To mark Labor Day 2023, CHM editor Heidi Samuelson writes about Polish-born John Kikulski, a Chicago labor leader in the early twentieth century. You can see more about Kikulski in our exhibition Back Home: Polish Chicago.

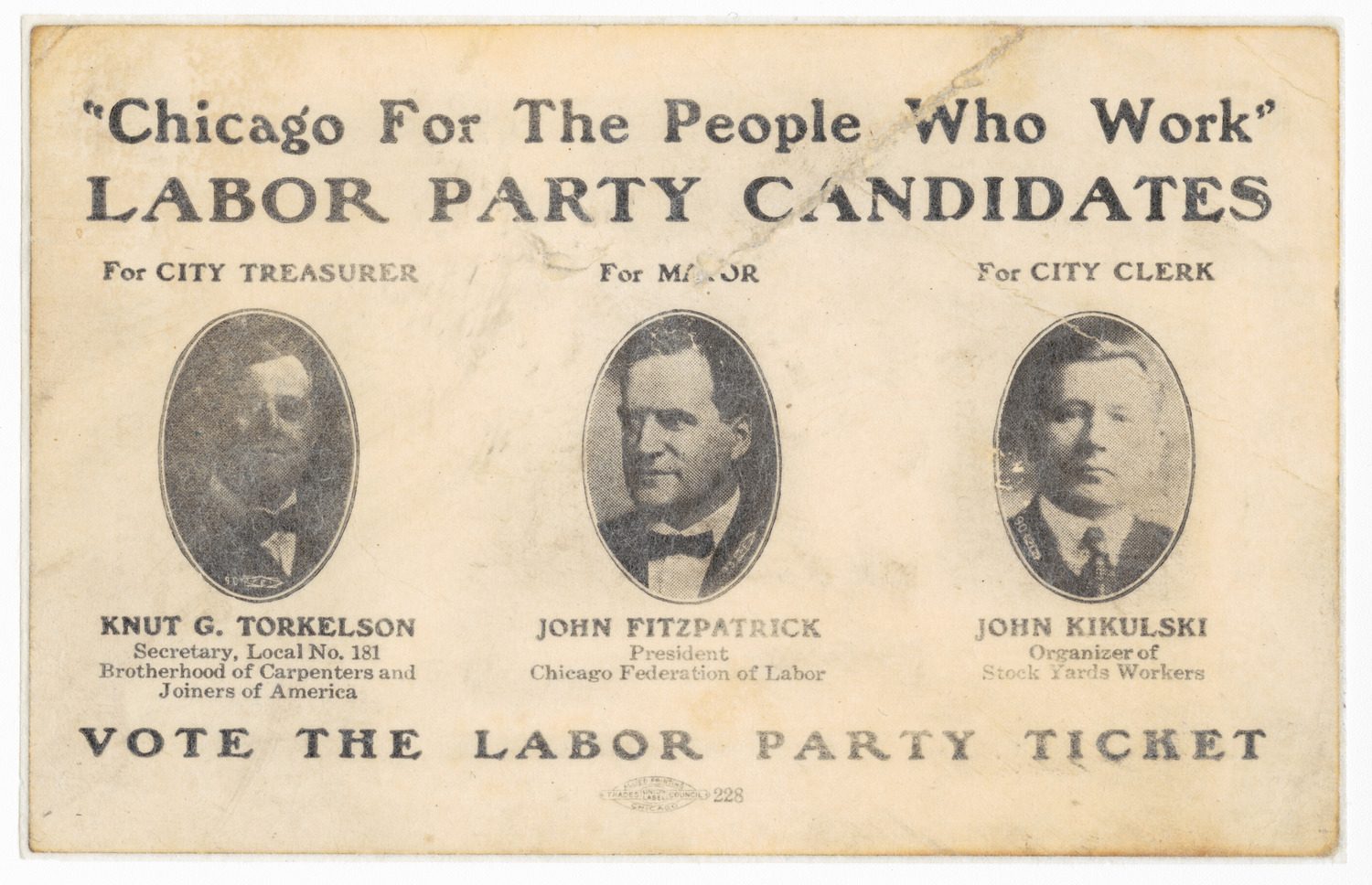

Labor Party candidates palm card, Chicago, 1919; CHM, ICHi-182716-001

John Kikulski was born in the village of Okinin in German-occupied Poland in 1876 to Ludwig and Catherine (Graf) Kikulski. He received his elementary education in Poland, and likely immigrated to the United States around 1889. Upon arriving in Chicago, he attended night schools to learn English and found an apprenticeship as a wood maker. He became a US citizen, and in 1898 he married Mary Wajert of Chicago. The couple had two children.

Kikulski was active in Chicago’s labor movement from the late 1890s on. He became a labor official of the Wood Workers’ Union in 1901 and was later elected president of Local 14 after the union became amalgamated with the Mills and Factory Carpenters’ District Council.

Also active in Polish community organizations, Kikulski was a member of St. Hyacinth’s Parish and the Polish National Alliance, for which he served as director for one term in 1904. He also served as president of the Polish Falcons (now Polish Falcons of America) from 1910 to 1912. Kikulski’s first attempt to enter city politics came in 1903 when he ran for Sixteenth Ward alderman on the Independent Labor Party ticket and lost.

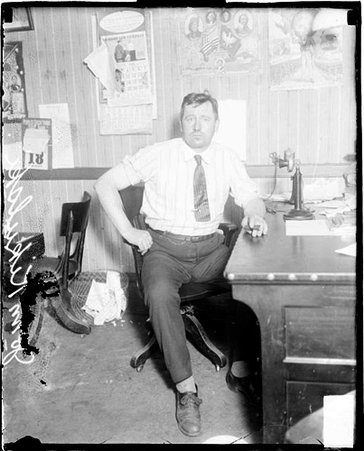

During World War I, Kikulski worked as an organizer for the American Federation of Labor (now the AFL-CIO) and helped to lead strikes at International Harvester and the Crane Company. In 1917, he joined the stockyards labor movement where he gained his greatest success. Packinghouse workers elected him president of the largely Polish Local 554 of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen and later secretary of the Stockyard Labor Council. The Stockyard Labor Council worked to unite Black and white laborers, men and women laborers, and laborers of various skill levels. They had the support of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters union and the Chicago Federation of Labor, and with the intervention of federal mediators gave workers higher wages and an eight-hour workday.

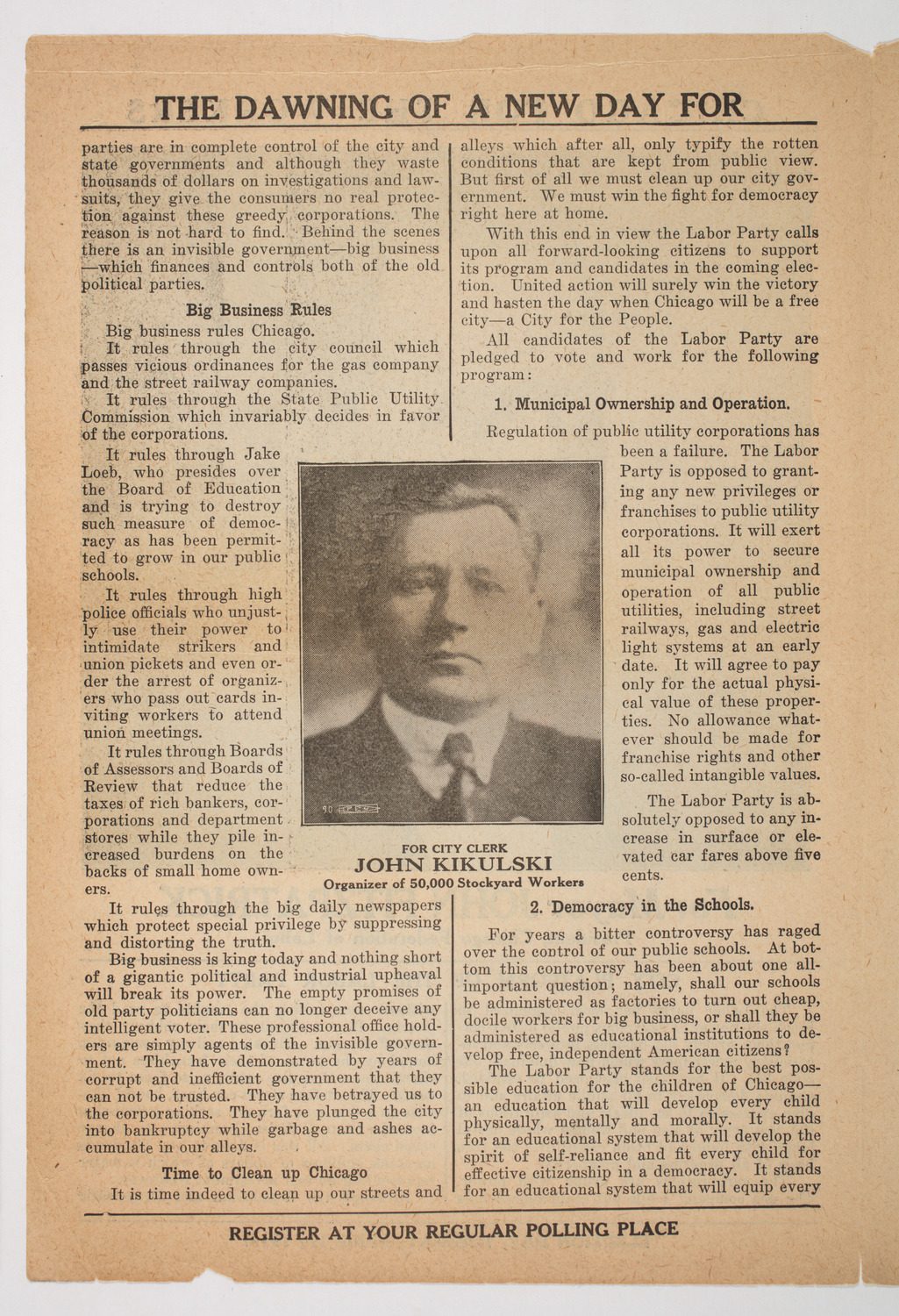

Second page of a political flyer for the Labor Party, which includes a portrait of John Kikulski for city clerk, in advance of election day on April 1, 1919, Chicago. CHM, ICHi-182719-002

Following the union’s success, members voted Kikulski director of District 9 of the meat cutters’ union. In 1919, he ran an unsuccessful campaign for city clerk as the Farmer-Labor Party candidate. As a candidate, Kikulski preached racial harmony and working-class unity, but the momentum gained in the stockyard movement was damaged by the race riots of 1919. The Chicago Federation of Labor issued a statement on August 9 accusing the packing houses of exacerbating the riots in a further attempt to polarize Black and white workers as well as denying Kikulski, J. W. Johnstone, and Martin Murphy of the Stockyards Labor Council entry to a meeting with superintendents of all the packing plants and police.

Informal portrait of John Kikulski in an office in Chicago, 1919. DN-0071292, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

Later that year, Kikulski defected from the Council and continued to be entangled in Chicago’s labor wars. Various factions accused him of embezzling money, though his working-class supporters remained loyal. However, on May 17, 1920, two unknown assailants attacked and shot Kikulski in front of his home. He died four days later. Kikulski received a hero’s burial as mourners filled St. Hyacinth’s Basilica beyond capacity. A procession of some two hundred automobiles escorted his casket to St. Adalbert’s Catholic Cemetery.