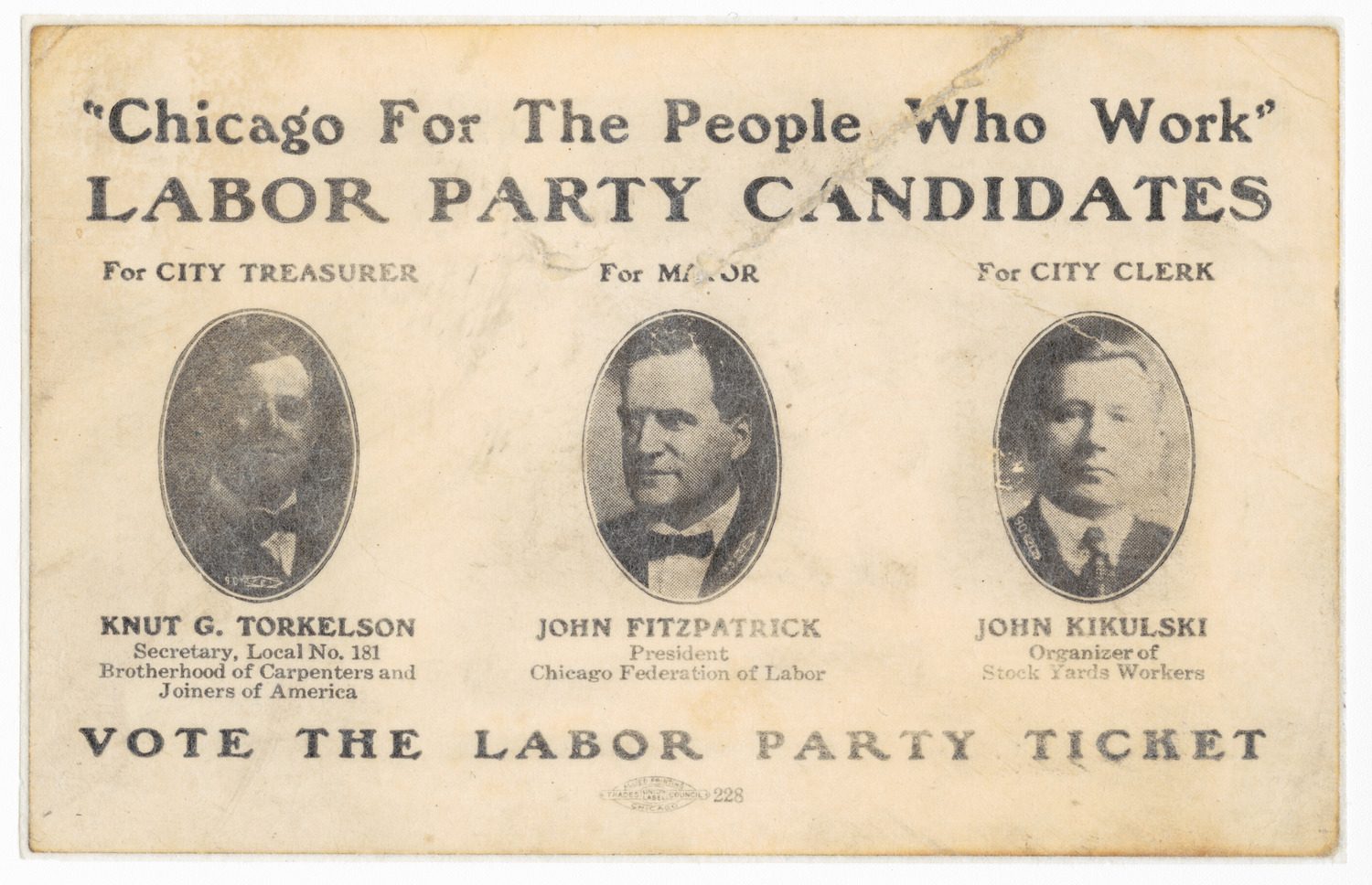

February 2024 marks 110 years since the start of a labor action commonly known as the Henrici’s restaurant waitress strike. In this blog post, CHM editor and content manager Heidi Samuelson recounts the strike, its history, and its effects.

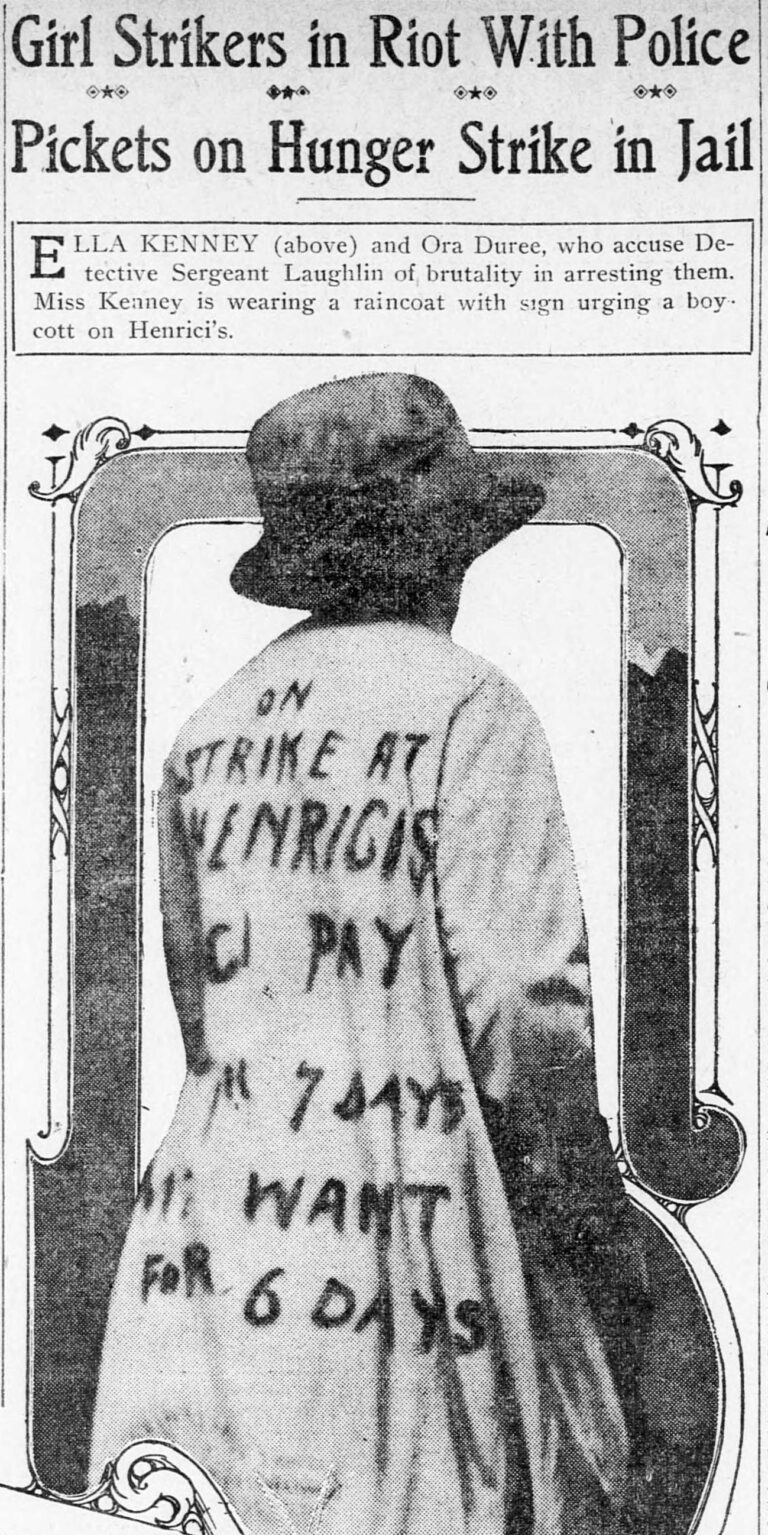

“Girl Strikers in Riot with Police,” Chicago Examiner, February 10, 1914

In February 1914, four waitresses marched through a lunchtime crowd outside Henrici’s restaurant at 67 West Randolph Street wearing coats painted with their demands: “On strike on at Henrici’s. Henrici’s pay $7 for 7 days. We want $8 for 6 days.” When police tried to arrest them, the “girl strikers” sat down and refused to go without a fight. They were later charged with encouraging an illegal boycott.

The waitresses were members of Chicago Waitresses Union Local 484 who, along with the Chicago Cooks Union 864, organized a strike to demand recognition of the waitresses’ union, a living wage, and better working conditions. Henrici’s was selected as the first target of their picketing, after owners had promised to fire any waitresses who joined the union. The restaurant manager at Henrici’s told reporters their waitresses were asked but “unwilling” to join the union.

Mabel Burke, a union member, being arrested for conspiracy and illegal picketing, February 1014; DN-0062302, Chicago Daily News Collection, CHM

For weeks, the sidewalk outside the restaurant was picketed by women encouraging patrons to boycott the establishment. The picketers were frequently arrested, as police often sided with businesses during workers’ strikes.

Ellen Gates Starr after being arrested for interfering with the waitress strike in front of Henrici’s restaurant, March 19, 1914; DN-0062287, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Among those arrested was Ellen Gates Starr, cofounder of Hull-House and a member of the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL), who had lent her support to the strikers. Starr noted in her essay “Efforts to Standardize Chicago Restaurants—The Henrici Strike” that although Illinois law permitted peaceful picketing, the police sometimes arrested the same woman twice in a day, and yet none of the strikers’ cases was ever tried.

The Chicago WTUL was founded in in 1904 and was one of the most active branches of the national organization, which aimed to organize women workers into trade unions, lobby for protective legislation and woman suffrage, and promote vocational education. The WTUL was a mix of middle-class and working-class women. By 1910, it had deepened its alliance with the Chicago Federation of Labor, promoted the leadership of working-class women, and played a key role in the 1910–11 garment workers’ strike—supporting striking workers and their families and helping draft the agreement to end the strike.

Front cover of pamphlet titled “The Eight Hour Fight in Illinois by The Girls Who Did the Work,” leaflet no. 4, published by the Chicago WTUL, 1909; CHM, ICHi-177353

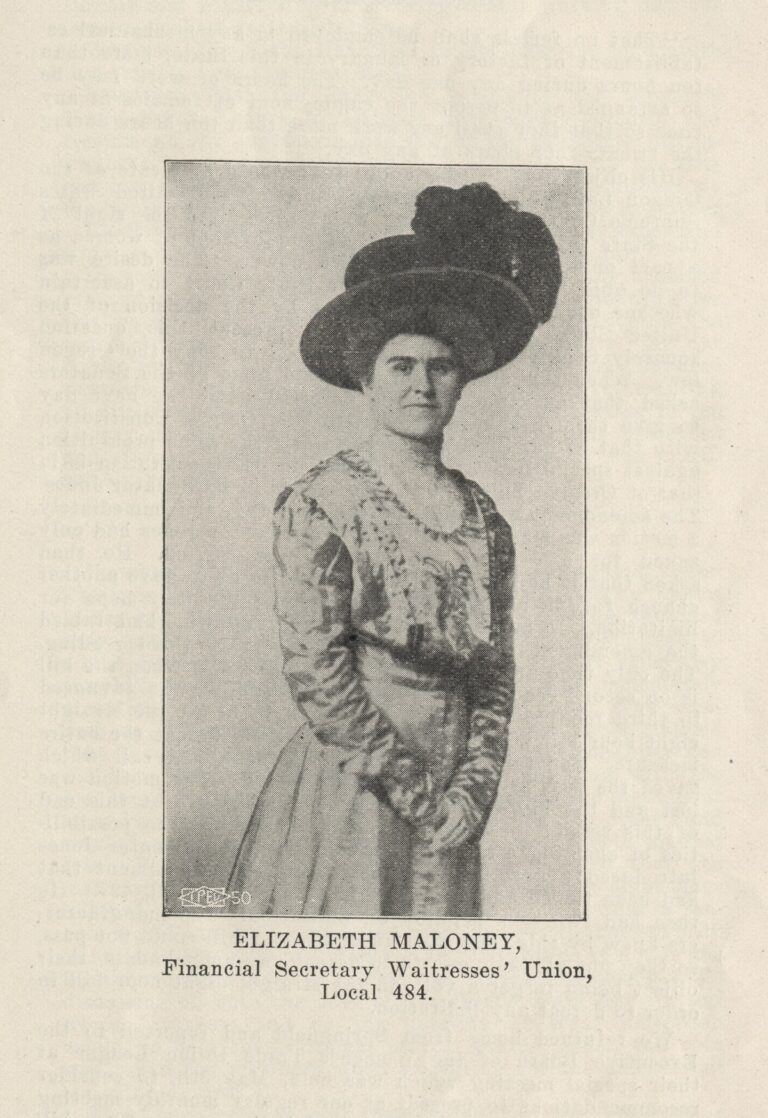

The 1914 waitresses’ strike expanded to twenty more restaurants that were all part of the Restaurant Keepers Association. Though it eventually collapsed due to a series of injunctions against the picketers, it gained significant press attention. Due to this attention, Elizabeth Maloney, a WTUL board member and one of the Waitresses Union Local 484 founders, testified before the Commission on Industrial Relations, or the Walsh Commission, created by US Congress in August 1912 to evaluate US labor law and working conditions.

Portrait of Elizabeth Maloney, financial secretary of the Waitresses Union Local 484, Chicago, c. 1909. CHM, ICHi-067690

During her testimony Maloney said:

“When you look at the profit side of the concern and look at the wage column, and see the wages as low as two or three or four dollars a week, and you know that industry is piling up millions of dollars at the expense of the girls, that side of the table should be equalized a little more, and I think a girl should be entitled to live decently and properly and enjoy some of the things in life that her employer wants his children to have.”

Additional Resources

- Learn more about women’s labor actions in “Underpaid, Undervalued,” part of our online experience Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote

- Find materials from the Women’s Trade Union League of Chicago in the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is always free to visit