Latest Posts

This year, Punxsutawney Phil saw his shadow on Groundhog Day, which (supposedly) means six more weeks of having to wear your winter coat. In this blog post, CHM costume collection intern Grace Koehler writes about a winter coat that represents retail, manufacturing, and fashion history.

At the turn of the 20th century, department stores played an important role in the economies of urban areas, especially Chicago. These stores originated in Europe and began cropping up in the United States during the 1830s. By the end of the century, they played a unique role in that both their target market and main workforce consisted of women. With the emergence of a middle class brought about by the Industrial Revolution making luxury goods and services more affordable, more women were able to stay home and maintain the household, relying on their husbands to provide. The new industries also enlisted the help of women as workers, and the idea of a woman having a job outside the home also became more acceptable. The department store offered employment for unwed women looking for a relatively “respectable” job in the city and offered a place to spend time (and money) for the married lady with a working husband and a disposable income.

Pedestrians viewing a Marshall Field & Company department store window display in the Loop community area of Chicago, 1910. DN-0008625, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

These stores offered a variety of goods at an unprecedented scale, especially ready-made clothing in fashionable styles for lower prices than those custom made for the wearer. These ready-to-wear garments in department stores and catalogues allowed more people access to rapidly changing styles, or at the very least offered them a chance to replace their worn-out wardrobes. Unlike today, however, the quality and attention to detail on these items was reduced relatively little compared to their bespoke counterparts. Though prices for these clothes were still higher than the cheap price tags on today’s fast-fashion items, those who made the clothing were similarly underpaid and overworked.

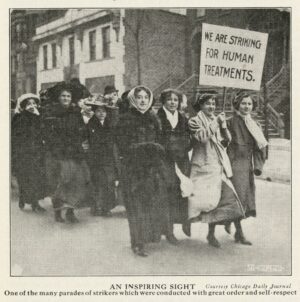

Garment workers on strike, Chicago, 1911. CHM, ICHi-067059

Instead of sourcing labor overseas as is common now, factories employed local working-class women and children, particularly immigrants. Unlike the women working in the department stores, these workers faced harsher conditions and rampant exploitation, particularly since unions and child labor laws were only just coming into play. They must have been efficient and highly skilled to have produced such quality goods at the rate needed to keep up with mass production and consumer demand.

Clothing made for department stores, such as this wool broadcloth coat (c. 1900), are impressive examples of goods made when mass-production was possible, but consumer expectations remained high. The coat has parallel lines meticulously stitched on its yoke and down its front and back, elongating its wearer’s silhouette. The faux double-breasted front is cut straight, and the back lightly fitted to accentuate the fashionable shape at the time and conveniently permitting it to fit wearers in a range of sizes. Large, round mother-of-pearl buttons and dusky brown velvet cross-stitched over the collar provide additional contrast and textural interest. The coat’s slim sleeves and simple, sleek cut stand in contrast to those from about a decade prior, which featured large, puffed sleeves and curve-hugging princess seams.

Left: Fashion illustration titled “Street Costume” by A. Izambard (St. Petersburg) in Coming Styles Designed by the Great Costumers of Europe, fall and winter 1896, published for Marshall Field & Co. by Rand, McNally & Co. CHM, ICHi-037454_h. Right: Sketch of coat on a wearer by Grace Koehler, 2024.

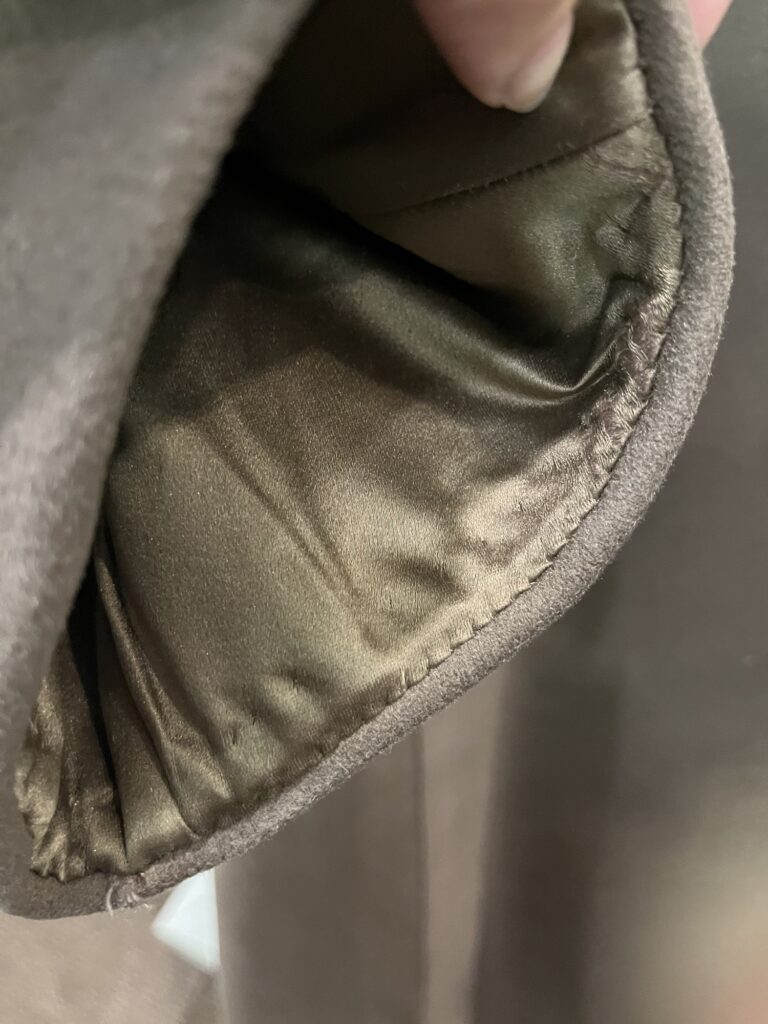

Closer inspection shows the thought put into the needs of the wearer, with a pocket neatly hidden in the self-fabric trim extending from the yoke as well as two breast pockets built into the front facing in a satin matching the fully lined interior. There is also a slit hidden in the back of the coat, also disguised by trim, perhaps to access a back skirt pocket?

The sleeves and hem appeared to be felled down with nearly invisible hand stitches.

On the inside of the coat at the nape is a label that appears to have been resewn by someone with less deft hands than the coat’s maker, turned upside down and backwards. It reads: “MAYER Chicago.” This coat was most likely purchased from the department store Schlesinger & Mayer.

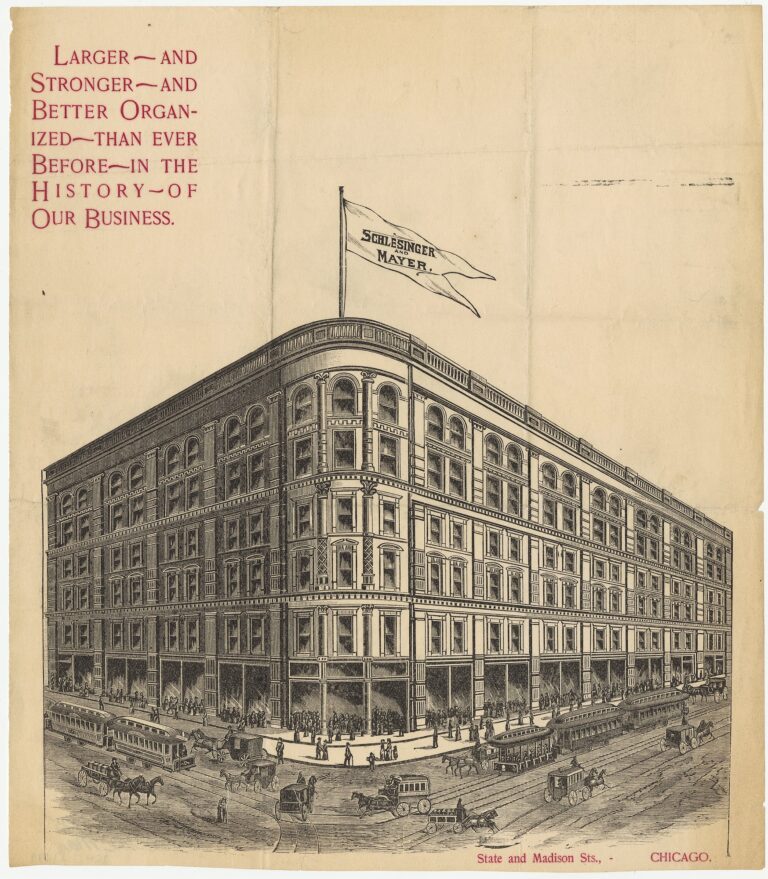

Advertisement for Schlesinger & Mayer, Chicago, 1873. CHM, ICHi-061679

Though the company had existed in Chicago since 1872, they commissioned architect Louis Sullivan to redesign their department store, which employed close to 2,500 people, at the corner of State and Madison Streets in 1899. After its completion in 1904, Schlesinger & Mayer could no longer afford to operate it, so they sold it to Carson Pirie Scott.

The coat’s owner was most likely a woman named Carrie Spooner Case, mother of its donor, Carolyn Case Norem. Carrie, with her husband Francis M. Case, was a Cook County resident around the time the coat was purchased. By the looks of her family photographs, she was an upper-middle or upper-class woman, making her an ideal customer at a department store. She may have visited the Schlesinger & Mayer storefront or flipped through their mail-order catalog until she found a coat that piqued her interest. Regardless, she certainly picked a practical, well-made coat that would last for years to come.

Claude M. Lightfoot (1910–1991) was an African American author, Chicago resident, political candidate, and member of the Communist Party USA’s national committee. In 1986, he donated a collection of his papers to the Chicago History Museum.

Portrait of Claude M. Lightfoot from Harold Marcuse, The Case of Claude Lightfoot, 1955 brochure. Public domain.

Born in Lake Village, Arkansas, in 1910, Claude Mark Lightfoot was raised by his grandmother until 1918 when the Lightfoot family moved to Chicago as part of the Great Migration. The Chicago Race Riots of 1919 stirred Lightfoot’s interest in politics and racial equality that would drive his life’s work.

In the wake of World War I, he joined Marcus Garvey’s Pan-Africanist movement, but he soon became convinced the ideology was unworkable. After a brief time at Virginia Union University—where he was expelled after the school discovered he did not have a high school diploma—he returned to Chicago in 1929.

Lightfoot joined the Democratic Party and helped found the Young Men’s Black Democratic Club in Chicago (1930). At this point in his political development, he was convinced that the answer to the plight of African Americans would be found in business enterprise. However, the Great Depression and the lack of progress and action regarding Black Americans’ financial and political standing convinced him otherwise.

In 1931, Lightfoot joined the Communist Party USA (CPUSA). In summer 1932, he attended a workers’ school organized by the Party, and later that year he ran for Illinois State Legislature on the Communist Party ticket and received 33,000 votes. By 1935, Lightfoot was a delegate to the Seventh World Congress of the Communist International in the Soviet Union.

After the Nazis declared war on the Soviets during World War II, Lightfoot enlisted in the US Army in 1941. The prejudiced treatment of both Communists and Black soldiers by the Army deepened Lightfoot’s belief in socialist government. He resumed his CPUSA activities upon his return home three years later. In 1946, Lightfoot prepared to run for the Illinois State Senate on the CPUSA ticket; however, his petition was successfully challenged by the Democratic Party—the Cold War had begun.

Undated photograph of Claude Lightfoot (right) with Jack Kling at an unknown location. CHM, ICHi-039210

On June 26, 1954, Lightfoot, then serving as the executive secretary of the Communist Party of Illinois, was arrested and charged with Communist Party membership and knowledge of the Party’s objectives “to teach and advocate the overthrow of the government of the United States by force and violence as speedily as circumstances would permit” as specified in the Smith Act of 1940. It was the first indictment under this clause, so Lightfoot’s case was a test case for both the defense and prosecution. Lightfoot believed the federal government targeted him to send a message to Black Americans to stay away from the Communists (and civil rights activities in general).

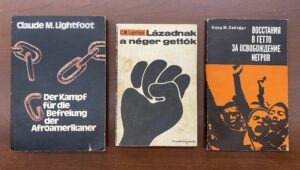

German, Hungarian, and Russian translations of Lightfoot’s Ghetto Rebellion to Black Liberation. Claude M. Lightfoot papers, Series 2, Box 2.

Lightfoot’s case was appealed all the way to the US Supreme Court, where Lightfoot was acquitted in 1964. That year, the Supreme Court also struck down the provision of the McCarran Act that withheld passports to CPUSA members. From 1964 until his death in 1991, Lightfoot worked for the CPUSA as a party officer and sought the advancement of Marxist-Leninist ideals. He wrote numerous books and articles about racism and communism and gave lectures around the world. In 1973, he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Rostock in Germany for his book, Racism and Human Survival: Lessons of Nazi Germany for Today’s World.

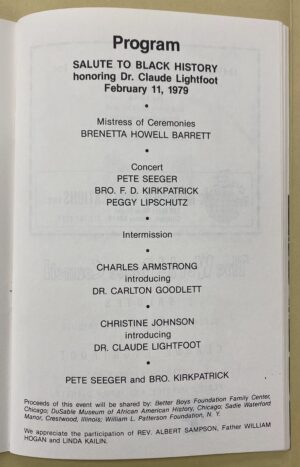

“Salute to Black history honoring Dr. Claude [M.] Lightfoot,” Feb. 11, 1979 program. Claude M. Lightfoot papers, Series 1, Box 1, Folder 23.

Today, the Claude M. Lightfoot papers [manuscript], 1950–85, n.d. (bulk 1969–85) can be accessed through the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit. The materials include correspondence, speech and manuscript notes, publicity information, reviews of his books, clippings and copies of Lightfoot’s newspaper columns in the Chicago Courier, and sound recordings of speeches by and about Lightfoot.

Lightfoot’s life, personal and professional, is chronicled in his autobiography, Chicago Slums to World Politics: Autobiography of Claude M. Lightfoot.

To mark the centennial of Maria Tallchief’s birth, CHM costume collection manager Jessica Pushor shares a bit about the prima ballerina’s life and a sampling of garments she donated to the CHM costume collection.

Maria Tallchief, Chicago, February 27, 1966. ADN-0000060, Chicago Daily News/Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; Edward DeLuga for Chicago Sun-Times, photographer

Maria Tallchief, famed ballerina, was born Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief on January 24, 1925, in Fairfax, Oklahoma, to Alexander Joseph and Ruth Tall Chief. Her father was a member of the Osage Nation, and her mother was Scotch-Irish. Tallchief was widely considered the first major prima ballerina to hail from the US and was the first Native American to hold that distinction. She danced with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo from 1942 to 1947 but is best known for her time with the New York City Ballet from 1947 to 1965 and served as prima ballerina.

Studio/publicity photograph of Maria Tallchief, 1947. Image 3, Larry Colwell Dance Photographs, Library of Congress.

During her dance career, Tallchief was married to choreographer George Balanchine from 1946 to 1952, then private pilot Elmourza Natirboff from 1952 to 1954. In 1955, while on tour in Chicago, she met Henry D. “Buzz” Paschen Jr., a construction company executive. In her Chicago Tribune obituary, she is quoted as saying that Buzz “was very happy, outgoing, and knew nothing about ballet—very refreshing.” They married the next year and in 1959 welcomed a daughter, Elise, Tallchief’s only child.

Undated photograph of Maria Tallchief, teaching, with a dancer at the Lyric Opera of Chicago. CHM, ICHi-036422

After Tallchief retired from dancing in 1965, she was appointed ballet director at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1971, a position she held for two decades, and was the founder and co-artistic director of the Chicago City Ballet (1981–87).

Maria Tallchief (center) speaks with two dancers at a Chicago City Ballet performance at St. James Cathedral Plaza, 65 E. Huron St., Chicago, June 10, 1981. ST-12002371-0037, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Maria Tallchief had a long affiliation with the Museum, as she donated a total of 17 ensembles to the costume collection beginning in 1974 until 1992.

Dress, 1947. Wool crepe and silk velvet. Christian Dior, France. Gift of Mrs. Henry D. Paschen. CC.1974.483

This dress by Christian Dior is the Museum’s only garment from the Corolle line, Dior’s historic first haute couture Spring-Summer 1947 collection, the opening of which Tallchief attended. Tallchief purchased this dress—titled “Maxim,” after Dior’s favorite restaurant—and wore it when she received the 1953 Woman of the Year award from President Dwight D. Eisenhower. This dress was also the first donation Maria Tallchief made to the Chicago History Museum’s costume collection, and one of two Diors she donated.

Cocktail dress, c. 1954. Silk faille. Christian Dior, France. Gift of Mrs. Henry D. Paschen. 1980.142a-b

The other Dior is this cocktail dress, which still has its import tax seal attached to the interior side seam, and is the only Dior dress in the Museum’s collection that still has that seal.

Evening ensemble, c. 1984. Silk crepe and satin, sequin, glass beads. James Galanos, United States. Gift of Mrs. Henry D. Paschen, 1990.665.1a-c. Left: ICHi-063887, right: ICHi-063889

In 1990, Tallchief made her largest donation to CHM’s costume collection—12 garments by a variety of fashion designers including Mary McFadden, Geoffrey Beene, Zandra Rhodes, Bill Blass, and this ensemble by American fashion designer and couturier James Galanos. Designed in 1984, this three-piece evening ensemble of black silk chiffon and silk satin features shoulders and arms trimmed with red sequins and bugle beads, a full-length wrap skirt, and a separate cummerbund that wraps around the waist and hips. Tallchief purchased it at Bergdorf Goodman in New York.

For her contributions to American ballet, Tallchief was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1996, and in 1999 she received the National Medal for the Arts and the Theodore Thomas History Maker Award for Distinction in Performing Arts at the Chicago History Museum’s yearly Making History Awards. Maria Tallchief died on April 11, 2013, the age of 88. She was posthumously inducted into the National Native American Hall of Fame in 2018.

Additional Resources

- Read “Creating a Dance: Interviews with Bruce Graham and Maria Tallchief,” Chicago History (Spring 2000)

- View more items in the CHM Costume and Textiles Collection

On the 52nd anniversary of the US Supreme Court decision on Roe v. Wade, Elisabeth Heissner, manager of visitor acquisition & engagement, and Hannah Johnson, member relations manager, share about the Jane Collective and their work in the years before Roe providing illegal but safe abortions.

Fifty-two years ago, on January 22, 1973, the US Supreme Court issued their decision on Roe v. Wade, declaring that the Constitution protected a right to abortion. The case was argued on the grounds that the Fourteenth Amendment provides a fundamental right to privacy, which includes an individual’s decision to abort their pregnancy. However, before Roe, access to safe abortions was difficult to obtain in most of the country, including Illinois. So, in the absence of safe and legal abortions, in the late 1960s a Chicago-based group named the Jane Collective emerged. The Jane Collective or, simply, “Jane,” was founded by Heather Booth, a University of Chicago student with ties to the Civil Rights Movement and the 1964 Freedom Summer project in Mississippi. Jane relied on underground methods and grassroots planning to coordinate abortions for women who contacted them.

In a 1996 interview with Studs Terkel, Laura Kaplan, former Jane member, discussed her book The Story of Jane: The Legendary Underground Feminist Abortion Service (1995). Between 1969 and 1973, Jane provided an estimated 11,000 safe abortions, counseled women, and distributed reproductive education resources, at the risk of the members’ own safety and reputations. The group was born out of social movements of the late 1960s, particularly the Civil Rights Movement and the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union (CWLU), and attracted between 120 and 140 likeminded members.

Hand-painted wooden sign that reads “Chicago Women’s Liberation Union,” c. 1975. CHM, ICHi-179843

How does one provide a safe, but illegal, abortion?

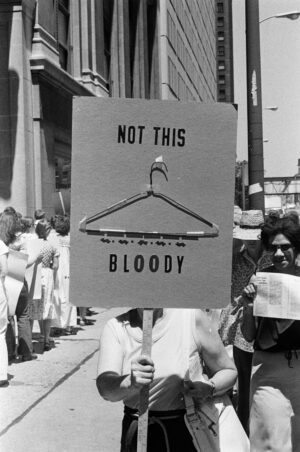

Members of the Abortion Rights Association of Illinois picket in the Loop in favor of vetoing state bill HB333, which would reaffirm a ban on abortion funds, Chicago, July 7, 1977. ST-19000044-0019, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Surprisingly, the answer came from a man with no formal medical training. The founding Jane members found a resource in a “Dr. Kaufman,” who operated out of motels in west suburban Cicero, Illinois. Dr. Kaufman, or “Nick,” as he is referred to in Kaplan’s book, entered into an agreement with Jane to perform abortions for the promise of steady business. Jane secured clients through word of mouth; women seeking abortions called a general line to leave a message for “Jane,” and would then be counseled by a member who returned their call. Members would use their apartments as “fronts” for client check-in. After visiting “the front,” the client would be driven to a second apartment for the abortion, then return to the “front” post-procedure. In the weeks following, a Jane member would follow up with the patient to discuss her recovery.

When Nick’s lack of medical training was discovered, Jane members began assisting with the procedure and gained the confidence to perform abortions themselves. Eventually, the Collective was discovered, and several members were arrested. Legal proceedings were delayed until Roe v. Wade came before the Supreme Court. After the Roe decision, the charges against the arrested members were dropped, and Jane dissolved.

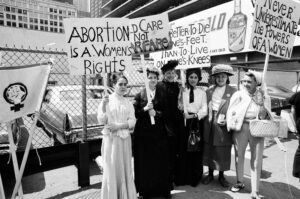

Women march down State Street and meet for a rally at the Civic Center (Richard J. Daley Plaza), 50 West Washington Street, for the first women’s liberation march since 1916, where women supported reproductive rights, child care, and equal pay, Chicago, May 15, 1971. ST-20003470-0028, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

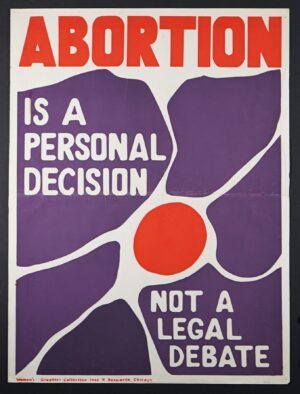

After the overturning of Roe with the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) decision, many have noted similarities in the current state of reproductive freedoms to that of the 1960s and ’70s. Recently, the Museum has drawn comparisons to the social and civil movements of this era in the exhibition Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s–70s, which features a pro-choice poster made by the CWLU.

“Abortion is a Personal Decision, Not A Legal Debate,” designed by the Chicago Women’s Graphics Collective, 1972. Photograph by CHM staff.

Through Civic Season, a celebration that spans from Juneteenth to Independence Day, and our current exhibitions, the Chicago History Museum urges visitors to stay civically engaged and be curious about the landscape of our democracy, including judicial decisions. Being an engaged citizen does not always mean starting your own underground abortion service; as evidenced in Designing for Change, all forms of civic engagement hold importance. Though the climate of America is ever-changing, your involvement in democracy is a constant in shaping our collective future.

Additional Resources

- Learn more about Chicago History Museum’s annual Civic Season in partnership with Made By Us.

- Learn more about The Jane Collective from founder Heather Booth.

- Listen to the Chicago History Museum’s full recording of Studs Terkel’s interview with Laura Kaplan.

- Read more about the CWLU Page on Encyclopedia of Chicago.

Sources

- Discussing the book The Story of Jane: The Legendary Feminist Abortion Service with the author and former member of Jane, Laura Kaplan, with Studs Terkel, Studs Terkel Radio Archive, January 22, 1996.

- Laura Kaplan, The Story of Jane: The Legendary Feminist Abortion Service (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

- K. K. Ottesen, “Meet the Woman Who Started an Underground Abortion Network in the 1960s.” The Washington Post, August 23, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/magazine/2022/08/23/abortion-janes-roe-vs-wade-supreme-court/.

- Margaret Strobel, “Chicago Women’s Liberation Union,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, accessed November 19, 2024, http://encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1372.html.

We’d like to extend a special thanks to You’re Wrong About podcast host Sarah Marshall and guest Moira Donegan for sparking our interest in this topic with their episode “The Jane Collective with Moira Donegan.”

CHICAGO (January 9, 2025) – Chicago History Museum (CHM) is thrilled to announce it has received a $2.5 million grant from Lilly Endowment Inc. through its Religion and Cultural Institutions Initiative. The grant will be used over the next several years to support the second phase of CHM’s Chicago Sacred Initiative through programming, education, digital initiatives, and a forthcoming exhibition centered on everyday stories of places of ritual, memory, memorial and belief.

“We are honored to continue our relationship with Lilly Endowment,” says Donald Lassere, Museum President and CEO. “This initiative is designed to foster public understanding about religion and lift up the contributions that people of all faiths and diverse religious communities make to our greater civic well-being.”

“The shifting religious landscape highlights the need for our practice as a museum to uplift sacred, spiritual and community expressions beyond singular religious traditions,” says Rebekah Coffman, curator of religion and community history. “With so many rich sacred legacies present throughout Chicago, this work seeks to bring its many diverse communities into dialogue with the past, present and each other to envision what the future of urban religion can be in cities like Chicago.”

In 2019, Lilly Endowment launched the Religion and Cultural Institutions Initiative. Its aim is to support museums and other cultural organizations as they strengthen their capacity to provide fair, accurate and balanced portrayals of the role religion has played and continues to play in the United States and around the world. Chicago History Museum received a grant through the initiative’s first round of funding in 2021. That grant enabled the Museum to establish the Chicago Sacred Initiative through the creation of a new permanent role, curator of religion and community history, and the Lilly Collections Fellowship, a program for early career archivists in sacred and community-based collections.

“The United States is widely considered to be one of the most religiously diverse nations today,” said Christopher L. Coble, Lilly Endowment’s vice president for religion. “Many individuals and families trust museums and other cultural institutions and visit them to learn about their communities and the world. We are excited to support these organizations as they continue to develop their capacities to help visitors understand and appreciate the diverse religious beliefs, practices and perspectives of their neighbors and others in communities around the globe.”

###

ABOUT THE CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

The Chicago History Museum is situated on ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi people, who cared for the land until forced out by non-Native settlers. Established in 1856, the Museum is located at 1601 N. Clark Street in Lincoln Park, its third location. A major museum and research center for Chicago and U.S. history, the Chicago History Museum strives to be a destination for learning, inspiration, and civic engagement. Through dynamic exhibitions, tours, publications, special events and programming, the Museum connects people to Chicago’s history and to each other. The Museum collects and preserves millions of artifacts, documents, and images to assist in sharing Chicago stories. The Museum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chicago Park District on behalf of the people of Chicago.

ABOUT LILLY ENDOWMENT INC.

Lilly Endowment Inc. is an Indianapolis-based private foundation created in 1937 by J.K. Lilly, Sr. and his sons Eli and J.K. Jr. through gifts of stock in their pharmaceutical business, Eli Lilly and Company. Although the gifts of stock remain a financial bedrock of the Endowment, it is a separate entity from the company, with a distinct governing board, staff and location. In keeping with the founders’ wishes, the Endowment supports the causes of community development, education and religion. Although the Endowment maintains a special commitment to its founders’ hometown, Indianapolis, and home state, Indiana, it also funds programs throughout the United States, especially in the field of religion. While the primary aim of its religion grantmaking focuses on strengthening the leadership and vitality of Christian congregations in the United States, the Endowment also seeks to foster public understanding about religion and lift up in fair, accurate and balanced ways the contributions that people of all faiths and diverse religious communities make to our greater civic well-being.

CHM director of research & access Ellen Keith shares about the most requested research collections from the Abakanowicz Research Center in 2024.

In 2024, staff at the Abakanowicz Research Center retrieved nearly 900 linear feet of archival material and more than 500 distinct collections. Here are the top five most requested in 2024, and if you followed what was requested in 2022 and 2023, no surprises for the top collection.

#5 – Glessner family papers [manuscript], 1851–1960, bulk 1864–81

Chicagoans now consider the Gold Coast the city’s most high-end neighborhood, but in the late 19th century, the most affluent neighborhood was Prairie Avenue, south of Roosevelt Road. One of the still extant homes there, now a house museum, is Glessner House. At the time, the socially prominent Glessner family was on par with the Armours and the Pullmans.

The J. J. Glessner residence at Prairie Avenue and 16th Street, Chicago, c. 1905. CHM, ICHi-068071; Charles R. Clark, photographer

#4 – Business and Professional People for the Public Interest records [manuscript], 1938–2003

The BPPPI (now Impact for Equity), a public interest law firm, most notably sued the Chicago Housing Authority on behalf of Dorothy Gautreaux for the placement of public housing in low-income, African American neighborhoods. Learn more in Alexander Polikoff’s Waiting for Gautreaux: A Story of Segregation, Housing, and the Black Ghetto.

Representatives of the BPPPI hold a press conference regarding the Red Squad at the Executive House Hotel, 71 East Wacker Drive, Chicago, January 5, 1977. Dr. Marvin Rosner is speaking at the podium, and Albert E. Jenner Jr. sits to the left of the podium. ST-60002106-0062, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

#3 – Studs Terkel papers [graphic, manuscript], 1944–2008, bulk 1944–85

Louis “Studs” Terkel (1912–2008) was a well-known radio host, author, oral historian, and the Chicago History Museum’s first Distinguished Scholar-in-Residence. He published the oral history compilation Division Street: America in 1966, beginning a long career of conducting and publishing oral histories including Hard Times (1970), Working (1974), and American Dreams: Lost and Found (1980). Look for the upcoming podcast, Division Street Revisited, and in the meantime, check out digitized radio programs at the Studs Terkel Radio Archive.

Studs Terkel interviews Swedish opera singer Birgit Nilsson in a recording studio, Chicago, c. 1960. CHM, ICHi-025638; Stephen Deutch, photographer

#2 – Chicago Yacht Club records [manuscript], 1869–1999

Founded in 1875, Chicago’s oldest yacht club has sponsored the Race to Mackinac since 1898. This manuscript collection includes correspondence, membership lists, various announcements of activities, programs, and race results, as well as architectural drawings of its Belmont Harbor station.

The Chicago Yacht Club’s Monroe Station, 400 E. Monroe St., Chicago, April 26, 1985. ST-20002700-0014, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

#1 – Chicago Police Department Red Squad and related records [manuscript], c. 1930s–1986, bulk 1963–74

The winner and still champion! As these are records of surveillance by the CPD of suspected “subversives,” which included anarchists, suspected communists, labor organizers, and reform organizations, this collection is governed by a court order.

CHICAGO (January 2, 2025) – The Chicago History Museum is thrilled to offer numerous Illinois resident free days to kick off 2025, giving visitors the opportunity to explore the city’s rich history. Free days will be on the following dates: January 20–24 and 28–31, and Tuesday–Friday every week in February, as well as Presidents’ Day. Learn more and purchase tickets here.

“The Chicago History Museum is a must-visit destination for anyone interested in the history of this great American city,” said one recent visitor. “Whether you’re interested in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the city’s role in the Civil Rights Movement, or the rise of Chicago’s many famous politicians, you’ll find something to pique your interest and leave with a newfound appreciation for Chicago’s rich and diverse history.”

In addition to upcoming free days, a series of programs will take place at the start of the new year, including events on Martin Luther King Jr. Day and Presidents’ Day. Learn more about upcoming Museum events here.

Closing Soon

City on Fire: Chicago 1871

Closing January 26, 2025

Designed for families, City on Fire: Chicago 1871 explores the impact the fire had on the city and its people. The exhibition takes visitors through events and conditions that led to devastation and recovery and sheds light on what life was like in 1871. Following the detailed path of the fire, from the O’Learys’ barn north and east through the city, visitors are immersed in the destruction of the fire and the decisions that civilians were faced with as they fled danger. Learn more here.

During the month of January, the Museum will be screening WTTW’s The Great Chicago Fire: A Chicago Stories Special in the afternoon. The film brings to life this seismic event as never before, using vivid animations, elaborate recreations, and interviews with historians and the descendants of eyewitnesses. The screenings are included in Museum admission.

On View

Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s–70s

Chicago activists in the 1960s and ’70s used design to create powerful slogans, symbols and imagery to amplify their visions for social change. See more than 100 posters, fliers, signs, buttons, newspapers, magazines and books from the era, expressing often radical ideas about race, war, gender equality and sexuality that challenged mainstream culture of the time. Learn more here.

Dressed in History: A Costume Collection Retrospective

Featuring 70+ rarely seen objects, from glamorous gowns and sharp suits to housedresses and sneakers, the exhibition explores how clothing captures material, social and changing cultural values throughout history. The exhibition celebrates 100 years of an incredible collection and the donors, curators and staff who have shaped it. Learn more here.

Injustice: The Trial for the Murder of Emmett Till

In 1955, the murder of Emmett Till, a Black teenager from Chicago, and the subsequent criminal trial in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi, attracted international attention and sparked the Civil Rights Movement. Injustice: The Trial for the Murder of Emmett Till begins with photographs of a joyful Emmett in life and of his funeral attended by thousands. The trial proceedings are then shared through courtroom sketches by Franklin McMahon. These drawings give a visual account of a trial that amplified the inequities Black Americans face within the US court system, including a lack of equal protection under the law. Learn more here.

###

ABOUT THE CHICAGO HISTORY MUSEUM

The Chicago History Museum is situated on ancestral homelands of the Potawatomi people, who cared for the land until forced out by non-Native settlers. Established in 1856, the Museum is located at 1601 N. Clark Street in Lincoln Park, its third location. A major museum and research center for Chicago and U.S. history, the Chicago History Museum strives to be a destination for learning, inspiration, and civic engagement. Through dynamic exhibitions, tours, publications, special events and programming, the Museum connects people to Chicago’s history and to each other. The Museum collects and preserves millions of artifacts, documents, and images to assist in sharing Chicago stories. The Museum gratefully acknowledges the support of the Chicago Park District on behalf of the people of Chicago.

Bes-Ben was best known for fantastical hats, but what did the man who created them wear? In this blog post, CHM costume collection intern Penelope Ham writes about Benjamin Benedict Green-Field’s personal style.

While milliner Benjamin Green-Field (1898–1988), cofounder of the Bes-Ben hat shop, is renowned for his unconventional hats, his equally iconic personal wardrobe is not as well-known. In addition to the nickname of “The Mad Hatter of Chicago,” Green-Field was also described as flamboyant, extravagant, and a “connoisseur of art and design.”

Benjamin Green-Field flanked by Barbara Lowe (Mrs. A. Loring Rowe, left) and Hanchen Stern (Mrs. Gardner H. Stern, right) at the opening reception of the exhibition The Whimsical World of Bes-Ben Hats at the Chicago Historical Society, April 14, 1976. CHM, ICHi-069732

He loved to travel and made more than 59 trips around the world in his lifetime. He was fascinated with life overseas and wrote in great detail about what he saw during his travels. Green-Field’s deep interest in clothing and textiles was greatly influenced by his travels, and his wardrobe consisted largely of custom suits made from fabrics he would buy abroad.

Suit, c. 1975. Silk. Gents Tailor Alberts, India. Gift of Mr. Benjamin B. Green-Field. 1978.163a-c. Top: CHM, ICHi-170032. Bottom: CHM, ICHi-170037

The purpose and conventional use of the fabric was of little importance to him, and some, such as the jacket below, were made of upholstery fabrics. One newspaper in Capri knew him as “the man of twenty shirts,” and he was followed by the press everywhere he went due to his extravagant outfits and his love for being photographed.

In addition to elaborate patterns, his suits also provide a number of other eye-catching, intricate details. The jacket and pants contain many pockets, on both the inside and outside of the garments, as well as extra pleating in the back, almost evocative of a skirt.

Man’s suit of multicolored tapestry fabric. 1989.562.1.82a-c.

Pictured above is one of Green-Field’s iconic suit jackets. In addition to many pockets, this jacket is also collarless and would have been paired with an equally showy shirt or tie.

Here is a back view of the same jacket. On the sides, some of the skirt-like pleating can be seen.

The jacket’s interior has an equally lavish lining, another hallmark of Green-Field’s suits. In some cases, he opted for a simpler fabric on the outside. The lining would not be seen by the public and therefore was just for him to enjoy.

Although the Bes-Ben shop closed its doors for good in 1978 following the decline of hats in fashion, Green-Field’s legacy lives on today through his vibrant clothes, unique designs, and spectacular sense of style. You can learn more about Benjamin Benedict Green-Field and see a selection of Bes-Ben hats in our exhibition Chicago: Crossroads of America.

Additional Resources

- View photographs of select Bes-Ben hats from our Costume and Textiles Collection

- Read our blog post “A Perfect Hat for Fall“

- For further reading, try Elizabeth Jachimowicz’s book Bes-Ben: Chicago’s Mad Hatter

- Learn about the Benjamin B. Green-Field Foundation, which strives to improve the quality of life for children and the elderly in Chicago.

As part of her work on our upcoming exhibition Aquí en Chicago, CHM curator of civic engagement and social justice Elena Gonzales has been examining how we can find Latin American heritage in unexpected places that connect us to unexpected allies and unknown cousins.

Latin American heritage is broad, and our tidy ideas about what this “region” is are often incomplete. Here is a brief look at a few examples that help us understand the concept of a global Latin America, where colonizer, language, and geography do not neatly determine the boundaries of the region.

Haiti

Chicago’s first non-Native permanent settler, Jean Baptiste Pointe DuSable (d. 1818), was Haitian. Our Latine history starts before Chicago was even a city.

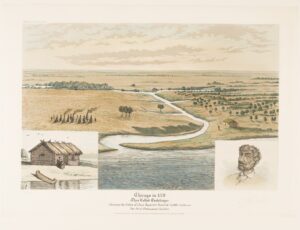

Engraving titled “Chicago in 1779,” depicting the cabin of Jean Baptiste Pointe DuSable and his portrait, c. 1926–32. Published by A. Ackermann & Sons Inc. CHM, ICHi-005623; Raoul Varin, artist

The first stop for Christopher Columbus in the Americas was La Navidad in what is now Haiti. There, Columbus encountered Taíno people, part of the Arawak group of Indigenous people, who Europeans also encountered in what would become Puerto Rico. Today, the Taíno word “Boricua” refers to a Puerto Rican identity with a backbone of Indigeneity.

World’s Columbian Exposition souvenir coin purse with a painted scene depicting the landing of Christopher Columbus, Chicago, c. 1893. CHM, ICHi-036259

This heritage connects Haiti and the Dominican Republic (DR), which share the island of Hispaniola. The two nations also have a legacy of division based on race and religion that is still playing out today. They developed differently through different patterns of colonization—predominantly Spanish in DR and Spanish (1492–1625) followed by French and then the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) in Haiti.

Haiti’s revolution in 1804 ended the largest revolt by enslaved people in history, and Haiti became the first free Black republic in the Western Hemisphere. Following the Haitian Revolution, colonial powers such as Spain, France, and the United States sought to distance Haiti from Latin America even further, culturally and politically. They feared that Haiti’s example would inspire additional Latin American nations to seek independence. Thomas Jefferson cut off aid to François-Dominique Toussaint L’Ouverture, the leader of the Haitian Revolution. The United States did not recognize Haiti as an independent nation until 1862. The first president of Haiti, Alexandre Sabès Pétion, aided Simón Bolívar in liberating Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia.

There are approximately 40,000 Haitians in the Chicago area, and the Haitian American Museum of Chicago (HAMOC) is an advisor of CHM, as is the Dominican American Midwest Association (DAMA). Haitian migrants continue to migrate to Chicago, as it is a sanctuary city. HAMOC provides legal resources regarding immigration to Haitian and non-Haitian new arrivals and migrants throughout Illinois.

Brazil

Despite Brazil’s colonization by the Portuguese rather than the Spanish, the US Census categorizes Brasileiros as “Hispanic or Latino.” This is another illustration of the entangled identities within Latine as a category.

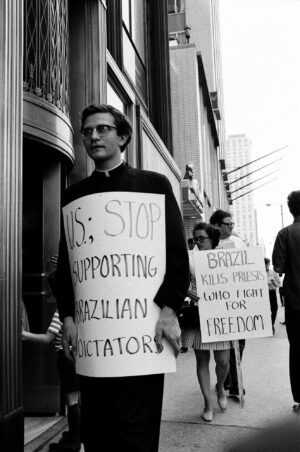

In the 1980s, Brazilians came to Chicago during the dictatorship of João Figueiredo (1964–85), whose regime the United States helped establish. Brazilians in Chicago tend to be middle class and tend to stay in Chicago to work or attend school before returning to Brazil or settling in suburbs.

Members of the Brazilian Consulate protest the murder of Father Antonio Henrique and other Brazilian priests, 903 N. Michigan Ave., Chicago, June 26,1969. ST-60002649-0011, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Brazilian identity is complicated. Many light-skinned Brazilians in Chicago prefer the European identity of “Portuguese” on the census. Afro-Brazilians select “Black not Hispanic,” putting race first. Geopolitically, they also identify as Latin American. There are approximately 55,000 Brazilians in the Chicago area, and the Brazilian Cultural Center is an advisor of CHM.

Philippines

The Philippines is a Southeast Asian nation comprising 7,641 islands with a diverse history of intra-Asian migration and European colonization. During nearly four centuries of colonization in the Philippines, the Spanish profoundly influenced everything from the name of the islands to the form of governance, economy, cuisine, agriculture, religion, social structure, and language. The Hispanic presence in the Philippines also involved trade between Mexico and the Philippines during the 1600s, which resulted in Filipinos living in Mexico and vice versa.

Milk glass dish by Westmoreland Specialty Co. in the shape of an eagle sitting on a nest of eggs, 1898. The ribbon on the front says “The American Hen,” and the eggs are labeled “Purto Rica” (Puerto Rico), Cuba, and Philippines. The design is influenced by the Spanish American War. CHM, ICHi-179109

From the mid-18th century on, Filipinos rebelled against the Spanish, who ruled the Philippines from Mexico until Mexican independence in 1821. By the 1860s, only 5–10% of the population spoke Spanish fluently. The government sought to increase that rate, but Filipinos sought independence. Filipinos nearly had independence in their grasp when the United States stepped in to “assist” in their revolution. Instead, they took over colonial rule from Spain. The United States immediately went to war against the Filipino Revolution (1899–1902/1912) even while working on terms for the Philippines as a new colony.

Portrait of a Filipino string sextet at the WMAQ radio station, Chicago, December 1924. DN-0078368, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

During World War II, the United States and Japan grappled for control of the islands. The Philippines ended up independent but still burdened by their relationship to the United States. According to the Pew Research Center, approximately 145,000 Filipinos live in the Chicago area. The Filipino American Historical Society of Chicago is an advisor on this project.

Belize

Like its neighbors, Mexico and Guatemala, Belize was part of the Maya empire for nearly three millennia, from possibly as early as 1500 BCE to roughly 1200 CE. In the 16th and 17th centuries, the Spanish and British fought over which nation would control Belize as a colony, and Britain won. Belize gained independence from Britain in 1981 but remained part of the Commonwealth. Thus, even though it is geographically part of Latin America, it has some important cultural differences.

In addition, Belize has multiple types of Indigenous cultural heritage, both Maya and Garinagu. The Garinagu people (who speak Garifuna) are descendants of pre-Columbian African traders and Indigenous people of South America. They migrated to the Caribbean island of St. Vincent between 160 and 1220 CE. There, the Spanish, Dutch, French, and British fought for control of the Garinagu land for 300 years until Britain ultimately won. After the Garinagu failed in their rebellion against the British in the 1790s, roughly 5,000 Garinagu were exiled from St. Vincent to Belize, helping to create the mixed population in that country today. Chicago is home to a Garinagu and partly Garifuna speaking population.

Exterior of Garifuna Flava restaurant, 2518 W. 63rd St., which is know for their Caribbean, Latin, and indigenous Garifuna cuisine, July 2024. Image from Google Maps.

There is much more to learn about places that touch on these shared histories. For those interested in more research, the histories of Guyana, Grenada, Guam, Equatorial Guinea, and the Marianas are excellent next steps.

Further Reading

Clémence, Jouët-Pastré, Leticia J. Braga, eds. Becoming Brazuca: Brazilian Immigration to the United States. David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, Harvard: 2008.

Kahn, Jeffrey S. Islands of Sovereignty: Haitian Migration and the Borders of Empire. Chicago Series in Law and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Ocampo, Anthony Christian. The Latinos of Asia: How Filipino Americans Break the Rules of Race. 1st ed. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016.

Page, Joseph A. The Brazilians. Boston: Da Capo Press, 1996.

The Garifuna Journey.Mov, 2021.

Chicago is where the first in a long line of achievements in LGBTQIA+ rights took place. CHM senior public and community engagement manager Gregory Storms writes about the very first LGBTQIA+ rights organization in the United States.

In 1962, Illinois became the first state to decriminalize consensual same-sex sexual relations—41 years before it would be decriminalized nationally. But long before this, Chicago can boast another incredibly important first in queer history: the founding of the Society for Human Rights (SHR). Established a century ago on December 10, 1924, by Henry Gerber (1892–1972), SHR grew out of years of international scientific research and public dialogue about homosexuality.

Portrait of Henry Gerber, c. 1930. CHM, ICHi-024893

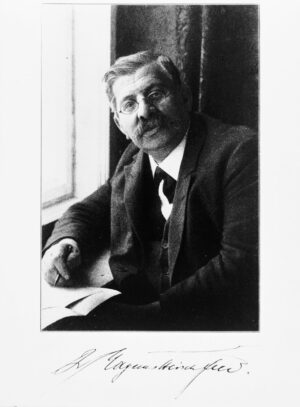

The SHR drew considerable inspiration from foundational German sexologist and advocate for LGBTQIA+ people, Magnus Hirschfeld (1868–1935), who also happened to spend time in Chicago in 1893 during the World’s Columbian Exposition.

Seated portrait of Magnus Hirschfeld, November 12, 1927. US Holocaust Memorial Museum; courtesy of Magnus-Hirschfeld Gesellschaft

During this time, Hirschfeld came upon Chicago’s homosexual subculture, launching his professional trajectory into the field of the science of sexuality. Several years later, back in Berlin, Hirschfeld founded the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (WhK, Scientific-Humanitarian Committee), which advocated for the recognition and legal status of LGBTQIA+ people. Nearly two decades later, Hirschfeld founded the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Science), the world’s first sexology research center, which also advocated for LGBTQIA+ rights on scientific grounds. It would last until 1933 when its library and archives were destroyed in book burning efforts by the Nazi Party.

Gerber was profoundly inspired by Hirschfeld’s work. Having read related publications from the German Homosexual Emancipation Movement of the early twentieth century, Gerber felt that one way to support the deeply oppressed homosexual community was to create and distribute the first known US publication created for other homosexuals called Friendship and Freedom. To receive such a newsletter at this time, however, was a dangerous proposition for many, as it would have been illegal to mail or possess it under the Comstock Act. Therefore, Friendship and Freedom had a very small readership and lasted just two issues.

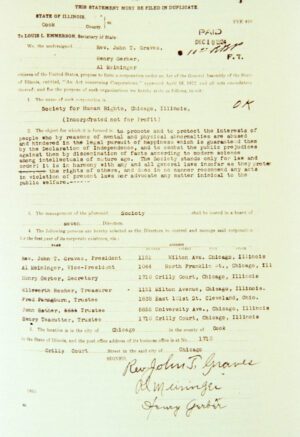

Document establishing the Illinois charter of Society of Human Rights, December 10, 1924. 1987.627 B1, Gregory Sprague papers [manuscript], 1972–1987. CHM, ICHi-039678

Formally recognized with an official State of Illinois Charter on Christmas Eve that year, SHR was sadly short-lived. Limited to only homosexual, cisgender men, SHR prohibited bisexual men from joining the organization.

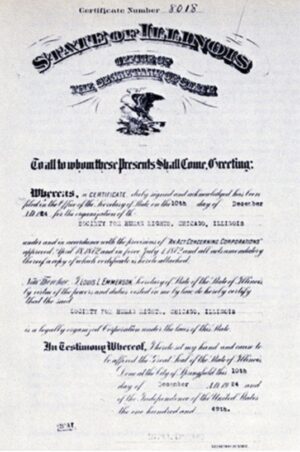

The Society for Human Rights full charter document, granted by the State of Illinois on December 24, 1924. The Legacy Project

However, SHR’s vice president, Al Weininger, was married to a woman, and she eventually tipped off the SHR’s existence, leading to the group’s downfall. Gerber was arrested in 1925 and was reported in the Chicago Examiner in a story titled “Strange Sex Cult Exposed.” Charges against Gerber were later dismissed since he was arrested without a warrant. Still, as was common, Gerber lost his life savings, his job with the Post Office, and he soon left Chicago for New York City where he served in the US Army until being honorably discharged seventeen years later.

The residence at 1710 North Crilly Court is in Chicago’s Old Town neighborhood, about half a mile away from the Museum. National Park Service; courtesy of Shirley and Norman Baugher

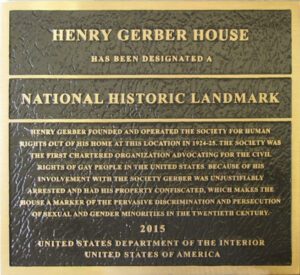

In Chicago, we celebrate the legacy of the SHR and Henry Gerber in several ways. Gerber’s house was named a Chicago Historic Landmark in 2001 and a National Historic Landmark in 2015. The Gerber/Hart Library and Archives, named partly in honor of Gerber, remains Chicago’s primary resource for LGBTQIA+ related collections.

The National Historic Landmark plaque at Gerber’s former residence. National Park Service; photograph by NPS staff

Despite the short life of the Society for Human Rights, it remains a first in US queer history. It would be two decades until we saw similar, more widely recognized LGBTQIA+ right organizations like the Mattachine Society and the Daughters of Bilitis take hold to shape the future of the fight for equality.

Bibliography

Andries, Daniel, Alexandra Silets, and Jane Lynch. Out & Proud in Chicago. Window to the World Communications, Inc, 2008.

Bauer, Heike. The Hirschfeld Archives: Violence, Death, and Modern Queer Culture. Temple University Press, 2017.

Bullough, Vern L. Science in the Bedroom: A History of Sex Research. Basic Books, 1994.

Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame. “Henry Gerber.” Accessed December 3, 2024.

De la Croix, St. Sukie. Chicago Whispers: A History of LGBT Chicago Before Stonewall. University of Wisconsin Press, 2012.

Elledge, Jim. The Boys of Fairy Town: Sodomites, Female Impersonators, Third-Sexers, Pansies, Queers, and Sex Morons in Chicago’s First Century. Chicago Review Press, 2018.

Francis, Meredith. “The Chicagoan Who Founded the Earliest Gay rights Group in America.” WTTW. Accessed December 3, 2024.

Gerber, Henry. “The Society for Human Rights – 1925.” One, September, 1962. Accessed December 3, 2024.

Nash, Carl. “Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement.” Encyclopedia of Chicago. Accessed December 3, 2024.

Johnson, David K. “The Kids of Fairytown: Gay Male Culture on Chicago’s Near North Side in the 1930s.” In Creating a Name for Ourselves: Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Community Histories, edited by Brett Beemyn. Routledge, 1997.

Katz, Jonathan Ned. “Henry Gerber: Gay Pioneer.” In Out and Proud in Chicago: An Overview of the City’s Gay Community, edited by Tracy Baim. Surrey Books, 2008.

Legacy Project. “Henry Gerber – Nominee.” Accessed December 3, 2024.

Legacy Project. “The Society for Human Rights.” Accessed December 3, 2024.

National Park Service. “LGBT Activism: The Henry Gerber House, Chicago, IL.” Accessed December 3, 2024.