Latest Posts

Blues Music Comes to Chicago

Eleven-year-old Penny and her family are part of the Great Migration, moving from Mississippi to Chicago. Their first day in the city is full of new sights and sounds and meeting extended family members. Read or listen to A Bronzeville Story, then make a scrapbook page of Penny’s first day in Chicago. Share all of your creations on social media using the hashtag #CHMatHomeFamilies

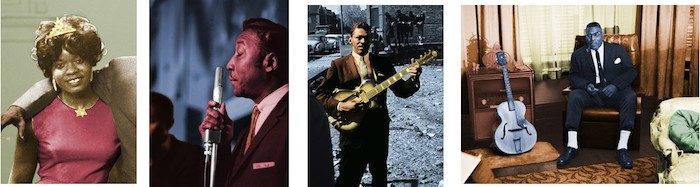

Blues Biographies

Meet some famous Chicago blues artists and match their stage name to their biography. Then use our fun name generator to choose your own stage name and make a backstage pass! Share all of your creations on social media using the hashtag #CHMatHomeFamilies

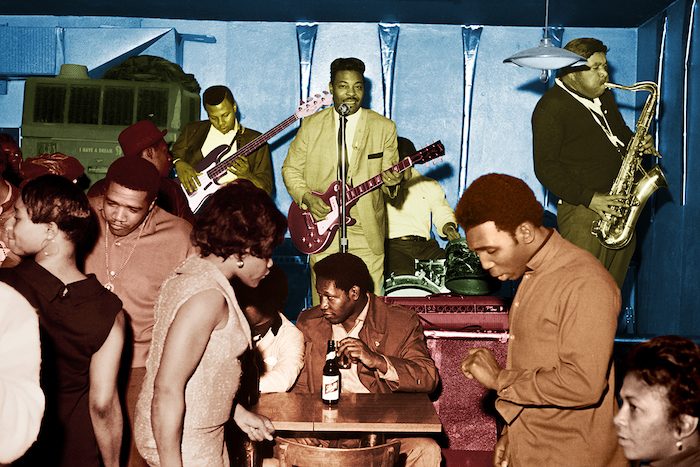

Picture This!

The photographs of Raeburn Flerlage capture the exciting blues scene in Chicago during the 1960s. Try the 3-2-1 technique to take a closer look at some of his images, then use your imagination to enter your favorite one and make music history! Share all of your creations on social media using the hashtag #CHMatHomeFamilies

Blues Bingo!

Use our images to make your own bingo cards all about blues music. Then have fun playing with your family and see how many times you can call out “Blues Bingo”! Share all of your creations on social media using the hashtag #CHMatHomeFamilies

Sing It!

“Sweet Home Chicago” is a famous blues song about the city. It’s your turn to be a star: use our templates to write your own version of “Sweet Home Chicago” and sing your heart out! Share all of your creations on social media using the hashtag #CHMatHomeFamilies

Hood by Hood: Discovering Chicago’s Neighborhoods

This week’s challenge explores the rich history of Back of the Yards. When European immigrants came to Chicago, they faced many challenges. In response, they made choices that shaped the neighborhood of Back of the Yards, making it an essential part of the city’s identity. Explore images of the area, read a short article about its history, dig deeper via a short video about the neighborhood, listen and read along with a member of CHM’s education team using a short audio, and get creative as you design a star for the Chicago flag representing Back of the Yards.

Barrio por Barrio: Descubriendo los Vecindarios de Chicago

El reto de esta semana explora la historia del vecindario de Back of the Yards. Cuando los inmigrantes europeos y europeas del este llegaron a Chicago, se enfrentaron a muchos desafíos. En torno, tomaron decisiones que dieron forma al vecindario de Back of the Yard, haciéndolo una parte esencial de la identidad de la ciudad. Explora imágenes del vecindario, lee un breve artículo sobre su historia, investiga a través de un video corto sobre el vecindario, escuche y lea junto con un miembro del equipo de educación del museo usando un breve audio, y use su creatividad al diseñar una estrella que represente el vecindario.

View of the intersection of South Ashland Avenue and West 47th Street crowded with men in the streets during the 1904 Stockyards Strike in Chicago, between July 7 and September 9, 1904. DN-0000883, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Back of the Yards is perhaps best known as the former home of Chicago’s meatpacking industry. In the nineteenth century, meatpacking emerged as a major industry and signaled the beginning of industrialization in Chicago. But working conditions varied at packinghouses, and the benefits of modern industry came with a price. In this week’s activities, discover how labor unions helped address these issues and what they are currently doing for workers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

El barrio Back of the Yards es quizás mejor conocido como el hogar de la industria del envasado de carne en Chicago. En el siglo XIX, el envasado de carne surgió como una industria importante y marcó el comienzo de la industrialización en Chicago. Pero las condiciones de trabajo variaban en las empacadoras y los beneficios de la industria moderna tenían consecuencias. Vea cómo los sindicatos ayudaron a abordar estos problemas y lo que están haciendo durante la pandemia de COVID-19 con las actividades de esta semana.

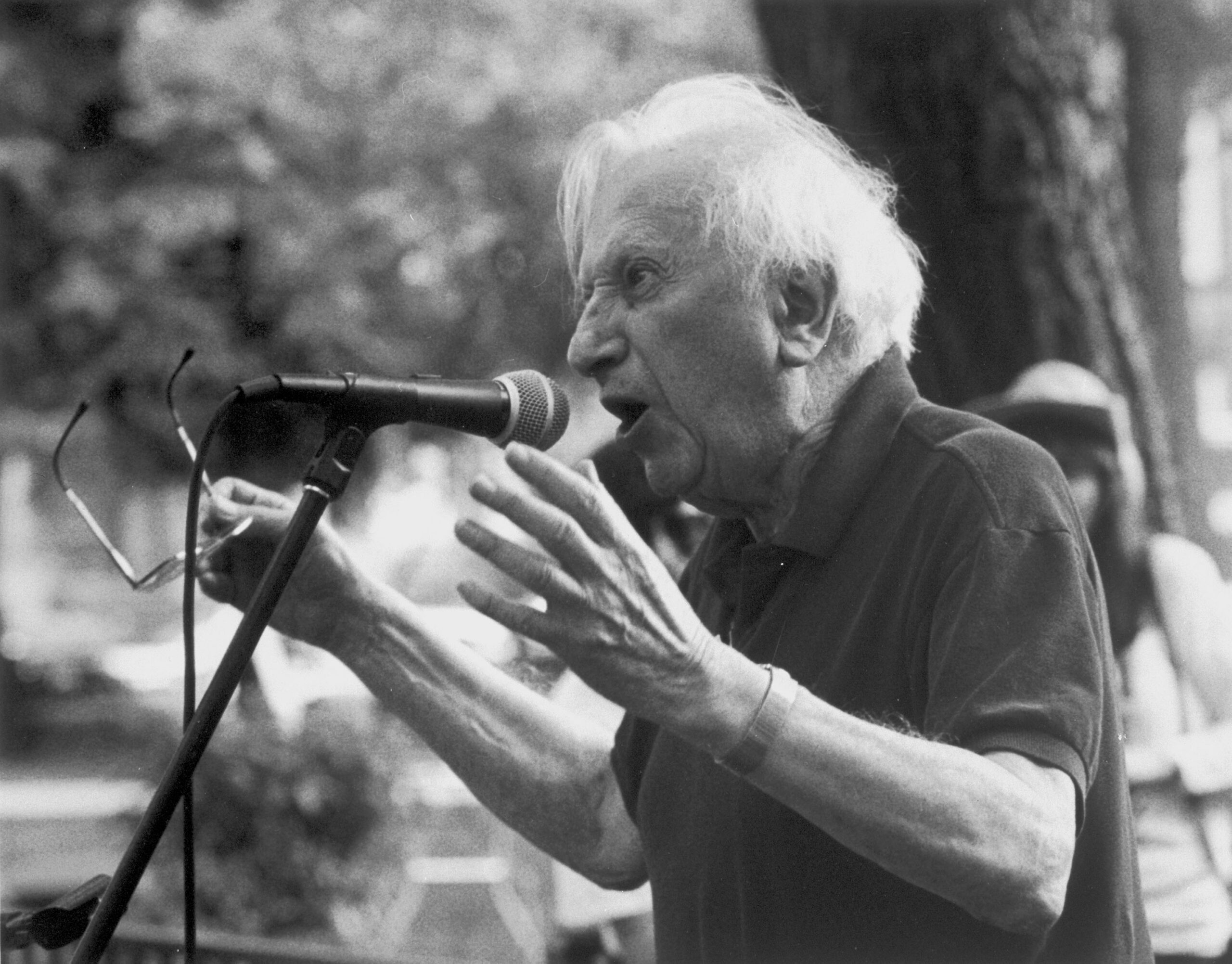

To mark what would have been the 108th birthday of Studs Terkel, Peter T. Alter, CHM chief historian and director of the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, reflects on the memorable moments he shared with Studs at the Museum and Studs’s enduring cultural influence.

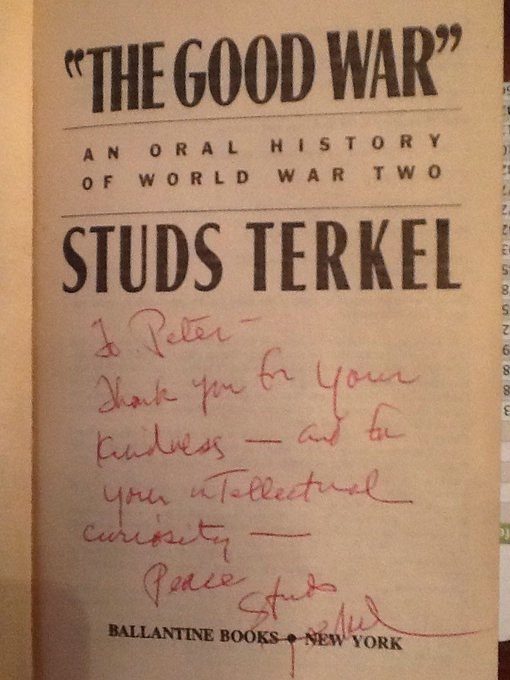

When I started working at the Chicago History Museum in 1999 as a public historian, I knew very little about oral history and museums. I did, however, know who renowned author, actor, journalist, oral historian, disc jockey, and television personality Studs Terkel was. The first Studs book I ever bought was “The Good War”: An Oral History of World War II (1984).

In the 1980s, one of my first trips with my newly minted driver’s license was to buy this Pulitzer prize-winning book at a local bookstore in western Illinois where I grew up. A few years later, I saw Studs speak at the Bughouse Square Debates, a celebration of free speech at Washington Square Park on the North Side.

Studs Terkel making a speech in a park, Chicago, c. 1995. CHM, ICHi-034937

Jumping ahead to my first months at the Museum, I got to know Sylvia Landsman, my department’s volunteer. By that time, Studs was the Museum’s distinguished scholar-in-residence, a position he held from 1997 to about 2005. Sylvia met and became friends with Studs at CHM, and they bonded over the fact that they both attended the University of Chicago in the 1930s. In fact, he thanks her in his book Hope Dies Last: Keeping the Faith in Troubled Times (2004). Sylvia helped Studs mail packages and with other tasks. One day Sylvia wasn’t available, and I stood in for her when he needed help sending a book. For that simple assistance, he signed my copy of the “The Good War.”

Studs’s message reads: “To Peter—Thank you for your kindness—and for your intellectual curiosity—Peace, Studs Terkel.”

Over the following years, I continued to be an eyewitness to Studs. I briefly met Mamie Till Mobley, Emmett Till’s mother, when Studs interviewed her at the Museum. Fourteen-year-old Emmett, a native Chicagoan, was lynched in Mississippi in 1955. I also saw Studs work with the young people of the Museum’s award-winning Teen Chicago project as they developed their own oral history initiative.

CHM’s Teen Council in 2004 with Studs (seated, center) wearing his trademark red socks.

Later, I started to listen to some of the digitized versions of his interviews. I quickly determined that my favorite one was his 1964 interview of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. while the two of them sat at the “bedside” of Grammy award-winning gospel singer Mahalia Jackson at her South Side home. When I listen to Dr. King talk with Studs, I can imagine him with his ubiquitous open-reel recorder.

For five years, I worked as the Museum’s archivist in charge of its wonderful archival and manuscript collections, including Studs’s papers. When digging through his files, I found the transcript for his interview of Joe Ciardi, a well-known poet, whom Studs interviewed for “The Good War.” In the transcript, Studs explains the connection between that book and a previous book, Hard Times: An Oral History of the Great Depression (1970). While I was archivist, the Museum acquired the papers of Eliot Asinof, the author of the book Eight Men Out (1963), which details the 1919 Black Sox scandal. Of course, Studs plays sportswriter Hugh Fullerton in the 1988 movie version of Asinof’s book, which means Studs is also mentioned in the Asinof papers.

The transcript for the Ciardi interview with underlined phrases.

When I became the director of the Museum’s Studs Terkel Center for Oral History in 2015, I grew even more curious about his interviewing style. What I use in oral history training sessions is this wisdom from him: “So I think the gentlest question is the best one, and the gentlest is, ‘And what happened then?’” I am constantly using that in my own interviews as we carry forward Studs’s legacy through the oral history center’s collaborative community-based projects. I also enjoy wearing red socks every workday to acknowledge his famous footwear.

Naturally, these eyewitness-to-Studs moments continue even during the pandemic. My daughter Lily recently finished her first year as a vocal jazz major at Western Michigan University. What did she watch as she finished the second semester from home? Of course, she watched Ken Burns’s documentary series Jazz (2001), featuring multiple interview excerpts of Studs. In April, Friedrich Von Steuben Metropolitan Science Center history teacher Meghan Thomas emailed me about her students conducting pandemic-related oral histories to replicate Studs’s interviews in Hard Times. Just recently, I saw a reference to him in a Chicago Magazine article about the city’s labor history.

Over the years, dozens of people have told me their eyewitness-to-Studs-stories. Many remember listening to his program on WFMT or watching him on television. Others have ridden the CTA with him or waited at the same bus stop. A journalist told me about a chance encounter he had with Studs that changed his entire career trajectory. Some people remember Studs interviewing friends or family or meeting him at book signings and other events. Today, all of us can pick up his books or listen to his recordings. What are your eyewitness-to-Studs stories?

Additional resources

- Listen to the Studs Terkel Radio Archive

- See our images of Studs Terkel

- Learn more about oral history

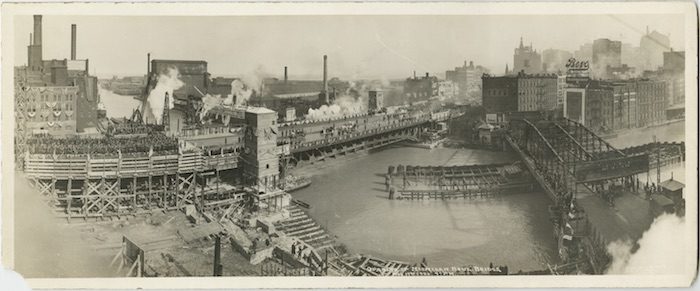

Panorama of the Michigan Avenue bridge during its opening-day parade and celebration, Chicago, May 14, 1920. CHM, ICHi-000144

At 4:00 p.m. on the sunny afternoon of May 14, 1920, a cowboy hat-wearing mayor William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson cut the ribbon to open the upper level of the new Michigan Avenue bridge. Fireworks were shot into the sky, planes dropped booster literature, boats in the river sounded their whistles, and a band played “The Star-Spangled Banner.” During the festivities, workers on the trunnion bascule bridge’s uncompleted lower level remained busily on the job.

Opening of Michigan Avenue Bridge, Chicago, May 14, 1920. CHM, ICHi-029306; J. Sherwin Murphy, photographer

Since then, the bridge has become a frequently-used roadway and has evolved into the structure that you see today. Bas-relief sculptures depicting scenes from Chicago’s early history were installed in 1928. The bridge is considered a structure of primary significance in the Michigan–Wacker Historic District, which was listed as on the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. It was designated a Chicago Landmark in 1991, and in 2010, it was officially renamed the DuSable Bridge in honor of Chicago’s first permanent resident, Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, whose homesite is next to the north end of the bridge.

View of the Michigan Avenue Bridge over the Chicago River, July 20, 1970. The Marina Towers are visible. The IBM building is under construction. CHM, ICHi-068313; Betty Hulett, photographer

The Michigan Avenue bridge was first conceptualized in Daniel H. Burnham’s Plan of Chicago, one of the most noted documents in the history of city planning. Connecting Michigan Avenue with the section north of the river (then called Pine Street) was an extremely complicated proposition, and not only from a design and engineering standpoint. Implementation required the approval of different city authorities, condemnation of various properties next to it, and appropriate legislation. Learn more about Burnham’s vision for reshaping the city and how Michigan Avenue fit into it.

You can see photographs from our collection in the Magnificent Mile Association‘s video celebrating the 100th anniversary of the bridge’s opening day.

In this blog post, CHM curatorial intern Brigid Kennedy recounts the life of Irene McCoy Gaines as part of a series in which we share the stories of local women who made history in recognition of our online experience: Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.

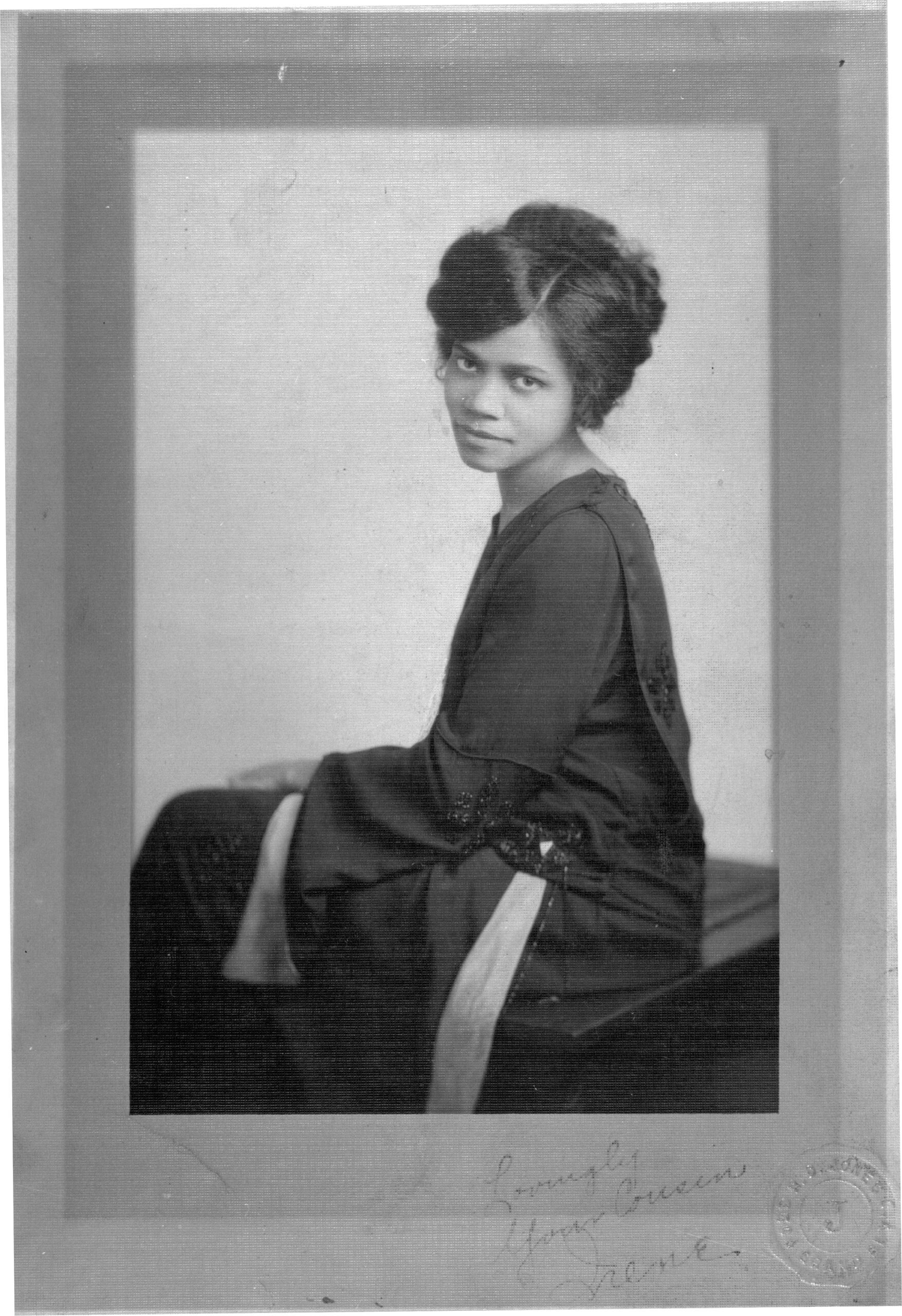

Irene McCoy Gaines devoted her career in politics and advocacy to working against segregation and for the rights of black women. Gaines was born on October 25, 1892, in Ocala, Florida, but moved with her mother to Chicago when her parents divorced. After graduating from high school, she attended Fisk School (a private historically black university, today Fisk University) in Nashville, Tennessee. She graduated in 1910, and years later would continue her studies in social work at the University of Chicago.

Figure 1: Seated portrait of Irene McCoy Gaines. CHM, ICHi-062416

Upon her return to Chicago after college, she discovered that despite her advanced education, job opportunities were severely limited by the discrimination she faced as a black woman. After working as a housekeeper, Gaines found a job as a stenographer at Cook County Juvenile Court. These two early jobs informed her activism for the rest of her life.

Gaines became a member of the Women’s Trade Union League, a national association that supported women in organizing labor unions and improving working conditions, and she recruited other black women for the organization.

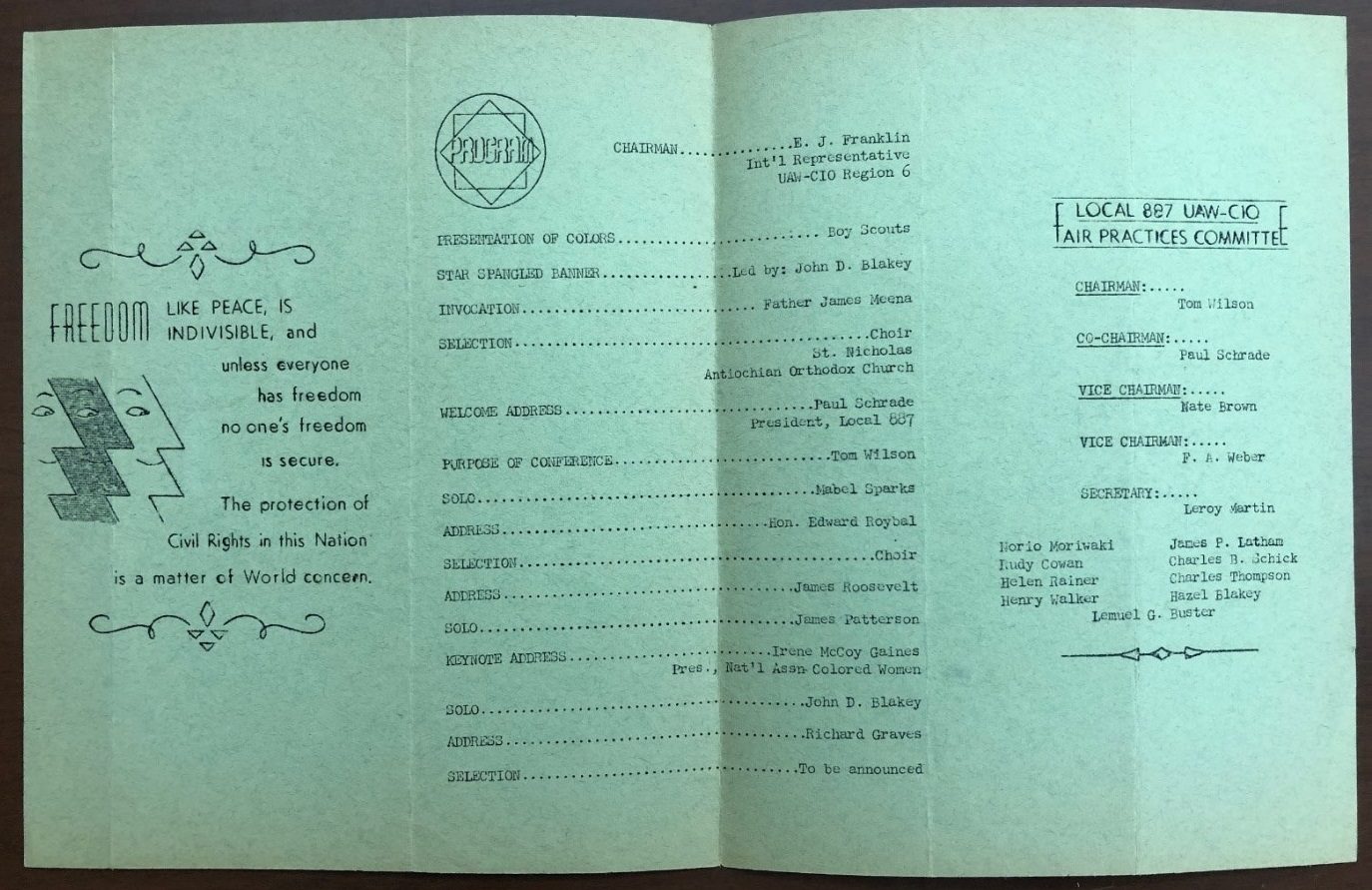

Figure 2: Program for the Local 887 United Auto Workers-Congress of Industrial Organizations Fair Practices Committee Program for Civil Rights & Anti-Discrimination on Sunday, May 2, 1954, at which Gaines delivered the keynote address. Irene McCoy Gaines papers, CHM. Box 4, folder 1.

In 1917, during World War I, she became director of the Girls’ Work Division of the War Camp Community Service program, which connected civilians and soldiers at social events and soldiers to entertainment opportunities in American cities.

Gaines was devoted to the Republican Party of the time, organizing for congressional Republican candidate Ruth Hanna McCormick in 1928 and 1930. She also helped to found and served as president of the Illinois Federation of Republican Colored Women’s Clubs.

In 1931, Gaines was appointed to President Herbert Hoover’s National Committee on Negro Housing, which led to construction of the Ida B. Wells Homes public housing project in the Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. Gaines herself ran for elected office several times unsuccessfully, often the first black woman to run for a particular office, including for a state legislative seat and for county commissioner’s office, which opened doors for others after her.

Figure 3: Irene McCoy Gaines. CHM, ICHi-030640

Gaines tirelessly advocated for the rights of black women—connecting domestic workers to literacy classes and attempting to overturn unjust convictions of women like Adelaide Lauretta Johnson, who was incarcerated for writing checks with insufficient funds. She worked, too, to ensure that pregnant teenagers had opportunities to continue their educations.

In 1941, Gaines, then president of the Chicago Council of Negro Organizations (CCNO), led a trip to Washington, DC. Members lobbied elected officials and protested racial discrimination in employment and by the Federal Housing Authority, US military, and other governmental organizations. After CCNO’s and other’s activism, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, which was intended to prevent racial discrimination in employment by businesses that held government contracts.

Gaines also was interested in promoting arts and culture. She became a lifetime member of the Art Institute in the late 1920s and founded the “Negro in Art Week” program to support black children who were interested in the arts.

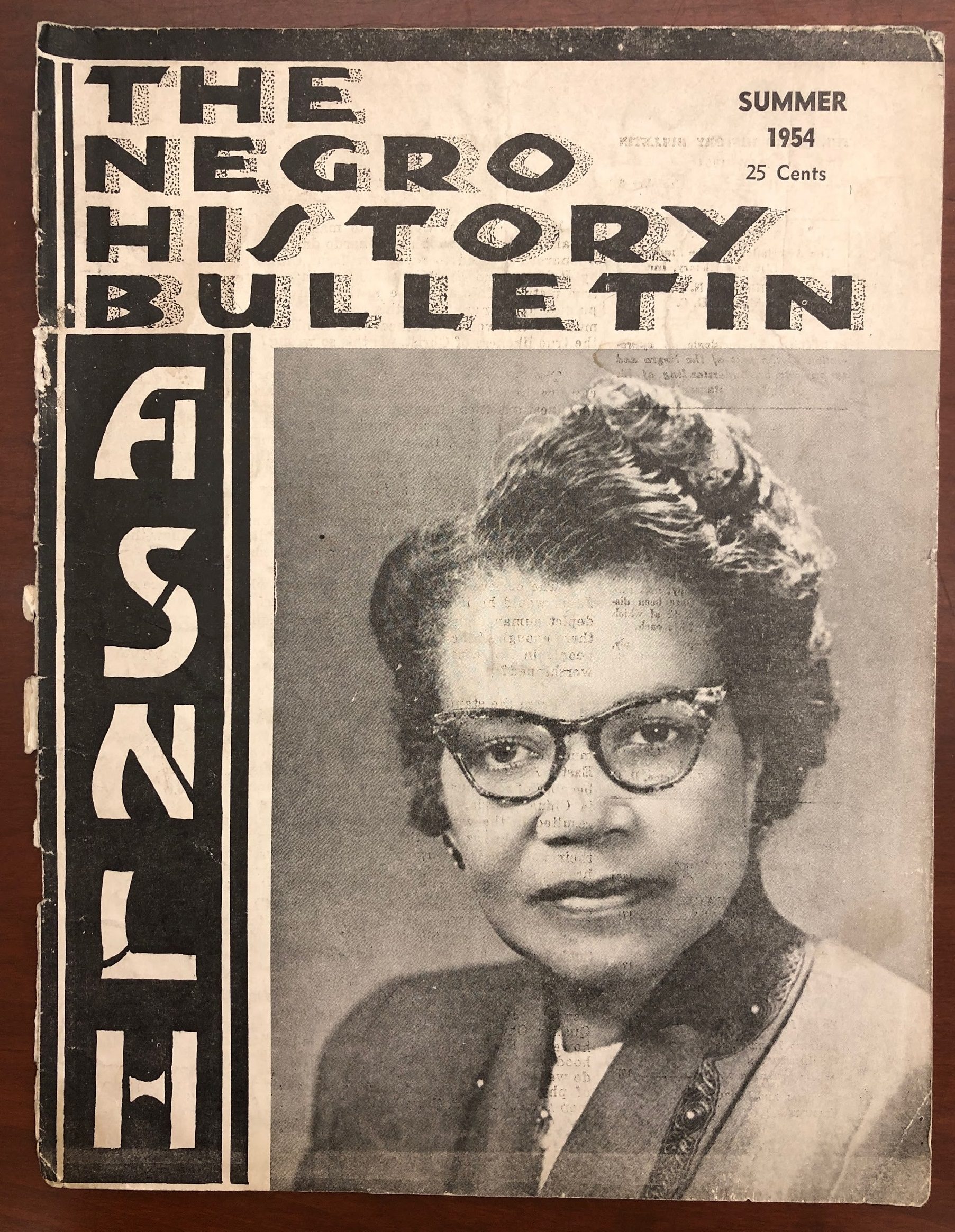

Figure 4: Gaines on the cover of the summer 1954 issue of The Negro History Bulletin. Irene McCoy Gaines papers, CHM. Box 4, folder 1.

In 1953, Gaines co-produced a documentary short about Frederick Douglass, The House on Cedar Hill. It honored among his accomplishments his dedication to women’s rights, and the film won a Freedoms Foundation Award. Gaines died of cancer on April 7, 1964, at age seventy-two, leaving behind a legacy of political and reform work that created new opportunities for black women in Chicago and the nation.

For Educators

Student Reading and Response Guide

Vocabulary

- Advocacy: public support for a cause or policy

- Segregation: the enforced separation of different racial groups

- Discrimination: the unjust treatment of people on the grounds of race, age, gender, or sexual orientation

- Stenographer: a person whose job is to write down speech in shorthand, for example testimony in court

- Indivisible: unable to be divided or separated

Text Questions

- Why do you think working as housekeeper and as a stenographer for Cook County Juvenile Court informed Gaines’ activism?

- What are some examples in the blog of how Gaines worked to end segregation and advance the rights of black women?

- Why do you think Gaines saw the arts as an effective way to communicate the issues she cared about?

Primary Source Analysis: Take a closer look at Figure 2 to answer these questions.

- What 1954 event is this program from? What was Gaines’ role? Why do you think Gaines would have wanted to support this organization?

- This quote appears on the cover of the program: “Freedom like peace, is indivisible, and unless everyone has freedom no one’s freedom is secure.” Do you agree or disagree with this idea? Why? What freedom or civil rights issues are important today?

Journal Prompt

- The blog author, Brigid Kennedy, writes “Gaines herself ran for elected office several times unsuccessfully, often the first black person or black woman to run for a particular office, which opened doors for others after her.” Who has opened doors for you, in your life? How?