Latest Posts

Project archivist Adam Melville worked with CHM archivist Julie Wroblewski as part of his graduate school practicum. In this blog post, he describes how he processed one of our largest acquisitions in recent history.

This summer, I received the exciting but daunting opportunity to process the papers of US congressman Sidney R. Yates—a 262-linear-foot collection (the equivalent of more than 500 boxes) in ten weeks. Challenge accepted!

The first step was to determine my approach. Typically, an archivist begins by surveying a collection as a whole in order to develop a processing plan and formulate series in which the materials will be arranged intellectually. The sheer size of the Sidney Yates papers, however, coupled with the fact that most of it was in off-site storage, meant we would need to alter this workflow.

After some deliberation, Julie and I decided that I would start processing items and let the series arrangement unfold as I made my way through the collection. Now, this can be a risky approach since success rests on the unprocessed items being organized in the first place (which is not always the case). But seeing as these items had come from a congressional office, we hedged our bets and it paid off: over the decades, Yates had maintained a consistent filing method, and the vast majority of materials were highly organized.

For three months, I processed the Sidney Yates papers in batches, each comprised of approximately sixty boxes. I never knew what the next batch would bring, and the arrival of new boxes from storage was met with anticipation. About one hundred boxes into the project, I had a pretty firm idea of what the series arrangement would be, although Julie and I made revisions as we uncovered new items.

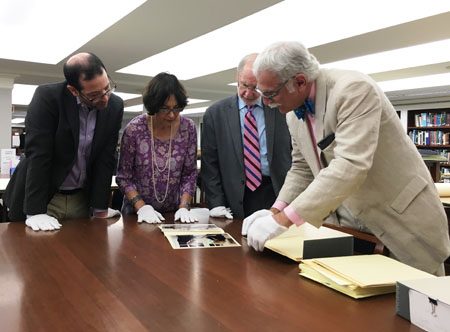

From left: Yates’s grandson, daughter-in-law, George Van Dusen (mayor of Skokie and one of the biographers), and Michael Dorf (co-biographer) examine the collection in our Research Center.

A somewhat unusual aspect of this project was that researchers were using the collection as it was being processed. This added some pressure to deliver quickly, but it also came with advantages, such as the ability to tap on-site subject experts for content knowledge. In addition, whereas a collection of this size would not normally include detailed descriptions of the contents of each box, since researchers needed immediate access to the materials, we developed a box inventory. Through some experimentation, we found a way to automate converting the working inventory into a more detailed finding aid, a technique which will help us process large collections in the future.

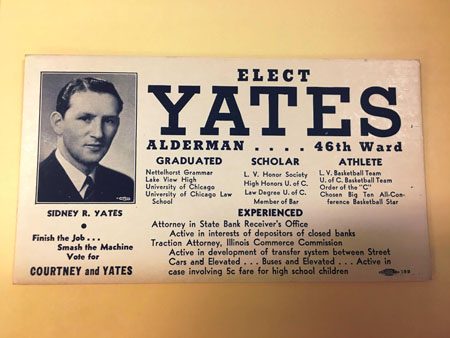

A promotional card urging Chicagoans to vote for Yates, c. 1940.

So who was Sidney Yates? A representative for the Illinois Ninth Congressional District for nearly fifty years, Yates is probably best known for his support of the arts and humanities. Other signature issues included advocating for the elderly, US support of Israel, and responsible environmental stewardship.

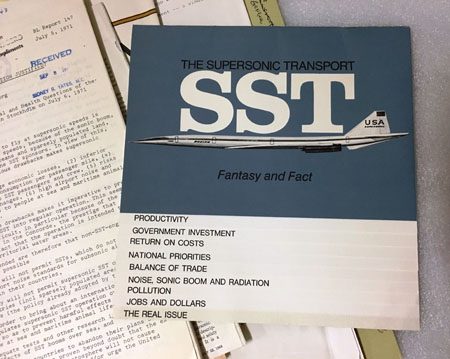

An informational booklet on supersonic transport.

A great feature of the Sidney R. Yates Papers is the breadth of subjects covered in the collection. Because of his lengthy career, the congressman was instrumental in a large range of subjects, including water diversion; Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore and radiation in US territories; Admiral Hyman Rickover and the development of the nuclear navy; supersonic transportation; the House Un-American Activities Committee; the National Endowment for the Arts; and Jewish topics including Chicago-area Jewish congregations and organizations, Soviet Jewry, Days of Remembrance, and the creation of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Additional Resources

CHM curator Petra Slinkard takes you through the process of a gallery rotation, which helps us preserve artifacts and refresh exhibitions.

The Chicago History Museum’s permanent exhibition Chicago: Crossroads of America is a 15,000-square-foot installation dedicated to our city’s rich and complex past. The installation opened in September 2006 and contains hundreds of artifacts and photographs that represent the range of Chicago’s history, from the early days of fur trappers to the Cubs’ 2016 World Series victory. Recently, we updated the sections on the city’s two world’s fairs: the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and the 1933–34 A Century of Progress International Exposition.

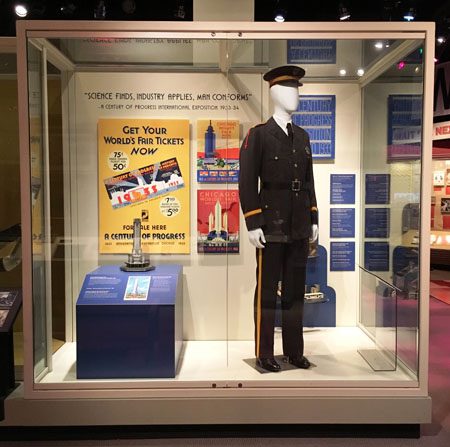

The A Century of Progress case before (above) and after (below) the rotation. Photographs by CHM staff

For the A Century of Progress section, we rotated a new slate of artifacts into the main case. We did this primarily so the objects previously on view could be inspected by our conservators, cleaned, and returned to storage to rest. Clothing is one of the most vulnerable materials to display—second only to paper—so we restrict the length of time garments are on view in order to protect and preserve them. Our secondary motivation was to rethink the overall design of the case. Daniel Oliver, the Museum’s senior exhibition designer, created a beautiful Art Deco–style case to display a variety of souvenirs from the fair. Souvenirs were popular with visitors, as they memorialized visits to Chicago and the fair and allowed their owners to share their experiences with family and friends.

Fair souvenirs on a custom-built shelving unit. Photograph by CHM staff

The costume rotated into the space is a traffic director’s uniform. Staged during the Great Depression, the fair offered much needed employment opportunities, and both men and women worked in a variety of roles. Men primarily served as traffic directors, guards, and launch captains for the lagoon. Each uniform, regardless of position, was designed to fit with the streamlined, modern look of the exposition. Even Chicago policemen serving at the fair received new uniforms, which were based on those of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

CHM costume collection manager Jessica Pushor lifts the mannequin into the display case.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the 1933 world’s fair. Three policemen stand guard, and a traffic director is stationed to the president’s right. CHM, ICHi-037690

The redesign of the case and the rotation of objects refreshed and enlivened the space, and we hope you’ll stop by the Museum to see the new additions. Stay tuned for a post in October about the World’s Columbian Exposition rotation.

- Peruse our images of the 1933 world’s fair

- Take a look at artifacts from the 1933 world’s fair

- Visit the Museum on a group tour

Senior curator Olivia Mahoney introduces the new Chicago Cubs items on display at the Chicago History Museum and reflects on the team’s past.

On November 4, 2016, millions of Cubs fans gathered in downtown Chicago for the victory parade and rally. Photograph by CHM staff.

Like Cubs fans everywhere, I’m thrilled that they won the 2016 World Series. It was a long time coming, but now that they’re champions, let’s try to forget the decades of dashed hopes and instead focus on the joy the team brought us even during the most dismal years. Yes, joy, as in sunny afternoons at Wrigley Field with a cold beer or listening to Pat Hughes on the car radio while running routine errands. Some of my happiest memories are related to the Cubs, including watching Hall of Fame players like Ernie Banks, Stan Musial, and Willie Mays or taking an afternoon off from work in the late summer to watch a meaningless but still beautiful game at the old ballpark.

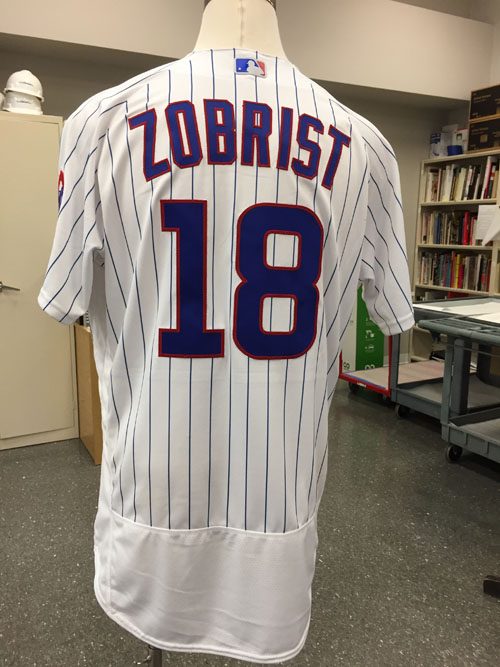

Ben Zobrist wore this jersey in Game 3 of the 2016 World Series.

CHM costume collection manager Jessica Pushor (left) and senior curator Olivia Mahoney (right) discuss the placement of the Zobrist jersey.

New memories are being made right now as we prepare a small tribute to the team that finally made our dreams come true. On September 16, 2017, the Chicago History Museum opened a new display that features materials from the 2016 World Series. The Cubs donated seats from Wrigley Field in which visitors can sit and two baseballs. Currently on display is a foul ball hit by their star third baseman Kris Bryant in Game 1—the other ball will be shown sometime in the future. On loan are a jersey and a cap worn by MVP utility man Ben Zobrist in Games 3 and 7. These items are on view in the Museum’s core exhibition Chicago: Crossroads of America located on the second floor.

CHM conservator Holly Lundberg places a baseball from Game 1 onto its mount.

While developing this new installation, I had the pleasure of touring the team’s new offices with Kris Maldre Jarosik, assistant director of the Chicago Cubs and Wrigley Field Archives. Many choice artifacts were on view there, including the 1907 and 2016 National League Championship trophies, the final out ball from Game 7 of the 2016 World Series, and a section of the green metal wall from the old bullpen area. I also had the pleasure of meeting Cubs owner Tom Ricketts. It was completely unplanned, which made it more memorable. When I told my son, a diehard Cubs fan and former baseball player, he asked if I had thanked Mr. Ricketts for what he’s done, and I was pleased to answer in the affirmative. It took a complete overhaul of the organization to break the longest championship drought in North American sports history, and Ricketts deserves a lot of credit, as do all the members of his staff, coaches, and players. Having watched umpteen baseball games at all levels, I have some sense of how hard the game is to play. It may look simple, but it’s not, and the long, grueling schedule is a test of anyone’s mettle.

Now, as the Cubs strive for another spot in the playoffs, I hope they pull it off, but if they don’t, it’s okay with me. I’m still recovering from 2016 and more than one championship a century may be too much for an old Cubs fan like me. Besides, I can always wait ’til next year!

Additional Resources

- Peruse our collection of Chicago Cubs images

- Browse the documents in our Chicago Cubs records, 1873-1966

Get to know Chicago cultural maven Lois Weisberg with the contents of her collection in our Research Center.

Small only in stature, Lois Weisberg was a big presence in Chicago’s civic and cultural life for seven decades. Everything about her seemed larger than life, including a circle of friends that ran the gamut from comedian Lenny Bruce to our own Gary T. Johnson. She could be seen bustling through the city, cigarette in hand, wearing oversized, bejeweled glasses, and driving a car that seemed too large for her unless, of course, you knew her. And seemingly everyone did, in fact, know Lois.

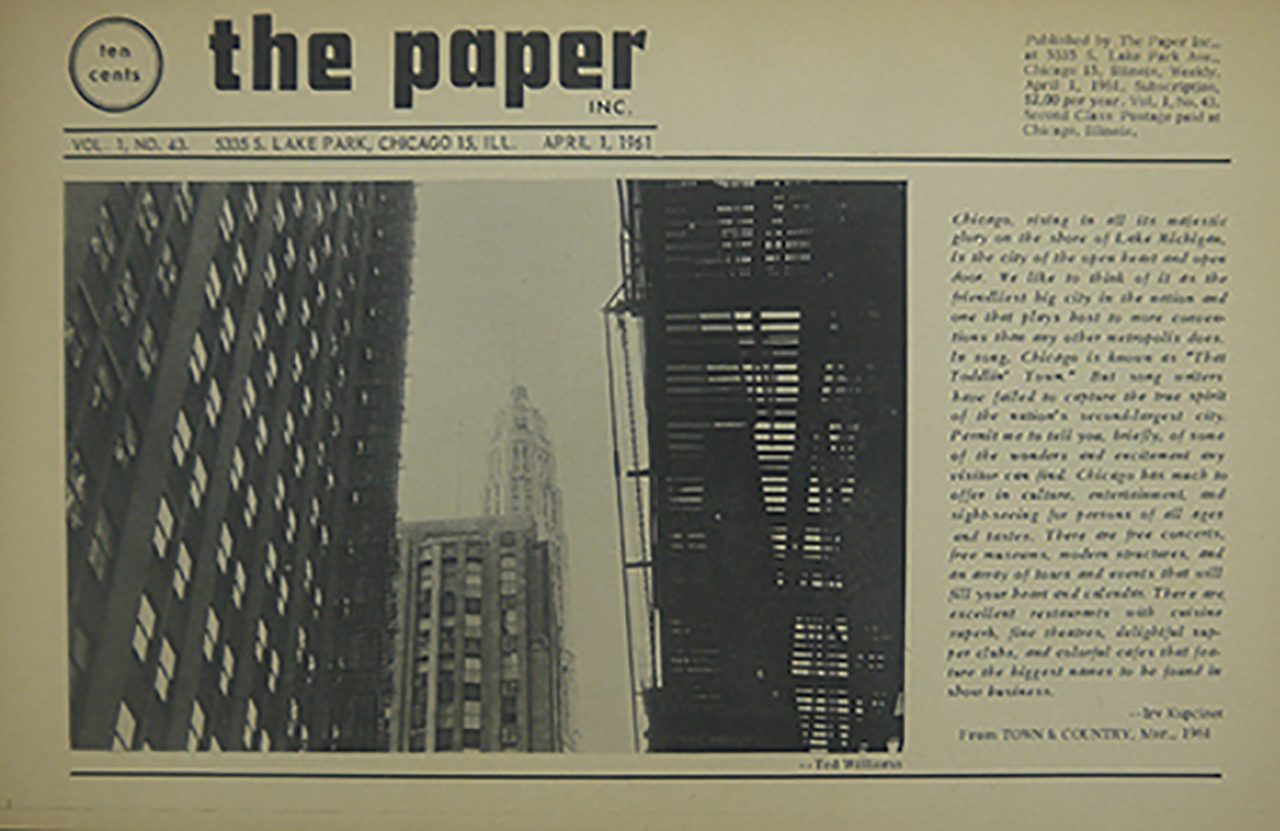

Born Lois Porges on May 6, 1925, Weisberg was raised in the Jewish section of Chicago’s Austin neighborhood. Her father was a prominent lawyer who served under Illinois’s first Jewish governor, Henry Horner, and her uncles were a part of city’s Democratic political machine as precinct captains. As a child, Weisberg was drawn to the arts and nurtured a passion for them throughout her life. After graduating from Northwestern University, she founded a theater company dedicated to the works of George Bernard Shaw, going so far as to personally solicit money from John D. MacArthur for the centennial of Shaw’s birth in 1956 and founding The Paper, an underground arts and culture-focused weekly.

Front cover of “The Paper,” April 1, 1961. Box 12, Folder 17

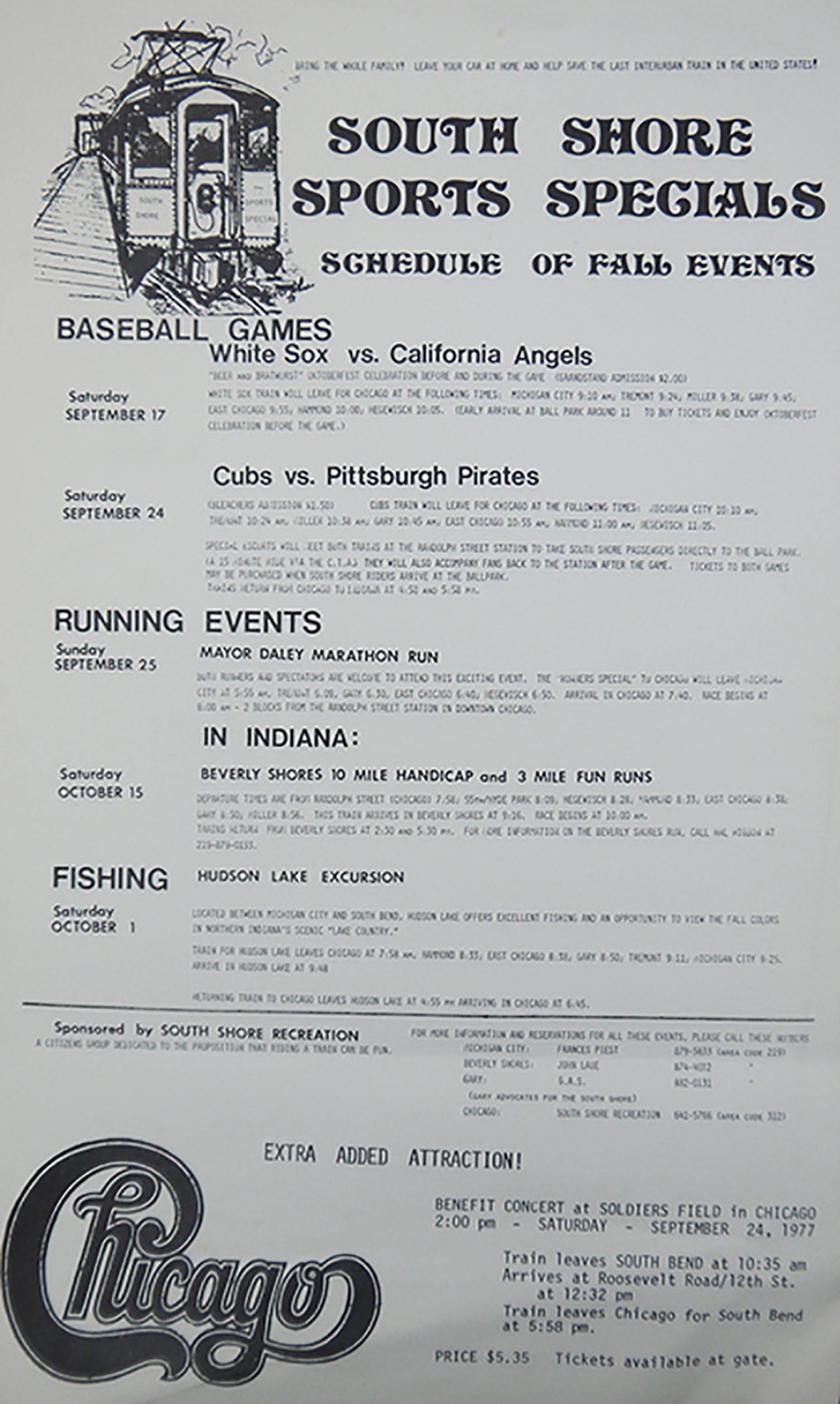

Weisberg was not the type to sit idle in the face of a problem. Concerned with the potential end of daily railroad service from Chicago to South Bend, Indiana, she founded South Shore Recreation to promote and sponsor sightseeing trips and other outings; worried about the disrepair of the city’s communal spaces, she helped establish Friends of the Parks. Materials chronicling Weisberg’s part in the earliest days of both organizations can be found in her collection.

Flyer for South Shore Recreation, whose events encouraged community members to ride the South Shore Rail Line. Box 6, Folder 1

Professionally, Weisberg worked tirelessly at Business and Professional People for the Public Interest and later as executive director of the Chicago Council of Lawyers. Politics was also an important part of her life, serving as campaign manager for one of Congressman Sidney Yates’s reelection bids and as an active supporter of Harold Washington’s successful 1983 mayoral campaign. In 1983, Washington named Weisberg director of the Office of Special Events.

Mayor Harold Washington (center) appointed Weisberg (right) director of the Office of Special Events, her first position at City Hall. Box 73, Folder 23

In 1989, Mayor Richard M. Daley appointed Weisberg commissioner of the Department of Cultural Affairs, a position she held for more than two decades—the largest portion of the collection consists of materials relating to this timespan. Weisberg was responsible for many of the cultural events that have become synonymous with Chicago itself, such as the Taste of Chicago. Her commitment to public art led to her to create Gallery 37, which commissioned student artworks to cover up graffiti, as well as the world-renowned Cows on Parade exhibition.

Weisberg speaks at a press conference for the Cows on Parade, June 15, 1999. Box 73, Folder 6

Weisberg passed away on January 13, 2016, and is remembered fondly for bringing the arts to the people of Chicago. More importantly, she brought people together. Weisberg was so famous for her extensive network that Malcolm Gladwell wrote a New Yorker article entitled, “Six Degrees of Lois Weisberg” (January 11, 1999) in which he mused: “Lois is far from being the most important or the most powerful person in Chicago, but if you connect all the dots that constitute the vast apparatus of government and influence and interest groups in the city of Chicago you’ll end up coming back to Lois again and again.”

- Explore the Lois Weisberg papers in our collection

This summer Ina Cox worked on the Chicago History Museum’s latest collaborative initiative, the North Lawndale History Project, developed by Paul Norrington, president and founder of the K-Town Historic District Association, Inc. She was the Senior North Lawndale Minow Fellow working with Peter T. Alter, the Museum’s historian and director of the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History. This is the fourth post in a series about the project.

As I look back on this summer, reflecting on the time Wynton, Zilah, Peter, and I have spent working together, one feeling stands out: the work is just getting started. Before the project got underway, we assessed the popular narrative about North Lawndale to get a sense of where we were starting. I read The American Millstone: An Examination of the Nation’s Permanent Underclass (1986), the Chicago Tribune’s notoriously problematic depiction of the community as a “permanent underclass.”

I asked Zilah and Wynton to report on the information universe surrounding North Lawndale by exploring its representation in a variety of databases—everything from the Chicago Public Library Special Collections to Twitter—so that we could assess the tone and quality of the public narrative. After only twenty-seven working days, our team successfully added six oral histories to the historical record about North Lawndale community activism and leadership.

From left: Zilah Harris, Audrey Dunford, Wynton Alexander, and Ina Cox, 2017. Photograph by Paul Norrington

If you’re not familiar with the work of oral history, you might not think that six is much at all. But, when done right, the process is painstaking. We had to find willing narrators who have significant life experiences and connections to North Lawndale. Then, we had to secure a time and place for each interview. Once we established that, we conducted substantial historical research and familiarized ourselves with the narrator’s background. We drafted questions, interviewed the individual, and archived it.

We were a veritable oral history factory this summer. I am very proud of what we accomplished—particularly of the growth of Zilah and Wynton into budding young oral historians! I came into this position with research and writing skills. I am leaving with a newfound appreciation for the centrality of interpersonal relationships in public history work. For that I am grateful to Peter, Wynton, and Zilah for teaching me what mentorship is all about.

And yet, there is still so much that remains to be done. I don’t think any of us believed that we could archive a comprehensive portrait of North Lawndale—or imagined that such a thing would even be possible. Once you start on a project like this, you can’t help but see the holes that exist and the needs that remain unaddressed. Almost every narrator spoke to the hope that telling North Lawndale’s story would make it a better place.

They agreed to be interviewed because they understand the power of storytelling, the narratives that become history. And in all of them we could sense the yearning for a brighter future if only by encouraging others to see the neighborhood through a different lens. Beyond the issues that plague the community, North Lawndale suffers from a reputational problem. Public history, particularly oral history, helps by telling the story over again.

Blanche Suggs-Killingsworth, 2017. Photograph by Ina Cox

Listen to Blanche Suggs-Killingsworth of Neighborhood Housing Services and the North Lawndale Historical and Cultural Society talk about what it means to serve North Lawndale and her perspective on what Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination meant for her community.

Hear Audrey Dunford of the North Lawndale Restorative Justice Community Court talk about how imprisonment often results from her community being misunderstood.

In this installation of the North Lawndale History Project series, North Lawndale Minow Fellows Zilah Harris and Wynton Alexander discuss the favorite parts of their oral history interview with a former Black Panther.

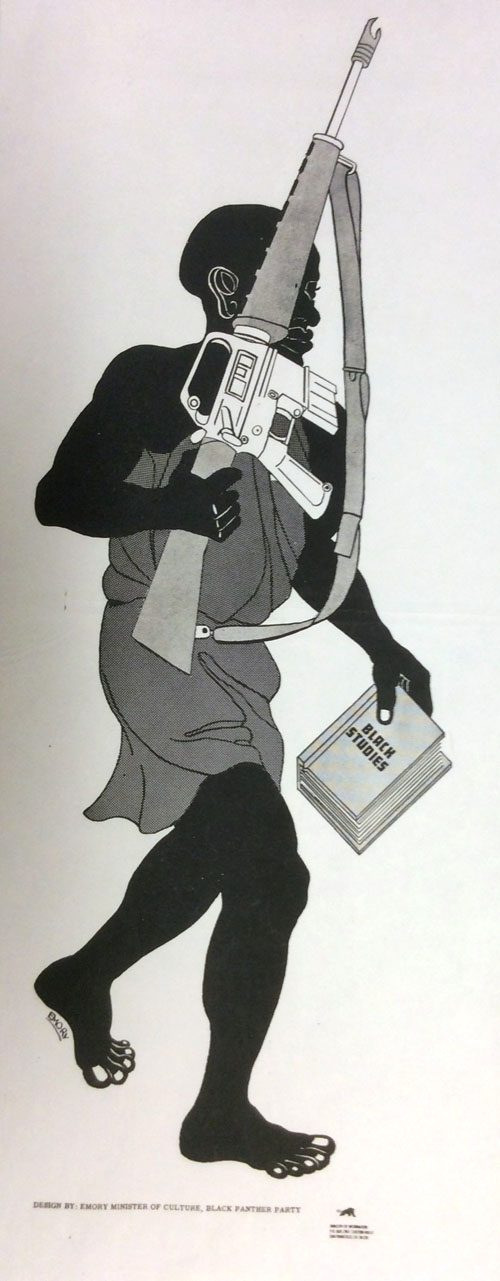

Billy Lamar Brooks Sr., also known as Billy Ché or Ché, was born in Mississippi in 1948 and moved to Chicago in 1951. Eventually, his family settled on South Kedvale Avenue in North Lawndale. During the late 1960s, he was the deputy minister of education for the Black Panther Party’s Illinois chapter. Billy Ché’s job was “to insure that all party members understood the platform.”

Billy Lamar Brooks Sr., 2017. Photograph by Peter T. Alter

Zilah writes about what she enjoyed the most.

Billy Ché Brooks is a man to remember. To even have the opportunity to interview someone of such importance and who had such an impact on the black community was a humbling experience. At the same time, Ché is an everyday guy with a life filled with hard work and dedication to his people and community. It was great to interview him because I was getting in on an important piece of history.

The most surprising part of the interview was the impressive amount of times this man was confident enough to curse. He was completely himself and obviously comfortable in his skin. Ché told us about his work as a Panther, specifically as a leader in the Illinois chapter’s education department. He spoke about working with young people at his former job at the Better Boys Foundation and how it impacts his focus on specific issues in the community. Ché also told us how the loss of his son made him stronger. In the end, Billy Ché Brooks was an amazing and inspiring interviewee.

A Black Panther poster (1969) highlighting the role of education in the Black Panther Party, which Billy Ché supported when he was a member.

Front and back of a Chicago Seed Extra poster (1969), which explains how Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, at 21 and 22, respectively, and leaders of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, were killed by law enforcement at 2337 West Monroe Street.

Wynton was struck by a specific part of the interview.

What surprised me the most during the interview with Billy Ché was when he asked me how many times I have been to jail. When he was younger, he went to jail because he was standing up against things he felt were wrong. At first I asked him, “How many times have you been to jail?” Then, he flipped the question on me, and I responded with, “Zero.” “Really,” Mr. Brooks said and then asked, “How old are you?” I responded, “Fifteen.” He continued, “Do you think you will ever go to jail?” After I said, “Never,” his response was “When I was your age, I thought the same thing.”

That really stuck out to me. It’s amazing how people judge young black males. Just because I am black and young does not mean I should be labeled a certain way. People may think the majority of young black males are not doing well because of the things they see in the media, but the media really focuses on the bad things people do, not the good. People need to learn to stop thinking “one bad apple spoils the whole bunch” because that is just not the case.

Listen to Billy Ché discuss his experience as a student at Woodrow Wilson Junior College, now Kennedy–King College.

In this clip, Billy Ché talks about the Black Panthers’ relationship to gangs.

- Explore the Smithsonian’s holdings on the Black Panther Party

- See the Black Panther Party materials at the Library of Congress

In fashion exhibitions, many things vie for attention. The focus, of course, is on the garments with their rich fabrics, vibrant colors, and sparkly embellishments. But, how do these pieces go from collection storage (hanging on a rack or packed in a box) to beautifully mounted on a mannequin?

A common misconception is that the clothing is altered to fit the mannequins, but the opposite is actually true: each mannequin is modified to fit its garment. While many options are available to achieve this, a widely accepted practice is using high-tech tools: pantyhose and polyester fiberfill or batting (the soft, squishy stuff used between blankets). Museum staff and contractors used this technique in Making Mainbocher: The First American Couturier.

First, we considered the size and silhouette of the piece as well as environmental factors, such as gravity and light. After a conservation assessment to confirm the stability and condition of a garment, we took careful measurements, selected a mannequin, and covered it with nylon pantyhose to create a second skin to which we would sew the fiberfill. It was important to consider the time period of the garment and build the foundation accordingly. These photographs show the build out for a 1947 strapless evening dress. The padding creates a higher bustline and fuller hips, bosom, and backside, achieving the much-loved S-curve.

Next, we used a layer of pantyhose to cover the loose fiberfill and added appropriate underpinnings (petticoats) for additional shape. Once the form matched the garment’s measurements and achieved the desired silhouette, we dressed and accessorized the mannequin.

But what happened when a mannequin didn’t fulfill the needs of its costume?

Our seersucker WWII Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) uniform required shorter arms to fit its sleeve length, so we had to build new arms and attach them to preexisting mannequin hands. To achieve this, we used Fosshape and Ethafoam. Fosshape is a low-melt synthetic polyester fiber similar to felt. In its non-activated state, it can be sewn and manipulated, like fabric, but when heat is applied, the fibers melt and harden. Ethafoam is dense foam that can be carved. These materials are chemically stable to reduce off-gassing (chemical breakdown) and protect the overall wellbeing of the Museum’s collection.

We began by wrapping a preexisting mannequin arm with cellophane and sewing pieces of Fosshape around it like a close-fitting sleeve. Heating the Fosshape created a shell, so when we removed the arm, an exact replica remained. We then trimmed the shell to the appropriate length and fitted it with lightweight but rigid Ethafoam for stability. Using hardware and hot glue, we secured the new arm to its hand and then covered it in pantyhose for easier dressing.

To attach the new arms to the mannequin body, we duplicated the ball-and-socket joint of a human shoulder. By wrapping the original mannequin arms in Fosshape, we created yokes (or shoulder sockets). After confirming that the arms were a good fit, we used heavy-duty Velcro to attach them to the yokes. The last two photographs show the final dressing and test-fit of the uniform.

So, the next time you hear someone muse, “What’s under there?” You can respond, “A lot more than you think!”

Additional Resources

- See all of the garments featured in Making Mainbocher: The First American Couturier

- Learn more about our Costume and Textiles collection

- View our Google Arts & Culture story Making Mainbocher: The First American Couturier

Michael Hall, an independent contract mount maker, worked on Making Mainbocher as well as previous Chicago History Museum exhibitions, including Charles James: Genius Deconstructed and I Do! Chicago Ties the Knot.

“What is strange to us today will be familiar to us tomorrow.”—Mayor Richard J. Daley

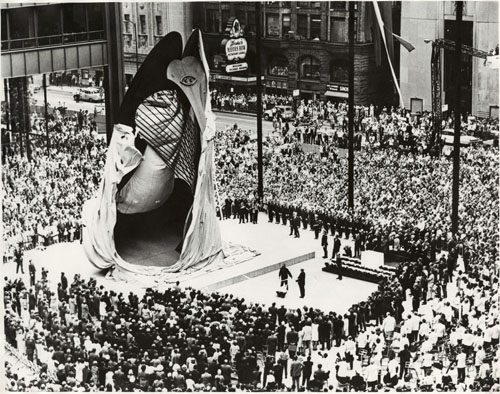

On this day in 1967 at 11:00 a.m., about 50,000 Chicagoans gathered in Civic Center Plaza, now Richard J. Daley Plaza, for the dedication of the first public art work commissioned by the city. Its story, as stated in the ceremony pamphlet, is “a dramatic illustration of the atmosphere and the spirit which drew this artist and this city together.”

The unveiling of the Picasso sculpture on August 15, 1967. Photograph by the Chicago Daily News, CHM, ICHi-092975

In 1963, the Public Building Commission of Chicago decided to build a new Civic Center and adjoining plaza in the Loop. To include a fountain in the plaza was a given, but to include a sculpture was trickier. In the Chicago Architects Oral History Project, William Hartmann, a partner at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, one of the supervising firms, opined, “Public art is difficult. Unless you do it right.” A monumental project such as this one required the appropriate artist, and the architects’ decision was unanimous: Pablo Picasso. Hartmann relayed their choice to Mayor Daley, who remarked, “Well, I don’t know Mr. Picasso, but if he’s the best person in the world, why don’t you go ahead and try?”

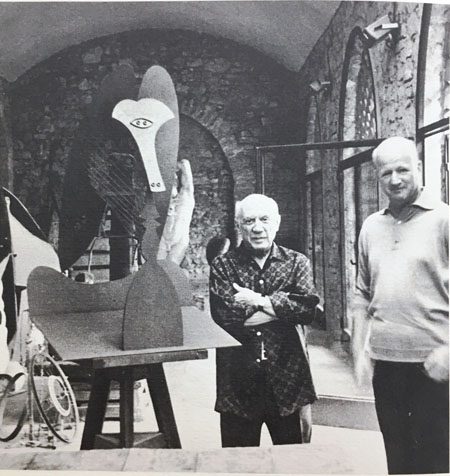

Hartmann then set out to contact a man whom he didn’t know and had never visited Chicago to ask him to create something to complement a nonexistent building. Through Allan McNab, the director of the Art Institute of Chicago, he first contacted Sir Roland Penrose, an English biographer of Picasso, who agreed to help. He suggested that Hartmann plan a visit to the south of France and let Picasso know they’d like to drop by. “You see,” Hartmann said, “You don’t just make an appointment with Picasso.”

Picasso and Hartmann with the maquette in the artist’s Mougins studio, August 1966. Image from the 1967 program pamphlet

Picasso agreed to see them, and Hartmann sought to acquaint the artist with the project: he brought photographs of Chicago, the site, and its citizens. Hartmann even included photographs of Picasso’s works owned by Chicagoans and local museums to show their recognition of and appreciation for him.

Picasso said he would think about it.

Over the next few years, Hartmann continued to visit and bring Chicago-related items, such a White Sox blazer and a Cubs hat, and updates on the project. Finally, Picasso produced a draft. Hartmann told him, “We want to commission you . . . and end up with a study I can take back.” But Picasso, who refused to discuss business, said, “You know I may not produce anything. [or] I may produce something that you don’t like . . . It’s best that we keep this low-key all the way through, keep it calm and relatively confidential.” So they did.

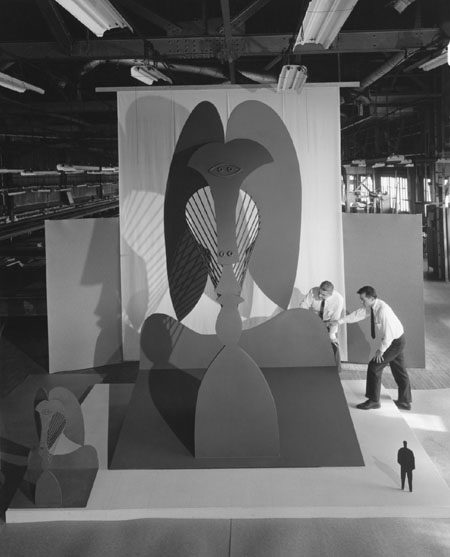

The maquette in a warehouse, 1966. CHM, Hedrich-Blessing Collection, HB-29086-F2

In 1965, the final design was presented to the Public Building Commission, who hemmed and hawed until Mayor Daley walked in and declared that he liked it. The sculpture’s Corrosive Tensile steel pieces were cast by the American Bridge Company in Gary, Indiana, where they were assembled, disassembled, and then transported to Chicago for reconstruction.

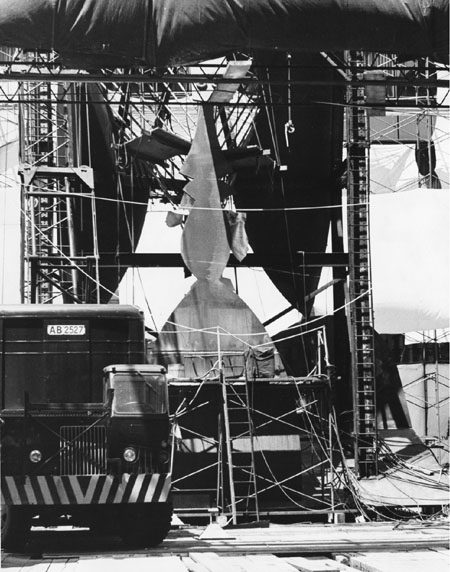

The 50-feet tall, 162-ton sculpture being assembled in Civic Center Plaza, July 1967. Photograph by Carol Sincak, CHM, ICHi-067543

Hartmann planned a grand dedication ceremony, which included poet Gwendolyn Brooks and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. When Mayor Daley removed the veil, the crowd gasped and spouted forth amusing commentary, much of which was pejorative. But to Hartmann, this reaction was better than that of indifference: “Picasso’s work, frequently, if not always has been the center of controversy. So it all fit into that pattern beautifully.”

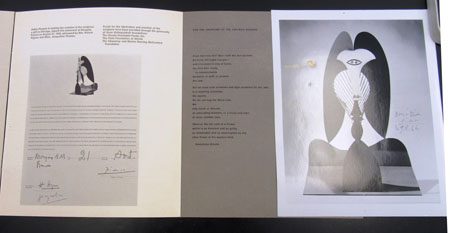

Original dedication program with images of statement and photograph signed by Picasso, 1966, and poem (center) by Gwendolyn Brooks. Photograph by CHM staff

Picasso declined the city’s payment of $100,000, stating that it was his gift to Chicago. The sculpture has since become a gathering place for all and an icon of the city. And while no one can say for sure what the sculpture resembles, it kicked off the city’s fifty year investment in and proliferation of public art.

Additional Resources

- See more images of Chicago’s Picasso

- Listen to Studs Terkel as he asks bystanders for their opinion on the new sculpture at the unveiling

- Learn more about Chicago’s Public Art Program

Zilah Harris has been working on the Museum’s latest collaborative initiative, the North Lawndale History Project, developed by Paul Norrington, president and founder of the K-Town Historic District Association, Inc. She is one of three North Lawndale Minow Fellows working with Peter T. Alter, the Museum’s historian and director of the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History. This is the second post in a series about the project.

Humans are essentially natural-born actors: every day we interact with our families, friends, and colleagues, and we show different sides of ourselves to each group. To conduct oral histories is to discover a certain part of someone’s personal life and their legacy.

For me, talking to people and trying to be comfortable around them can be a struggle. You learn a lot about a person when they have to talk about themselves. Getting people to open up and see them comfortable in their own skin is exciting and inspiring. So, conducting oral histories is actually pretty cool, even if you aren’t a dork like me. Oral histories are like a new day each time you do them; there is a routine but something different always comes about.

Dr. Clara Fitzpatrick, 2017. Photograph by Wynton Alexander

Dr. Clara Fitzpatrick is a woman who left her mark on this project and us. She radiates the energy of someone truly comfortable in their own skin. She grabs you by the hand and pulls you in not only with her smile but her stories about her life. Fitzpatrick is the daughter of Reverend J. M. Stone of Stone Temple Missionary Baptist Church, which is best known for its affiliation with Martin Luther King Jr.’s brief residency in North Lawndale and visit to the church.

Stone Temple Baptist Church, 2017. The Ten Commandments in Hebrew at the apex of the roof speak to the church’s origins as the First Romanian Congregation Synagogue. Photograph by Peter T. Alter

During the interview, she spoke of Dr. King’s visit to Chicago, specifically his time in North Lawndale and how it’s taken out of context and misinterpreted. Many people are under the impression that he lived there for several months, but Fitzpatrick says it was really about a week. She states, “Dr. King moved into that … house and stayed about two days and he was on his way out. See, I think we have a misunderstanding of Dr. King’s relationship to Chicago.” That was eye-opening to me. It goes back to interpreting history, which is written from people’s experiences and perspectives. Everyone has their own truth, and sometimes their truth can be believed and eventually considered fact.

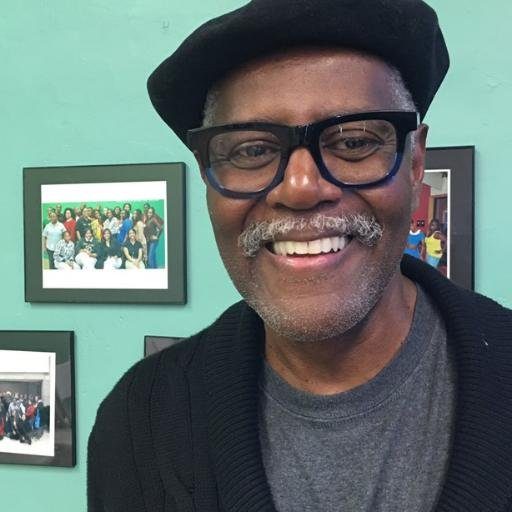

Howard Sandifer of the Chicago West Community Music Center

Howard Sandifer is another amazing soul who we had the privilege to interview. Sandifer is a very passionate and warm individual who takes a lot of pride in his people, community, and work. He is the executive director and cofounder of the Chicago West Community Music Center, a nonprofit organization that uses “education and training in the arts” to improve West Side communities. Sandifer spoke of his bright vision for the area: “You guys can do it, and I’m sure you will. This is the future, this is what we do; this is why we do what we do, because of you.” From this oral history, I saw how music truly is a strong force that can bring people together and spark a new sense of life in them. Music encourages people to be free and full of life and changes the standard for black kids. I truly enjoyed this interview. So, thanks, Mr. Sandifer.

Hear Dr. Fitzpatrick discuss Dr. King’s history with Chicago.

Listen to Mr. Sandifer talk of his dreams for the West Side.

Wynton Alexander has been working on the Museum’s latest collaborative initiative, the North Lawndale History Project, developed by Paul Norrington, president and founder of the K-Town Historic District Association, Inc. Wynton is one of three North Lawndale Minow Fellows working with Peter T. Alter, the Museum’s historian and director of the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History. The project supports the upcoming North Lawndale Sesquicentennial in 2019, which celebrates 150 years since Chicago annexed the West Side community. Consisting entirely of community stakeholders, the sesquicentennial committee is dedicated to fostering neighborhood pride by maximizing participation in celebrating North Lawndale’s 150 years of rich history and diverse cultures, while building for the future.

I have been working at the Chicago History Museum since June 15 and am a rising junior at North Lawndale College Prep High School (NLCP). I live in South Deering on Chicago’s Southeast Side. At NLCP, I play football, basketball, and run track and would like to attend Louisiana State University to major in robotics engineering or be a chef. With Zilah Harris and Ina Cox, I am conducting oral histories for the North Lawndale History Project.

Through these interviews, I have learned a lot about people and a lot more about North Lawndale. We interviewed current and former residents and people with significant connections to the community to find out information that is not otherwise recorded or documented. I love to ask questions and get deep into topics so that when it comes to doing interviews, I am well prepared and never worried.

Stone Temple Missionary Baptist Church, Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration, 2017. Photograph by Peter T. Alter

We have interviewed six people, one of whom was Dr. Clara Fitzpatrick. She was energetic, funny, and had a lot to talk about. Dr. Fitzpatrick also actually engaged us in conversation during the interview, which surprised me. She loved to talk about the relationship she had with her father, Reverend J. M. Stone, and perked up in her seat whenever his name came up. Reverend Stone was born in Georgia in 1906 and moved to Chicago in the 1930s. He was friends with Martin Luther King Jr.’s father.

From left: Wynton Alexander, Dr. Fitzpatrick, and Zilah Harris, 2017. Photograph by Ina Cox

In 1954, Reverend Stone moved his congregation from the South Side to the former First Romanian Congregation Synagogue on West Douglas Boulevard in North Lawndale. The building would be renamed Stone Temple Missionary Baptist Church, and starting in 1959 Reverend Stone would invite Martin Luther King Jr. to speak there on occasion. In August 2016, the Commission on Chicago Landmarks designated Stone Temple a landmark.

Listen to Dr. Fitzpatrick discuss the designation of Stone Temple as an official Chicago Landmark.

Dr. Fitzpatrick is a sweet lady. I feel since she is a teacher at Columbia College Chicago, she has even more knowledge to share and more things to bring to the table. I personally feel hers was among the best of the interviews we have done.