Latest Posts

Celebration of Obon, 1963. CHM, ICHi-037492; Albert M. Hayashi, photographer

In 2023, the multiday Japanese holiday of Obon or Bon takes place August 13-16. This festival is a time to honor and remember the spirits of the deceased, including family members and ancestors. Though believed to have origins in the Buddhist All Souls Day, Obon is not exclusively Buddhist and is celebrated by many communities in Japan and beyond throughout the Japanese diaspora.

Women and girls dancing with parasols at the 19th annual Midwest Buddhist Church Obon festival, 1763 North Park Avenue, Chicago, July 5, 1963. ST-40001293-0010, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Many different activities take place throughout the four days of celebrations to honor and welcome the time of remembrance. Before it begins, many families clean their homes and prepare special meals. The celebration is most readily recognized by its glowing paper lanterns, which are lit to welcome the spirits of those who have passed. The first day of the festival is usually marked by tending to loved ones’ graves and cleaning memorial stones.

Two women and girl at the 19th annual Midwest Buddhist Church Obon festival, Chicago, July 5, 1963. ST-40001293-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Special dances known simply as Bon Odori (“Bon dance”) are usually performed on the second day of the festival and are a pivotal part of Obon celebrations. On the third day, toro nagashi (“floating lanterns”) are lit by the hundreds or sometimes thousands and released on water as a spiritual guide, with the fourth and last day serving to bid loved ones farewell until the next celebration.

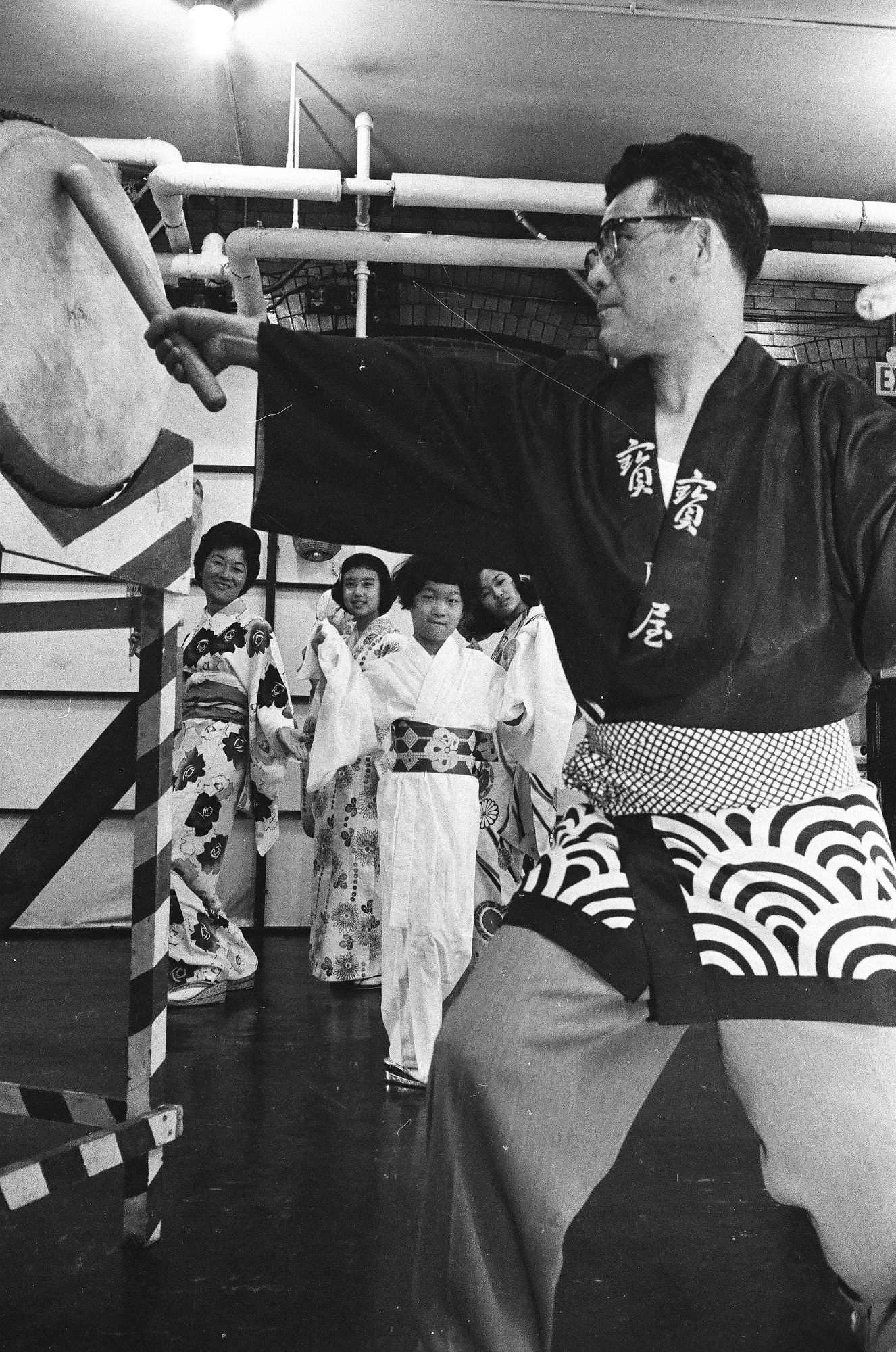

Dancers (left) and a taiko drummer (right) at the 19th annual Midwest Buddhist Church Obon festival, Chicago, July 5, 1963. ST-40001293-0003 (left) , ST-40001293-0004 (right), Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

This set of images from CHM’s Chicago Sun-Times photography collection are of an Obon celebration held at the Midwest Buddhist Church (now Midwest Buddhist Temple) in July 1963. According to news reports, three hundred men, women, and children danced that evening. Dancing took place in the streets with lanterns shining above. The festivities also included a costume parade and an Obon worship service “celebrating the oneness of the past, present and future” (Chicago Sun-Times, 1963).

The Midwest Buddhist Temple has roots in Shin Buddhism (known as Jodo Shinshu or “Pure Land” Buddhism). Early American Shin Buddhist communities formed in San Francisco due to Japanese immigration at the turn of the twentieth century, eventually becoming known as the Buddhist Churches of America. In the wake of World War II, thousands of Japanese Americans were forcefully relocated from the US West Coast in the 1940s, and many were imprisoned at “relocation centers” in rural locations around the country. At this time, Buddhism was seen as incongruous with “Americanness,” but communities fought to retain Buddhist beliefs and practices. Once released, community members looked to form new roots, with many coming to Chicago.

Midwest Buddhist Temple, 435 W. Menomonee St., Chicago, 2023. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman.

The Midwest Buddhist Temple was founded in Chicago in 1944, originally as the Midwest Buddhist Church, by Rev. Gyodo Kono. The community first met at the South Parkway Community Hall on the city’s South Side, then the Uptown Players, until moving to the Olivet Institute, a nonsectarian settlement house and community center on North Cleveland Avenue in the Old Town neighborhood. By 1948, the community bought and renovated their own building on North Park Avenue, dedicating it in September 1950. As they continued to grow and membership evolved beyond Japanese Americans, they recognized the need for a new purpose-built building. In 1971, they dedicated their current “Temple of Enlightenment.” Designed by Hideaki Arao, it draws from traditional Japanese architecture while using materials like concrete to withstand midwestern climate conditions and nod to its hybrid American identity and roots.

Additional Resources

- Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on Buddhists

- Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on the city’s Japanese community

- Research materials related to the Midwest Buddhist Temple in the Abakanowicz Research Center

Next week, Chicago welcomes the convening of the Parliament of the World’s Religions at McCormick Place from August 14–18, 2023. CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman writes about the event’s origins and its legacy as the genesis of the interfaith movement.

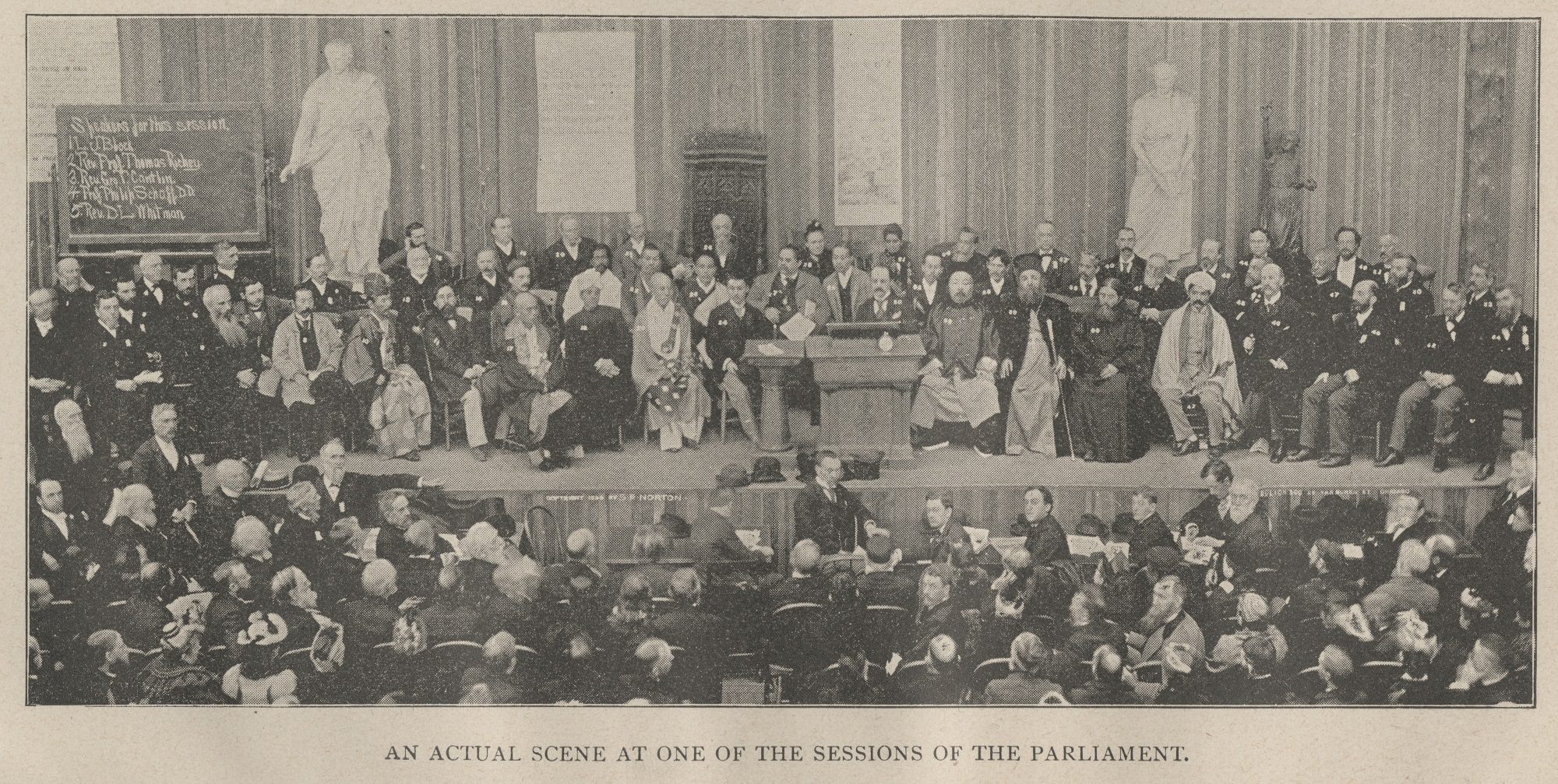

Group photo of scene at one of the sessions of the Parliament from the book The World’s Parliament of Religions, Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-062640

The Parliament of the World’s Religions (PWR) is a legacy of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE). The WCE saw a wide range of national and international representation through its pavilions and attractions. As a complement, the World’s Congress Auxiliary held numerous programs on a wide range of social and cultural topics with the slogan “Not things, but men,” alluding to the congress’s aims to have conversational programs rather than static displays.

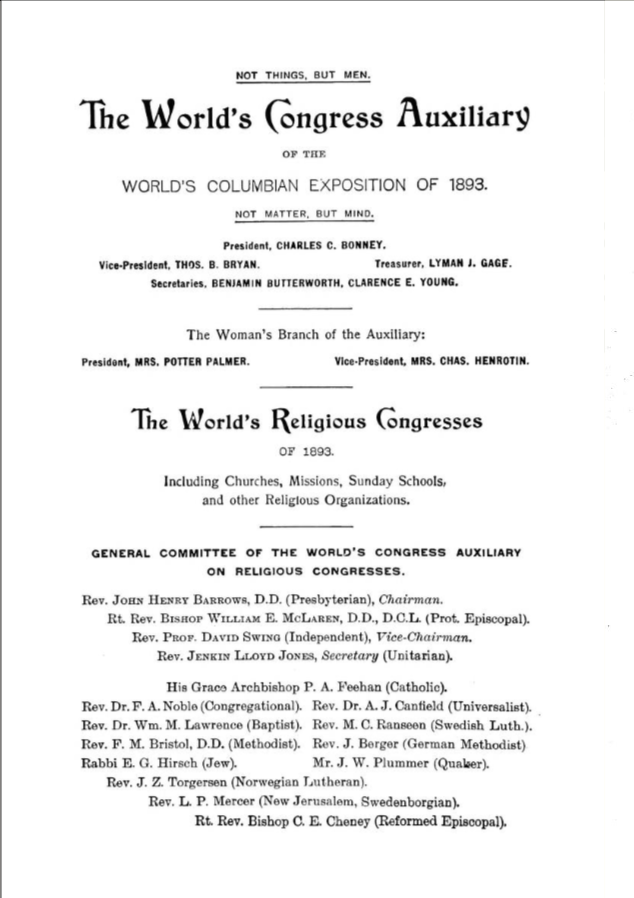

Cover page, Neely’s history of the Parliament of religions and religious congresses at the World’s Columbian Exposition / compiled from original manuscripts and stenographic reports. Edited by a corps of able writers. BL21.W8 N4

Throughout the run of the fair, more than 200 individual Congresses were held with nineteen departments represented. Just a sample of the covered topics include women’s progress, commerce and finance, art, government, medicine, and religion. The congresses were organized by Charles C. Bonney, a Chicago judge and author, who, in addition to legal writings, contributed several publications about the world’s fair congresses.

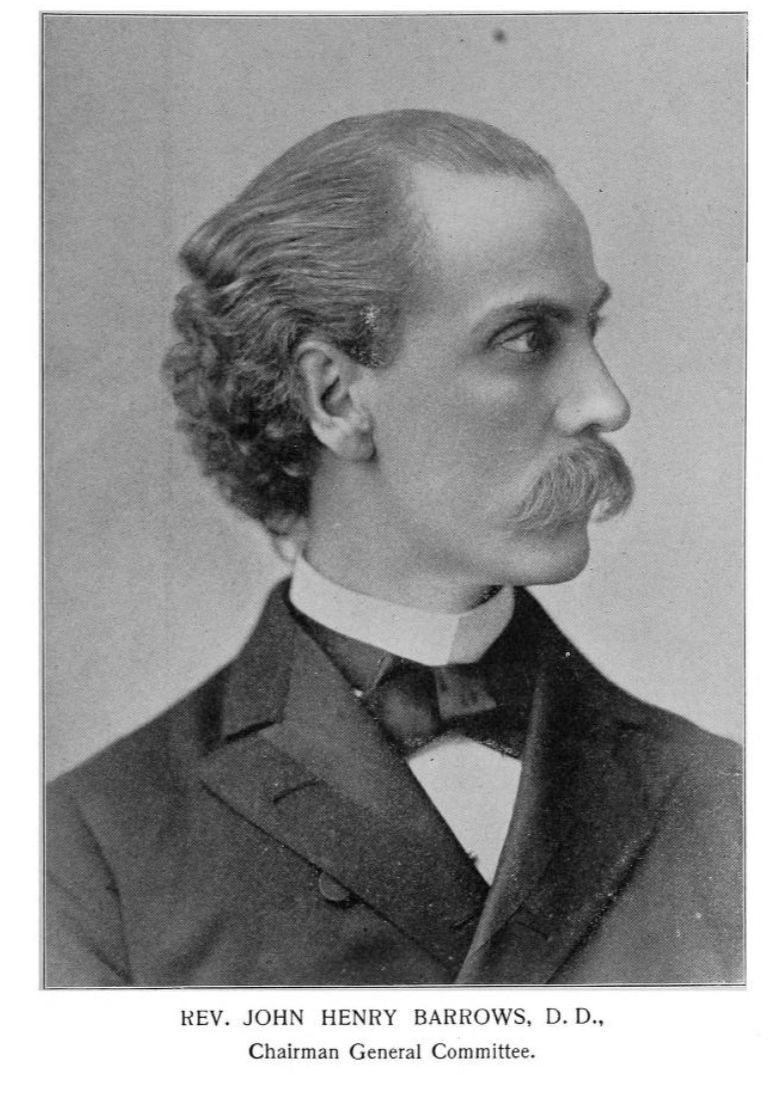

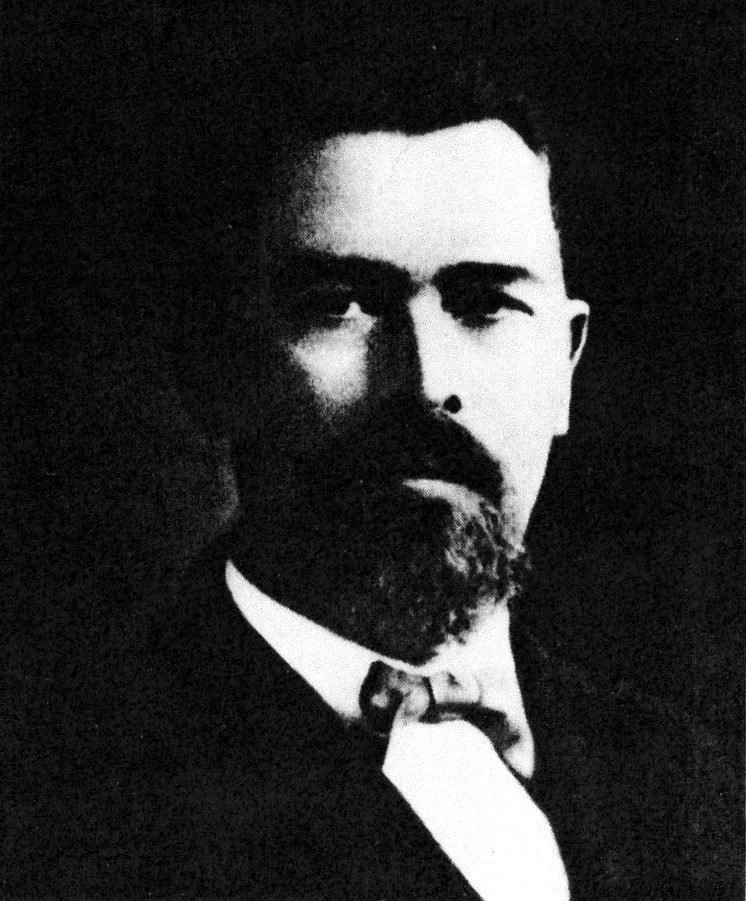

Perhaps the best known today, the Parliament of the World’s Religions was one such congress. Convened from September 11 to 27, 1893, the PWR is regarded today as the origin of the modern interfaith movement. Chicago-based Presbyterian minister Rev. John Henry Barrows served as chairman and, following the Parliament, compiled the event’s proceedings into a two-volume account through his Christian-centered lens.

Portrait of John Henry Barrows from Neely’s history of the Parliament of religions and religious congresses at the World’s Columbian Exposition / compiled from original manuscripts and stenographic reports. Edited by a corps of able writers, p. 18

Invitations to attend were sent globally. While some religious representatives were enthusiastically interested, others were cautiously apprehensive, and some abstained from attending altogether for reasons of belief. For example, the Archbishop of Canterbury declined attending, saying “the difficulties I myself feel are not questions of distance and convenience, but rest on the fact that the Christian religion is the one religion.”

Ten different religions were represented through presenting papers or speeches, including Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Taoism, Confucianism, Shintoism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Some of the event’s representatives and speakers included Swami Vivekananda (from India representing Hinduism), Anagarika Dharmapala (from Sri Lanka representing Buddhism), Virchand Gandhi (from India representing Jainism), Soyen Shaku (from Japan representing Zen Buddhism), Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb (from New York representing Islam), Henry Jessup (from the US, living in Lebanon, representing Presbyterianism), Pung Quang Yu (from China representing Confucianism), A. G. Bonet-Mary (from France representing Protestantism), Frederick Douglass (from Chicago representing the African Methodist Episcopal Church), Fannie Barrier Williams (from Chicago representing Unitarian Universalism), Antoinette Blackwell (from New York/New Jersey representing Unitarian Universalism), and Emil Hirsch (from Chicago representing Reform Judaism).

The Art Institute of Chicago, designed by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, at South Michigan Avenue and Adams Street, Chicago, 1892. CHM, ICHi-085800

As the PWR opened on the morning of September 11, 1893, a reproduction of the Liberty Bell ran ten times in symbolic honor of the ten traditions present. Representatives marched to the Hall of Columbus in the WCE’s Memorial Art Palace, today home to the Art Institute of Chicago, where a series of welcoming remarks and religious treatises were read.

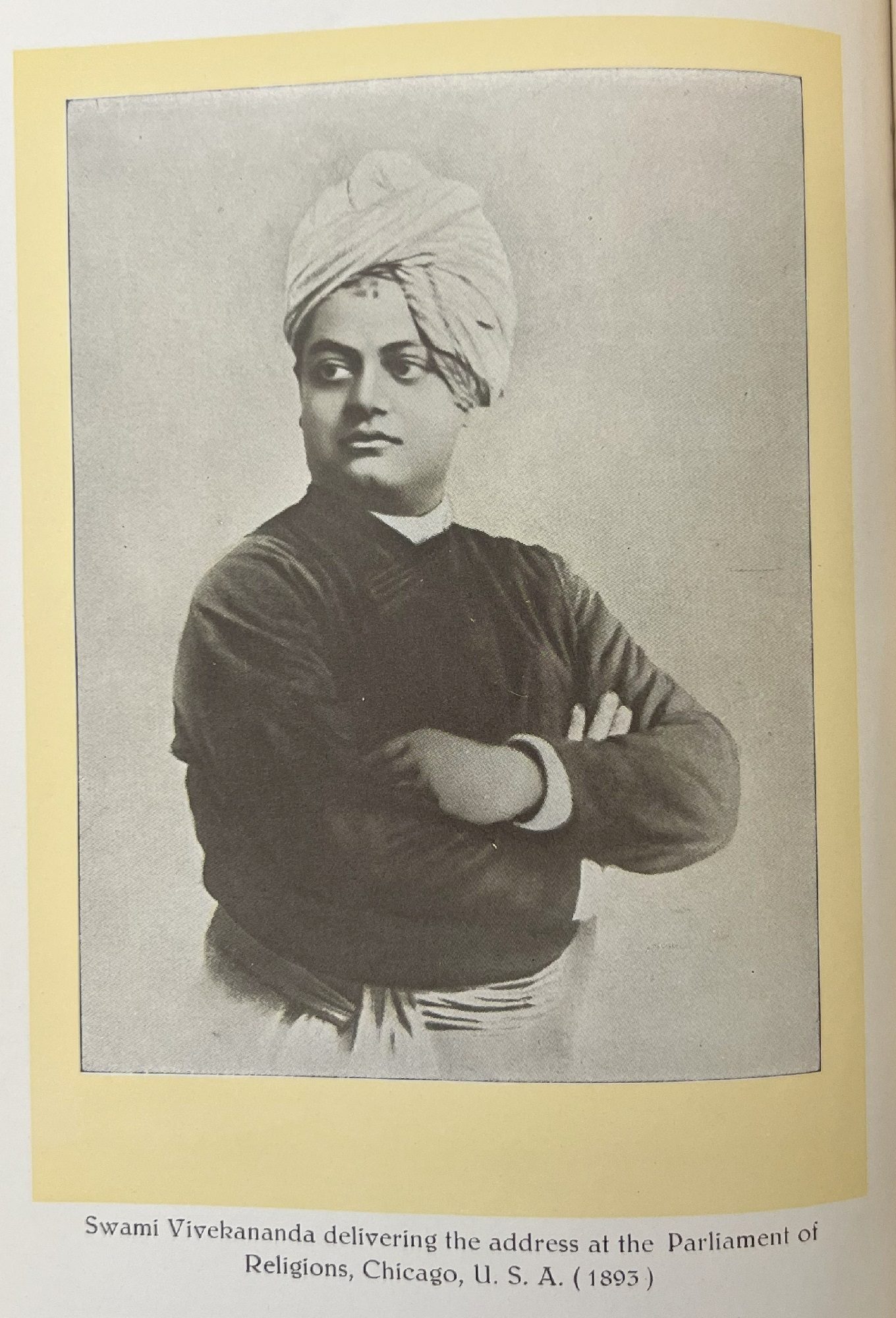

Portrait of Swami Vivekananda from The life of Swami Vivekananda / by his Eastern and Western disciples. X .V68L5 1955

Over the seventeen days of the parliament, speakers from across traditions and nations were given a platform to share about belief and the place of religion through their own lens. Swami Vivekananda (1863‒1902), founder of Ramakrishna Math and Ramakrishna Mission and the official representative of Hinduism at the PWR, gave an opening speech calling for global tolerance and an end to religious discrimination, saying:

Sectarianism, bigotry, and its horrible descendant, fanaticism, have long possessed this beautiful earth . . . But their time has come; and I fervently hope that the bell that tolled this morning in honor of this convention may be the death-knell of all fanaticism, of all persecutions with the sword or the pen, and of all uncharitable feelings between persons wending their way to the same goal.

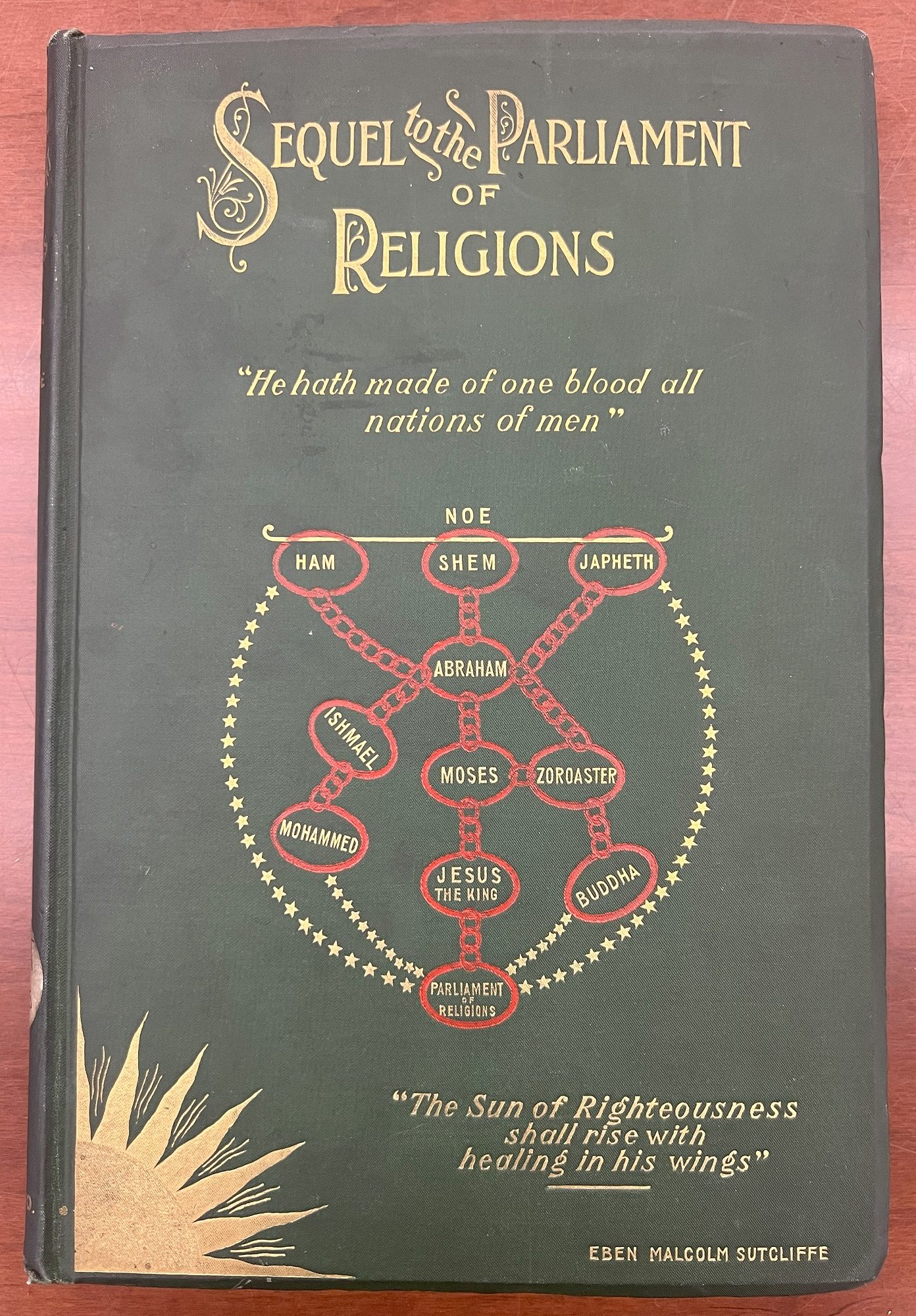

Front cover of Eben Malcolm Sutcliffe, Sequel to the Parliament of Religions, 1894. CHM Collections, F38T .S965

Though proclaimed a universal event, the gathering’s undertones presumed a white Christian religious conviction. For example, the Lord’s Prayer, coming from the New Testament Gospels of Matthew and Luke, was said at each day of the PWR’s convening. Additionally, while seen as socially progressive for its inclusion of non-Western traditions and representatives, there were notable imbalances in non-Christian representation. For example, the underrepresentation of African American Christian leaders, complete exclusion of Native American and Indigenous leadership and perspectives, and purposeful omission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.

In the years immediately after the fair, the PWR received much commentary and reflection but later largely fell out of public memory. In the 1970s and 1980s, religious scholarship began questioning why the groundbreaking strides toward religious pluralism present at the 1893 PWR had been mostly neglected in broader pluralist and comparative religious studies. Additionally, critical conversations were had regarding its lack of representation and inclusion, and the claims for its legacy of peaceful universality were questioned.

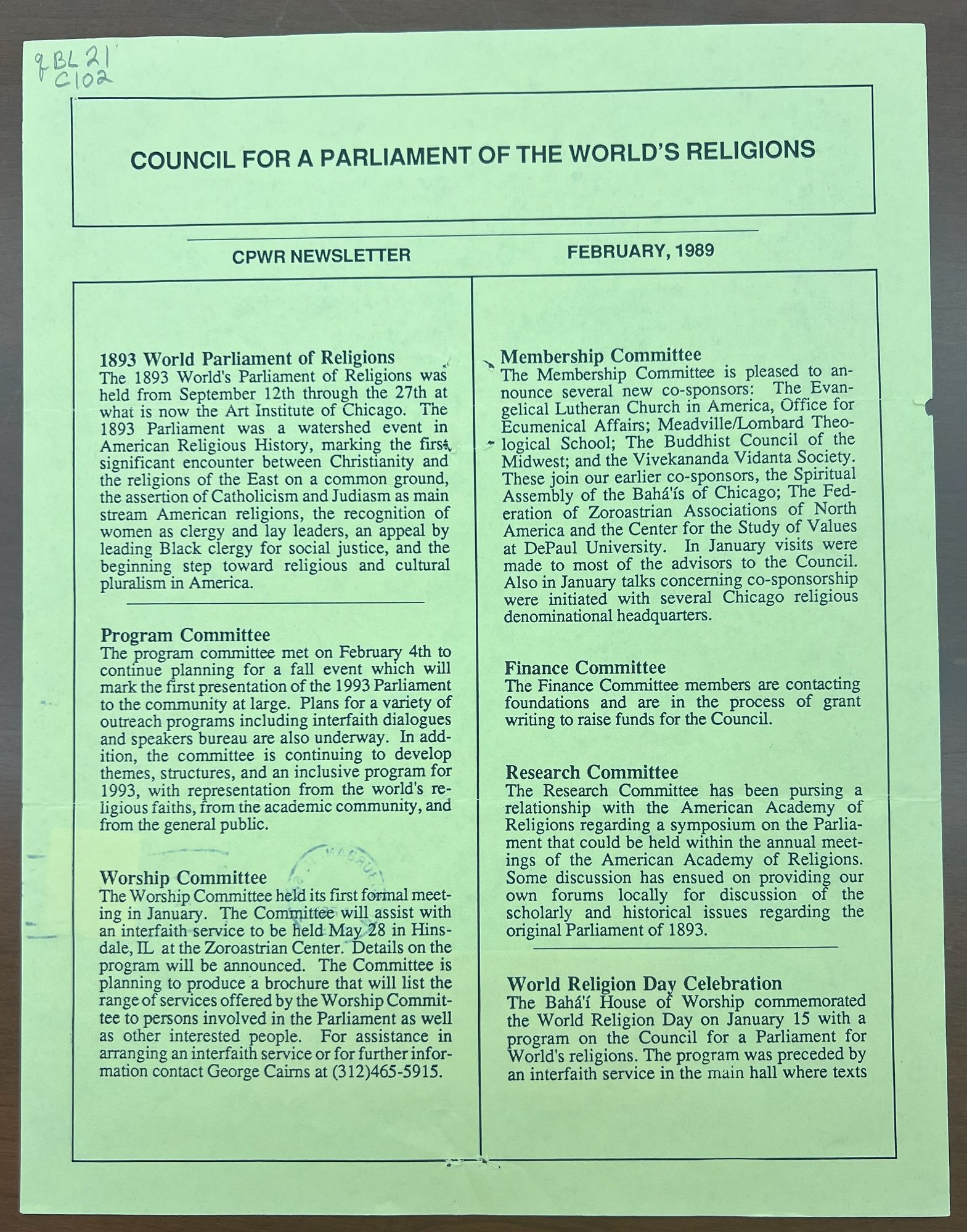

Newsletters published by the Council for a Parliament of the World’s Religions; CHM collections, BL21 .C102 OVERSIZE

In 1988, the Parliament of the World’s Religions was incorporated as an organization with the goal of continuing the legacy of the 1893 gathering through building a platform for interfaith dialogue. This included planning a 1993 convening to mark 100 years since its inauguration. The 1993 Parliament aimed to recontextualize interfaith work in the twentieth century and address the imbalances of the past. This was accompanied by the adoption and publication of The Global Ethic, which proposed a recommended set of shared moral and ethical principles beyond specific religious boundaries.

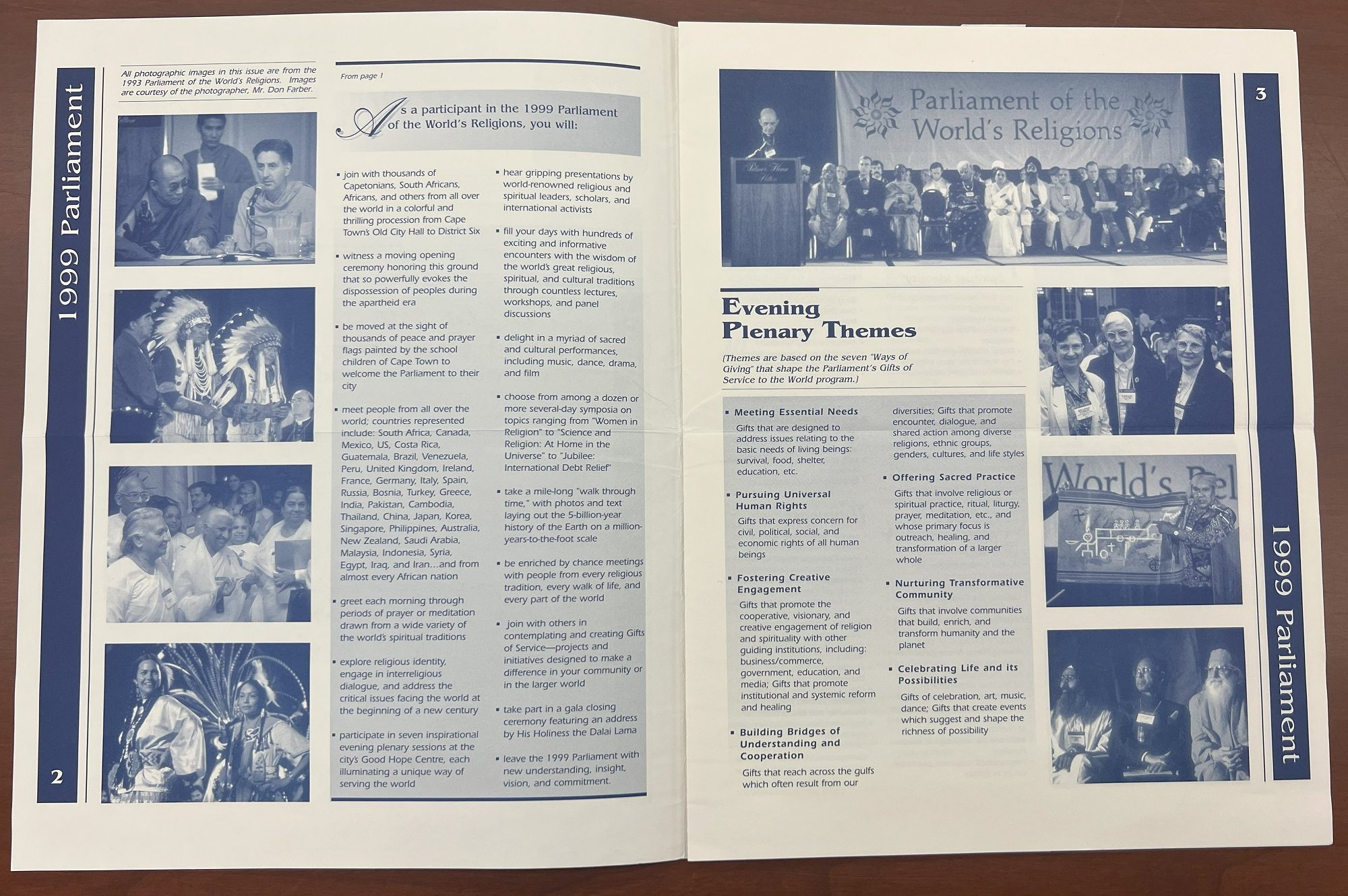

Newsletter describing the program for the 1999 Parliament of the World’s Religions in Cape Town, South Africa, BL21 .C102 OVERSIZE

The Parliament of World Religions has continued to meet in the intervening years, including in Cape Town, South Africa (1999); Barcelona, Spain (2004); Melbourne, Australia (2009); Salt Lake City, Utah (2015); Toronto, Ontario (2018); and virtually (2021). For the first time since 1993, it will return to Chicago in 2023. However, the rich and complex legacy of its first meeting remains present throughout the many communities who have called Chicago home before and beyond 1893.

Additional Resources

- Parliament of the World’s Religions in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Chicago’s influence on religion in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s interviews regarding theology, religion, and religious organizations

- Parliament of the World’s Religions

On August 2, 2023, two of Europe’s biggest soccer clubs—Chelsea Football Club of England and Borussia Dortmund of Germany—will face off at Soldier Field. The two clubs have played in Chicago in the past, with Dortmund playing Plymouth Argyle FC of England on May 7, 1954, and Chelsea playing an MLS All-Stars team on August 5, 2006.

A mention of Dortmund vs. Plymouth Argyle in the Chicago Daily News, May 7, 1954. Dortmund won the match 4–0.

Chelsea forward Andriy Shevchenko (left) and MLS forward Brian Ching play in the Sierra Mist MLS All-Star Game, Bridgeview Stadium (now SeatGeek Stadium), Bridgeview, Illinois, August 5, 2006. STM-0440-0854, Jon Sall/Chicago Sun-Times.

Since as early as 1905, when the Pilgrim Football Club of England played against a Chicago all-star team, international soccer clubs have often chosen Chicago as a major venue to exhibit some of the finest soccer talent in the world.

The city’s first organized soccer league can be traced back to spring of 1883, when the 39th Street Wanderers and the Pullman Car Works soccer teams kicked off at Pullman’s Lake Calumet athletic field complex. British and Canadian immigrants had played soccer in the city for years, but with the formation of the seven-team Chicago League of Association Football (CLAF), the city’s commitment to the sport gained national and international recognition.

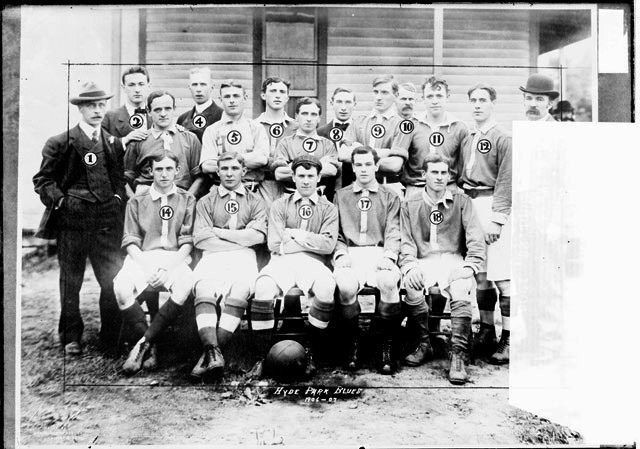

Hyde Park Blues soccer team, 1907. SDN-005468, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The CLAF flourished under the direction of its first president, Charles Jackson. In addition to the Wanderers and the Pullman clubs, other teams established by British immigrants included the Hyde Park Blues, Hyde Park Grays, Campbell Rovers, McDuffs, Swifts, Calumet, and a team of miners from the Braidwood coalfields. Interest in the league grew as local papers reported on an increasing number of teams, roster lineups, and scores. These early teams played two seasons per year, competed in friendly challenge matches against soccer clubs from visiting cities, and played annually for the Jackson Challenge Cup trophy. In 1901, looking to capitalize on soccer’s popular appeal, Charles Comiskey—better known as the founding owner of the Chicago White Sox baseball team—established a Midwest professional soccer circuit with teams from Chicago, St. Louis, Detroit, and Milwaukee. Midway through the season financial support deteriorated, and the league folded. Nevertheless, the sport flourished despite this setback, and by 1904 another league, the Association Football League of Chicago, began play.

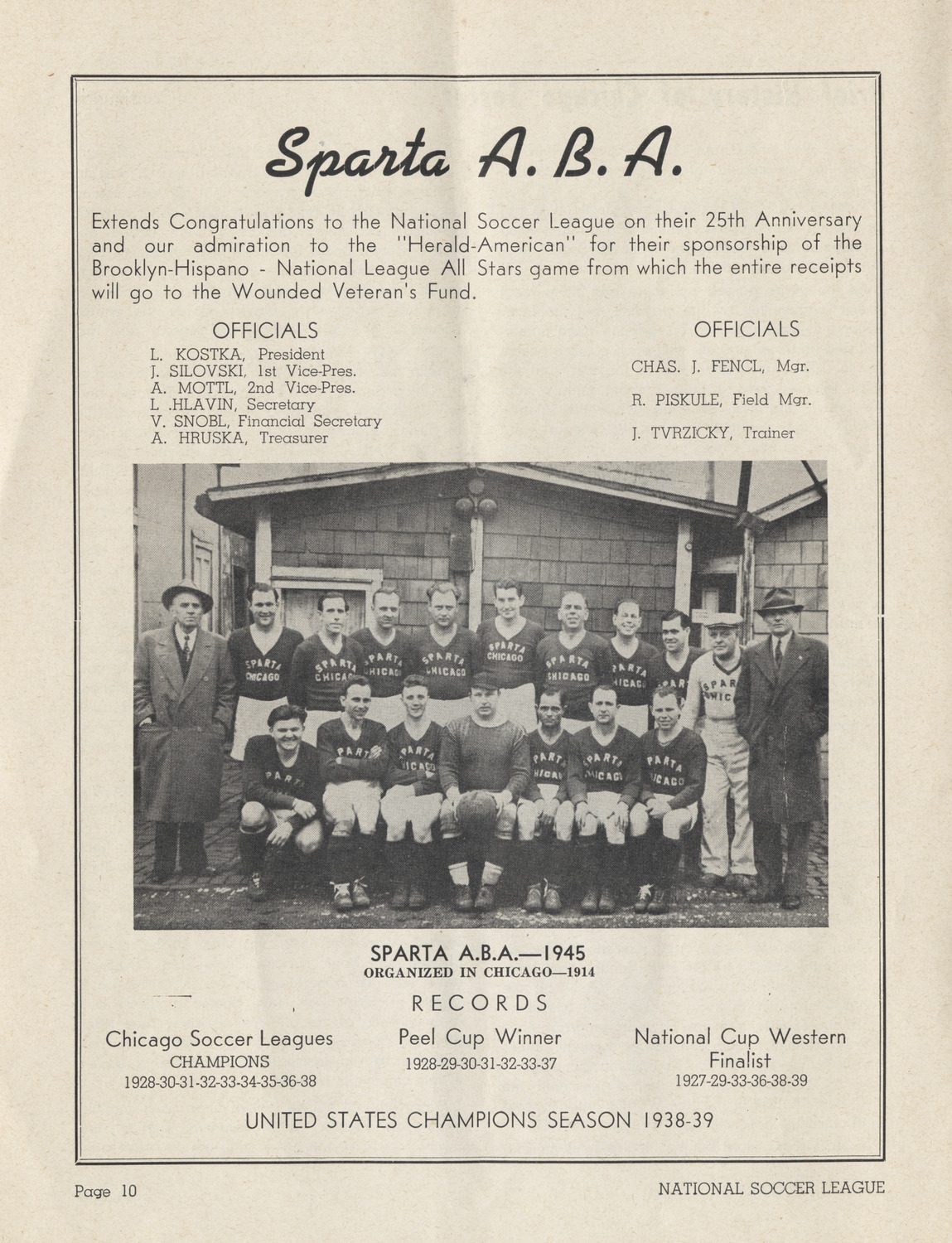

Sparta A.B.A. soccer team, a Czech organization, page from “25th Anniversary Program,” 1945. CHM, ICHi-037081

Just as organized soccer spread from England to the European continent and beyond, by 1912 soccer in Chicago parks had extended from English immigrant communities to other European ethnic groups. The formation of the International Soccer League (ISL) in 1920 brought organization and regulation to these teams. Twentieth-century amateur teams in Chicago, such as the Sparta, Schwaben, Vikings, Green-White, Eagles, Kickers, and Maroons, descended from soccer clubs that came to prominence in the ISL. Known to late-twentieth-century fans as the National Soccer League, the ISL claims the title of the nation’s oldest organized soccer league.

The Pullman girls’ soccer team, 1922. SDN-064029, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

In 1911, brothers Archibald and Alexander Paterson introduced soccer into two Chicago high schools, Englewood and Lane Technical. Other than a brief decline in 1936—when financial constraints allowed only two schools to field teams—high school soccer grew steadily more popular, and by the late twentieth century, soccer was drawing more participants than any other high school sport in the city.

Teen soccer team sponsored by the Rohingya Culture Center, Chicago, 2017. Courtesy of the Rohingya Culture Center.

Local universities also sponsored soccer. As early as 1910, the University of Chicago played the University of Illinois, and by 1928 the latter offered soccer as a varsity sport. Wheaton College has long been a preeminent collegiate soccer power, having fielded a varsity squad since 1935.

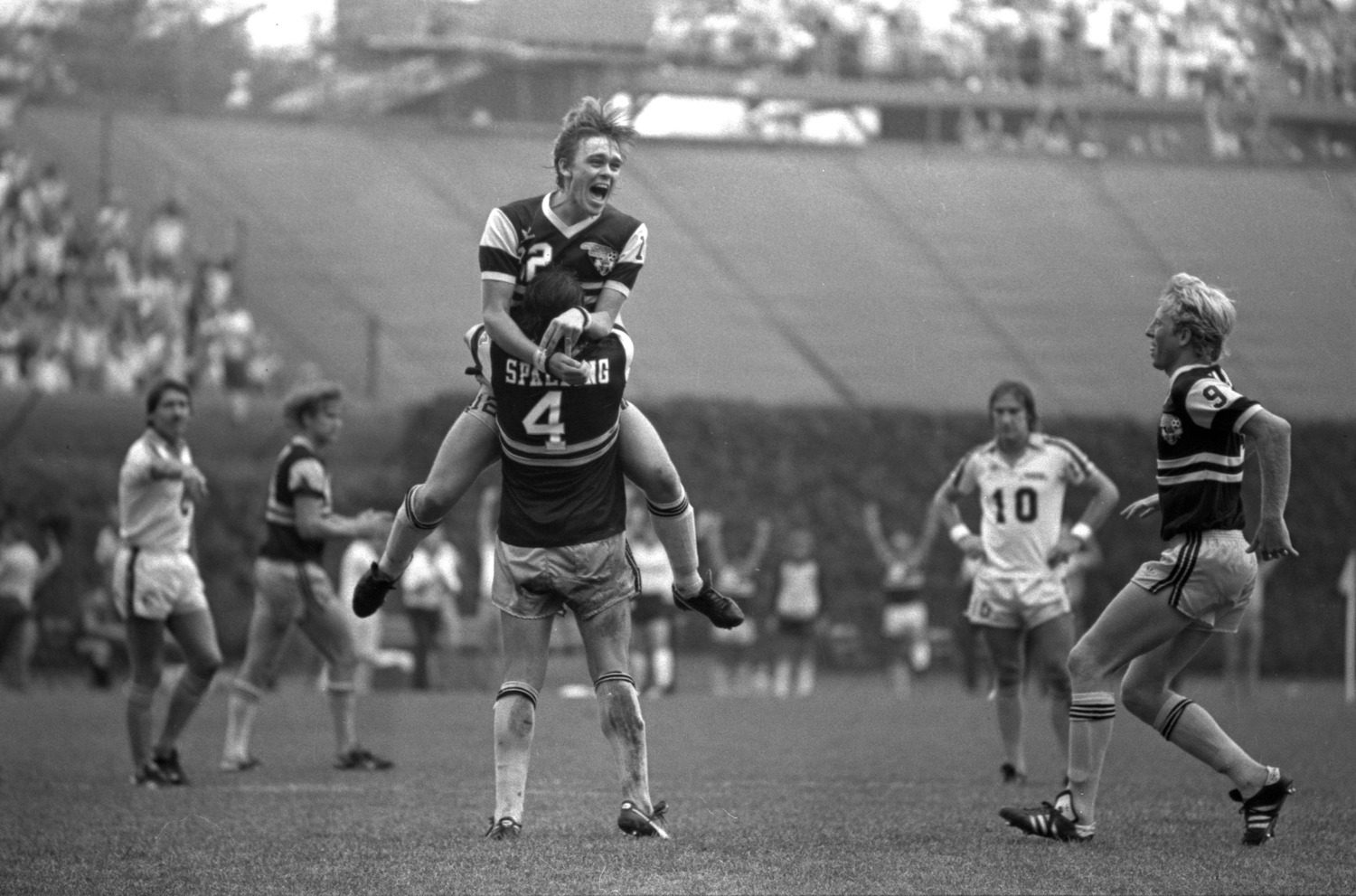

Professional Chicago soccer debuted in 1967, and the following year saw the formation of the North American Soccer League (NASL). The Chicago Sting captured two championship banners before the NASL folded in 1984.

Chicago Sting forward Karl-Heinz Granitza leaps into the arms of teammate Derek Spalding (4) after Spalding’s penalty kick tied the quarterfinal game vs. the Seattle Sounders at Wrigley Field, Chicago, August 30, 1981. The Sting won to advance to the NASL semifinals. ST-17500456-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

In the 1990s, the Chicago soccer scene grew in visibility. First, the United States Soccer Federation moved its headquarters in 1991 from Colorado Springs, Colorado, to two adjoining mansions in the historic Prairie Avenue District—the Kimball House, at 1801 S. Prairie Ave., and the house right next door at 1811 S. Prairie. [Ed. note: In September 2023, US Soccer announced that it will be moving Atlanta.] Then in 1994, Chicago was one of nine host cities for the FIFA World Cup, with the opening ceremonies and first match taking place at Soldier Field.

Chicago Fire general manager Peter Wilt (left) and Major League Soccer commissioner Douglas Logan announce the new Chicago MLS team at Gateway Park, near 600 N. DuSable Lake Shore Dr., Chicago, October 8, 1997. ST-20002829-0039, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Professional soccer returned to the city in 1998 with the Chicago Fire FC joining Major League Soccer. The Fire won the league championship and the Dewar (Open) Cup in its inaugural season.

From left: MLS players Bobby Boswell, Dwayne De Rosario, and Freddy Adu at the Sierra Mist MLS All-Star Game, Bridgeview Stadium (now SeatGeek Stadium), Bridgeview, Illinois, August 5, 2006. The MLS All-Stars beat Chelsea FC 1–0. STM-0440-0943, Jon Sall/Chicago Sun-Times.

In 1999, Chicago was one of eight US host cities for the FIFA Women’s World Cup. When the Women’s Professional Soccer league began play in 2009, the Chicago Red Stars were one of its inaugural teams. The Red Stars have since been part of the Women’s Premier Soccer League (WPSL), Women’s Premier Soccer League Elite (WPSL E), and, currently, the National Women’s Soccer League. They won the National Women’s Cup in 2012.

US forward Mia Hamm signs autographs at a team practice at Benedictine College (Benedictine University), 5700 College Rd., Lisle, Illinois, June 23, 1999. ST-70003772-0089, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

On the international level, Chicago clubs have played teams from London, Glasgow, Mexico City, Vienna, Prague, Budapest, Munich, Liverpool, Tel Aviv, Toronto, Uruguay, and Scotland. The memorable 1959 Pan-Am Games saw the US national team defeat Brazil and Mexico.

US midfielder John Harkes (6) dribbles the ball as defensive midfielder Thomas Dooley (5) looks on at a US-Germany game during the US Cup at Soldier Field, Chicago, June 13, 1993. The US lost 3-4. ST-80004406-0234, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The city has contributed players, managers, and coaches to most US Olympic and World Cup teams. In 1924, Chicagoan Peter J. Peel took the first US Olympic soccer team to Paris. Some of the greatest players of their time, such as Ben Govier and Sheldon Govier (Pullman), Julius Hjulian (Chicago Wonderbolts and keeper in the 1934 World Cup), Gil Heron (Chicago Corinthians and the first Black player in the Scottish First Division with Glasgow Celtic), Ed Murphy (Maroons, national team), Willy Roy (Hansa, national team, Sting), and Brian McBride (national team), honed their skills on Chicago soccer pitches.

Portrait of soccer player Ben Govier kicking a ball on a soccer field in Chicago, 1905. SDN-004081, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Although long ignored by mainstream press and media, soccer continues to be the most played sport in Chicago. Founded in 1916, the Illinois Soccer Commission coordinates more than 600 women’s and men’s teams, while more than 2,000 metropolitan Chicago youth teams compete in the Illinois Youth Soccer Association.

Additional Resources

- See more soccer-related photographs on CHM Images, such as the Chicago Sting in 1985, 1993 US Cup, and 1999 Women’s World Cup.

- Peruse the Abakanowicz Research Center catalog for soccer-related items.

At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE), Polish Chicagoans supported their homeland‘s participation despite colonizing empires, mainly Russia and Germany, resisting an independent Polish presence. Polish artists, musicians, and industrialists still displayed and performed for an international audience.

World’s Columbian Exposition Polish Day ribbon, Chicago, 1893. Collection of the Chicago History Museum, X.3005.2005

At the time, what had once been the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was consumed by the Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian Empires, so Polish people had no independent state beyond a few territories, including Congress Poland. Nevertheless, Polish Chicagoans met in spring 1893 to discuss how to help visitors from Polish lands and to organize a Polish Day for the fair. The major Polish American organizations at the time—the Polish Roman Catholic Union of America and the Polish National Alliance—supported these efforts.

Informal portrait of Ignace Jan Paderewski standing with a group in Chicago, 1922. DN-0074496, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Although overall Poland’s presence in the exhibits was slight, there were opportunities for several Poles to show their talents. On the second day of the fair, May 2, the renowned Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski performed with the fair’s orchestra. Then on August 4, 1893, Polish Chicagoan Maximilian Drzemala gave a lecture on Polish art, followed by an inauguration of the Polish art section at the Palace of Fine Arts. This was the first exhibition of Polish art in the United States and featured 122 paintings from 59 artists.

Piotr Kiołbassa, n.d. (Later published in Polska w Ameryka by Jan Drohojowski.)

The biggest impact on the fair came on Polish Day. On Saturday, October 7, 1893, thousands of Polish residents from all over the city took part in a procession to the site of the WCE. They gathered at Jackson Boulevard between Wood Street and Paulina Street. Piotr Kiołbassa served as the parade’s grand marshal. He had been elected city treasurer in 1891, the first Polish Chicagoan to serve in such a position. At 10 a.m., Kiołbassa led the parade of uniformed cavalrymen, carriages, bands, and floats toward Michigan Avenue. Many participants were members of Polish fraternal societies and community groups.

Chicago mayor Carter Harrison also participated, riding in a carriage behind Kiołbassa and Captain Joseph Nepieralski, an active participant in the 1830 uprising. The group marched toward Michigan Avenue and then down to the review stand at the Columbus statue. They proceeded to Twelfth Street and doubled back to Van Buren Street before finally going by train to Jackson Park.

The sixteen floats in the parade primarily depicted historical events. In his book American Warsaw, Dominic A. Pacyga writes that the idea behind all the floats was to “convinc[e] the city, and in turn, the world, of the righteousness of Poland’s call for the restoration of its independence” (p. 21). The last float in the parade was from St. Casimir’s Parish and was titled “The Resurrection of Poland.” It displayed a broken prison gate with a female figure representing Poland emerging from it with several “dead” Russian, Austrian, and Prussian soldiers lying around.

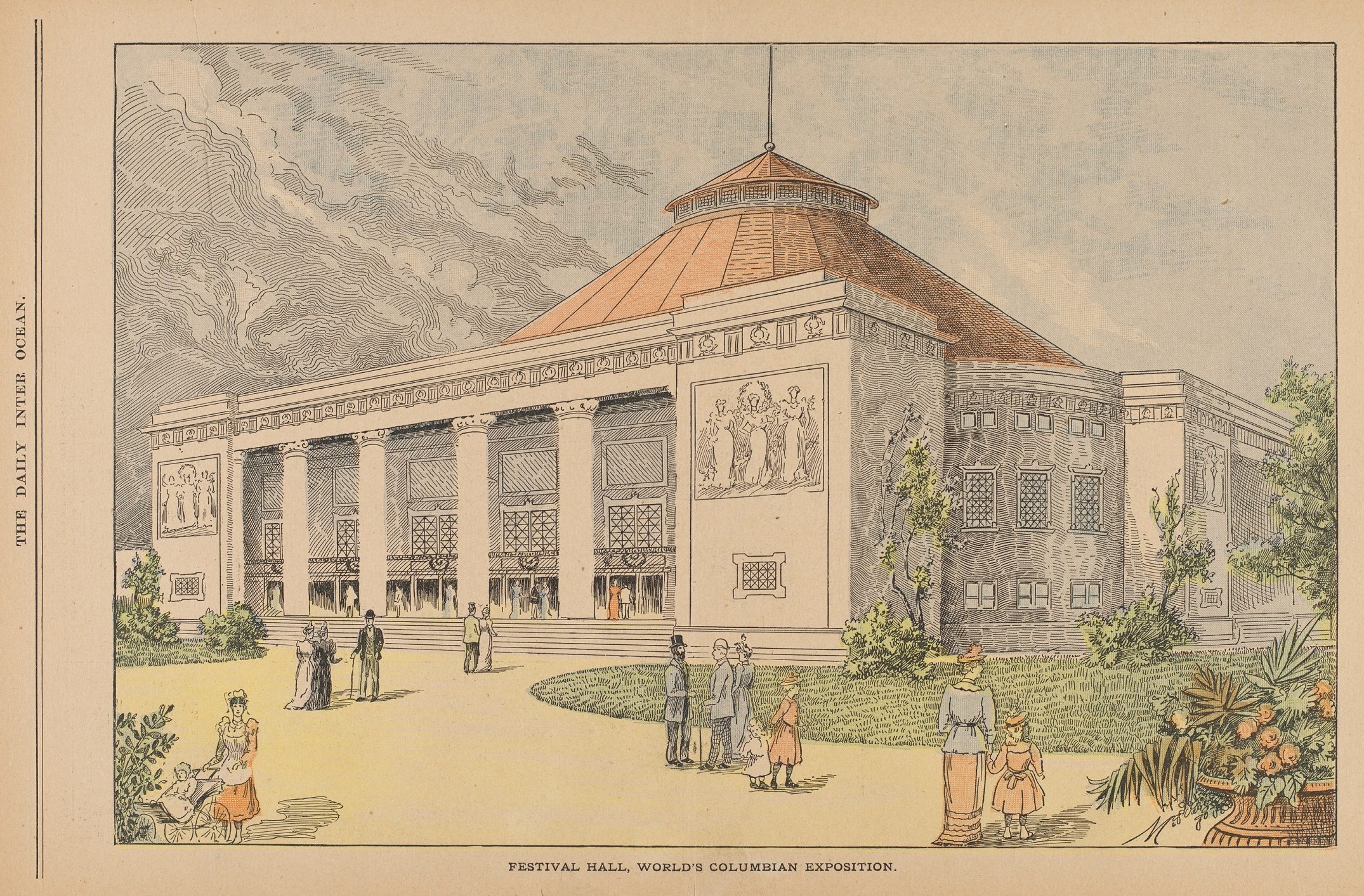

Color illustration titled “Festival Hall, World’s Columbian Exposition,” Chicago, 1893. Published in The Inter Ocean Illustrated Supplement. CHM, ICHi-089488

The parade ended at Festival Hall with remarks from Polish Day Central Committee president S. Słominski, Judge Michael A. LaBuy, and Mayor Harrison. Between eight and ten thousand people attended the ceremony. October 7 was one of the most attended days of the entire fair, with various reports claiming twenty-five to fifty thousand Polish Americans in attendance.

See the Polish Day ribbon, as well as items from the 1933-34 A Century of Progress world’s fair, in our Back Home: Polish Chicago exhibition.

Content warning: This blog post contains text and images about violence and sexual assault that may be traumatizing to some audiences. Reader discretion is advised.

Every July 13 marks a grim anniversary in Chicago’s history. On an otherwise normal Wednesday night, Jeffery Manor, in South Deering on the Far South Side witnessed what would later come to be called the “crime of the century.” In a townhome on 100th Street, mass murderer Richard Speck would torture, sexually assault, and ultimately murder eight nurses in one of the grimmest crimes in US history.

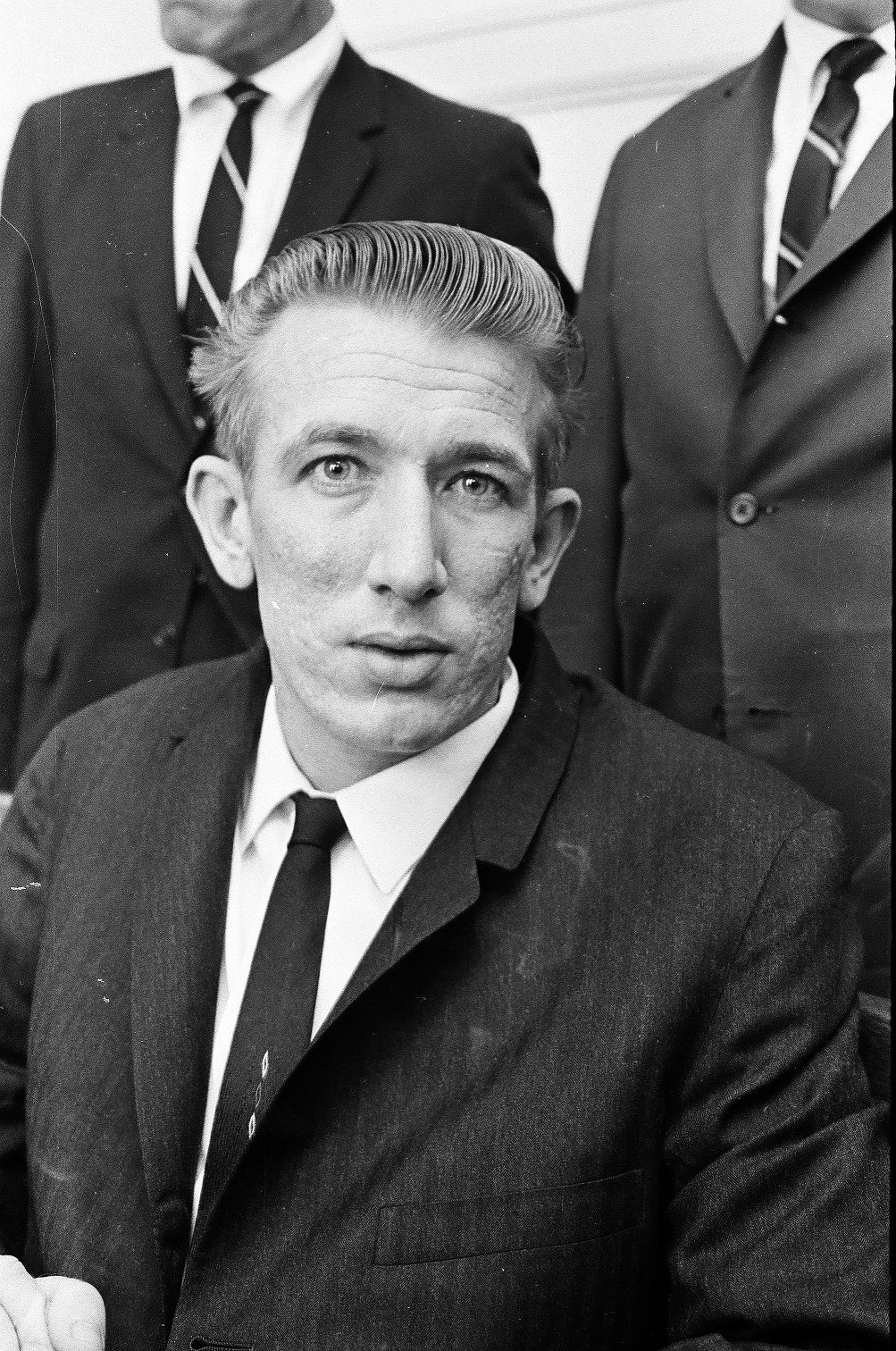

Murder suspect Richard Speck during his criminal court hearing at 2650 S. California Ave., Chicago, August 18, 1966. ST-19110229-0015, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Richard Benjamin Speck was born on December 6, 1941, in the village of Kirkwood, Illinois, about 200 miles west of Chicago. The seventh of eight children, Speck was born into a tumultuous low-income family, and he spent most of his youth growing up in the Dallas, Texas, suburbs where he regularly had run-ins with law enforcement due to his excessive drinking and penchant for public disturbances. Speck received his first major prison sentence in July 1963 at the age 21 when he was convicted of forging a signature on a stolen check and for the robbery of a grocery store. Originally due to serve three years, he was paroled after 16 months only to return to his cell a week later on charges of aggravated assault and a parole violation.

Speck would continue to add lines to his rap sheet in Texas before moving to Chicago to live with his sister in 1966. It was there that his brother-in-law found him work as an apprentice seaman. As was standard practice at the time, when he didn’t have work, Speck would check in at the National Maritime Union hiring hall, in the hopes of receiving an assignment to a vessel. It was a few days with no luck in securing work, on Wednesday, July 13, that Speck began his murderous rampage by sexually assaulting and robbing Ella Mae Hooper, a local woman he met at a bar.

The townhomes at 2319 E. 100th St., Chicago, July 22, 1966. ST-10000417-0010, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Later that night, around 11 p.m., the then 24-year-old Speck broke into a townhome that served as shared housing for foreign and local nursing students who worked at the local South Chicago Community Hospital. Here, over the course of a few hours he would be responsible for the murder of the eight women who were all inside the premises when Speck broke in. One woman, Corazon Amurao, escaped the death that met her housemates by hiding under the bed until the early morning. It took two days for authorities to apprehend Speck. Chicago Police received a lucky break and arrested Speck when a physician from the Cook County Hospital alerted them that a man they were treating following a failed suicide attempt was believed to be him. The physician had noticed a tattoo on the man’s forearm that read “born to raise hell,” and they recalled a newspaper description of the suspect that mentioned his ink.

Corazon Amurao, witness in the Richard Speck trial, entering the Peoria County Courthouse with her mother, 324 Main St., Peoria, Illinois. ST-19110250-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

After being deemed competent enough to stand trial by a panel of medical professionals, Speck’s trial began in early April 1967 at the Peoria County Courthouse. The evidence against him was damning. In addition to the eyewitness testimony of Amurao, the lone survivor, fingerprints recovered at the scene matched Speck’s. The high-profile trial lasted less than two weeks, and after deliberating for less than an hour, on April 15, the jury found Speck guilty and recommended that he be served the death penalty. In June, a judge upheld the jury’s recommendation and sentenced Speck to death by electric chair. When the media referenced the trial, they often referred to Speck as a “mass murderer.” While today the term is part of everyday vernacular, referring to someone as a mass murderer in the 1960s was a new phenomenon.

Onlookers watch as police remove eight student nurses slain at 2319 E. 100th St., Chicago, July 14, 1966. ST-17500750-E1, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

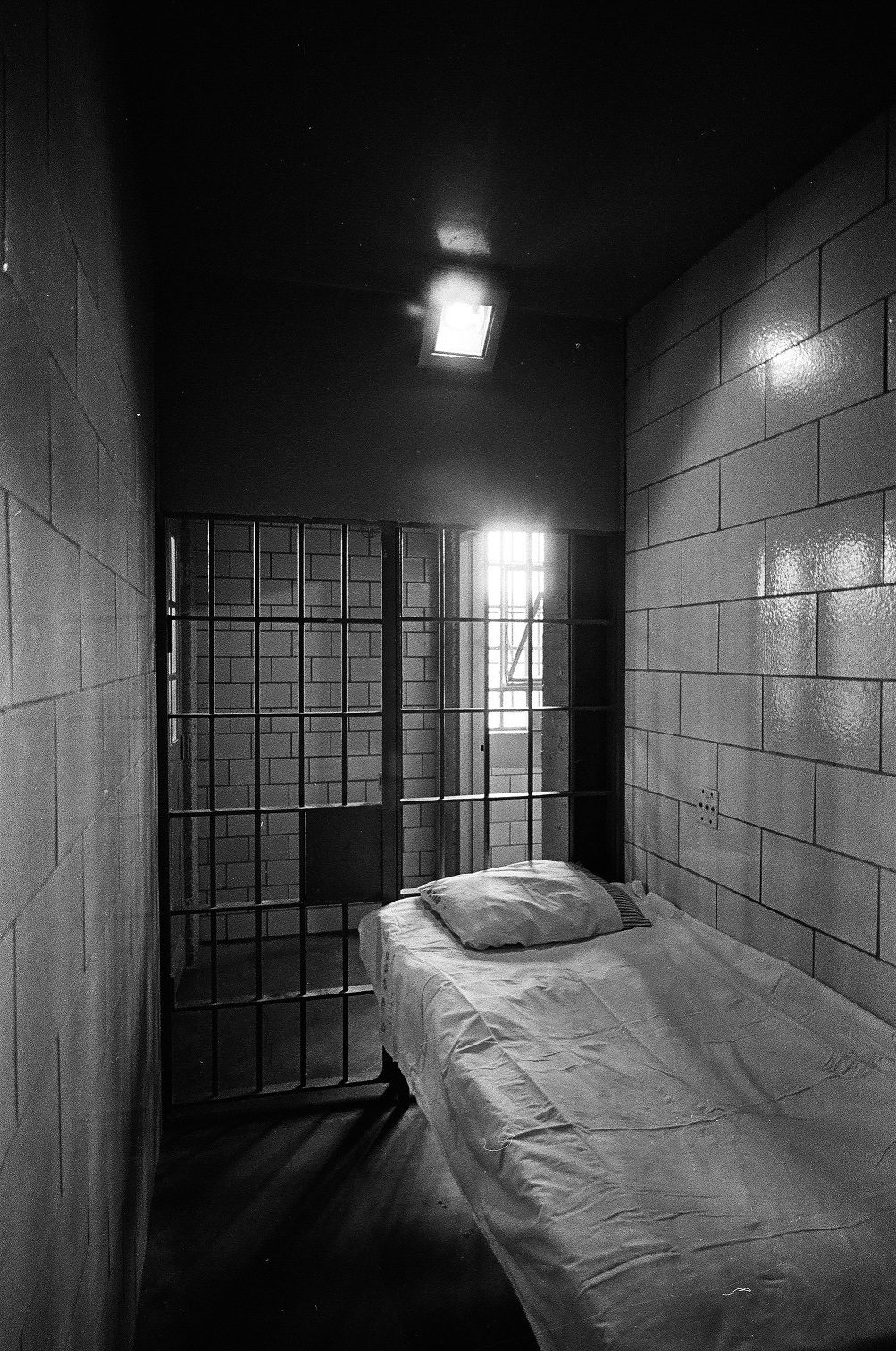

On June 29, 1972, the Supreme Court ruled in the case Furman v. Georgia, thereby declaring the death penalty unconstitutional, which forced a resentencing for Speck. He received his new sentence in November of that year, ordered to serve from 400 to 1,200 years in prison through eight consecutive sentences. It would later be reduced to a sentence of 100 to 300 years. He would serve his sentence at the Stateville Correctional Center in Crest Hill, Illinois. While imprisoned, Speck unsuccessfully petitioned to be paroled no less than seven times. He died due to what is largely believed to have been a heart attack on December 5, 1991, in a hospital in the nearby town of Joliet, one day before what would have been his fiftieth birthday. He was cremated and his ashes were scattered in an undisclosed area.

The gruesomeness of Speck’s murders captured the fear and imagination of an entire generation, and has been retold in countless films, television episodes, and books. In the decades following the Speck murders, often referred to now as the Chicago Massacre, he only granted one interview to the media when he spoke to a Chicago Tribune columnist in 1978. In that interview, he admitted to being under the effects of alcohol and drugs, and further claimed to have had an accomplice, whom Speck murdered in fear that he would turn him in. No such proof of an accomplice has ever been found.

The names of Speck’s victims were Gloria Davy, Patricia Matusek, Nina Jo Schmale, Pamela Wilkening, Suzanne Farris, Mary Ann Jordan, Merlita Gargullo, and Valentina Pasion. All of them were in their early twenties and were robbed of their promising futures as caregivers and medical professionals. Pasion and Gargullo were both exchange students from the Phillipines. Their bodies were repatriated after a mass was held in their honor in Chicago.

Cell at the Stateville Correctional Center that housed Richard Speck, Crest Hill, Illinois, May 1, 1967. ST-19110222-0044, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Additional Resource

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s 1967 interview with Dr. Marvin Ziporyn, Speck’s psychiatrist. (Note: Dr. Ziporyn did not testify for the defense or the prosecution, as both sides were troubled to learn before the trial that he was writing a book about Speck for financial gain.)

CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman writes about CHM’s collection of souvenirs contemporary to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and how they inform the stories we tell today.

Souvenir pins from the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-066817. Souvenir silver spoons featuring the likeness of Bertha Honoré Palmer from the World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893. CHM, ICHi-053270.

The word “souvenir” is the French verb “to remember,” and by extension, souvenirs as objects are meant to embody people’s experiences, stories, and memories. In the Chicago History Museum’s collection of 23 million objects, a robust number of items are related to Chicago’s two world’s fairs: the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE) and 1933–34 A Century of Progress International Exposition. Items typically classified as “souvenirs” of the fair–such as postcards, photographs, spoons, pins, and ribbons–are so well represented in CHM’s holdings, we no longer accept donations of most WCE ephemera.

The questions we face now encompass the context of all these souvenirs, such as:

- For whom were they made, what do they represent, and what memories or remembrances are they meant to ignite?

- Can we use them to tell a fuller story beyond the personal memories they were intended to evoke?

- What are the deeper, harder histories that were not previously centered in their interpretation or in other recollections and retellings of the fairs?

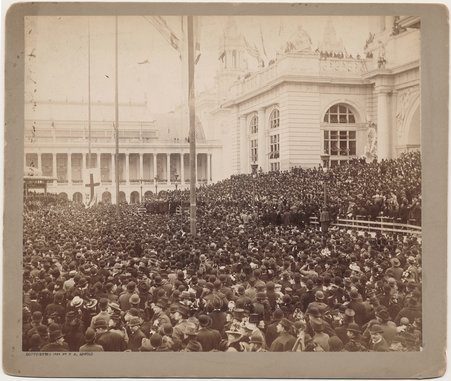

Opening day of the World’s Columbian Exposition, May 1, 1893. CHM, ICHi-059979.

Open from May 1 through October 30, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition brought more than 27 million visitors to Chicago. Souvenirs such as those above were made and bought as personal keepsakes at a never-before-seen scale. Souvenir manufacturing and purchasing exploded in the nineteenth century as industrial advancements allowed for mass production. Items such as collectable spoons had gained popularity with wealthy and upper middle-class Europeans and Americans on grand tours in the mid-nineteenth century. By the 1890s, as they became more accessible and affordable, a broader audience had financial access to commemorative items. Beyond just physical tokens, souvenirs served as an access point to a marking of social class previously reserved for the wealthy. They also held individual symbolic meaning and memory for their purchasers, resulting in their abundant presence today.

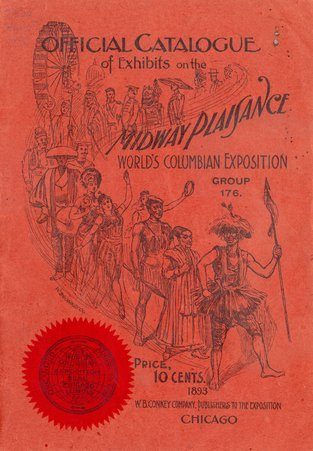

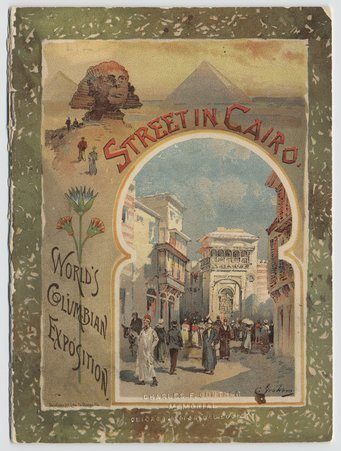

Cover of the Official Catalogue of Exhibits on the Midway Plaisance, 1893. CHM, ICHi-065727.

In the case of the WCE, they also form an important part of our historical memory and speak to the process of building a collection to represent a city’s history drawing on a very nineteenth-century colonial notion of collecting not just objects, ideas, and memories but identities and people.

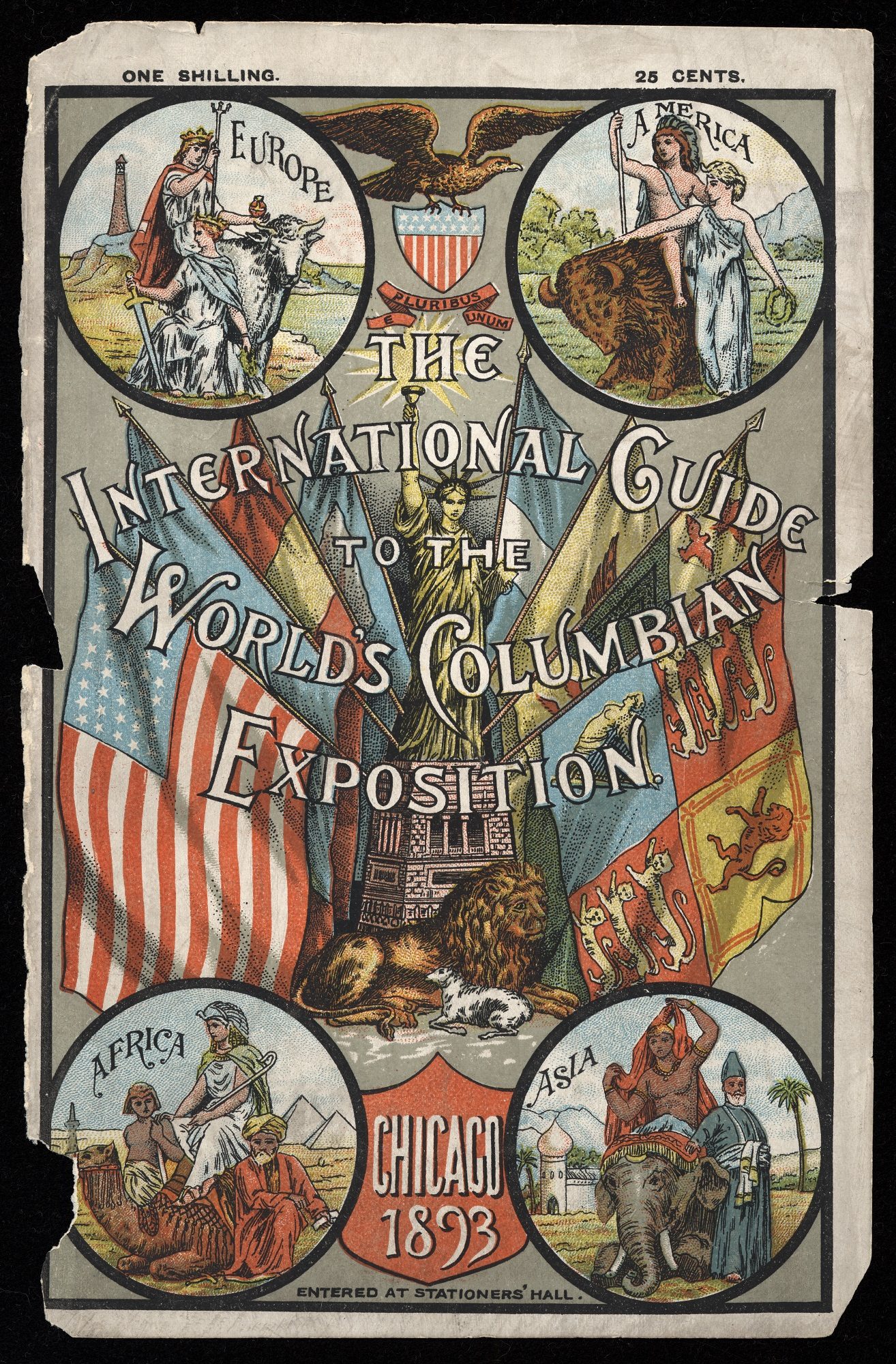

Front cover of The International Guide to the World’s Columbian Exposition, published by the International Guide Syndicate, 1892. CHM, ICHi-040435

World’s fairs―broadly speaking―created the canvas upon which participating nations could project a filtered, essentialized view of themselves (and others) on a global platform. The 1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in London set the tone for Victorian-era framing of an empire on display. This model proved useful to both the continuation of global exhibitions but also the development of fields of study such as anthropology and museology. The process of classifying and showcasing identities through a colonial lens has translated into the complex legacy many museums face. Collections, including those surrounding world’s fairs, center privileged experiences with many voices and experiences represented through racialized prejudice as a view of the “other” and lack equitable representation of diverse perspectives.

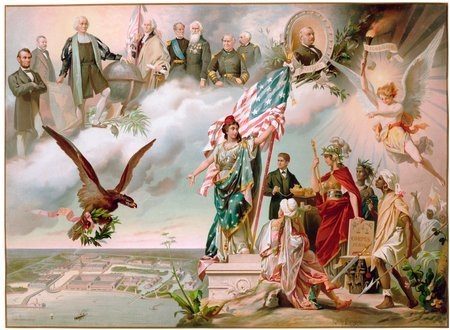

Allegorical lithograph of Christopher Columbus with US presidents and the 1893 WCE by Rodolfo Morgari, CHM, ICHi-025233

The WCE aimed to position Chicago as a sophisticated global center and shift away from its reputation as an industrially polluted, dangerous city at the edge of the western frontier. Many US cities experienced a sense of fragmentation after the Civil War, compounded by massive industrial growth, class divides, and racial tensions. In Chicago, these pressures were amalgamated in the wake of the Great Fire of 1871, and it looked to rebrand itself as a city of future promise. This opportunity came with the successful advocacy to host the 1893 world’s fair commemorating the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus’s arrival in North America. This positioning asserted racial and intellectual dominance of Euro-Americans over Indigenous peoples as manifested through an idealized narrative of Columbus’s role in establishing a religiously motivated presence in the future United States of America.

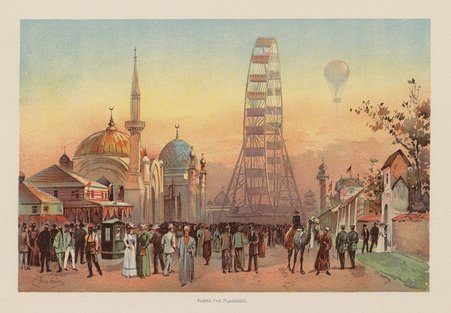

Color illustration by Charles Graham titled “Along the Plaisance,” World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-052343.

The construction of the WCE was a reaction to and an embodiment of this cultural supremacy through its construction as a duality of identity between the White City, which symbolized a utopian vision of the United States’ future, and the Midway Plaisance, which represented anthropological foundations. Western perspectives of a certain global racial stratification informed divisions between exhibitors, with selected nations submitting plans for national pavilions while others were relegated to the more carnivalesque atmosphere of the Midway—and some notably without representation at all. Ethnological displays romanticized, exoticized, primitivized, and objectified those who represented the living embodiment of their cultural identity for the enthusiastic, and at times cruel, audience.

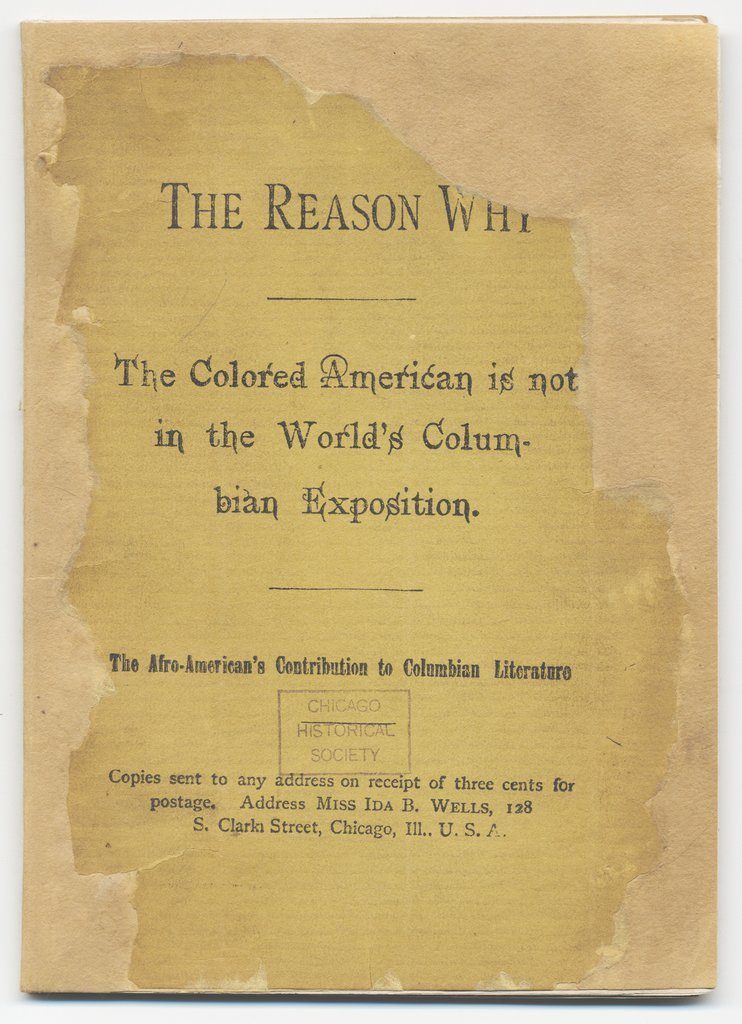

Front cover of The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition by Ida B. Wells, 1893. CHM, ICHi-040399.

This division did not go without commentary at the time. Powerful examples of dissenting voices and personal advocacy persist, though captured in less represented ephemera. For example, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Frederick Douglass published a pamphlet protesting the lack of African American representation, with Wells referring to the White City as the “white sepulcher.” Simon Pokagon gave a cutting critique of Indigenous displacement through his speech, and later publication, for Chicago Day at the fair, questioning why they would “. . . celebrate our own funeral, the discovery of America.” These are just two examples of the wide gap of experiences of the fair based on race and point to the possibilities of further counternarratives yet to be unearthed.

Cover of pamphlet titled “Street in Cairo,” 1893, CHM, ICHi-038001_a. Group of men near the Turkish village at the Midway Plaisance, 1893. CHM, ICHi-025117.

These collections and interpretations around the WCE bridge larger questions of how we address representational disparities in a broader way. The significance of our collections is not just in the number of items held but the stories they tell. An overabundance that represents a particular lens of the WCE warrants an important rebalancing in the items we collect, the space we make, and the perspectives we share in addressing the legacy of the WCE and how it has shaped Chicago—and global—history.

Additional Resources

- Listen to historian Robert Rydell discuss his book All the World’s a Fair: Visions of Empire at American International Expositions, 1876-1916 with Studs Terkel

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago overview entry on the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and entry on World’s Columbian Exposition

- Learn more about CHM’s collecting scope

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry about Ida B. Wells-Barnett at the 1893 world’s fair

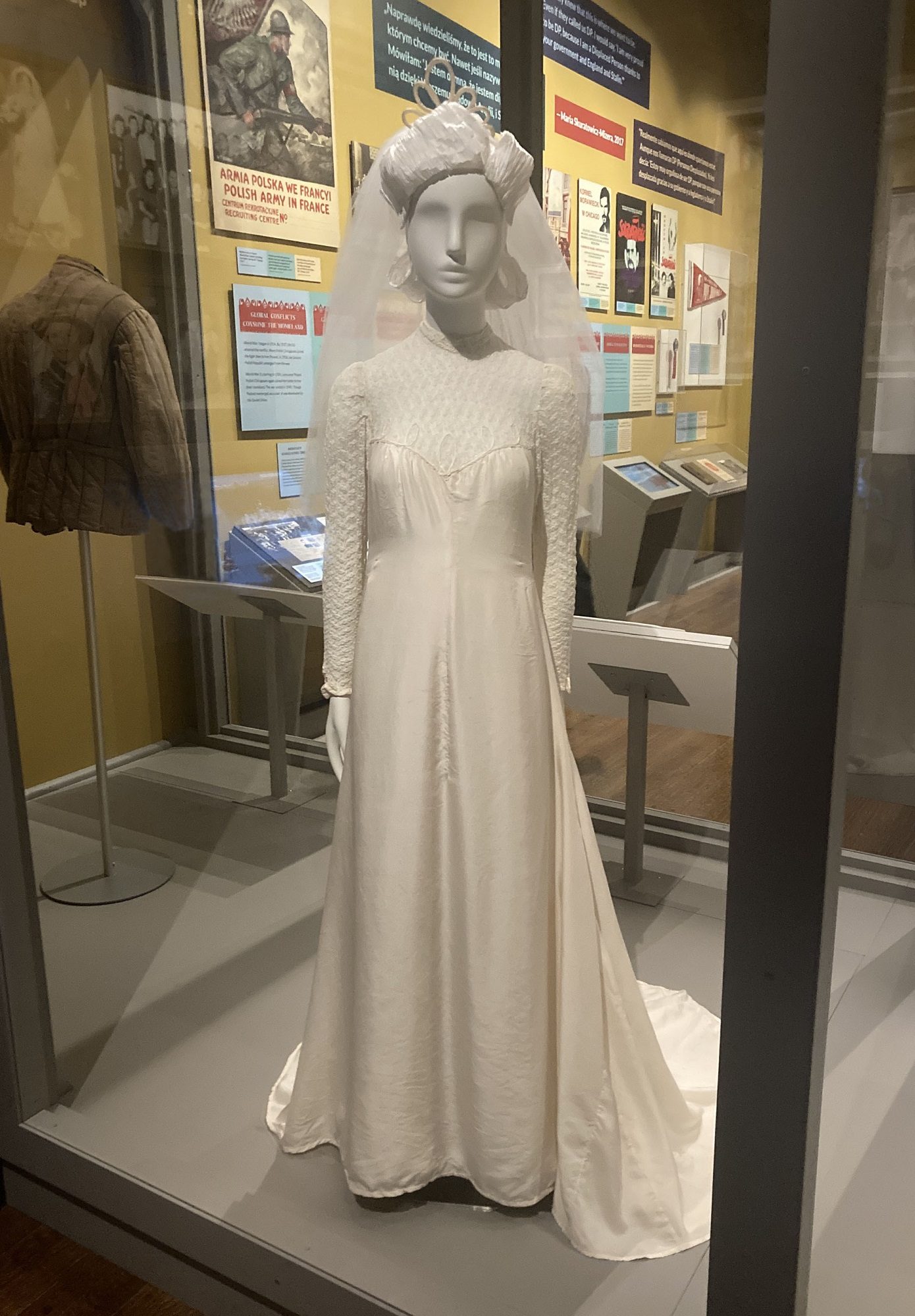

In this blog post, mount maker Michael Hall writes about preparing a wedding gown with a poignant backstory for display in Back Home: Polish Chicago.

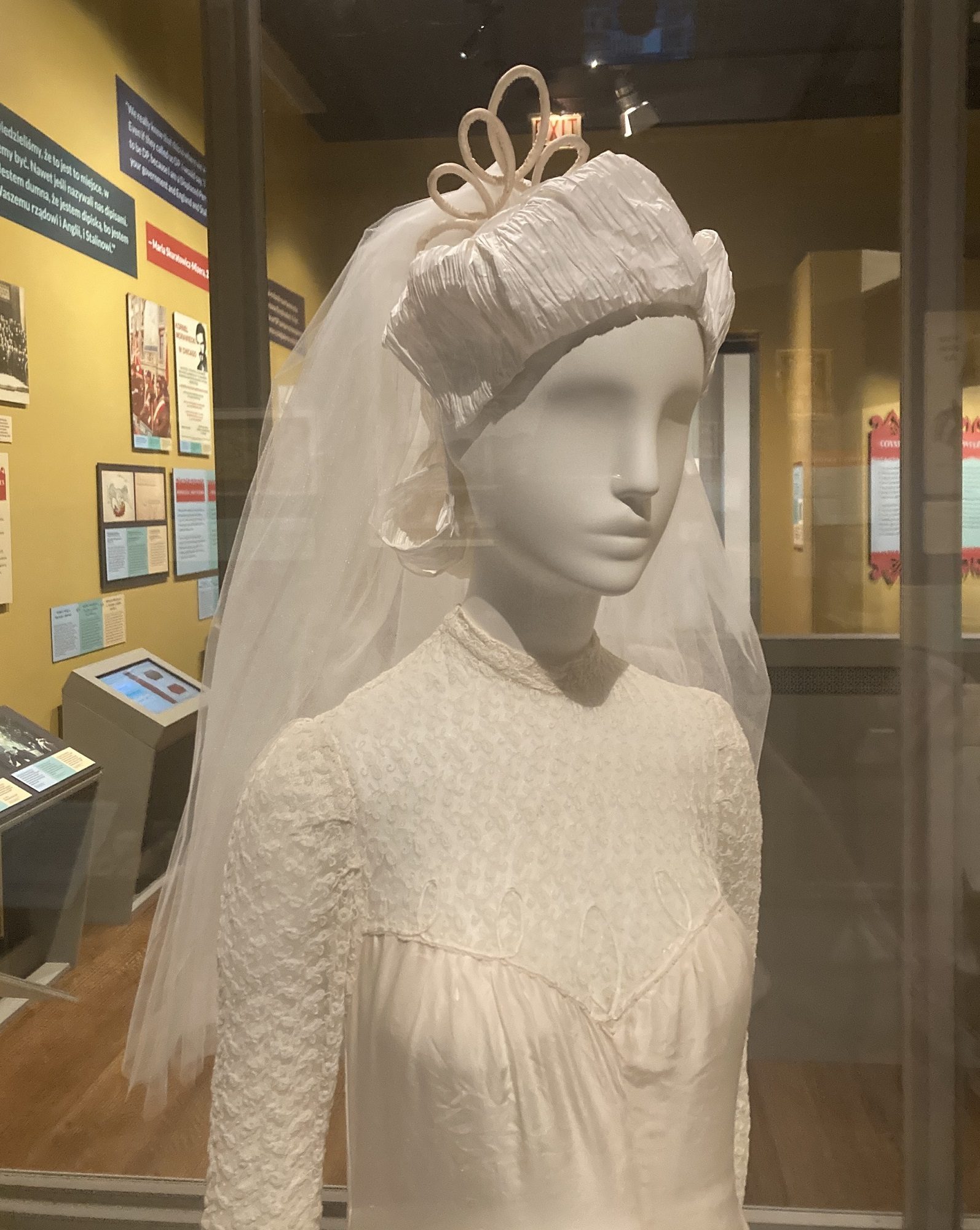

Front view of Jane Wyrwa’s wedding dress and headpiece, Göppingen, Germany, 1947. Courtesy of Eve Wyrwa-Miller. All photographs by CHM staff.

In 1944, Wiesława “Jane” Lippert, originally from Łodz, Poland, and Richard Wyrwa, originally from Lwów, Poland, met at the Nazi forced labor camp and factory in Markranstädt, Germany. There, Richard helped Jane with her assigned job of machining airplane parts, as she had never worked with her hands before. After World War II ended, they lived at the Displaced Persons camp in Göppingen, Germany, where Richard worked as a regional supply officer. They married there in 1947. A local seamstress made Jane’s wedding dress from the silk of a surplus World War II parachute bought from the US military. The dress features a yoked bodice, net lace long sleeves, and a twill weave fabric lining.

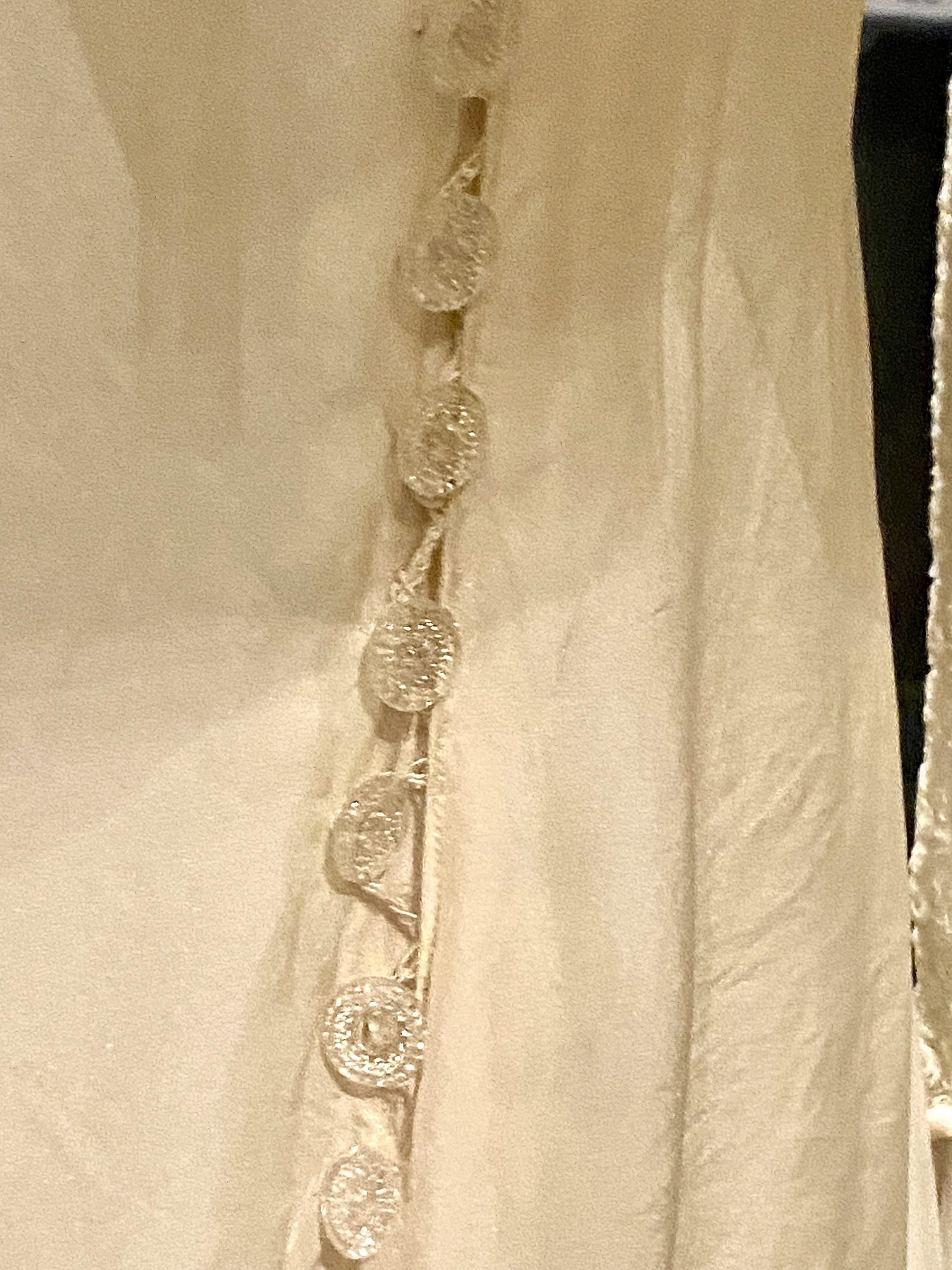

Close-up of loop detail on the bust, which is mimicked in the headpiece.

The gown is bias cut and pieced together with net lace and plastic daisy buttons down the back.

Back view of the gown, showing a short train.

Close-up of the lace detail on a sleeve.

The plastic daisy buttons running down the back.

One of the first things you’ll notice about the dress is just how petite it is. To achieve the mount for this dress, Michael had to get a little creative, using a mix of mediums so the dress could be supported. Additionally, the length of the dress was shorter than the prefabricated mannequin so a modified base from the high hip down was needed to accommodate it.

Michael Hall working on the dress mount.

Starting with taking the measurements of the dress, he padded out a petite sized mannequin with polyester fiberfill to a size just smaller than the actual dress size. Then an outer layer of Fosshape, a sewable felt-like heat-activated thermoplastic textile, was added to cover the padding to create a hardened shell or “new skin” upon which the dress could sit.

Hall adds a layer of Fosshape to the left shoulder.

Building the hips out was an additional challenge due to the modified base that did not have the full length of the hips to support the dress. The solution was padding the hips out using the original leg base, adding Fosshape on top and hardening, then removing the legs and replacing them with the modified base. Michael was careful to line the Fosshape seams up to the dress seams to minimize the visibility of the mount, which was especially tricky around the net lace neckline. Once the Fosshape layer was complete, a couple of nylon petticoats were fitted just before the final dressing to give some volume to the skirt.

Portrait-style photograph showing the bust details and the headpiece, which sits atop a paper wig.

Jane had created her own headpiece and veil, which was reproduced for the exhibition. The headpiece on the mannequin consists of silk wrapped on wired cording with some new netting to simulate a veil with loose hand tacking wrapped around a couple areas but not through the piece. It was then secured to the styled paper wig using bug pins, which are very fine and sharp pins that minimize any damage to the piece.

You can see the wedding dress and learn more about the Wywra family’s story in Back Home: Polish Chicago.

June 28, 2023, marks the start of Eid al-Adha, a major Islamic holiday. In this blog post, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman highlights a past moment of celebration and the communities that brought it together.

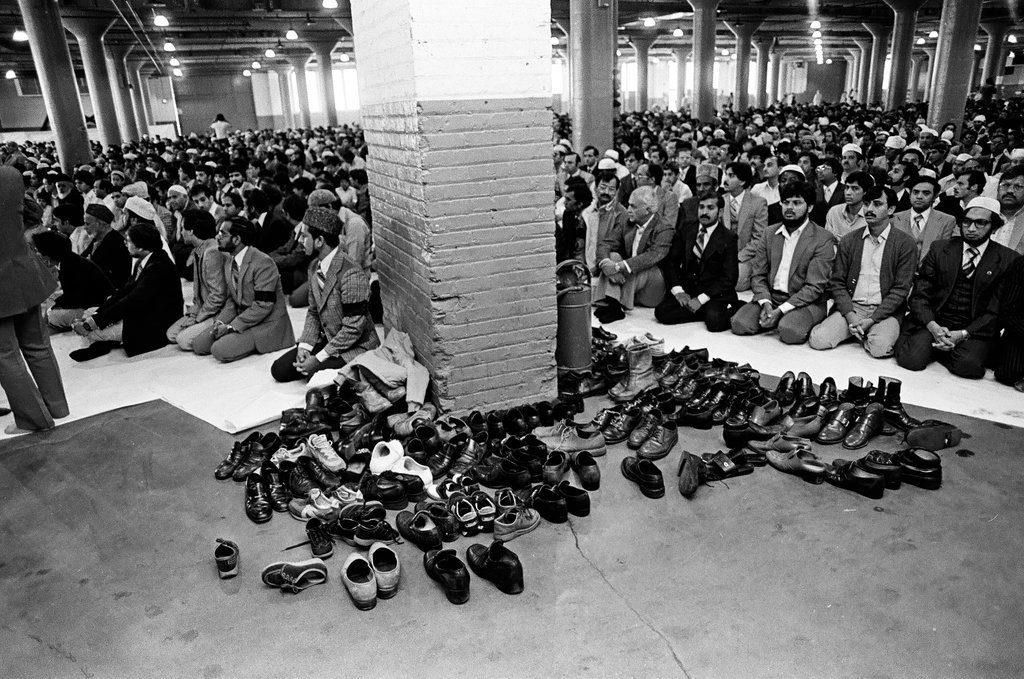

Eid Al-Adha gathering at the International Amphitheatre, Chicago, 1982. ST-30002684-0053, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Known as the Feast of Sacrifice, Eid al-Adha is one of Islam’s two main holidays and commemorates the Quranic story of Ibrahim’s (Abraham’s) willingness to sacrifice his son Ismail (Ishmael). In the story, Allah honors Ibrahim’s intention and provides a substitute sacrificial ram through the Angel Jibreel (Gabriel) in Ismail’s place. Consequently, the holiday is commemorated through qurbani (the sacrifice) of an animal, usually a goat, sheep, cow, or camel. Its meat is eaten and shared with others in the community and those with less financial means.

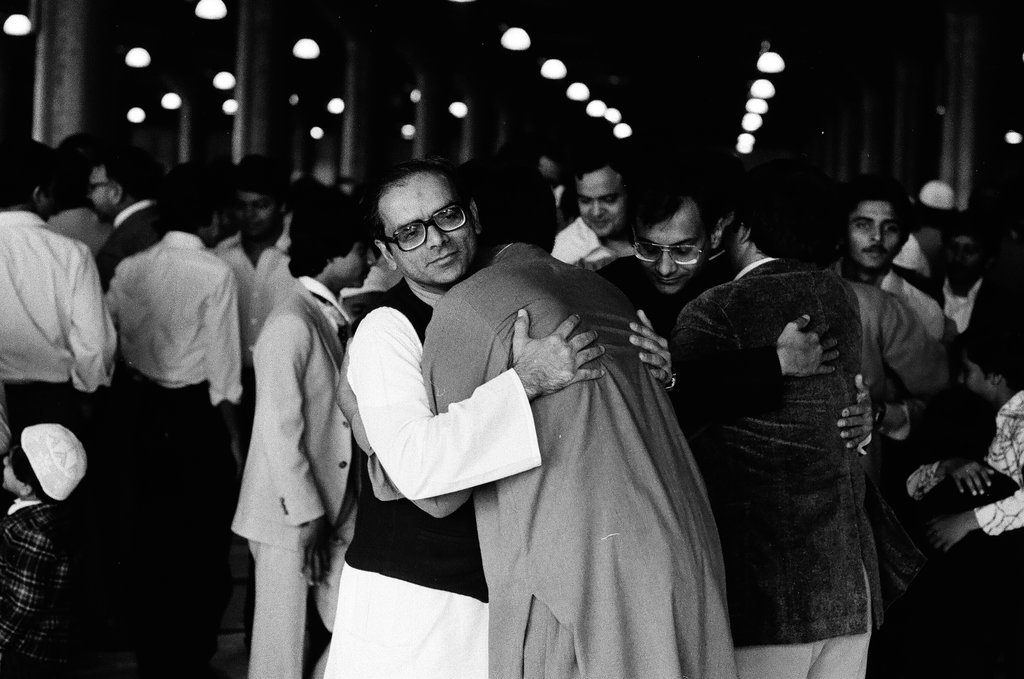

Men hugging at the Eid al-Adha gathering at the International Amphitheatre, 1982. ST-30002684-0026, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Since the holiday is based on lunar sightings, the Gregorian calendar date of Eid al-Adha changes each year, but it takes place on the tenth day of Dhu al-Hijja, the twelfth and final month in the Islamic calendar. Hajj, or pilgrimage, is one of five pillars of Islam. During this month, Muslims from around the world gather in and around the holy city of Mecca in Saudi Arabia. Eid takes place temporally during this important time of year while pilgrims are in Saudi Arabia and is celebrated globally within the Muslim ummah (global community).

Two women entering the International Amphitheatre for Eid al-Adha gathering, 1982, ST-30002684-0036, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

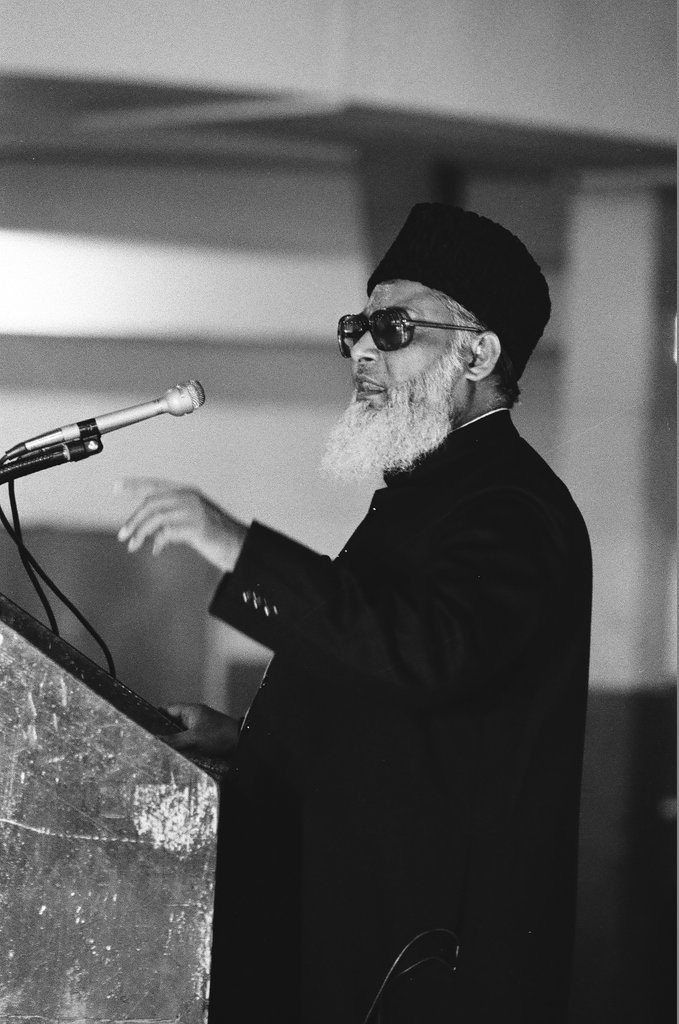

A central part of celebrating Eid is eating together and attending communal prayers. This series of photographs comes from an Eid al-Adha gathering of the greater Chicago Muslim community on September 28, 1982, at the International Amphitheatre at 4220 South Halsted Street. Ten thousand people were expected to be in attendance. A contemporaneous article from the Chicago Defender noted that Dr. Israr Ahmed (1932–2010), a Pakistani Sunni Islamic leader and theologian led the congregational prayer and gave the sermon that day.

Eid al-Adha gathering at the International Amphitheatre, 1982, ST-30002684-0048, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Dr. Ahmed was born in Hisar, East Punjab, attended medical school in Lahore, and began practicing medicine shortly thereafter. In 1971, he left his medical career to work full-time as a religious leader and, in 1975, founded Tanzeem-e-Islami. He became a household name in Pakistan through his numerous television programs and his prolific writing on Islamic thought and belief. His thought leadership was well known beyond Pakistan’s borders through the South Asian diaspora.

Dr. Israr Ahmed speaking at the Eid al-Adha celebration, 1982. ST-30002684-0018, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

At the time of his sermon in 1982, Chicago was growing to become one of the largest concentrations of South Asian migrants in the country. Migration to Chicago began following the partitioning of British India in 1947 and accelerated in the mid 1960s, with the communities’ presence growing in the subsequent decades. For example, by 2000, more than 18,000 Pakistanis were counted in the federal census in the metropolitan Chicago area, but community estimates were considerably higher (80,000–100,000).

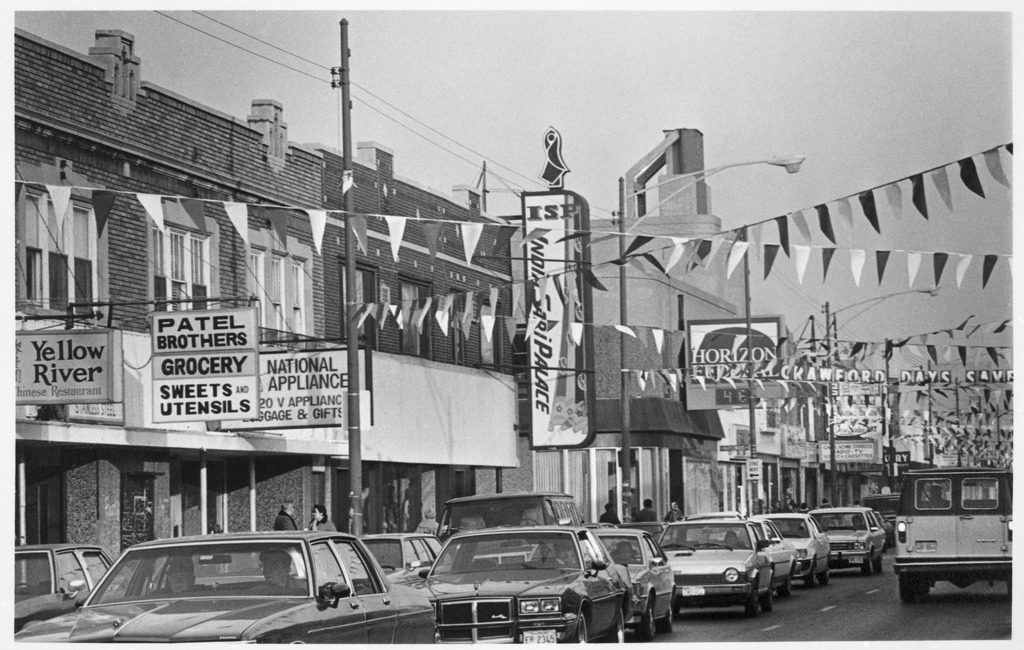

The street scene on Devon Avenue near Maplewood Avenue, Chicago, November 1984. CHM, ICHi-026078; Mukul Roy, photographer

While the diaspora today is dispersed among many suburban communities surrounding Chicago proper (such as Naperville and Bolingbrook), cultural and commercial memory has centered in and around Devon Avenue in the West Ridge neighborhood.

Adapted storefronts along Devon Avenue and Western Avenue, 2023. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman.

Host to numerous South Asian businesses, places of worship, and restaurants, since the 1970s Devon Avenue has become home to one of the largest South Asian communities in the country, indicated by nods such as the honorary naming of sections of Devon for significant figures, including Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. Other community markers acknowledge the complex and diverse legacy of the many communities that have made their home near Devon, including Indian, Bangladeshi, Assyrian, Russian, Jewish, and English migrants and settlers.

Additional Resources

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entries on Pakistanis, Indians, and Bangladeshis

- Learn more about the Museum’s oral history project American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago

- See materials about Devon Avenue in the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit

June 26, 2023, marks the 130th anniversary of Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld pardoning three men who were wrongfully imprisoned for their connections to the Haymarket affair. In this blog post, CHM director of exhibitions Paul Durica discusses Altgeld, the incident at Haymarket, and its aftermath.

Sleep softly . . . eagle forgotten . . . under the stone.

Time has its way with you there, and the clay has its own.

“We have buried him now,” thought your foes, and in secret rejoiced.

They made a brave show of their mourning, their hatred unvoiced.

They had snarled at you, barked at you, foamed at you day after day,

Now you were ended. They praised you . . . and laid you away.

So begins “The Eagle that is Forgotten,” a poem by Vachel Lindsay about his “next-door neighbor” in Springfield, Illinois, from 1893–97. That neighbor, the forgotten eagle, was John Peter Altgeld (1847–1902)—the first Chicagoan to become governor of Illinois.

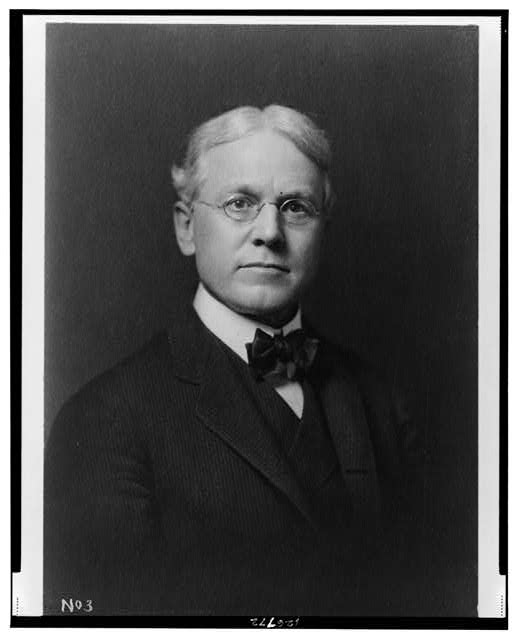

Portrait of John Peter Altgeld, c. 1893. CHM, ICHi-009404; Schloss, photographer

Born in the Duchy of Nassau, now the German states of Rhineland-Palatinate and Hesse, Altgeld was a lawyer and dabbler in real estate. He became a judge in 1887 with an interest in criminal justice reform. In 1892, Altgeld became the first Democratic governor of Illinois in more than 40 years.

As Lindsay’s poem describes it, Altgeld gave his enemies reason to snarl, bark, and foam at him until the end of his days. He decided to review the Haymarket case.

Cartoon titled “The Friend of Mad Dogs” showing Governor John Peter Altgeld releasing dogs (labeled Anarchy, Socialism, Murder) who run toward a woman and children. From Judge periodical, published by Judge Publishing Company in New York, New York, vol. 25, no. 613, July 15, 1893. Statue of Haymarket in background. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum, ICHi-031336

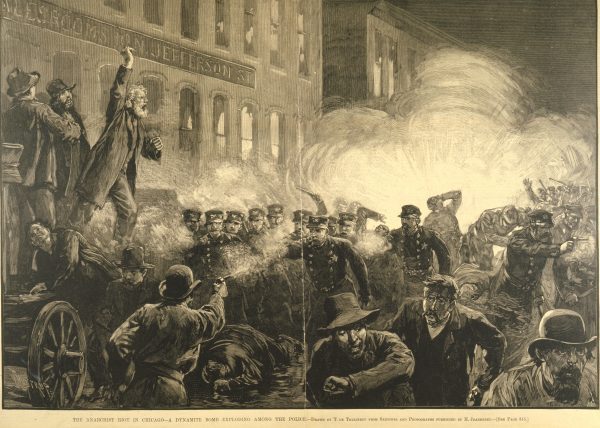

The story begins the evening of May 4, 1886, when almost 3,000 Chicagoans gathered in the area known as the Haymarket to support an eight-hour workday and protest a previous act of police violence. As the peaceful gathering neared its end, almost 200 armed police marched into the crowd. Someone threw a bomb. One officer died instantly; seven others later succumbed to their wounds. Dozens of people were injured.

Illustration depicting the bomb detonating on May 4, 1886, published in Harper’s Weekly, May 15, 1886. Title reads “The anarchist riot in Chicago – a dynamite bomb exploding among the police.” CHM, ICHi-003665

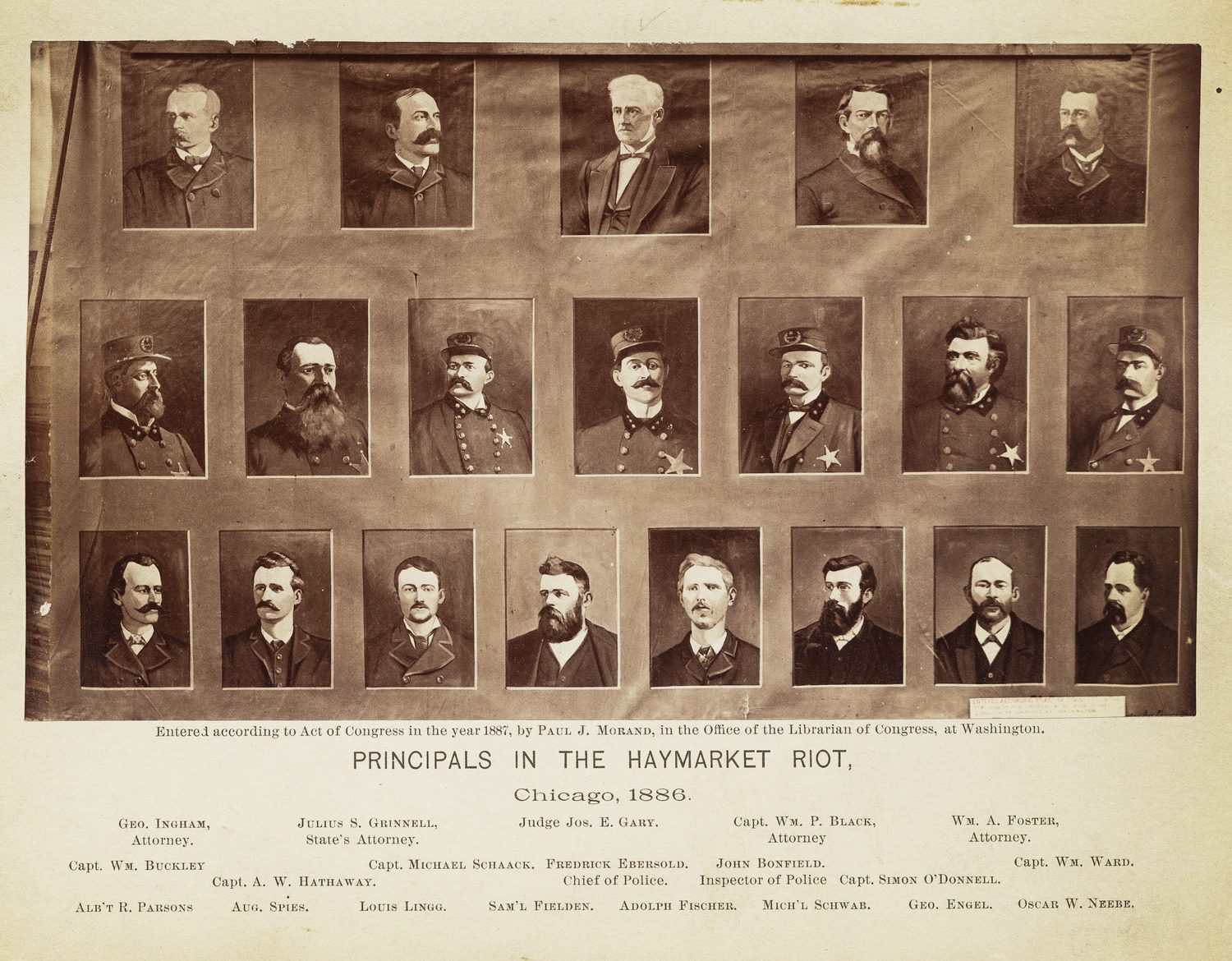

A terrorist act of this kind had never occurred before, and the public panicked. Unable to identify the bomber, the state arrested and tried eight men, mostly foreign-born, who identified as socialists and anarchists and had been involved in the Haymarket gathering. Condemned for what they said and believed, Albert Parsons, August Spies, Adolph Fischer, and George Engel were hung; Louis Lingg died by suicide in prison; and Samuel Fielden, Michael Schwab, and Oscar Neebe went to the state penitentiary in Joliet.

Photographic print titled “Principals in the Haymarket Riot” dated 1886 depicting the judge, attorneys, police, and defendants involved in the Haymarket Affair. CHM, ICHi-003678

Reviewing the court records, Altgeld determined that the Haymarket trial was biased against the defendants, the witnesses for the prosecution had perjured themselves, and the police had tampered with evidence.

Undated photograph of the front of the Haymarket Martyrs’ Monument at Waldheim Cemetery (now Forest Home Cemetery), Forest Park, Illinois. The quote at the base reads: “The day will come when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you are throttling today.” CHM, ICHi-052313

“I will simply say in conclusion on this branch of the case that the facts tend to show that the bomb was thrown as an act of personal revenge,” Altgeld wrote, “and that the prosecution has never discovered who threw it, and the evidence utterly fails to show that the man who did throw it ever heard or read a word coming from the defendants.”

On June 26, 1893, Altgeld pardoned the men imprisoned in Joliet–Samuel Fielden, Michael Schwab, and Oscar Neebe.

Statue of John Peter Altgeld by sculptor Gutzon Borglum in Lincoln Park near Diversey Avenue and Sheridan Road, Chicago, April 1975. CHM, ICHi-067212

This act of political courage, along with his support of workers during the 1894 Pullman Strike, ensured Altgeld’s reelection defeat. National attitudes did not match his personal values, but Altgeld would inspire other reformers like Jane Addams and his former aide Clarence Darrow. Upon Altgeld’s death in 1902, the always critical Chicago Tribune felt forced to conclude, “The hatred of his opponents was a tribute to his ability.”

Additional Resources

- Peruse The Dramas of Haymarket, an online project produced in partnership with Northwestern University that examines select materials from our extraordinary Haymarket holdings

- The Museum’s Chicago: Crossroads of America exhibition discusses the Haymarket affair in the City in Crisis section.

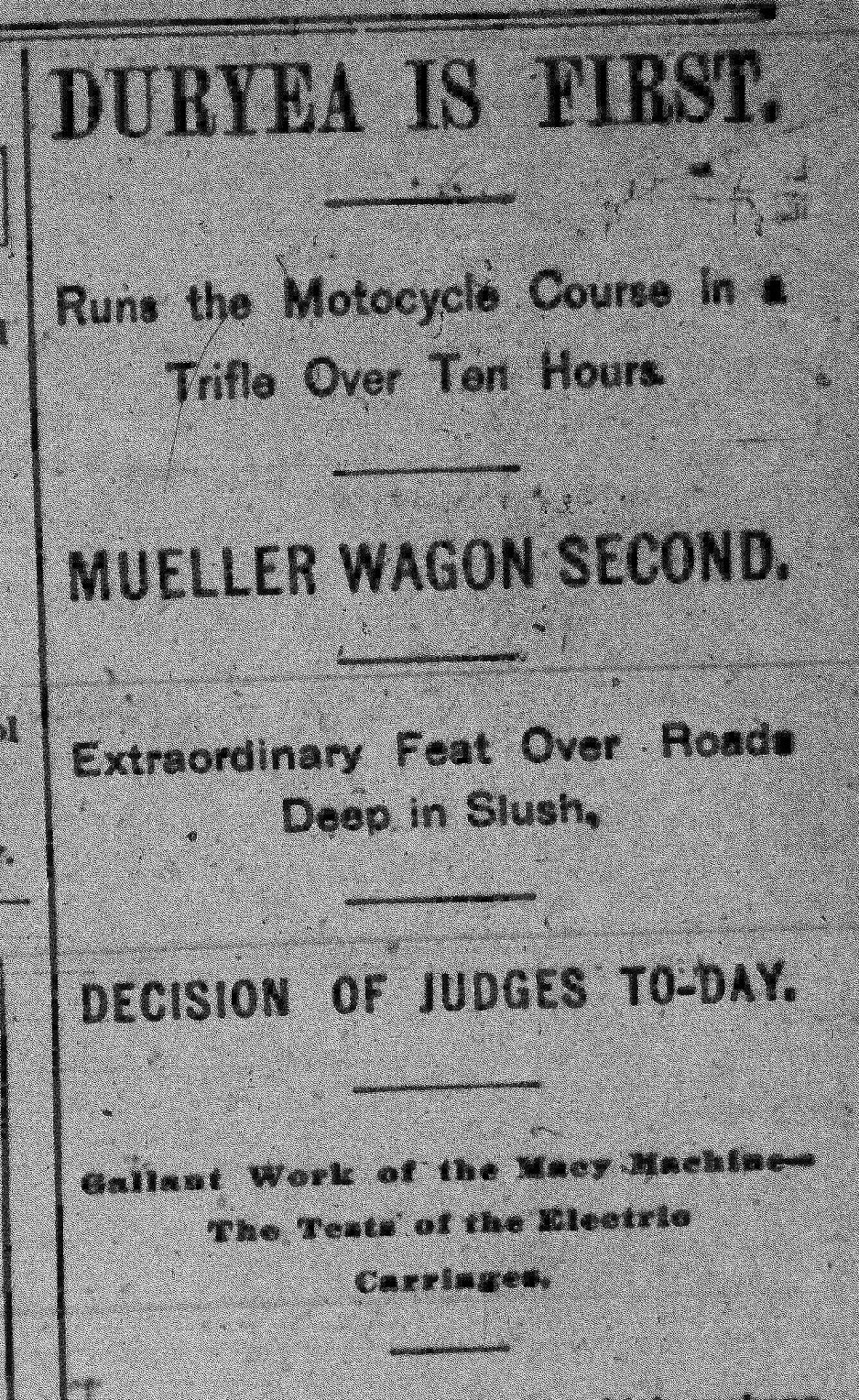

NASCAR is hosting its first ever street courses during the 2023 Fourth of July weekend right here in Chicago, inaugurating two separate races, the 100-lap Grand Park 220 and the 55-lap Loop 15. The Windy City is no stranger to automobile competitions. In 1895, the Chicago Times-Herald Race, the nation’s first automotive race, took place in Chicago and changed the course of US history.

Herman H. Kohlsaat, head-and-shoulders portrait, c. 1903. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/00652040/.

The competition was the idea of Herman Henry (H. H.) Kohlsaat, who made his fortune as an entrepreneur in the food industry and a newspaper publisher. Kohlsaat got the idea from a race that ran in 1895 from Paris to Bordeaux. His rationale for hosting one was two-pronged. He believed that travel by horse carriage would soon become a thing of the past due to the rapid pace of technological advancements, and hosting a race was a unique way to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the Chicago Times-Herald, of which he was the proprietor.

The race was originally scheduled to take place on July 4, 1895, to take advantage of the crowds already gathered in the city. However, the date was pushed back when many competitors requested more time to complete their racing machines. As part of the campaign to promote the competition, Kohlsaat held a contest in the Times-Herald asking readers to submit nominations for what they thought the new “self-propelling road carriages” should be called. After receiving many submissions, the newspaper declared “motocycle” the worthiest term, awarding the entrant a prize of $500 ($18,100 in 2023). Kohlsaat ended up rescheduling the Times-Herald Race for Thanksgiving 1895. Up for grabs was a $5,000 pot: $2,000 for first place, $1500 for second, $1000 for third, and $500 for fourth. (In 2023, $72,411 for 1st, $54,308 for 2nd, $36,206 for 3rd, and $18,103 for 4th).

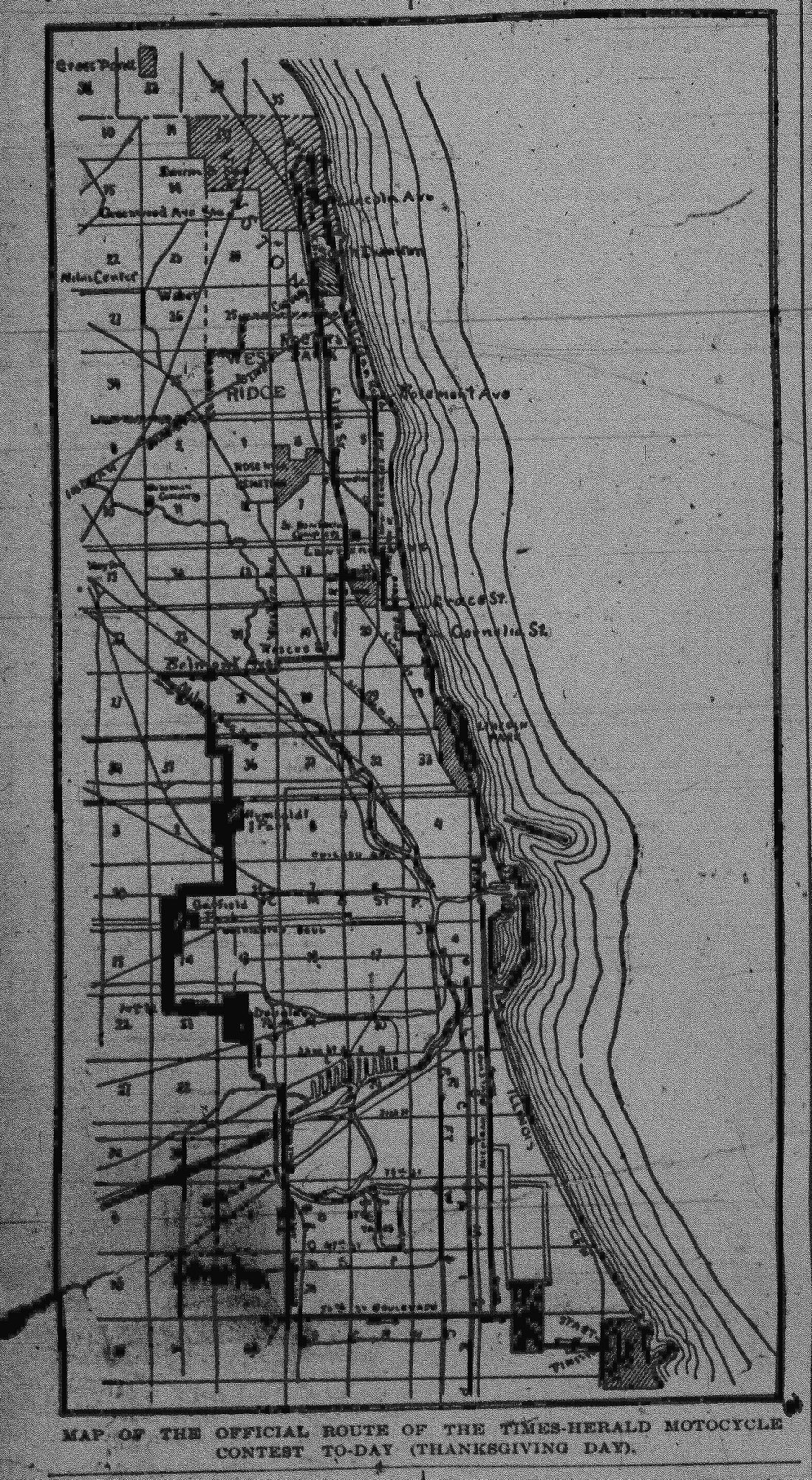

Map of the official route of the Times-Herald motocycle contest, from page 2 of the Chicago Times-Herald, November 28, 1895.

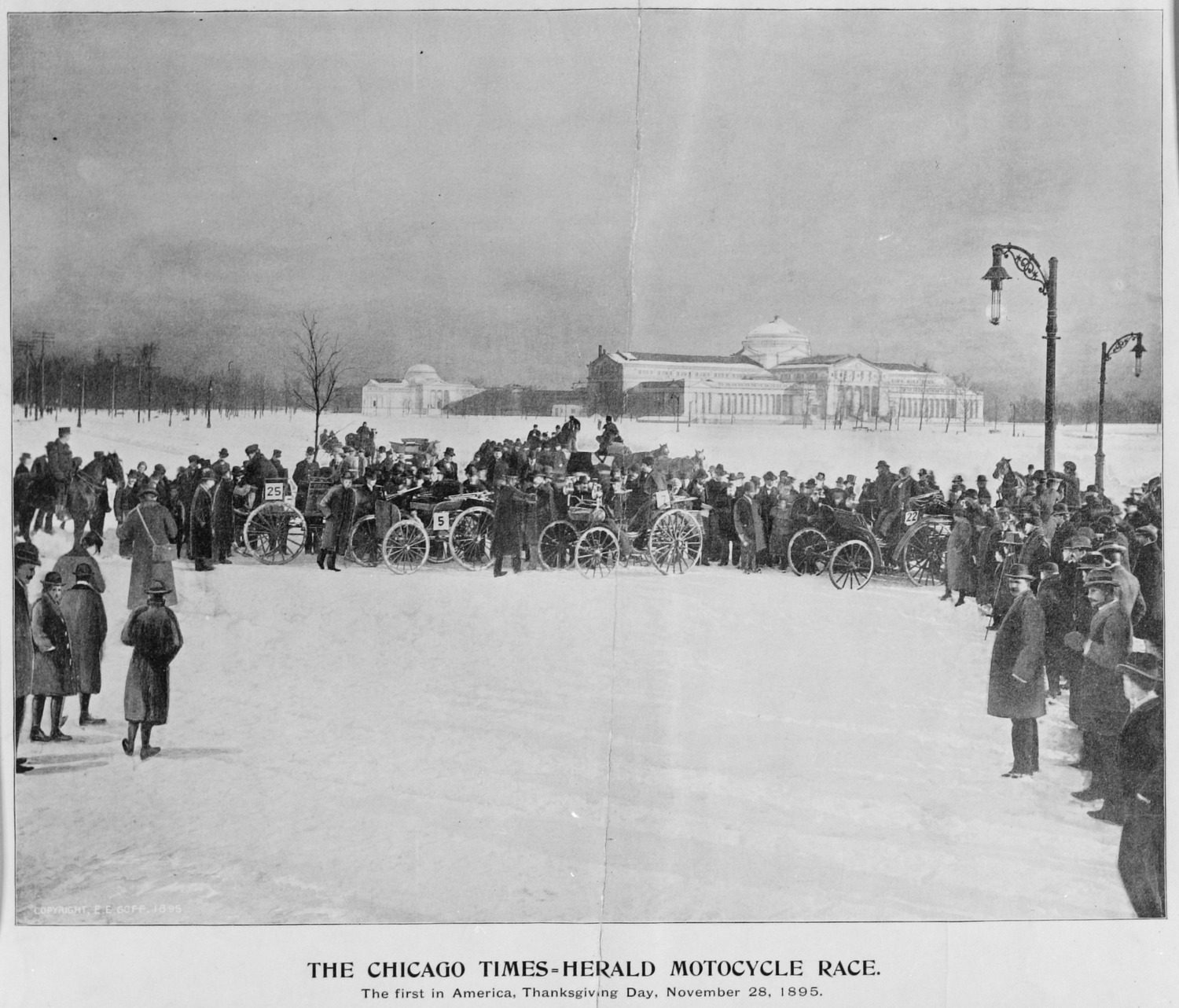

What few accounted for was Chicago weather in November. Initially, 80 competitors registered for the competition, but the night before the race, a snowstorm coated city streets with six inches of snow, which brought down the number of committed racers to eleven. At the morning lineup, only six vehicles made it to the starting line at the Midway Plaisance. While the original race plans had drivers going further north, the blizzard led to a significant modification in the track. Drivers would complete a loop from the city’s South Side to north suburban Evanston and back again. Altogether, the official distance of the race measured just over 50 miles.

The start of the Chicago Times-Herald motocycle race, the first in the United States, on Thanksgiving Day, November 28. 1895. CHM, ICHi-003646

The six vehicles that lined up at 9:00 a.m. on race day were feats of engineering. Four of the six competitors powered their vehicles with gasoline. Three of the four gasoline vehicles were built by German engineer Karl Benz, the namesake of modern-day Mercedes Benz. One was sponsored by Hieronymus Mueller & Co. from Decatur, Illinois, the second by the De La Vergne Refrigerating Company, and the third by RH, Macy & Co., both of New York. The fourth gasoline-powered vehicle was the Duryea, made by the Duryea Motor Wagon Company based out of Massachusetts. The other two vehicles were electric and participated in the race not as serious contenders but instead to showcase the potential of electric drivetrains. The Morris and Salom Company from Philadelphia sponsored one, dubbed the Electrobat, while the other belonged to Chicagoan Harold Sturges, previously exhibited at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

J. Frank Duryea, designer, builder, and driver of the automobile that won the Chicago Times-Herald race, with umpire Arthur W. White, November 28, 1895. CHM, ICHi-009009

The race was anything but high speed. Thanks to the weather, road conditions, and primitive engineering powering the vehicles, the average speed at which cars traveled the course was a whopping seven miles per hour. Additionally, every competitor needed to make space for a race umpire in their vehicle, who ensured that drivers kept to the course. After many starts, stops, and a breakdown or two, the American-made Duryea was the first to cross the finish line, logging over 10 hours on the road. Second place came to the Mueller Benz from Decatur. These two were the only competitors who completed the race, with the rest dropping out due to damage to their vehicles or equipment malfunctions.

Front page of the Chicago Times-Herald on November 28, 1895, with a recap of the race.

Ultimately, the Times-Herald Race started what would become a revolution. Six years later, the first Chicago Auto Show was organized in 1901 to showcase the reliability and power of the personal vehicle, marking the start of an automotive tradition that has spanned more than a century of automotive development. Chicago also continued its history of motorsports well into the twentieth century. During the 1940s and ’50s, stock car racing made Soldier Field one of the premier venues in the nation for racing aficionados.

Additional Resources

- The Hieronymus Mueller & Co Benz can still be seen today, as it’s on exhibit at the Hieronymus Mueller Museum in Decatur, IL.

- Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on the Chicago Times-Herald Race of 1895.

- Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on the history of motorsports in Chicago.