Latest Posts

Spend the summer uncovering Latino/a/x stories at the Chicago History Museum

CHICAGO (April 5, 2023) – The Chicago History Museum has openings for 8 Research Associates from June 26 through Aug 18, 2023. Young people from across the city are invited to apply and will contribute to the research for the upcoming exhibition, Aquí en Chicago, opening in fall 2025 at the Chicago History Museum.

Aquí en Chicago, is a response to protests by high school students from Rudy Lozano Academy against CHM for lack of Latino/a/x representation. The exhibition will situate their protest in a long history of 170 years of Latino/a/x resistance to white supremacy and colonialism, as well as presence, and cultural maintenance in Chicago. Aquí is only one part of the museum’s effort to redress a long history of omitting Chicago’s communities of color from its central narrative. The project is also a community-driven initiative that will prepare CHM to share the diverse historical narratives of Latino/a/x people and their integral contributions to the city, setting up the Museum to do more, ongoing work over the long haul beyond the exhibition’s opening.

Positions are open to people ages 16–20 who are not yet attending university. Expected work time is 15 hours per week with payment at $16 an hour for 8 weeks. Applications are due Sunday, April 23. The application is open and available in English and Spanish.

Media Kit: https://app.box.com/s/nc9hj30kgengwq7zl90p1yb2c66jvt98

###

CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman talks about the significance of Passover and shares a brief history of Chicago’s Jewish communities.

Sundown on Wednesday, April 5, 2023, marks the beginning of the Jewish holiday of Pesach or Passover. Celebrated by the Jewish diaspora for eight days, it is a time to remember the biblical story of Moses leading the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt. Also known as the Feast of Unleavened Bread, Passover is remembered through removing all chametz (yeast) from one’s home and not eating anything yeast-leavened for the days of remembrance as a form of sacrifice and a representation of removing sin from one’s life.

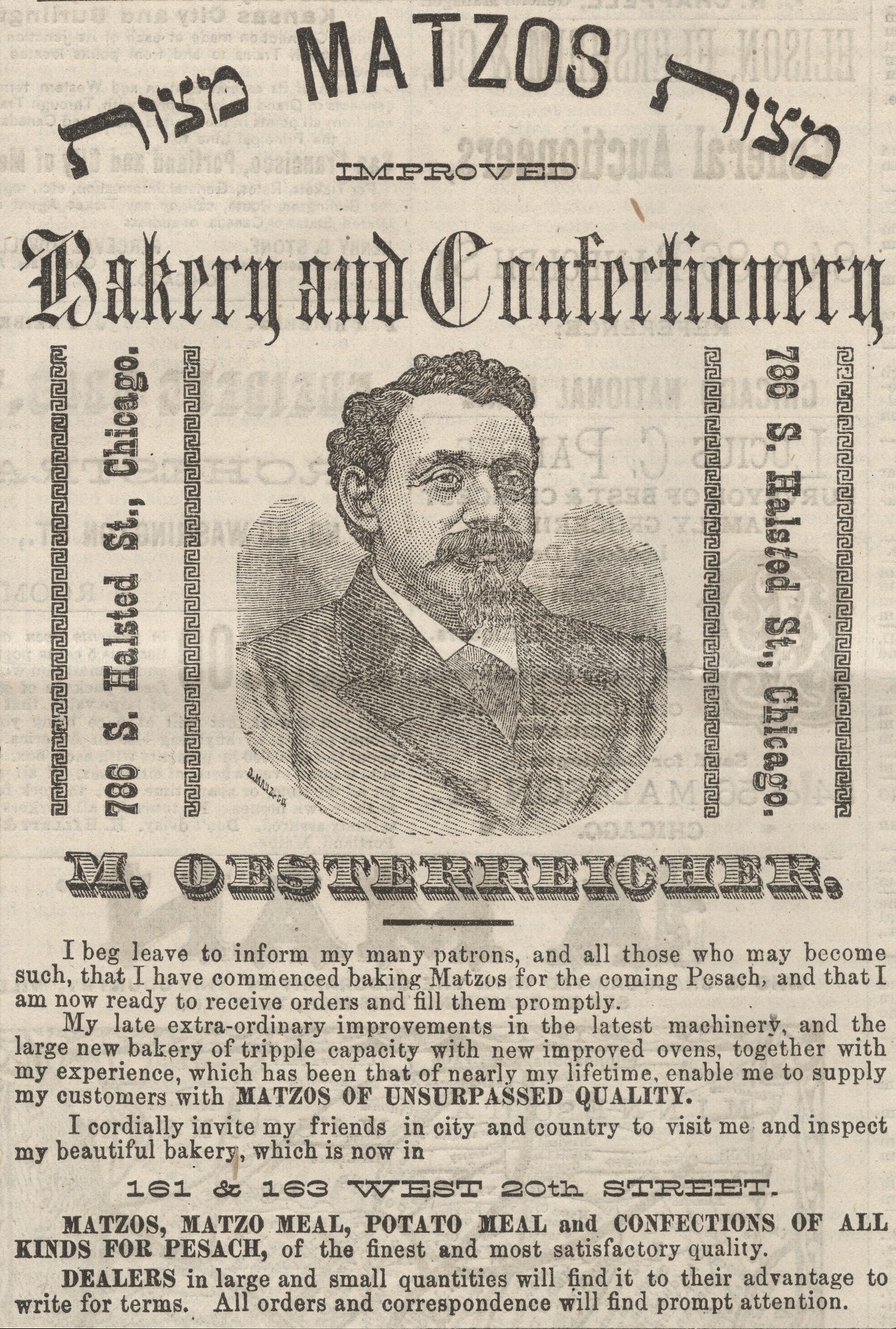

Left: Advertisement for M. Oesterreicher Bakery and Confectionery at 786 S. Halsted St. from The Occident Newspaper, 1885. CHM, ICHi-067038. Right: Advertisement for the Wittenberg Matzoh Co. at 1326 S. Jefferson St., from The Sentinel Newspaper, March 18, 1937.

Another important part of the tradition is the Passover seder meal. Jewish families gather and ritually retell the story of the Exodus from Egypt through eating symbolic foods and drinks and reading from a text known as the Haggadah.

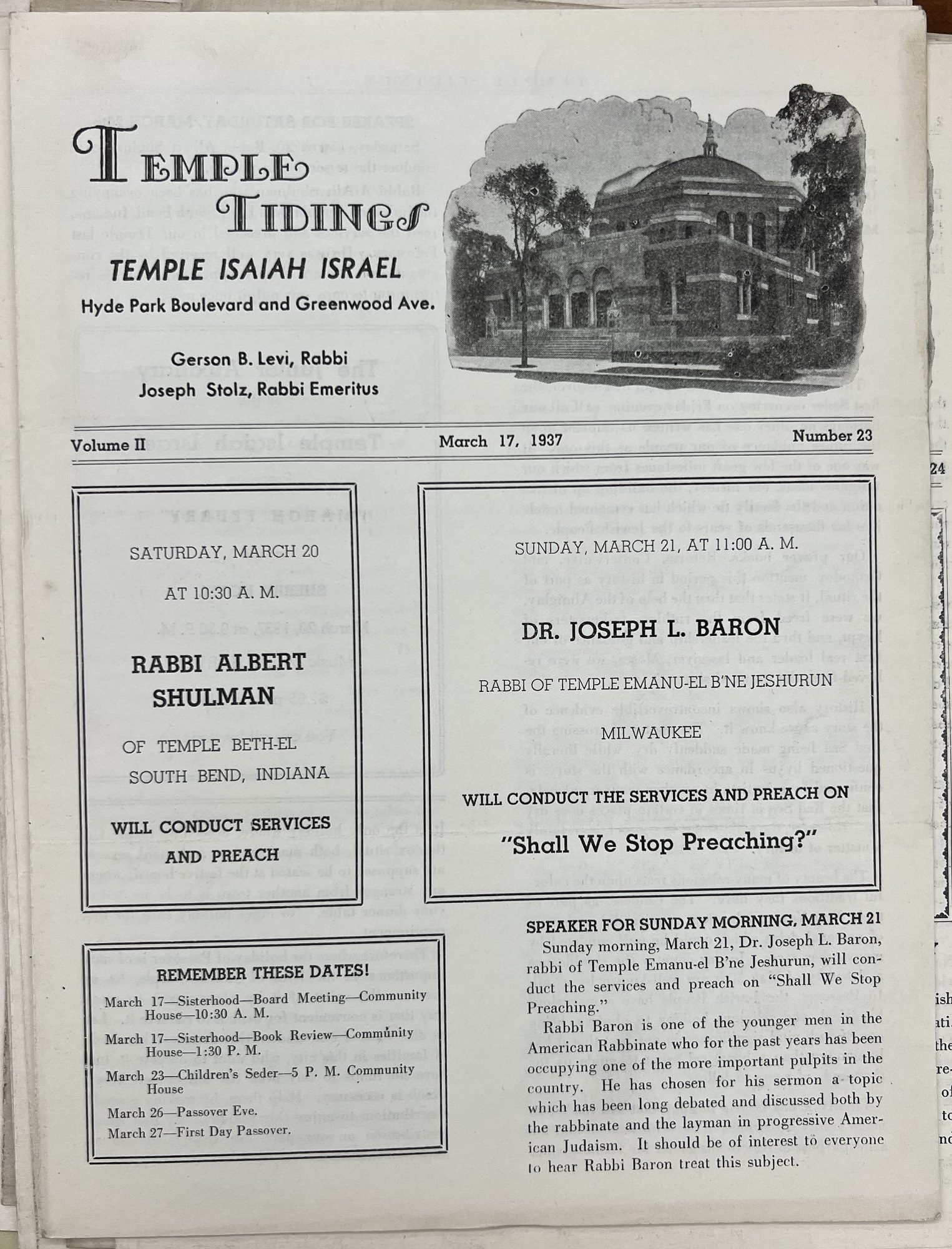

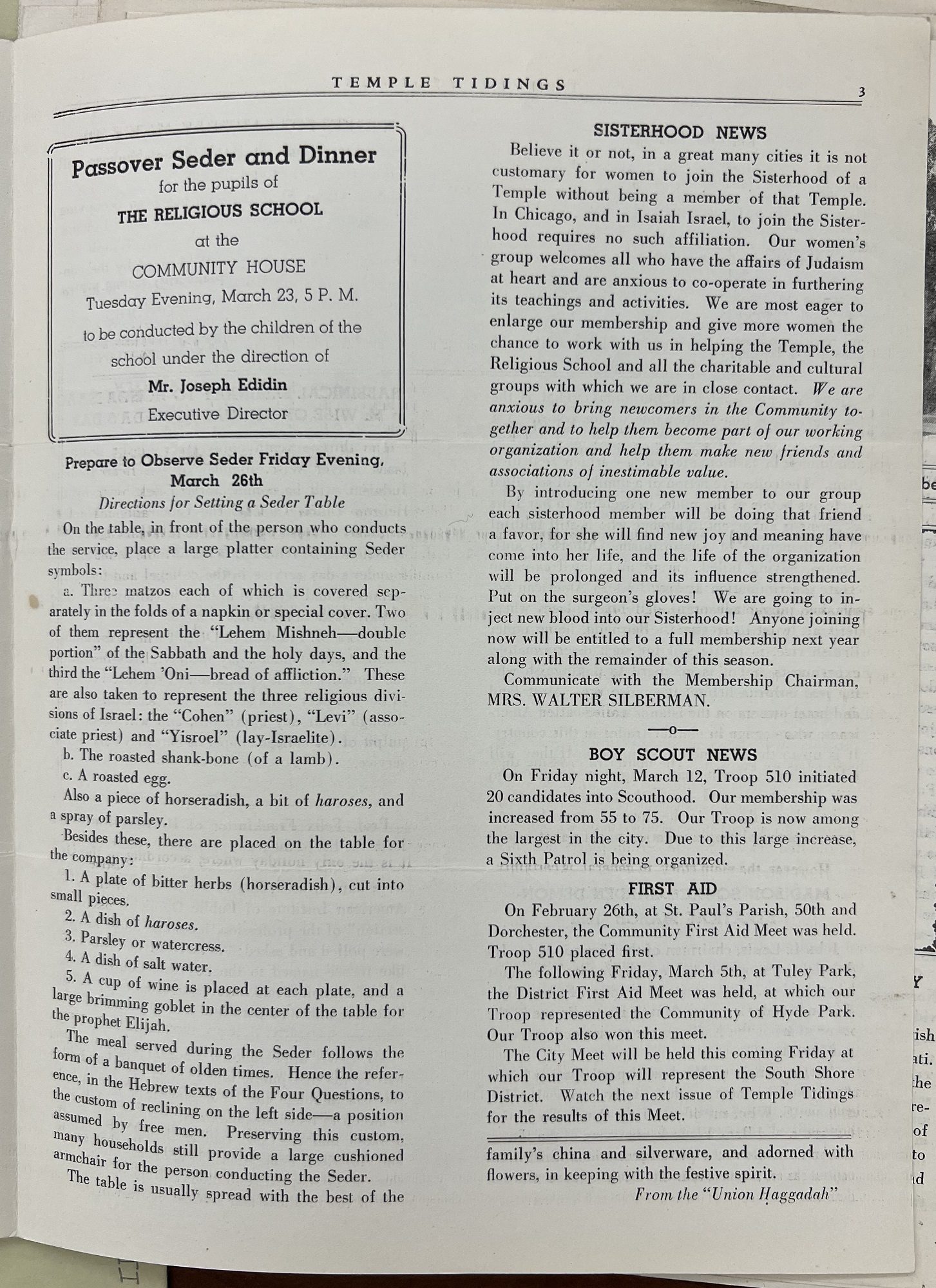

Two editions of Temple Isaiah Israel’s Temple Tidings, March 1937. From MSS Lot K.A.M. Isaiah Israel, CHM collection.

These 1937 congregational bulletins from Temple Isaiah Israel share the meaning of Passover and the Seder meal as part of their Passover editions of Temple Tidings. Inside the March 17 edition is a description of the elements needed for a seder and instructions for community members on the proper ways to prepare the table in remembrance. One of the central foods of Passover is matzah (plural matzos), a specific type of flat bread made of just flour and water, that is eaten in place of yeasted bread at every meal.

March 17, 1937, edition of Temple Isaiah Israel’s Temple Tidings. From MSS Lot K.A.M. Isaiah Israel, CHM collection.

As the bulletin describes, three matzos are included at the seder meal on a large platter, known as a seder plate, along with a shank bone, a roasted egg, horseradish, haroses (a mixture of fruits, nuts, and spices), parsley, and salt water. Each of these foods is eaten at specified times as the Haggadah is read, and they are accompanied by drinking four symbolic glasses of wine.

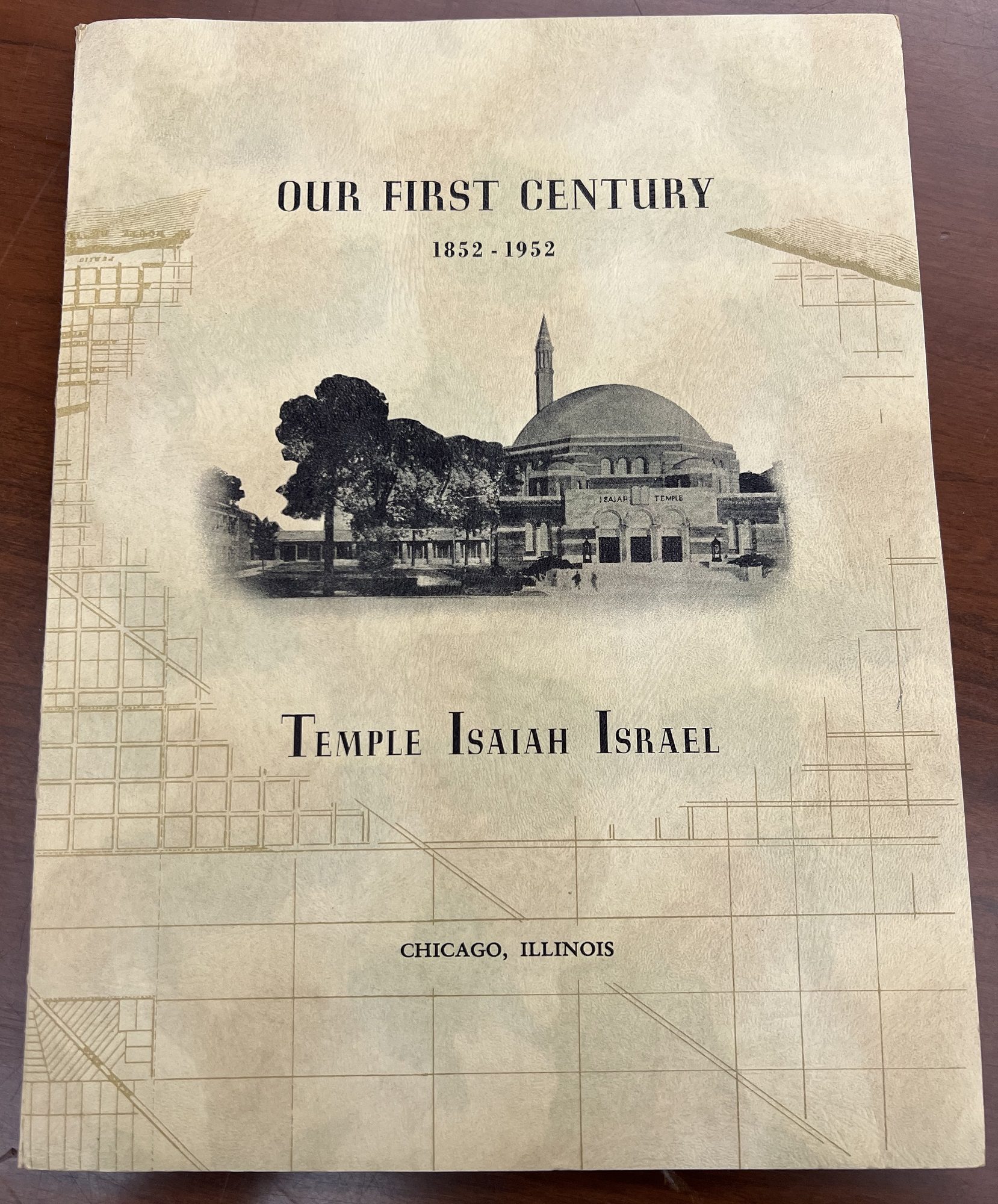

Commemorative book written by Rabbi M. M. Berman at the centennial celebration of Temple Isaiah Israel (B’nai Sholom), 1952. CHM Research Collection, F38W .Y-I7 1952 OVERSIZE

Temple Isaiah Israel’s congregational history demonstrates some of the many shifts, changes, mergers, and migrations that have defined Chicago’s Jewish communities. Jewish migration to Chicago began in the 1830s, with the first permanent Jewish families settling in 1841. The earliest synagogue in Chicago, Kehilath Anshe Maariv (Congregation of the Men of the West) (KAM), was founded in 1847 and led by German Jews who leaned Reform in their form of religious practice.

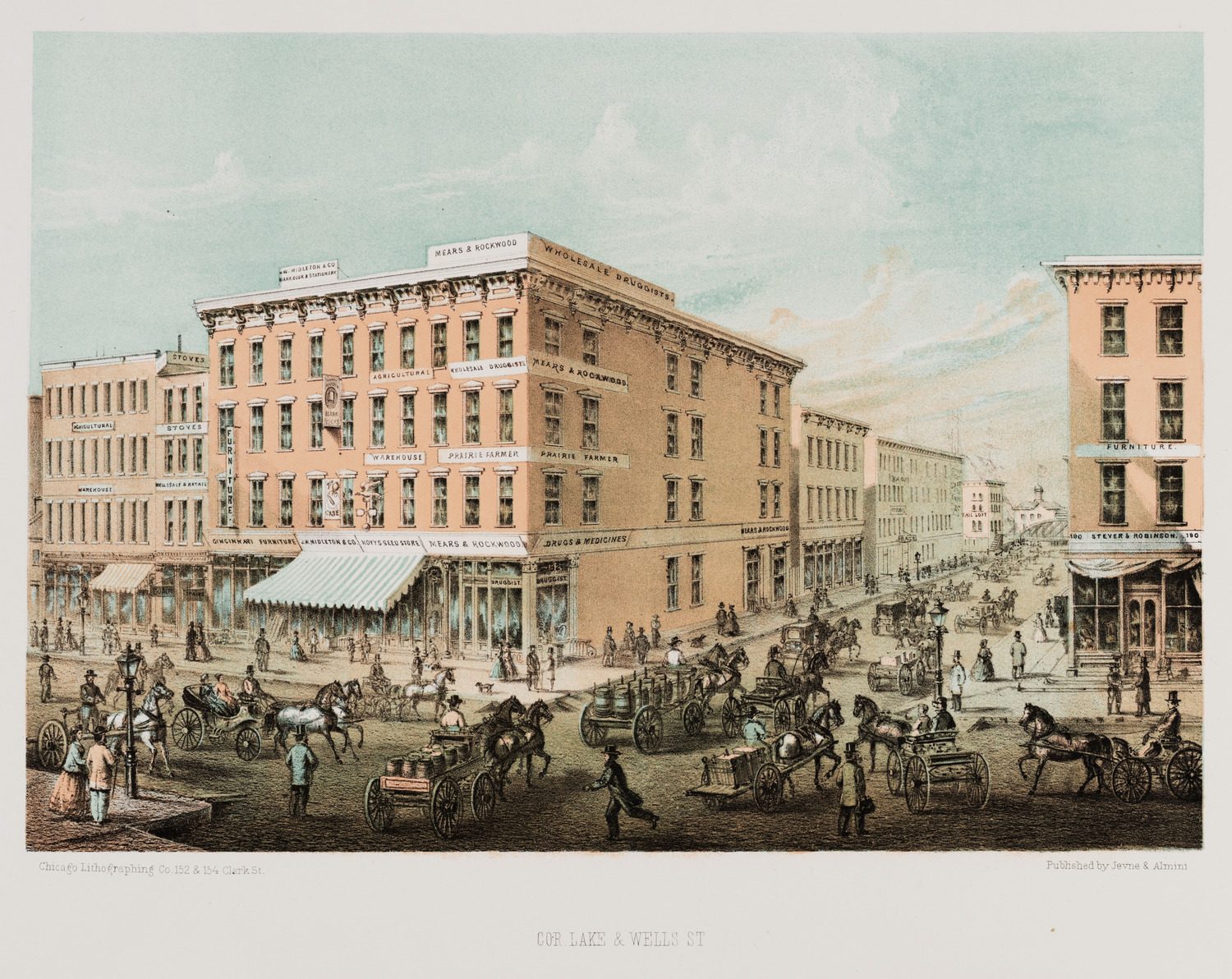

Intersection of Lake and Wells Streets, near the first meeting place for B’nai Sholom, c. 1867; lithograph by Jevne and Almini. CHM, ICHi-040005

Just five years later, Chicago’s second-oldest congregation was organized by former KAM community members who identified as Polish Jews and leaned more Orthodox in practice. Calling themselves Kehilath B’nai Sholom (Congregation of the Children of Peace), they first met above a clothing store at 189 Lake Street, followed by a couple other temporary locations, before laying the cornerstone of their first building at Harrison Street and Fourth Avenue in 1864.

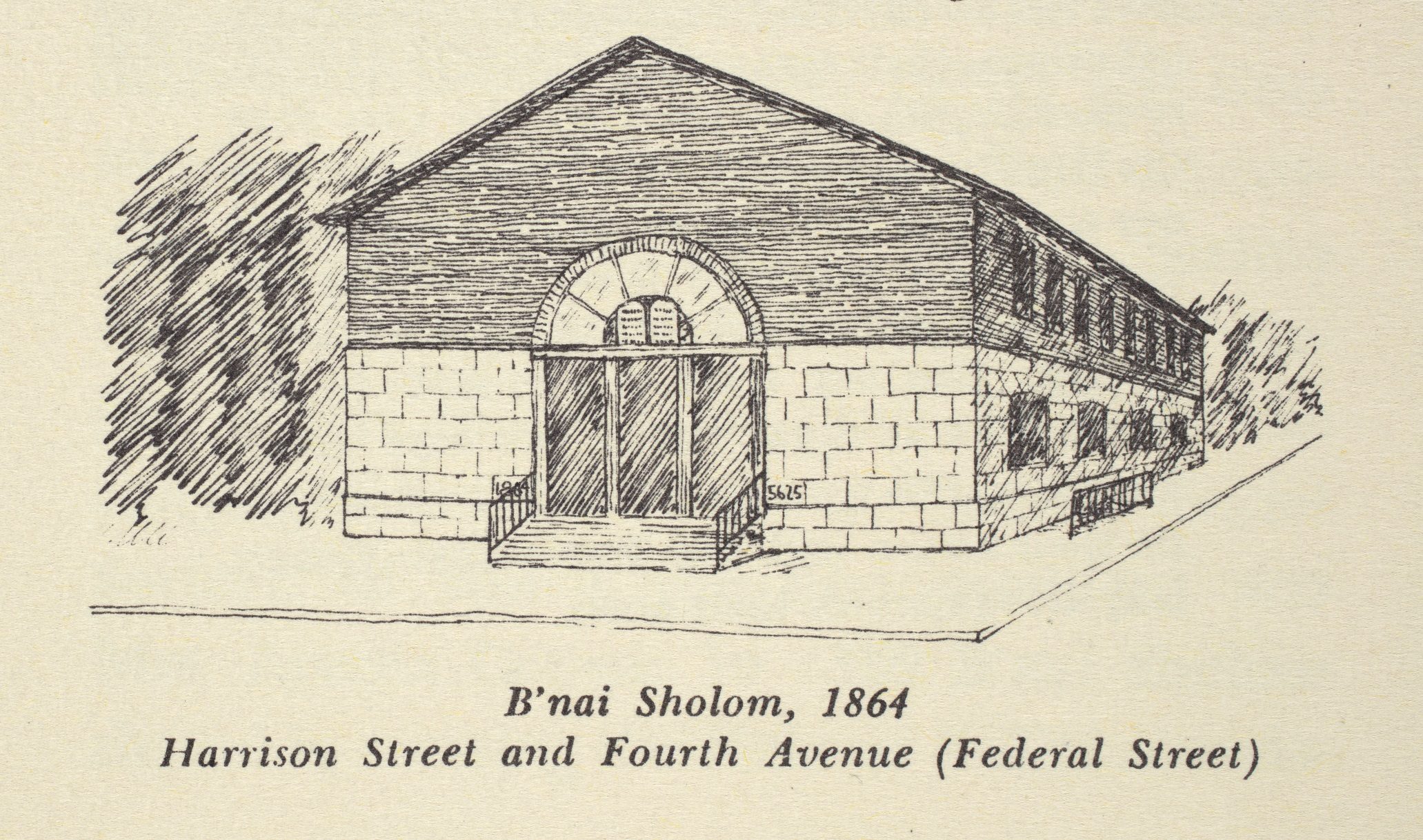

Architectural drawing of the exterior of B’nai Sholom, 1864. From Our First Century, 1852–1952: Temple Isaiah Israel, the United Congregations of B’nai Sholom, Temple Israel and Isaiah Temple, p. 14. CHM, ICHi-173824A

After losing this building to the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, B’nai Sholom briefly rented a church to hold worship before building a new synagogue on Michigan Avenue between Fourteenth and Fifteenth Streets. Before long, they outgrew this building and moved in 1886 to one formerly owned by KAM.

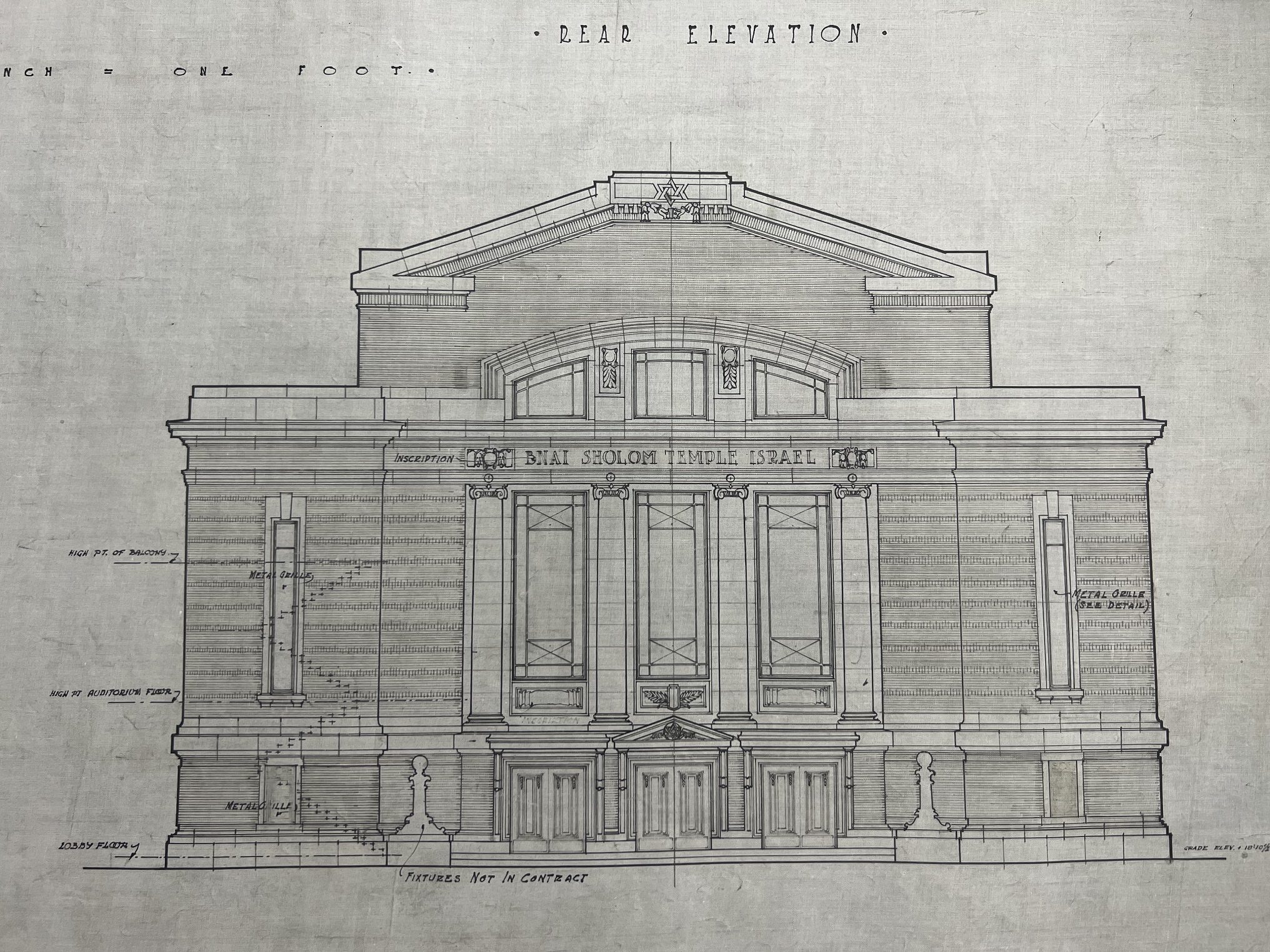

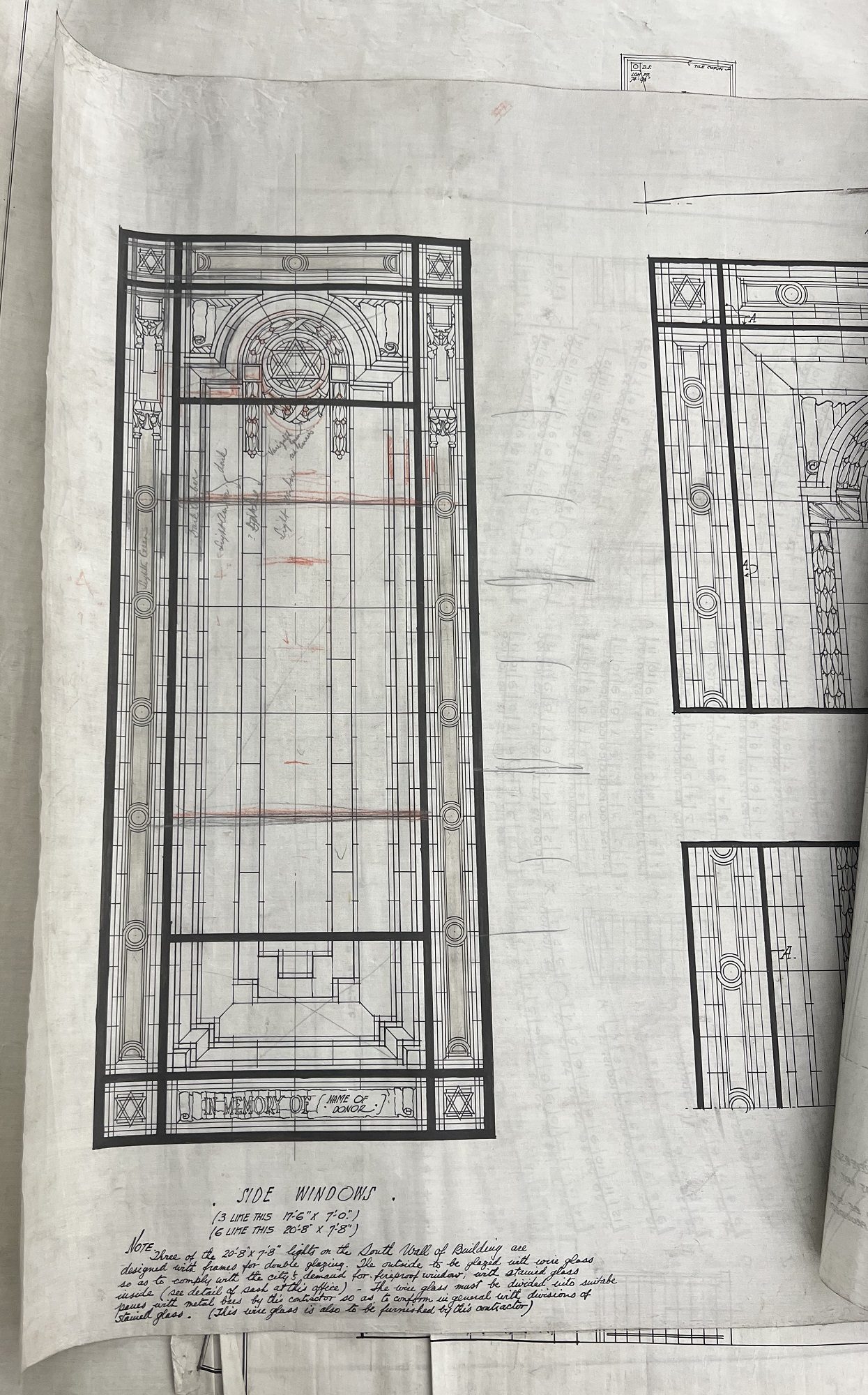

Architectural drawing details for B’nai Sholom Temple Israel by Alfred S. Alschuler, April 1, 1913. CHM collection. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

Architectural drawing details for B’nai Sholom Temple Israel by Alfred S. Alschuler, April 1, 1913. CHM collection. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

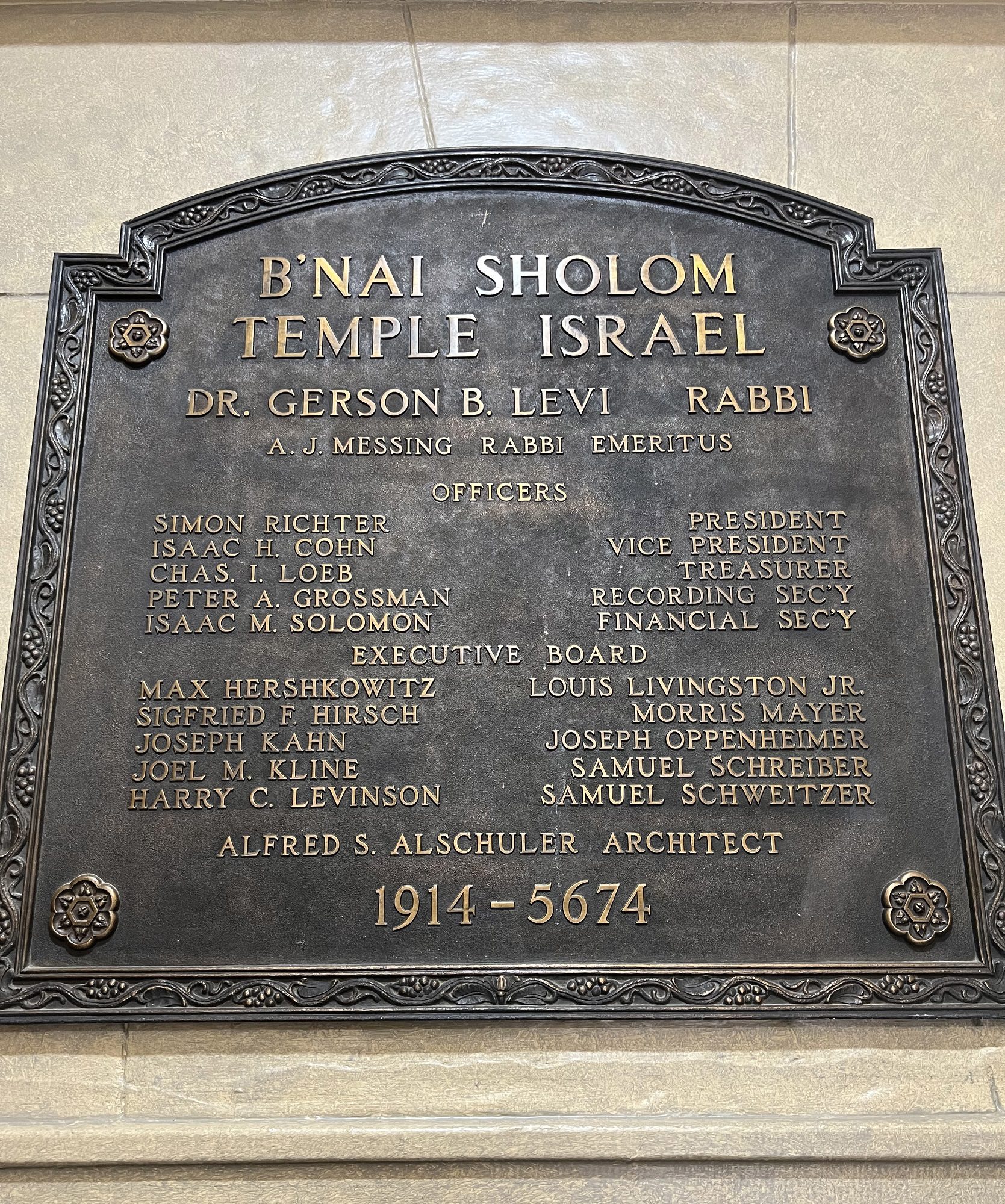

As the wider Jewish community grew, more offshoot congregations were created. Temple Israel (known as the “People’s Synagogue”), branched off from KAM in 1896. A decade later, B’nai Sholom and Temple Israel merged to become B’nai Sholom Temple Israel, originally meeting in Temple Israel’s building at Forty-Fourth and St. Lawrence Streets and later building a new purpose-built synagogue designed by Alfred Alschuler in 1914.

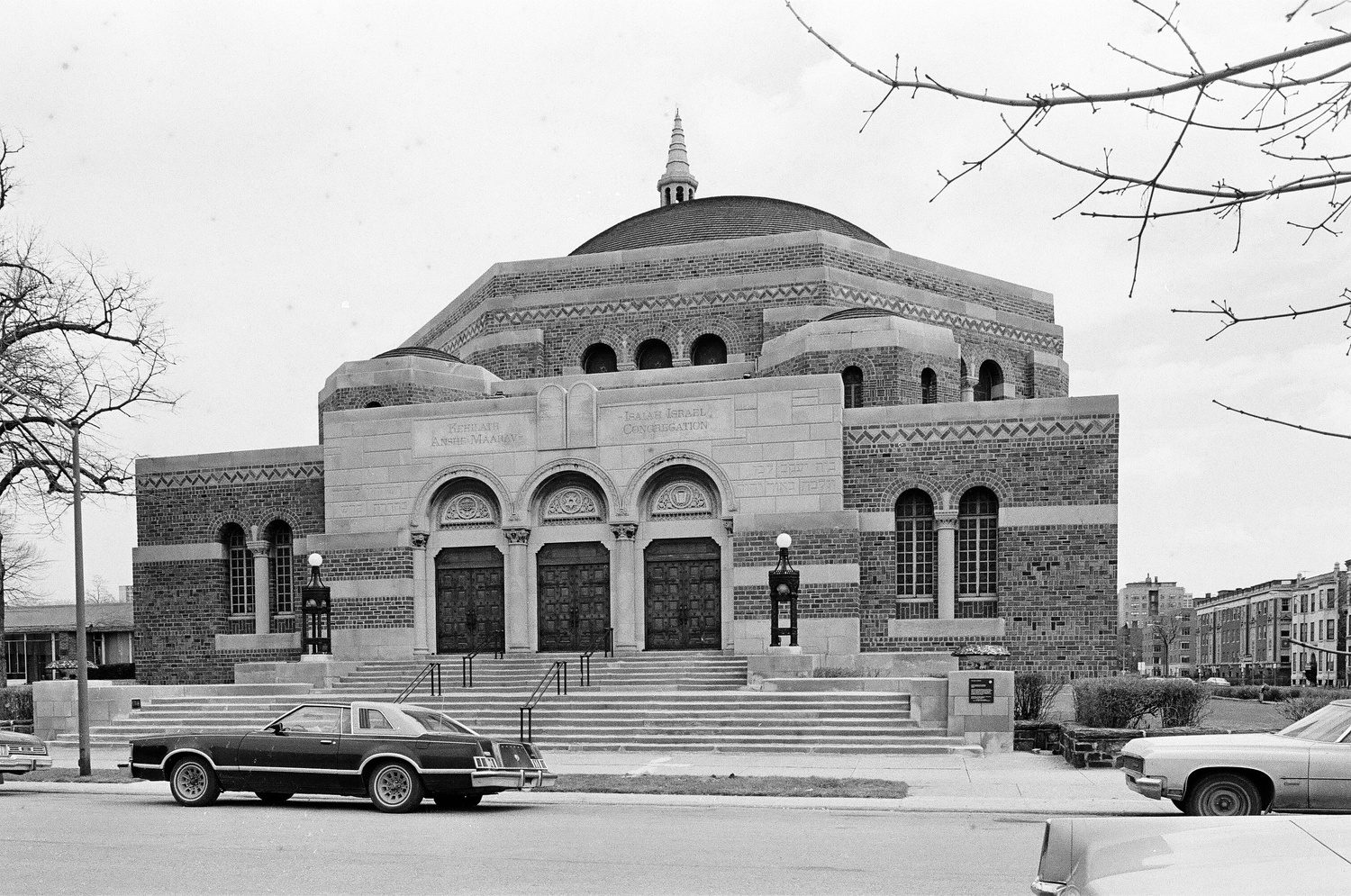

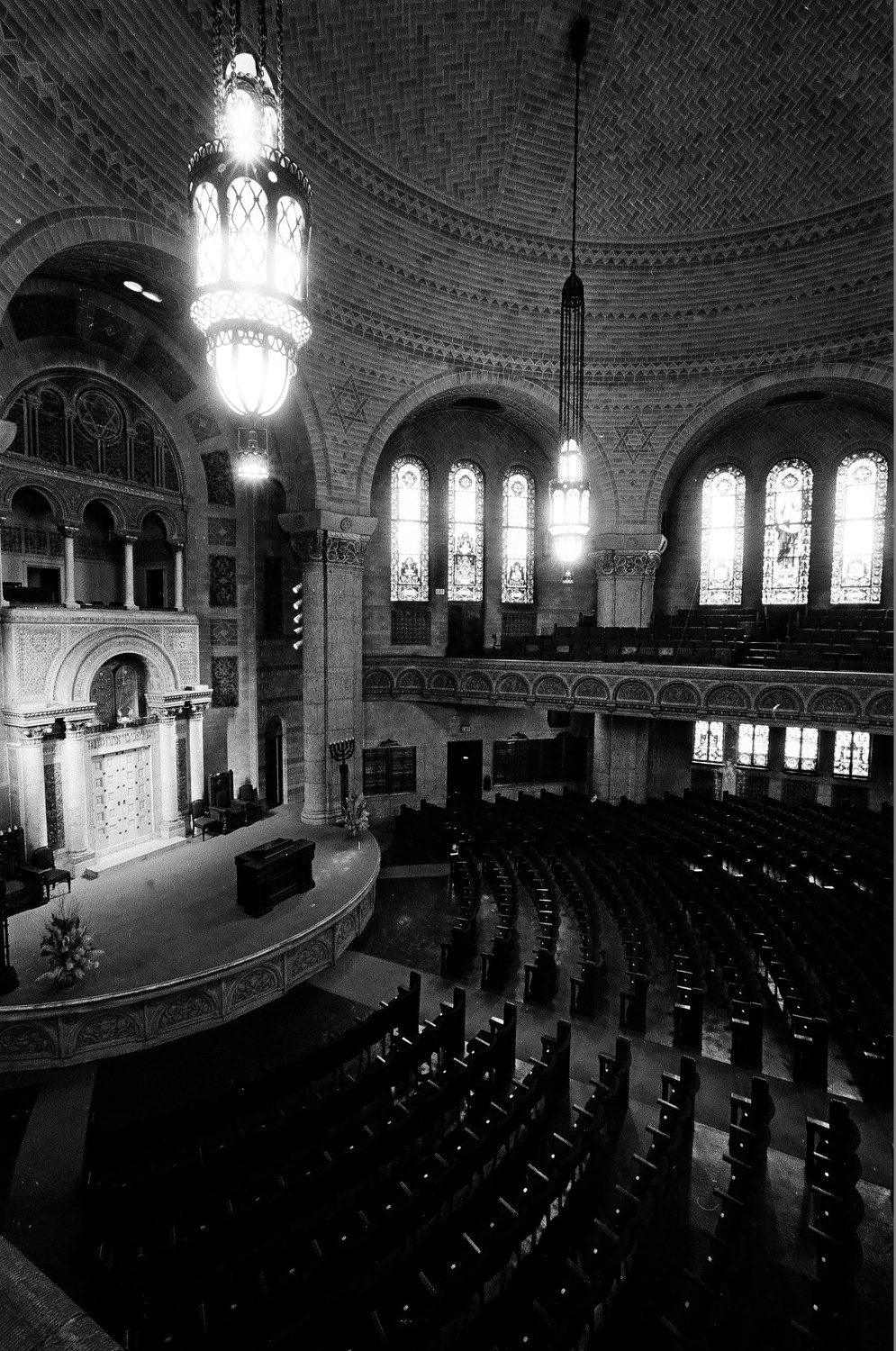

Exterior (top) and interior (below) of Temple KAM Isaiah Israel, 1979. ST-80004699-0024 and ST-80004699-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

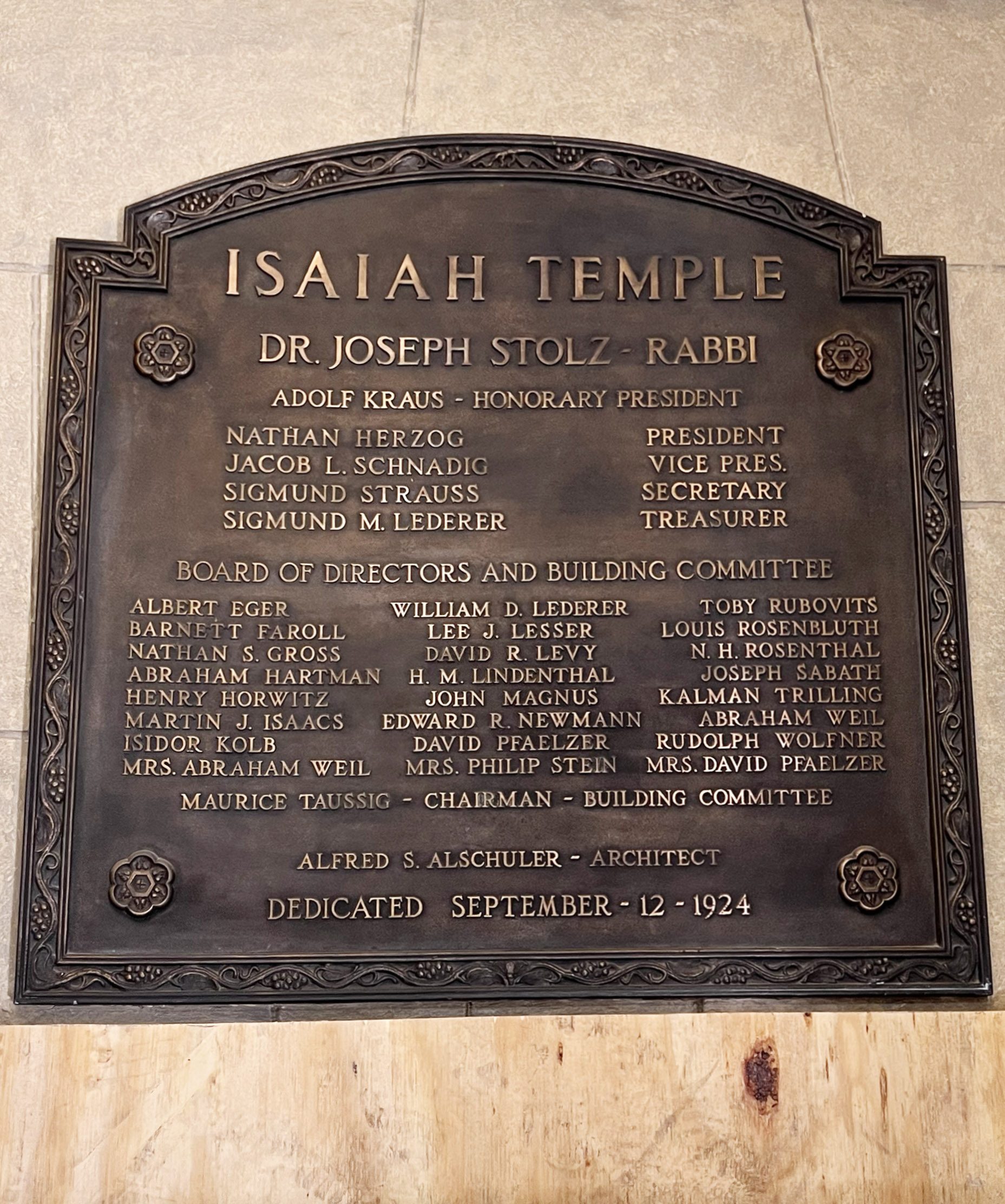

In 1924, further migration and mergers took place with Isaiah Temple, another outgrowth congregation that had formed in 1895. Together, the three congregations became known as Temple Isaiah Israel. The congregation built a stunning neo-byzantine synagogue in the Kenwood neighborhood, also designed by Alschuler.

Memorial plaques inside KAMII from its joining congregations, 2022. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman

In 1971, the congregational mergers came full circle as KAM joined Temple Isaiah Israel to also make Hyde Park Boulevard their home. Today, KAM Isaiah Israel (KAMII) is still an active, thriving congregation celebrating 175 years of presence in Chicago.

KAMII, exterior (top) and interior (below), 2022. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman

Additional Resources

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Chicago’s Jewish community

- See more of architect Alfred Alschuler’s work

- Read the Chicago History magazine article “Welcoming Jewish Americans” on the history of Chicago Hebrew Institute

To kick off March Madness and Women’s History Month, CHM content manager & editor Heidi Samuelson writes about Dorothy Gaters, a history-making basketball coach.

Coach Dorothy Gaters, c. 1992. STM-030472572/Chicago Sun-Times

The 2023 Illinois High School Association (IHSA) girls’ basketball 4A, 3A, 2A, and 1A state final tournaments are being held March 2-4 in CEFCU Arena in Normal, Illinois. You can’t talk about the history of high school basketball in Illinois without including legendary coach Dorothy Gaters.

Gaters coaching John Marshall High School in a loss to George Washington High School in the Girls’ Basketball Public League Championships at the International Amphitheatre, 4220 South Halsted Street, Chicago, February 18, 1991. ST-40002324-0032, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The winningest high school basketball coach in Illinois history, for more than 45 years, Gaters coached at John Marshall Metropolitan High School in the East Garfield Park community area on the city’s West Side. In 1972, Title IX became federal law as part of the Education Amendments of 1972, prohibiting sex discrimination in educational institutions that receive federal funding. Although girls’ high school basketball teams existed in Illinois since 1895, it was only after Title IX that the IHSA allowed girls to participate in interscholastic basketball contests starting in 1973, with the first state tournament in 1976.

Gaters coaching John Marshall High School in a loss to George Washington High School in the Girls’ Basketball Public League Championships at the International Amphitheatre, 4220 South Halsted Street, Chicago, February 18, 1991. ST-40002324-0032, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

There was no girls’ basketball team at Marshall when Gaters was a student there, graduating in 1964. It was shortly before completing her degree in physical education from DePaul University that she formed an Amateur Athletic Union team called the Debs, which played for a few years in the city—the extent of her own playing career.

West Head Coach Dorothy Gaters of Chicago talks with her team before the start of the Girls McDonald’s All American Game at the United Center, March 30, 2011. STM-020503925, Scott M. Bort/Chicago Sun-Times

Gaters took the job at Marshall in 1975, building the program when very few Black women were coaching in public school leagues. As head coach, Gaters earned a record-setting 1,153 wins, with 217 losses. She led Marshall to state championship victories 10 times, in 1982, 1985, 1989, 1990, 1992, 1993, 1999, 2008, 2018, and 2019, and 24 city championships. She coached 17 high school All-Americans and five former WNBA players, including Cappie Pondexter, two-time WNBA champion with the Phoenix Mercury.

Marshall’s coach Dorothy Gaters talks to her players during a game on January 14, 2020. STM-89026892, Kristen Stickney/Chicago Sun-Times

In addition to coaching at Marshall, Gaters served as an assistant coach at the US Olympic Festival in 1986, helping the South win a gold medal, and the WBCA Girls’ High School All-America Game in 1992. She was inducted into the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in 2000 and the NFHS National High School Hall of Fame in 2018. Though no longer coaching, Gaters still works as the athletic director at Marshall High.

Marshall coach Dorothy Gaters accepts a trophy during a ceremony honoring her 45-year career, c. 2020. STM-103811426, Kristen Stickney/Chicago Sun-Times

Additional Resources

- Listen to a 2016 oral history interview with Dorothy Gaters that was part of CHM’s collaborative, youth-conducted oral history project with Breakthrough Urban Ministries, a community-based organization that provides social services on Chicago’s West Side

- Watch the film Forty Blocks – The East Garfield Park Oral History Project, which was made by Breakthrough youth with their filmmaking mentors and includes Gaters’s interview

- See more images in our Chicago Sun-Times collection of area high school basketball championships

When the lights turn off at the end of the day, do the artifacts come out and play? Some Chicago History Museum staff members think so. In fact, 13 of the creepiest dolls in the Museum’s collection have gotten loose, and we need help finding them! Haunted Dolls and History Horrors marks the start of “spooky season” at the Chicago History Museum. This limited time exhibition and scavenger hunt is intended for adults and children alike and features dolls with their own interesting tale and ties to some of Chicago’s dark history. Haunted Dolls and History Horrors will run from Tuesday, September 27, through Sunday, November 6, 2022.

“I am excited for people to view items from our collection that aren’t normally shown, and learn about some frightening and intriguing tales from Chicago’s history in an interactive way” said Charles Bethea, Andrew W. Mellon Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Chicago History Museum.

Those that dare, can stop by the Ticket Desk on the 1st floor to get a Haunted Dolls scavenger hunt guide. There are two guides available: one for adults and one for children in both English and Spanish. As you explore Chicago: Crossroads of America, keep your eyes peeled. The dolls are hiding in 13 spots, including one on the 1st floor. Be on the lookout, but beware of their haunting stares. Each doll has shed its once playful nature and adopted an eerie persona, representing—or misrepresenting—some of the most unnerving, frightening tales from Chicago history. Those who are brave enough to find them all can tell our staff at the Ticket Desk and win a special prize—quick, before they change your history!

For more information, visit chicagohistory.org/dolls. For access to images and logos please see the press kit.

WHAT:

This International Transgender Day of Visibility, please join the OUT at CHM committee at the Chicago History Museum to learn about the community work of LGBTQIA+ organizations who have fought for transgender equality for years, laying a foundation for LGBTQIA+ youth in Illinois to grow up with greater levels of support than ever before.

Over the past several years, the United States has witnessed an unprecedented increase in proposed laws that would limit the rights of members of the transgender and nonbinary communities, with the Human Rights Campaign calling 2021 the “most anti-transgender state legislative season in history.” Many bills have specifically targeted transgender youth, aimed at preventing them from engaging in sports and accessing gender-affirming health care. Illinois, however, has often been at the forefront of LGBTQIA+ rights, stemming all the way back to 1924 with the founding of the Society for Human Rights, the nation’s first known gay organization.

Event Panelists:

- Gearah Goldstein, GenderCool

- Bonsai Bermúdez (they/them/theirs), cofounder and executive artistic director of Youth Empowerment Performance Project

- K. Tajhi Claybren, Integrative Empowerment Group, PLLC

- Avi Bowie (he/him/his), clinical social work/therapist, MA, LCSW

WHERE:

Chicago History Museum, 1601 N Clark St, Chicago, IL 60614

WHEN:

Friday, March 31, 2023, 6–9:00 p.m.

Cost: $20; $15 members

Learn More: http://chicagohistory.org/out

KEY ASSETS AVAILABLE:

- Social media toolkit and logos: https://app.box.com/s/vcfmlfkeh960k3gumf3qah0blc7ey4bt

MEDIA CONTACT:

Veronica Casados

Public Communications Manager

312.799.2161

The Vietnam War Veterans Recognition Act was signed into law in 2017, making each March 29 a day to honor and commemorate Vietnam War veterans. More than 9 million American personnel served on active duty from 1964 to 1975.

Exterior view of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Chicago, November 19, 1999. CHM, ICHi-039078

One Chicago institution with deep ties to the ongoing legacy of the Vietnam War is Our Lady of Guadalupe Church in South Chicago at 91st Street and Brandon Avenue.

Our Lady of Guadalupe began serving the predominantly Mexican families on Chicago’s Southeast Side in 1923, holding services in a former military barrack. The Mexican community developed around the city’s shipyards and steel mills, where they found steady and nearby jobs as they settled in the area. In fact, the church was an important sign that a population of once-migrant workers had coalesced into a community. In 1924, the Claretian Missionaries took over Our Lady of Guadalupe and constructed the current church edifice, a project to which parishioners in the community contributed significantly. The completion of the church marked it with the distinction of being the first house of worship in the city to offer services for Spanish-speaking people, though their early masses were in Latin. Under Claretian leadership, the church would also become home to the National Shrine of St. Jude, patron saint of hope and impossible causes.

Exterior view of the entrance to Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, Chicago, November 19, 1999. CHM, ICHi-039829

By the 1960s, at the height of the Vietnam War, South Chicago was a bustling community with Our Lady of Guadalupe at the heart of social life. Many in the community felt a call to action to serve in the armed forces as the conflict abroad continued to grow, even as antiwar protests continued to mount across the nation. For many of the Mexican men from the neighborhood who enlisted or had their number called in the draft, military service was already a part of the family history, as several older community members were veterans of World War II and the Korean War. This patriotism would come at a high cost, not just for these men’s families, but for the South Chicago community as a whole.

Vietnam veterans’ memorial at Our Lady of Guadalupe Church, Chicago, November 19, 1999. CHM, ICHi-039828

Our Lady of Guadalupe is believed to be the parish with the largest loss of life in the war not just in the city, but across the entire United States. The parish community lost twelve men: Edward Cervantez, Antonio G. Chavez, Leopoldo A. Lopez Jr., Joseph A. Lozano, Michael S. Miranda, Raymond Ordoñez, Thomas R. Padilla, Joseph A. Quiroz, Dennis J. Rodriguez, Peter Rodriguez, and brothers Alfred Urdiales Jr. and Charles Urdiales Jr. Many who did return home from the war were also irreparably changed, suffering from PTSD and the shame associated with being a part of a highly unpopular militarized effort.

The mural as seen on Google Maps, October 2022.

For many, Our Lady of Guadalupe has become a place of memory and a place of healing. The men who lost their lives are forever enshrined in a memorial across the street from the church, dedicated in 1970, which includes a red stone depicting the names of the fallen. A mural honoring the soldiers was completed in 1990. Every year, the church becomes a pilgrimage site during Veterans Day and Memorial Day, when hundreds of visitors come to pay respect to those who paid the ultimate sacrifice in the name of serving their country. In 2002, an honorary Chicago street sign was installed at 91st Street and Brandon Avenue, naming it “Fallen Soldiers Corner.”

Additional Resources

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s interviews with many of the key figures who shaped the debate about the Vietnam War.

- View images in our collection related to the Vietnam War.

CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman talks about the significance of Ramadan and shares a brief history of Chicago’s Muslim communities.

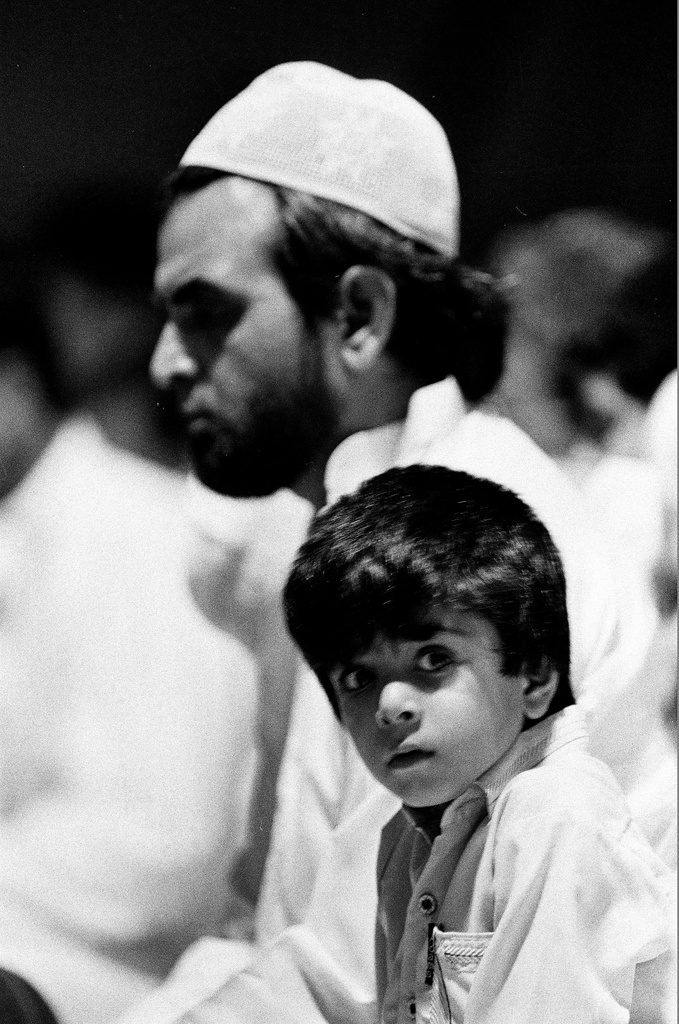

Sundown on March 23 marks the beginning of the Islamic month of Ramadan, a time of prayer, fasting, and personal and community reflection. Ramadan is the ninth month of the Hijri (the Islamic lunar calendar) and considered the holiest month of the year. It commemorates the revelation of the Quran to the Prophet Muhammad. Sawm (fasting) is one of the five pillars of Islam. During Ramadan, people fast from sunrise to sunset for 30 days, breaking the fast daily with the evening iftar meal. The month closes with Eid al-Fitr, a daylong celebration that includes saying special prayers, charitable giving of time and money, spending time with family, and eating delicious food, especially sweets like dates, cookies, donuts, and pies.

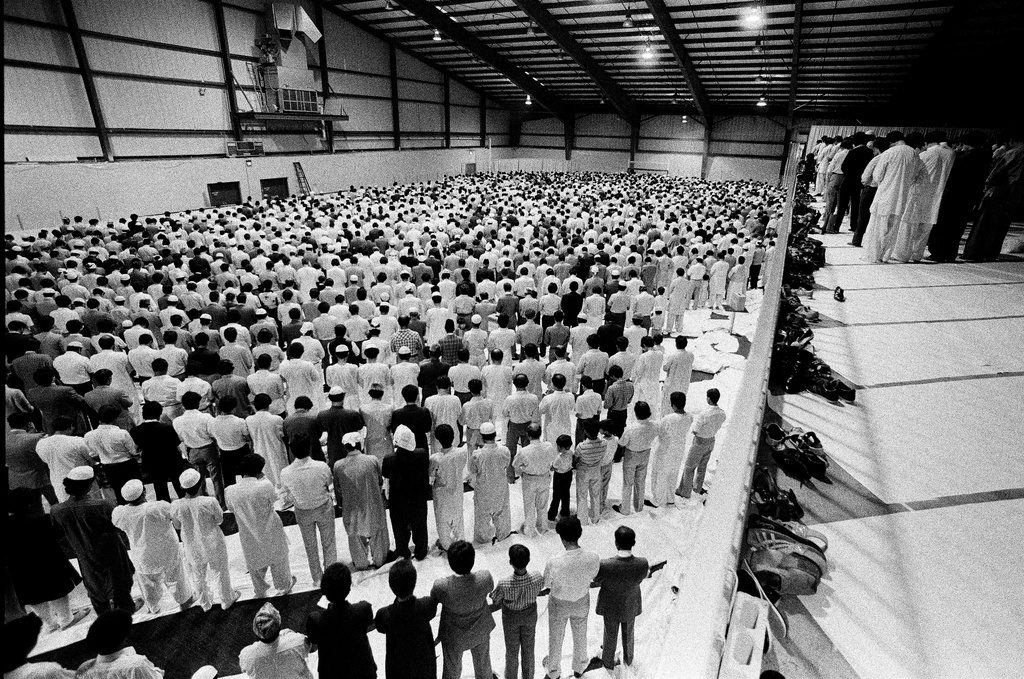

Eid al-Fitr celebration marking the end of Ramadan at the Odeum Expo Center in Villa Park, Illinois, 1983. ST-19041602-0011, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

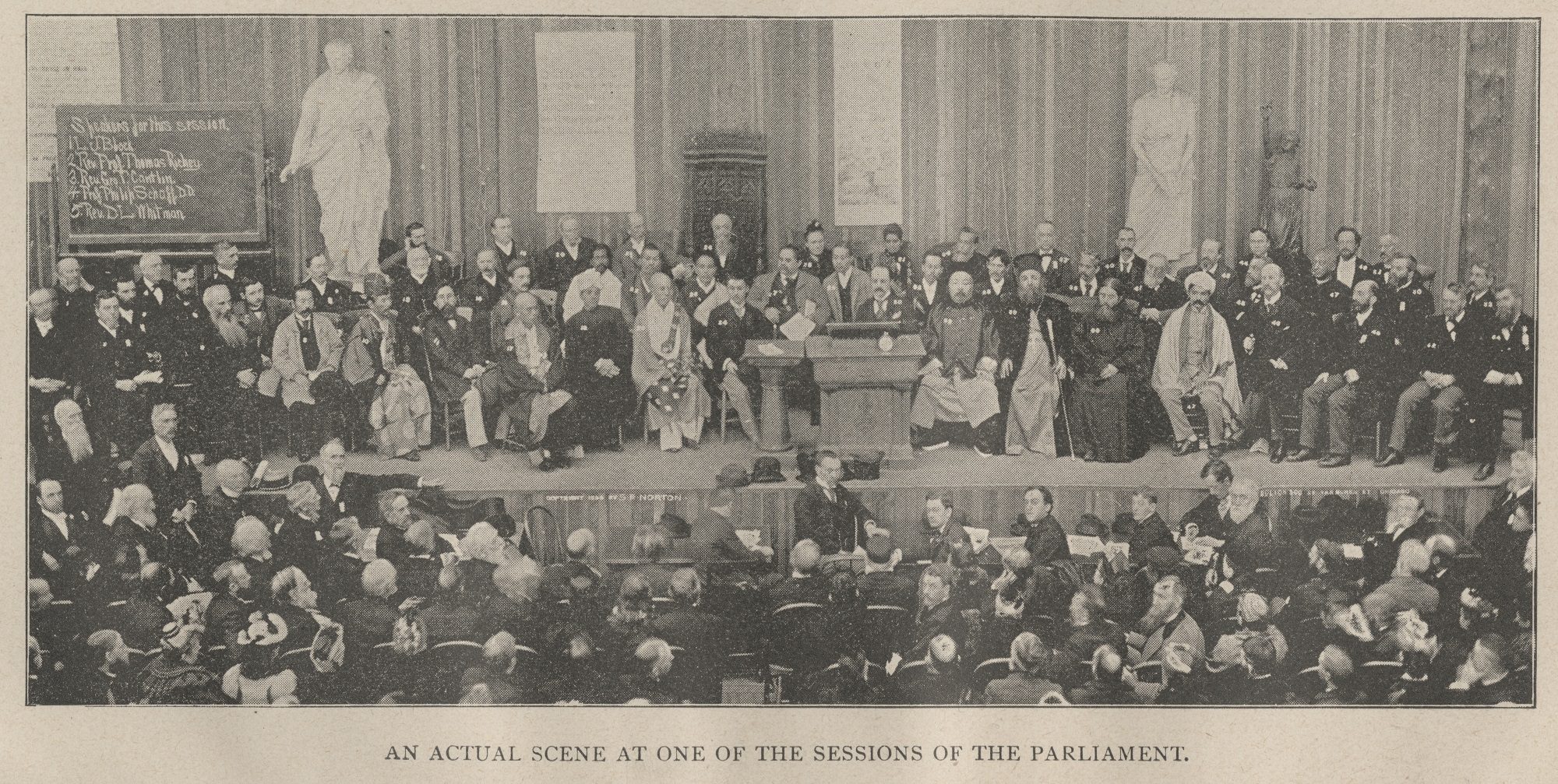

The Muslim community in Chicago and its metropolitan area is richly diverse thanks to 130 years of migration. The first documented mentions of Islam in Chicago are from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE), though Muslim presence in the United States predates the exposition through the lives of enslaved Africans and Middle Eastern and South Asian merchants and sailors in the 18th and 19th centuries. At the fair, Muslim migrants from Algeria, Egypt, Nubia, Persia, Sudan, Tunisia, Turkey, and India came to visit and work, with some staying and settling in the city.

Exterior and interior views of the Turkish mosque at the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893. CHM, ICHi-020531 (left) and ICHi-093978 (right).

The WCE hosted some of the earliest purpose-built mosques in the country, with three total—one each in the Ottoman, Egyptian, and Javanese villages on the Midway Plaisance. Though the WCE officially opened after the month of Ramadan, there is documented awareness of the month of fasting. The WCE mosques hosted other religious rituals, including regular public calls for prayer, known as the adhan, and were closed to spectators during prayer times. As with most buildings constructed for the WCE, the mosques were only temporary and no longer stand today.

Parliament of the World’s Religions, 1893. CHM, ICHi-062640

Further awareness of Islam came at the WCE’s ancillary interfaith gathering, the Parliament of the World’s Religions. Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb, a Euro-American convert to Islam and founder of the Islamic Propaganda Movement, represented the Muslim perspective during the 16-day gathering.

Built in 1922, Al-Sadiq Mosque is one of the earliest purpose-built ones in the country and is home to the historic Ahmadiyya community, Chicago. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

The 20th century saw major growth and expansion of Chicago’s Muslim communities. In the early 1900s, one of the country’s oldest Muslim organizations was established by the Chicago Bosniak community, the Muslimansko Podpomagajuce Drustvo Dzemijetul Hajrije (Muslim Mutual Aid Association and Benevolent Society). The 1920s saw the founding of Chicago’s Ahmadiyya community through the missionary efforts of Mufti Muhammad Sadiq from India and the establishment of the first Ahmadi Mosque. The Nation of Islam, founded by Wallace Fard Muhammad in Detroit, found home in Chicago in the 1930s through the leadership of Elijah Muhammad. The years following World War II saw an influx of immigrants and refugees from the Middle East and South Asia, yet again growing and shifting community presence.

Mosque Maryam in Chicago is an example of a former Greek Orthodox Church that was repurposed as a mosque by the Nation of Islam. CHM, ICHi-175829. Photograph by Timothy Paton Jr.

As communities formed around the city, places of gathering became essential. Mosques and Islamic centers were organized, many in adapted buildings such as homes, storefronts, and former churches or synagogues. Communities constructed buildings to house daily prayers, weekly Jum’ah (Friday prayer service), schools, and other community services. The need for more space shifted buildings from Chicago to the suburbs. Today, there are about 100 mosques in the Chicago metro area with more now in the suburbs than within city limits.

The Islamic Education Center in Glendale Heights, Illinois, is an example of a purpose-built mosque in the western suburbs. The community holds interfaith iftar dinners during Ramadan. CHM, ICHi-175837. Photograph by Timothy Paton Jr.

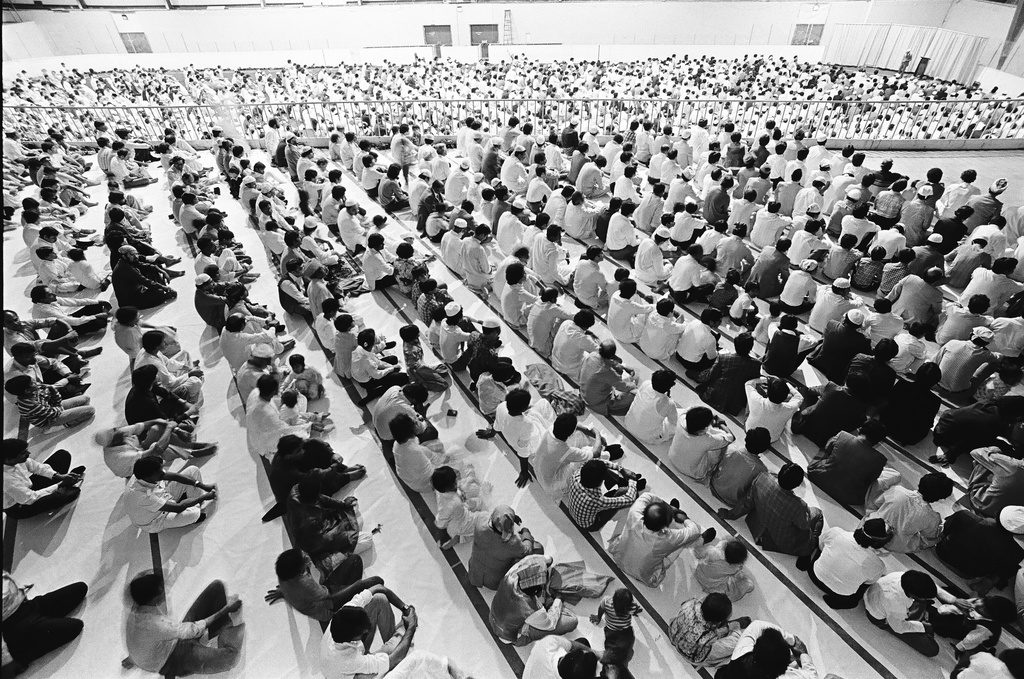

While many community activities take place within the walls of mosques or education centers, for the end of Ramadan, communities sometimes host Eid celebrations in large, outdoor spaces or in rented auditoriums or stadiums. These Chicago Sun-Times images are from such a community gathering hosted by the Islamic Foundation at the Odeum Expo Center in Villa Park in 1983.

Exterior view of the Odeum Expo Center in Villa Park, Illinois, 1983. ST-19041602-0012, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM

Communal prayer during Eid al-Fitr, hosted by the Islamic Foundation at the Odeum Expo Center. ST-19041602-0074, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM

The Islamic Foundation (IF) was established in 1974 by local families under the direction of community leaders including Abdul Hameed Doger and Dr. Zia Hassan to serve the Muslim community of Chicago’s western suburbs. IF began meeting in rented facilities in 1975. By the 1980s, its membership had grown to 200 families, and IF purchased the former Madison Elementary School building in Villa Park. The Eid gathering in these images took place during this transitional period, and thousands of people came to the rented auditorium to celebrate together. The community later started a full-time Islamic school in 1988. By the 1990s, the foundation had more than 2,000 members and a large expansion project took place. Today, the IF is one of the largest Islamic centers in the country and includes the IF Masjid, a library, community center, banquet hall, meeting rooms, as well as an expanded IF School. Dr. Shakeela Hassan, local community leader and widow to Dr. Zia Hassan, describes Ramadan as a time when generosity and charitable giving are at their peak, providing the opportunity to do good in the community—a spirit reflected through the Islamic Foundation’s history.

Above and below: Attendees at Eid al-Fitr at the Odeum Expo Center. ST-19041602-0015 and ST-19041602-0042, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM

Additional Resources

- See more images of the Eid al-Fitr celebration in Villa Park

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entries on Muslims, Bosnians, Egyptians, Palestinians, Syrians, and Pakistanis

- Listen to oral history interviews from our project American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago

- View images that were featured in our past exhibition American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago

In 1987, Congress officially designated March as Women’s History Month to commemorate, learn about, and reflect on women who have been history makers on their own terms. Chicago has had its fair share of influential women who have shaped not only the city, but the entire nation through their activism and work. In an effort to bring these narratives to the forefront, we’re proud to present this reader highlighting stories, exhibitions, and resources from the Chicago History Museum that elevate the stories of three of Chicago’s most notable women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—Lucy Parsons, Jane Addams, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett—in one convenient place.

Portrait of Mrs. Lucy E. Parsons, arrested for rioting during an unemployment protest at Hull-House in Chicago, January 18, 1915. DN-0063954, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Lucy Parsons (1851–1942)

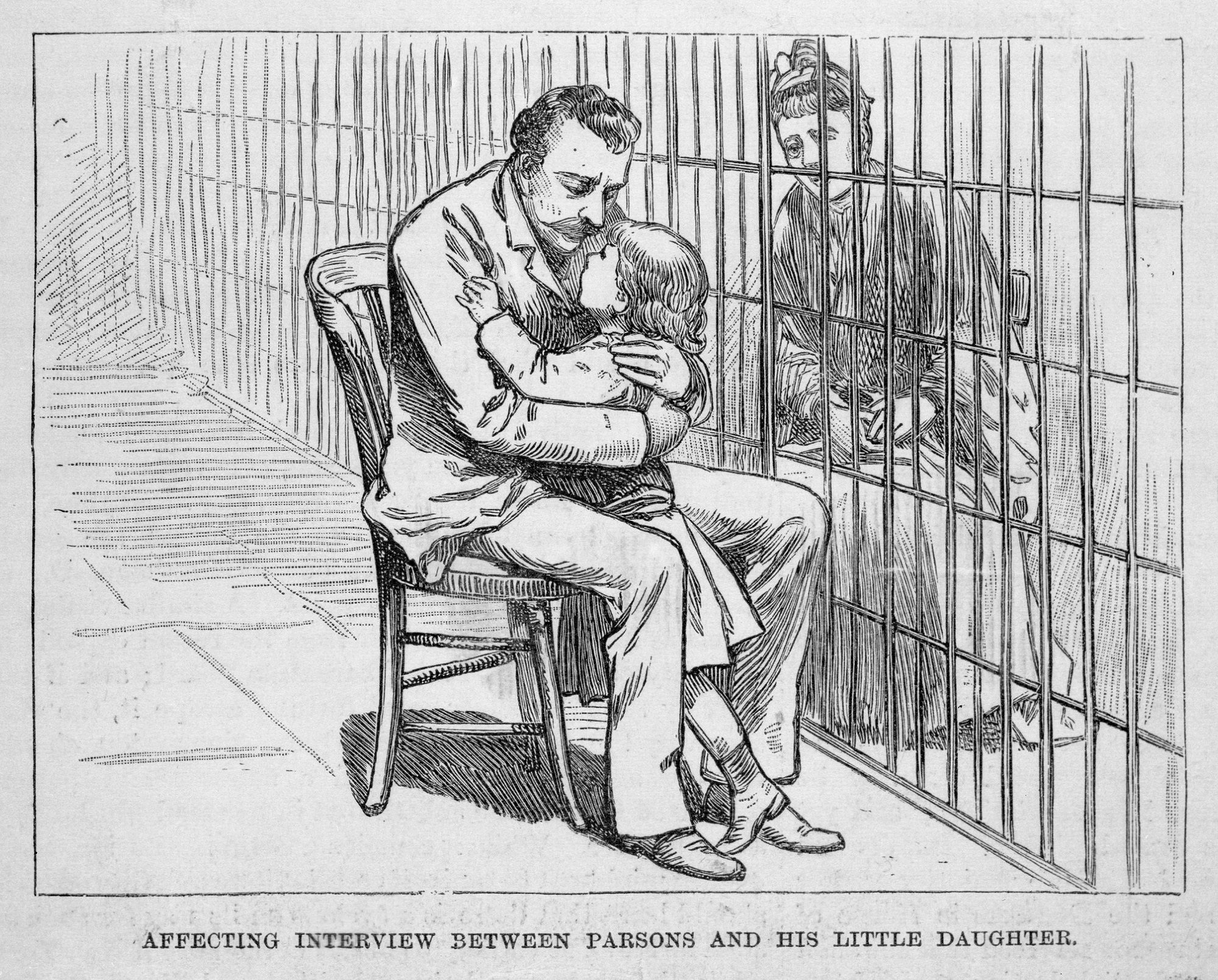

Supposedly once described by the Chicago Police Department as “more dangerous than a thousand rioters,” Lucy Eldine Gonzales Parsons was a labor activist and organizer, a renowned orator, and perhaps most controversially during her time, a person of mixed heritage who claimed Mexican and Indigenous ancestry. She was the widow of Albert Parsons, one of the men hanged for his role in the Haymarket Affair.

Sketch titled “Affecting interview between Parson’s and his little daughter” showing Albert Parsons hugging daughter in jail after Haymarket Affair arrest, Chicago, 1887. Published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, November 12, 1887. CHM, ICHi-003672

Blog Post

CHM curatorial intern Brigid Kennedy’s blog post “A Fighter for Workers’ Rights” recounts the life of labor organizer Lucy Parsons.

The Dramas of Haymarket

This project highlights holdings from CHM’s collection related to the events before, during, and after the riots of 1886.

Chicago History magazine, vol. 15, no. 2 (summer 1986)

Parsons is mentioned numerous times in this issue highlighting her work as a publisher and radical organizer following the execution of the Haymarket martyrs. This entire issue is dedicated to the history and legacy of the Haymarket affair in the city.

Studs Terkel Radio Program about Labor History and Lucy Parsons

Listen as Studs Terkel talks with Irwin St. John Tucker about socialist causes in Chicago and historian Carolyn Ashbaugh about her book Lucy Parsons: An American Revolutionary.

Studs Terkel Radio Program about the Haymarket Affair

Studs Terkel talks with authors and historians Bill Adelman, Paul Avrich, Carolyn Ashbaugh, and Bill Neebe, the grandson of Haymarket defendant Oscar Neebe. The interviewees create a timeline of the events leading up to the Haymarket Affair including the German immigrants’ living situations, unions and strikes, and police brutality and corruption.

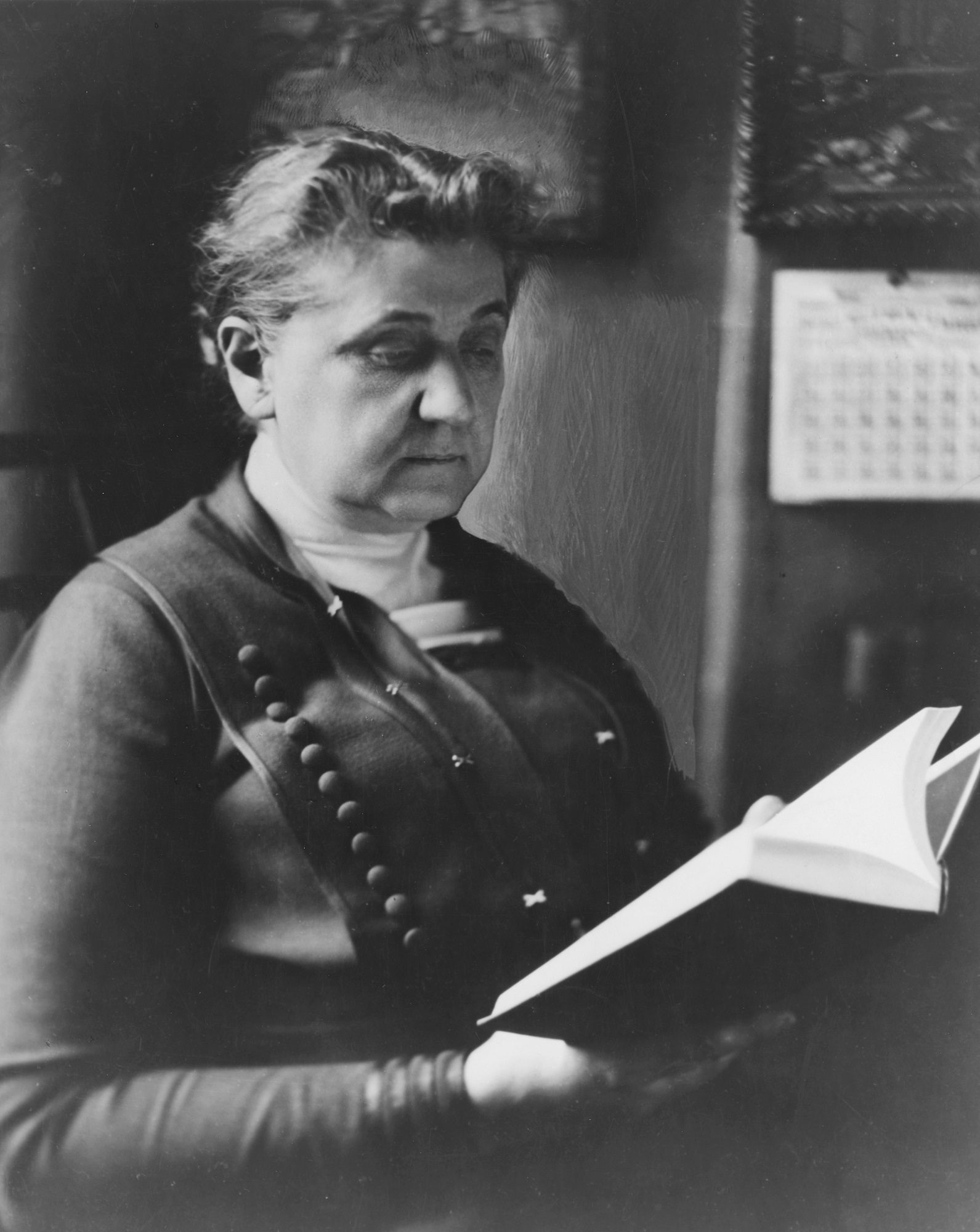

Portrait of Jane Addams, seated, reading a book, 1915. CHM, ICHi-026679

Jane Addams (1860–1935)

Jane Addams was a woman of many hats. In her role leading Hull-House, the Nobel Peace Prize winner and author was a social worker, housing activist, public health advocate, and the subject of an FBI investigation for so-called suspicious, and potentially treasonous, activities. Under her leadership, Hull-House became the most important settlement house in the United States.

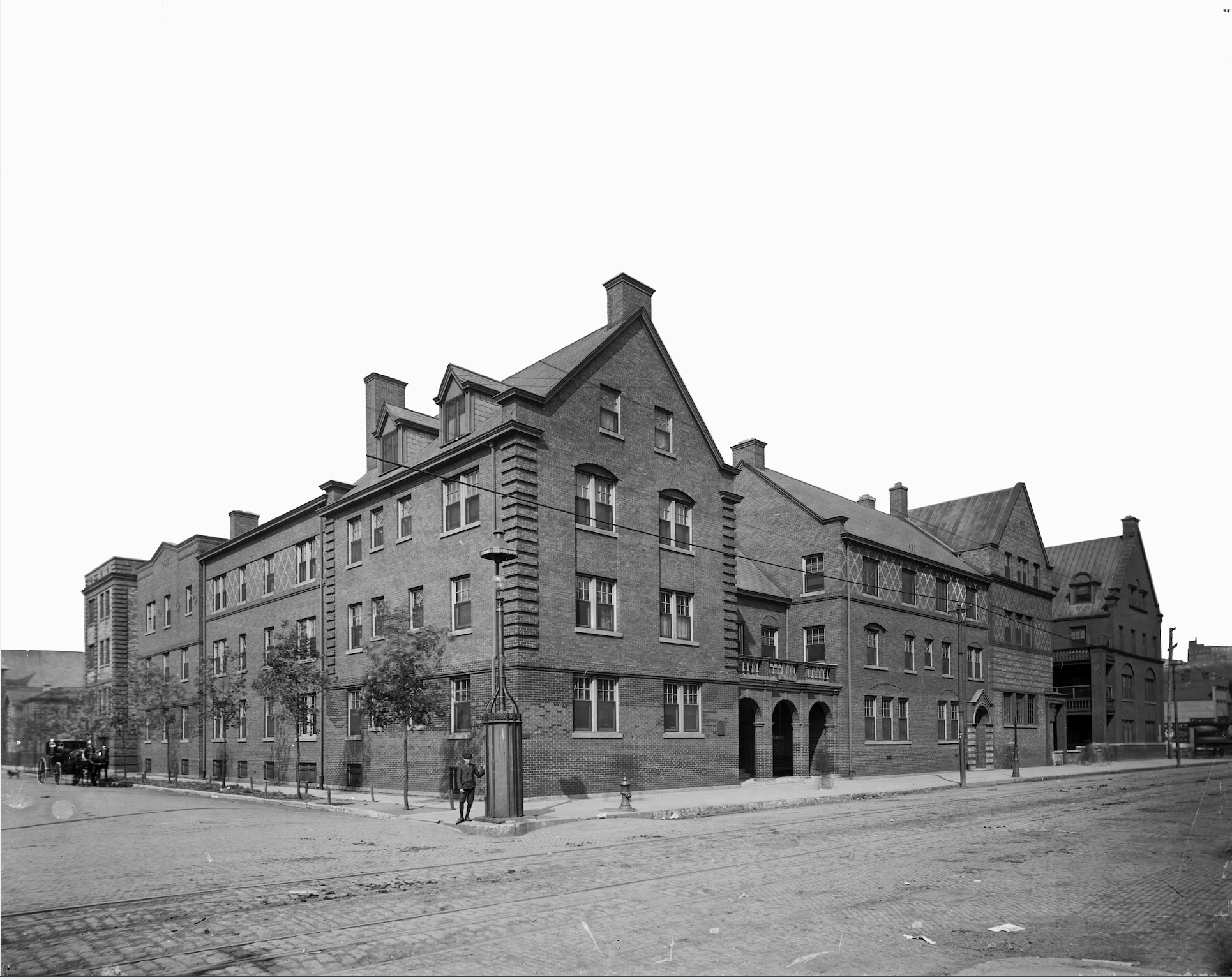

Exterior view of Hull-House, Chicago, c. 1905. CHM, ICHi-019228; Barnes-Crosby Company, photographer

Digital Chicago – Jane Addams: Chicago’s Pacifist

In this digital project led by Professor James J. Marquardt of Lake Forest College, learn about Jane Addams’s lesser-known international peace advocacy before, during, and after World War I.

Encyclopedia of Chicago – Hull-House

Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Hull-House, Chicago’s first and the nation’s most influential settlement house, which was established by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr on the Near West Side on September 18, 1889. Also included is an excerpt from Addams’ memoir, Twenty Years at Hull-House.

Chicago History magazine, vol. 12, no. 4 (winter 1983‒84)

The essay “Hull-House as Women’s Space” by Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz presents an in-depth analysis of the importance that the architecture of Hull-House had for its residents.

Studs Terkel Interview with Jessie Binford

Jessie Binford was a social worker who worked closely with Jane Addams at Hull-House. Listen as she talks with Studs Terkel about Addams’s life, the creation of Hull-House and the associated buildings, and how deeply in need they were of the help.

Portrait of Ida B. Wells-Barnett, 1920. CHM, ICHi-012867

Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862–1931)

Born enslaved in Mississippi during the Civil War, Ida Bell Wells spent her career as a journalist protesting and investigating lynchings, which ultimately brought her to Chicago for her own safety. It would be here that she would take her activism to a global stage, speaking to audiences abroad about the horrors of the Black experience in America. At home, she continued her work as a reporter and used influence to lobby for women’s rights issues, especially for non-white women.

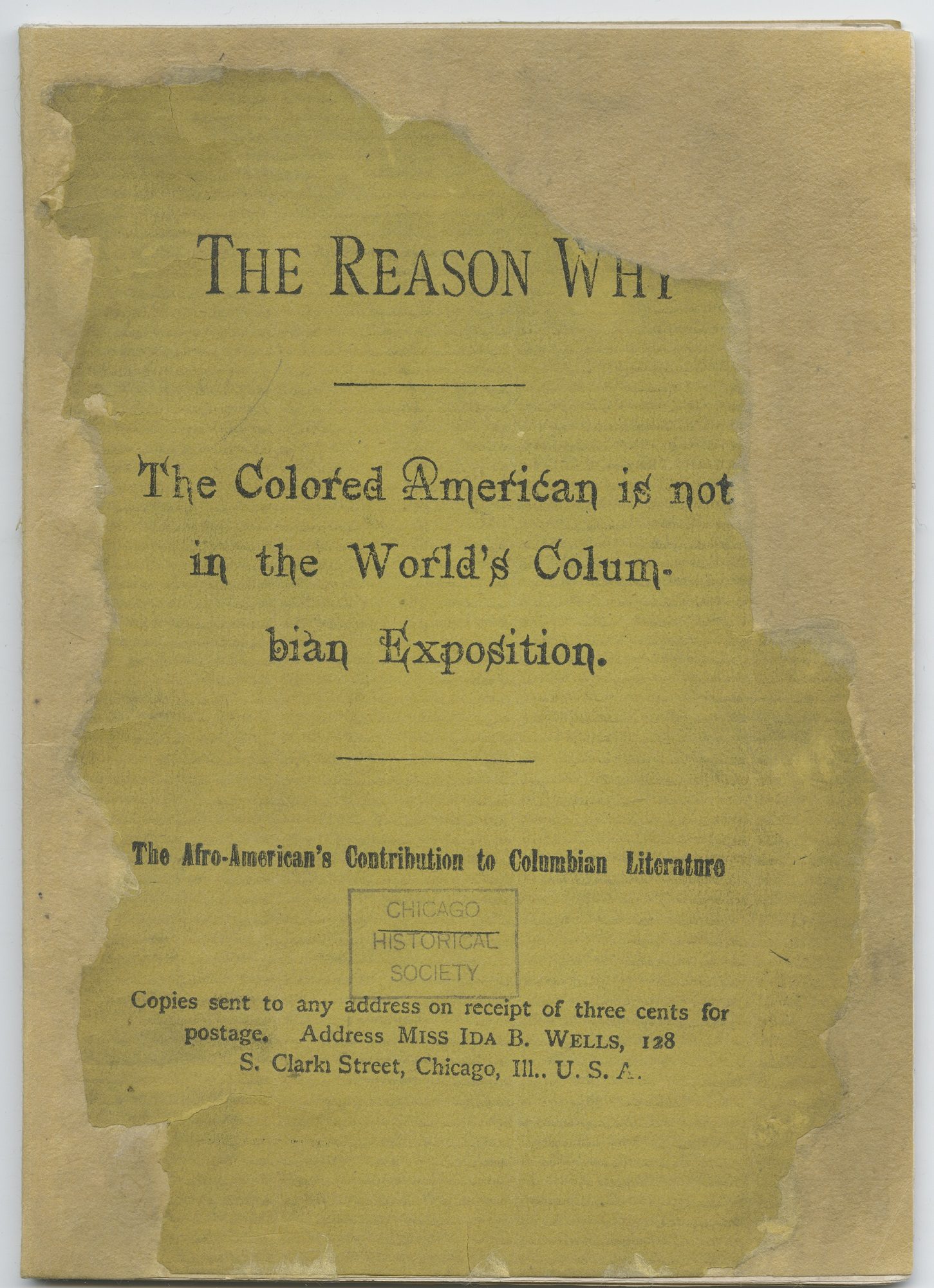

Cover of the booklet The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition: The Afro-American’s Contribution to Columbian Literature, by Ida B. Wells, published in Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-040939

Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote

As one of the staunchest defenders of democracy during her time, the multifaceted story of Ida B. Wells-Barnett is present in a number of the modules that make up this online experience about women’s activism in Chicago to secure the right to vote—and beyond.

The Voids Project Zine

As a supplement to Democracy Limited, this zine was put together by a group of teens from across Chicagoland to document the social and organizing work of prominent Black women in Chicago, including Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and the places they supported.

Chicago History magazine, vol. 25, no. 3 (fall 1996)

The essay “The Brotherhood” by Beth Tompkins Bates chronicles the early work in organizing the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. This organization drew on the efforts of many of Chicago’s women social activists, such as Irene McCoy Gaines, Mary McDowell, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett.

Studs Terkel Interview with Alfreda Wells

Listen as journalist Studs Terkel speaks with Alfreda Wells, the youngest child of Ida B. Wells-Barnett, about her mother’s life and work as an investigative journalist and strong champion of civil and women’s rights.

Additional Resources

Beyond Parsons, Addams, and Wells-Barnett, Chicago history is full of women who made history their own.

Walking Tour | Democracy Limited – Chicago Women & the Vote

Go at your own pace and see where history was made here in Chicago.

Facing Freedom in America Exhibition

The Votes for Women collection contains a number of primary source materials that help interpret the contributions and leadership of Chicago women to a number of struggles in the fight for equality and suffrage.

CHM Blog – Women’s History

Explore the “women’s history” tag on CHM’s blog to read more stories of local women who made history.

To mark the start of Lent, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman talks about the meaning of ashes on Ash Wednesday and shares a brief history of Chicago’s Holy Name Cathedral.

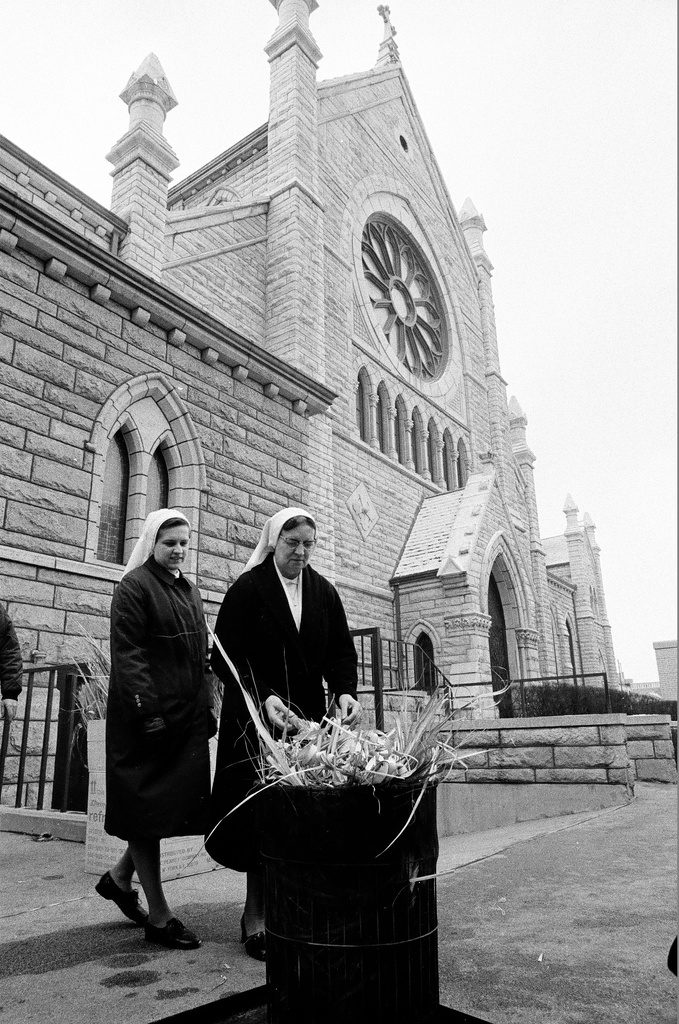

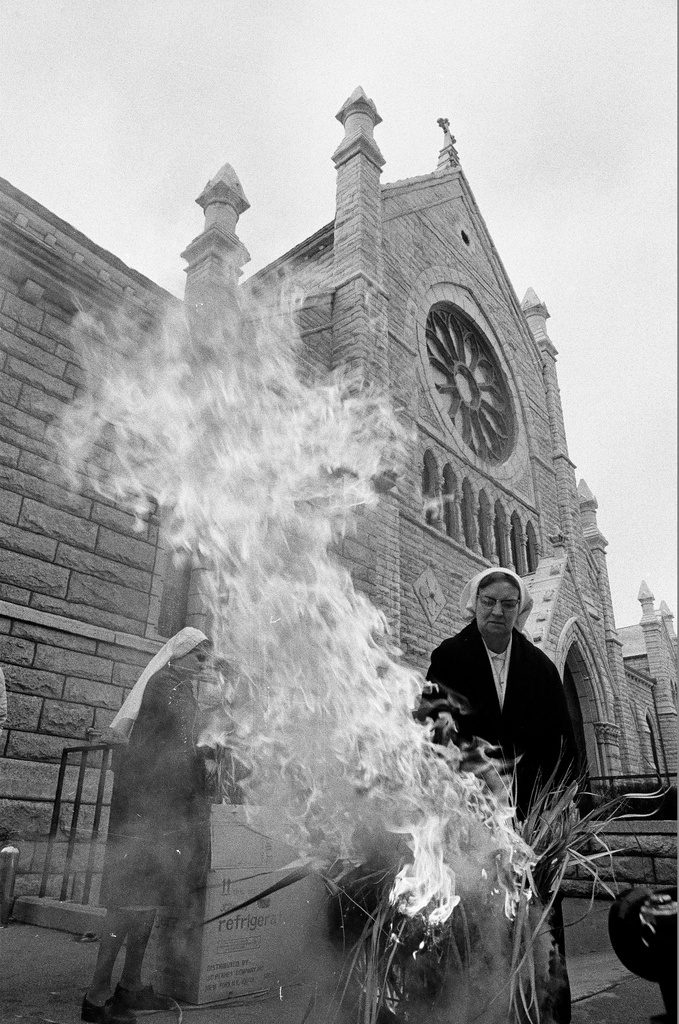

Sister Laurienne Normand (right, wearing glasses) burning palms for Ash Wednesday at Holy Name Cathedral, 730 N. Wabash Ave., Chicago, 1975. ST-40002014-0015, ST-40002014-0009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM.

Wednesday, February 22, 2023, marks the beginning of the Lenten season for many Christians. Beginning on Ash Wednesday, Lent is observed for forty days as a time of introspection, symbolic fasting, personal sacrifice, and preparation for Easter Sunday. In Catholicism, this takes form through abstaining from eating meat on commemorative days and Fridays.

Ash Wednesday mass at Holy Name Cathedral, Chicago, 1971. ST-60000886-0018, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM.

Ash Wednesday derives its name from the ritual of a priest or pastor ceremonially placing ashes on the foreheads of worshippers, often in the shape of a cross. This is accompanied by saying, “Remember that you are dust, and unto dust you shall return,” a nod to the Biblical verse Genesis 3:19 and reminiscent of the phrase often spoken at Christian funerals “ashes to ashes and dust to dust.” The ashes used in services come from burned palm branches and have material symbolism. In Christian tradition, the palm is closely associated with the person of Jesus through the biblical story of his entry to Jerusalem commemorated on Palm Sunday, with the palm branch itself an ancient symbol of victory, peace, and eternal life.

Priest and nuns along with schoolkids, burning palms for Ash Wednesday at Holy Name Cathedral, Chicago, 1975. ST-40002014-0004, ST-40002013-0014, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM.

Palm branches used in celebrating Palm Sunday are saved from the previous year and then ritually burned to create ashes for the next year’s services. Holy Name Cathedral in Chicago’s Near North Side neighborhood has held an annual “burning of the palms” event the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday for decades. Saved palms are brought to Holy Name’s courtyard on “Shrove Tuesday” (also known as “Fat Tuesday”), a day that celebratorily bridges the passing of the last year into the reflective start of Lent the next day. In a 1975 Chicago Defender article, Rev. James. J. Jakes of Holy Name notes the burning of palms as symbolic for the “burning out of our lives those things that [should] not be there.”

Hand-colored slide showing the exterior of the Church of the Holy Name ruins after the Great Chicago Fire, c. 1871. CHM, ICHi-176633.

The symbolism of renewal through ashes is very fitting for the legacy of Holy Name Cathedral. As the present seat of the Archdiocese of Chicago, it is the central church for one of the largest Roman Catholic Diocese in the country. The Chicago Diocese was founded in September 1843, just months after the city was formally established, and the Catholic community grew rapidly in tandem with the city. Just a few decades later, Holy Name’s predecessor congregations, the Cathedral of St. Mary and Church of the Holy Name, lost their buildings to the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

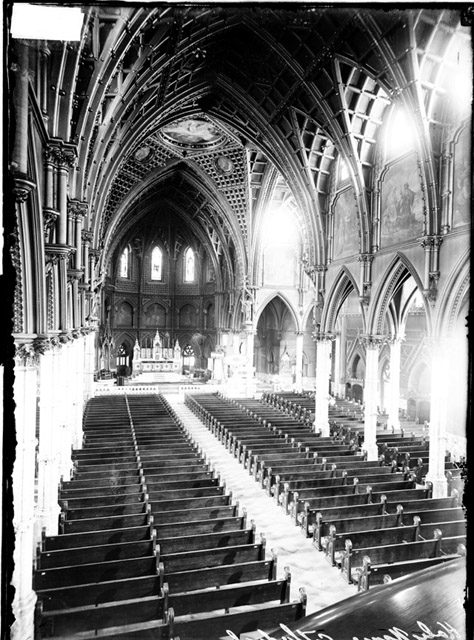

Holy Name Cathedral exterior and interior at 730 N. Wabash Ave., Chicago, 1909. DN-0007701 and DN-0007835, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM.

As the city itself is often compared to a phoenix rising from the ashes, so, too, is Holy Name in its postfire manifestation. For four years, the congregation met in a repurposed space while a new building was conceived and fundraised. By 1874, a stunning Gothic Revival structure arose from the former church site at State Street and Huron. Dedicated in 1875, the new Holy Name building was designed by Irish American Patrick Charles Keely, a favored architect of the American Roman Catholic Diocese who designed more than 600 churches, including a number of cathedrals. Keely looked to European stylistic trends purported by figures such as Augustus Pugin and John Ruskin to create an architectural language steeped in contemporary reinterpretations of medieval design. At Holy Name, the sanctuary’s wood interior is meant to recall the biblical Tree of Life through soaring archways and elaborate tracery.

Left: Renovation work being done on Holy Name Cathedral, 1969. ST-80004678-0012, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM. Right: Holy Name Cathedral, 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman.

Holy Name has undergone several repairs and alterations since its construction, including a massive renovation in 1968–69 to align the worship space with post-Vatican II theological shifts. More recently, fire and ash again took hold as repair work to the church’s ceiling in 2008–2009 resulted in an accidental attic fire. Five circles in the ceiling hold symbolic images, with the largest now featuring the Greek monogram “IHS” for the name of Jesus over the image of a phoenix. Holy Name states this choice of imagery as a multilayered symbol: for the death and rebirth of the cathedral building, for the city of Chicago, and the symbolic death and resurrection of Jesus as remembered throughout the Lenten season.

Additional Resources

- See more images of Holy Name Cathedral

- Listen to Studs Terkel discuss church architecture with William Cooley, a church architect, and Martin E. Marty, a theologian and scholar at the University of Chicago

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Roman Catholics

In 1913, a sturdy brick and limestone building was completed and opened to the public; standing at five stories tall, what would come to be known as the Wabash Avenue YMCA was the result of community fundraising from area residents and the Chicago philanthropist Julius Rosenwald of Sears, Roebuck & Co. fame. While the building served as a job training center, temporary housing for stockyard workers, and of course a center for physical recreation in a segregated city, the Wabash YMCA’s most enduring legacy comes from its association with Dr. Carter G. Woodson.

Exterior view of YMCA of Metropolitan Chicago Wabash Avenue Building with addition in the Douglas community area of Chicago, c. 1940. CHM, ICHi-174453

Born to formerly enslaved parents in 1875 in Virginia, Woodson would go on to graduate from the University of Chicago in Hyde Park and receive his doctorate in history at Harvard University in 1912. Three years later, in the summer of 1915, Woodson traveled to Illinois to attend the National Half Century Anniversary Exposition and The Lincoln Jubilee: 50th Anniversary Celebration. This exhibition in Chicago celebrated the semicentennial of the emancipation of enslaved African Americans in the US, highlighting the work and contributions to the nation by Black Americans across every aspect of society. In September of that year, Woodson convened a meeting with local leaders to form the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH, known today as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History) at the Wabash YMCA, with the goal of promoting Black history across Illinois and the US through educational programs and print materials.

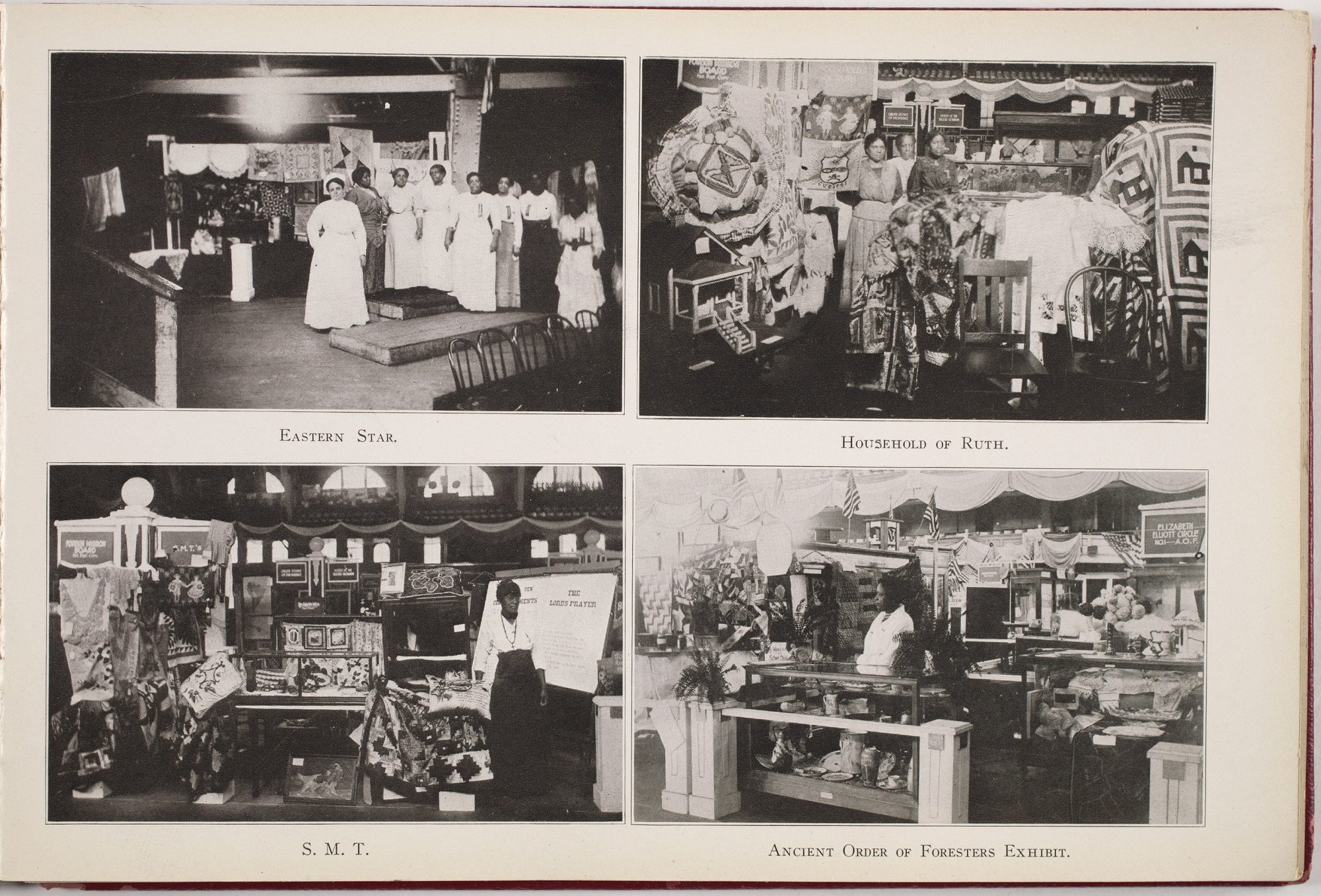

Page featuring photographs (clockwise from top left) of the Eastern Star, Household of Ruth, S.M.T., and Ancient Order of Foresters Exhibit at the National Half Century Anniversary Exposition and Lincoln Jubilee, Coliseum, Chicago, August 22‒September 16, 1915. Published in the Lincoln Jubilee Album: 50th Anniversary of Our Emancipation, compiled by John H. Ballard, 1915. CHM, ICHi-174447; John H. Ballard, photographer

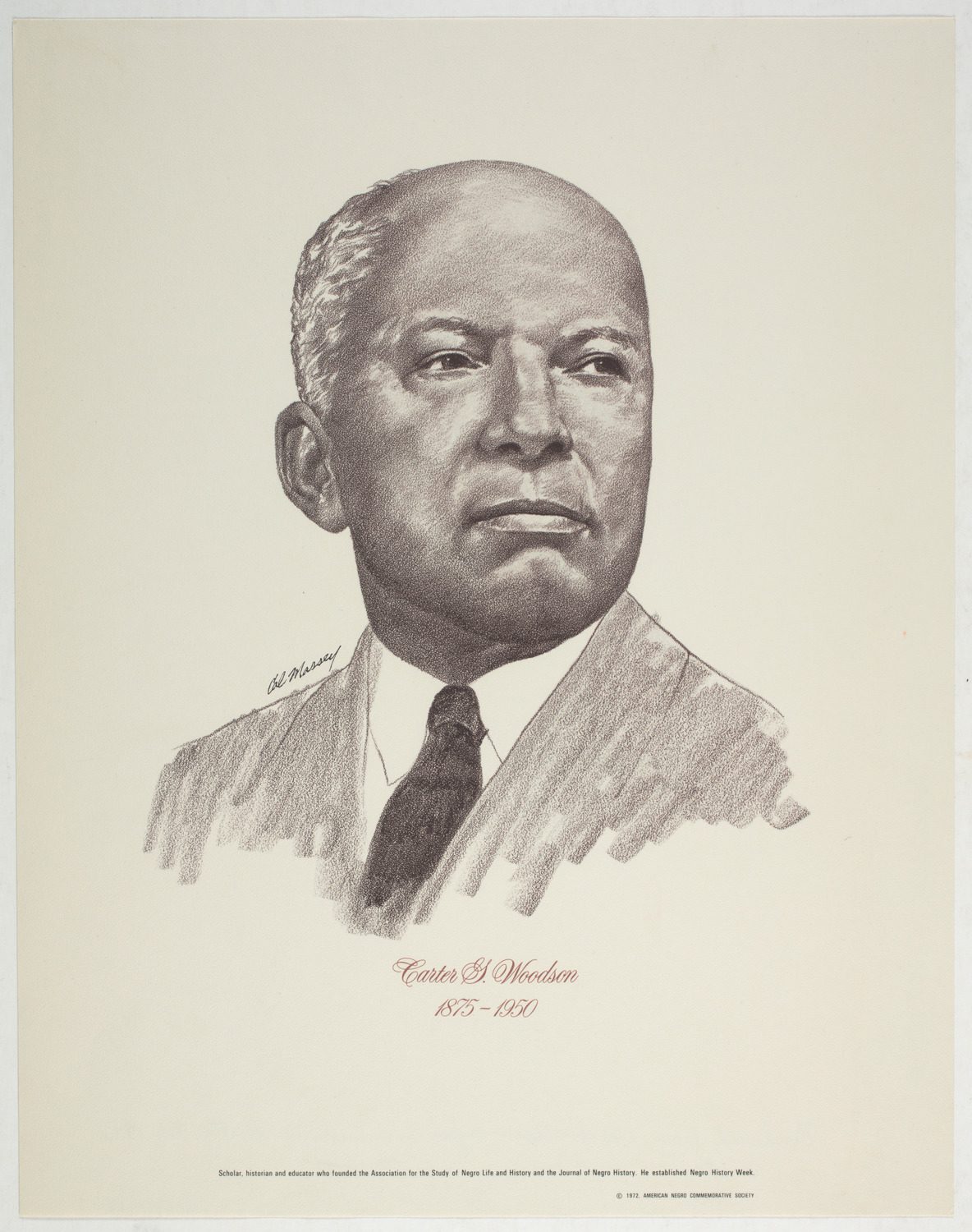

Portrait drawing, c. 1972, of Carter G. Woodson, scholar, historian, and educator. CHM, ICHi-031431; Cal Massey, artist © 1972 The American Negro Commemorative Society

Black History Month had a number of other iterations before it was a month-long celebration. It began in 1924 as “Negro History and Literature Week” and then was renamed “Negro Achievement Week.” The third and final name change would come in 1926, when a press release came forward announcing the celebration of “Negro History Week.” Woodson’s History Week received much fanfare across the country, since, due to the Great Migration, population numbers for Black Americans boomed across urban areas in the US. This meant a desire to adopt Woodson’s teachings and mission into school curricula and social clubs.

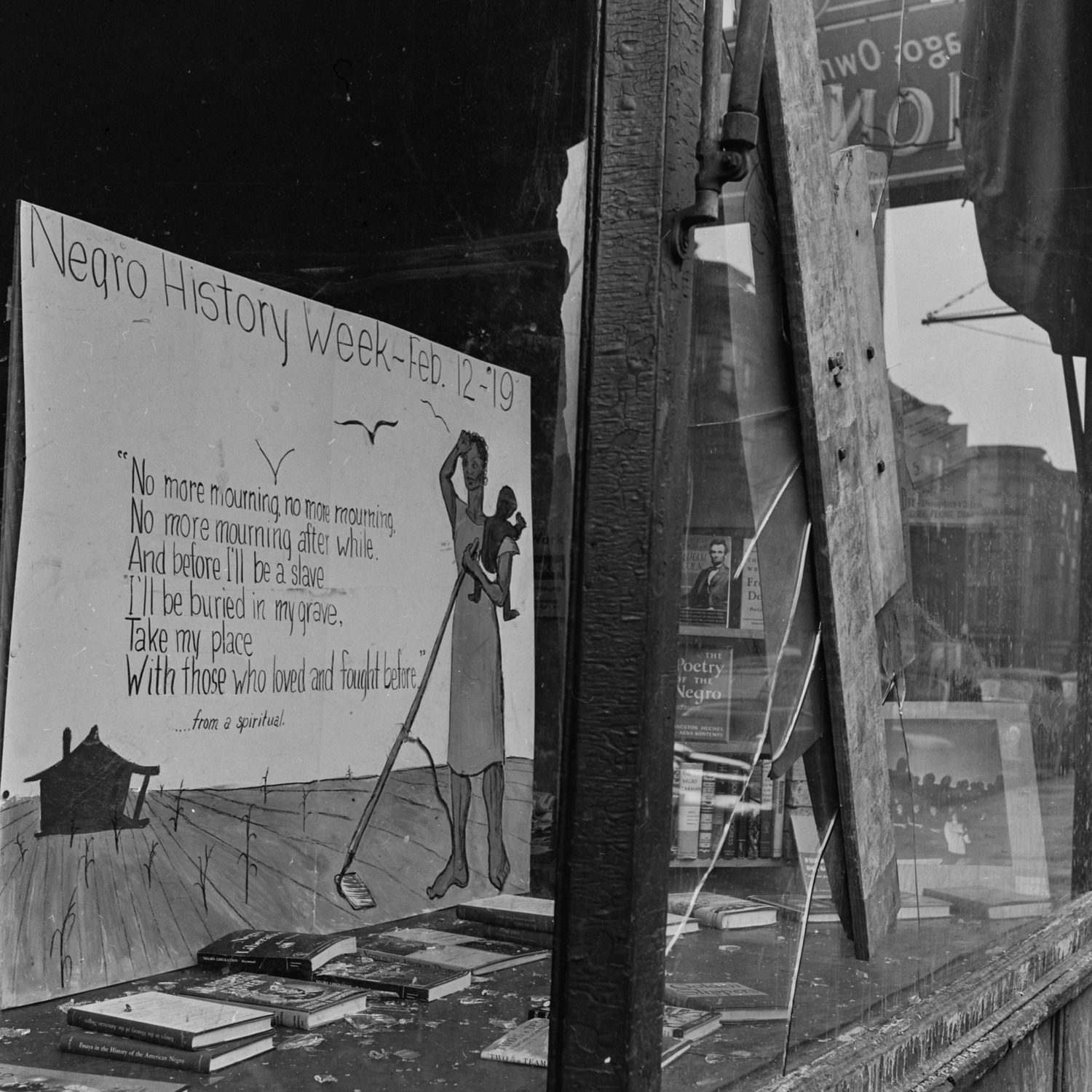

Sign for “Negro History Week” in the storefront window of Community Book Shop owned by Joan Place at 1404 E. 55th St., in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, February 1951. CHM, ICHi-087088; Mildred Mead, photographer

During all this movement, Chicago and the Wabash YMCA remained among the intellectual centers for Black History. Fortunately, the ASNLH counted among its ranks a Black librarian named Vivian G. Harsh, who worked for the Chicago Public Library system and who would eventually create one of the most robust archival Black history collections in the country, collecting books, ephemera, and other forms of cultural material related to the Black experience in the US. Harsh’s collection proved indispensable to the dissemination of knowledge for Woodson’s Negro History Week.

Woodson died following a heart attack in April 1950. He is interred at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Maryland. Twenty-five years after his passing, the Chicago Public Library system honored Woodson’s memory by opening a branch named after him on the South Side. This branch would also come to house the Vivian G. Harsh Collection of Afro-American History and Literature, ensuring that the collection and all its treasures would remain accessible to all those interested in Black history.

Federal recognition for Woodson’s celebration of Black history came a half century later, when during the 1976 celebration of the US Bicentennial, President Gerald R. Ford proclaimed every February to be designated as Black History Month. Ironically, Woodson hadn’t expected Black History Month to be a long-term observance, as he hoped Black history would simply be included as part of our national educational curriculum. The Wabash YMCA received its own recognition a decade later, when it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Today, the building is owned by The Renaissance Collaborative (TRC), a multifaith community organization that purchased the building while it was in a state of disrepair in the 1980s and, after a restoration, has turned the building into an affordable housing apartment complex, saving it from demolition.

Today, Black History Month is a national celebration that continues to honor the legacy of Black Americans and their contributions, whether scientific, cultural, or intellectual, to American society. While it serves as a time to look back and reflect on often complicated histories, it also offers an opportunity to reflect on possible futures.

Additional Resources

- Take a virtual tour of the Wabash YMCA

- Learn more about Chicago’s early Black populations in our two-part Google Arts & Culture project “Concert is Power”: Part 1 and Part 2.