Latest Posts

On July 25, 1941, Mamie and Louis Till celebrated the birth of their only son Emmett at Chicago’s Cook County Hospital. Like many African Americans of the era, Emmett’s parents were part of the millions of Blacks who migrated north during what is now known as the Great Migration—Mamie from Mississippi and Louis from Missouri. The young couple met in Chicago and were married by the age of eighteen.

When Emmett was a teenager, like many migratory families of the time, he was sent to spend a summer visiting relatives still living in the South. A few days after arriving in Money, Mississippi, tragedy would strike when a then fourteen-year-old Emmett was accused of making overt gestures at Carolyn Bryant, a white woman, in her family’s store.

Around 2:00 a.m. on August 28, 1955, Bryant’s husband Roy and his half-brother John Milam kidnapped Emmett from his uncle’s house where he was staying. In the early morning, Emmett was brutally tortured, shot, and killed. His mutilated body was tied with barbed wire to a cotton gin fan and dumped in the Tallahatchie River. Three days later, Emmett’s badly decomposed body was found. The grotesquely disfigured corpse hardly resembled a human form.

Emmett Till and his mother Mamie Till, c. 1950. Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-48234. Mamie Bradley, the mother of Emmett Till, takes a last look at his open casket, Chicago, September 6, 1955. Photograph by Ralph Walters, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM, ST-17500641. © Sun-Times Media, LLC. All rights reserved.

When his body was returned to Chicago, his mother insisted on an open-casket funeral to “let the world see what I’ve seen.” Photographs published in the Chicago Defender and JET magazine, along with an account of the last days of Emmett’s life, were the first public recordings of the lynching. These images sparked outrage throughout the United States. Many historians attribute the reaction to these images as one of the catalysts that began the modern Civil Rights Movement.

In September 1955, an all-white jury acquitted Bryant and Milam, who confessed to the murder in 1956 after they were safe under double jeopardy laws. In 2017, it emerged that in a 2008 interview, Carolyn Bryant admitted to lying about what she had accused Emmett of doing to her. Unfortunately, Till would neither be the first nor the last person of color to lose their life or freedom on the basis of a lie conceived in racism.

In 2004, the Chicago History Museum acquired Franklin McMahon’s courtroom drawings of Bryant and Milam’s trial. With more than forty works ranging from simple pencil sketches to intricate ink-and-wash drawings, McMahon’s documentation is an invaluable record of what became one of the seminal moments of the modern Civil Rights Movement. See the drawings in the Fall 2005 issue of Chicago History magazine.

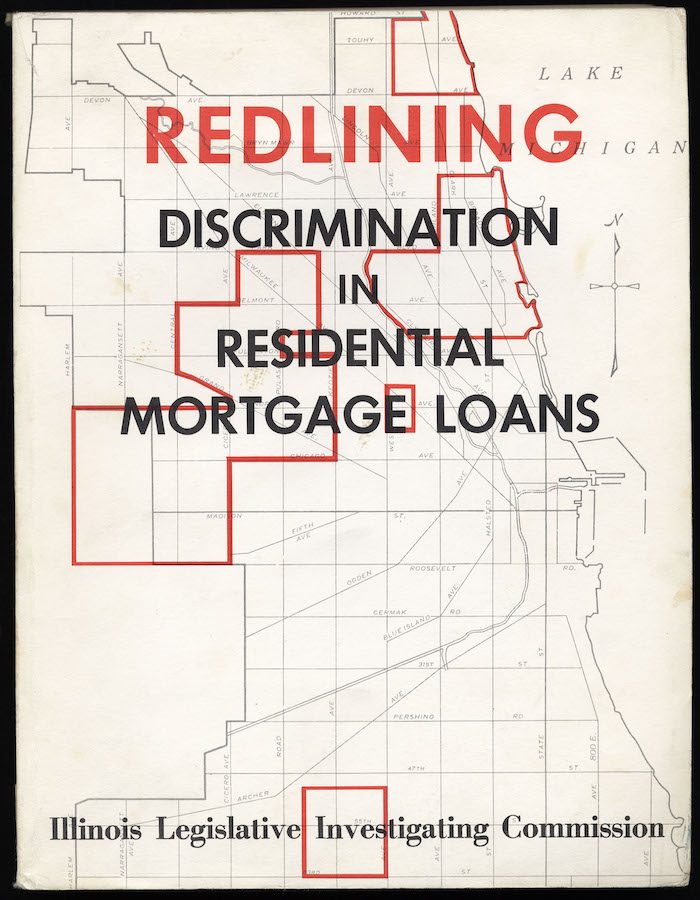

What is redlining? A form of discrimination. Simply put, it’s the practice of arbitrarily denying or limiting financial services to specific neighborhoods, generally because its residents are people of color or are poor. Like other forms of discrimination, it has inflicted long-lasting damage.

While discriminatory practices had long existed in the banking and insurance industries, the term came into use in the 1930s when the New Deal’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) instituted a redlining policy by developing color-coded maps of American cities that used racial criteria to categorize lending and insurance risks. New, affluent, racially homogeneous housing areas received green lines, while Black and poor white neighborhoods were often indicated by red lines denoting their “undesirability.”

In Chicago, the effects of redlining became obvious after World War II. Without bank loans and insurance, redlined areas lacked the capital essential for investment and redevelopment. As a result, suburban areas received preference for residential investment at the expense of poor and minority neighborhoods in the city. The relative lack of investment in new housing, rehabilitation, and home improvement contributed significantly to the decline of older urban neighborhoods and compounded Chicago’s decline in relation to its suburbs.

Redlining’s negative effects remained largely unrecognized by policymakers until the mid-1960s when the Fair Housing Act of 1968 was passed and then with the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act of 1975. Unsatisfied by the practical results of these laws, community activists in Chicago spearheaded further reform, leading the nation in identifying and addressing the redlining issue.

The cover of “Redlining: Discrimination in Residential Mortgage Loans,” a report by the Illinois Legislative Investigating Commission, 1975. CHM, ICHi-037471

The cover of “Redlining: Discrimination in Residential Mortgage Loans,” a report by the Illinois Legislative Investigating Commission, 1975. CHM, ICHi-037471

In the early 1970s, the Citizens Action Program, a crossracial group of community leaders from the South Side, developed a strategy of “greenlining” by asking residents to deposit savings only in banks that pledged to reinvest funds in urban communities. Chicago organizers were also instrumental in lobbying Congress to pass the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) in 1977, which required banks to lend in areas from which they accepted deposits. The law had limited effect until the National Training and Information Center in Chicago, led by Gale Cincotta, put public pressure on Chicago banks to lend to distressed neighborhoods. Cincotta’s group successfully negotiated $173 million in CRA agreements from three major downtown banks in 1984, settlements that served as models for other cities.

Additional Resources

- Learn more in the Encyclopedia of Chicago.

- A community activist from Chicago’s Austin neighborhood, Gale Cincotta was an expert on discrimination in mortgage loans and its effects in Chicago and other cities. Learn more about her work on issues of housing and employment in her interviews with Studs Terkel.

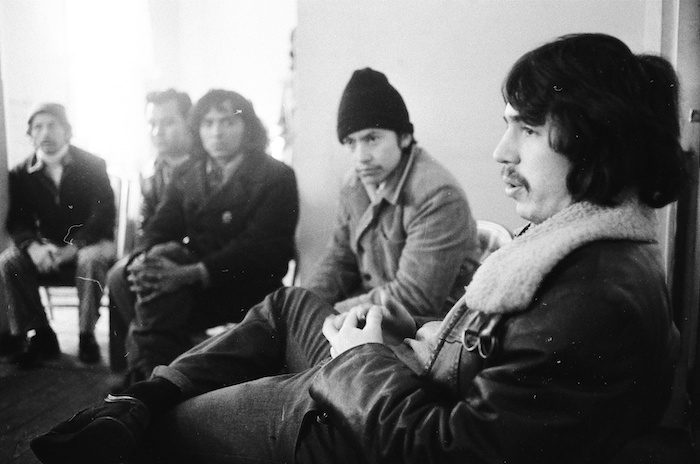

Rudy Lozano (foreground) at a Center for Autonomous Social Action meeting in 1975. ST-40001425-0011, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

On July 17, 1951, Mexican American political activist Rudy Lozano was born in Harlingen, Texas. Lozano and his family moved to Chicago in the early 1950s, and he spent his formative years in the Pilsen neighborhood on the near Southwest Side. Lozano’s activism began as a student at Carter Henry Harrison Technical High School (now Maria Saucedo Scholastic Academy), where he organized a walkout to protest poor school facilities and the lack of Latino representation in the curriculum.

After attending the University of Illinois Chicago, Lozano became a part of the group Centro de Acción Social Autónoma, Hermanedad General de Trabajadores (Center for Autonomous Social Action, General Brotherhood of Workers, or CASA). CASA worked to unionize noncitizen workers and provided them with welfare services and education to better know their rights as employees. Lozano also became the Midwest director of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union. His political work began in the Southwest Side’s 22nd Ward, where he registered Latine voters and tried to build unity between Latino and Black communities as he campaigned for Harold Washington, Chicago’s first African American mayor.

Lozano’s life was cut short on June 8, 1983, when he was murdered in his home. His memory lives on through the work of his sister, Emma, who created Pueblo Sin Fronteras (People Without Borders), an immigrant rights group, and in the Latino community in Chicago. The Rudy Lozano branch of the Chicago Public Library is located today in the Pilsen neighborhood.

Read more about Rudy Lozano at Digital Chicago History.

Made possible by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Digital Chicago History is a CHM website that showcases Lake Forest College’s Digital Chicago: Unearthing History and Culture project, a collection of multidisciplinary student and faculty research on Chicago’s history that explores diverse topics, such as music of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and the history of Haitian churches in Chicago, as well as student intern research conducted at CHM on the history of race in Chicago as part of the Humanities 2020 initiative. See all of these projects.

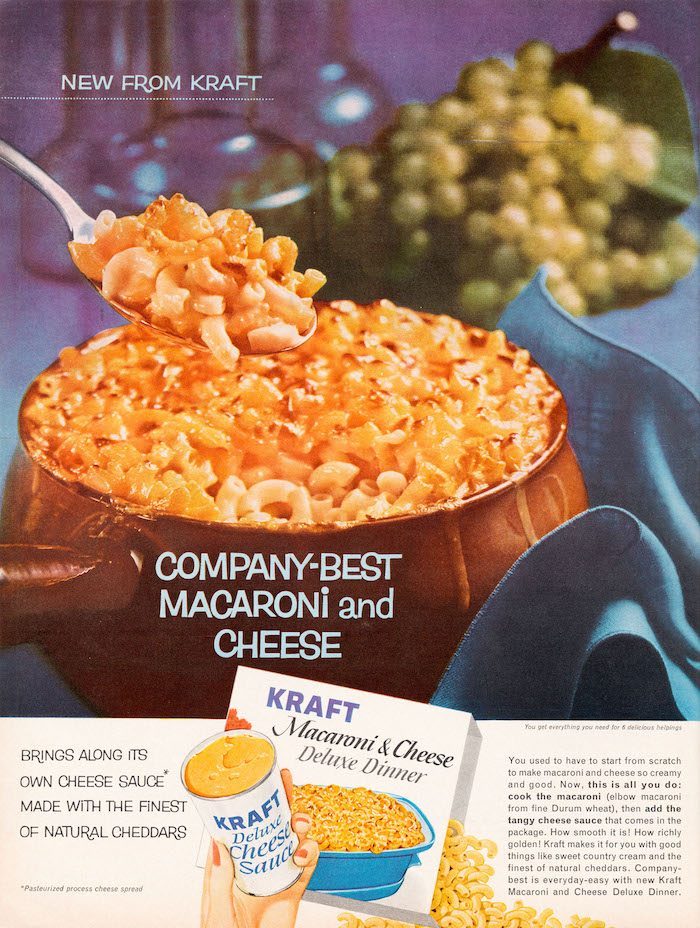

For National Mac and Cheese Day, we’re highlighting a local company whose name is synonymous with cheese—Kraft. Founded in 1903 by James L. Kraft, it started as a cheese-delivery business in Chicago, and within a few years, Kraft was producing cheese as well. By 1976, Kraft Inc. had about $5 billion in annual sales with nearly 50,000 employees around the world, including about 3,000 in the Chicago area. Starting in 2011, the company, then known as Kraft Foods, split into two publicly traded companies. The first, a snack food company called Mondelēz International, became the legal successor of the old Kraft Foods and recently moved from suburban Deerfield, Illinois, to Chicago. The second was the Chicago-based Kraft Foods Group grocery company, which later merged with Heinz to become the Kraft Heinz Company. In 2019, Mondelēz International had net revenues of approximately $26 billion, while Kraft Heinz earned about $25 billion in net sales.

One of its most popular products, Kraft macaroni and cheese was introduced in 1937. At just nineteen cents a box and easily prepared, the prepackaged product was a hit during the Great Depression and into World War II as rationing took place and working women had limited time at home. This advertisement from 1961 promotes Kraft’s new “company-best” Deluxe Dinner, which comes with prepared cheese sauce instead of the standard powder form.

Learn more about the history of food processing in Chicago in the Encyclopedia of Chicago. Read more.

Advertisement for Kraft Deluxe Macaroni & Cheese, 1961. Published in McCall’s. CHM, ICHi-040410

The Museum’s North & Clark Café is ready to welcome you again! A local gathering spot for both CHM visitors and neighborhood patrons alike, you can now enjoy our fresh-made menu offerings indoors, on the patio, or to go. We’re serving up Chicago-style hot dogs, all-day breakfast + coffee, and some of the best burgers in town! See the menus.

Let’s revisit an old Chicago favorite—Fritzel’s. Before air travel was common, Chicago was a popular stopping point for celebrities traveling by train between New York and Los Angeles, and there were certain restaurants where a star sighting was more or less guaranteed.

Located at State and Lake Streets in the Loop, Fritzel’s was founded in 1947 by Mike Fritzel and his business partner Joe Jacobson, who took over when Fritzel retired in 1953. The restaurant was known for not only the exceptional quality of its food, but also the nearly 100 items on its menu. In a 1967 interview with Chicago Tribune restaurant critic Kay Loring, Jacobson admitted, “It doesn’t make sense to have so many things on a menu. It’d be easier on the help, and we’d make more money if we cut it down. But it won’t be cut as long as I’m around.”

Fritzel’s at 201 North State Street, Chicago, April 12, 1959. CHM, ICHi-059848; Betty Hulett, photographer

At the height of its popularity in the 1950s and ’60s, the restaurant welcomed the biggest names in showbiz, sports, and Chicago politics. Among its regulars were comedian Phyllis Diller, singer Tony Bennett, and mayor Richard J. Daley. Members of Chicago’s baseball, hockey, and football teams frequented the establishment, as did many of the New York Yankees when the team was in town, including Whitey Ford, Mickey Mantle, and Yogi Berra.

However, a combination of factors led to Fritzel’s steady decline: in 1967 the massive fire at McCormick Place drastically reduced trade shows in Chicago for a period of time; the movie theaters in the Loop ceased showing family-friendly films, resulting in less foot traffic; and the increasing popularity of air travel meant fewer people traveling by train. By June 1972, the restaurant closed after being unable to break even for four weeks.

Trace Chicago’s evolution from meatpacking capital to foodie paradise through the Museum’s collection of historical menus and restaurant photographs. See more menus.

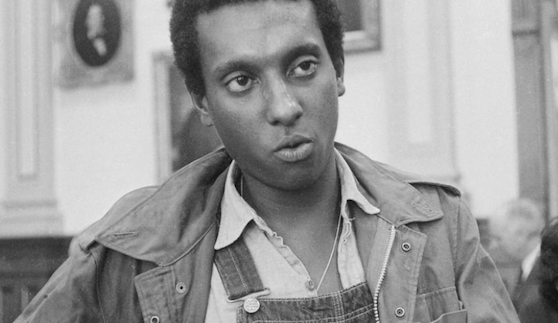

The architect of the Black Power movement who coined the term “Black power,” Stokely Carmichael was born on June 29, 1941. He was a leading voice during the Civil Rights Movement, first as a field secretary of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”) and later in the All-African People’s Revolutionary Party.<

Born in Trinidad and raised in New York City, Carmichael attended Howard University in Washington, DC, and graduated in 1964. While there, he organized several of the student-led sit-ins to desegregate lunch counters, movie theaters, and other establishments throughout the South that practiced racial segregation. Carmichael also participated in voter registration drives, including in Lowndes County, Alabama. Along with other SNCC members, he helped form the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO) as a third political party to challenge both Democratic and Republican parties in the county.

The LCFO adopted the image of a pouncing black panther as their symbol—one that would later be made famous by the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense founded by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in Oakland, California, in 1966 (with which Carmichael would later become affiliated). Moving toward a more pan-African liberationist philosophy, Carmichael moved to Guinea and changed his name to Kwame Ture. Carmichael/Ture died in 1998 from prostate cancer.

Stokely Carmichael, along with fellow SNCC members Charlie Cobb and Courtland Cox, spoke with Studs Terkel about civil rights, African Americans in politics, and the philosophy of the SNCC. Listen now.

Studs Terkel Radio Archive

Explore the Studs Terkel Radio Archive, which features more than 1,200 programs and interviews with the twentieth century’s most fascinating people. Browse the archive.

Born in Vicksburg, Mississippi, in 1954, Patrick Kelly was a self-proclaimed Francophile who mixed Parisian influence with the creativity and fashion sense of his female relatives, who often embellished store-bought garments with found objects. As a young adult, Kelly moved to Atlanta, where he sold recycled clothes, and he eventually moved to New York to study at Parsons School of Design. It was in Paris, during the late 1980s, that Kelly found his greatest success. He was the first American admitted to the Chambre Syndicale du Prêt-à-Porter, the governing body of French ready-to-wear.

Silk women’s suit, c. 1988. Patrick Kelly, France. Gift of Ms. Dorothy Fuller. 2008.174.1a-b. Photographs by by CHM staff

Kelly’s designs were exuberant and humorous, as seen in this silk women’s suit (c. 1988), and some of his most memorable garments used masses of plastic buttons, wild animal prints, and suggestive embroidery. But perhaps most notably, he was known for his potent referencing of folkloric racism in his work. Kelly used to give out handmade picaninny doll pins at his fashion shows. He deliberately grappled with the images of systemic racism that were widespread in his native Deep South and translated them into a blatant commercial statement. Kelly’s creations proved to be powerful and original contributions to the field of fashion, and he was a cult figure during his brief career that was prematurely and tragically ended by AIDS in 1990.

Patrick Kelly was in the headlines again in 2020 as the namesake of the The Kelly Initiative. Organized by editor Jason Campbell, creative director Henrietta Gallina, and writer Kibwe Chase-Marshall, the petition was a response from 250 Black fashion professionals to The Council of Fashion Designers of America’s antiracism efforts and a call on the trade organization to use its status to hold the industry accountable on hiring and promoting Black people. The initiative also seeks to start The Kelly List, an annual index of 50 Black industry professionals who will be given exposure and networking opportunities, and who will pledge to hire Black professionals throughout their careers.

Three-quarter right view of women’s jumper, 1987. Denim. Patrick Kelly Paris, France. CHM, ICHi-179042

See more items from our renowned Costume and Textiles collection, which has more than 50,000 artifacts dating from the eighteenth century to the present. Explore the collection.

In this blog post, CHM curatorial intern Brigid Kennedy recounts the life of Pearl M. Hart as part of a series in which we share the stories of local women who made history in recognition of our online experience: Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.

Pearl M. Hart is remembered by her family as being fond of boxing, her gun collection, and her car—a lavender Auburn—but she was known to much of the rest of the city as the “Guardian Angel of Chicago’s Gay Community” and as the lawyer who was devoted to defending immigrants and leftists amid anti-Communist fervor.

An undated portrait of Pearl Hart at her desk. CHM, ICHi-039673

Hart’s career began in 1912 when, at the age of twenty-two, she began taking evening classes at John Marshall Law School, where she would later teach. Just two years later she gained admission to the bar and became the first woman to serve as public defender in the Morals Court, which handled cases of adultery, prostitution, and child abuse (and eventually became the Women’s Court).

In 1937, Hart became a founding member and the first national secretary of the National Lawyers Guild (NLG), a progressive organization founded to advance civil liberties and the rights of trade unions and immigrants. Unlike the American Bar Association at the time, the NLG was racially integrated. Hart became a civil rights activist in the 1940s, and in 1948 became a member of the executive board and trustee of the bail fund of the Civil Rights Congress, Illinois chapter, which worked, among other things, against racially discriminatory housing laws and practices that enforced segregation. Hart also founded the Midwest Committee for Protection of the Foreign Born in 1947 to provide legal defense for noncitizens threatened with deportation and denaturalization by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS).

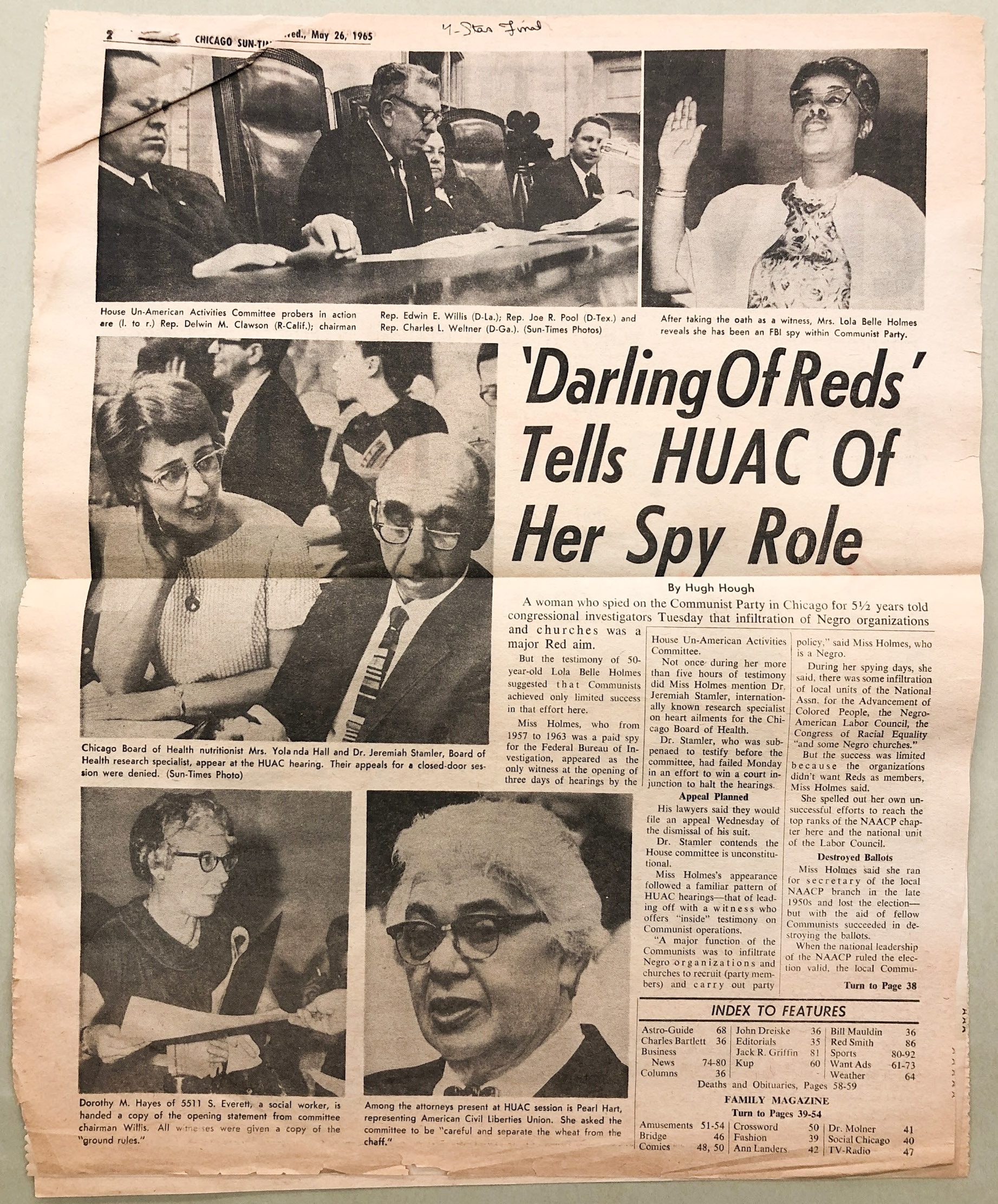

Despite the variety of work she did, Hart’s career became publicly defined by her defense of immigrants and leftists caught up in the mid-century Red Scare, also known as McCarthyism, and particularly those who were called to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) under threat of deportation and held without bail. Hart famously defended Chicagoans George Witkovich and James Keller, who were indicted for refusing to answer questions about their alleged affiliation with the Communist Party at their deportation hearings. The case eventually made it to the US Supreme Court, which ruled on May 19, 1957, that the attorney general could not seek evidence of Communist Party affiliation after a person had been ordered to be deported—a win for Hart.

Chicago Sun-Times article about some of Hart’s HUAC work. She is pictured at the bottom, center. May 26, 1965. Pearl Hart papers, Box 2, folder 1

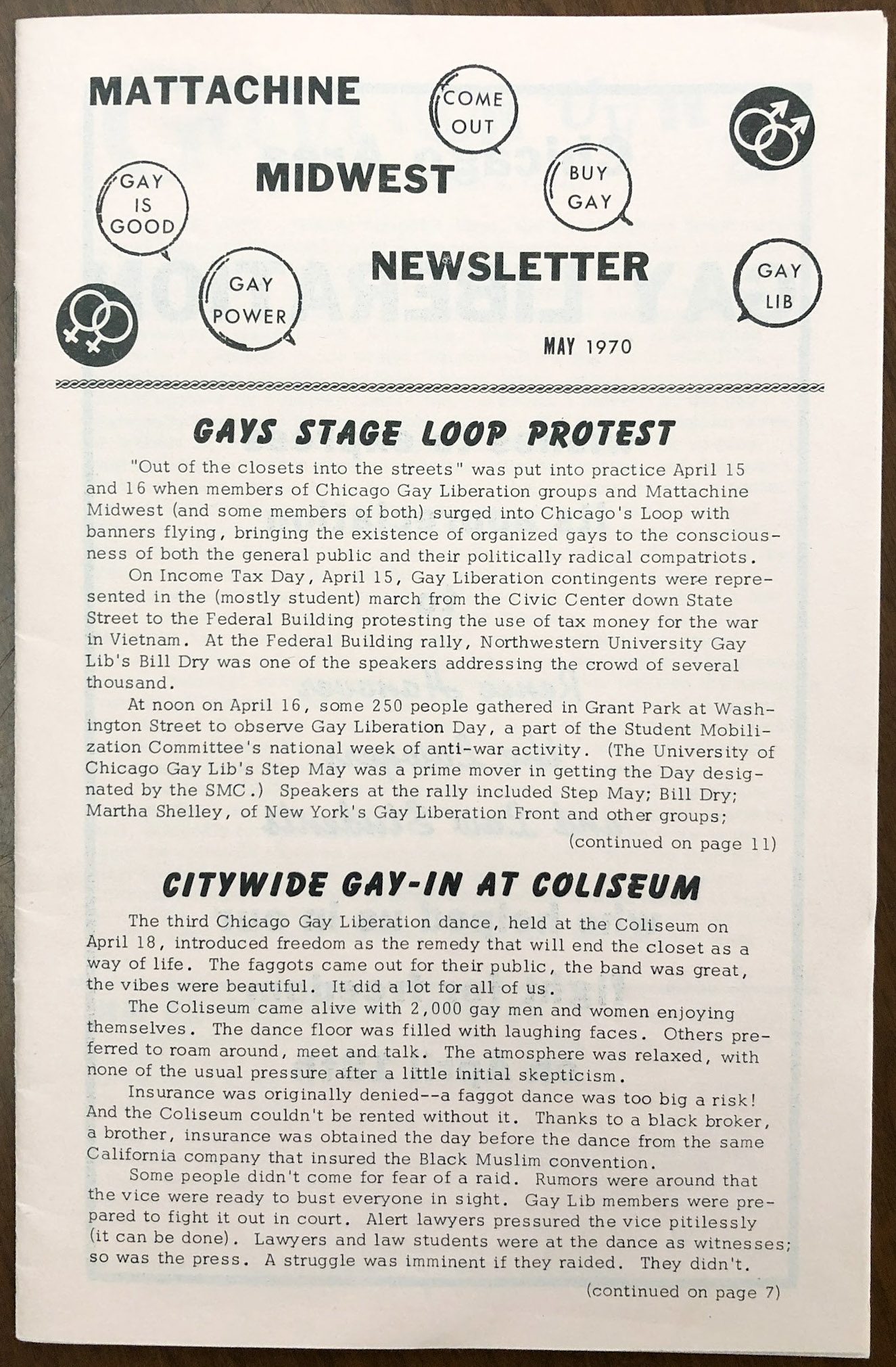

At the end of her career, Hart focused on securing civil rights for the LGBTQIA+ community in Chicago. She defended queer Chicagoans against police harassment and worked to garner support for anti-entrapment and right-to-privacy laws. In 1965, Hart cofounded a Midwest chapter of gay rights organization The Mattachine Society in response to Lavender Scare police entrapment schemes and raids on gay bars and increasingly common dismissals of queer people from jobs in the government and military. Hart utilized the newsletter for Mattachine Midwest to spread legal information and advice relevant to queer people. She served as legal counsel for the organization until her death in 1975.

Cover of a Mattachine Midwest newsletter, May 1970. Pearl Hart papers, Box 10, folder 7

Hart was herself a queer woman and lived with partners Blossom Churan and Bertha Isaacs for most of her life; she also had a relationship with author Valerie Taylor. She rarely discussed this part of her life publicly or with the rest of her family, but her enduring impact on the lives of queer Chicagoans is undeniable. Hart was one of the first people to be inducted, posthumously, into the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame in 1992, and she is one of the namesakes of the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives, the largest circulating library of gay and lesbian titles in the Midwest.

To learn more:

Legendary photographer Victor Skrebneski passed away on April 4, 2020. For this blog post, Nena Ivon, past president of the Costume Council of the Chicago History Museum, delved into her personal archive and reflects on her friend’s work with the Museum.

Victor Skrebneski had a varied and exciting association with the Costume Council of the Chicago History Museum through the years. During his half-century career, he was known for his striking images of models in advertisements and portraits of celebrities, but his work encompassed so much more than that. His extraordinary editorial photography graced the pages of Town & Country magazine, as well as numerous breathtaking books and catalogues. Victor’s eye for composition brought life to advertising campaigns for major retailers such as Saks Fifth Avenue and I. Magnin. His work was displayed in major exhibitions at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Contemporary Photography.

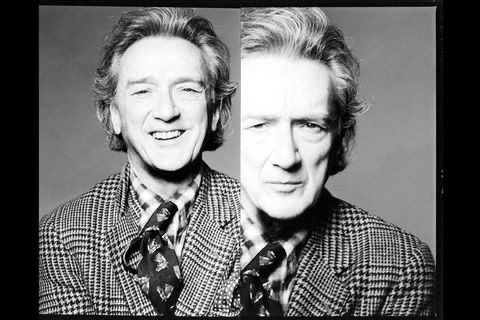

Undated self-portrait of Skrebneski. © Victor Skrebneski

Victor and the Costume Council were a perfect pairing—an iconic creator documenting an iconic costume collection. His contributions to the Costume Council and the Museum were extraordinary and leave us with breathtakingly exquisite images. He helped develop the Costume Council’s annual fundraiser—the legendary Donors’ Ball—through his unique invitations, serving on occasion as decor chair, and helping bring illustrious designers to headline the galas, such as Hubert de Givenchy in 1995.

Victor (left) looks on as Nena Ivon (standing) speaks with Givenchy and Bonnie Deutsch, a past Costume Council president, at the 1995 Donors’ Ball.

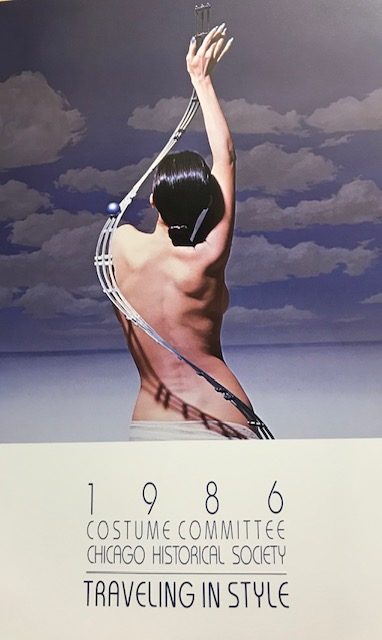

Here are two of examples of Donors’ Ball invitations featuring Victor’s photography.

The 1986 Donors’ Ball was presented at the opening of Northwestern Atrium Center (now 500 West Madison), which is connected to the Ogilvie Transportation Center.

Donors’ Ball 1990, one of my favorite invitations!

Victor, Bonnie Deutsch and Sugar Rautbord, Donors’ Ball Co-Chairs, flanking James Galanos, who received the first Designer of Excellence Award at the Donors’ Ball, Chicago, November 20, 1992. CHM, ICHi-069729

Geoffrey Beene (left) was honored in 1996 with the Costume Council’s Designer of Excellence Award. Pictured with him is past Costume Council president Lawrie Weed, Victor, and Ed Weed.

One of his extraordinary contributions to the Costume Council was a ten-page color photography spread in the October 1984 issue of Town & Country magazine, which featured seven Executive Board members in front of some of the Costume Collection’s spectacular pieces. Truly a memorable captured moment in time.

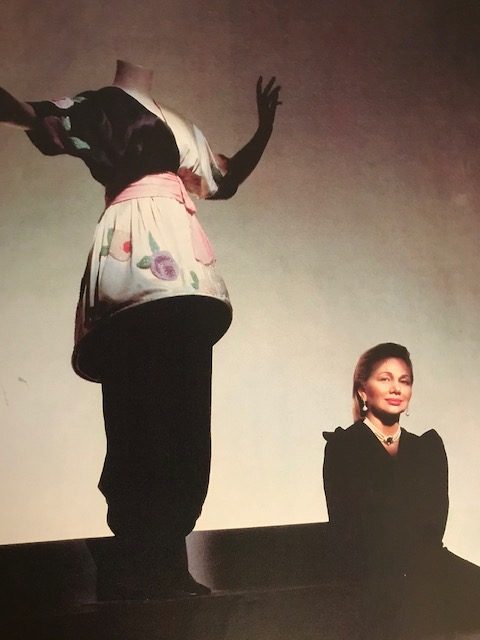

Beverly Blettner, past Costume Council president, with one of the crown jewels of the costume collection—Paul Poiret’s Sorbet! © Victor Skrebneski

In addition to his work with the Costume Council, Victor’s work can be seen when you visit the Museum. His portrait of Benjamin B. Green-Field is on display at the entrance of the gallery named after Green-Field. The milliner was a generous donor to the Museum, and the Costume Collection includes a huge assortment of his whimsical Bes-Ben hats.

Undated portrait of Benjamin Green-Field. CHM, ICHi-173662; Victor Skrebneski, photographer

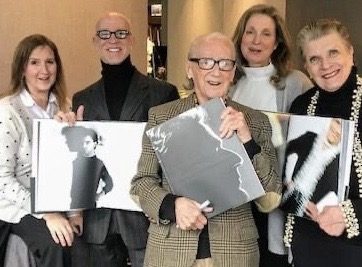

My last photograph taken with Victor was at a Fashion Group International Chicago event late last year. Pictured with us is Dennis Minkel, Victor’s longtime assistant, studio manager, archivist, and keeper of the flame. All of us are indebted to Dennis for his support of the Costume Council. We are holding the photographs of us that appear in Victor’s latest book, Skrebneski Documented. At the time of his death, Victor was working on two more books.

Dennis (second from left), Victor (center), and Nena Ivon (right), December 3, 2019.

It was one of the highlights of my life to not only work with this genius but to call him a dear friend for more than fifty years. His legacy will live on in the history of Chicago, the city he loved and called home.

CHM technical services librarian Elizabeth McKinley and cataloging and metadata librarian Gretchen Neidhardt outline how Research Center staff have been updating the language describing its holdings to reflect a viewpoint that is ethical, modern, and ultimately more humanizing.

For the past several months, Chicago History Museum librarians have been working behind the scenes to critically examine the language we use to describe our Research Center materials, including books, archives and manuscripts, and prints and photographs. Using the principles of critical cataloging, librarians have begun evaluating the keywords, subject headings, and summary descriptions used to identify items by and about marginalized and colonized groups, including African Americans, Indigenous peoples, and members of the disability community. This is only the start of an ongoing project that will work to address these and other group identities throughout the next several years.

CHM librarian Elizabeth McKinley (left) in the stacks during the CHM Members’ Open House, June 2019. Photograph by J. Keener Photography

Community consensus has inspired most of our changes, including empowered person-first language recommended by members of those communities. Our first changes were regarding the subject heading for “noncitizens,” previously “illegal aliens.” In some ways, this was an easy change, since the Library of Congress had proposed new and approved language, though an act of Congress prevented it from becoming official. Despite this, CHM has joined dozens of institutions in changing their public subject headings to reflect this more humanizing terminology.

Another example of more extensive changes involved the language of slavery, using P. Gabrielle Foreman’s community-sourced guide “Writing about Slavery/Teaching about Slavery: This Might Help.” Many of our collections with documents pertaining to slavery had descriptions transcribed directly from the card catalog. These cards, written decades ago, often quoted directly from the item itself. As one can imagine, some of this language sounded quite harmful. Enslaved people were not empowered or centered in any way; they were written about as if they were property. This is one of our many harsh historical truths, and in no way would we want to alter the original texts that discuss the brutality of the enslaver-enslaved person relationship. Slavery is an irrefutable part of American history, and we cannot deny its horrific effects. However, in describing an item, we can choose a description that ensures a more ethical and modern viewpoint that validates the personhood of someone who was enslaved.

CHM librarians Gretchen Neidhardt (center) and Elizabeth McKinley (second from right) present a display of Research Center materials, October 2019.

As we continue to consider the historical ramifications of colonization and marginalization in our language, our intention is not to erase histories, but to balance preserving a record of historical and institutional bias along with mitigating harm for current and future researchers. The Museum intends to converse and collaborate with a wide range of community members and organizations. Currently, we are finishing up changes to our Black and African American-related items and starting updates for materials related to the Indigenous and disability communities. We will build in periodic evaluation so that we can more frequently address necessary language changes.

An undated photograph of Research Center patrons at work. Photograph by CHM staff

We also recognize that communities are not monoliths—various members will have different preferences and experiences. We understand that language is fluid and forever changing, and this discussion is meant to be an ongoing and open dialogue. Read more about our critical cataloging work here. We welcome your thoughts or comments at research@chicagohistory.org. We’re excited to see where it takes us and hope to continue keeping you informed along the way.