Latest Posts

On September 30, 1990, the Chicago White Sox played their final game at Comiskey Park.

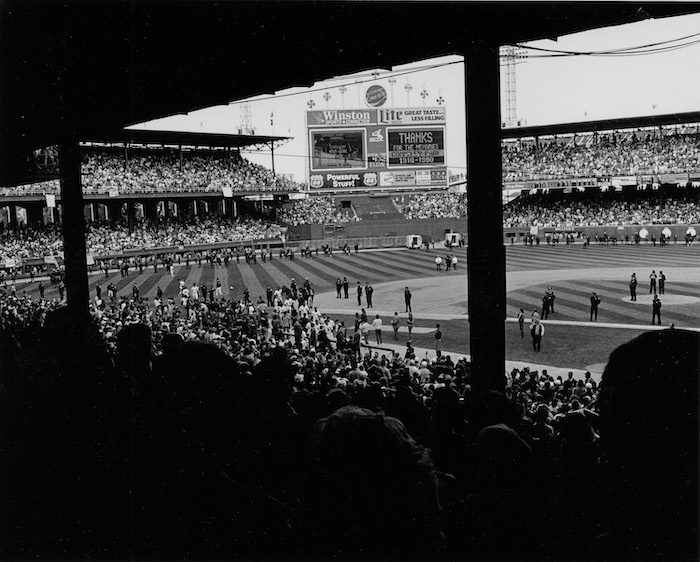

Police guarding the field at the final game at Comiskey Park, Chicago, September 30, 1990. CHM, ICHi-052133; Melody Miller, photographer

Designed by Zachary Taylor Davis, the fireproof steel and concrete stadium, which replaced the all-wooden South Side Park, was located at 35th Street and Shields Avenue and built on a former city landfill. The stadium was originally named White Sox Park but was renamed a few years later after White Sox owner Charles Comiskey. The park was known for being pitcher-friendly, thanks to design input from hall of famer Ed Walsh, with dimensions of 362 feet down the right and left field lines and 440 feet to deep center field. In its eighty years, not a single player hit 100 career home runs there. Carlton Fisk holds the record with ninety-four.

Comiskey Park during construction, 1910. SDN-008841, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Comiskey Park hosted more than 6,000 Major League games and four World Series, including the 1918 World Series between the Chicago Cubs and Boston Red Sox (because its seating capacity was larger than that of Wrigley Field, then known as Weeghman Park). It was the site of the first Major League Baseball All-Star Game in 1933 in conjunction with the A Century of Progress International Exposition. During that game, Babe Ruth hit the first ever MLB All-Star home run. The park also hosted many of the East-West Negro League All-Star games from 1933 to 1962.

Comiskey Park during a game, c. 1910. CHM, ICHi-019088; Barnes-Crosby Company, photographer

In addition to the White Sox, the Negro American League’s Chicago American Giants played home games there from 1941 through 1950. The NFL’s Chicago Cardinals and two North American Soccer League teams (the Mustangs and the Sting) also called Comiskey home. The stadium also served as a concert venue, hosting musical acts including The Beatles, AC/DC, and The Jacksons.

The venue underwent numerous numerous cosmetic and seating capacity changes over the years, including the famous “exploding” scoreboard, installed in 1960 by then-owner Bill Veeck. The 130-foot scoreboard included lights, sirens, a message board, and the iconic pinwheels. The sound effects, strobe lights, and fireworks went into action whenever a White Sox player hit a home run. By 1971, Comiskey Park was the oldest park still in use in the Major Leagues.

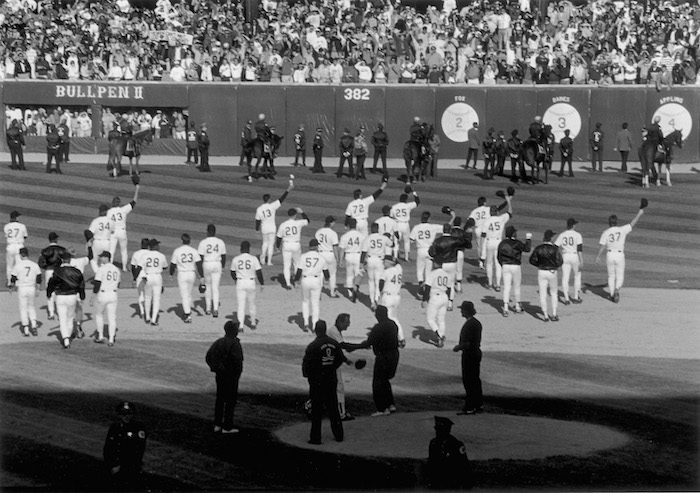

On September 30, 1990, a crowd of 42,849 attended the ballpark’s final game—a 2–1 Sox victory over the Seattle Mariners. Charles Comiskey, former White Sox vice president and grandson of the park’s namesake, was in attendance. Former All-Star left fielder Minnie Miñoso brought the lineup card to the umpires before the game, and at the end organist Nancy Faust played a final rendition of “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye.”

The Chicago White Sox baseball team waves farewell to fans after the final game at old Comiskey Park, Chicago, September 30, 1990. CHM, ICHi-035694; Melody Miller, photographer

A new park, now named Guaranteed Rate Field, was constructed directly across 35th Street, and Comiskey Park was demolished in 1991 and turned into a parking lot to serve the new park. The existence of Old Comiskey is remembered with its field and foul lines painted on the lot and a marble plaque where home plate was once located.

Additional Resources

In light of the recent news that the Palmer House Hotel faces a $338 million foreclosure suit, CHM staff members take a look back at its three iterations.

The Palmer House Hotel was long the pinnacle of grandeur and luxury in Chicago and was for decades the hotel of choice for visiting presidents, dignitaries, and businesspeople. The crown jewel in the holdings of department store mogul turned real-estate developer Potter Palmer, it was a wedding present to his wife, Bertha.

The First Palmer House (1870)

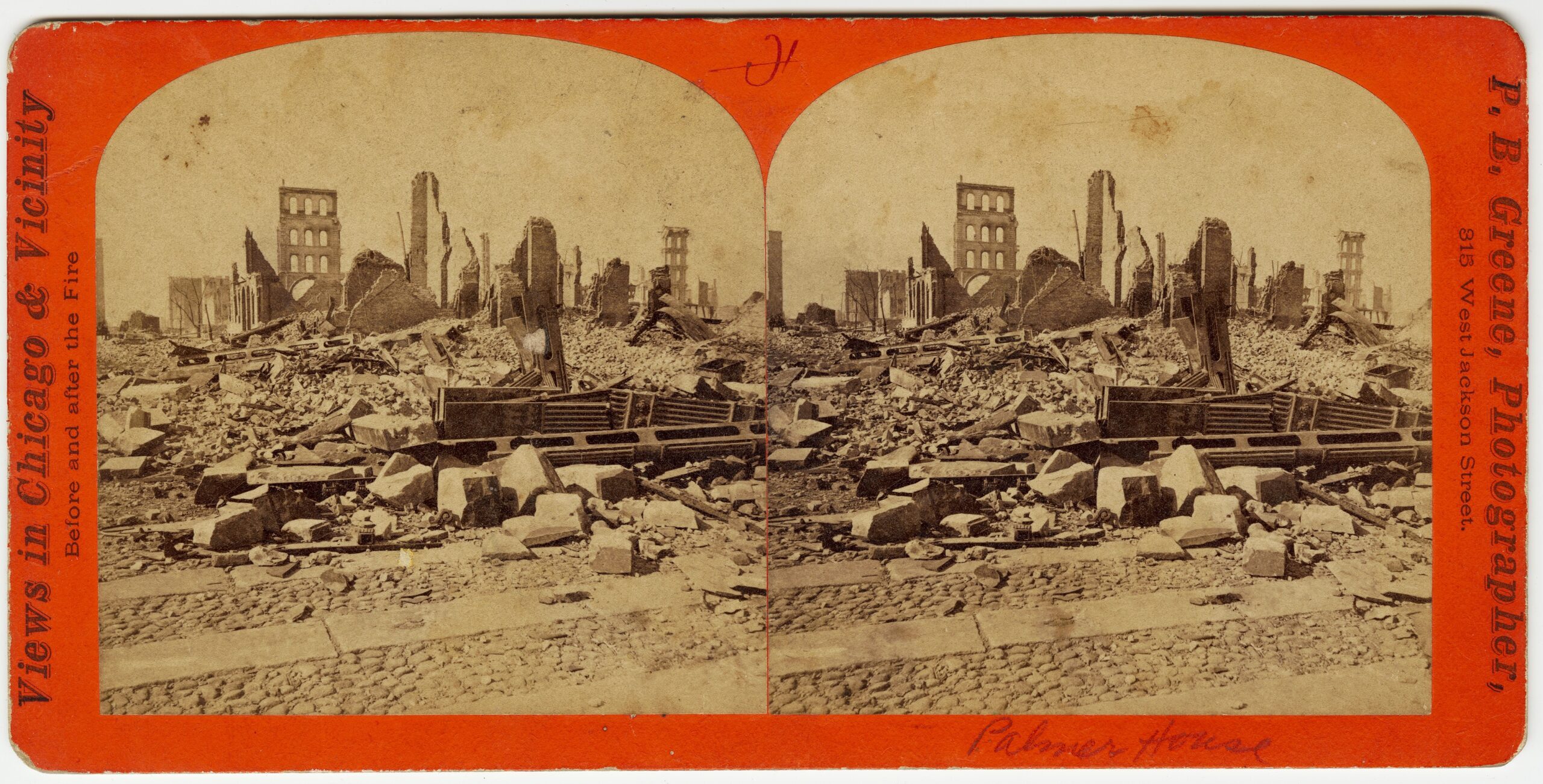

On September 26, 1870, the first Palmer House opened for business at State and Quincy Streets. With 225 rooms, its furnishings alone cost $100,000, or half the construction cost. An additional Palmer House was under construction nearby, but both structures were destroyed by the Great Chicago Fire on October 8, 1871.

A stereograph of the Palmer House ruins after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. CHM, ICHi-026749; P. B. Greene, photographer

The Second Palmer House (1873–1923)

Palmer quickly rebuilt on the same site, employing calcium lights so workers could press on through the night. The resulting seven-story, $13 million hotel designed by architect John M. Van Osdel opened on November 8, 1873, marking the start of what became known as the nation’s longest continually operating hotel.

An engraving entitled “Working at Night on Palmer’s Grand Hotel, by Calcium Light,” 1871. CHM, ICHi-002930

The hotel was filled with Italian marble and rare mosaics and was so ornate that it was alternately mocked and praised. Like many Chicago buildings in the late nineteenth century, the Palmer House claimed to be fireproof.

An albumen print of the second Palmer House Hotel, Chicago, c. 1885. CHM, ICHi-069676; J. W. Taylor, photographer

The Palmer House not only served transient visitors but also appealed to wealthy permanent residents who found in the palace hotel a convenient way to set up trouble-free, elegant households.

The ladies’ entrance to the Palmer House hotel, which can be seen in the lower left corner of the albumen print, Chicago, September 19, 1903. DN-0001231, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

This ornate headboard (1873) on the right was part of a bridal suite in the second Palmer House. Made of ebonized and gilded black walnut in a Renaissance style, the headboard was surmounted by a French-style canopy. It was made by W. W. Strong Furniture Co., Chicago’s premier furniture dealer and manufacturer of the 1870s. You can find it on display in Chicago: Crossroads of America.

The Third Palmer House (1925–present)

The economic boom and population growth of the 1920s and Chicago’s increasing attractiveness as a convention city led to a perceived shortfall in hotel rooms. Thus, the Palmer Estate decided to raze the Palmer House for a new $20 million rendition on the same site. Designed by the firm Holabird & Roche and built during 1923–25, its twenty-five stories housed 2,268 rooms and for a very short time held the record as the world’s largest hotel.

The current Palmer House hotel under construction, 17 East Monroe Street, Chicago, c. 1925. HB-05894-M, CHM, Hedrich-Blessing Collection

As with many luxury hotels, the Palmer House boasted a grand lobby, monumental staircases, bridal suites, dining rooms, ballrooms, a bar, and a barbershop.

The barbershop at the Palmer House Hotel, Chicago, c. 1930. CHM, ICHi-080559; Raymond W. Trowbridge, photographer

An eager crowd at the Palmer House Bar waits to be served upon the repeal of Prohibition, Chicago, 1934. DN-A-4938, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

In 1933, Palmer House converted its Empire Dining Room into an entertainment venue and supper club. Before air travel was common, Chicago was a popular stopping point for celebrities traveling by train between New York and Los Angeles, and the Palmer House saw its share of big-name entertainers, including Frank Sinatra, Judy Garland, Ella Fitzgerald, Harry Belafonte, Louis Armstrong, and Liberace.

The Empire Room at the Palmer House Hotel, Chicago, c. June 4–8, 1936. HB-03386-C, CHM, Hedrich-Blessing Collection

While its hotel rooms are standard upscale fare, the Palmer House’s palatial lobby, conceived as a European drawing room, remains one of the most magnificent in the world.

View of the Great Hall Lobby from the Empire Room at the Palmer House, Chicago, 1925. CHM, ICHi-038783

An undated postcard of the third Palmer House Hotel, Chicago. CHM, ICHi-069672

Eclipsed in the 1980s by posh hotels on North Michigan Avenue closer to fine shopping, the Palmer House—a part of the Hilton Hotel chain since 1945—continued to attract guests because of its proximity to the Loop business district, the Art Institute of Chicago, and downtown theaters.

Head into costume storage with CHM costume collection manager Jessica Pushor as she discusses the iconic costume pieces that came out of the partnership between dancer and choreographer Ruth Page and artist Isamu Noguchi.

Ruth Page (1899–1991) was a legendary ballerina and innovative choreographer. She was the first American guest ballet soloist with the Metropolitan Opera, and she brought world-class dance to Chicago’s stages as artistic director of the Chicago Opera Ballet, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and The Ravinia Festival. Her legacy continues to be celebrated in Chicago through the Ruth Page Foundation, which oversees the Ruth Page Center for the Arts.

Page donated nearly one hundred dance costumes, designer dresses, and accessories to the Chicago History Museum’s costume collection. Many of the Museum’s earliest and most breathtaking Christian Dior garments were worn by Page and were featured in past CHM exhibitions Dior: The New Look (2006) and Chic Chicago: Couture Treasures from the Chicago History Museum (2008). However, it is her dance costumes that are thought to be some of the most culturally significant artifacts she donated to the Museum.

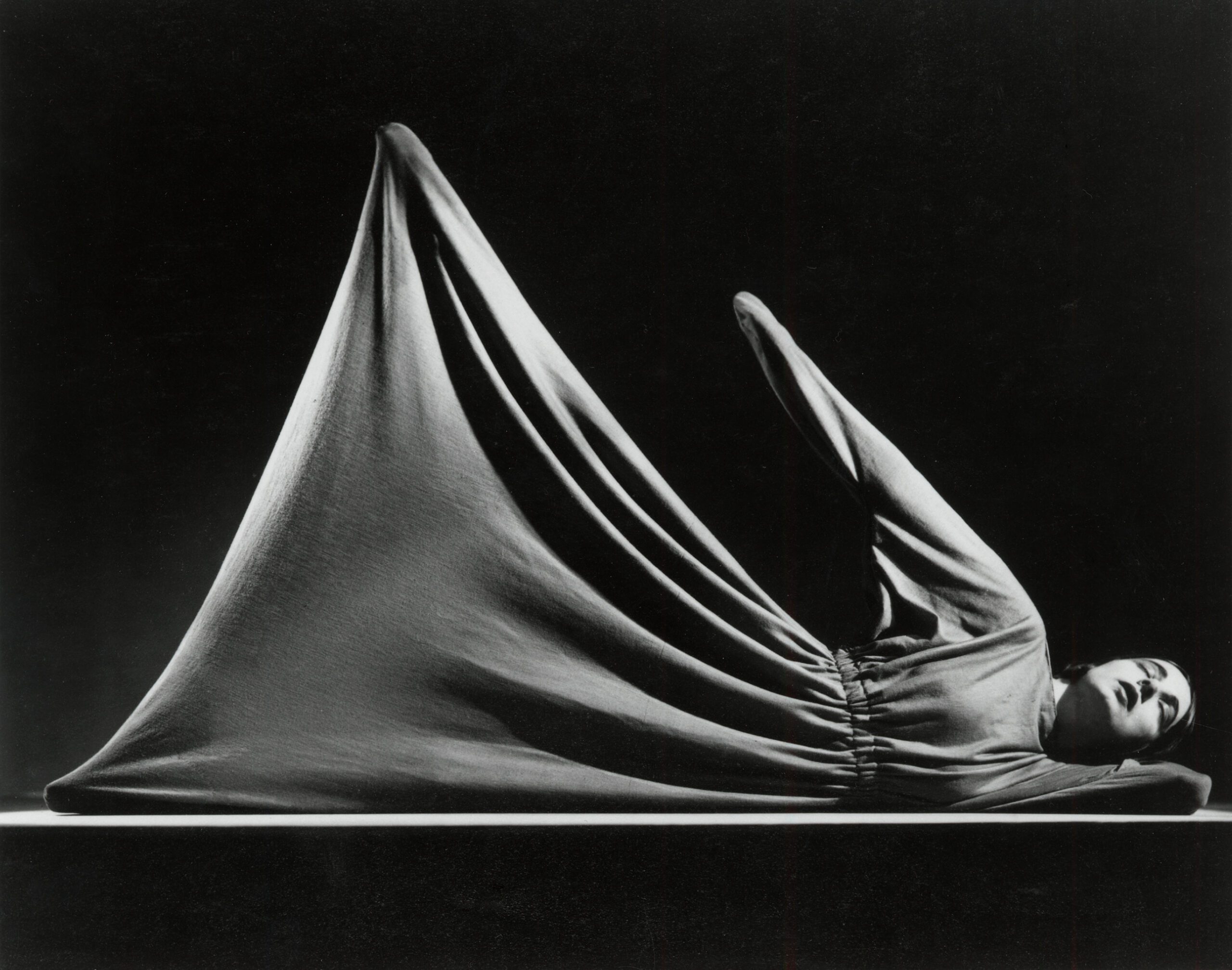

An undated photograph of Ruth Page in one of her costumes for Expanding Universe. CHM, ICHi-031053

In 1932, Ruth Page began a personal and professional relationship with Japanese American artist Isamu Noguchi (1904–88). During their collaboration, Noguchi created two blue wool sack costumes for Page. The forms and shapes she created in these costumes by stretching and contouring the fabric with her body would be forever memorialized by Noguchi in ink drawings, sculptures, and stunning photographs. Ruth Page would later donate these two iconic sack dresses to the Museum in 1979.

The garment (above) and a close-up of its labels (below). The base of the garment measures about 39 inches.

The first costume, 1979.226.9, has sleeves but no openings for the hands, an elastic waistband, and is closed at the bottom. [Ed. note: This garment is currently on display in Dressed in History: A Costume Collection Retrospective, which closes July 27, 2025.] The only opening is an open slit at the neck. This sack dress is the inspiration for Noguchi’s sculpture Miss Expanding Universe (1932), which Page bequeathed to the Art Institute of Chicago.

Ruth Page was a petite woman, and this garment measures about 51 inches from the stirrups to the top corner.

The other sack dress, 1979.226.10, is rectangle of blue wool with a small slit opening at the top. This costume does not have armholes or sleeves, but has two openings at the bottom with stirrups for the feet. Page wore these costumes in a ballet she choreographed and performed in 1932 called Expanding Universe, which repremiered in 1933 as Variations on Euclid.

The fabric along the garment’s seam shows wear and tear.

Both costumes show wear and have many repairs and patches at the corners where Page pulled, grabbed, and pushed the fabric with her hands and feet. You can see tears along the seams and discoloration from use on each piece. The elastic stirrups have also worn out from use and were replaced by the Museum the last time this object was on view.

Noguchi and Page would collaborate again in 1946 when he designed the costumes and sets for The Bells, a ballet choreographed by Page based on Edgar Allan Poe’s poem of the same name. However, this second project did not create the same iconic artwork and imagery as Expanding Universe. Ruth Page passed away in 1991, and a sketch of Ruth Page by Noguchi in the sack dress is etched on her gravestone in Graceland Cemetery.

Additional Resources

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s 1978 interview with Ruth Page

- Watch Variations on Euclid a.k.a. Expanding Universe, Chicago Film Archives, c. 1938, Ruth Page Collection

- Ruth Page’s papers can be found at the Newberry Library

- Learn more about Page’s work in Chicago in Liesl Olson, “What did a 1930s ballet say about cultural appropriation in modernist Chicago?” Chicago Reader, March 28, 2019.

Missing college football’s annual fall kickoff? We’ve huddled up some images from the first half of the twentieth century. Peter T. Alter, CHM chief historian and director of the Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, provides insights on a time when Chicago-area teams and coaches dominated the collegiate gridiron.

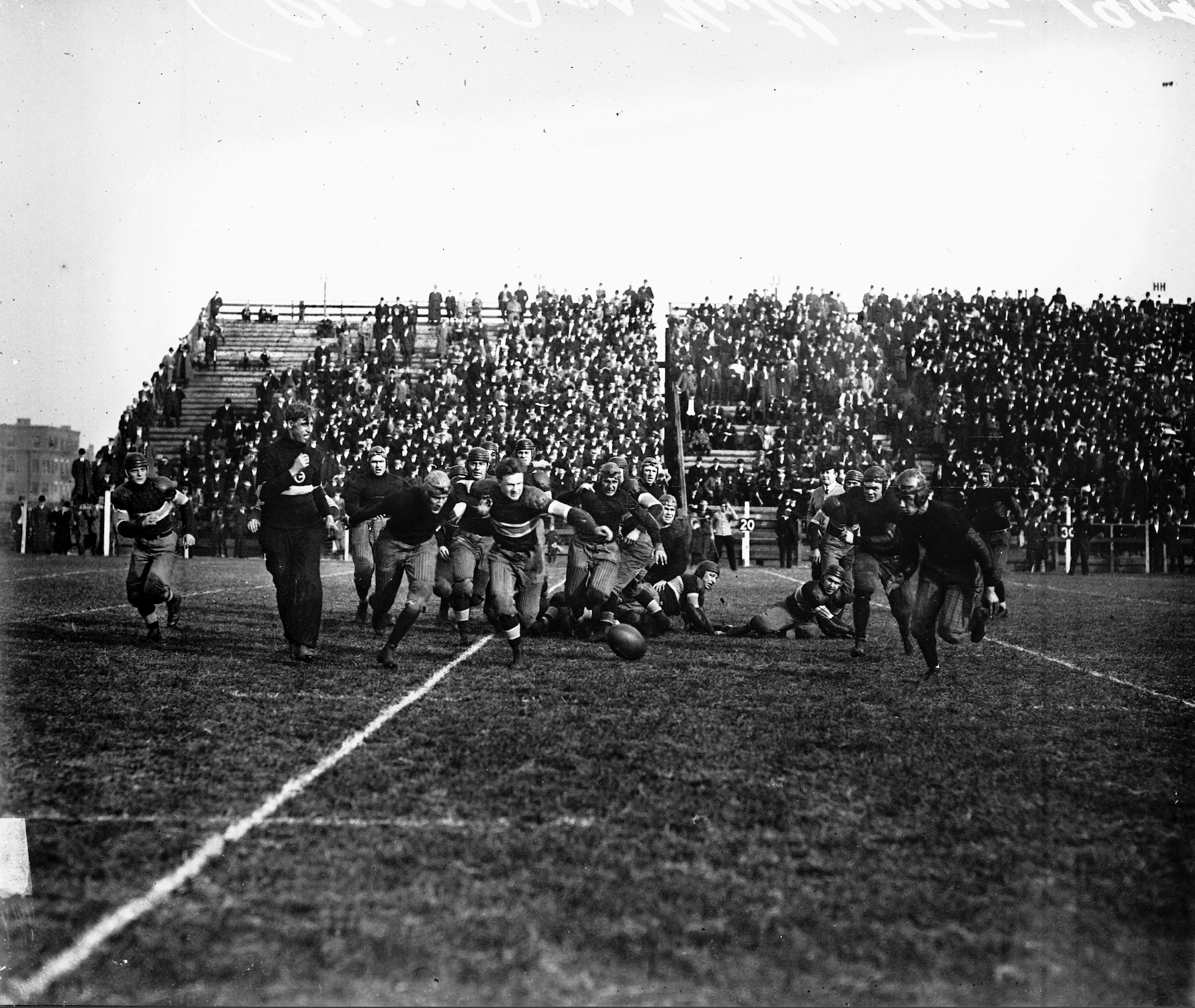

A football game between the University of Chicago and Northwestern University at Marshall Field (renamed Stagg Field) at East 57th Street and South Ellis Avenue on the UChicago campus in the Hyde Park community area, 1909. SDN-055873, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The University of Chicago was an early powerhouse before it nearly punted the sport to focus on academics. The Chicago Maroons were, in fact, the original “Monsters of the Midway,” taking their name from the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition that took place near their campus. The Chicago Bears borrowed this nickname as well as the Old English “C” logo. In 1892, two years after the university’s founding, Amos Alonzo Stagg became the first tenured football coach in the US.

Coach Amos Alonzo Stagg explains plays to his team on a field next to the Henry Crown Field House, Chicago, September 16, 1932. CHM, ICHi-051374

Coach Stagg became hugely successful thanks to the support of university president Robert Maynard Hutchins and his pioneering work as an entrepreneurial and football genius—Stagg created influential formations and plays and led the move toward interregional games and football as mass entertainment. Wealthy Chicagoans would often dress up in their finest, climb into their best carriages, and go watch the Maroons roll over the competition. The Maroons won national championships in 1905 and 1913, and in 1935, halfback Jay Berwanger became the first recipient of the Heisman Trophy (then called the Downtown Athletic Club Trophy).

A bit north in Evanston, Northwestern University saw good times as well, winning Big Ten conference titles in 1903, 1926 (shared), 1930 (shared), 1931 (shared), and 1936 before enduring a fifty-nine-year drought.

A Northwestern University cheerleader at a football game at Dyche Stadium (now Ryan Field), Evanston, Illinois, 1962. CHM, ICHi-175198; Stephen Deutch, photographer

The Northwestern University Wildcat Marching Band on the field at Dyche Stadium (now Ryan Field), Evanston, Illinois, 1950s–1960s. CHM, ICHi-175541; Stephen Deutch, photographer

The Wildcats were led by some notable coaches, such as College Football Hall of Famer Pappy Waldorf (1935–46), Bob Voigts (1947–54), who led them to their first Rose Bowl win in 1949, and Ara Parseghian (1956–63), who later found great success at Notre Dame and was also inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. Outstanding players include All-American quarterback Jimmy Johnson (1904–1905) and future Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback Otto Graham (1941–44).

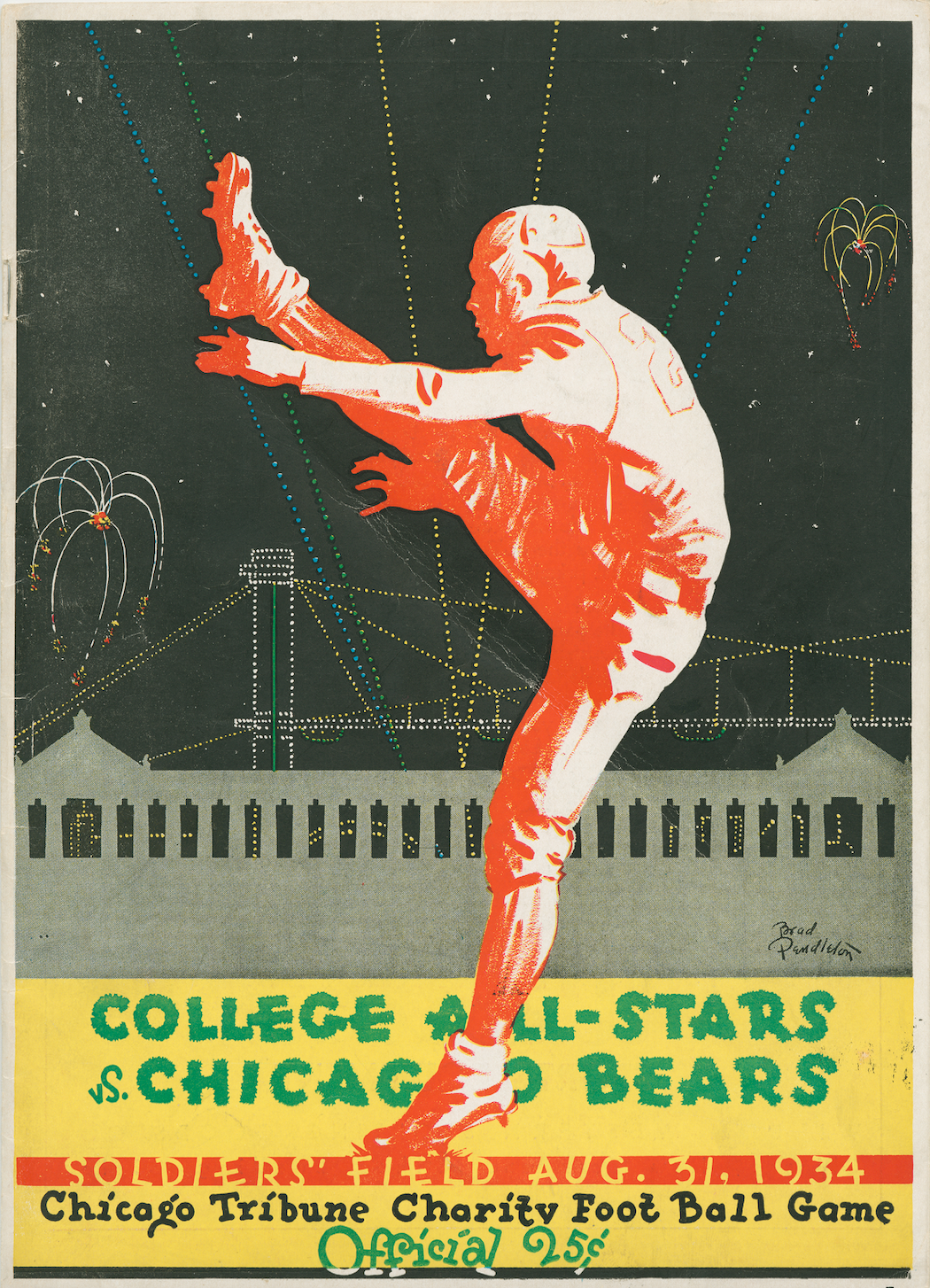

An advertisement for the first College All-Star Football Classic with the College All-Stars vs. Chicago Bears at Soldier Field, Chicago, 1934. CHM, ICHi-036998

In 1934, legendary sportswriter Arch Ward of the Chicago Tribune initiated the College All-Star Game, which was played annually in Chicago through 1976. Matching a team of graduated All-American college players from the previous season against the defending National Football League professional champion, the games were typically played at Soldier Field. The first game took place during the A Century of Progress International Exposition, which is why a dotted outline of the Sky Ride appears on the poster. Future Baseball Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson, a football star at UCLA, played in the 1941 game. During its lifetime, the series raised approximately $4 million for various Chicago-area charities. Since 1997, the Chicago Football Classic, also played at Soldier Field, has featured a clash between two HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) teams with proceeds supporting a scholarship fund.

Additional Resources

- Read more about the history of football in Chicago

- See more images of college football from our collection

To mark Labor Day and Chicago’s long history of labor activism, CHM assistant curator Brittany Hutchinson recounts how the Pullman Company’s porters formed the first all-Black labor union in the US to address low wages, long hours, and mistreatment from passengers.

In August 1925, A. Philip Randolph was elected president the newly formed Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP), the first all-Black labor union in the US. The union initially faced opposition not only from the Pullman Company, but also porters who were fearful of termination and members of the African American community who viewed George Pullman as an ally and credited him with providing lucrative employment opportunities for formerly enslaved men and women.

An undated portrait of A. Philip Randolph. CHM, ICHi-018048

A meeting of the BSCP in an auditorium, 1927. CHM, ICHi-025673

Following the Civil War, George Pullman sought to hire formerly enslaved men as sleeping car porters. The Pullman Company’s decision to hire Black men to serve as porters created an opportunity for economic advancement for newly emancipated African Americans and is often credited with contributing to the creation of the Black middle class. Despite these benefits, Sleeping Car Porters were often mistreated, both by their customers and the company.

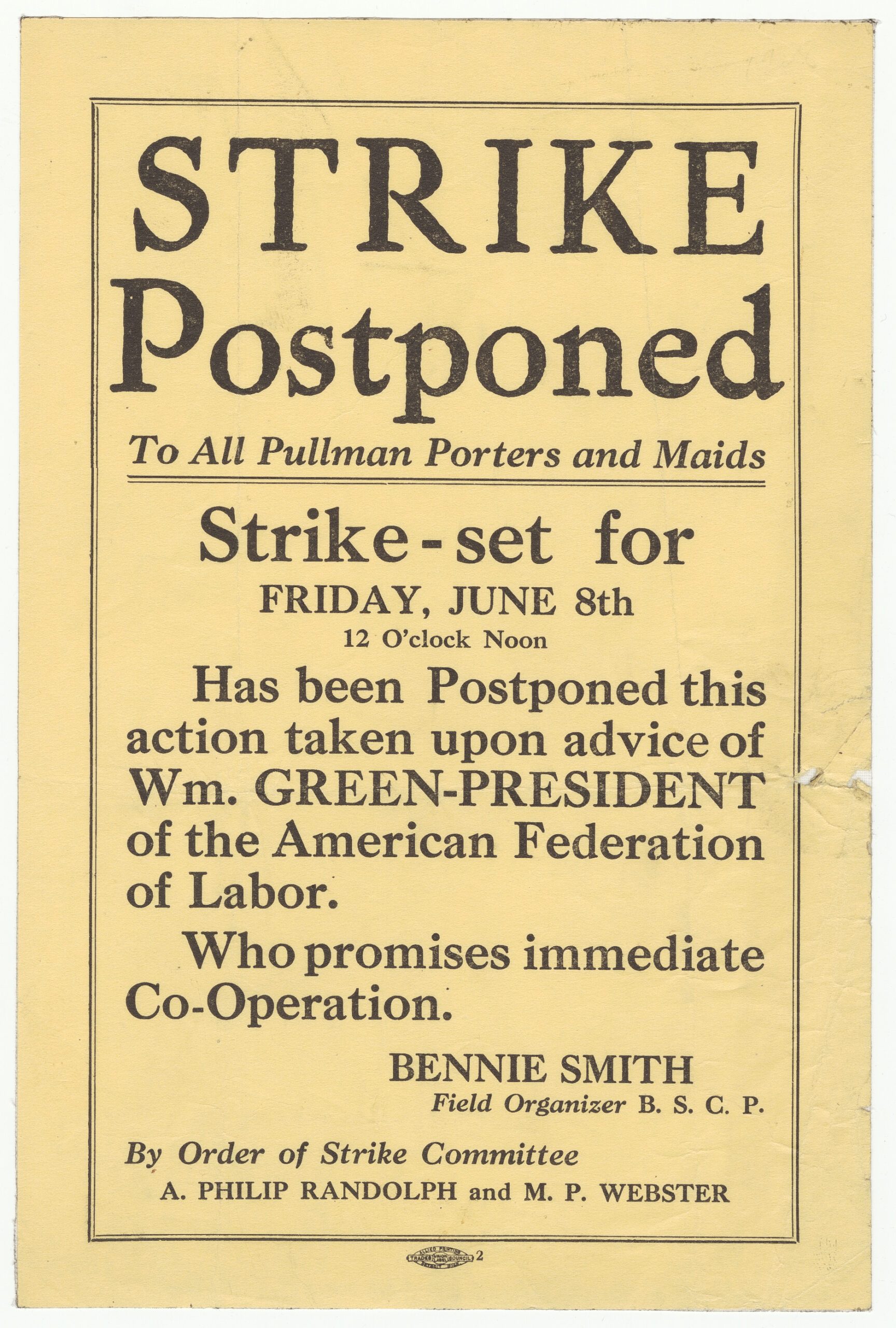

A broadside announcing the postponement of a Pullman porter strike, 1928. CHM, ICHi-061917

While employment as a Pullman Porter was eventually viewed as high-paying job, initially it was not. The wages were very low for the standards of the day, and porters would often need to work at least 400 hours each month to earn their full monthly pay. In comparison to other company roles, porters were paid the lowest salary and had to cater to the passengers’ every whim in order to earn tips. In addition to working long hours and receiving little pay, porters were subjected to unbridled racism. Despite some of the relatively positive outcomes for the Black community, Pullman’s decision to hire formerly enslaved men was rooted in the belief that former slaves would be fully acclimated to servitude and long hours. Passengers commonly referred to porters as “George” regardless of their name, continuing the demeaning practice of calling an enslaved person by their owner’s name. The combination of racism and inhumane working conditions led to calls for unionization.

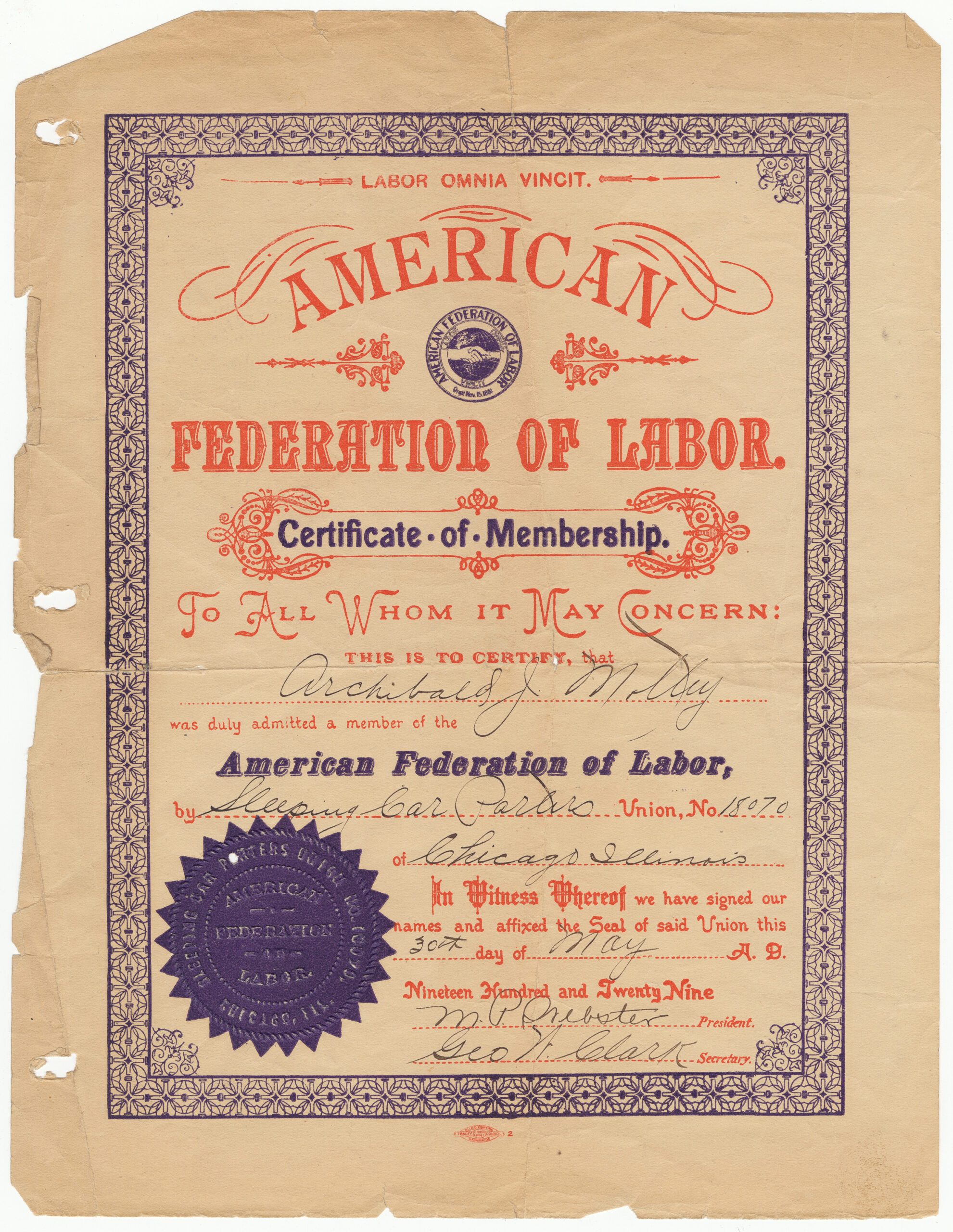

A certificate of membership in the American Federation of Labor through the Sleeping Car Porters for Archibald Motley, father of Harlem Renaissance artist Archibald Motley Jr., 1929. CHM, ICHi-061920

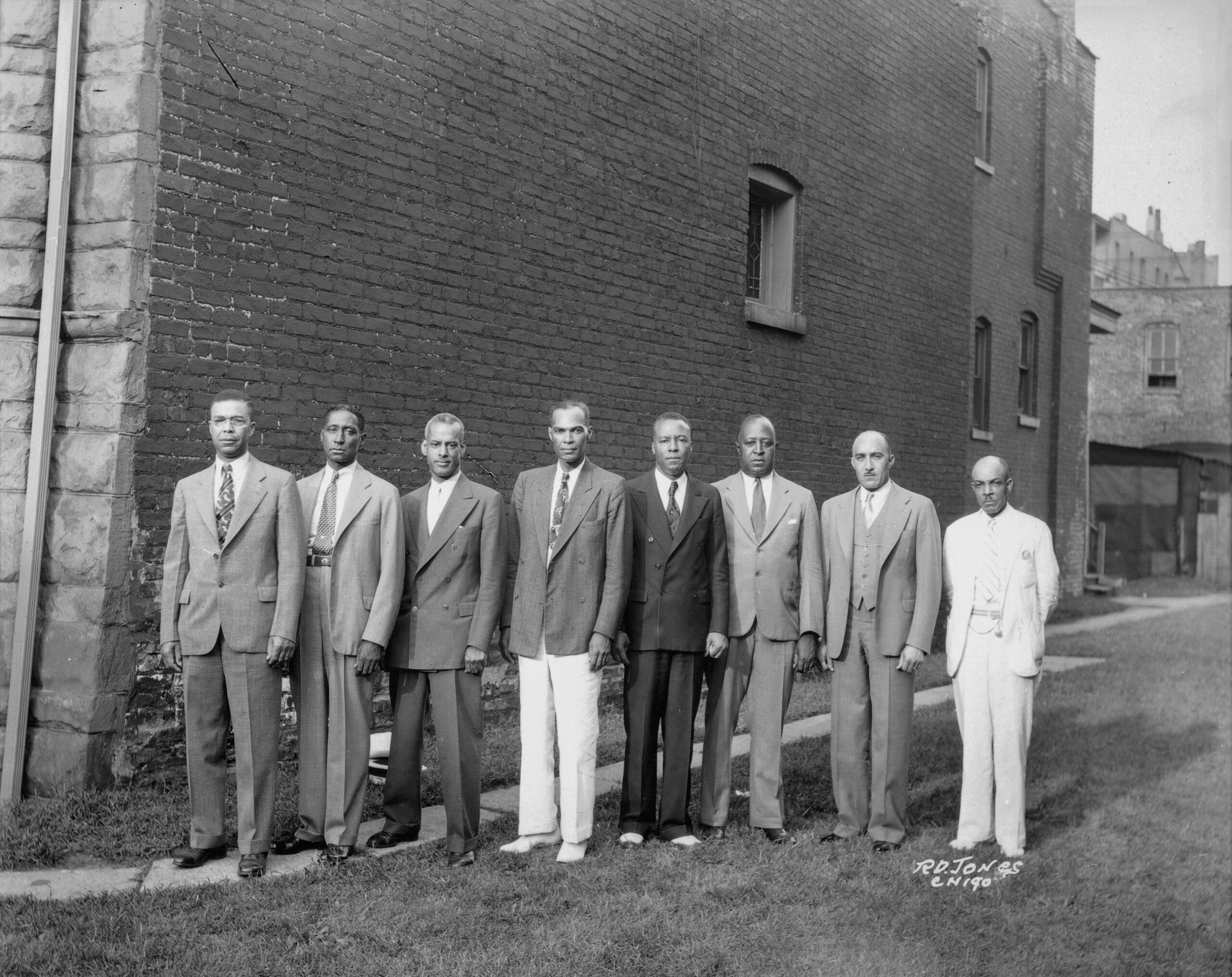

BSCP officers, c. 1935. CHM, ICHi-022642

In 1935, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters became the first African American union organization to be granted membership into the America Federation of Labor. The Pullman Company agreed to negotiations with the BSCP and in April 1937, after twelve years of resistance, a contractual agreement was finally reached which included an increase in wages and a cap of 240 hours per month.

Milton P. Webster, the first vice president and leader of the Chicago division of the BSCP, 1951. CHM, ICHi-024898

The BSCP’s influence in the labor movement included a role in assisting the Great Migration by dispersing information about job opportunities and greater equality for Black people in the North. As the passenger car industry declined after World War II, A. Philip Randolph and the BSCP became early and influential figures in the Civil Rights Movement, as the fight for labor rights is inextricably linked to civil rights.

Additional Resource

“1963 is not an end, but a beginning.”

On August 28, 1963, more than 250,000 protesters gathered in Washington, DC, for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. At that time, it was the largest demonstration for human rights in United States history.

A woman holds a sign that reads: “We march for jobs for all a decent pay NOW!” in a procession at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, DC, August 28, 1963. CHM, ICHi-050226; Declan Haun, photographer

The event has origins in the March on Washington Movement (MOWM), which was led by civil rights activist Bayard Rustin and Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters president A. Philip Randolph. From 1941 to 1946, the organization called for several marches on the nation’s capital to demand for an end to segregation in the armed forces and discrimination in federal hiring practices. The MOWM dissolved by the end of World War II, but not before inspiring new tactics in resistance. Its militant, Black-only format also set a precedent for the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in ideals and methods.

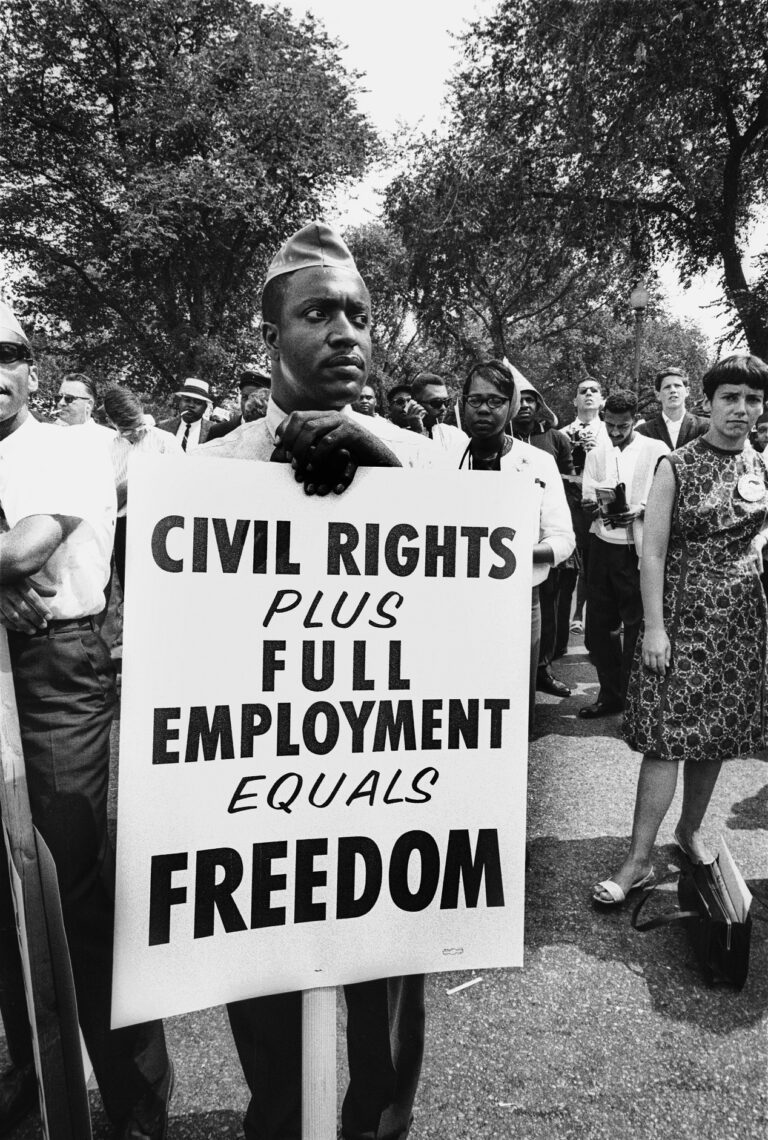

A man stands with a sign that reads “Civil Rights Plus Full Employment Equals Freedom” at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, DC, August 28, 1963. CHM, ICHi-036879; Declan Haun, photographer

By 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had successfully led the Montgomery bus boycott and was beginning his work in Birmingham, Alabama, when Randolph invited him to participate in another March on Washington. This one was meant to protest the widespread lack of gainful and fair employment due to racial discrimination. Rustin and Randolph organized a lineup of speakers and performers that included Mahalia Jackson, Marian Anderson, John Lewis, Bayard Rustin, and Josephine Baker.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks from the Lincoln Memorial to the crowd at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, DC, August 28, 1963. CHM, ICHi-051643; Declan Haun, photographer

From the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Dr. King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, which became one of the most memorable and oft-quoted speeches in recent history. Afterward, Rustin read off a list of demands, which included the creation of a federal job training and placement program, desegregation of all school districts, withholding federal funds from segregated or discriminatory programs, access to all public accommodations, safe housing, and the protection of the right to vote for all Americans.

A man holding a sign that reads “We march for jobs for all a decent pay NOW!” at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, DC, August 28, 1963. CHM, ICHi-079505; Declan Haun, photographer

Following the march, Dr. King met with president John F. Kennedy and vice president Lyndon Johnson to discuss the list of demands and development of civil rights legislation. The years following the march saw some of that legislation come to pass. It was after Kennedy’s death that president Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, much of which addressed many of the march’s demands. Listen to Dr. King’s Speech.

Studs Terkel Radio Archive

In October 1964, Studs Terkel interviewed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Chicago at the home of their mutual friend, gospel singer Mahalia Jackson. They discussed Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech that he made just a little more than a year prior in Washington, DC, how his father’s views influenced his work, and the injurious effects of segregation. Listen to the interview.

In this blog post, CHM curatorial intern Divya Pai recounts the work of Lucy Hyde Ewing and Madeline Upton Watson as part of a series in which we share the stories of local women who made history in recognition of our online experience: Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.

The fight for women’s suffrage in Chicago started in the 1860s and saw victory in 1913 when the Illinois legislature passed a bill that was supposed to give all women the right to vote in local and presidential elections. The work continued for passage of a constitutional amendment that would grant women suffrage nationwide.

The Silent Sentinels were a group of suffragists organized by the National Woman’s Party (NWP) who began picketing outside the White House on January 10, 1917, in response to president Woodrow Wilson’s dismissive suggestion that they “concert public opinion” about the vote. The Silent Sentinels held signs with messages such as “Mr. President how long must women wait for liberty.”

After daily silent protests and facing antisuffragists who shouted insults, threw fruit, and tore their banners, the first arrests came in June 1917. Two of the women arrested in these protests were from Chicago.

Portrait of Ewing, c. 1915. Photograph by Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress

Lucy Hyde Ewing was born in 1885 in Chicago into a political family. Adlai Stevenson, her first cousin once removed, served as vice president under president Grover Cleveland. The Stevenson family would become a prominent political family in Illinois and at the national level.

Ewing was arrested on charges of obstructing traffic for picketing with a banner. She was among the first groups of protesters to receive an unpardoned prison sentence and served thirty days at Occoquan Workhouse in Lorton, Virginia.

Madeline Upton Watson, who was also born in 1885 in Illinois, served as the treasurer of the Illinois branch of the NWP. She was arrested twice, first for picketing the White House in August 1917 and again in 1918 for her participation in the Lafayette Square meetings, which took place to protest the Senate’s inaction on the proposed suffrage amendment. She served time in Occoquan for both arrests.

August 1917 arrest of White House picketers Catherine Flanagan (left), and Madeline Watson (right). Photograph by Harris & Ewing,Library of Congress

The Chicago Tribune reported that after Watson’s first arrest, she commented, “Three policemen were allotted to protect us from a mob of 3,000 yesterday. Forty policemen were sent out to make arrests today. . . . Trial at 9:30 Saturday morning. We defend ourselves.”

Ewing’s and Watson’s treatment at Occoquan is described in Jailed for Freedom by Doris Stevens, who herself served three days. Ewing was among the women whose mail was withheld and read by prison matrons, while Watson was allowed a single letter, likely because she had a ten-year-old child. The prisoners were given a diet of unsanitary drinking water, sour bread, and rancid soup and made to perform prison work. Those who refused were put in solitary confinement.

Word of these poor conditions at Occoquan reached Illinois senator J. Hamilton Lewis, who traveled to Virginia to visit Watson and Ewing. After seeing the conditions, he was reported to have said: “I have never seen prisoners so badly treated, either before or after conviction.” Though he offered to negotiate for their release, all the imprisoned women said they would rather stay at Occoquan for a year than cease picketing and give up their cause.

Madeline Watson (far left) and Lucy Ewing (far right) with a group of suffragists, c. 1917. Photograph by Harris & Ewing, Library of Congress

In February 1919, Ewing went on the “prison special” tour while serving as chairman of the NWP. She wore her prison uniform and gave speeches on voting rights and her experience in Occoquan.

Following ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, the NWP turned its fight toward full constitutional equality for women and continues to provide education on the women’s rights movement.

For further reading

- Online Biographical Dictionary of Militant Woman Suffragists, 1913–1920

- Women Suffrage Prisoners at Occoquan Workhouse, Occoquan Regional Park

For the past ninety-one years, one of Chicago’s back-to-school traditions has been the Bud Billiken Day Parade, which passes through the historic South Side neighborhood of Bronzeville and concludes with a picnic in Washington Park.

In 1923, Chicago Defender founder Robert S. Abbott and his managing editor, Lucius Harper, formed the Bud Billiken Club. Abbott had long expressed a concern for Chicago’s African American youth, and the success of the Defender‘s “young people’s page” convinced him that a club would also be popular. Harper apparently chose the name “Bud” because it was his own nickname, and “Billiken” because of its association with an ancient Chinese mythical character believed to be the guardian angel of all children.

The float for the Bud Billiken Day Parade king, queen, and court, August 10, 1968. ST-40001296-0010, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; Bob Black, photographer

By 1929, the Bud Billiken Club, with its membership cards and identification buttons, was so popular among Chicago’s Black youth that Abbott decided to initiate an annual parade to celebrate it. He led the first parade in his Rolls-Royce, and Frank Gosden and Charles Correll of Amos ‘n’ Andy fame were the first guests of honor.

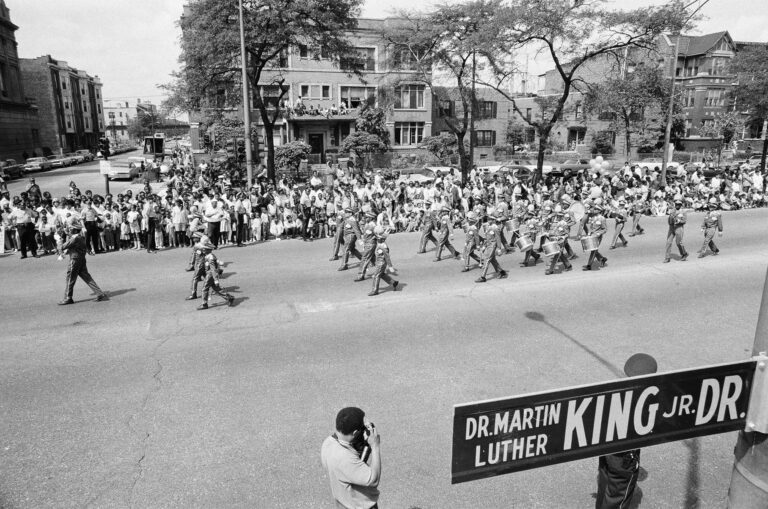

The Bud Billiken Day Parade on Martin Luther King Drive, August 10, 1968. ST-40001296-0004, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; Bob Black, photographer.

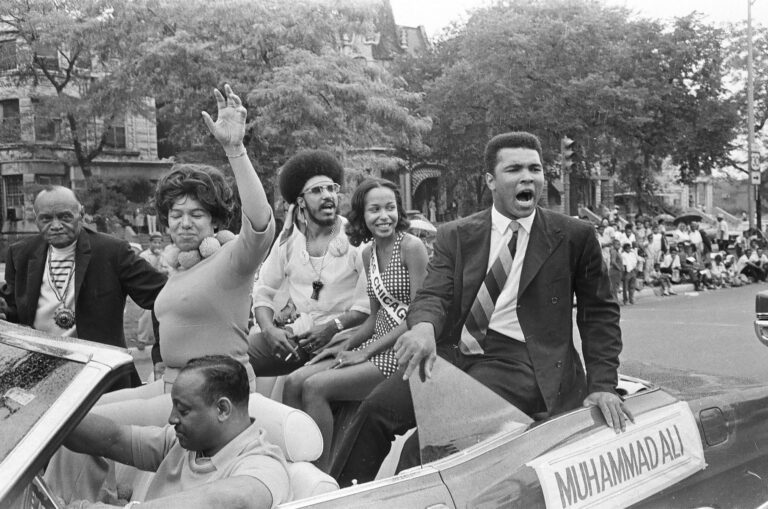

Since the 1940s, the Bud Billiken Day Parade has been sponsored by the Chicago Defender Charities, and has become known as the oldest African American parade in the country. Participants in the parade, which proceeds south on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive from 39th to 51st streets culminating with a picnic in Washington Park, have included presidents Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson; Nat King Cole; Michael Jordan; Muhammad Ali, Oprah Winfrey; and Barack Obama.

Boxer Muhammad Ali rides in a car in the Bud Billiken Day Parade at 39th Street and Martin Luther King Drive, August 9, 1969. ST-40001287-0033, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Toward the late 1990s spectator estimates of the Bud Billiken Day parade, held on the second Saturday of August, ran into the millions, and the event was routinely considered one of the largest of its kind in the United States. See more images of past Bud Billiken Day Parades.

CHM Images

Peruse thousands of digitized prints and photographs at CHM Images, our online portal. Featured galleries include images from our newly acquired Chicago Sun-Times Photography Collection, Raeburn Flerlage’s work documenting the Chicago blues and folk music scene during the 1950s–1970s, and Declan Haun’s photography capturing the American Civil Rights Era. We encourage the use of our images for a variety of personal, nonprofit, and commercial purposes and all proceeds support the Chicago History Museum and our mission to share Chicago stories.

Performers in procession on a street in the Old Town neighborhood, Chicago, c. 1963. CHM, ICHi-132982; Raeburn Flerlage, photographer

The wafting aroma of chicken teriyaki, the rhythmic pulsing of taiko drumming, and the occasional murmur of Japanese on a languid summer day. For sixty-five years, the Ginza Holiday Festival has brought a bit of Japan to Chicago. The tradition.

A performer plays a koto (Japanese zither) at the Ginza Holiday Festival, Chicago, c. 1961. CHM, ICHi-117777; Raeburn Flerlage, photographer

In 1955, the Midwest Buddhist Temple in the Old Town neighborhood sought to create a fundraising event that would introduce Japanese food, culture, and entertainment to the public. With that in mind, the Ginza Holiday Festival was created. The festival’s name comes from the famous district in Tokyo, which for centuries was a destination for shopping and entertainment and still attracts millions of visitors.

Early Ginza Holiday Festivals were brightly lit with Japanese lanterns lining the street outside the temple and featured an authentically decorated stage and traditional red torii gates at the festival’s entrances. It was at the inaugural festival that its now-famous chicken teriyaki was introduced, a family recipe of an early temple member. Entertainment consisted of classical Japanese dancing, minyo (Japanese folk dancing), musicians such as shamisen and koto artists, and martial arts demonstrations, including judo, karate, and kendo.

In the 1970s, the Ginza Holiday Festival further enhanced its offerings by adding performances of taiko (Japanese drumming) and beginning a relationship with the Waza, an organization of more than 100 Japanese artisans who each master a craft that has been handed down through their families for 300 years since Japan’s Edo period.

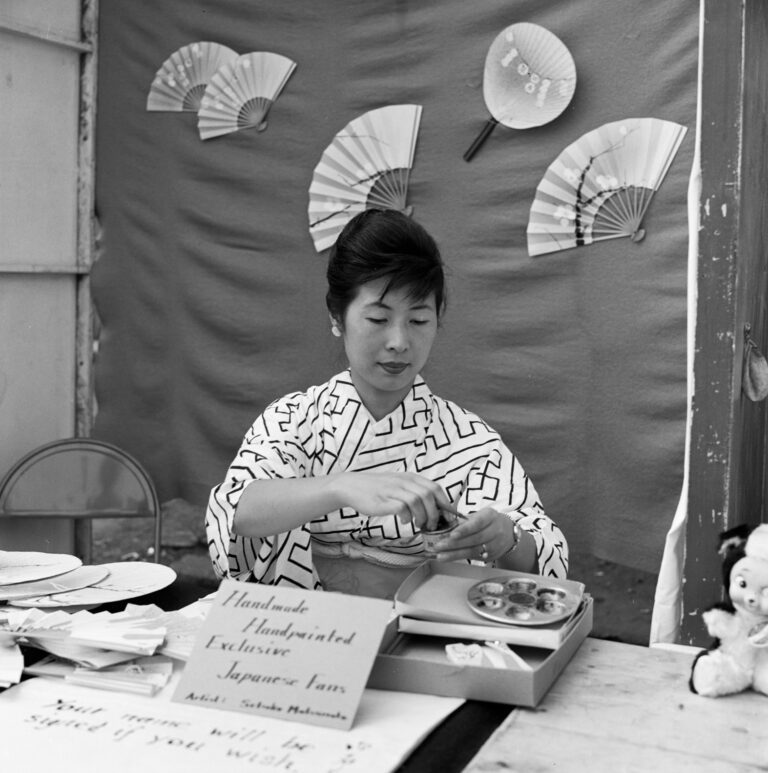

A vendor selling hand-painted fans at the Ginza Holiday Festival, Chicago, c. 1963. CHM, ICHi-133016; Raeburn Flerlage, photographer

Each year, various Waza craftsmen travel internationally to share their artistry, and in August a small group of artisans visit the Ginza Holiday Festival, bringing unique art such as hand-thrown pottery, delicately detailed Japanese dolls, and silkscreened cloth towels. In addition to food, entertainment, and arts and crafts vendors, the Midwest Buddhist Temple’s resident minister opens the hondo (temple hall or chapel) and invites visitors to tour the temple and learn about Jodo Shinshu Buddhism.

A performer with a child during the Ginza Holiday Festival, Chicago, 1960. CHM, ICHi-132972; Raeburn Flerlage, photographer

For many Chicagoans, the Ginza Holiday Festival provides an opportunity to experience a different culture, connect with new acquaintances, and reconnect with old friends. See more images.

CHM Images

Peruse thousands of digitized prints and photographs at CHM Images, our online portal. Featured galleries include images from our newly acquired Chicago Sun-Times Photography Collection, Raeburn Flerlage’s work documenting the Chicago blues and folk music scene during the 1950s–1970s, and Declan Haun’s photography capturing the American Civil Rights Era. We encourage the use of our images for a variety of personal, nonprofit, and commercial purposes and all proceeds support the Chicago History Museum and our mission to share Chicago’s stories. See more images.

In this post, we commemorate the birthday of Dr. Nathan Wright Jr. A prolific writer of eighteen books, Wright was an internationally renowned scholar whose research focused on the rise of the Black Power movement in the 1960s and 1970s. As an activist, he was seen as a moderating and conciliatory voice that advocated for Black Power as part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Wright suggested more aggressive tactics in the struggle for equality, alienating many leaders in the mainstream Civil Rights Movement.

In this post, we commemorate the birthday of Dr. Nathan Wright Jr. A prolific writer of eighteen books, Wright was an internationally renowned scholar whose research focused on the rise of the Black Power movement in the 1960s and 1970s. As an activist, he was seen as a moderating and conciliatory voice that advocated for Black Power as part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Wright suggested more aggressive tactics in the struggle for equality, alienating many leaders in the mainstream Civil Rights Movement.

Wright served as the chairman of the first National Conference on Black Power in 1967, which was attended by more than 1,000 delegates representing 286 organizations. The New York Times noted that the event represented a major shift in Black intellectual life and quoted Wright as saying that his notion of Black Power depended “on the capacity of black people to be and to become themselves, not only for their own good, but for the enrichment of the lives of all.”

In 1969, he was the founding chair of the Department of African and Afro-American Studies at the State University of New York at Albany. As an ordained Episcopal minister, Wright served as the executive director of the Department of Social Work in the Episcopal Diocese of Newark, New Jersey, and later in his life, he preached his lifelong message of self-reliance along the Eastern Seaboard. In 2005, Wright died at the age of eighty-one from kidney disease.

In the aftermath of the urban insurrections in Detroit and Newark in 1967, Studs Terkel interviewed Nathan Wright about his book Black Power and Urban Unrest. Acknowledging that the term “Black Power” had become widely associated with violence, Terkel was especially intrigued by Wright’s subtitle: Creative Possibilities. The conversation that ensued identified power as an expression of the creative potentiality of life itself, and in this respect the interview underscores how much the Black Power movement could be understood to represent a veritable creative renewal of culture and political life in the United States. Listen to the interview.

A Black man holds up a sign that reads “Black Power” at the Cicero March in Cicero, Illinois, 1966. CHM, ICHi-036894; Declan Haun, photographer

Studs Terkel Radio Archive

In his forty-five years on WFMT radio, Studs Terkel talked to the twentieth century’s most interesting people. Browse our growing archive of more than 1,200 programs. Explore the archive.