Critical Museum Observation in Action

Planning for UIC Undergrads to Comment on “Chicago: Crossroads of America”

A conversation between Drs. Elena Gonzales and Emmanuel Ortega, January 2023

Chicago History, Vol. XLVII, no. 2

In Fall 2022, the students of Emmanuel Ortega’s Introduction to Museum and Exhibition Studies course at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) collaborated with Elena Gonzales, curator of civic engagement & social justice at the Chicago History Museum (CHM), to critique and constructively comment on the Museum’s central exhibition Chicago: Crossroads of America, which is in a planning grant from the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation that will ultimately result in an update to this seventeen-year-old exhibition over the course of the next several years. Dr. Ortega’s students have taken over Chicago History magazine in this special issue to share their assessments and ideas about Crossroads and other exhibitions within CHM, as well as the forthcoming exhibition Aquí en Chicago, in an ongoing conversation about how we can collaborate to support CHM’s new vision to be one of the most trusted and inclusive cultural institutions of our collective history.

Dr. Gonzales spoke to the class in October 2022 and oriented the students to her work as a curator and the work CHM is doing on its central exhibition. The students then visited CHM independently, completed the Critical Museum Observer’s Guide, newly updated by CHM’s Education Department, and wrote on one of several questions relating to their visit. This brief introductory conversation between Drs. Gonzales and Ortega will situate the work of the students in the context of ongoing scholarship and practice at both CHM and UIC

Elena Gonzales: Could you tell me a bit about what your students are doing with this assignment? What is your class all about, and how did you come to want me to work with you and the class?

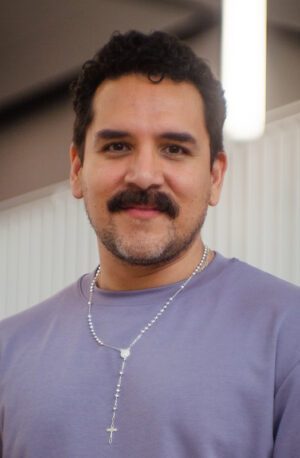

Emmanuel Ortega: I am an assistant professor in the department of Art History at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC). I am also the Marilynn Thoma Scholar in Art of the Spanish Americas. I preface my answer with this title because my approach to this specific class, that is, Introduction to Museum and Exhibition Studies, was a bit unorthodox for this semester. We are in the process of revamping our minor in Museum and Exhibition Studies, and I was assigned to teach this class to understand a bit more what our students needed and were most eager to learn. This class was highly diverse with students from many groups being represented. However, I would say that roughly 35% were of Latino background. In total we had 35 students enrolled.

From the start, I presented the class with a series of ethical conundrums that problematized the study of museums and exhibition spaces. We looked at the perils of authenticity and empathy, the politics of monuments, and the history of institutions that continue to disseminate colonial ideals of race, class, gender, and national identification. I was happily surprised to see how well students understood this information. This was the first time I was back in person after almost two years of pandemic Zoom courses. The lively interactions in person made for an incredible semester and critical space. I was eager to hear their opinions regarding the ways local museums aim to represent the local, the national, and the universal through their halls and galleries. It is with this premise in mind that I reached out to you to see how my students could interact with the Chicago History Museum. Your work inspired us all to come up with a series of questions we could answer, especially regarding the critical ideas we studied throughout the semester.

I love the ways in which social activism turned your position into a permanent one. Can you tell me a bit more about how this process changed your approach to the museum space and how this exercise with my students aims to continue the larger mission of social justice?

Gonzales: It’s true—I began work at CHM back in summer of 2021 as a contractor, curating Aquí en Chicago, an exhibition that centers the protest of CHM by students from Rudy Lozano Leadership Academy (Instituto Justice and Leadership Academy). It shows how the work of the students stands on generations of Latinos in the city going back more than a century. The persistent presence of these communities is the students’ legacy, as is the work of these communities. This ranges from the deceptively simple practices of raising culturally aware families, building businesses, and making public expressions of culture, such as murals, to more overt resistance to white supremacy and colonialism through protests, walk outs, strikes, and the like. I’m still working on this project—the exhibition opens in fall 2025—but in October 2022 I joined CHM full time in this curatorial position, which is a new one for the Museum. I’m very excited about the way Charles E. Bethea, the Museum’s director of curatorial affairs, is building the curatorial department so that we can best support the Museum’s new vision. The creation of this position was part of that work, as was the creation of another new position at CHM. Rebekah Coffman joined CHM as the curator of religion and community history in spring 2022, and our positions work in tandem in many ways.

The process of moving from contractor to full-time employee was very organic for me because of how welcoming and inclusive my colleagues were of me from the beginning. We began work on my project through a very open conversation about the overarching changes that would be taking place at the Museum and how my project would fit into that process. However, there have been certain important changes that have come through the process. Two important ones come to mind. First of all, my new position has made the Museum’s investment in change, inclusive history, and a holistic history of Chicago clear. My collaborators on Aquí can see that my work on this project is not set up to be an isolated effort but rather part of a larger long-term institutional plan.

Secondly, my new position allows me to fully engage my expertise in our work at CHM. I believe that one of the reasons CHM sought me out for the contractor position initially was my book, Exhibitions for Social Justice. I use it to explore ways of using the space inside the gallery to work for social justice, as well as ways to shift our institutions to better work for social justice overall. My new position at CHM mirrors this. I am working on an exhibition where we are contending with a long history of marginalization of Latino/a/x people in Chicago generally and CHM specifically. And I am helping to institutionalize practices at CHM that will find and dismantle our own unintended biases, making us a better partner, neighbor, and steward of all Chicago history. This is a collaborative effort among the staff, directors, president, and board, and I’m just one member of the team. Long story long, I’m afraid, the process of shifting to the new position gave me a greater sense of agency to make change at CHM toward practices of inclusivity and made my agency visible to all kinds of stakeholders, thus making it more possible to do my work.

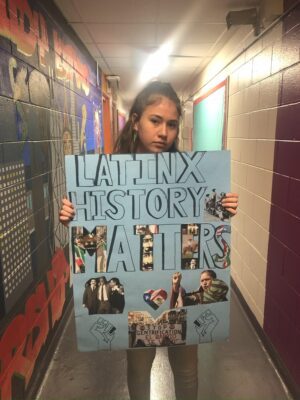

As for your students, I was very excited when you first brought up the prospect of my working with them back in summer of 2022. Your course seemed like the perfect laboratory for the ideas that I’m exploring through my job and that CHM is grappling with as an institution: authenticity and authority, decolonization, antiracism, and allyship. I mentioned the planning project—“Broadening Narratives”—that the Museum is undertaking through the current Donnelley grant. Bringing a diversity of stakeholder voices to bear on Crossroads is a key part of this planning work that will help CHM remake its central exhibition over time. Your students are an ideal group to include in many ways: the Museum is actively seeking ways to better engage younger audiences of color. In addition, of course, your students have the expertise from your class to analyze museum work. My work on Aquí has brought me close to the stories of students whose protest forms the heart of the exhibition.

One of our methods for honoring and inhabiting the experience of the students from Rudy Lozano/IJLA has been to include young Latino/a/x people in this project in as many ways as possible. Thanks to a grant from Bank of America, Latino/a/x high schoolers from around the area will be interning on the project as researchers in the summers leading up to the opening. We have also been fortunate to bring in MA and PhD students onto the project during the academic year in a similar capacity. The project with your students is different, in that they are working mostly on Crossroads rather than Aquí and doing evaluation rather than research, but I feel that this is a very resonant way that we can take the practices and lessons from Aquí and use them in other ways throughout the Museum. That’s one of the benefits of my new position, and I’m delighted that these students have a place to participate in shaping the CHM of their generation.

The students recognize the power and responsibility of museums such as CHM. Were there any areas of consensus or overarching themes that rose to the surface? Can you share a bit about what we’ll encounter when we read the reactions and analysis of the students? And how do you think the students have felt about the assignment and participating in this process?

Ortega: Yes, in fact, I began this and many other classes by discussing the importance of dynamic language. This is something I learned from my advisor Kirsten Pai Buick at the University of New Mexico. The idea behind dynamic language is to allow for some running themes and ideas to be placed in the realm of the process. For instance, one major concern with this class was the idea of authenticity. More specifically, the ways in which we interact with it in museums. How important is it to encounter authentic objects in the museum? For what reason? Who benefits from this authenticity? etc. However, in order to ask these questions we had to change our mindset from authenticity to authentication. This is what I meant by talking about dynamic language. We don’t speak about authenticity but about authentication; we don’t speak about identity but about identification. That way we can formulate questions in terms of process. For instance, who authenticates and for what reason? Who has historically profited from authentication? For whom do we authenticate? That way you avoid anchoring ideas to one single answer and instead, you are pushed to investigate process. So, in order to arrive at your project, we explored the history of museums and exhibitions from these types of critical standpoints. By the time we formulated the questions presented here, we already had an idea how authenticity functions. For that reason, a lot of the answers center on this theme.

Another major theme that came about in a more organic way was the issue of representation. Without directly addressing the erasure of minoritized communities from museums around the world, we always understood the historical processes of exclusivity and inclusivity affecting these institutions. One of the assignments was to visit an encyclopedic museum and see how they attempt to represent the world. I asked them to look at the labels, the display props, the text, and even the colors of the walls. I was surprised by how learning about the history of exclusion enabled many students to observe curatorial practices of exclusion. Again, always thinking about the process. This is, without a doubt, my most outspoken class to date. We engaged in such generative conversations that going to class was always a joy. I feel like there was a shift after the pandemic. There was a need for social interaction, and it shows. Normally small classes of undergraduate students tend to be a bit quiet. Many are fresh from high school and are only beginning to find their voices in the classroom. However, this group was different, and after talking to you about the possibility of sharing their voices with your visitors, I knew this was the best group.

I am eager to see the ways in which you integrate the opinions from school communities. While I see an attempt from many museums to try to integrate surrounding communities in the conversation, you seem to come from a much more critical standpoint. Can you tell me how you blend your academic and social justice practices into spaces such as CHM?

Gonzales: I’ve never thought about the process of authentication as you described it—in terms of the process itself—though it is so central to the way the museum confers value, through the “museum effect” as Svetlana Alpers put it (“Museums As a Way of Seeing,” Exhibiting Cultures). It’s fascinating how your class entered through this idea. Visiting the class, I also found the students to be exceptionally outspoken and engaged, as you suggested, which made the class fun, interesting, and energizing. I knew it would be so exciting to hear from them in this venue!

Integrating students’ voices in curatorial work generally and in Aquí, my current project, specifically is a challenge for several reasons. Students are often only able to focus on the curatorial work to the extent that it takes place within a class. So, for example, the students from Rudy Lozano/IJLA protested CHM within the context of their classroom work with their history teacher. They took that initiative and did a great deal of work, but once the class was complete, most of them moved on to other things.

In addition, we learned quickly that there are barriers to participation by teens in work at CHM. We’ve worked to remove as many of these barriers as possible (offering paid internships with hybrid work schedules and support with transportation and food while working on site) and to clearly identify those we can’t remove (such as background checks and vaccine mandates) so that young people can make informed choices about seeking employment at CHM. We were fortunate to engage with some students and alumni from Rudy/IJLA in 2021. One alumnus, Jair Ramirez, still sits on our Advisory Committee for Aquí, and we are eager to welcome other students and alumni from Rudy/IJLA into the project at any time, either as advisors or as interns on the project. Those two vehicles—the Community Advisory Committee, which consults on every part of the project, and the internship program for Latino/a/x people ages 16–20—are the ones we are using to include students’ voices in Aquí.

Since high school students started us off on the path toward Aquí en Chicago, it felt necessary to ensure that they could contribute throughout. We immediately sought funding to support this inclusion of young people. The Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) has generously supported the planning for Aquí, and this includes some compensation for our Advisory Committee, including students. We’re also grateful to the Illinois Arts Council for supporting our summer 2022 intern cohort and Bank of America for supporting the cohorts of summer interns from 2023 to 2025. Paying students and young people is crucial to their ability to participate, and there are several students who could not participate even with the stipend because the Museum could not offer a full-time schedule or work beyond the summer months. The type of paid internship we’re offering is a baby step toward changing the overall pipeline of preparation for museum professionals so that we can truly diversify the field. We are absolutely thrilled to work with young people throughout this project, but we feel very humble about still not having the ability to overcome the barriers between some underserved young folks and work at CHM.

That being said, we’re proud of the internship program for Aquí. Following two small pilot cohorts in 2021 and 2022, the program will enable eight young people to work on the project for each of three summers leading up to the opening in October 2025. Our interns for 2023 have already been selected. One of the original goals of the students at Rudy/IJLA was always to build a movement of Latino/a/x youth across the city to work on the inclusion of Latino history in the history of the city. To that end, we will be seeking applicants for the program from around the metro area and bringing them together to create new research and programming at CHM. In summer 2023 and 2024, the interns will work with Curatorial Department staff, including me, to complete research projects on the topics of their choice within our storyline. They will write finished projects that will ultimately influence our label writing for the exhibition. Their choices of images and of objects may also make their way into the exhibition. In summer 2025, interns will be working with the Education Department on public programming to support the exhibition. This is a very important area because there are many topics that either cannot be addressed within the gallery because of space constraints or complexity. Programming is one of the ways in which the Museum becomes a forum for public conversations.

The second part of your question, about how I blend my academic and social justice practices into spaces such as CHM, is very important to me. It’s at the heart of my work. For me, the purpose of my academic research is to put it into practice. And my practice takes place in the space of the museum. For me, research and the theoretical concerns of academia are very utilitarian. I see them as tools to be used in our collaborative work for social justice. If we want to see the equitable distribution of risks and rewards in society, we need all of the available tools to make that happen. The museum—any museum, including CHM—is a venue where we can work to equitably distribute rewards such as representation. It is also a tool in and of itself that we can use to address inequities all throughout society by providing historical context and examples, powerful stories, and an examination of the effects of different strategies for creating change throughout history.

I was very impressed by your curatorial work in the recent exhibition you organized for the University Art Museum at New Mexico State University, Contemporary Ex-Votos: Devotion Beyond Medium. Even though social justice wasn’t necessarily mentioned in the introduction to the exhibition, it came out as a theme for me. How were you and your collaborators thinking about social justice as you shaped the exhibition? As you consider our various curatorial experiences and your students’ work on Crossroads, what are your hopes for your students? What are your hopes for the Crossroads exhibition and Aquí en Chicago?

Ortega: Thank you, Elena. This exhibition was a great effort from many people. This is the first time I put such a large show together. My main goal was to make this exhibition as collaborative as possible. In essence, Contemporary Ex-Votos sought to highlight the life of ex-votos from the nineteenth-century to the present. We commissioned fifteen artists to respond to NMSU’s collection. Ex-votos (for context) are votive paintings made by unknown artists throughout Mexico from the seventeenth century to the present. The process of creating one of these images was community based. The images sought to tell the story of a supplicant, their journey, and the ways they aimed to give gratitude to a specific saint and/or deity. Patrons worked alongside artists, and their placement in public Catholic sanctuaries opened a communal space of healing. It was precisely that communal process that we wanted to replicate.

I organized a class here at UIC where students interacted with students and staff from the NMSU art museum. We learned a lot from them, and together we made sense of the importance of this exhibition, and the opportunity it represented in changing the narrative surrounding the erasure of ex-votos from major art canonical texts and conversations. As such, the final product was the result of a collaboration between students, artists, museum staff, scholars, and myself. In fact, two of my PhD students ended up co-curating one of the galleries. Students from my class at UIC did a lot of research and worked on translating a lot of the text from the ex-votos. In the end, we curated three galleries, and many of the contemporary artists, with these communal ideas in mind, replicated the spaces of memory and healing needed to house new and old work. Working closely with all parties involved in this process, including artists, students, and museum professionals, was not only a different form of curating but a way of championing social justice. I feel we were very successful in including and educating many students, and, in the end, I hope we were able to redeem the complicated and tumultuous history behind the ways we have erased ex-votos from the larger history of art in Mexico. To me that is a form of social justice.

My hope for Aquí is similar. I loved the fact that social movements and organizing are the main factors driving your practice, Elena. I know this will be reflected in the final product. One of the issues behind many museums around the country is the fact that they pretend to reflect the needs of the communities they serve by way of curating. However, more often than not, museums are indebted to their institutional legacies and unweaving those historical patterns necessitates ongoing work. By introducing a new permanent exhibition via a dialogue between the Museum and the communities that it is meant to serve, you are already subverting these traditional legacies, this has the potential to create a model for many museums to follow. As museums around the country reckon with their historical collections and how to display them, Contemporary Ex-Votos exposed the power of new generations of artists, students, and scholars to scrutinize the material culture embedded with colonial violence. I think that Crossroads is doing something similar; reshaping the narrative that is told about the formation of the city, the labor, and the culture that maintains it.

With this in mind, how do you envision your process to have a larger impact in curatorial practices? Also, I’ll return the question back to you, what are your hopes for this exhibition and the role you want it to play in the communal memory of Latinx populations of Chicago?

Gonzales: If there’s one thing I can say about the process I’ve been going through with Aquí, and I think it extends to Crossroads as well, it’s that it is S-L-O-W. And that’s by design. That’s intentional. My hope in terms of influencing curatorial practices in general (if I could wave a magic wand) would be this: first, that all curators in all types of museums consider their projects in terms of how they could help better distribute risks and reward in society—how they could use their projects for social justice, especially in terms of environmental justice and antiracist work.

Secondly, though, we need to think about how to do this type of work. My experience from these and other projects is that it should be slow and careful work that privileges human interaction and sustainability (not rushing and getting burnt out in our work and racing on to the next thing). Giving ourselves time to make all the necessary connections to potential collaborators across many different communities is the bedrock of building respectful relationships and, therefore, having something meaningful to say. It is not respectful to come to someone last minute and ask them to jump on a project and do lots of work. I often talk about the word “curate” meaning “care” and all of the different types of care that goes into this work. The most important form of care in curatorial work is caring for people and other nonhuman life on this planet. That’s why we’re here in the first place. So, within that work of caring for people and building respectful relationships that allow communities’ stories to emerge in museum settings, I would say plan to take the time. The process is often the product.

Aquí is a great example of that. I’m so excited to actually open the exhibition—to be ready to open the exhibition. But the exhibition is not the purpose of the work we’re doing at CHM and with our partners. The purpose of the work is to build up the musculature of the relationship between CHM and the Latino/a/x third of the city so that CHM can be a respectful and trusted storyteller of the city as a whole—a storyteller that regularly includes stories about, by, and for these communities and many others. So, the exhibition, Aquí en Chicago, is one step on the way to building this relationship. Like decolonization, the process will never be complete. Like any relationship, it will need ongoing nurturing to flourish. But my hope is that after several years of sustained work on this specific project, during which we open Aquí, Latino populations around Chicago will begin to feel seen within Chicago history and will begin to feel that CHM is one worthy custodian of that communal memory for generations to come.

I also hope that the alumni from Rudy/IJLA who initiated this project and their peers have some of their questions answered about their communities’ histories and feel that CHM could be a welcoming place to begin further research into their areas of interest. The work we’re doing in Aquí is a microcosm of the much larger project we’re taking on with the planning for Crossroads. And it extends well beyond Latino communities of Chicago to build many more relationships and tell stories that cross cultural boundaries of all kinds to build an inclusive history of the city.

On behalf of the Museum, thank you and your students so much for engaging in this experiment in critical museum observation. We’re very fortunate to learn from their experiences in the Museum.

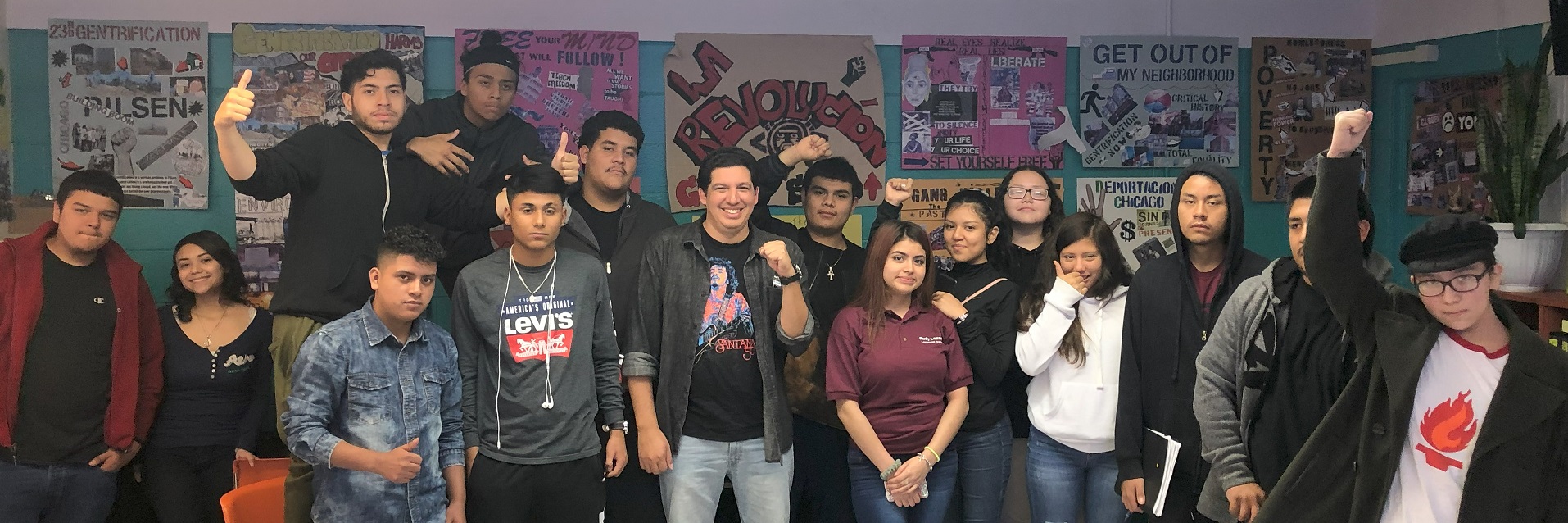

*Banner image of students from Rudy Lozano Leadership Academy (Instituto Justice Leadership Academy) courtesy of Anton Miglietta, Teacher, Instituto Justice Leadership Academy – Rudy Lozano Campus