797, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

According to various reports, the fatal shot was fired around 2:00 p.m., but authorities weren’t contacted until 5:00 p.m. when Albert got home. By the next day, a media frenzy, the 1920s equivalent of going viral, ensued. The initial fascination came not from the potential murder case, but with Beulah herself. Several outlets, including the Chicago Daily News and the Chicago Tribune, all ran headlines that focused on Beulah’s attractiveness first and the fact that she potentially committed a murder second. With a trendy bob haircut and piercing eyes, Beulah only added to the fanfare behind the case when she revealed that instead of calling the authorities, she danced to her Hula Lou record for hours as Kalstedt agonized and eventually died.

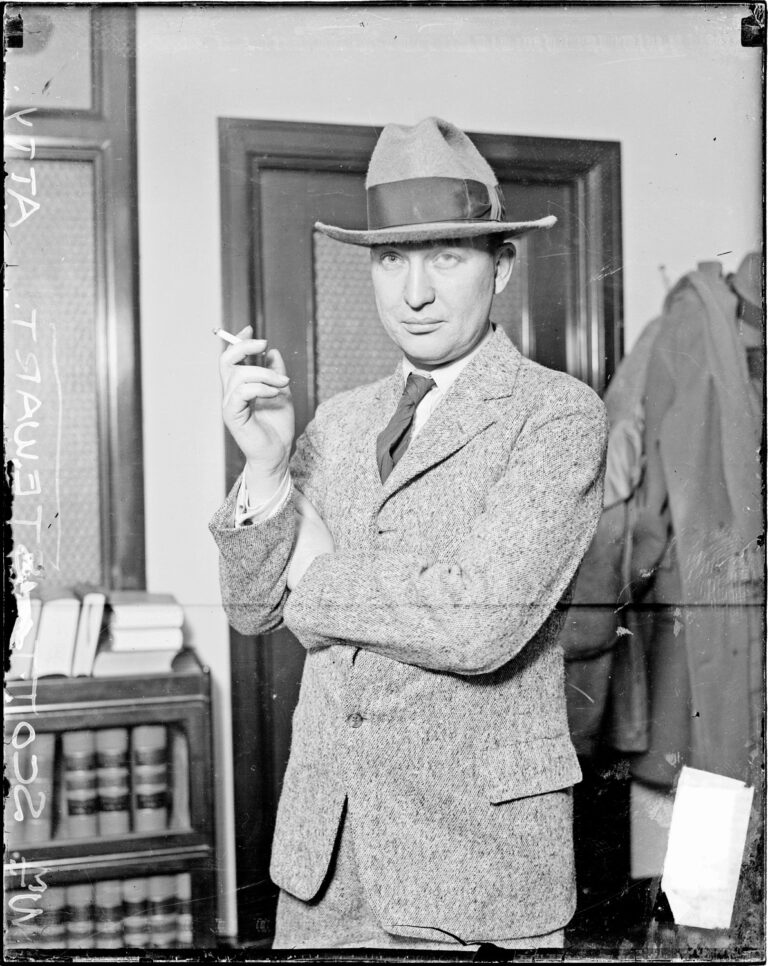

Attorney William Scott Stewart, Chicago, 1926. DN-0081521, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

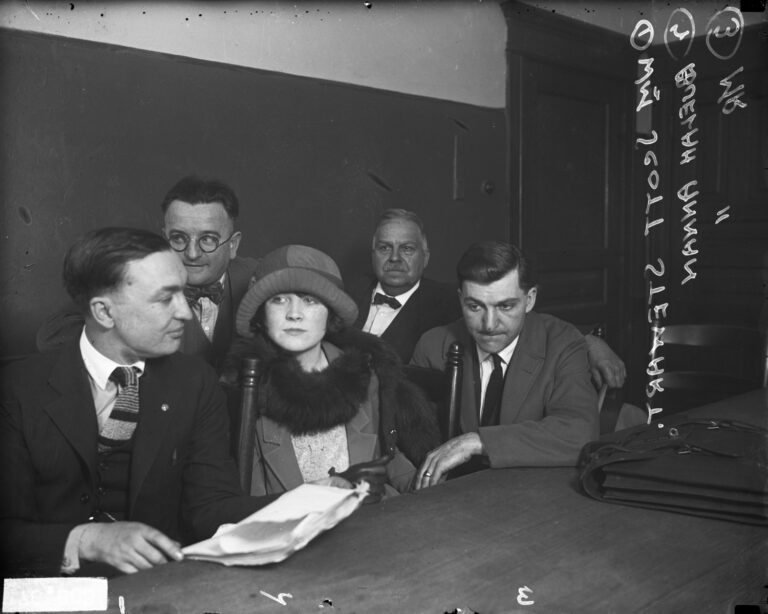

The trial was just as much a spectacle as the initial reports. Albert gathered enough money to hire well-known Chicago attorney William Scott Steward, who had achieved a level of local notoriety as the legal representative for the mob. Throughout the entirety of the investigation and trial, from the statement given to the police to her cross-examination on the stand, Beulah changed her narrative no less than three times, initially admitting to the crime and later walking back her admission, claiming she feared for her safety during the argument with Kalstedt. Beulah’s husband and relatives of Kalstedt also took the stand. On May 25, 1925, a jury acquitted Beulah of her charges, and 24 hours later she announced to the media that she had separated from Albert. Their divorce was finalized in 1926. She would go on to marry two more times before succumbing to tuberculosis in 1928.

Beulah Annan and her husband, Al (right), sitting with her attorney, William Scott Stewart (left) and two unidentified men, Chicago, c. April 1924. DN-0076803, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

While Beulah’s tale might be new to some, many are familiar with the story she inspired of scandalous love affairs and murder set in Jazz-age America. Chicago, penned initially as a play in 1926 by Maurine Dallas Watkins, the Chicago Tribune reporter on the beat for Beulah’s case, features a character named Roxie Hart, directly inspired by Beulah’s story. Chicago has been revived countless times in the theater world, including as a Broadway musical in 1975 and once more for Broadway in 1996. The 1996 revival made it one of the winningest productions in history, claiming six Tony Awards, including the award for Best Musical. In 2002, we saw Beulah’s tale again, as well as the continued success of Chicago, this time as a film directed by Rob Marshall, which won six Academy Awards, including the coveted Best Picture Award.

Front cover of the play Chicago by Maurine Dallas Watkins.

So, why do true crime stories continue to captivate us? The answer may be simple–they’re often fascinating in a way few other things are. Truth, as they say, is often stranger than fiction, and stories like Beulah Annan’s and countless others allow us to peek into how someone can cross the lines into committing one of the biggest taboos in the human experience, all from the safety of our homes or on the commute to work.

Additional Resources

- For more on using CHM’s collections to research other famous crimes, see our blog post “The Dark Side of the Windy City”

- Roxie Hart’s counterpart in Chicago, Velma Kelly, was also inspired by a real-life Chicago woman, Belva Gaertner. View digitized images of Gaertner at CHM Images.

- Read “Jailhouse Makeovers,” an excerpt from Douglas Perry’s The Girls of Murder City: Fame, Lust, and the Beautiful Killers Who Inspired Chicago

With the city’s unpredictable Midwestern weather, Chicago’s outdoor athletes have had to get creative when it comes to staying active indoors. In this blog post, editor and content manager Heidi Samuelson writes about the rise and fall of indoor baseball and its continued legacy.

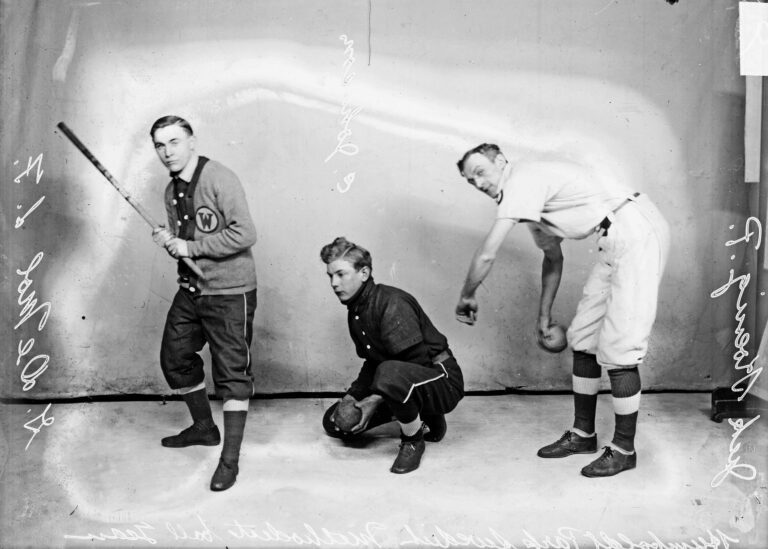

Portrait of G. De Mol (holding a bat), E. Johnson (kneeling), and Jack Hoenig (pitching stance) of the Humboldt Park Swedish Methodist indoor baseball team, 1909. SDN-007248, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Indoor baseball originated on Thanksgiving Day 1887 by George Hancock, a reporter at the Chicago Board of Trade, at the Farragut Boat Club on Chicago’s South Side. The story goes that he went to the club to find out the score of the Yale-Harvard football game, where a group of Yale and Harvard alums were following the game via telegram. Yale lost the game. After a Yale alumnus jokingly threw a boxing glove at another member who batted it away with a stick, Hancock got the idea to draw a diamond on the gymnasium floor. With a rough set of rules, the members began playing the first game of “indoor baseball” with a tightly wrapped glove and a stick. By winter’s end, the boat club was playing games with other clubs.

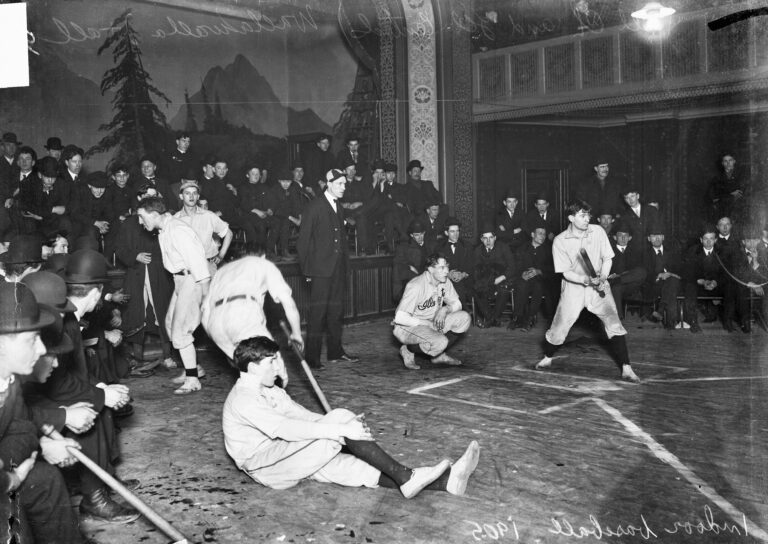

Chicago-Illinois Central indoor baseball game in a gymnasium, Chicago, 1905. SDN-003190, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The basic equipment for “indoor baseball” was a soft 17-inch ball and a thin, stick-like bat. Players didn’t wear gloves, the bases were placed 27 feet apart (compared to 90 feet apart on an outdoor baseball diamond), and the pitcher was only 22 feet from home plate. The game appealed to rowers, who were stuck indoors in winter months, but it soon spread across the Chicago area. By winter 1891–92, there were more than 100 teams organized in amateur leagues.

Group portrait of members of the Rogers Park girls’ indoor baseball team, 1909. SDN-007848, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Colleges and high schools, girls and boys, began to embrace the sport a few years later in December 1895, when 10 schools formed a league. Indoor baseball was particularly popular on the city’s West Side, and English High (later Crane Tech), Medill, and West Division (later McKinley) were dominant in league play. In 1899, West Division formed a girls’ league, having started playing intermural games in 1895, which included the West Side’s Marshall and Medill.

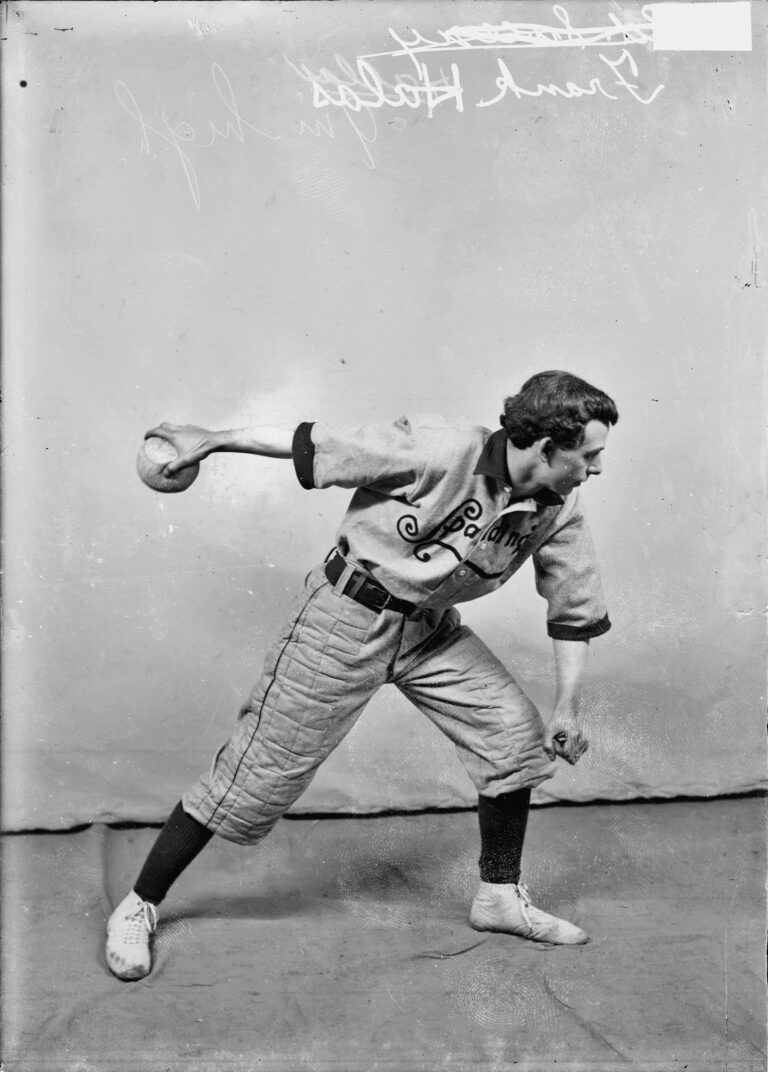

Frank Halas, indoor baseball player, winding up for a pitch, 1907. SDN-005286, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The sport was particularly popular among Czech Americans. Among its notable players were the Halas brothers, including George Halas, future owner of the Chicago Bears. George’s older brothers Frank and Walter were both standout players. The Halas brothers played at Crane Tech, and Frank also played in the Chicago Indoor Baseball League.

Around 1907, players began moving the game outdoors, changing the name to “playground ball” and later “softball.” In the 1910s, the indoor version declined in popularity, due to the rapidly growing popularity of basketball, and by the 1920s, indoor baseball was essentially nonexistent.

However, its legacy continued through 16-inch slow-pitch softball, sometimes called Chicago ball. The first 16-inch softball national championship was held during the 1933–34 A Century of Progress world’s fair. From there, a professional league formed, which existed through the 1950s. The sport is still played in Chicago today in recreational leagues, and you can visit the 16 Inch Softball Hall of Fame in Forest Park, Illinois.