In 1913, a sturdy brick and limestone building was completed and opened to the public; standing at five stories tall, what would come to be known as the Wabash Avenue YMCA was the result of community fundraising from area residents and the Chicago philanthropist Julius Rosenwald of Sears, Roebuck & Co. fame. While the building served as a job training center, temporary housing for stockyard workers, and of course a center for physical recreation in a segregated city, the Wabash YMCA’s most enduring legacy comes from its association with Dr. Carter G. Woodson.

Exterior view of YMCA of Metropolitan Chicago Wabash Avenue Building with addition in the Douglas community area of Chicago, c. 1940. CHM, ICHi-174453

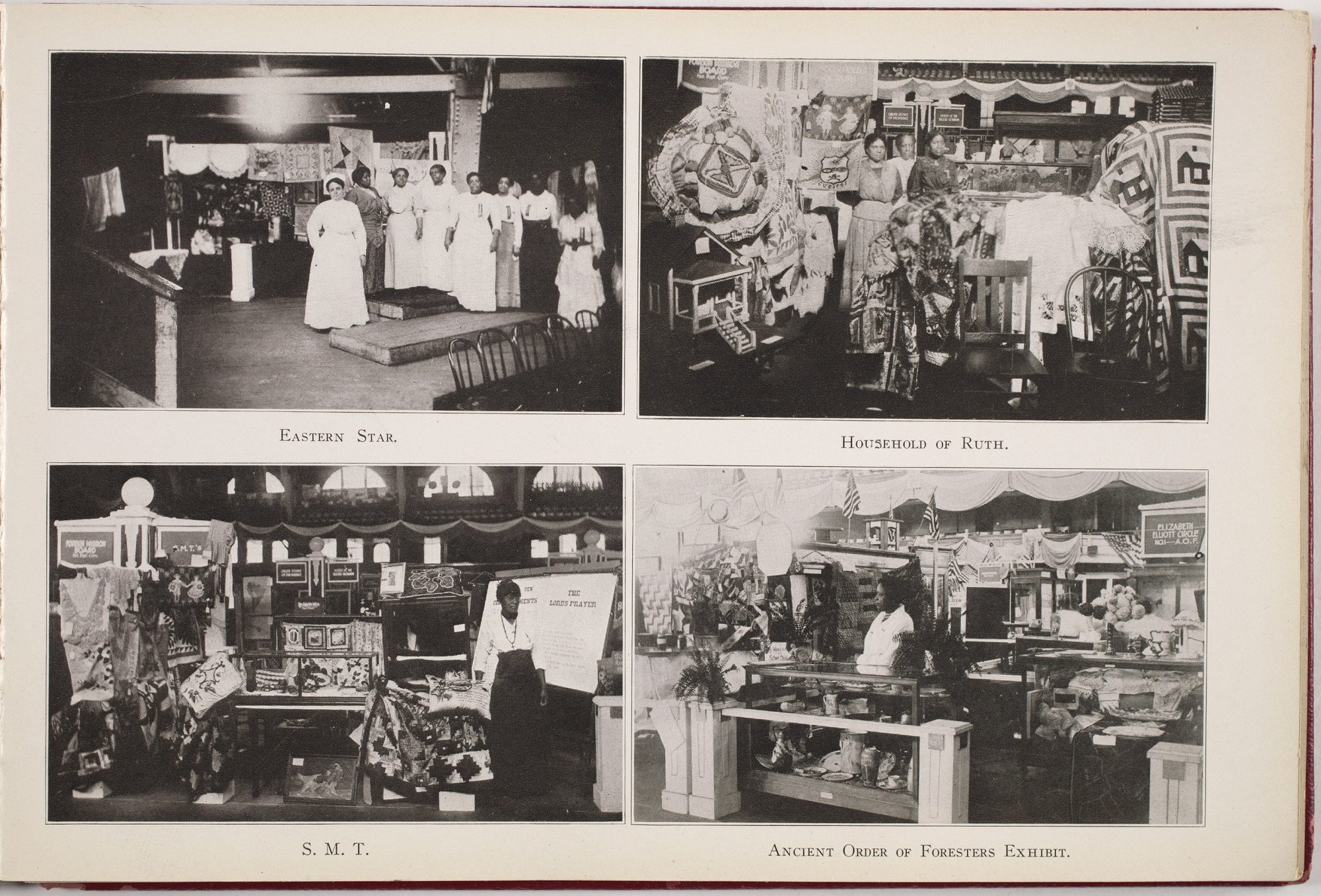

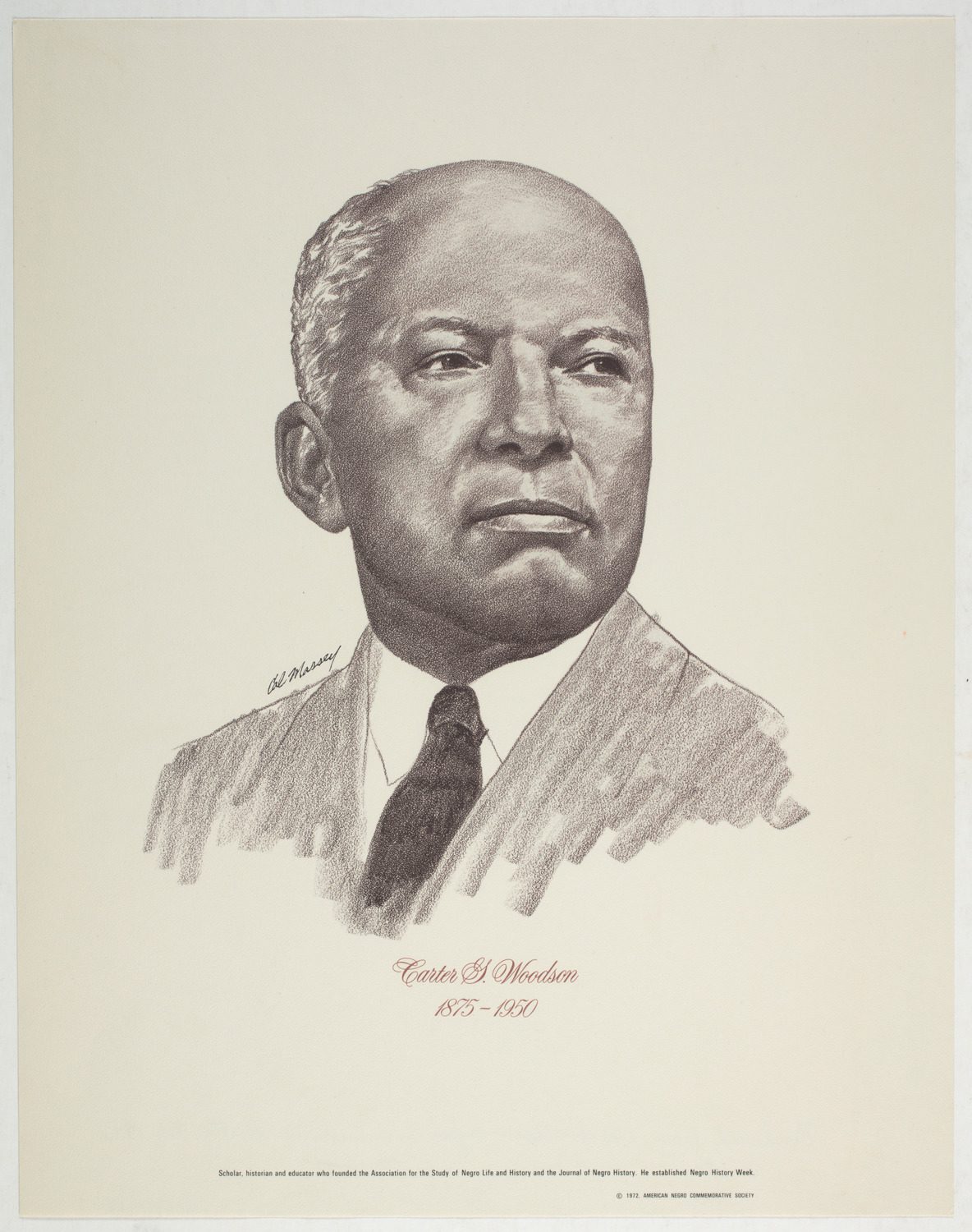

Born to formerly enslaved parents in 1875 in Virginia, Woodson would go on to graduate from the University of Chicago in Hyde Park and receive his doctorate in history at Harvard University in 1912. Three years later, in the summer of 1915, Woodson traveled to Illinois to attend the National Half Century Anniversary Exposition and The Lincoln Jubilee: 50th Anniversary Celebration. This exhibition in Chicago celebrated the semicentennial of the emancipation of enslaved African Americans in the US, highlighting the work and contributions to the nation by Black Americans across every aspect of society. In September of that year, Woodson convened a meeting with local leaders to form the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH, known today as the Association for the Study of African American Life and History) at the Wabash YMCA, with the goal of promoting Black history across Illinois and the US through educational programs and print materials.

Page featuring photographs (clockwise from top left) of the Eastern Star, Household of Ruth, S.M.T., and Ancient Order of Foresters Exhibit at the National Half Century Anniversary Exposition and Lincoln Jubilee, Coliseum, Chicago, August 22‒September 16, 1915. Published in the Lincoln Jubilee Album: 50th Anniversary of Our Emancipation, compiled by John H. Ballard, 1915. CHM, ICHi-174447; John H. Ballard, photographer

Portrait drawing, c. 1972, of Carter G. Woodson, scholar, historian, and educator. CHM, ICHi-031431; Cal Massey, artist © 1972 The American Negro Commemorative Society

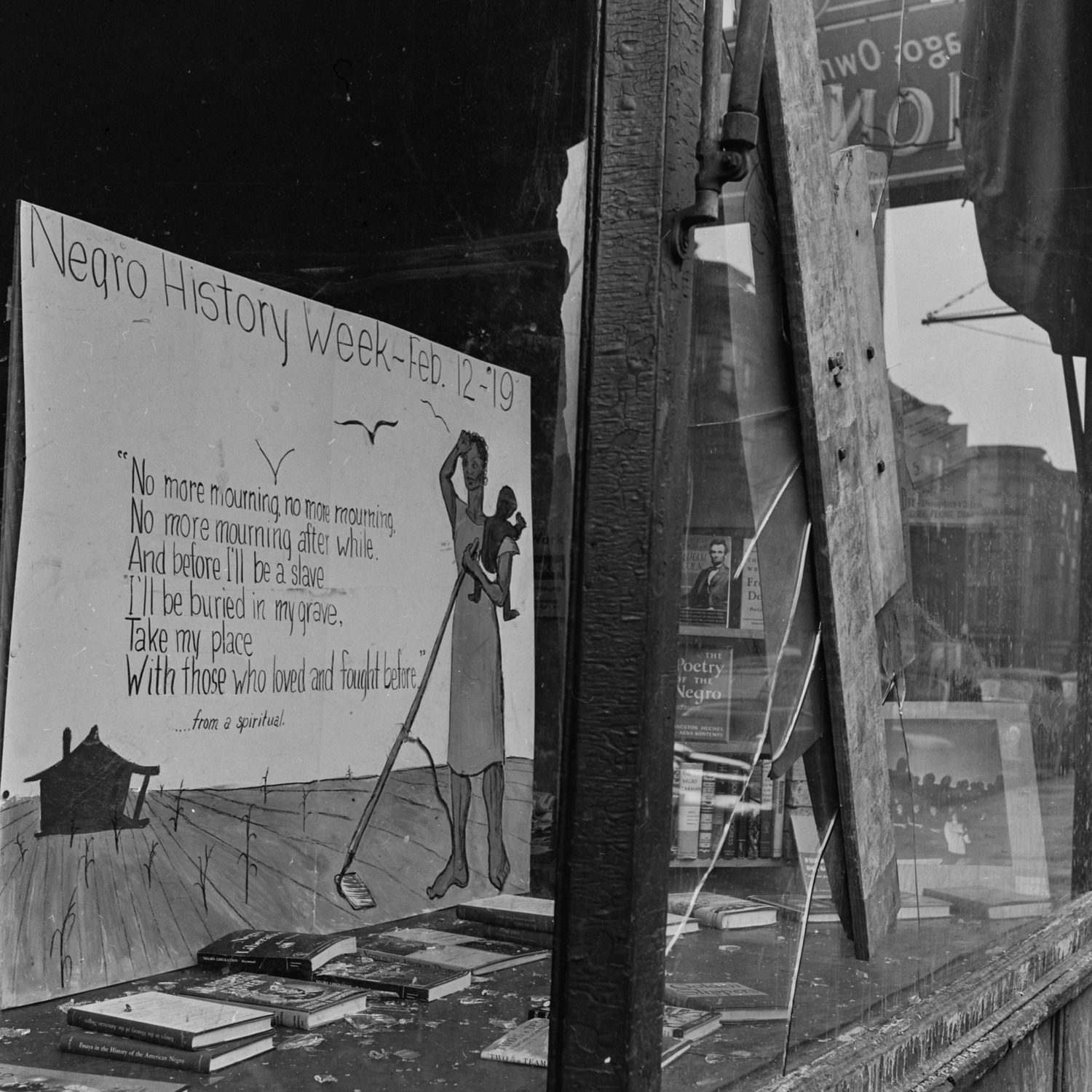

Black History Month had a number of other iterations before it was a month-long celebration. It began in 1924 as “Negro History and Literature Week” and then was renamed “Negro Achievement Week.” The third and final name change would come in 1926, when a press release came forward announcing the celebration of “Negro History Week.” Woodson’s History Week received much fanfare across the country, since, due to the Great Migration, population numbers for Black Americans boomed across urban areas in the US. This meant a desire to adopt Woodson’s teachings and mission into school curricula and social clubs.

Sign for “Negro History Week” in the storefront window of Community Book Shop owned by Joan Place at 1404 E. 55th St., in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago, February 1951. CHM, ICHi-087088; Mildred Mead, photographer

During all this movement, Chicago and the Wabash YMCA remained among the intellectual centers for Black History. Fortunately, the ASNLH counted among its ranks a Black librarian named Vivian G. Harsh, who worked for the Chicago Public Library system and who would eventually create one of the most robust archival Black history collections in the country, collecting books, ephemera, and other forms of cultural material related to the Black experience in the US. Harsh’s collection proved indispensable to the dissemination of knowledge for Woodson’s Negro History Week.

Woodson died following a heart attack in April 1950. He is interred at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Maryland. Twenty-five years after his passing, the Chicago Public Library system honored Woodson’s memory by opening a branch named after him on the South Side. This branch would also come to house the Vivian G. Harsh Collection of Afro-American History and Literature, ensuring that the collection and all its treasures would remain accessible to all those interested in Black history.

Federal recognition for Woodson’s celebration of Black history came a half century later, when during the 1976 celebration of the US Bicentennial, President Gerald R. Ford proclaimed every February to be designated as Black History Month. Ironically, Woodson hadn’t expected Black History Month to be a long-term observance, as he hoped Black history would simply be included as part of our national educational curriculum. The Wabash YMCA received its own recognition a decade later, when it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Today, the building is owned by The Renaissance Collaborative (TRC), a multifaith community organization that purchased the building while it was in a state of disrepair in the 1980s and, after a restoration, has turned the building into an affordable housing apartment complex, saving it from demolition.

Today, Black History Month is a national celebration that continues to honor the legacy of Black Americans and their contributions, whether scientific, cultural, or intellectual, to American society. While it serves as a time to look back and reflect on often complicated histories, it also offers an opportunity to reflect on possible futures.

Additional Resources

- Take a virtual tour of the Wabash YMCA

- Learn more about Chicago’s early Black populations in our two-part Google Arts & Culture project “Concert is Power”: Part 1 and Part 2.