Latest Posts

Watch fob with amethyst stone by Carence Crafters, c. 1910. Clockwise from top: ICHi-074261, ICHi-074260, ICHi-074263. All images by CHM staff.

Amethyst is the birthstone for February. The word “amethyst” is derived from “amethystos” in Greek, with the prefix a-, meaning “not,” and methyein “to be drunk with wine,” because the ancient Greeks believed that the stone could prevent or cure drunkenness in its wearer.

This watch fob (c. 1910) was made by Carence Crafters, a Chicago-based design firm that specialized in Arts and Crafts–style products. It has a pyramid-cut amethyst in a silver Celtic knot–style setting, a motif that appeared frequently in their work. On the back is the word “STERLING” and the Carence Crafters mark of two interlocking Cs in a square. Prior to World War I and the development of the wristwatch, most watches designed for men had to be carried in a pocket. The wearer would have attached his watch to the latch and let the amethyst hang out of his pocket.

Carence Crafters was incorporated on March 7, 1908, with three investors: R. D. Camp, Carl D. Greene, and John H. Dunham. Their output was largely copper and brass jewelry, as well as household items such as candleholders, trays, desk sets, boxes, and picture frames, which were distributed to a nationwide network of retail shops and department stores. As very few of Carence Crafters’ business records exist today, it is unknown why the company filed paperwork to cancel their charter in March 1911.

Explore our costume collection to see more accessories.

The Chicago History Museum today announced the acquisition of 117 photographs and two copies of Chicago Protests: A Joyful Revolution, from Chicago-based visual artist and author, Vashon Jordan Jr. His donated work was inspired by civil injustices in 2020 and the persistent demonstrations that took place across Chicago, showcasing the resilience and authenticity of Chicago and its people. Chicago Protests: A Joyful Revolution is currently in the museum’s research center and the photographs will be made available to the public on the Museum’s image portal later this year. Several photos will be featured in an upcoming exhibition that highlights the tumultuous and triumphant events of 2020.

“Vashon Jordan Jr.’s work sheds light on our city’s strength and resilience and aligns directly with our mission to share Chicago stories,” said Charles E. Bethea, Andrew W. Mellon Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs at the Chicago History Museum. “We are honored to have his poignant work in our collection and make his photographs available to the public to learn from and shape our future.”

Jordan Jr.’s book, Chicago Protests: A Joyful Revolution, showcases his photos from more than 35 different demonstrations and moments in Chicago that shaped a summer of unrest in 2020. His partnership with the museum is ongoing and includes additional photo donations featuring Lori Lightfoot’s inauguration in 2019 and future notable events in Chicago.

“The city of Chicago showed unmatched resilience and hope during the summer of 2020, sparked by unrest and civil injustices taking place across the country. When we look back on this time, I want young people to see themselves represented for the enormous strides we made together,” said Vashon Jordan Jr., author of Chicago Protests: A Joyful Revolution. “I am excited to share my photography with the Chicago History Museum and its audiences, as it shows people of all backgrounds and identities coming together in solidarity, embarking on a joyful revolution.”

Vashon Jordan Jr., 21 years old, is a visual artist who uses photography and videography to showcase authentic moments that reflect the people of Chicago. He enjoys engaging with youth across the city to inspire and encourage activism. Jordan Jr. received his Associate in Arts from Kennedy-King College and is currently studying at Columbia College Chicago

Following a diligent search process and subsequent vote by the board of trustees, the Chicago History Museum today announced that Donald E. Lassere, President of the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville, KY will succeed Gary T. Johnson as Museum president. Johnson is retiring after more than 15 years as president at CHM.

The presidential search committee was led by Daniel S. Jaffee, CHM’s board chair. The committee included ten board members and was assisted by an external consulting firm. The search took many months and culminated in finalists’ participation in virtual town hall meetings with museum staff and a safe, in-person museum visit.

“Conducting our search during the COVID-19 pandemic certainly posed some challenges, as initial vetting and interviews were done virtually,” said Jaffee. “I am grateful for the time and passion each committee member dedicated to the process, and proud of the decision we made. Thanks to the incredible job that Gary Johnson and his team have done over the years, the museum was in the enviable position of being a very attractive landing spot for highly qualified candidates, and we are excited to welcome Donald Lassere to his new role.”

Born in Chicago, Lassere and his family moved several times during his youth before returning to the city, where he graduated from Percy Julian High School. Motivated by his love for history and experiences in nonprofits, cultural spaces and the private sector, Lassere plans to leverage his diverse background by honing CHM’s audiences and providing valuable experiences for all visitors.

“Chicago holds such importance in my life, and I am thrilled to return to my hometown to work with the dynamic team at the Chicago History Museum and lead with the mission to share Chicago stories at top of mind,” said Lassere. “I believe we have an incredible opportunity to be truth tellers at CHM, sharing both the beautiful and unpleasant sides of our history that have shaped Chicago as we know it. CHM’s collection holds countless stories that have yet to be told, and I am honored to lead the institution in providing our visitors an inspiring, fun and educational experience.”

Lassere joins CHM with notable experience across industries. He has been President and CEO of the Muhammad Ali Center and Museum (MAC) since 2012, providing leadership that enhanced the reputation of the center on a local, national and global basis. Before his work at MAC, Lassere served in numerous roles, including Senior Vice President for Scholarship America, where he led Scholarship Management Services, the nation’s largest administrator of education assistance programs. In addition, he implemented grassroots programs to serve students in almost 4,000 communities and provide financial aid opportunities. He is an adjunct professor of organizational behavior and leadership at University of Louisville’s MBA and Entrepreneurial MBA programs.

Lassere is active in several community organizations and committees. He is Board Chair of the Louisville Visitor and Convention Bureau, served as a member of the selection committee for the Grawemeyer Award in Education, and was a board member of the Louisville Downtown Development Corporation, among other organizations.

“I welcome Donald Lassere back to Chicago and am very excited about the new perspectives he will bring,” said Johnson. “I am grateful to the people of Chicago for the privilege of leading Chicago’s own museum for almost 16 years. With Donald Lassere as president, the best is yet to come.”

Gary Johnson will remain president of CHM while Lassere and his family relocate to Chicago. Lassere will begin at CHM on April 12.

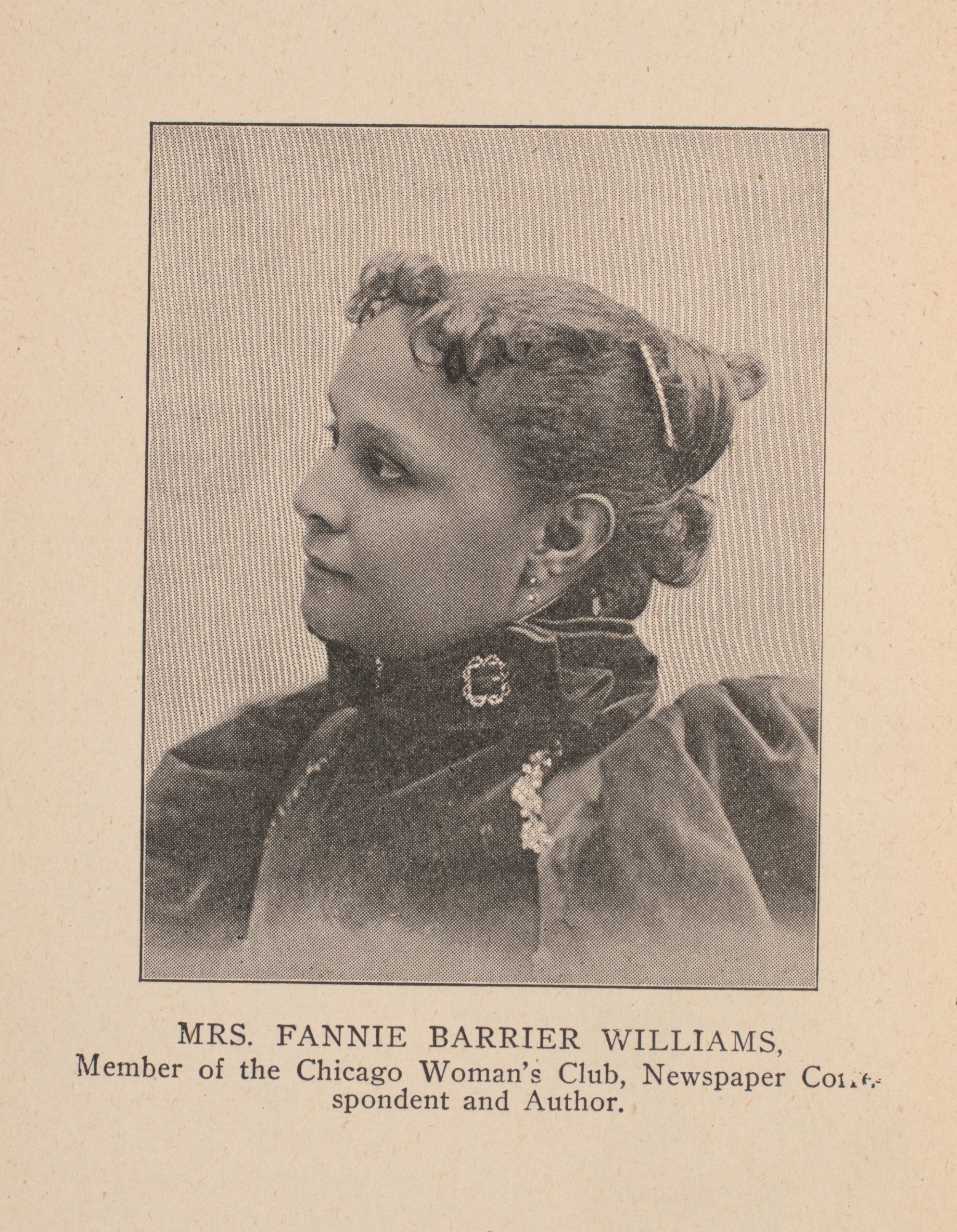

On February 12, 1855, Fannie Barrier was born in Brockport, New York. She was the first African American to graduate from Brockport State Normal School (now SUNY-College at Brockport) in 1870. She held several teaching positions, first in Missouri and later in Washington, DC, where she met her future husband, S. (Samuel) Laing Williams, a law student. The couple married in 1887 and settled in Chicago, where they were active among community reformers.

Though often not treated as an equal in organizations run by white women, Barrier Williams joined the Illinois Woman’s Alliance (IWA), which worked to obtain legislative support for women’s issues, particularly regarding health. However, Black women faced the dual burden of racism and sexism and did not have the luxury of battling only for women’s rights. Their longtime activism reached new heights in the early 1890s with the creation of a network of women’s clubs devoted to social action. Many of the issues they addressed remain painfully familiar and unresolved, such as a racist criminal justice system, violent attacks on Black people intended to maintain racial oppression, exclusion from white institutions, and economic disparities.

Chicago women were leaders in this national movement. Barrier Williams helped found the National League of Colored Women in 1893, created the National Federation of Afro-American Women with Mary Church Terrell in 1895, and represented Illinois’s Black clubwomen at the Colored Woman’s Congress in Atlanta in 1895. To her, the women’s club movement was a “national uprising” of Black women “pledged to the serious work” of racial advancement.

Learn more about the Black women’s club movement in the “Visionary Women” part of our online experience Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.

About Democracy Limited

A century after ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, the Chicago History Museum invites visitors to explore women’s activism in Chicago to secure the right to vote—and beyond. In our digital experience, Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote, discover the ways women organized to challenge the status quo and how these different paths led to a mass movement for suffrage. Find out what the vote did and did not accomplish, and for whom. Connect themes of the past with the present, which remind us that while injustice and inequality persist, so do activist women.

Fred Harvey lunchroom and restaurant at Union Station, Chicago, June 29, 1943. HB-07469-B, CHM, Hedrich-Blessing Collection.

When traveling by train was common practice, stopping at a Fred Harvey-owned establishment was almost a guarantee.

In 1876, a young English immigrant named Fred Harvey opened a small restaurant at a train depot in Topeka, Kansas. It was the start of what became an empire of hotels, shops, and eating establishments extending from the Great Lakes to the Pacific coast. By the 1880s, Harvey was operating seventeen restaurants along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway’s main line to which he added fifteen Harvey House restaurants by 1891. Harvey’s success was the result of his belief in giving delicious food with excellent service with linen and silverware at reasonable prices.

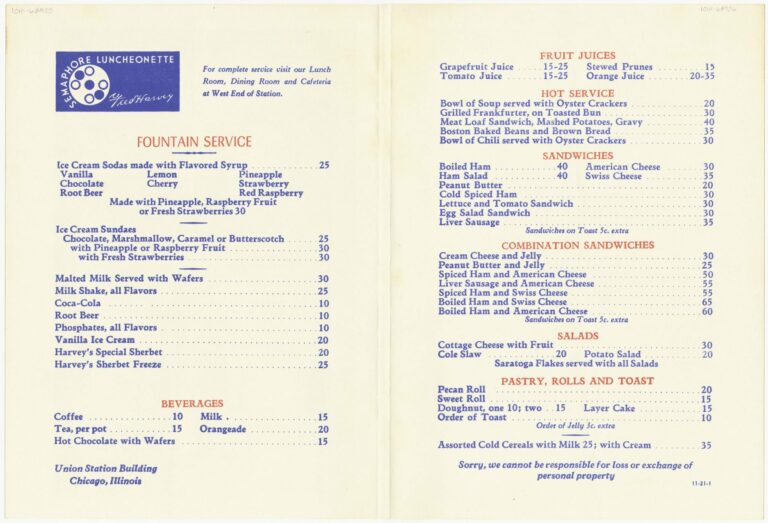

In Chicago, Harvey Co. establishments operated at both the Dearborn Station and Union Station. The company had eateries in Union Station from the beginning when the building opened in 1925, including the lunchroom and club-like dining room (top image), the cafeteria, Shoppers Mart soda fountain, and Iron Horse cocktail lounge. The menu shown above is for the Semaphore Luncheonette in 1941. All the items could be prepared or served quickly, making them ideal for travelers on a tight schedule. The Harvey Co. expanded into non-railroad restaurants, and Chicago had the Kungsholm Restaurant, Harvey House Restaurant, and Harlequin Restaurant, among others.

Fred Harvey died in 1901, and his sons operated the company through the 1930s. As air and car travel increased, business at railroad-based eateries declined. World War II provided a temporary boost with the Harvey Co. making meals for troop trains, but by the 1950s, railroad companies were consolidating service and closing depots. The Harvey Co. shifted its food service and hotel business to US national parks and was purchased by Amfac Corp. in 1968. In 2019, Amtrak announced plans to renovate the former Fred Harvey restaurant at Union Station and transform it into a dining and retail complex.

Inside front cover of 75th Anniversary Semaphore Luncheonette restaurant menu, Chicago, 1941. CHM, ICHi-068925, ICHi-068926.

Trace the city’s evolution from meatpacking capital to foodie paradise through our Google Arts & Culture exhibit Touring Chicago’s Culinary History, which features menus from the CHM Research Center.

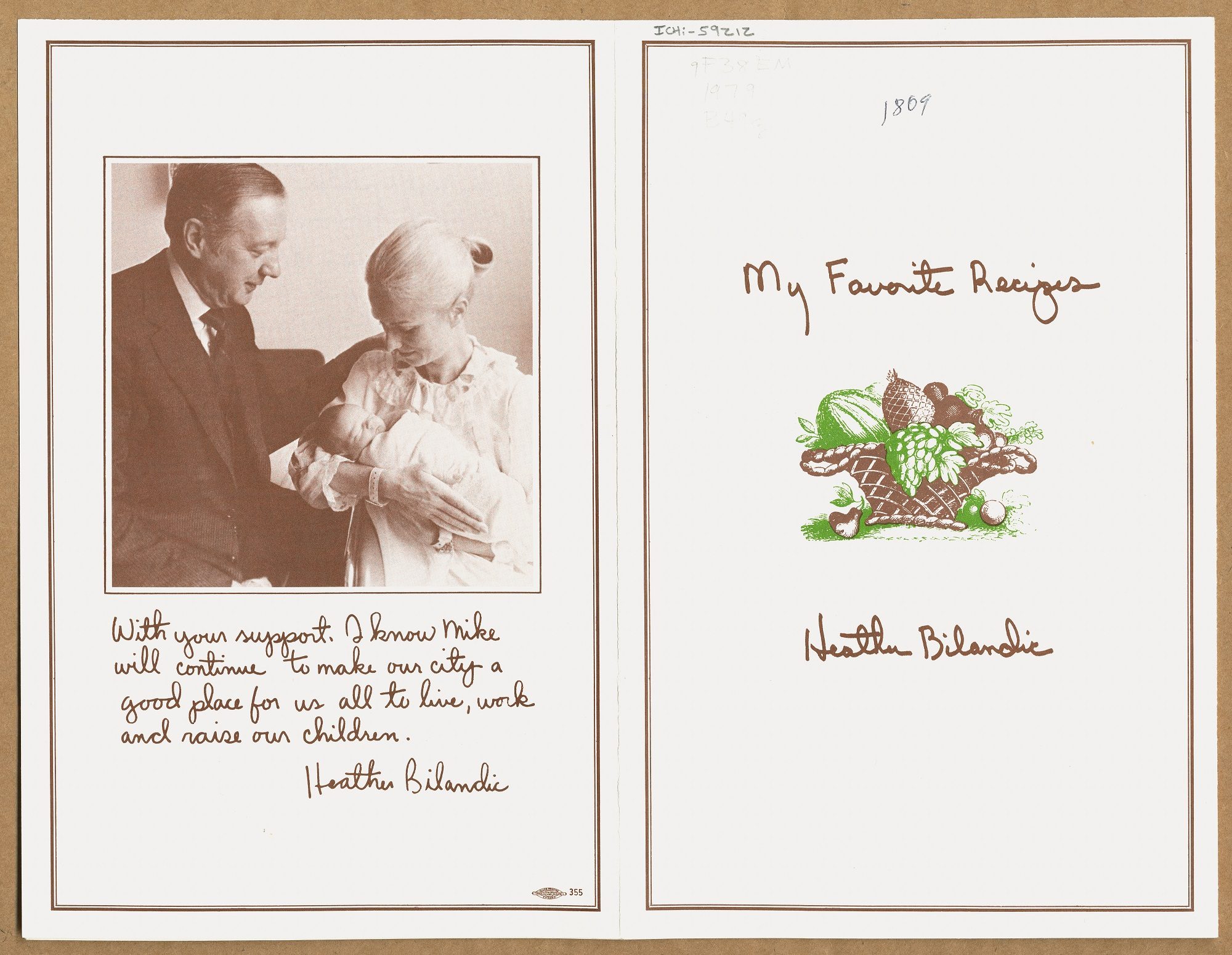

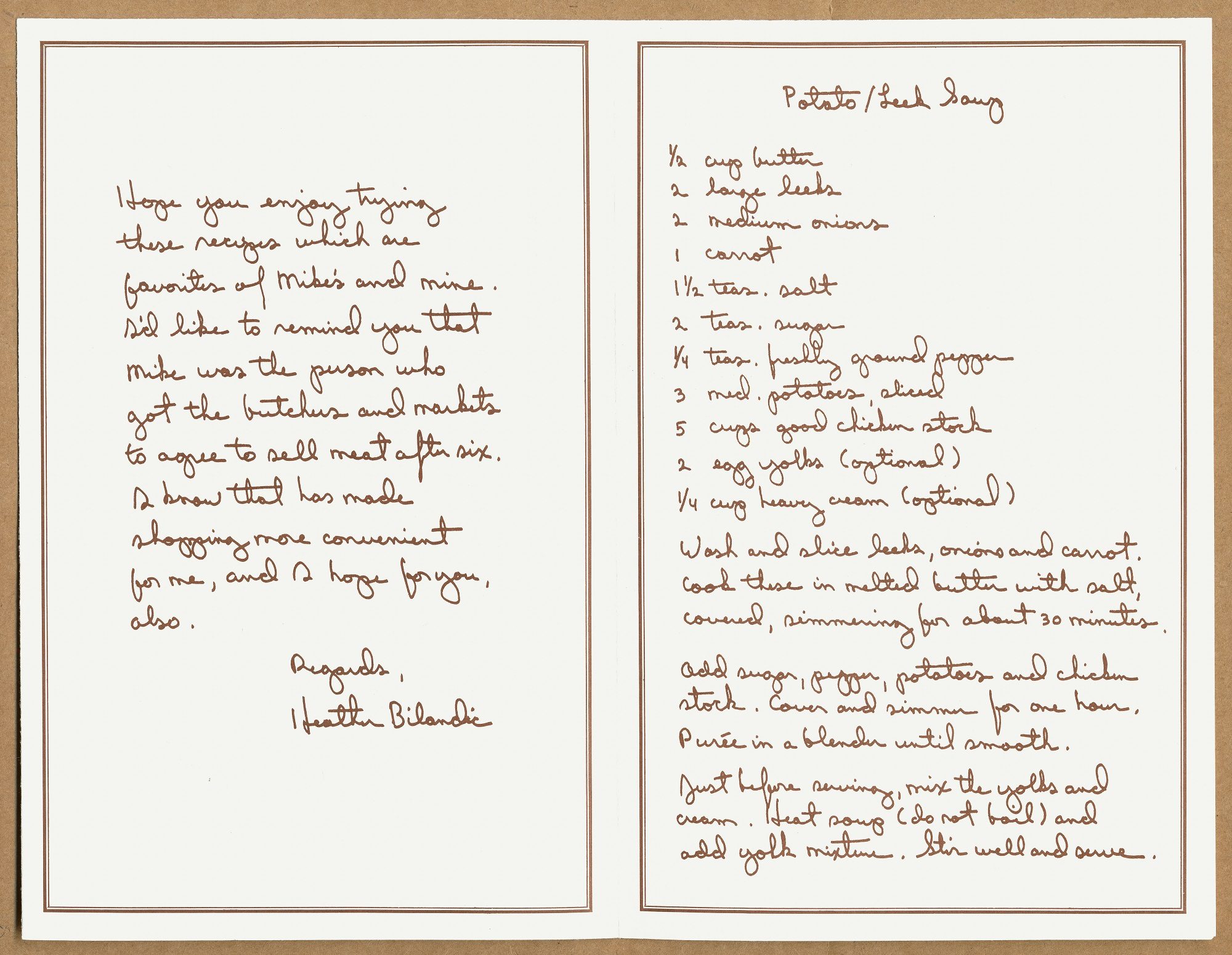

Michael A. Bilandic became mayor after the death of Richard J. Daley in 1976. During his 1979 election campaign, Bilandic emphasized his ethnic and family loyalties with this brochure that included various recipes from his wife, Heather Bilandic, including such as her Potato/Leek Soup. Bilandic was soundly defeated by Jane Byrne during the Democratic primary.

Michael A. Bilandic campaign literature and recipe booklet, 1979. CHM, ICHi-059212

Message on left:

With your support, I know Mike

will continue to make our city a

good place for us all to live, work

and raise our children.

Heather Bilandic

Message on left:

Hope you enjoy trying

these recipes which are

favorites of Mike’s and mine.

I’d like to remind you that

Mike was the person who

got the butchers and markets

to agree to sell meat after six.

I know that has made

shopping more convenient

for me, and I hope for you,

also.

Regards,

Heather Bilandic

Recipe on right:

Potato/Leek Soup

½ cup butter

2 large leeks

2 medium onions

1 carrot

1½ teas. salt

2 teas. sugar

¼ teas. freshly ground pepper

3 med. potatoes, sliced

5 cups good chicken stock

2 egg yolks (optional)

¼ cup heavy cream (optional)

Wash and slice leeks, onions and carrot. Cook these in melted butter with salt, covered, simmering for about 30 minutes.

Add sugar, pepper, potatoes and chicken stock. Cover and simmer for one hour. Purée in a blender until smooth.

Just before serving, mix the yolks and cream. Heat soup (do not boil) and add yolk mixture. Stir well and serve.

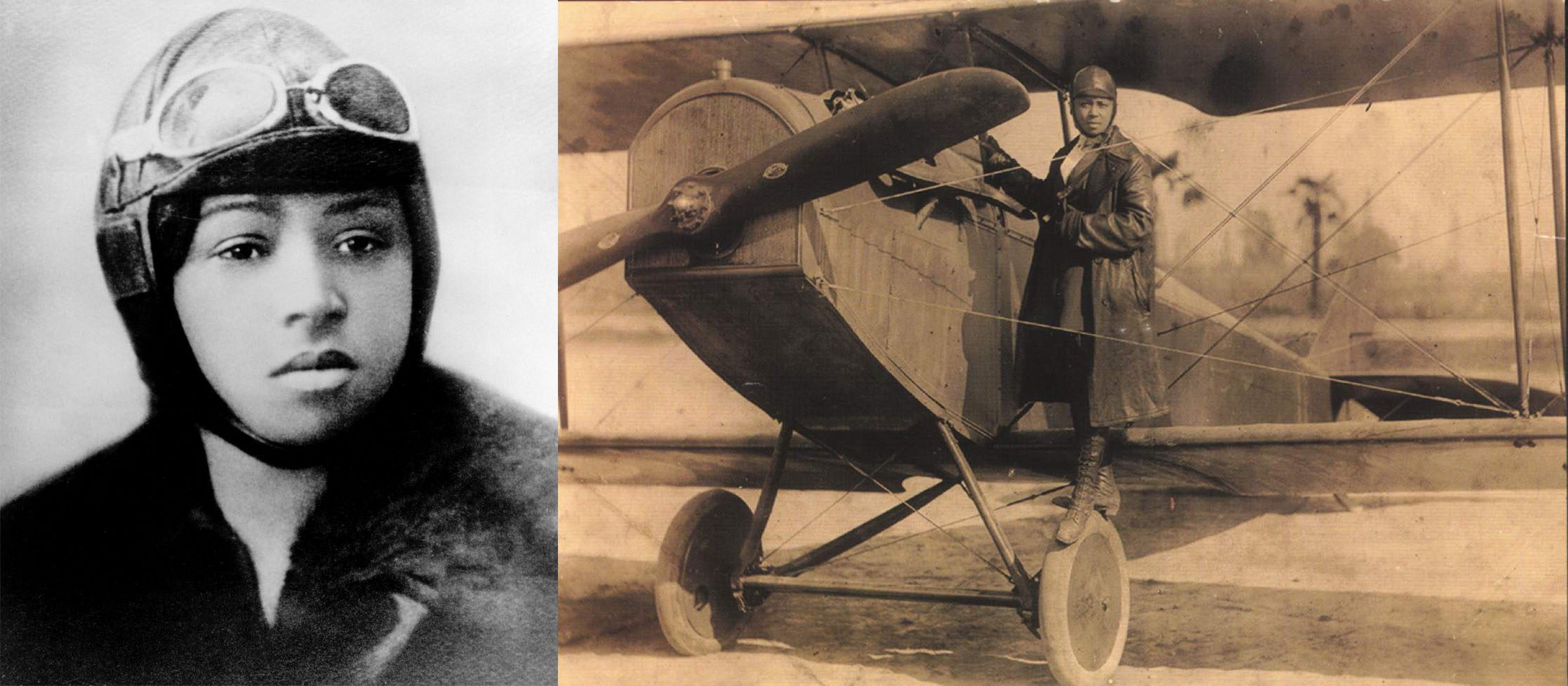

From left: Portrait of Bessie Coleman, pilot, c. 1921. CHM, ICHi-026774. Bessie Coleman on the wheel of a Curtiss JN-4 “Jennie” in her custom-designed flying suit, c. 1924. NASM 92-13721, Smithsonian Institution.

On January 26, 1892, Bessie Coleman was born in Atlanta, Texas. She was the first Black woman in the world to earn an aviator’s license.

A daughter of George and Susan Coleman, Bessie Coleman was one of thirteen children. During her youth, a number of aviation milestones may have influenced her: in 1903, the Wright brothers made the first controlled, sustained flight of a powered heavier-than-air aircraft; in 1910, Baroness Raymonde de la Roche became the first woman to earn a pilot’s license; in 1911, Harriet Quimby became the first American woman to earn a pilot’s license; and in 1917, Eugene Jacques Bullard became the first African American military pilot to fly in combat, and the only African American pilot in World War I, albeit for France.

Like many other African Americans in the early twentieth century, Coleman decided to seek better opportunities in the North. She moved to Chicago in 1915 and lived with two of her brothers on the South Side. Both of them had fought overseas during World War I and most likely encouraged her dream of becoming a pilot. However, she faced prejudice both as a woman and an African American and found herself unable to train in the United States.

With the encouragement of Robert S. Abbott, publisher of the Chicago Defender, Coleman learned French and saved up money from her work, first as a manicurist and then a manager of a chili parlor. In November 1920, she gained entrance into the Caudron School of Aviation in Le Crotoy, France. On June 15, 1921, Coleman obtained her pilot’s license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, and after some additional training in Paris, she returned to the United States in September 1921.

Upon her return, Coleman became a barnstormer with the Chicago Defender as her sponsor and toured the United States. On October 15, 1922, more than 2,000 people came to the Checkerboard Field in west suburban Maywood (now Miller Meadow Forest Preserve) for her first exhibition in Chicago. Coleman died in a plane crash in Florida in 1926.

Inspired by Bessie Coleman, a group of African American pilots organized the Challenger Air Pilots Association in 1931. The organization founded an airport in south suburban Robbins in 1933 to accommodate the needs of African American pilots who faced discrimination at other Chicago airports.

Learn more about Chicago’s airports in our Encyclopedia of Chicago entry.

Studs Terkel Radio Archive

Studs Terkel talked to the twentieth century’s most fascinating people in his forty-five years on WFMT radio, from notable experts and award-winning performers to ordinary folks and everyday citizens. In 1981, he spoke with air traffic controller Jim Paulei about what a day on the job looks like and the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) strike.

On this day in 1942, Muhammad Ali (né Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.) was born in Louisville, Kentucky. He began boxing at twelve years old and rose quickly to national prominence, becoming an amateur boxing champion by the time he graduated high school. Ali gained valuable experience in the late 1950s—in 1958, he competed in the Golden Gloves tournament at Chicago Stadium and narrowly missed attending the 1959 Pan Am Games in Chicago, losing in the trials to Amos Johnson, who eventually won gold there. By the next summer, Ali qualified for the 1960 Olympics in Rome, where he won the light heavyweight gold medal, catapulting him to international fame and the start of his professional career.

In 1962, Muhammad Ali attended a Nation of Islam Saviours’ Day event where the opening speaker was Malcolm X, a charismatic Nation of Islam (NOI) minister who spent the previous decade attracting new converts and establishing new temples around the US. The NOI was founded in Detroit in 1930 and moved to Chicago in the mid-1930s, where its headquarters has remained since. By 1964, Ali became a member of the NOI, shed his birth name of Cassius Clay Jr., and moved to Chicago’s South Side, where he lived for about twelve years to further his studies.

While living in Chicago, Ali continued his boxing training. He used this jump rope, which he gifted to Sultan Muhammad, the son of his personal manager, Jabir-Herbert Muhammad. Sultan Muhammad served as the personal pilot and aide to NOI leader Elijah Muhammad, his grandfather. In 1985, Jabir-Herbert Muhammad received this limited-edition, gold-plated World Boxing Council belt buckle to mark Muhammad Ali’s reign as the greatest boxer of all time. The back bears Ali’s facsimile signature and the edition number 5,358. Both of these objects were loaned to the Chicago History Museum for our exhibition American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago.

Listen to Muhammad Ali discuss his childhood and family, conversion to Islam, stance on the Vietnam War, and experiences in jail in his oral history interview with Studs Terkel.

From left: Muhammad Ali (hand on chin) wears a Fruit of Islam uniform as he listens to the leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, speak to a crowd at the Saviours’ Day event in the Coliseum at 15th St. and Wabash Ave., Chicago, February 27, 1966. ST-19031786-0007, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM. Jump rope with autographed handle, United States, c. 1970. Commemorative World Boxing Council belt buckle, 1985. Both items courtesy of Sultan Rahman Muhammad. Muhammad Ali training in Chicago, published on page 9 of Muhammad Speaks, November 10, 1967. CHM, ICHi-177193A.

Studs Terkel Radio Archive

In his forty-five years on WFMT radio, Studs Terkel talked to the twentieth century’s most fascinating people. Browse our growing archive of more than 1,200 programs. Explore the archive.

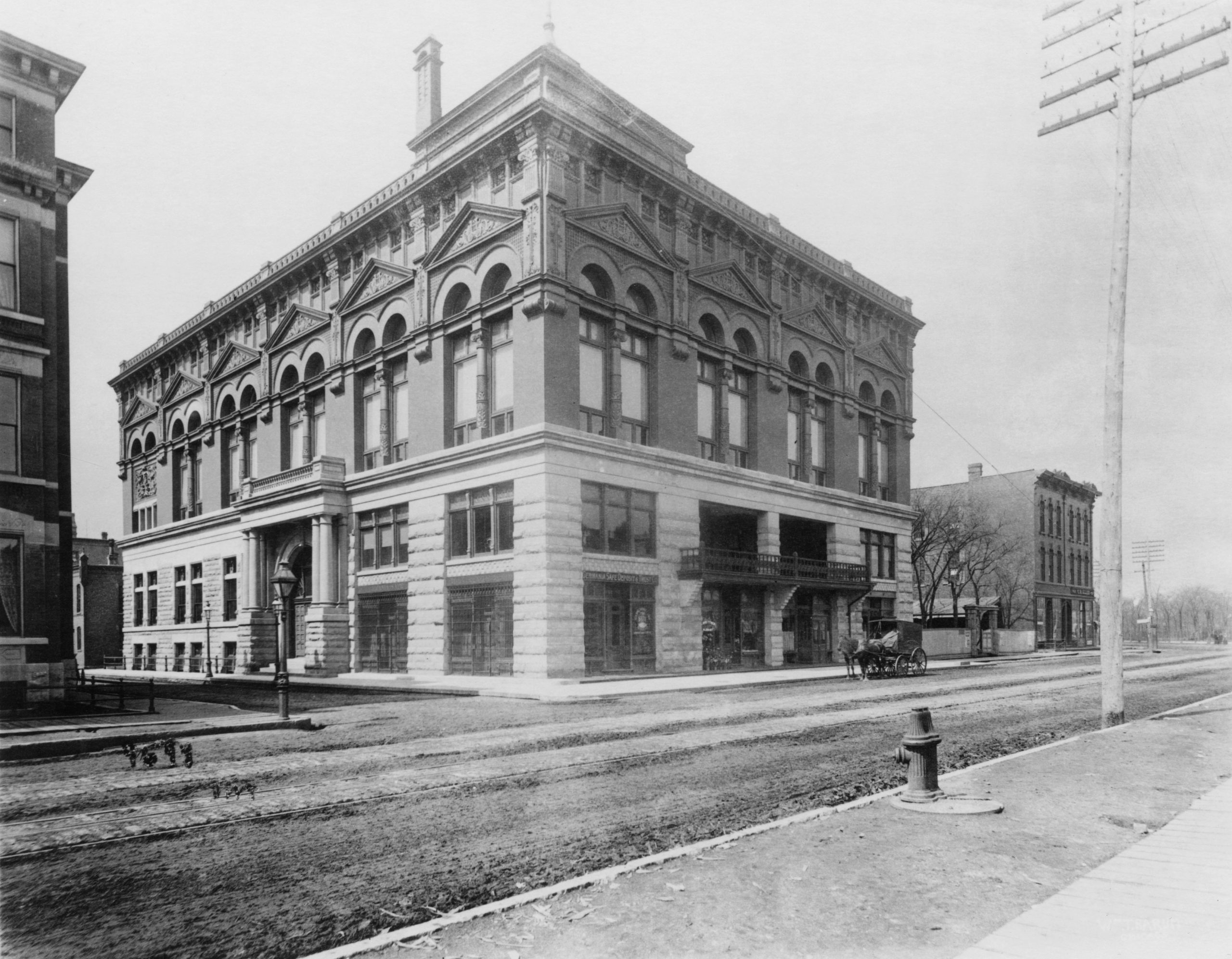

An undated photograph of the Germania Club at Clark Street and Germania Place, Chicago. CHM, ICHi-015118; W. T. Barnum, photographer

On January 13, 2011, the Germania Club Building in the city’s Old Town neighborhood was designated a Chicago Landmark. The history of this neighborhood club can be traced back to the Germania Männerchor, a men’s chorus comprising German American Civil War veterans who sang at President Abraham Lincoln’s funeral ceremonies in Chicago in 1865.

Chicago’s first substantial German community took shape in the 1850s when immigrants from Bavaria and Württemberg settled around what is now the Near North Side. Traces of that early group can still be found in that area, such as the Glunz Tavern (1888) and St. Michael’s parish, which was established in 1852 to serve a German Catholic congregation. Choirs thrived within the German immigrant community, as they were a vital social network and helped preserve ethnic identity. The Männergesangverein (1852) was among Chicago’s earliest ethnic choral societies, followed by the Germania Männerchor (1865) and the Concordia, an offshoot that split from Germania in 1866.

The Germania Männerchor became known as the Germania Club shortly after its founding and had the distinction of being the city’s oldest German American organization. When their building was completed in 1889, it served as a focal point for Chicago’s German American community through much of the twentieth century. It was designed by W. August Fiedler, a German immigrant and club member who was a partner at the architectural firm Addison & Fiedler. With its round-arched window openings and thick-masonry walls, the Germania Club Building’s design combines stylistic features of the Romanesque Revival style, as well as the neoclassical style, as seen in its pedimented windows, projecting cornice, and columned entrance portico. Inside, the building features grand historic spaces, including a ballroom with thirty-five-foot-tall walls and a large dining room. The Germania Club Building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

The club was briefly called the Lincoln Club during World War I when anti-German sentiment was strong in the United States, but reverted to its original name in 1921. Amidst an evolving neighborhood and increased options for socializing, the Germania Club dwindled in numbers until it was disbanded in 1986. The Germania Club records, which are now housed in CHM’s Abakanowicz Research Center, includes sheet music and account ledgers.

Learn more about the history of Chicago’s German community in our Encyclopedia of Chicago entry.

The Knights of Pythias Temple at 3737 S. State St., Chicago, 1928. CHM, ICHi-019351. A terra-cotta tile depicting a griffin from the Knight of Pythias Temple in Chicago, 1927. CHM, ICHi-066658.

On this day in 1882, Walter T. Bailey was born in Kewanee, Illinois, to Emanuel and Lucy Bailey. He was the first African American to graduate with a BS in architectural engineering from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the first licensed African American architect in the state of Illinois, and the first licensed African American architect in Chicago.

Upon his graduation from the University of Illinois in 1904, Bailey worked in firms in Kewanee and Champaign. In 1905, he was appointed head of the Mechanical Industries Department at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, where he also supervised planning, design, and construction of several campus buildings. Bailey left Tuskegee in 1916 to open his own office in Memphis, where he made business contacts with the Knights of Pythias, a fraternal organization that was integrated at its founding in 1864, became segregated beginning in 1880, and didn’t reintegrate until 1990 because both Black and white branches were secret societies and each branch had lost track of the other. Bailey soon received the biggest commission of his career—the Knights of Pythias’ new national headquarters in Chicago—and planning began in 1922. By 1924, he moved his practice to Chicago to supervise the project.

From the start, the National Pythian Temple was designed to impress. The eight-story Egyptian Revival building featured terra-cotta planters and detailing on its exterior, as well as a 1,500-seat theater and rooftop garden, all in the heart of the bustling Bronzeville neighborhood at State and 37th Streets. Completed in 1928, it was deemed the world’s largest, most expensive building ever built and designed by Black people. The Knights of Pythias eventually lost ownership of the building, and it was reconfigured into multiunit housing as part of a project with the Works Progress Administration, the federal employment program that President Franklin Roosevelt established in 1935. The building was abandoned by the 1970s and demolished in 1980. It is still considered one of the major African American architectural projects of the early twentieth century.

Despite this large commission early in his career, Bailey was not able to sustain his success—his subsequent work consisted of smaller projects such as churches and renovations. When the Great Depression began, Chicago’s Black business community saw widespread financial ruin, further reducing the possibility of new construction. Bailey’s final large project was the First Church of Deliverance (1939), and at the time of his death on February 21, 1941, he was working on the interior remodeling of Olivet Baptist Church.

See more images from our collection of architectural photography.

CHM Images

Peruse a selection of digitized prints and photographs at CHM Images, our online portal. Featured galleries include images from our recently acquired Chicago Sun-Times Photography Collection, Raeburn Flerlage’s work documenting the Chicago blues and folk music scene during the 1950s–1970s, and Declan Haun’s photography capturing the American Civil Rights Era.