Latest Posts

In part two of this series, project cataloger Emma Florio explains more about the process of cataloging collections from scratch and the detective work it requires. Learn more about this retroconversion project, which was funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

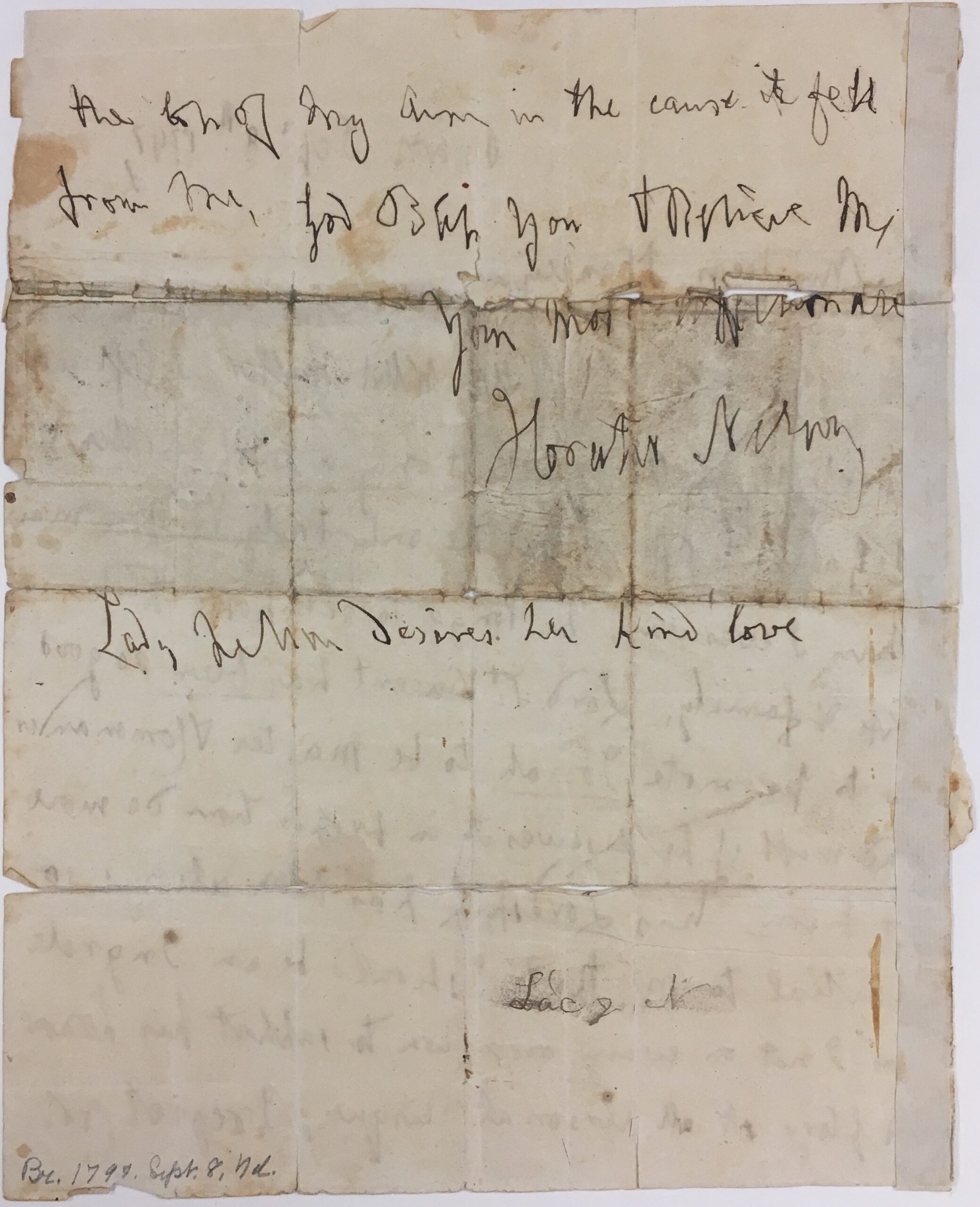

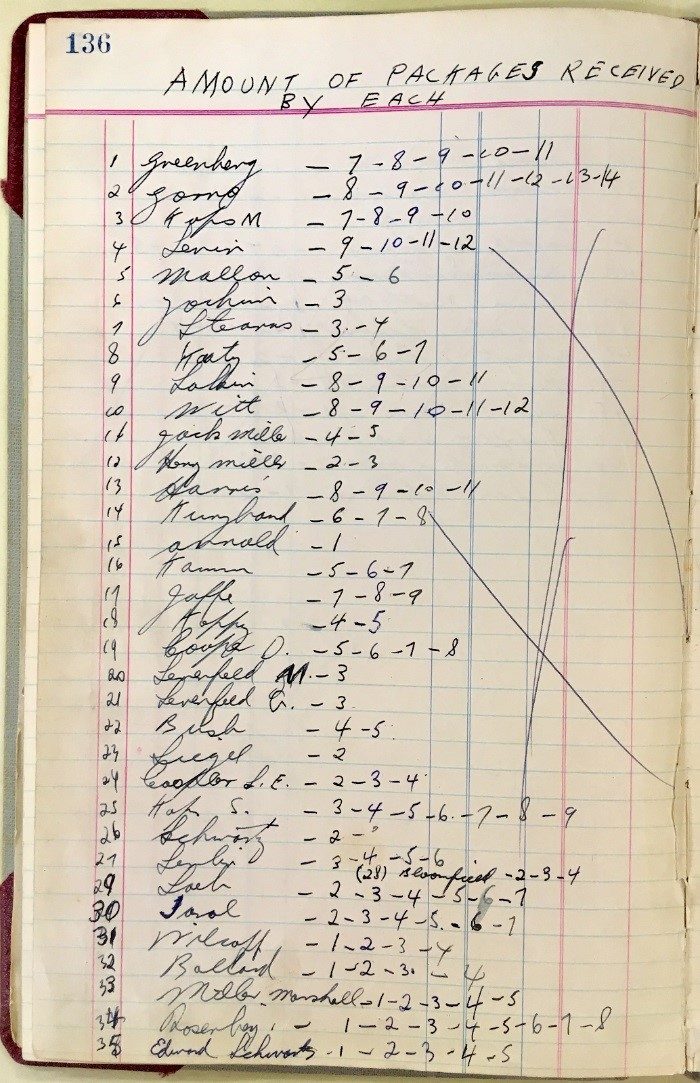

While digitizing the catalog cards for the Chicago History Museum’s small manuscript collections, I have seen a wide range of materials: eighteenth century documents from Spain certifying the bearer does not have the plague; records kept by a woman in Chicago of every man on her street serving in World War II and the packages she sent to them; a letter written by British Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson after losing his arm in battle; and the school work and sewing sample book of a young German girl living in Chicago in the early twentieth century.

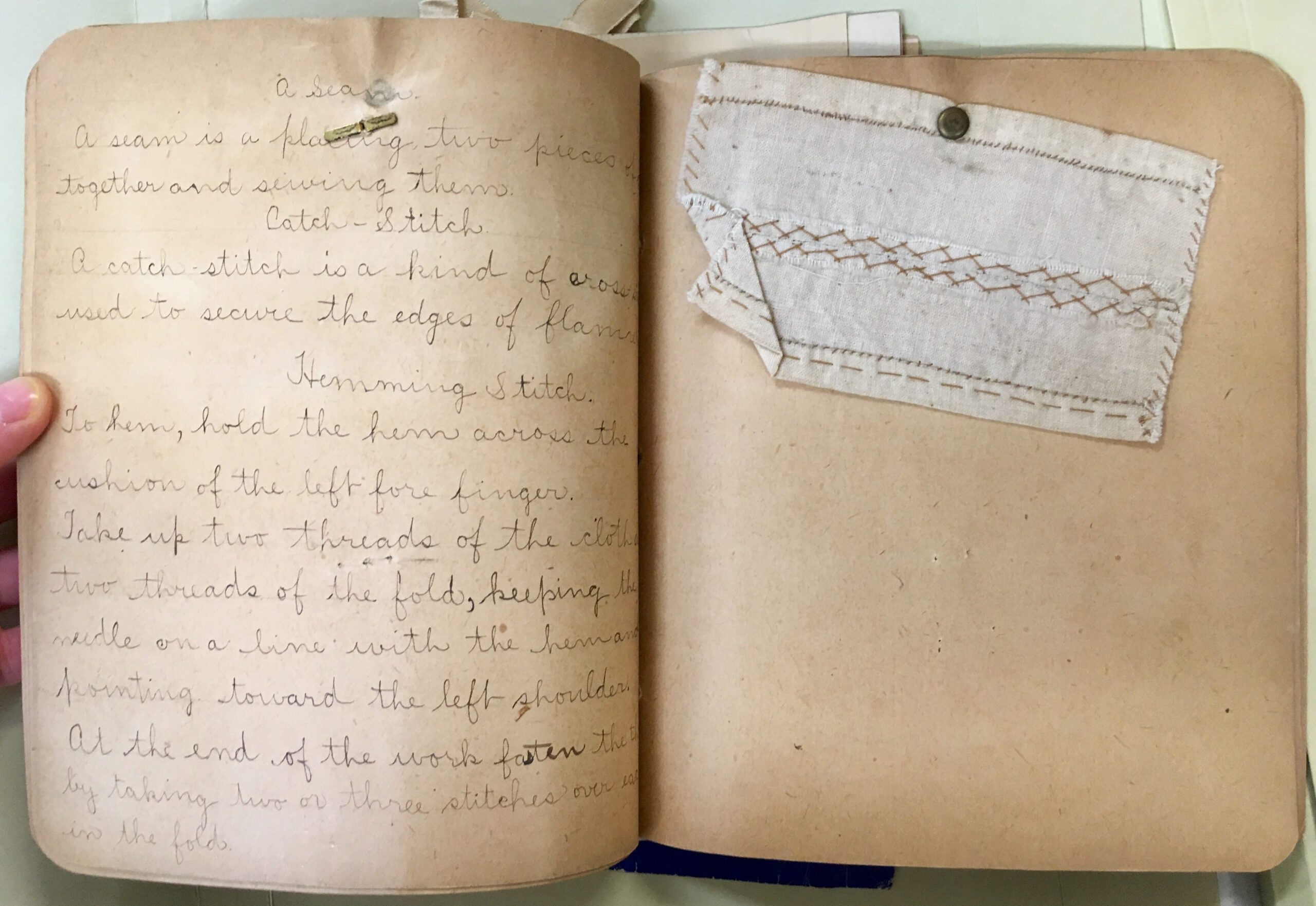

Sewing sample and school workbook of Gertie Maul, early twentieth century. Gertie Maul papers. All images by CHM staff

At the outset, this project was intended to involve working only in spreadsheets and computer databases, transcribing catalog cards, and editing that information for our digital catalog, ARCHIE. However, after processing several hundred collections, we realized that many did not have catalog cards and would need to be newly cataloged with the “item in hand” and described to make them easily discoverable to researchers, the same way it has been done for decades with the other collections in the card catalog.

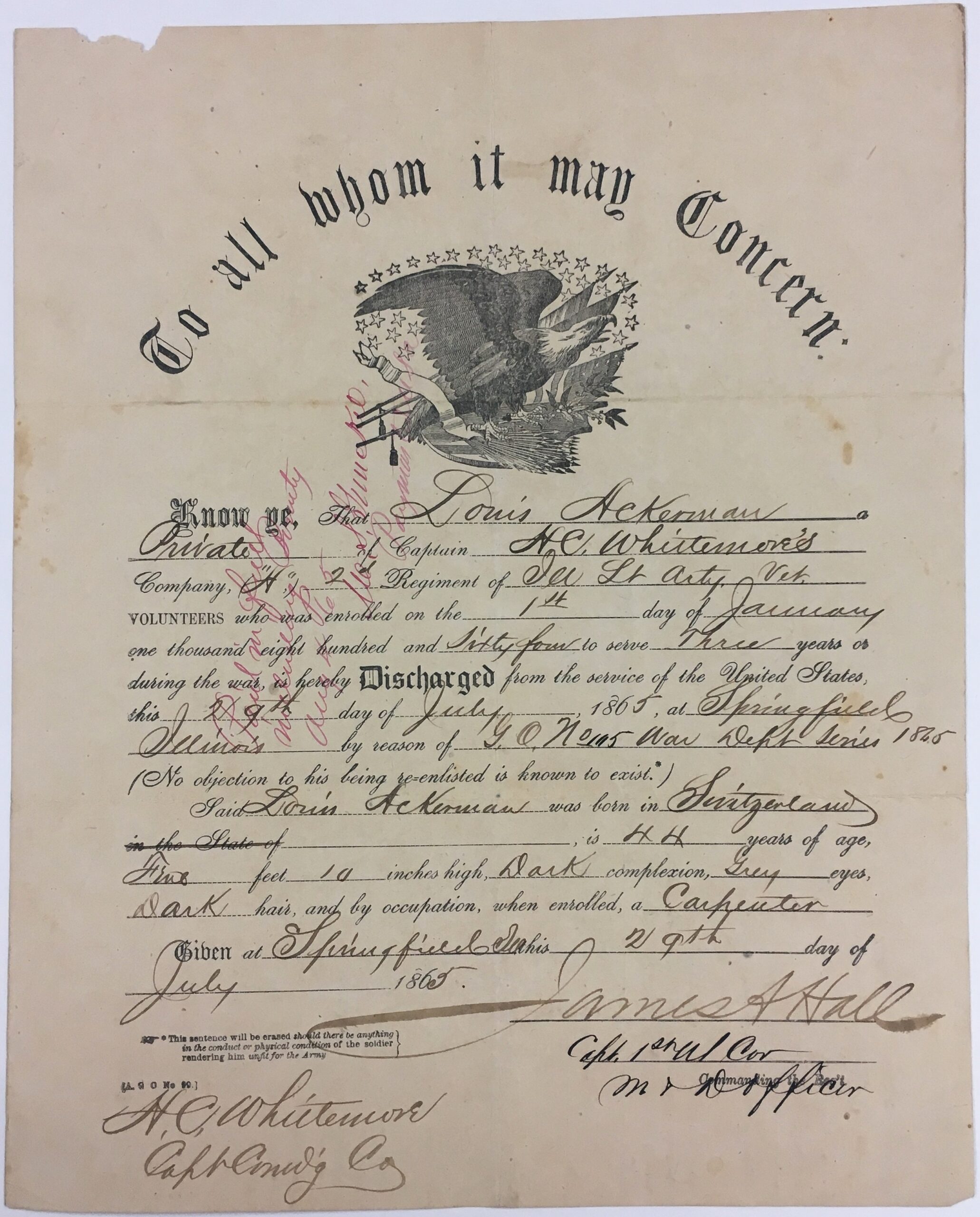

The honorable discharge papers for Louis Ackerman, a Swiss immigrant who lived in Chicago and fought in the Civil War. Louis Ackerman papers

Having the existing catalog cards and entries in Excel helped act as a guide when cataloging things from scratch. Usually, transcribing the date, name of the creator, location of creation, and other basic facts is a straightforward and quick process, though it can take some creativity to briefly describe or summarize some items. Assigning subject headings can often be the most subjective part of the process, by choosing which topics covered by an item will be of the most use and relevance to researchers.

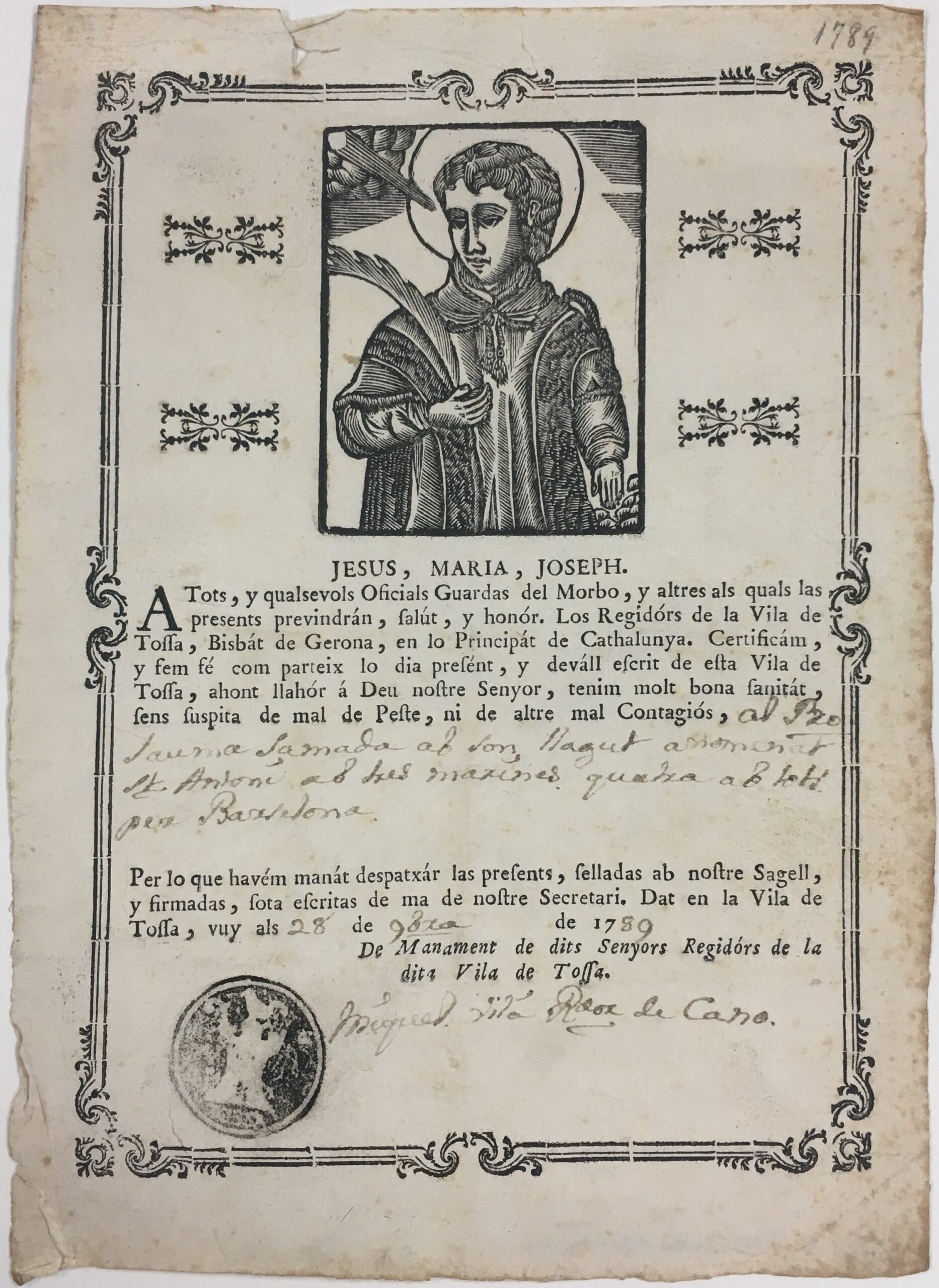

Categorized as a “medical certificate,” this document from Tossa, Catalonia, Spain, in 1789, certifies that the bearer does not have the plague. Medical certificates 1747–1802

After looking at nearly seven hundred collections that range from the seventeenth to twentieth centuries, I have learned that cataloging archival material can sometimes be like detective work. One difficulty I encountered was reading a wide range of handwriting, from neat and uniform to almost completely illegible; it can feel like a great accomplishment when you finally decipher a word that seemed like a bunch of squiggles just moments before. And opening a folder and seeing a typed letter or document always brings a sigh of relief. Also, sometimes items have almost no context other than the signature of the writer, which may just be initials and perhaps the city in which they live. Often a small bit of research on the internet helps solve the mystery. From simply reading a letter or document and needing thirty seconds to describe it to taking ten minutes to decipher and research an item, I have encountered many levels of difficulty in manuscript description.

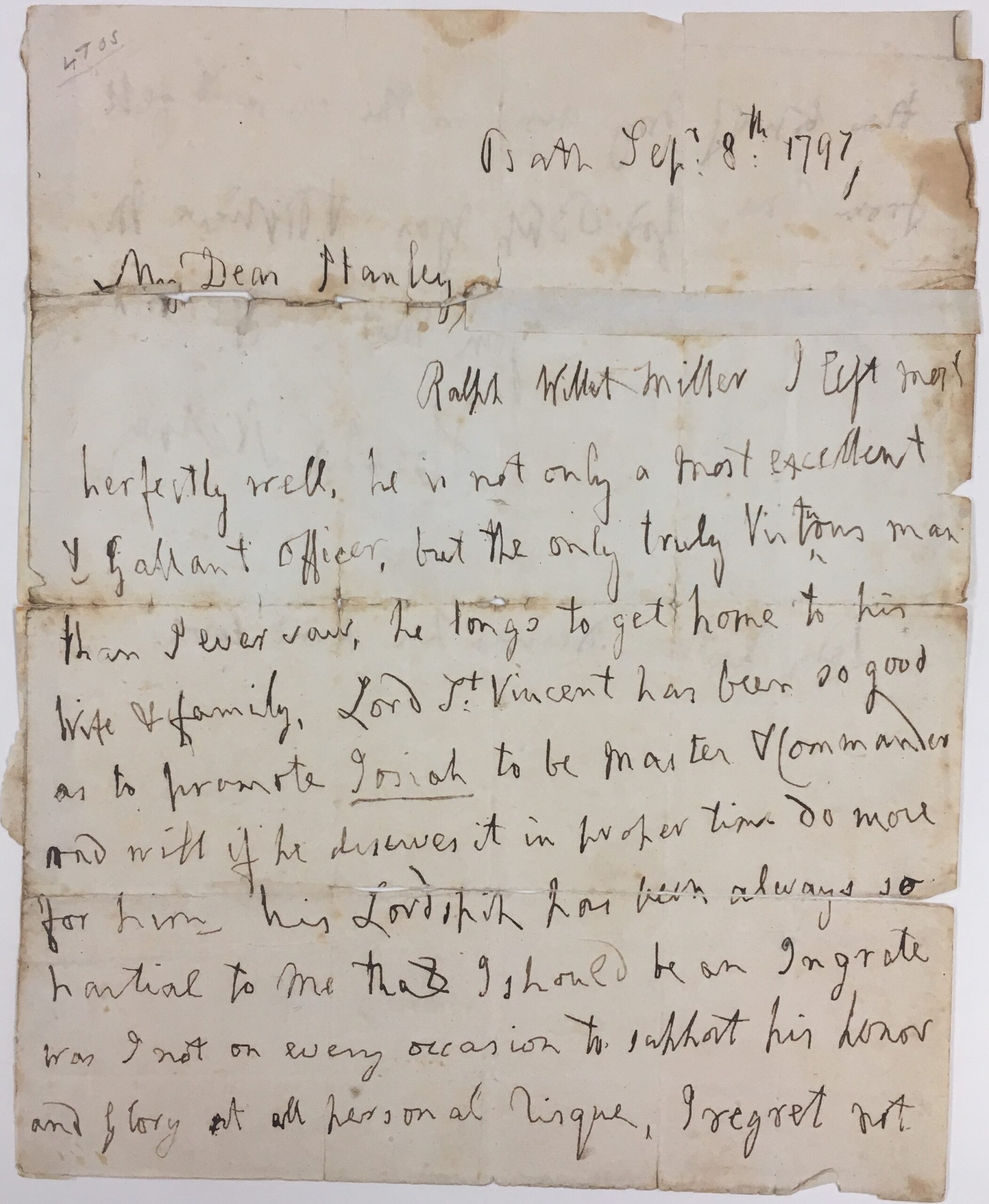

Letter written by Horatio Nelson on September 8, 1797, less than two months after losing his arm at the Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Horatio Nelson papers

List of soldiers who lived in Chicago during World War II and the packages sent to each by Sylvia Hornstein and her husband. Sylvia Hornstein papers

Overall, this project has been very rewarding and often exciting—you never know what you will encounter when you open the next folder to catalog it. From a single-sentence letter accepting an invitation to dinner to a multifolder collection of business correspondence, and everything in between, each collection in CHM’s Research Center tells a story that helps contribute to Chicago, American, and world history.

In part one of this series, project cataloger Emma Florio discusses the process of retroconverting CHM’s small manuscripts collections from catalog cards to digital records. Learn more about her work, which was funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

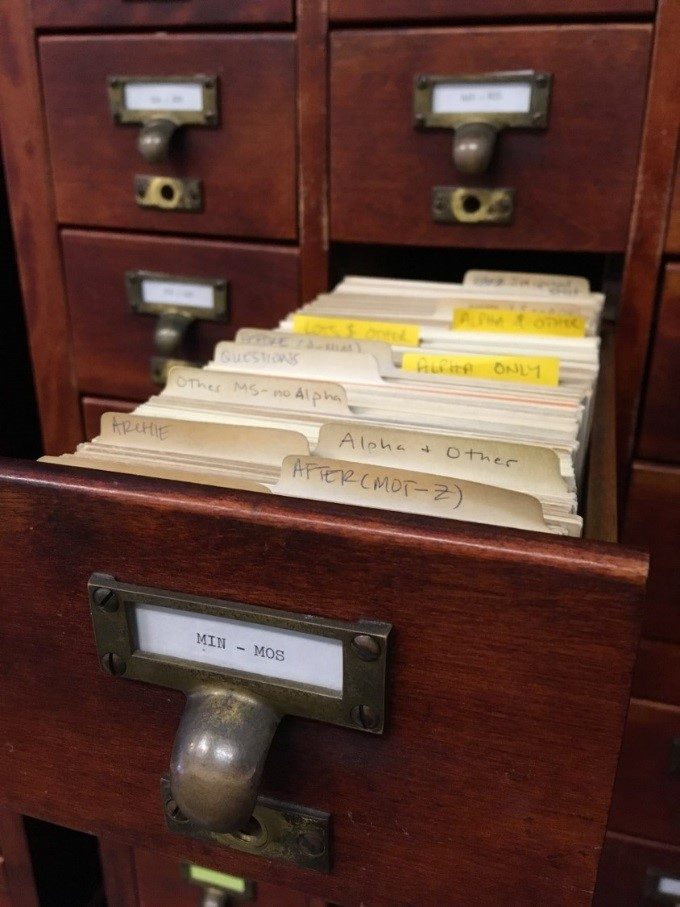

When I took on this project last summer, the Museum was in the final stage of digitizing the last of its paper card catalog for six thousand small manuscript collections. This involved editing or creating information for these collections, which range in size from a single letter in one folder to dozens of business papers, letters, and receipts spread across multiple folders. The goal was to make each one more accessible and discoverable in ARCHIE, CHM’s online catalog, as well as other library and museum databases, such as WorldCat and the Explore Chicago Collections.

The card catalog in the CHM Research Center. All images by CHM staff.

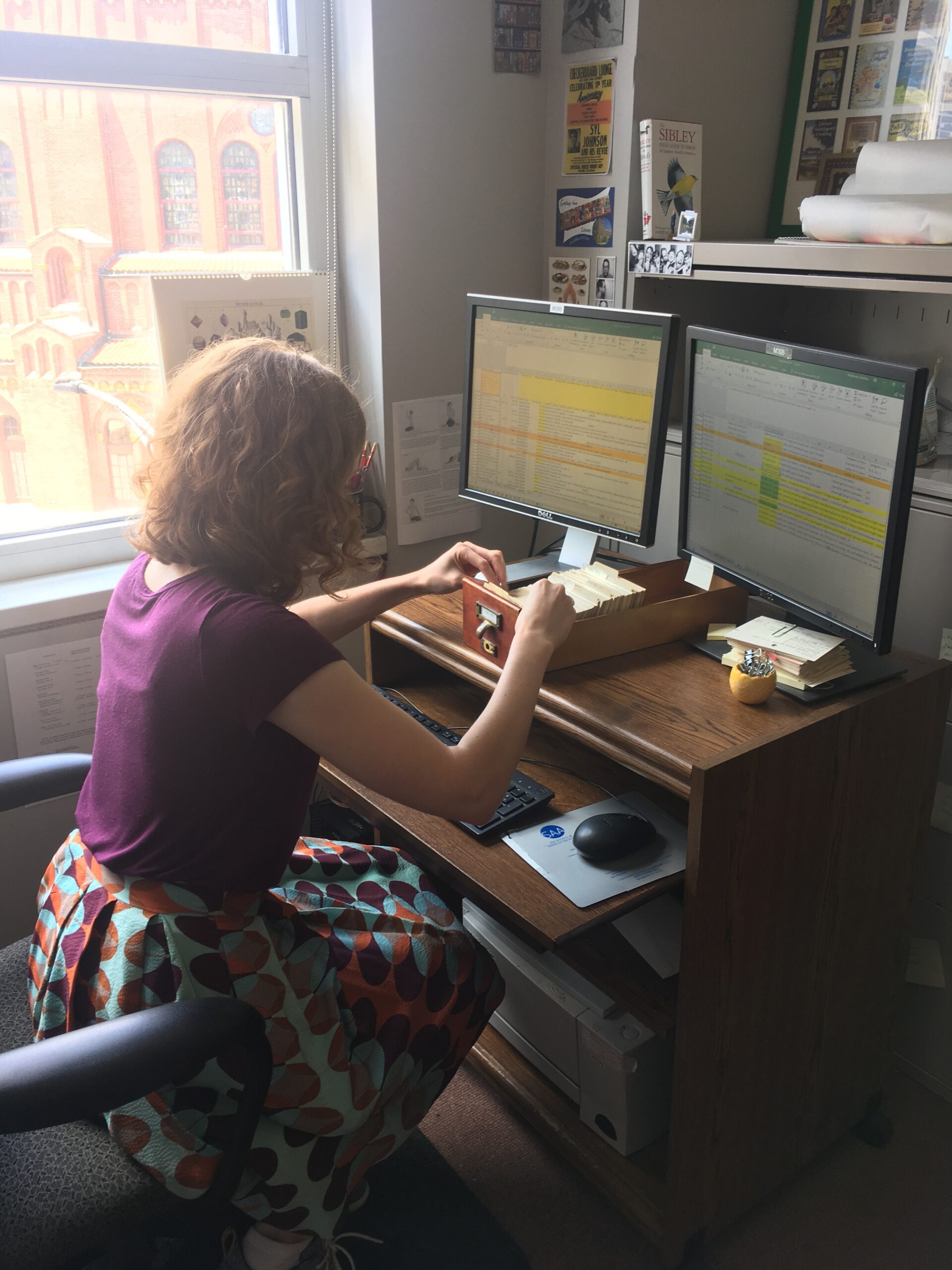

Prior to my arrival, other staff members and many diligent interns had organized the physical catalog card drawers by collection and whether a collection was already in ARCHIE, then entered the information on all of the cards into an Excel spreadsheet. As part of my initial assessment, I looked at the data for every collection and edited it for clarity and ease of use. Sometimes this meant rearranging wording or spelling out abbreviations in compliance with archival standards. It also meant choosing new subject headings to better describe the item. In some cases, when a collection was lacking a catalog card, it meant cataloging the collection from scratch. By the end of April 2019, I had cleaned up the data for more than six thousand collections and performed original cataloging for more than seven hundred collections.

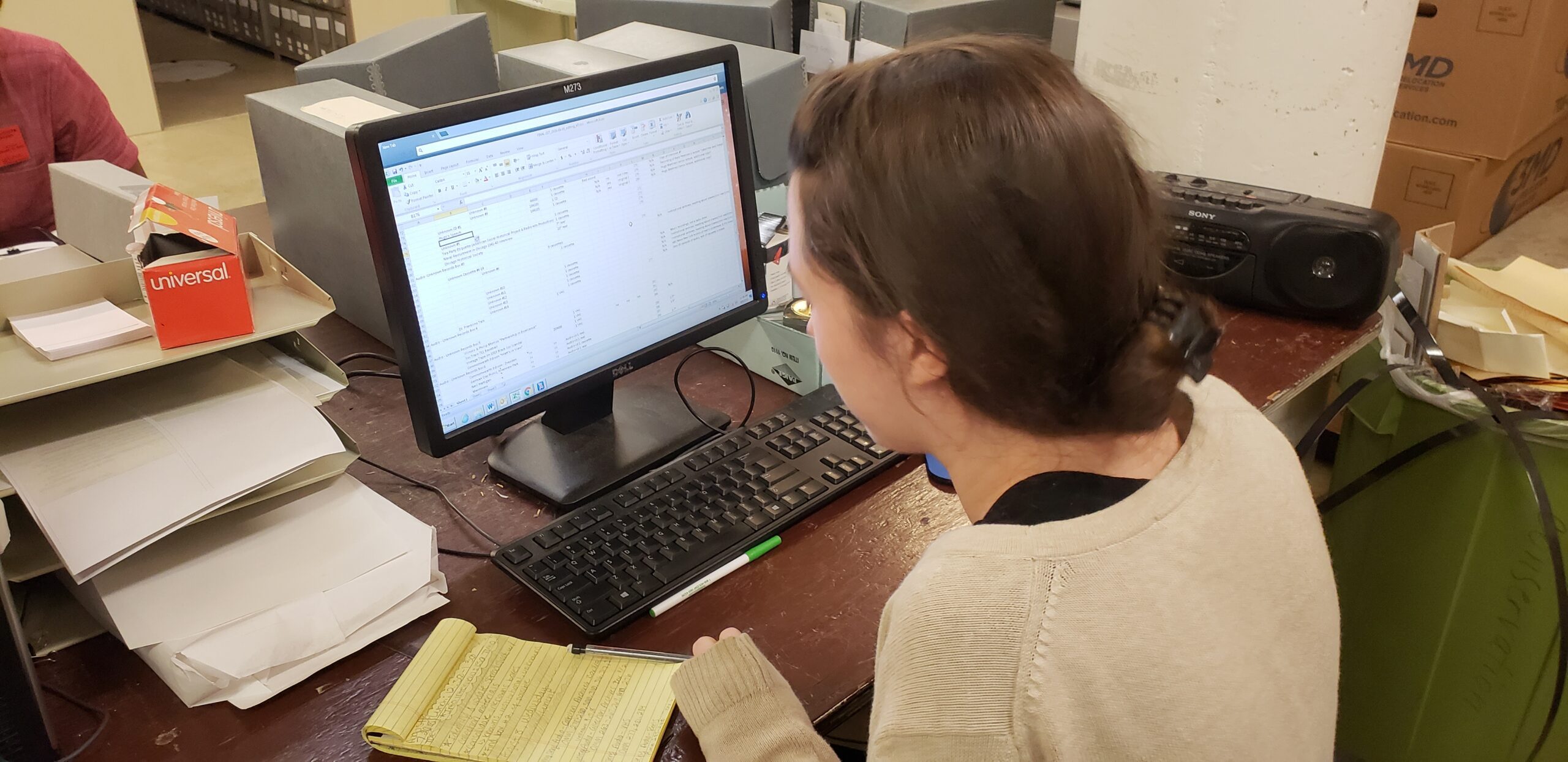

Florio working on transferring data from catalog card to spreadsheet.

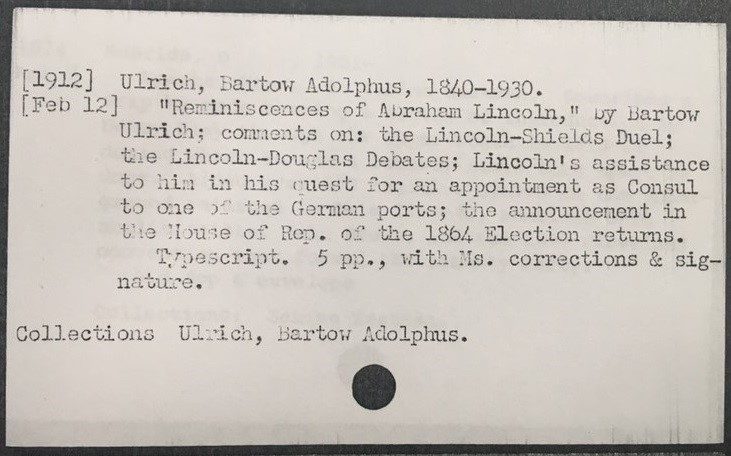

The catalog card for “Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln,” by Bartow Adolphus Ulrich.

Each column in our spreadsheet corresponds to a different section on the catalog card. In the traditional physical card catalog, there are only so many ways the cards can be organized—only so many different entry points and ways to search for a collection—typically the collection title, author, and maybe the most prominent subjects. In an online catalog, however, with all elements and every word of the catalog record searchable, collections can be discovered in new ways.

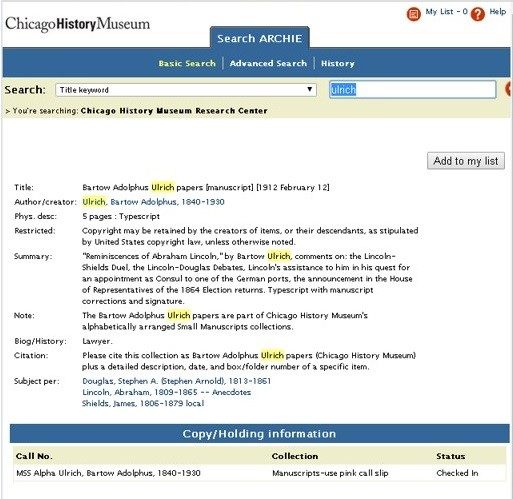

The entry for Ulrich’s work in the CHM online catalog.

Even though these collections belong to the Chicago History Museum, the majority are actually not Chicago-related—they were acquired when the Museum’s collecting scope included American history rather than being exclusively Chicago history. This is mainly due to the Charles F. Gunther Collection that the Chicago Historical Society purchased in 1920. Gunther, a German-born confectioner who lived and worked in Chicago at the end of the nineteenth century, collected anything and everything historical—including the first patent issued by the United States (which was signed by George Washington); the table from Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on which General Robert E. Lee signed the terms of surrender for the Civil War; and even skin from the serpent in the Garden of Eden (which, of course, turned out to be fake).

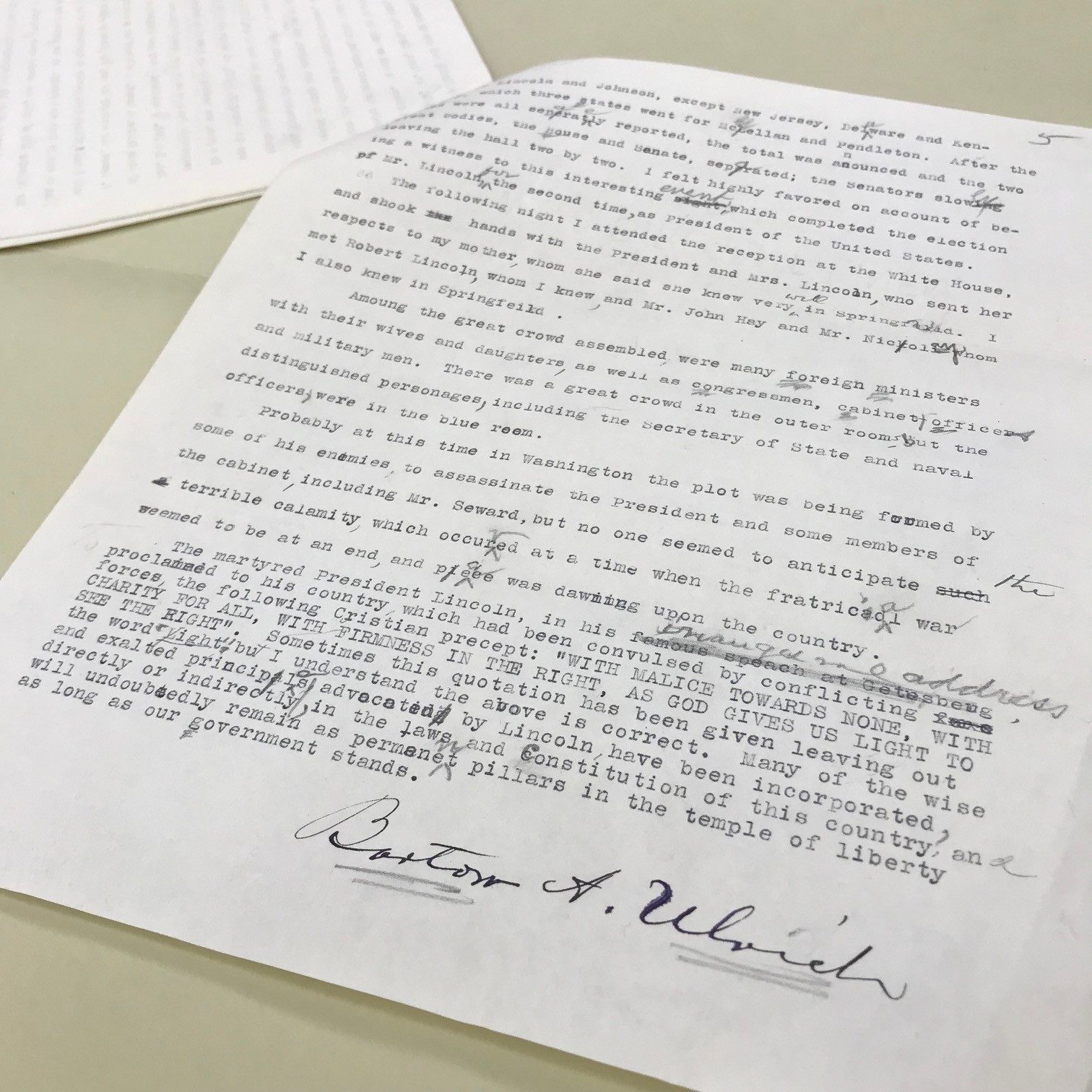

Ulrich’s signed reminiscences with handwritten edits. CHM Small Manuscripts collection

Within the manuscript collections, Gunther items span American history from the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries, which means that the small manuscript topics vary wildly from Colonial America to the Whiskey Rebellion to slavery and the Civil War to Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, Progressive Era, Spanish–American War, and World War I. The Chicago History Museum is thrilled to make all these and more discoverable to an international audience and accessible through the Abakanowicz Research Center.

This Saturday marks one hundred years since the Chicago Race Riot that began on July 27 and ended on August 3, 1919. In this photo essay, CHM assistant curator Julius L. Jones recounts the events of that tumultuous week, as well as the legacy of activism that came from it. All images are from the collection of the Chicago History Museum. Warning: The fifth image is graphic in nature. Viewer discretion advised.

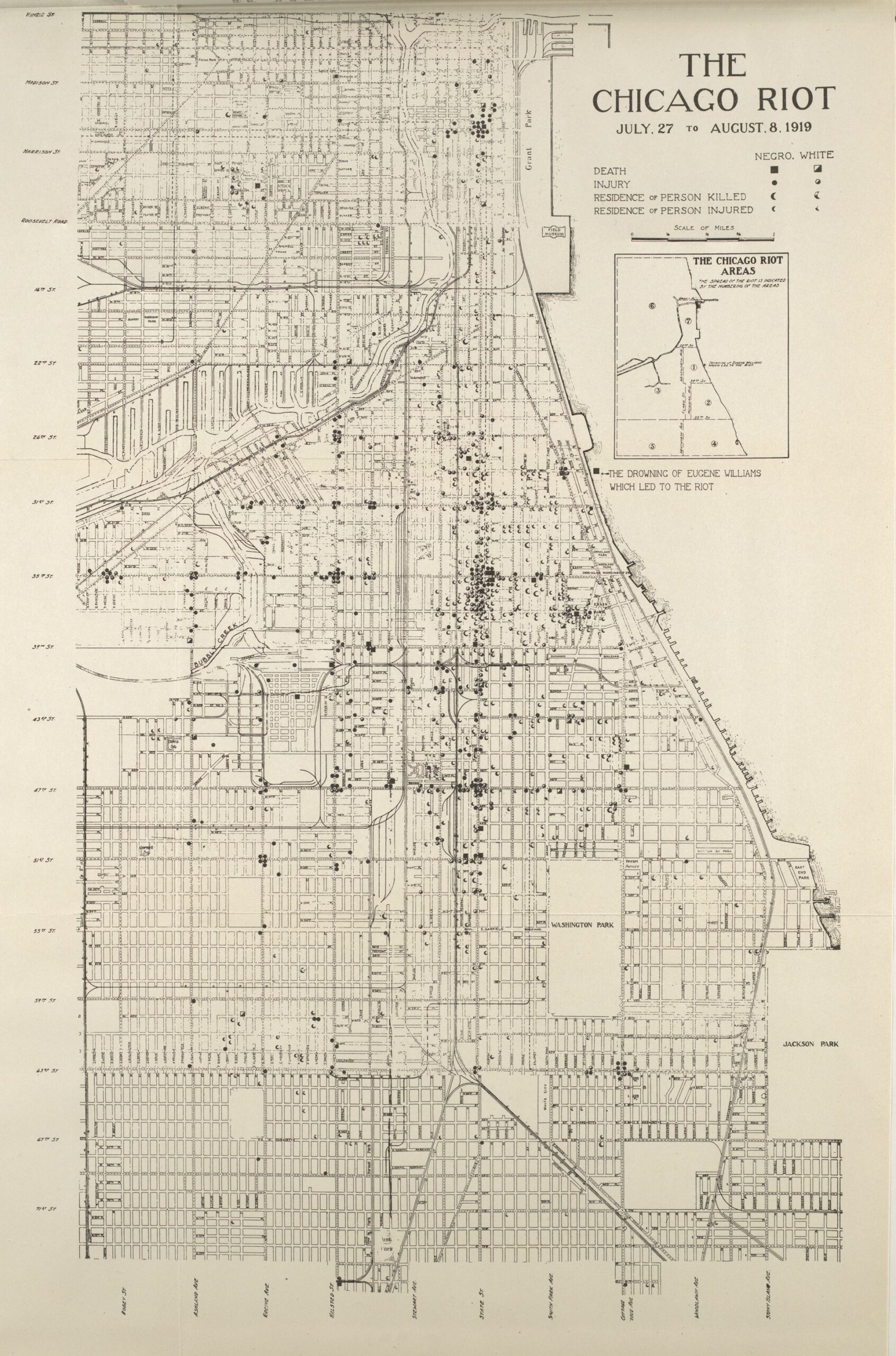

On Sunday, July 27, 1919, thousands of Chicagoans sought relief from the brutal heat on the shores of Lake Michigan. Among them was Eugene Williams, a seventeen-year-old African American. When he and his friends inadvertently drifted across an invisible line that divided the waters by race, a group of whites, insulted by such an act, began throwing stones at them, one of which struck Williams, causing him to drown. In the racial powder keg that was Chicago, his murder was the spark that ignited it during what became the Red Summer of 1919.

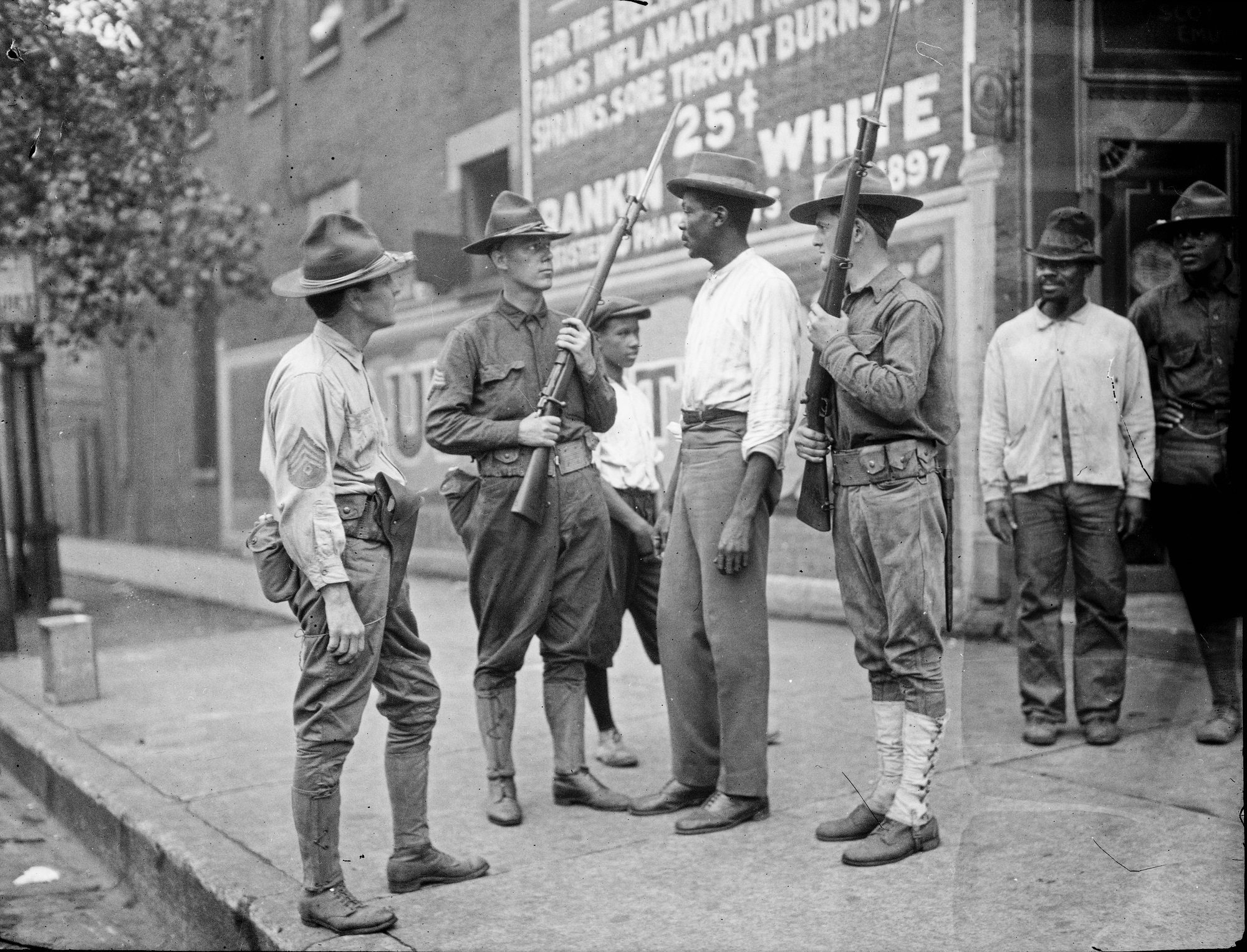

After the drowning of Eugene Williams, the police refused to arrest the white man who was considered responsible for his death. As the crowd grew, the tension escalated, and the fighting began. CHM, ICHi-030315; photograph by Jun Fujita

The violence that started at the beach spread through Chicago’s Black Belt on the South Side, especially in residential areas surrounding the Union Stock Yard. CHM, ICHi-040053

The front page of the Chicago Defender on August 2, 1919, announced the turmoil in the city and listed the names of those who were slain and injured. CHM, ICHi-040222

The police force, owing both to understaffing and the open sympathy of many officers with the white rioters, was ineffective. Only the long-delayed intervention of the Illinois National Guard brought the violence to a halt. CHM, ICHi-065478; photograph by Jun Fujita

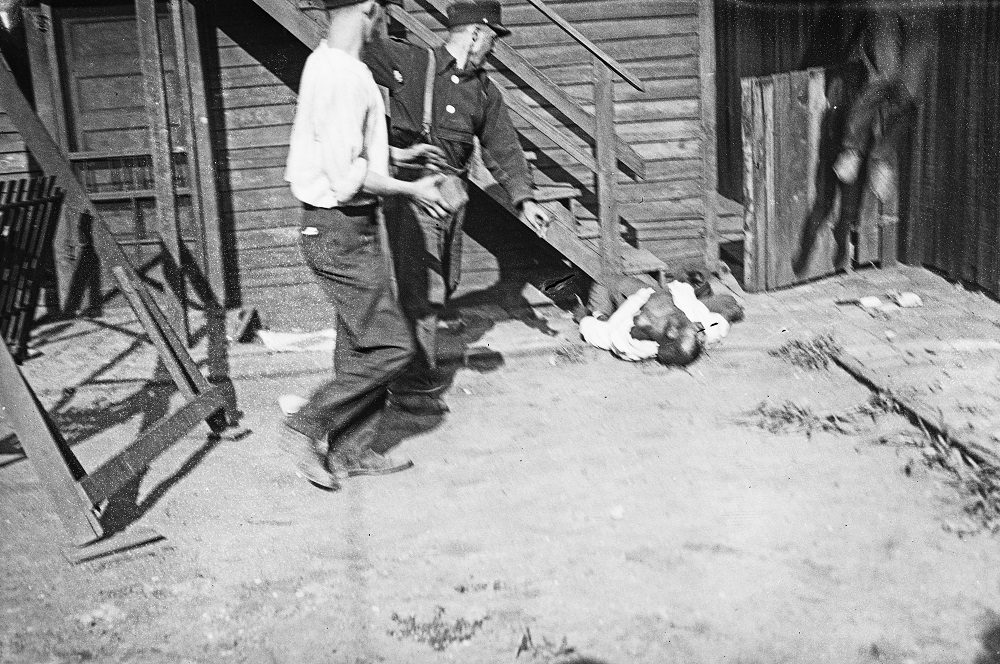

Two white men stone an African American man during the riot. White gangs intentionally went into black neighborhoods to wreak havoc. CHM, ICHi-022430; photograph by Jun Fujita

Rioters ranged from children to adults. Here, a group stands in and around a home that was vandalized and looted. CHM, ICHi-065487; photograph by Jun Fujita

The Riot’s Legacy

After seven days of shootings, arson, and beatings, the Race Riot resulted in the deaths of 15 whites and 23 blacks with an additional 537 injured (195 white, 342 black). Since then, a century of African American activism has challenged the racism and social hypocrisy that allowed those responsible for Eugene Williams’s death to elude justice. Activists continue the fight against racial discrimination in Chicago and the United States.

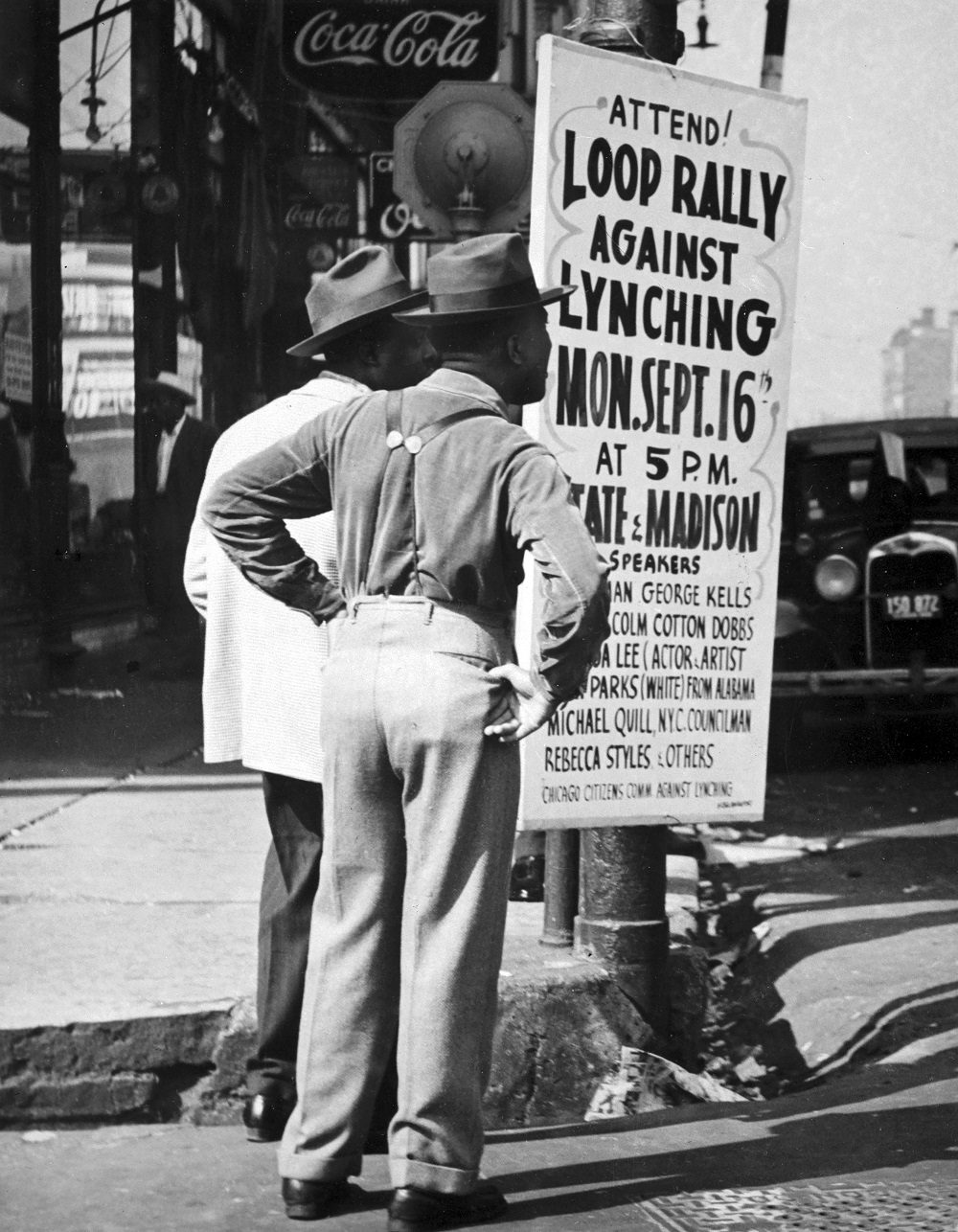

The aftermath of World War II saw a revival of white attacks on African Americans. Here, two men at 31st Street and Cottage Grove Avenue stand next to a sign for a rally against lynching, August 1946. CHM, ICHi-003616; photograph by John F. Weld

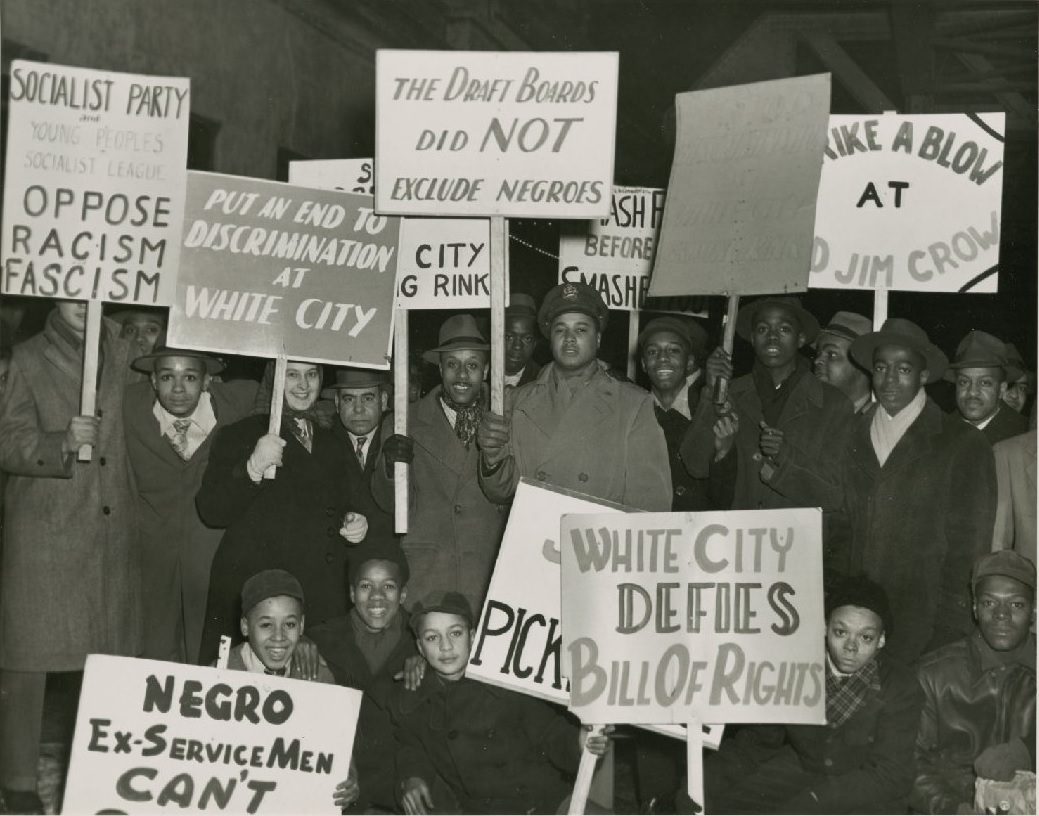

Protests throughout the 1940s and 1950s sought to break down racial barriers in housing, public accommodations, and recreational activities. This one took place at the White City Roller Rink, 63rd Street and South Parkway (renamed Martin Luther King Drive in 1968), Chicago, 1946. CHM, ICHi-019601; photograph by John F. Weld

In the 1960s, the Chicago community of Ashburn saw significant racial strife over school desegregation. This open housing march took place near Bogan High School, August 12, 1966. CHM, ICHi-077756; photograph by Declan Haun

The Chicago History Museum is a partner institution for Chicago 1919: Confronting the Race Riots, a year-long initiative to heighten the 1919 Chicago race riots in the city’s collective memory, engaging Chicagoans in public conversations about the legacy of the most violent week in Chicago history.

CHM Collections Department volunteer Robert Blythe writes about Chicagoan Paul King Jr., a building contractor and social justice advocate, fifty years after the Coalition of United Community Action led a demonstration on July 22, 1969, demanding that building trade unions provide on-the-job trainee positions for minority groups.

Many Chicagoans were taken aback in July 1969 when two hundred demonstrators—including Black ministers, community organizers, and members of the Almighty Black P. Stone Nation street gang—shut down a construction site in the Loop. The issues? The long-standing underrepresentation of African Americans in the construction trades and the hurdles faced by minority building contractors.

The Chicago Defender covered the demonstration. July 23, 1969.

A major player in this fight for greater opportunity was Paul King. King went on to found UBM, Inc., one the nation’s most successful African American–owned general contracting firms. He leveraged this success to become a vocal national advocate of affirmative action and a promoter of expanded training, greater access to credit, and a decent chance for success for minority-owned firms. The Paul King papers at the Chicago History Museum document the activities of this social justice advocate.

Born in 1938 in Chicago, King attended De La Salle Institute, earned a BA from the University of Chicago, and took graduate courses at the University of Illinois at Chicago and Roosevelt University. His work as a house painter while putting himself through school led to his career in the construction business. King tirelessly championed measures to ensure that a portion of the contracts for public construction projects are awarded to minority-owned firms. As his career blossomed, King became an officer of the National Association of Minority Contractors. He developed a close relationship with Maryland congressman Parren Mitchell, working to ensure that minority-owned businesses got a fair shot at federal construction contracts.

The program from the 1975 NAMC annual convention, which King attended. CHM, ICH-i085667

King comments on Fullilove v. Klutznick, which affirmed lower court rulings that allowed federal funds to be earmarked for minority groups. CHM, ICHi-085667

Paul King always believed that social justice activism was entirely compatible with business success. He has written extensively and lectured widely on ways to overcome the legacy of discrimination and neglect endured by African Americans. King has organized college courses for minority business owners and hired ex-convicts in his business. His papers at CHM cover all aspects of his career as businessman, writer, and social reformer.

King (left) with Chicago mayor Eugene Sawyer, c. 1987. CHM, ICHi-085685

Additional Resources

- Visit the Abakanowicz Research Center to see the Paul King papers.

Project archivist Rebekah McFarland writes about her experience processing the Thing magazine records, which will be available for public access at the CHM Research Center in May.

When Robert Ford, Trent Adkins, and Lawrence Warren founded Thing in 1989, they did so to fill a void in the publishing world. In a 1994 interview with Owen Keehnen, Ford stated, “We knew for ourselves what a rich and important cultural thing gay black men have and share. We wanted to make a magazine that would be a way of documenting our existence and contribution to society.” Much like Think Ink—the two-issue ’zine the three published with the assistance of Simone Bouyer from 1986 to 1987—Thing was published in Ford’s living room with a small, mostly volunteer staff. The quality of both Think Ink and Thing, however, is notable; the layout and format are highly professional, the articles well researched, the photographs and artwork detailed in their attributions. This care and attention spanned all ten issues of the ‘zine, which ran into 1993.

A subscription card for Thing magazine. All images by CHM staff

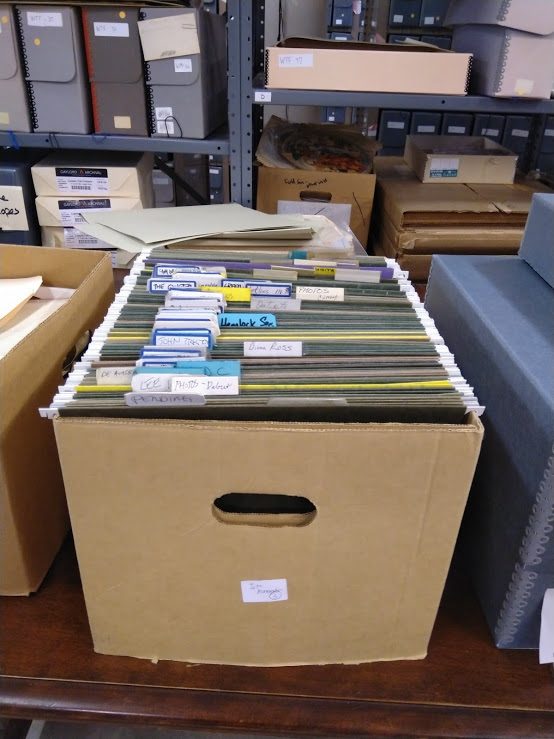

When I began, the collection was housed across eighteen boxes and one poster tube. An initial survey gave me an early feeling for the collection and allowed me to do three things: estimating the supplies needed to rehouse the collection; determining how intact the original order was; and determining the different series and subseries for the collection.

The first was simple: many documents were still housed in hanging folders, negatives and photos needed envelopes, and larger items needed proper housing. My second take away led directly into the third: roughly twenty years ago the collection had been partially processed by an archivist with different processing standards in mind. As a result, original order had been interfered with, so I felt it even more important to maintain what order remained.

The collection itself consists of everything that went into making Thing what it was. Issue drafts, submissions, photographs, artwork, correspondence, and distribution material make up a large part of the collection. In addition to this, Ford was very much a cultural documentarian, collecting articles and pictures regarding all aspects of black and LGBTQIA life in Chicago. As such, one of the biggest challenges in processing the collection was one of the things that makes Thing so important: the collection is highly intersectional.

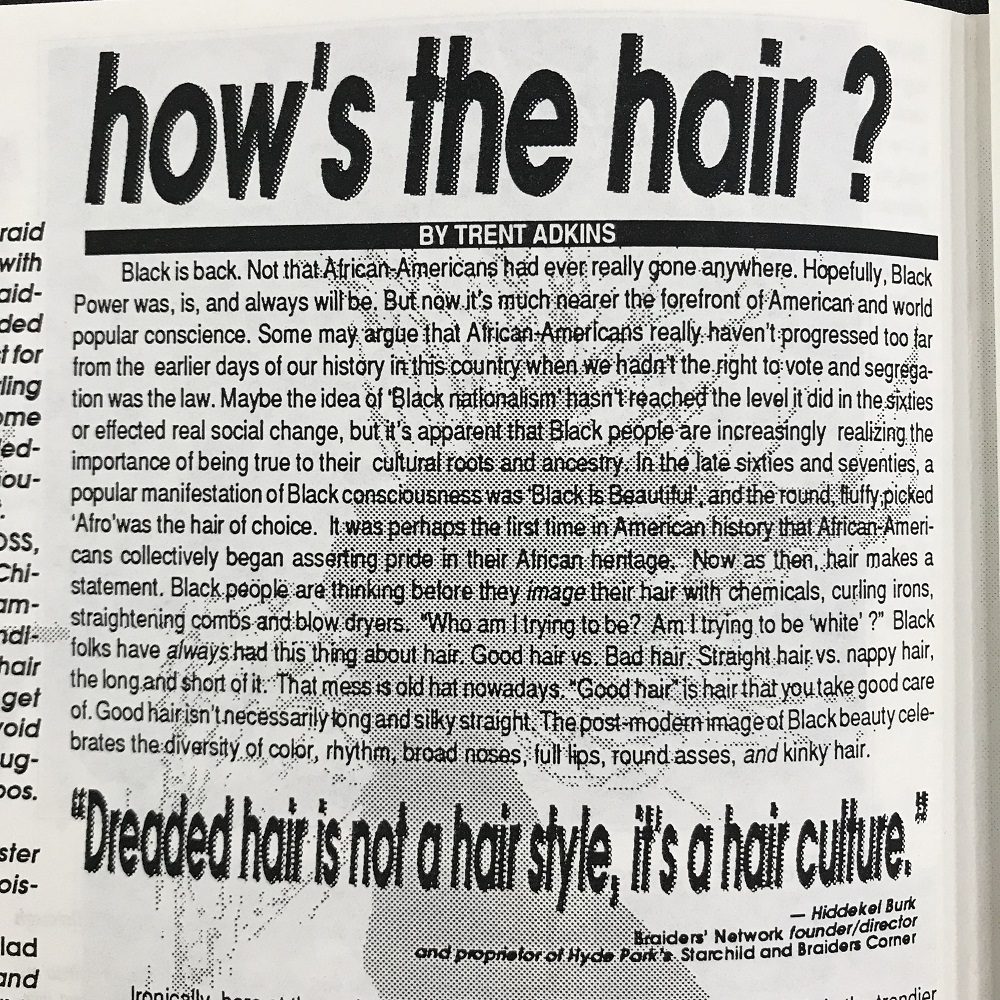

A column written by Trent Adkins, one of the cofounders.

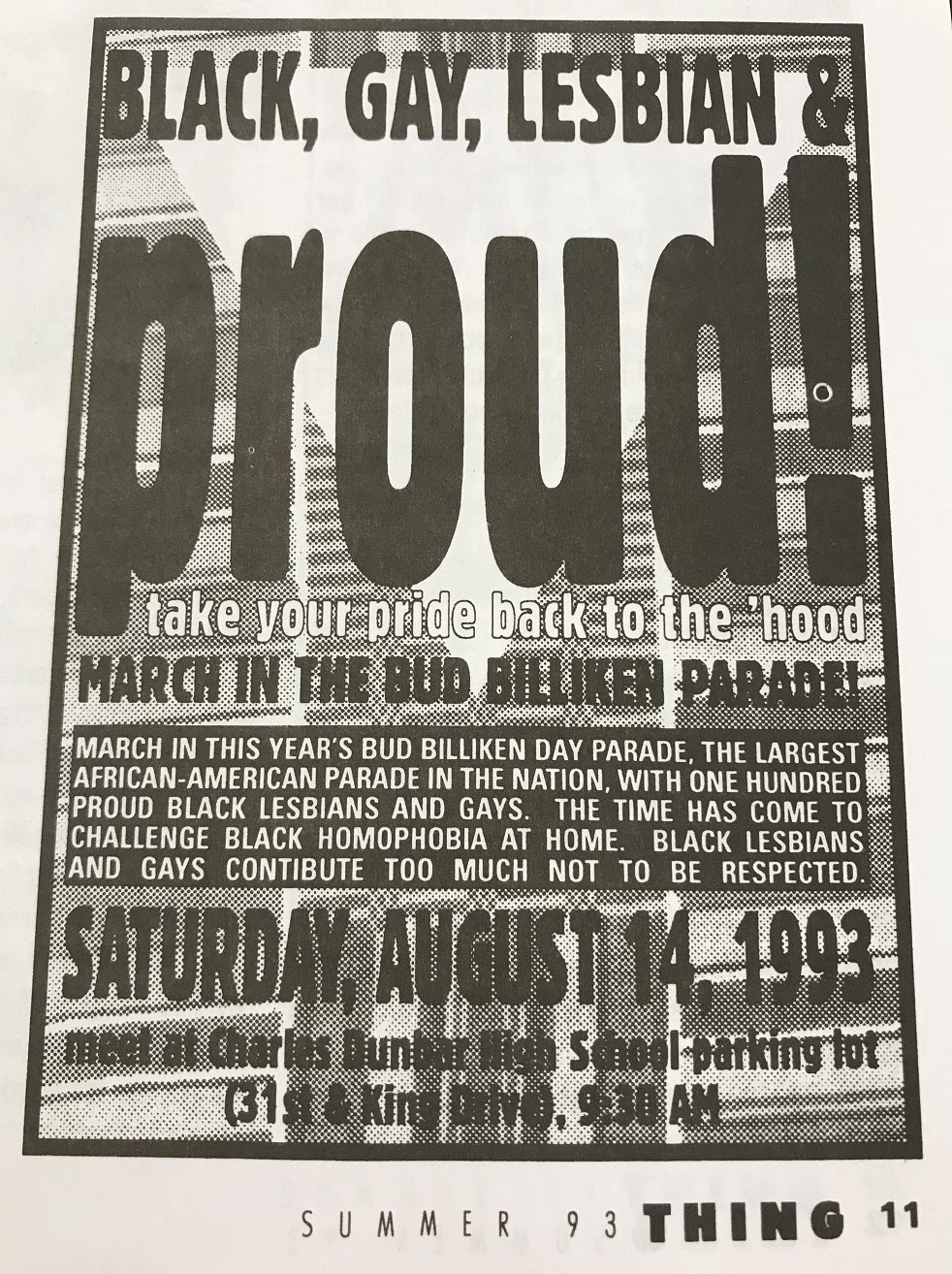

An advertisement calling for participants in the 1993 Bud Billiken Parade.

As I processed the collection, I had to figure out how to approach its intersectional nature. Many collections are easy to sort into distinct series: minutes, letters, programs, etc. Thing, however, highlights the reality that life is not easily compartmentalized. As it was, many of the items fell within the context of multiple subseries. To best preserve the remaining original order, I decided not to interfere with this. Instead I inserted a note in the finding aid regarding this characteristic.

The processed collection.

I am grateful to have been given the room to push against standardized procedure and have been able to grow as an archivist due to this project. It’s my hope that as institutions begin to acquire more representative collections, we archivists are continuously pushed to adapt our methods and evolve our approaches.

Processing and digitization of the Thing magazine records supported by The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation.

Enrich your instruction with Great Chicago Stories, an award-winning suite of twelve historical fiction narratives and supporting classroom resources. Download the narratives, which were written and classroom-tested by local teachers, and corresponding artifact sets. Use the map interactive to see where the historical events happened and how those same places look in contemporary Chicago.

Visit http://chicagohistoryresources.org/greatchicagostories/ for more information.

Please note: The “Trading Mystery” story and associated materials are currently under review. As we work toward sharing complex and inclusive histories, it is imperative that at times we step back and review resources and materials to ensure that they are culturally responsive, historically accurate, and actively antiracist. Please check back for updates as our review process continues.

Streamlined design found a welcome home in American kitchens. In the mid-1930s, as the economy began to improve, consumers looked to update their homes. Then as now, most people began with their kitchens, and Chicago supplied the market with a multitude of streamlined products.

At the top of the list stood a group of Sunbeam appliances made by the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company. Established in 1897, the company originally made sheep-shearing and horse-trimming equipment before adding a line of small household appliances in 1921. Well-designed and made to last, Sunbeam appliances gained a national reputation for quality that helped the company survive the Great Depression. After World War II, Flexible Shaft changed its name to the Sunbeam Corporation. They stayed in Chicago until the early 1980s before moving to their current location in Boca Raton, Florida.

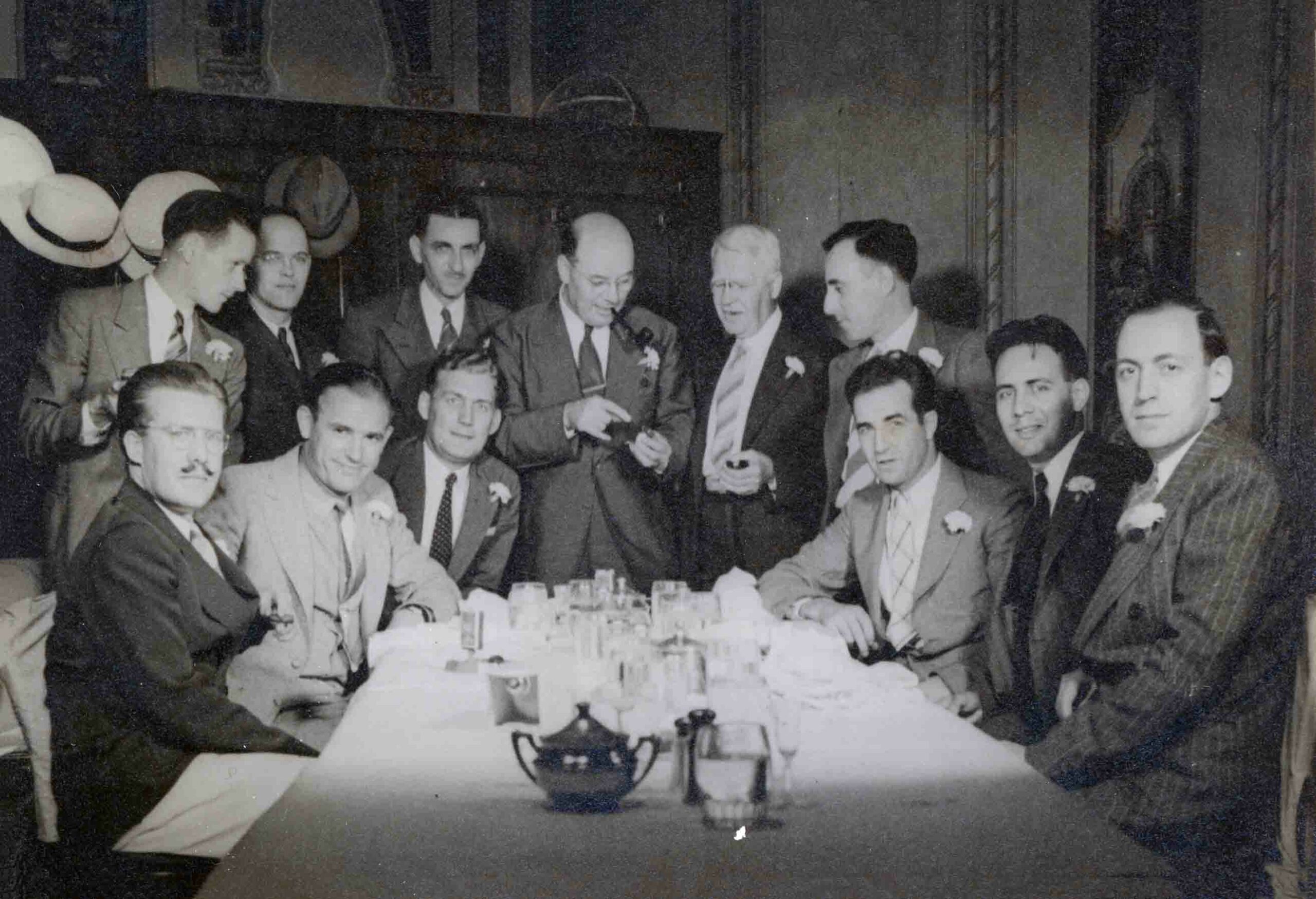

The Sunbeam Team, c. 1940

Courtesy of Tasha Coats

This image includes George T. Scharfenberg, seated on the far left. Standing immediately behind him is engineer Ludvik Joseph Koci, while chief engineer Ivar Jepson is seated on the far right.

A talented team of designers and engineers created Sunbeam appliances. They were led by Ivar Jepson, a Swedish-born electrical engineer who in 1929 started working for the Chicago Flexible Shaft Company. Jepson developed the original Sunbeam Mixmaster. In 1936, the company hired George T. Scharfenberg to update their product lines with a more streamlined look. Scharfenberg collaborated with Jepson and other company engineers on many products that became icons of American design.

Sunbeam Model 5 Mixmaster, 1938–39

Designed by Ivar Jepson and George T. Scharfenberg, Chicago, Illinois, 1938–39

Painted metal body with Bakelite controls and handle, glass bowls, and stainless-steel beaters

Courtesy of William E. Meehan, Jr.

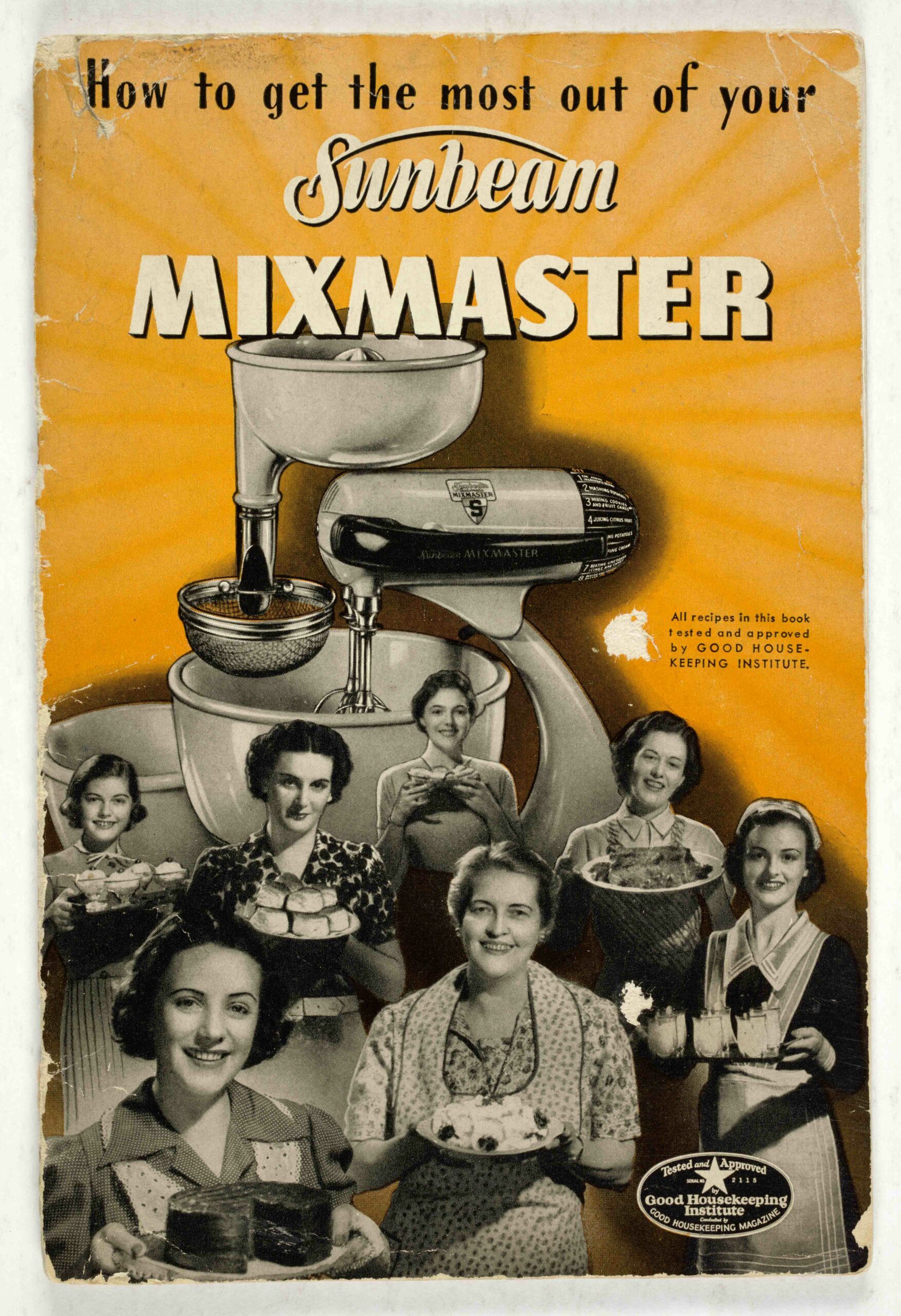

How to get the most out of your Sunbeam Mixmaster, 1940

Owner’s manual with recipe page published by Chicago Flexible Shaft Company

Chicago History Museum, ICHi-173668

A streamlined body and powerful motor made the Model 5 Mixmaster a national best seller. The manual advised owners to “Keep Your Mixmaster Out” and “plugged in ready for instant use at the turn of the switch.” Owning a Mixmaster became something of a status symbol for most Depression-era Americans who had to scrimp and save for every purchase.

Sunbeam Coffeemaster Model C-20, 1938

Designed by Alfonso Iannelli for the Chicago Flexible Shaft Co., Chicago, Illinois, 1938

Chromium-plated copper vessels with Bakelite top, base, and handles

Chicago History Museum, Gift of William E. Meehan, Jr., 2018.13.1–4

The Sunbeam Coffeemaster exemplifies Chicago’s ability to mass-produce and mass-market streamlined goods. Its spherical body housed a patented internal thermostat that allowed one “to simply put water in the lower vessel and coffee in the upper vessel—and forget it.” Despite a steep price of $16 ($280 today), the Coffeemaster quickly became a national best seller and remained in production until the late 1950s.

Sunbeam Ironmaster Model A-4, 1939

Designed by George Scharfenberger, Chicago, Illinois, 1939

Chrome with Bakelite handle

Chicago History Museum, Gift of Michael Trenary, 1988.414

The Sunbeam Ironmaster featured a streamlined body and thumb-tip heat regulator in the handle. As advertised, its “perfectly balanced” body would put an end to “tired arms and shoulders.”

Sunbeam Shavemaster display unit, 1939

Designed by George Scharfenberger, Chicago, Illinois, 1939

Chrome, metal, glass, and Bakelite

Chicago History Museum purchase, Anna Hasburg Fund, 2017.11.1ab

Effective advertising played a big role in Sunbeam’s success. The display unit, used at sales counters, lit up and featured an operating shaver with a mirror to check results.

These Sunbeam appliances and other streamlined products from the 1930s–50s were on display in the exhibition Modern by Design: Chicago Streamlines America.

In a world of podcasts and online streaming, CHM collections intern Angela Thomas demonstrates that audio cassette tapes are still in use. In this blog post, she summarizes her work identifying and labeling audio content as part of her internship through the DePaul University museum studies certificate program.

Just as people do not always remember to label their photographs, they also do not always label their audio cassette tapes. During the summer of 2018, I had the unique opportunity to help investigate the mystery of unidentified audio cassette tapes at the Chicago History Museum. Since cassette tapes are a bit before my time, I was unaware that they were still vastly abundant in archives, but after hunting down a cassette player and listening to fifty-three mystery cassettes, I now know that they are not only abundant but invaluable for the information that they contain.

Cassettes, such as these, contain many important archival materials, including oral history interviews and recordings of lectures held at the Museum.

Many of the mystery cassettes were completely unlabeled and, thus, their contents were truly unknown. The rest of the tapes had labels, but often, the text was not helpful in identifying what was recorded. Nevertheless, label or no label, nothing about the cassettes revealed their contents or where they belonged until someone listened to them. Many tapes required significant attention: Some had to be listened to for thirty minutes before the contents and subject were clear. Others needed only ten minutes for the same amount of clarity. Deciphering the contents of each tape was the biggest challenge. Some were obviously oral histories, but an oral history about who or what? Other cassettes revealed themselves to be radio program recordings, but I still had to figure out what station recorded it, who the speaker was, and what they were talking about.

I used this duel compact disc/audio cassette player to listen to the cassette tapes. As you can see, the CD player no longer works.

Once I had enough information from a cassette, I needed to determine to which collection it belonged. Referencing the online catalogue, ARCHIE, and using internet searches, I was able to use the keywords I had gathered, including names, places, organizations, or movements, to find out if a tape had a connection to a particular collection. I then updated the inventory with my findings. Many of the mystery tapes did not belong to the collection and were actually institutional archives—recordings of guest lectures, meetings, and special events, such as the Museum’s bicentennial celebration of the Constitution.

CHM collections intern Angela Thomas types her content notes after listening to cassette tapes.

I thoroughly enjoyed playing audio detective. Listening to the tapes was a treat because I was able to experience all the cassettes as if I was attending a particular guest lecture, radio program, or interview. Being able to connect the items to their collections and properly identify them in the finding aids, as well as discovering institutional archival materials, was a rewarding experience, because I know that these materials are now easier for staff and researchers to find and use. Interning at the Museum was an unforgettable experience, and I learned more than I could have imagined about the Archives & Manuscripts department, the Museum, and its collections. I am most happy that uncovering the secrets of the mystery audio has added more voices to the collection and that the work I did helped make that possible.

Last summer, CHM collections intern Cara Caputo worked with collections manager Britta Keller Arendt to continue the ongoing inventory of the Decorative and Industrial Arts collection. This led her to discover just how much investigation working with the collection entails. CHM publications interns Lily Stachowiak and Brendan Narko helped organize and publish this blog post.

The primary goal of an inventory is to keep track of the artifacts in a museum collection. The process entails photographing each object and recording its location, dimensions, and physical description. During my summer internship, I had the opportunity to contribute to CHM’s ongoing inventory of its Decorative and Industrial Arts (DIA) collection. While I predicted that this project would allow me to discover several fascinating objects, I underestimated just how much detective work I would be performing.

My fellow intern and I soon learned that some objects in DIA storage are better documented than others. In most cases, an accession number is clearly written on or near the object, allowing us to connect the physical object with its record in The Museum System (TMS), which is the collections database, or CHM’s written records. Whenever an object is found without an accession number, however, this important link is missing. This is where the detective work begins as we attempt to determine the who, what, where, and when of an object.

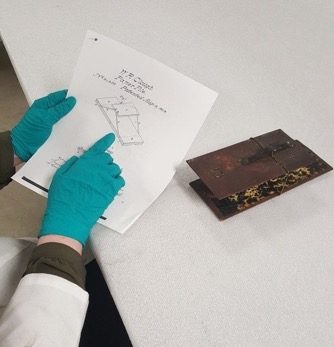

The function of this flat, rectangular device was not immediately apparent to the collections interns. All photographs by Lily Stachowiak

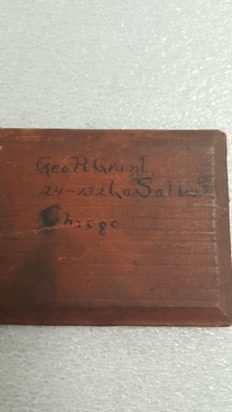

One particular mystery that we were determined to solve began when we found a flat, rectangular object that we first assumed to be a vintage mousetrap, as the object’s mechanisms and design matched our idea of modern mousetraps. Without an accession number, we searched for other markings and discovered a name and address on the back. This was the first clue that we would use in our investigation.

The back of the device was marked with the name and address of its owner, George R. Grant.

We assumed that this man was the donor, but when we searched the Museum’s records, we discovered no record of a George R. Grant donating anything resembling our mystery object. Upon further research, we learned that Mr. Grant was a prominent attorney in Chicago in the late 19th century. While this information did not immediately reveal the identity of the object, it nonetheless uncovered an important aspect of the object’s history.

The next clues the object gave us were two patent dates, one from 1865 and the other from 1868. We began to search the United States Patent and Trademark database and compared the patents granted on each date in hopes of discovering patents that were issued to the same individual. After we failed to discover a match, we decided to examine the physical object for more clues. When we took a closer look at the text above the patent dates, we made out the words “bill holder.” Returning to the database, we refined our search to patents issued on each date that contained the keywords “bill” or “holder.” Sure enough, we soon discovered two patents that matched both the mechanisms and patent dates found on the object. We finally pieced together the mystery: this object combined two mechanisms in order to create an efficient bill holder that George R. Grant presumably utilized in the late 19th century.

The bill holder utilized two patented mechanisms, allowing its owner to store bills easily and securely.

Of course, we had to verify that our discoveries were correct, which we were able to do when we searched the TMS database and found a match for a “bill holder.” With our research and detective work, we updated this object’s TMS record and provided further information on the donor and the object itself, preventing future Museum staff from confusing this 19th-century bill holder with a mousetrap!

In this blog post, CHM collections intern Chris Johnson writes about his experience processing the collection of The Chicago Reporter under the supervision of senior archivist Julie Wroblewski.

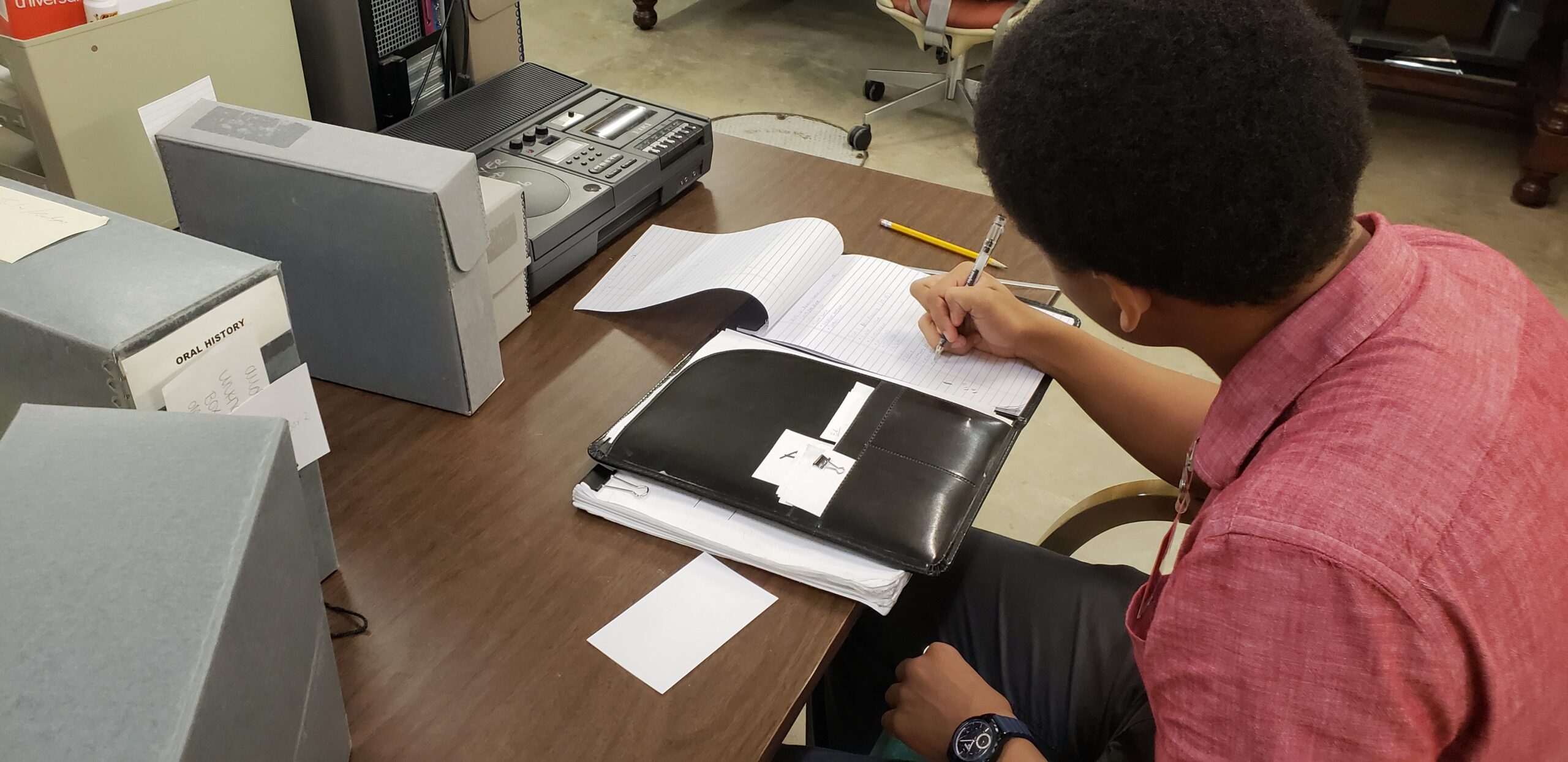

Last summer, I interned at the Chicago History Museum via the Black Metropolis Research Consortium’s Archie Motley Archival Internship Program. The Black Metropolis Research Consortium (BMRC) is a Chicago-based membership association of libraries, universities, and other archival institutions that helps make accessible its members’ holdings of materials that document African American and African diasporic culture, history, and politics, with a specific focus on materials relating to Chicago.

CHM collections intern Chris Johnson writes notes while processing The Chicago Reporter collection.

During my internship, I got hands-on experience with several aspects of museum work, specifically what it’s like to be an archivist. Previously, I had understood museums only from the perspective of a visitor. When given the opportunity to take part in the processing of a collection, I was met with the reality of just how little I knew and was excited to correct this with my summer task of processing the records of The Chicago Reporter.

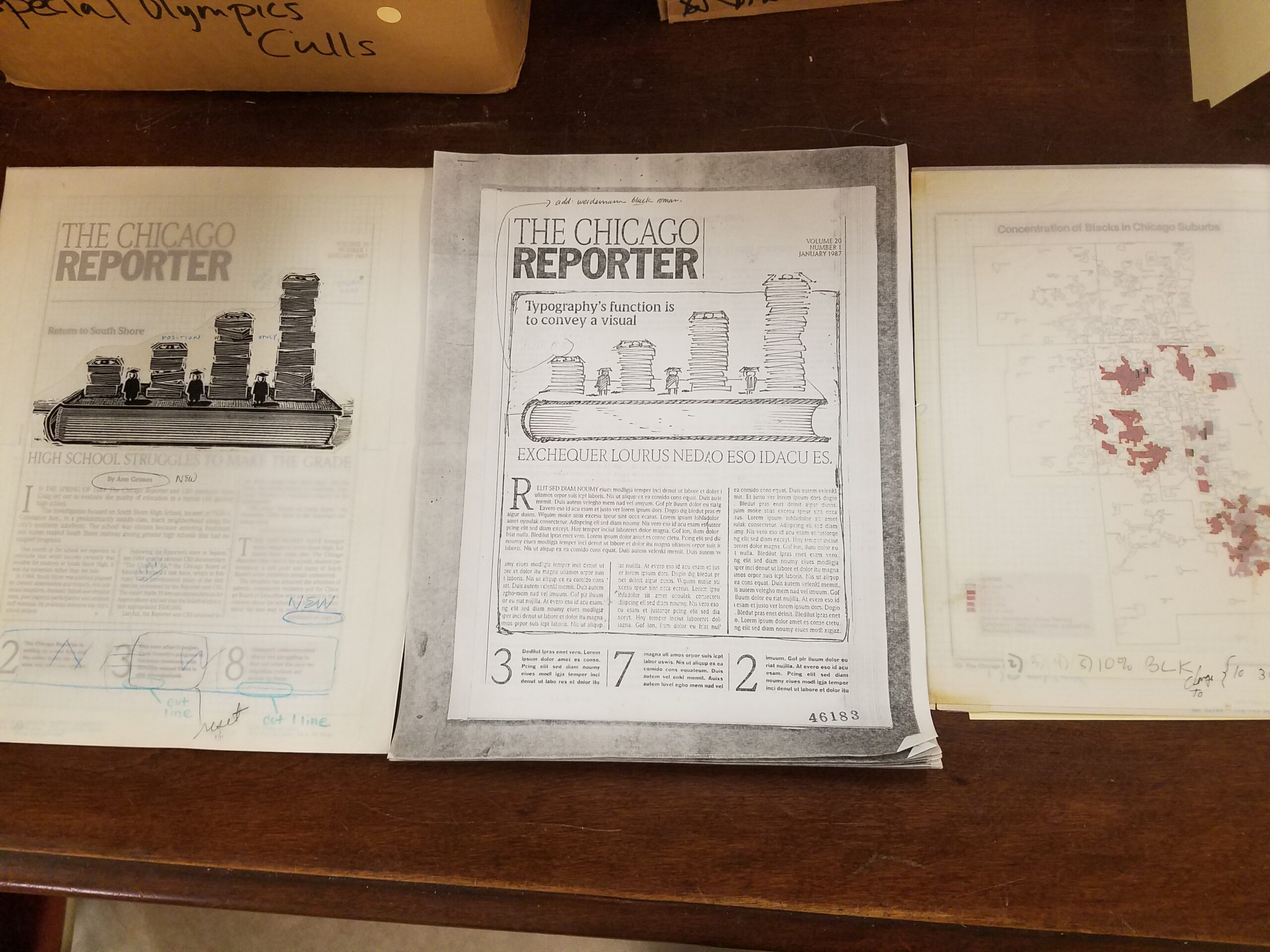

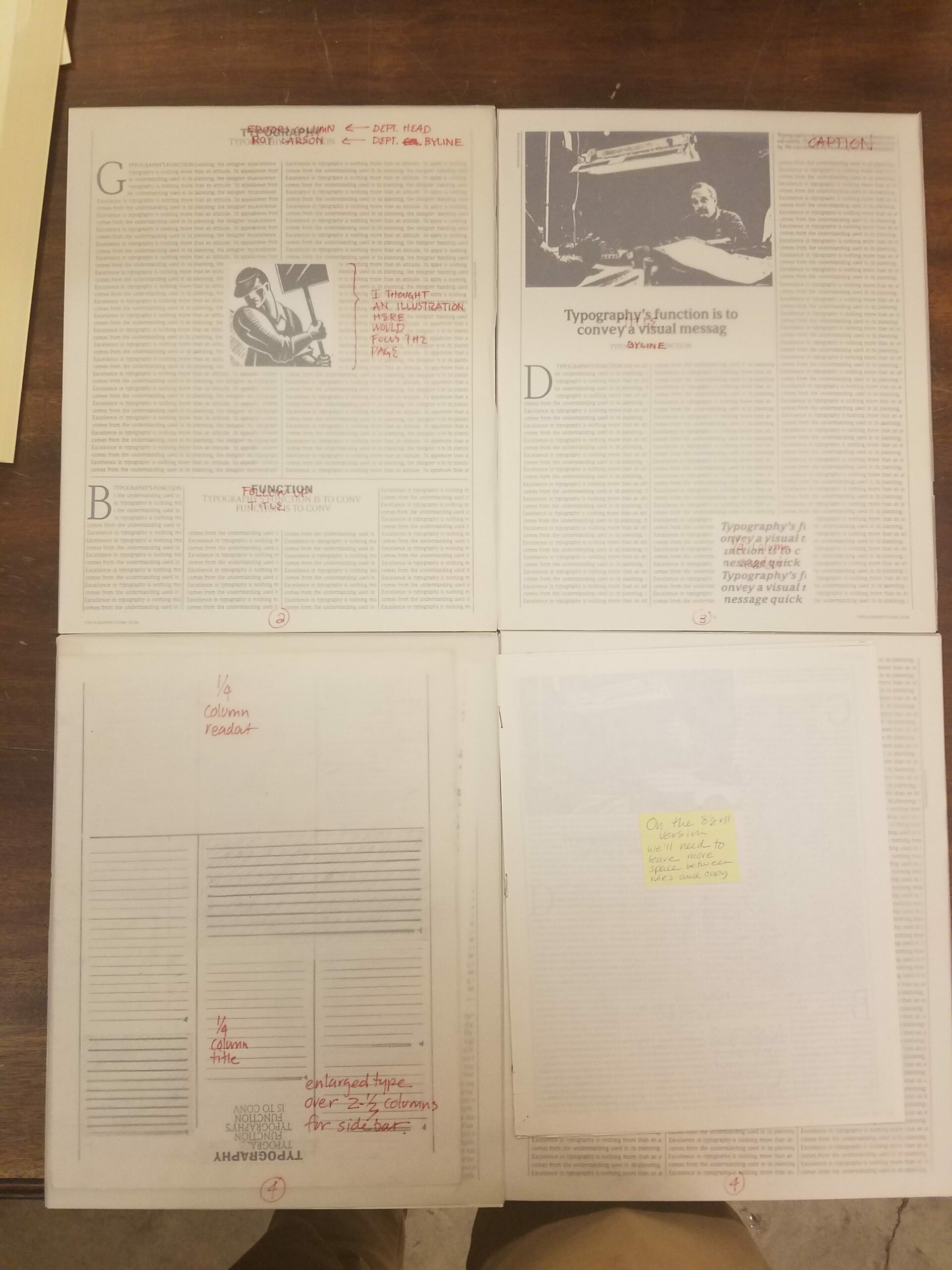

Copies of The Chicago Reporter front pages with edits as well as a map detailing the black population of Chicago’s suburbs. The Chicago Reporter papers, oversize folder 1

The Chicago Reporter is a periodical founded in 1972 by civil rights activist John A. McDermott, whose focus was to report and discuss race and poverty within Chicago. To process the collection, I started by surveying the materials for content and condition and then organizing them into categories, known as series, so a researcher could easily go through the collection with sufficient understanding of what was there and how to navigate it. I learned that it was important to maintain respect for the original order of the materials, ensuring that the way it was organized when it was acquired is preserved as much as possible. Seeing that order gives researchers more context for the materials and potentially some insight into how the organization conducted its work.

While arranging the materials, certain pieces stood out to me, such as a list of subscribers from the mid- to late 1970s and templates for how to design the publication, including large plastic and paper graphics demonstrating how articles were to be orientated on the page with relation to pictures. The annual readership surveys gave a snapshot of their readers’ feelings (and thus part of society’s) at a given moment in time. The handwritten draft revisions and interview notes showed how research developed into a final published article and highlighted how thorough the publication was in its production of the finished product.

Pages of The Chicago Reporter with copyedits. The Chicago Reporter papers, box 29, folder 3

After arranging the collection, I ventured into the final stage of processing the collection: description. To do this, I learned to encode a finding aid, or collection inventory, in XML using a set of standards called Encoded Archival Description (EAD). This turns the finding aid into a document that can easily be put on the web and shared with other online catalogs to increase its discoverability. By working with these thirty-year-old documents, I gained an intimate connection with the collection and an insight into what Chicago was like in the late 1970s to mid-1980s.

The Chicago Reporter papers can be accessed through the Chicago History Museum’s Abakanowicz Research Center.