To mark Labor Day and Chicago’s long history of labor activism, CHM assistant curator Brittany Hutchinson recounts how the Pullman Company’s porters formed the first all-Black labor union in the US to address low wages, long hours, and mistreatment from passengers.

In August 1925, A. Philip Randolph was elected president the newly formed Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), the first all-Black labor union in the US. The union initially faced opposition not only from the Pullman Company, but also porters who were fearful of termination and members of the African American community who viewed George Pullman as an ally and credited him with providing lucrative employment opportunities for formerly enslaved men and women.

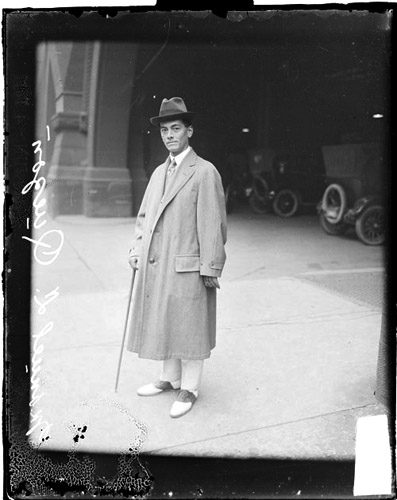

An undated portrait of A. Philip Randolph. CHM, ICHi-018048

A meeting of the BSCP in an auditorium, 1927. CHM, ICHi-025673

Following the Civil War, George Pullman sought to hire formerly enslaved men as sleeping car porters. The Pullman Company’s decision to hire Black men to serve as porters created an opportunity for economic advancement for newly emancipated African Americans and is often credited with contributing to the creation of the Black middle class. Despite these benefits, Sleeping Car Porters were often mistreated, both by their customers and the company.

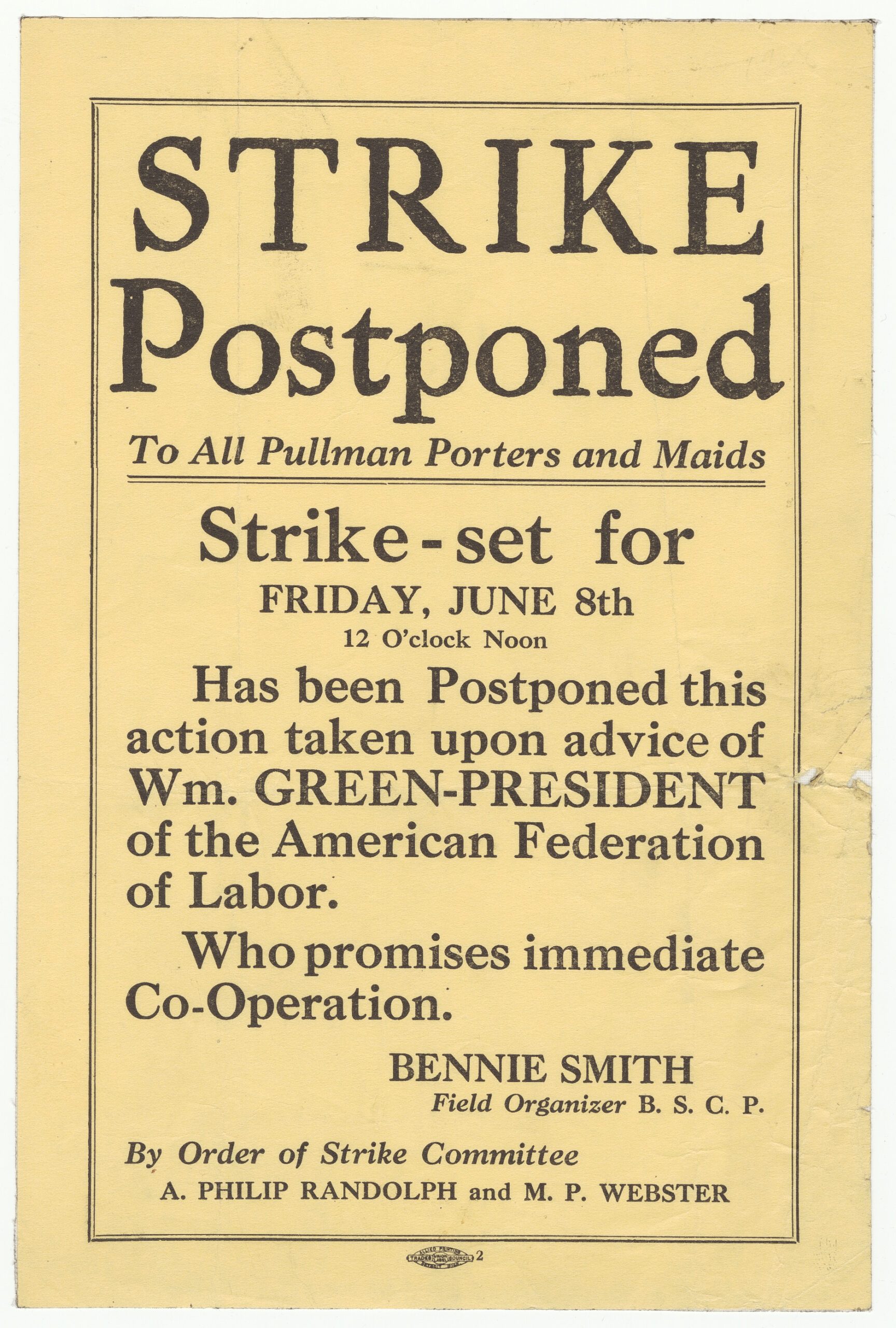

A broadside announcing the postponement of a Pullman porter strike, 1928. CHM, ICHi-061917

While employment as a Pullman Porter was eventually viewed as high-paying job, initially it was not. The wages were very low for the standards of the day, and porters would often need to work at least 400 hours each month to earn their full monthly pay. In comparison to other company roles, porters were paid the lowest salary and had to cater to the passengers’ every whim in order to earn tips. In addition to working long hours and receiving little pay, porters were subjected to unbridled racism. Despite some of the relatively positive outcomes for the Black community, Pullman’s decision to hire formerly enslaved men was rooted in the belief that former slaves would be fully acclimated to servitude and long hours. Passengers commonly referred to porters as “George” regardless of their name, continuing the demeaning practice of calling an enslaved person by their owner’s name. The combination of racism and inhumane working conditions led to calls for unionization.

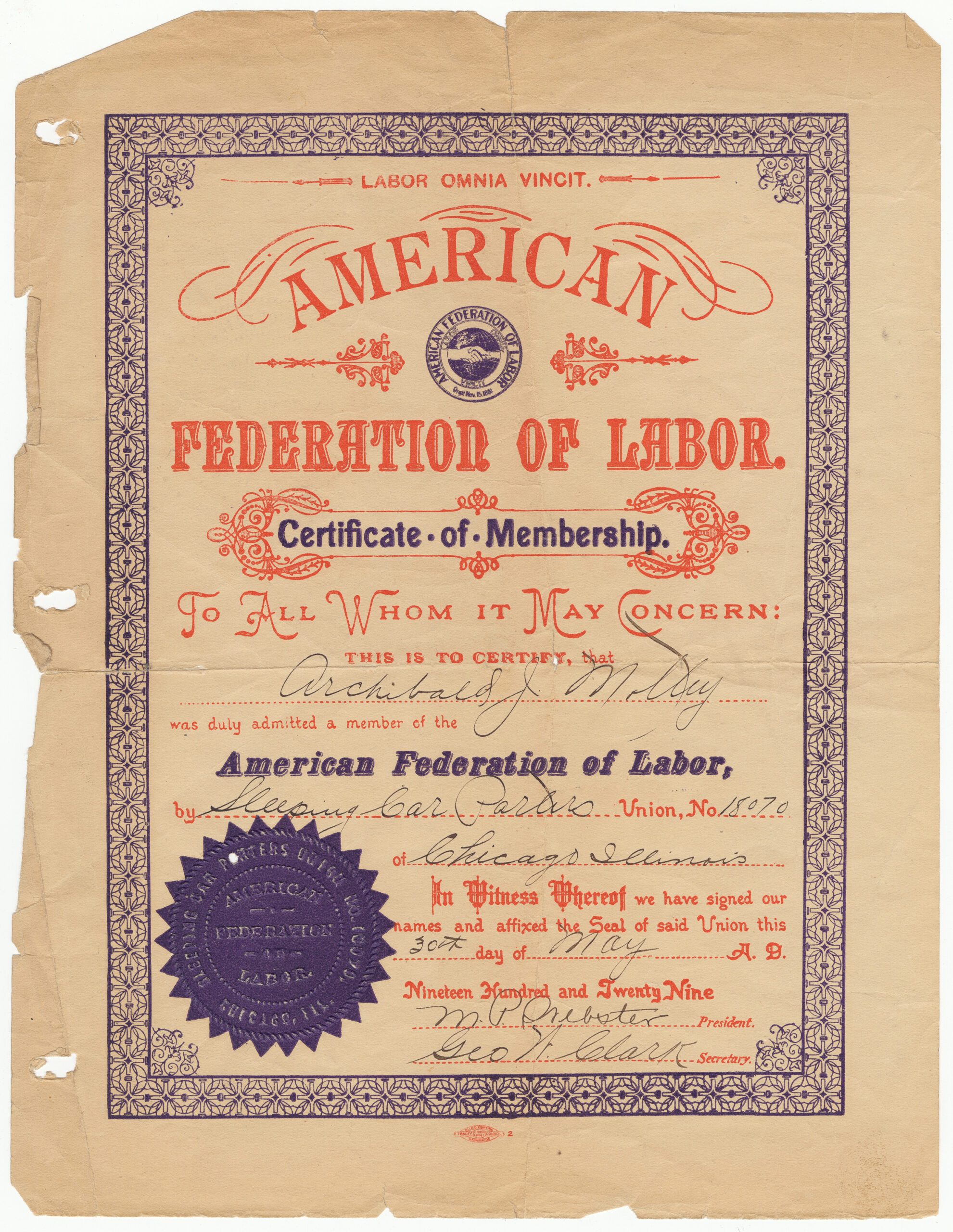

A certificate of membership in the American Federation of Labor through the Sleeping Car Porters for Archibald Motley, father of Harlem Renaissance artist Archibald Motley Jr., 1929. CHM, ICHi-061920

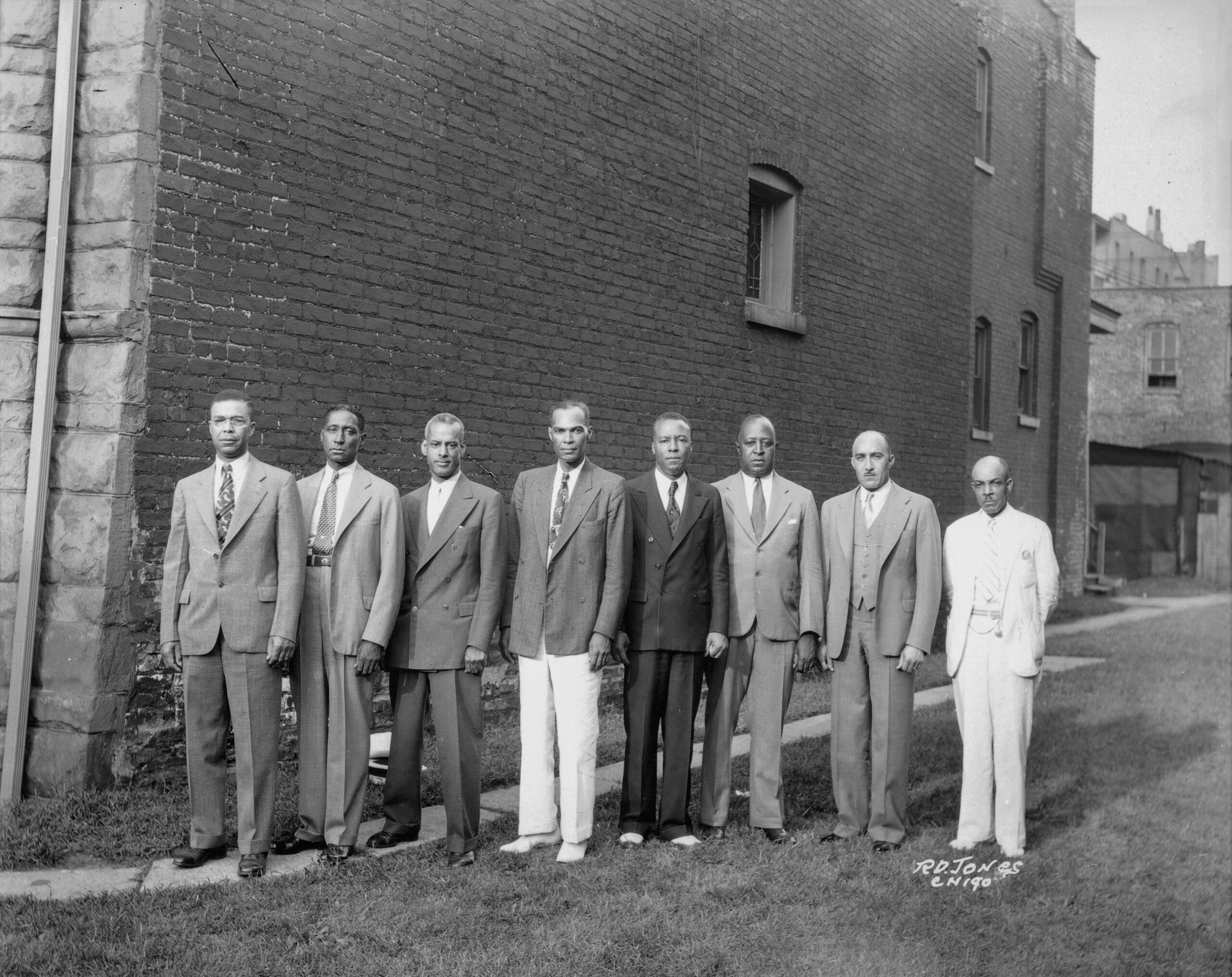

BSCP officers, c. 1935. CHM, ICHi-022642

In 1935, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters became the first African American union organization to be granted membership into the America Federation of Labor. The Pullman Company agreed to negotiations with the BSCP and in April 1937, after twelve years of resistance, a contractual agreement was finally reached which included an increase in wages and a cap of 240 hours per month.

Milton P. Webster, the first vice president and leader of the Chicago division of the BSCP, 1951. CHM, ICHi-024898

The BSCP’s influence in the labor movement included a role in assisting the Great Migration by dispersing information about job opportunities and greater equality for Black people in the North. As the passenger car industry declined after World War II, A. Philip Randolph and the BSCP became early and influential figures in the Civil Rights Movement, as the fight for labor rights is inextricably linked to civil rights.

Join the Discussion