To mark Saint Valentine’s Day, CHM reference librarian Maggie Cusick shares select valentines from our greeting card collection.

On February 15, 1872, the Chicago Tribune wrote: “Young maids and misses were yesterday anxiously hovering about the shops where valentines are sold, and bothering the postmen with inquiries after those that they thought they ought to get. Those who received were happy, and those who failed to receive lingered on in the faint hope that their tender missives must be lost in some corner of the Post Office, which would in due time give up its spoil.”

Chicagoans still looked forward to St. Valentine’s Day even just four months after the Great Chicago Fire.

Here at the Chicago History Museum, we have a collection of thousands of greeting cards from the 1840s to the 1990s that include cards for Christmas, birthdays, Easter, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, Thanksgiving, New Year’s, and yes, valentines—13 boxes of them.

This collection is a composite of many donations over time organized by subject and type. They fall into our category of “Prints and Photographs” and therefore can be served out to researchers in the Abakanowicz Research Center (ARC).

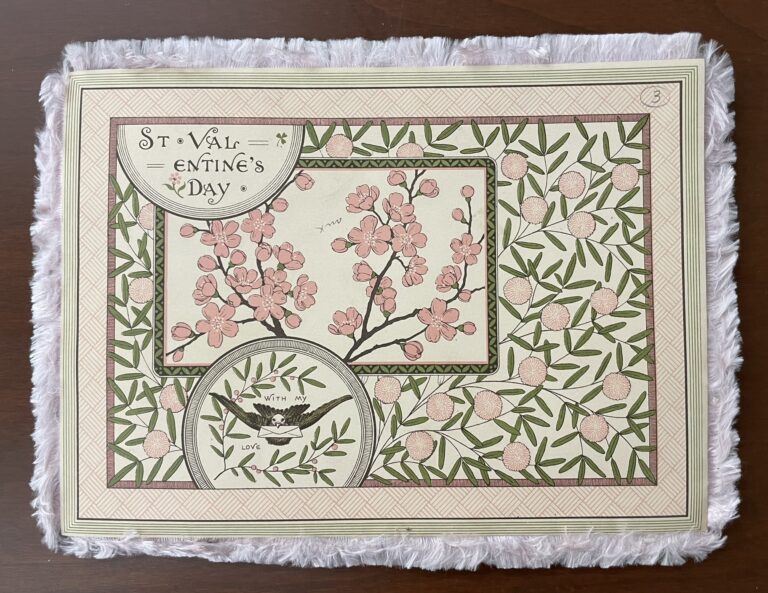

The valentines in the collection showcase the range of stylistic trends over time, and include wonderful handmade and homemade examples, and instances of addressed ones where we can maybe learn a little about the sender and receiver. They can be fun for those who are interested in many areas including design history, the history of ephemera, the history of correspondence, the depiction of relationships over time or the history of courtship, printing history, or specific artists or producers—such as Esther Howland, from New England, the first manufacturer of valentines in the US starting in the 1850s or Aveline Thorpe, working here in Chicago in the early 1900s—to name just two!

If you’re so inclined, please visit the ARC and peruse the flurry of lace, ribbons, satin, silk, paper, and gold foil, professing love—or disdain.

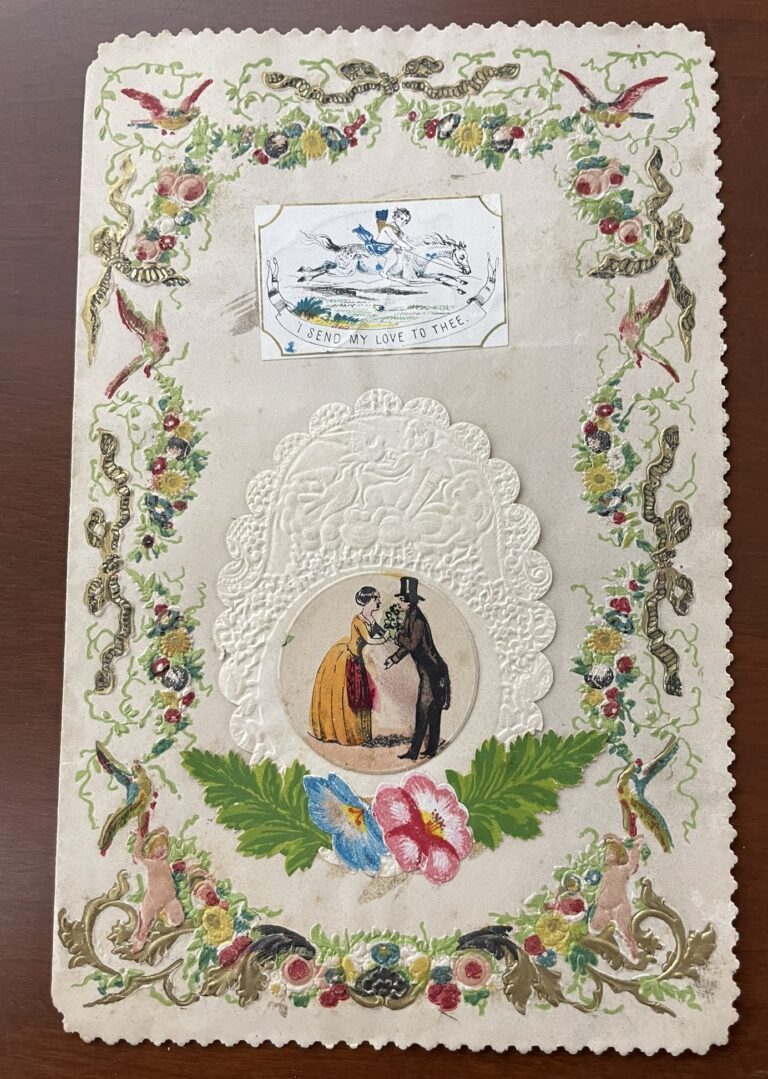

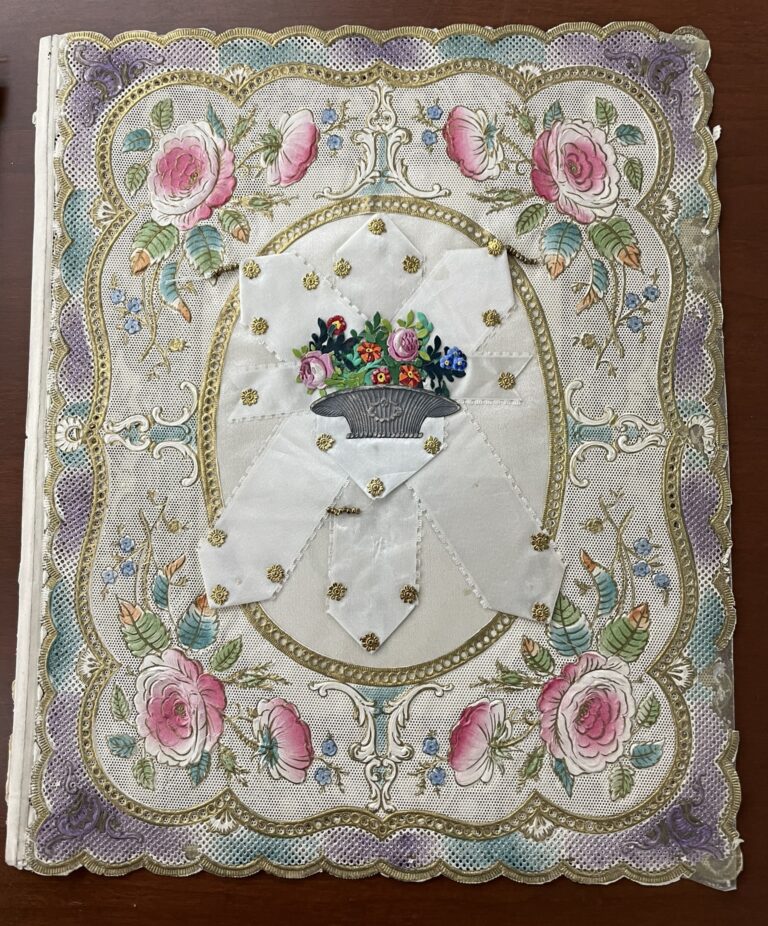

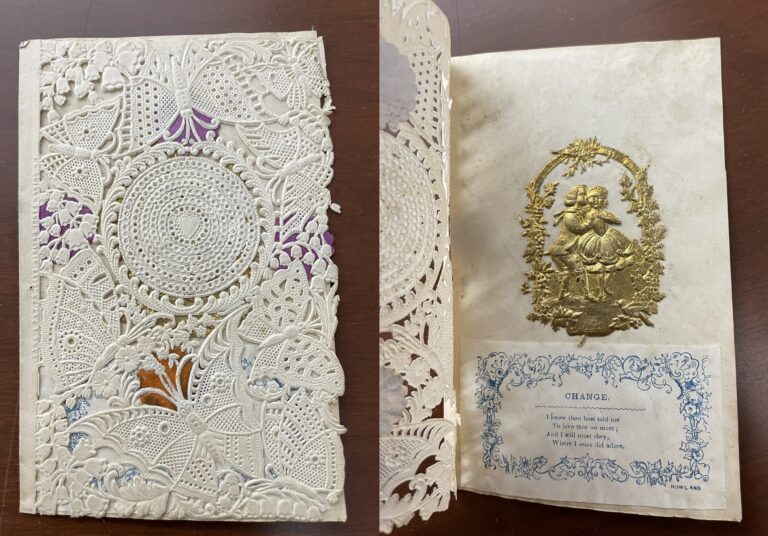

Early examples in the collection includes lacy and ornate cards from the mid 19th century that were typically found in bookshops and stationery stores such as Norris & Hyde, McNally, and E.L. Andrews. A Tribune reporter’s description said it was as if “engraver’s art had gone mad in the hands of some possessor” and “dainty and exquisite as if wrought by fairy fingers for fairy loves” (Chicago Tribune, February 15, 1859).

Esther Howland was the first manufacturer of valentines in the US, based out of Massachusetts. She began in the late 1840s after being inspired by an imported card. Her goal was to use embossed paper to look like lace. Above are two example of her work from our collection. Cards were being imported en masse to Chicago during that period—according to the Tribune, on January 14, 1859, “The largest stock of Valentines ever in Chicago is being received from New York by McNally & Co., 81 Dearborn street [sic]. Country dealers should by all means order from them, as by do doing they can be suited much better than by writing to New York.” This shipment possibly included some of Howland’s cards!

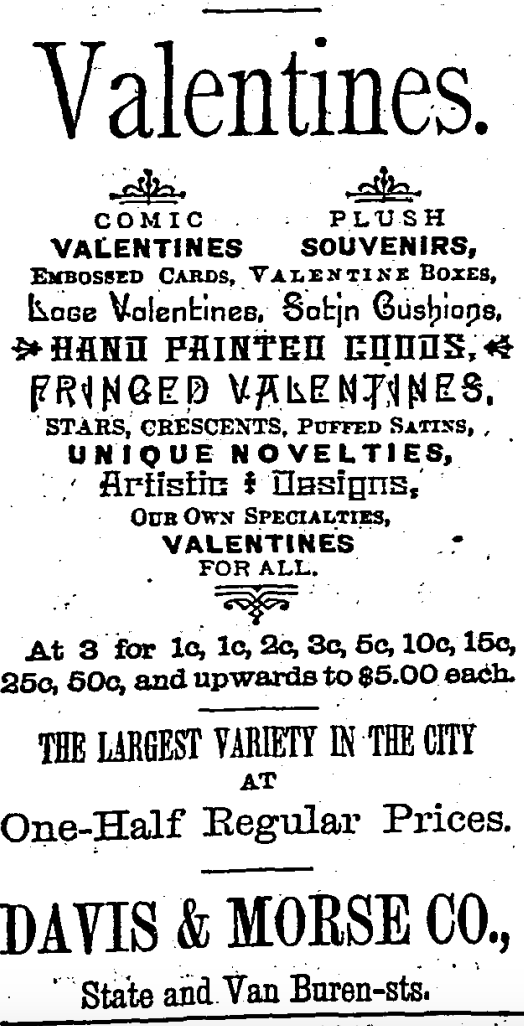

An advertisement for valentines in the Chicago Tribune, February 8, 1885.

In the 1880s, these “humorous and loving devices,” costing anywhere from 5¢ to $5, started to move away from the older style and saw a “card, large and small, modest in its adornment or elegant in its ornamentation,” and floral and landscape designs, pressed natural flowers, winter scenes, doves in a tree with verse, or fan shaped cards come into fashion. (Tribune, February 12, 1882)

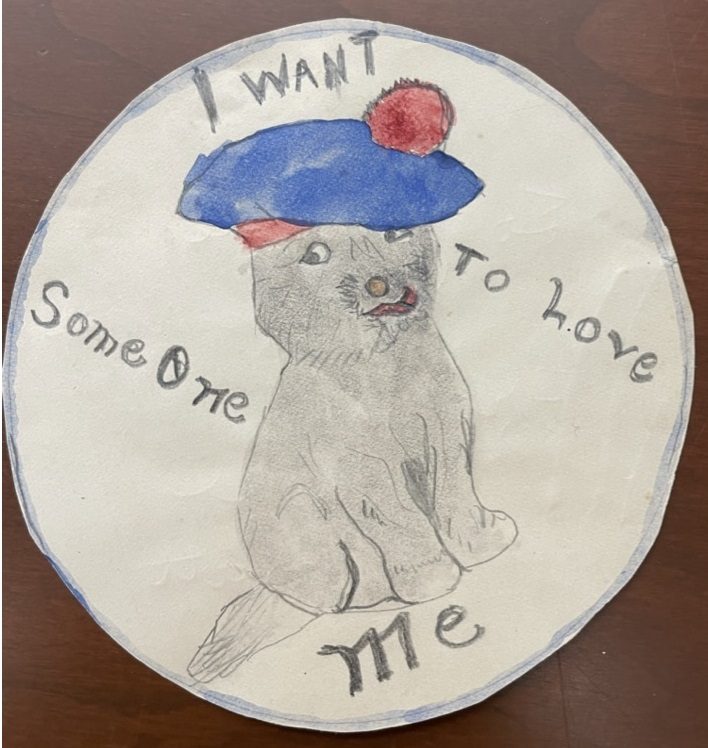

Before Esther Howland made valentines more affordable for Americans, in addition to importing them, many people made their own. We have some wonderful, whimsical examples of homemade cards in our collection.

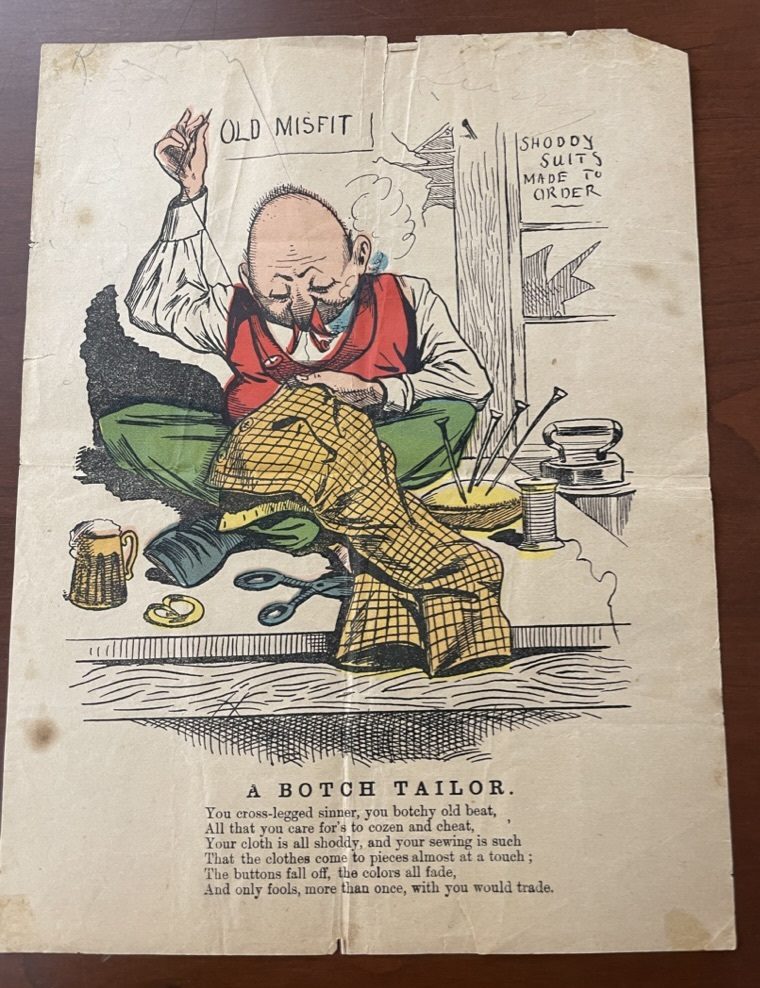

Common throughout this period was the “comic” valentine, sometimes known as the “penny dreadful” or a “vinegar valentine.” These were essentially mean cards, often with caricatures, that people would send to people they held a grudge or wanted to hurt—the original “trolling” perhaps! The Tribune wrote of a magazine illustrator named G. Howard who would create them when he was “out of humor and dissatisfied with life”! (Chicago Tribune, February 9, 1896).

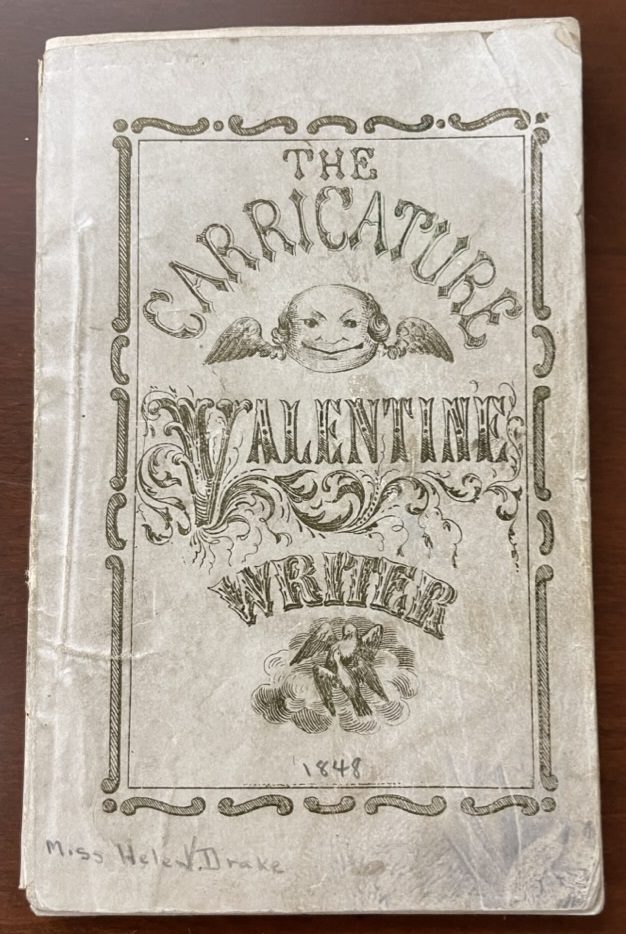

Above is a vinegar valentine about a tailor from the late 1800s and then a guide to writing these, published in New York in 1848, that provides prewritten verse to address any number of sorts of people.

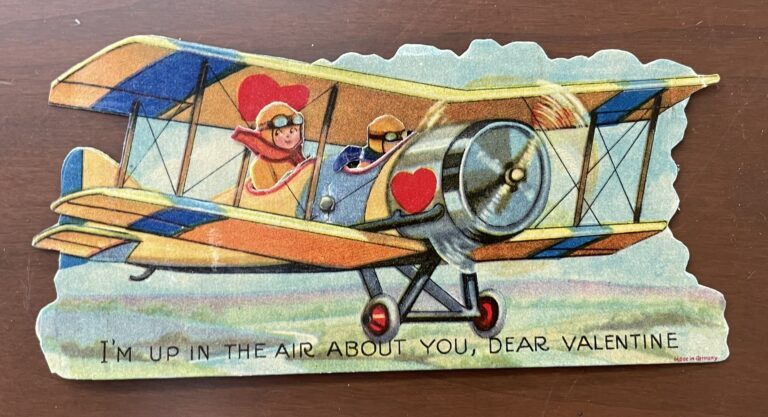

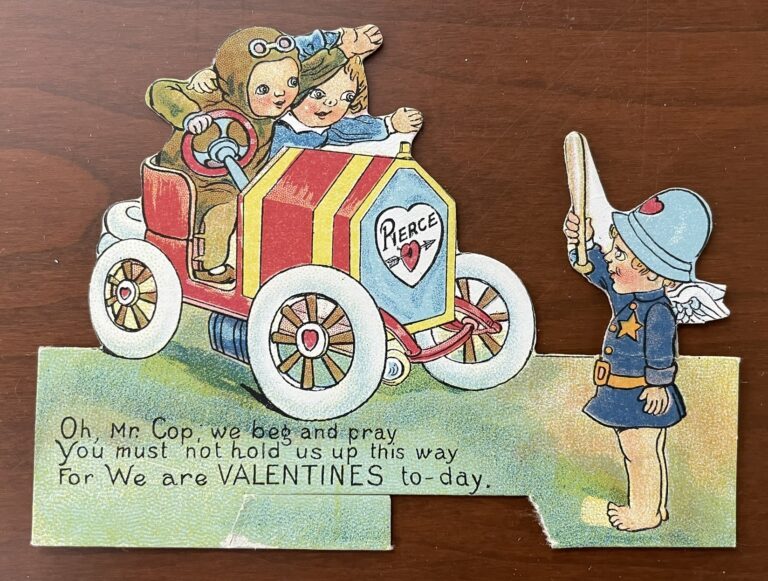

By the 1890s, the Tribune noted that bicycles, the “New Woman,” and other “modern” themes were appearing in valentine illustrations. How about motorcars, motorbikes, and airplanes? (Chicago Tribune, February 7, 1897)

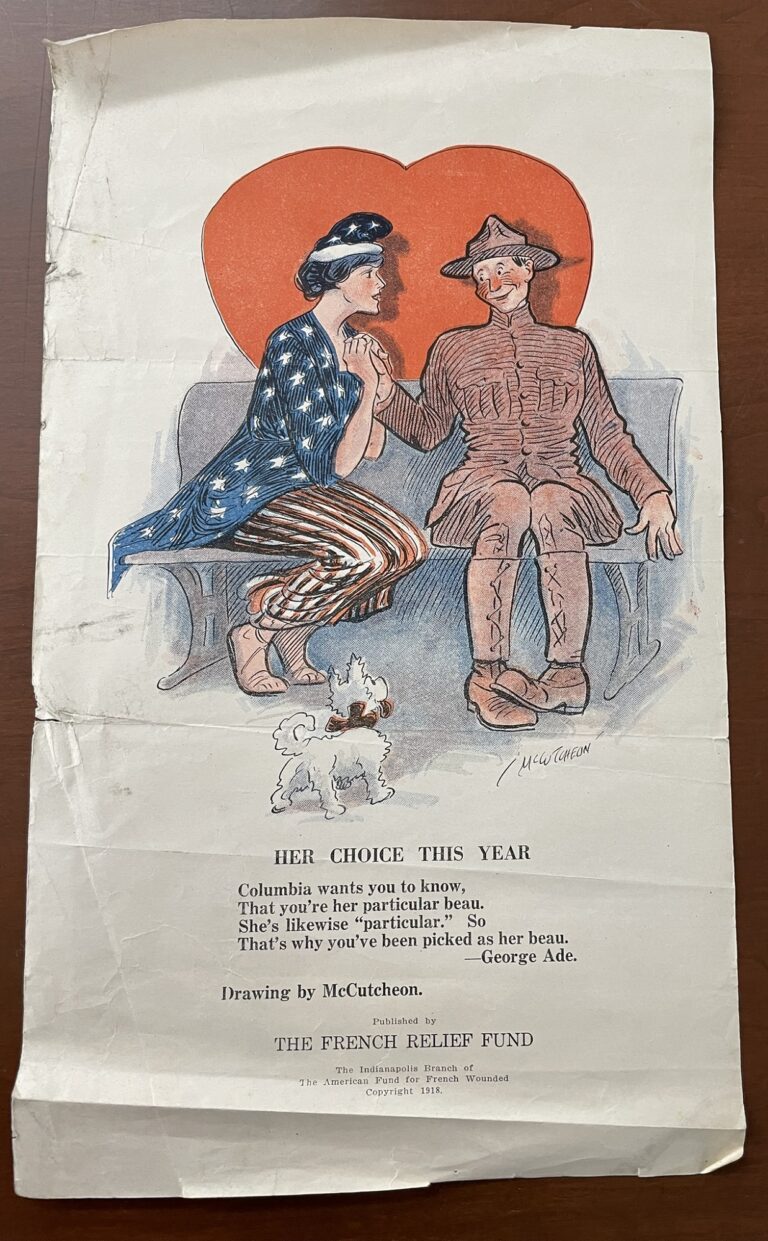

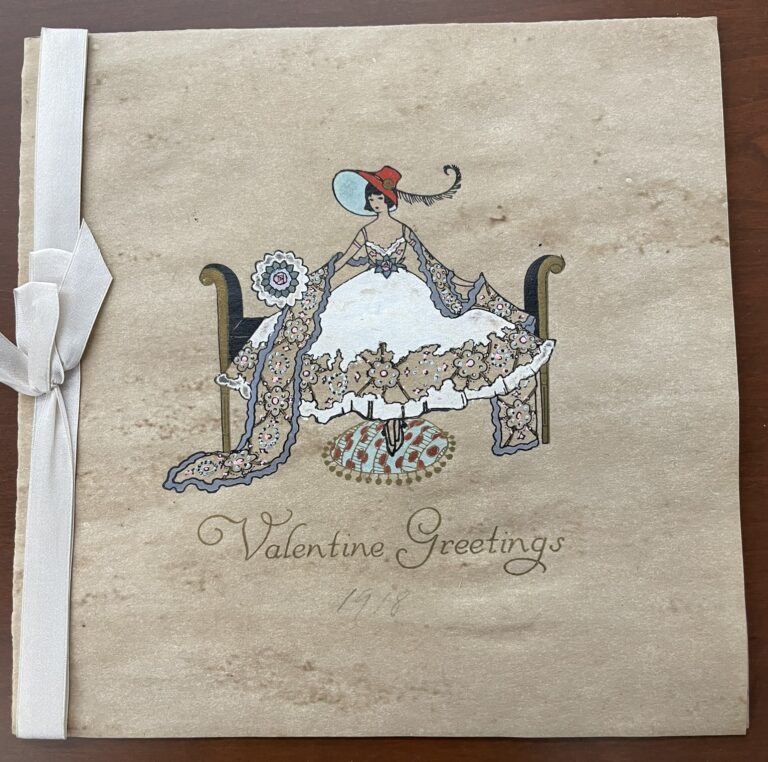

In our collection, there are two fabulous valentines from the 1910s—one that is clearly referencing World War I, and the other, with a handwritten “1918” in pencil, shows a woman in a short bob haircut, commenting on the old and new in verse, “Quaint and stately were the greetings sent by friends in days of old: just as true, sincere and tender are the thoughts my heart now holds.”

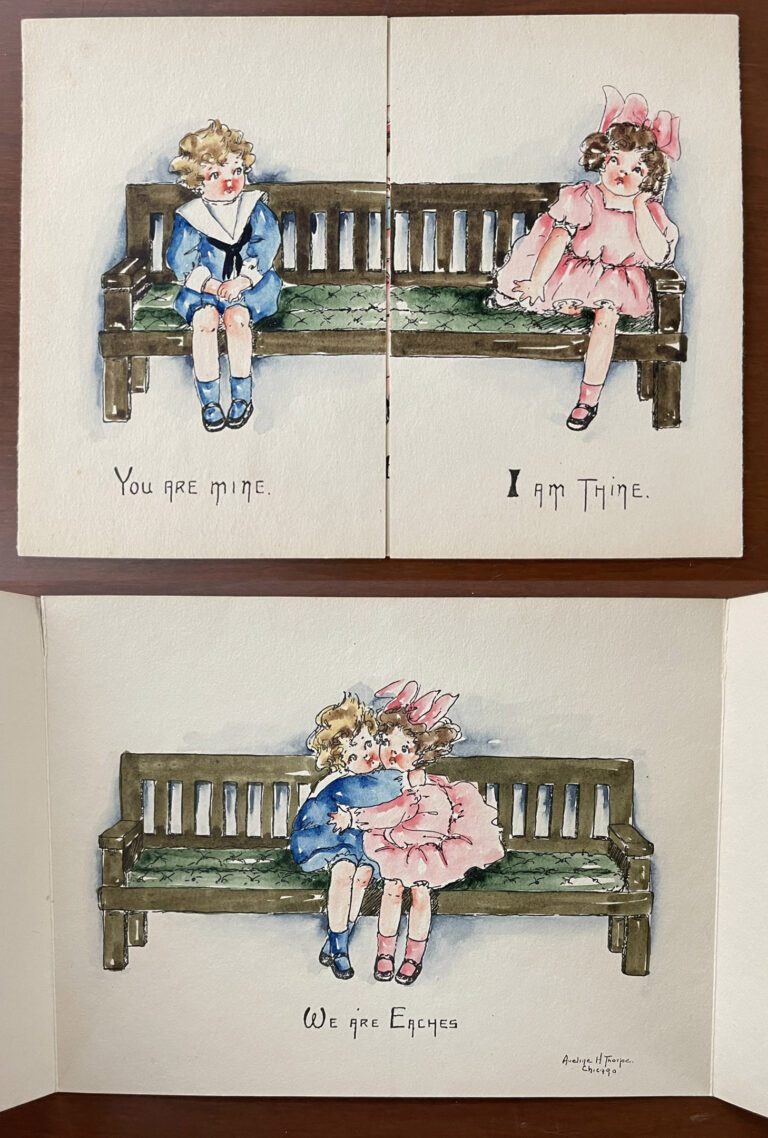

There’s another charming example from 1914 of a young girl and boy sitting on a bench, and the card opens to a sweet message. It also reads “Aveline H. Thorpe, Chicago.”

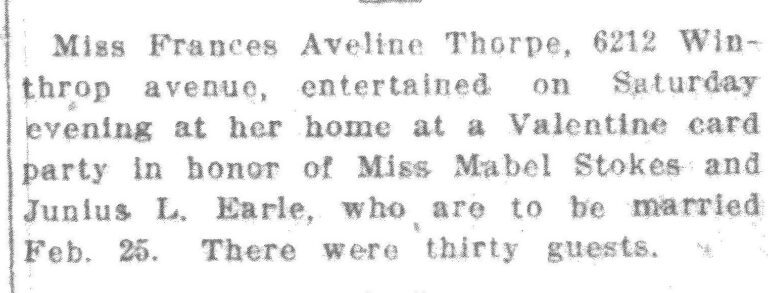

The name Aveline Thorpe shows up as someone involved with the Art Institute in the early 20th century and is listed in the 1923 directory as an artist living on North Winthrop Avenue. In the 1920 census, Frances Thorpe is listed as a commercial artist and her brother Homer as working in advertising for the Chicago Daily News, and in 1930, her brother James Jr. is listed as a salesman involved in engraving. In the Inter-Ocean paper, February 17, 1913, a Frances Aveline at that address held a valentine party at her home:

Frances’s mother is also Aveline (née Holman). It is unclear if this valentine was designed by mother or daughter. In the census, Aveline is not noted with a profession, but an Aveline Thorpe, designer, exhibited at the Art Institute in 1907—and Frances would only have been about 15 years old. Frances Aveline shows up later as a member of the Art Students’ League of Chicago in 1917.

From the 1920s through the 1950s, we start to see more of the cards we have become familiar with—printed, lots of bright colors, and hearts—and a now-household-name in the greeting card business—Hallmark!

Lastly, who doesn’t love cats and dogs for Valentine’s Day? Clearly, they have always been in fashion!

Additional Resources

- View the finding aid for our greeting card collection

- Learn more in Lester A. Weinrott, “Dear Valentine,” Chicago History (Winter 1974–1975):

- Read the Newberry Library’s blog post about vinegar valentines

- View the American Antiquarian Society’s online exhibition Victorian Valentines: Intimacy in the Industrial Age

- Read the American Antiquarian Society’s blog post on Esther Howland