This blog post has been adapted from an essay by CHM intern Megha Khemka, based on her work in the summer of 2022 focused on Chicago’s history with immigration.

Whatever your current picture of undocumented individuals, it’s probably incomplete. I know mine was. Immigration was a topic I thought I knew well; my parents were the first in their families to live outside of India. Yet the news I was reading around 2016—asylum requests systematically denied, detention centers lacking essential resources—was worlds away from anything I knew. Over the next few years, the material I saw grew denser and more polarized. It was only when I began researching the topic of sanctuary with the Chicago History Museum that I began to ask questions of my hometown and learned that Chicago has a lot of answers. To demonstrate, we’ll begin with a story that you perhaps have heard, the story of Elvira Arellano.

Arellano was born in Michoacán, Mexico, in 1975. She was 22 when she came to the United States. Thanks to Chicago’s sanctuary laws, she was able to build a life here with her US-born son, Saul, despite not having legal status. In the aftermath of 9/11, however, Islamophobia and xenophobia led public sentiment to associate immigrants with terrorists. After the passing of the USA PATRIOT Act, national authorities conducted extensive sweeps of all federal buildings. They arrested Arellano, who worked at O’Hare International Airport, and ordered her to appear before an immigration court. When she pointed out that deportation would separate her from her four-year-old, a US citizen, federal authorities responded that the only way she could be with her son was to uproot him to Mexico. It was a story that brought to light for many the United States’ citizenship and immigration policies.

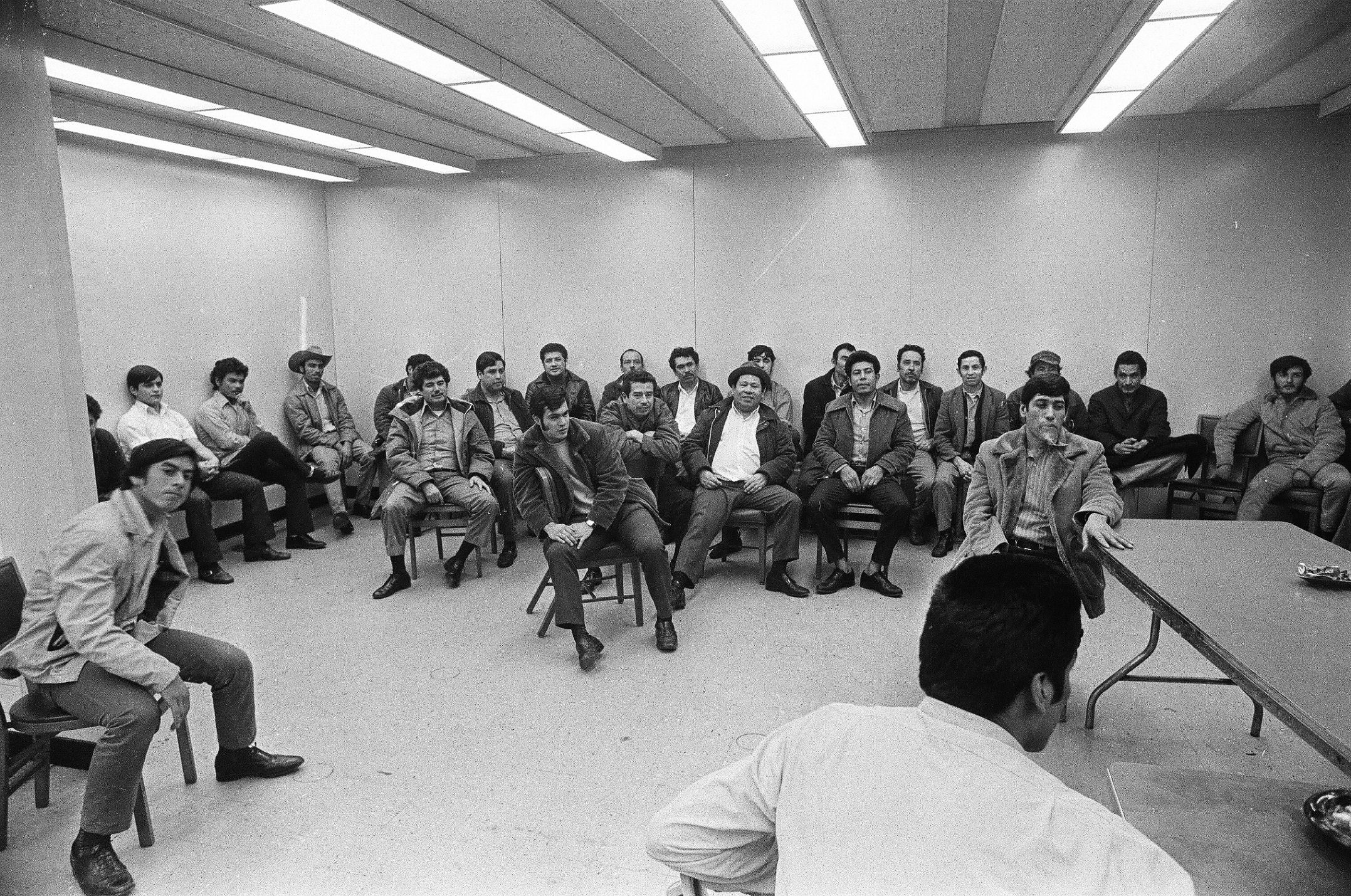

Undocumented immigrants of Central and South American descent sit in a room after being seized in a raid, Chicago, December 13, 1917. ST-10103912-0005, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The sanctuary movement in Chicago arose in the aftermath of civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala, funded in part by the US government, during which nearly one million refugees sought asylum in the United States between 1980 and 1991. Among those who had been killed in El Salvador were four US missionaries, and they became the face of a new organization: the Chicago Religious Task Force for Central America. It advocated for federal foreign policy changes toward Central America and encouraged domestic communities to host Central American refugees. In Chicago, they created a framework that connected undocumented immigrants with churches that were willing to provide them sanctuary.

A group of people gather in the Federal Building plaza to protest US aid to El Salvador’s military government during the Salvadoran Civil War, Chicago, February 7, 1982. ST-30002672-0027, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Bob Black

The idea quickly took hold, and in 1982, the congregation of Chicago’s Wellington Avenue Church voted to become America’s second sanctuary church. Over the next decade, 20 religious institutions in and around Chicago became sanctuaries, housing undocumented refugees and providing them with platforms—for example, venues for public press conferences and Bible study discussions—to make their stories heard. Participants were Christian, Quaker, and Jewish, creating a vast network of unsanctioned support.

A group of people gather in the Federal Building plaza to protest US aid to El Salvador’s military government during the Salvadoran Civil War, Chicago, February 7, 1982.ST-30002672-0042, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Bob Black

In my research, I discovered the impact of hundreds of diverse Chicagoans united in their belief. Even those who were hesitant to speak out enabled more vocal voices through their support. Adriana Portillo-Bartow’s two daughters were kidnapped in Guatemala, and after escaping civil conflict by moving to Chicago, she tirelessly campaigned the government, Catholic Church, and media to find her girls. Similarly, diverse coalitions came together in the election of Chicago’s first African American mayor, Harold Washington, who codified social support into law with Executive Order 85-1, written to “assure that all residents of the City of Chicago, regardless of nationality or citizenship, shall have fair and equal access to municipal benefits, opportunities and service.” This has formed the basis for Chicago’s legal protection of undocumented immigrants ever since.

However, a series of cases known as the Sanctuary Trials highlighted the lack of such legal protection on a federal scale. In 1986, the Justice Department indicted 16 individuals on 71 counts of conspiracy and of aiding “illegal aliens to enter the United States by shielding, harboring and transporting them.” Though the defendants argued that providing refuge was an expression of religious belief and therefore protected by the First Amendment, this argument was struck down by courts. Undocumented immigrants taking refuge in a religious institution are not immune from deportation. The protection that a sanctuary church offers is entirely social, based on the reluctance of any authority to order a raid on a religious building. Nevertheless, public support had power in the Sanctuary Trials, leading Congress to grant asylum to most of the individuals involved, illustrating the power of media narratives and community protest.

With that in mind, we return to Elvira Arellano, who until 2002 had been living quietly in America, trying to avoid deportation. After she was arrested, Arellano made a pivotal decision: she took refuge in Humboldt Park’s Adalberto United Methodist Church in 2006 on the date of her immigration hearing. She lived there for more than a year, eventually being deported while traveling to speak at a Los Angeles church. Her son remained at his home in the US, while Arellano continued to advocate tirelessly from Mexico. In March 2014, she presented herself to US Border Patrol officials at the San Diego border to request asylum.

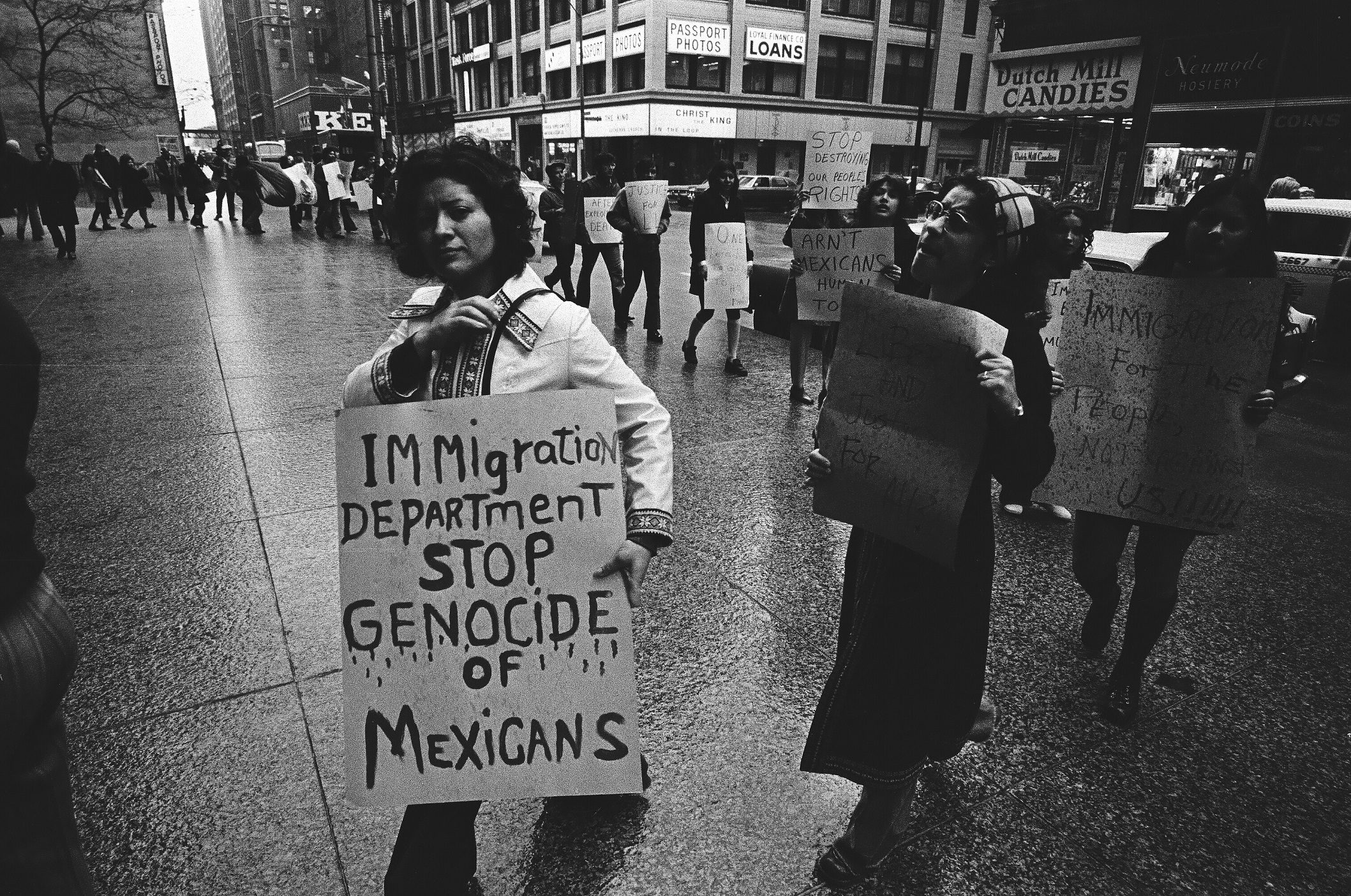

Protest at the Federal Building, 230 South Dearborn Street, over shooting of undocumented Mexican immigrant, Chicago, November 10, 1972. ST-14002237-0004, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Arellano’s story quickly began to gain national attention; as a powerful mother figure fighting to be with her American son, she was the perfect face of a new Sanctuary Movement. And it worked. Legal change at all levels of government followed during this time, including in Cook County, which passed an ordinance refusing to fill federal detainer requests for those suspected of being in America without a visa. However, the national buzz around Arellano’s story created a narrowly defined narrative of undocumented individuals in America that tied their right to stay in the country with the fact that they grew up here or had a child who did.

For instance, the Obama administration’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy allows undocumented individuals who came to the US as children to apply for deportation deferrals every two years. While the executive order benefited thousands of Chicagoans, Arellano herself argued that it didn’t go nearly far enough, only providing temporary relief for a very select group of people.

After the sustained efforts of a diverse coalition of Chicagoans, Chicago today is has one of the most comprehensive legal systems in place to support undocumented immigrants. The city’s population fought to preserve their deeply-held values of sanctuary even under pushback from Illinois governor Bruce Rauner, and Chicago’s lawsuit against the Department of Justice in 2017 is what has ensured that sanctuary cities all over the country are legally entitled to federal funding.

Yet, Chicago’s stories also remind us that sympathetic legislation does not mean the work for asylum seeker and undocumented individuals is done.