Latest Posts

In this blog post, learn about how a painted mantelpiece was prepared before it went on display in our exhibition American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago, from cleaning and repair in the conservation lab to being installed in the gallery.

Any object that is considered for display in an exhibition, whether from the Chicago History Museum’s collection or a special loan, is brought to the conservation lab to be assessed for its current condition and any treatment needs, and to establish the best parameters for its display. This assessment is an important and necessary step in the exhibition process as it ensures that each object is stable enough to withstand the rigors of display and are not damaged or harmed as a result.

CHM conservator Holly Lundberg carefully cleans the mantelpiece. All photographs by CHM staff.

Most objects require some level of preparation and conservation treatment such as cleaning, stabilization, and/or repair, and the creation of a custom mount before they can be displayed in a safe and appropriate way. Upon examination of this painted wood mantelpiece, which MarQ Shaheer loaned to the Museum for our exhibition American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago, CHM conservator Holly Lundberg noted that the paint and ground layers were cracked, lifting, and actively flaking from the wood substrate, and significant losses had occurred in spots overall. The piece was also covered with a layer of surface dust, dirt, and grime.

A closeup view of paint that has lifted from the wood substrate of the mantelpiece.

To stabilize areas of loose and actively flaking paint, Lundberg used a syringe to inject a conservation grade adhesive between cracked, loose, and lifting areas of paint and ground and the wood substrate to consolidate them. And, where necessary, she used a small heat-spatula and a barrier layer of double-sided silicone release film to soften and lay down lifting paint fragments. Consolidation of the unstable paint and ground layers took several weeks to complete, and in some spots more than one application of the consolidant was required.

A closeup view of Lundberg using a soft-bristle brush to sweep dust toward a low-suction vacuum.

Once the surface layers were stabilized, Lundberg was able to use soft, natural-bristle artists brushes and a low-suction vacuum to remove any loosely adherent dust and dirt from the surface, and lightly moistened cotton swabs to remove dirt and grime.

At right, the mantelpiece on display in American Medina: Stories of Muslim Chicago, courtesy of MarQ Shaheer.

The decoratively painted wood mantelpiece ornamented the Nation of Islam (NOI) mosque in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood in the early 1970s. Under Elijah Muhammad’s leadership, the NOI bought the former Saints Constantine and Helen Greek Orthodox Church. After his father died, W. D. Mohammed renamed it the Elijah Muhammad Mosque, No. 2. Eventually, it became Mosque Maryam, named for Jesus Christ’s mother, who is the only woman named in the Quran. The Arabic words, reading from right to left, are the shahādah, the Muslim profession of faith: “There is no God but God, and Muhammad is his messenger.”

Alonzo Chappel, “The Last Hours of Abraham Lincoln,” oil on canvas, 1868. CHM, ICHi-052425

On April 15, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln died in the Petersen family’s boarding house in Washington, DC, at 7:22 a.m. The night before, John Wilkes Booth shot him during a performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre, and soldiers carried Lincoln across Tenth Street so that he could pass his last moments peacefully and not risk a bumpy carriage ride back to the White House.

The bedroom at the Petersen House just after Lincoln’s remains were carried out, Washington, DC, April 15, 1865. CHM, ICHi-011209; Julius Ulke, photographer

After Lincoln’s body was removed, the bed on which Lincoln died followed a circuitous route to Chicago. The owner of the Petersen House, William Petersen, died in 1871. His wife died later that year, and their adult children auctioned off all the furniture at the inn. Washington William Boyd purchased the deathbed and some other furnishings and later gave them to his brother, Andrew Boyd, a New York City publisher and Lincoln biographer. In 1877, Andrew Boyd found himself in financial trouble and ended up selling the deathbed and other furnishings to Charles F. Gunther, a wealthy confectioner whose success allowed him to collect historic memorabilia. He acquired many Civil War items shortly after hostilities ended and traveled the country looking for what might have been considered junk at the time.

A group of schoolchildren viewing Lincoln’s deathbed at the Chicago Historical Society (now Chicago History Museum), c. 1975. CHM, ICHi-066997

In 1920, the Chicago History Museum (then the Chicago Historical Society) acquired thousands of manuscripts and artifacts from Gunther’s estate, which included materials from the seventeenth century, eighteenth century, and the Civil War. The objects relevant to the Lincoln family are now part of the Museum’s John and Jeanne Rowe Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln Collection. Abraham Lincoln’s deathbed is currently on display at the Museum.

You can see the bed up close or explore our online exhibition A House Divided: America in the Age of Lincoln, which delves into the institution of slavery, the economic development of the antebellum North and West, and traces the antislavery movement and the sectional political controversies that led to war.

Children march in a parade to celebrate Songkran, the Thai New Year, at the Albany Park Community Center, 5101 N. Kimball Ave., Chicago, April 12, 1993. ST-11002573-0007, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

April 13 marks the start of Songkran, the traditional Thai New Year. The holiday was Thailand’s official New Year until 1888 when it was switched to a fixed date of April 1. In 1940, the date of the New Year was changed again to January 1, and Songkran became a three-day national holiday held each April.

Thai immigration to metropolitan Chicago has mirrored national immigration patterns for this Southeast Asian population group. Few Thais came prior to the expansion of US immigration laws in 1965, but steady increases since the 1970s made Thais one of the ten largest Asian groups in the region by the end of the twentieth century with more than 6,000 counted in the 2000 census.

Thai nurses, among the first groups to arrive locally, hosted community gatherings in their homes during the early years and were instrumental in organizing the first notable public event—commemorating the king of Thailand’s birthday in December 1965. Community leaders founded the Thai Association of Greater Chicago in 1969, which incorporated as a nonprofit organization in 1982 and changed its name to the Thai Association of Illinois in 1989. The Thai Association serves both cultural and advocacy functions for the local Thai community and each year sponsors a celebration of the king’s birthday.

A significant number of Thais practice Theravāda Buddhism, along with Cambodians and Laotians. These three communities have established a number of Buddhist temples in the Chicago area, including Wat Phrasriratanamahadhatu (1992) in the Uptown community area, Wat Dhammaram (1976) near the suburb of Bridgeview, and Wat Lao Phothikaram (1982) in Rockford, Illinois.

As in other US cities, Thai settlement has dispersed throughout greater Chicago. Substantial residential presence can be found on the city’s North Side and in northern and southern suburban Cook County, with DuPage County claiming the next highest number of Thais.

Learn more about the history of Chicago’s Thai community in our Encyclopedia of Chicago entry.

In this blog post, Ariel Robinson, Chicago History Museum Research Center page and recent library school graduate, writes about her experience designing a Disability Studies LibGuide for CHM.

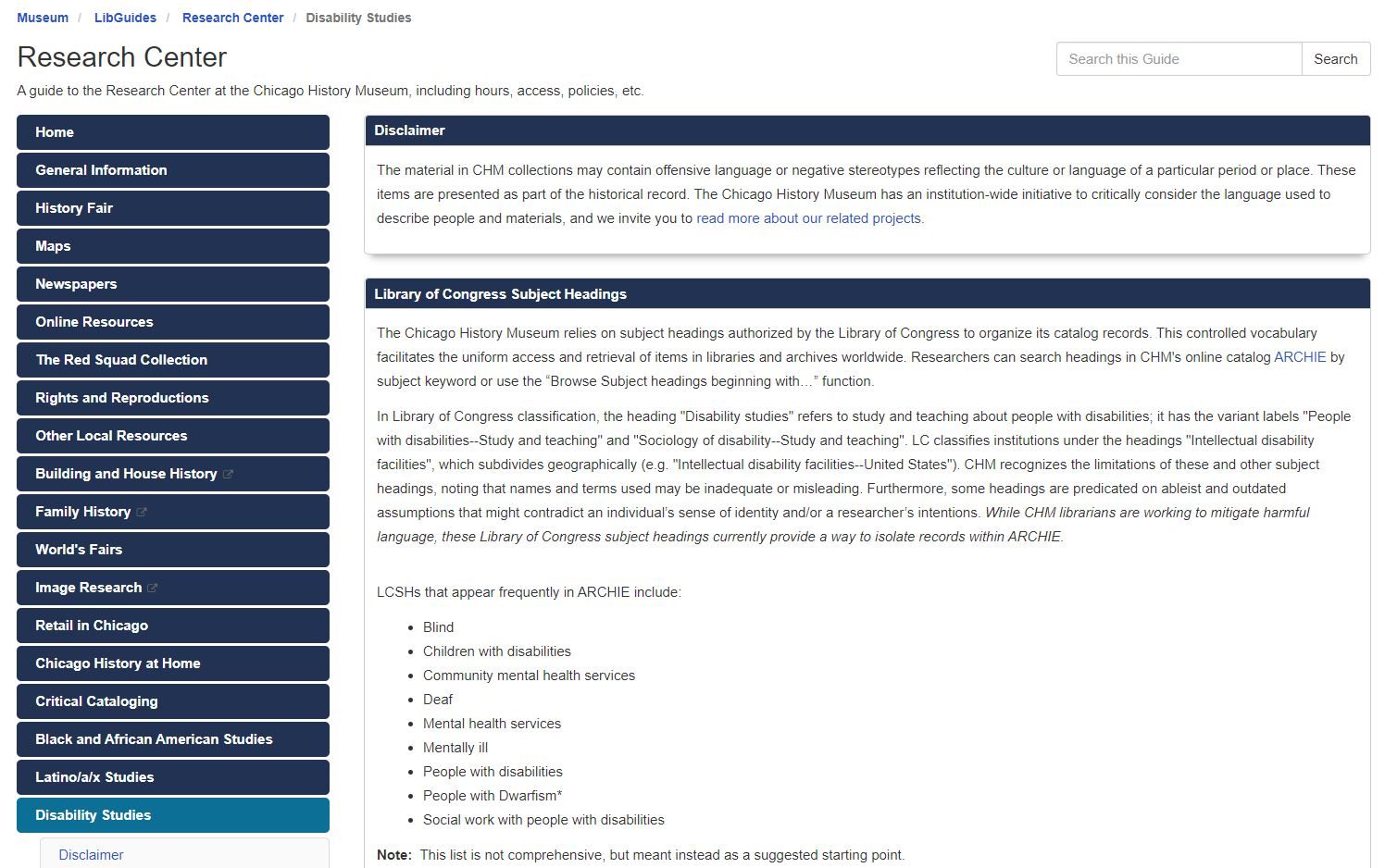

Landing page of CHM’s Disability Studies LibGuide

Landing page of CHM’s Disability Studies LibGuide

At CHM, Gretchen Neidhardt, cataloging and metadata librarian, and Elizabeth McKinley, technical services librarian, have worked on developing LibGuides (subject guides) for various ethnic and BIPOC groups in Chicago as part of larger critical cataloging efforts. Since December 2020, I have been helping draft a LibGuide for Chicago’s disability community. Since I started at the Museum in 2018 as the photocopy assistant in the Research Center, the team has been supportive and enthusiastic about giving me opportunities to gain practical experience in concepts I’ve learned while completing my MLIS. LibGuides are an important and useful tool for reference and instruction.

I began my research with a conversation with Gretchen and Elizabeth about the structure of the guide and their critical cataloging work, which involves updating the keywords and subject headings for works about disabilities to reflect modern changes in language. My research began with works from disability rights activists about museum collections, language choice, and identity. This led me to Project LETS, which describes itself as “a national grassroots organization and movement led by and for folks with lived experience of mental illness/madness, Disability, trauma, & neurodivergence.”

The recorded conversation between Stacey Milbern and Patty Berne, “My Body Doesn’t Oppress Me but Society Does,” and presented by the Barnard Center for Research on Women, broke down the difference between impairment and disability. According to Milbern and Berne, “impairment” is the manifestation of a neurological or physical condition, and “disability” is created by society’s inadequate efforts to create an accessible world through accommodations and design, which imposes barriers on people with disabilities, making it harder for them to fully participate or move within society. I chose to incorporate that difference in language use (see the “Evolution of Language: Disability Identity Terms and Theories” box), in addition to the main content of the guide based on ideas supported by the majority of disability studies scholars.

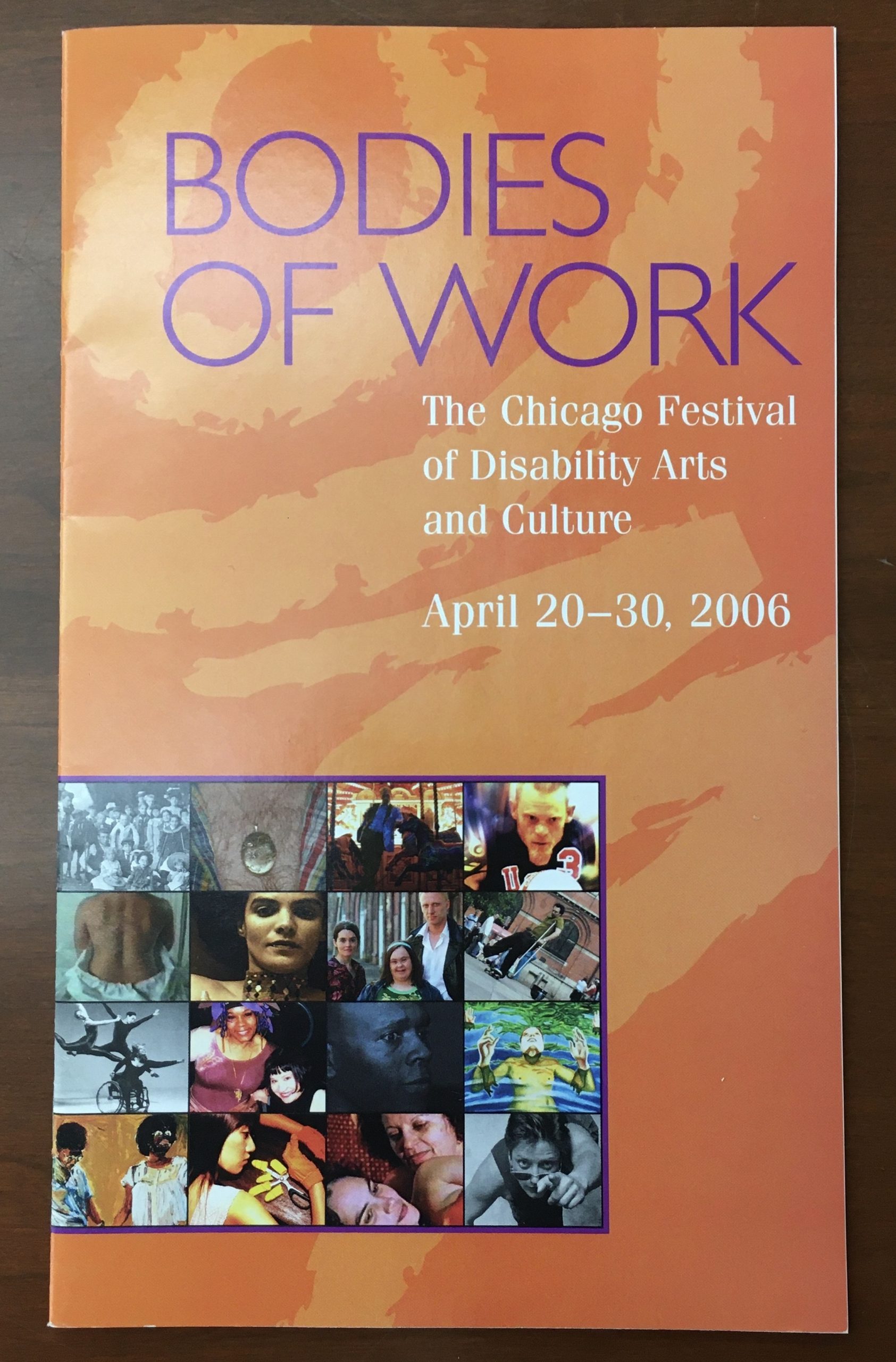

Bodies of Work: The Chicago Festival of Disability Arts and Culture, April 20–30, 2006, Department of Cultural Affairs, Chicago; call number: MB000984

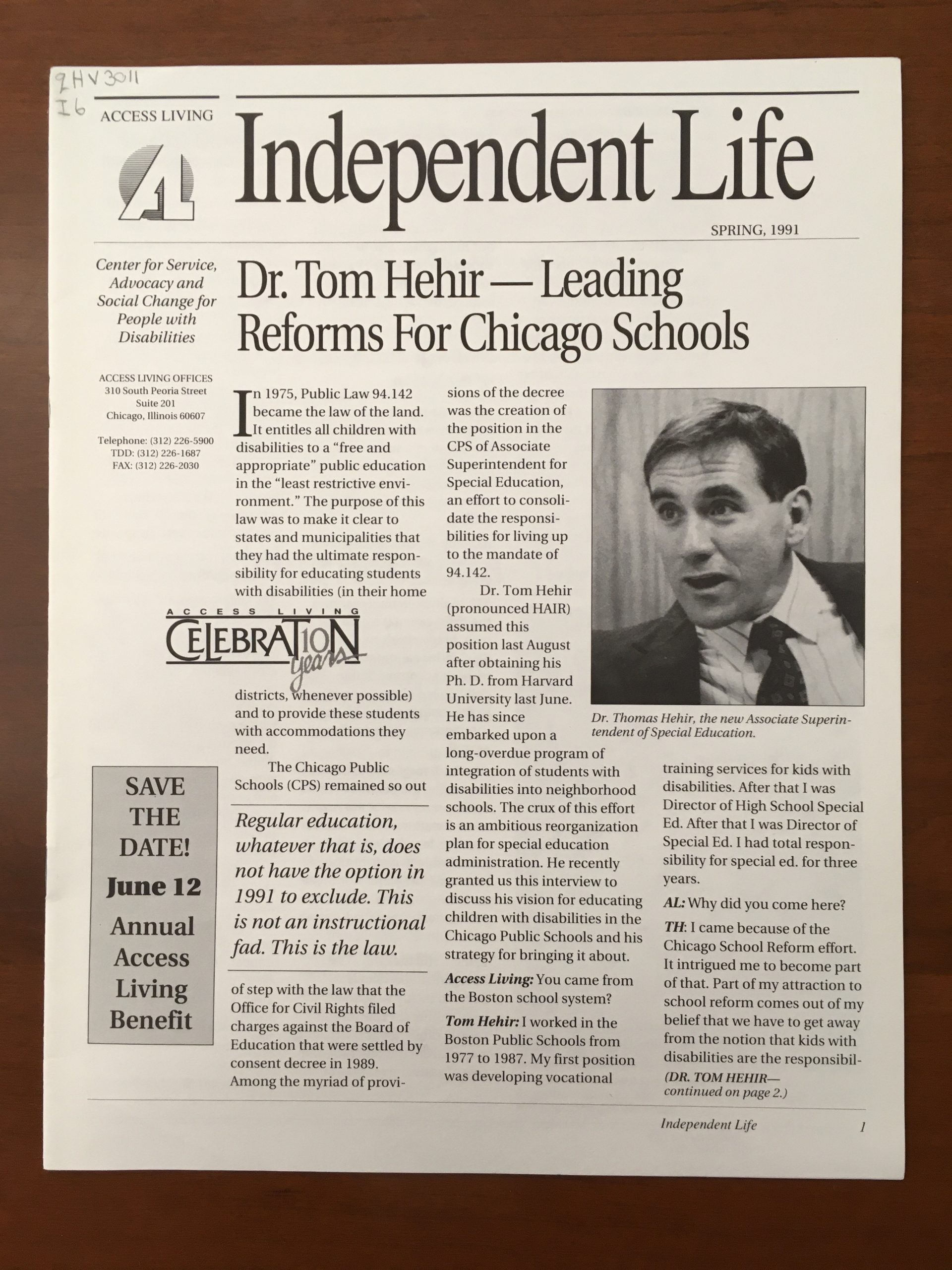

I also included some local organizations that offer resources or influence policies related to people with disabilities in Chicago. For example, Access Living is a local organization that advocates for services such as housing, peer support, and access to transportation. The “Featured CHM Collections” box on the LibGuide links to a Studs Terkel interview with founder Susan Nussbaum. In addition to this interview, there are featured items of each media type available—audio, published material, photographs, and archival collections. (Note: everything but the archival material will still be available while the East Basement undergoes renovations.)

Independent life, Access Living, 1981–1993, Chicago; call number: HV3011 .I6 OVERSIZE

While working on this guide, I found several smaller local initiatives focused primarily on mental health that didn’t quite fit the guide. Some of these were temporary pop-ups such as coffee shops or works in progress through existing organizations.

In addition to adding content to the guide, I also changed the color scheme and layout of the guide to meet web accessibility standards and improve the overall look and feel for all researchers. I used the WAVE extension for Chrome to check the color contrast, compatibility with screen reading technology, and other design functions. All of the Research Center’s LibGuides now have a color scheme that passes WAVE’s color contrast check and fits the museum’s color scheme.

Disability studies covers a variety of lived experiences, and we recognize that we have not captured the full extent here and there is more work to be done. As disability studies scholar and advocate Tobin Siebers asserts in his theory of complex embodiment, “the perception and experience of disability are complex, nuanced, and individual.” We acknowledge that the disability community is not a monolith. It is our goal to collect material in a way that is collaborative, inclusive, intersectional, and expansive. This guide will be continuously updated to reflect new organizations, collections, and other resources. In addition, the guide contains a questions/comments box so readers and researchers can contact us with feedback.

Go to the LibGuide

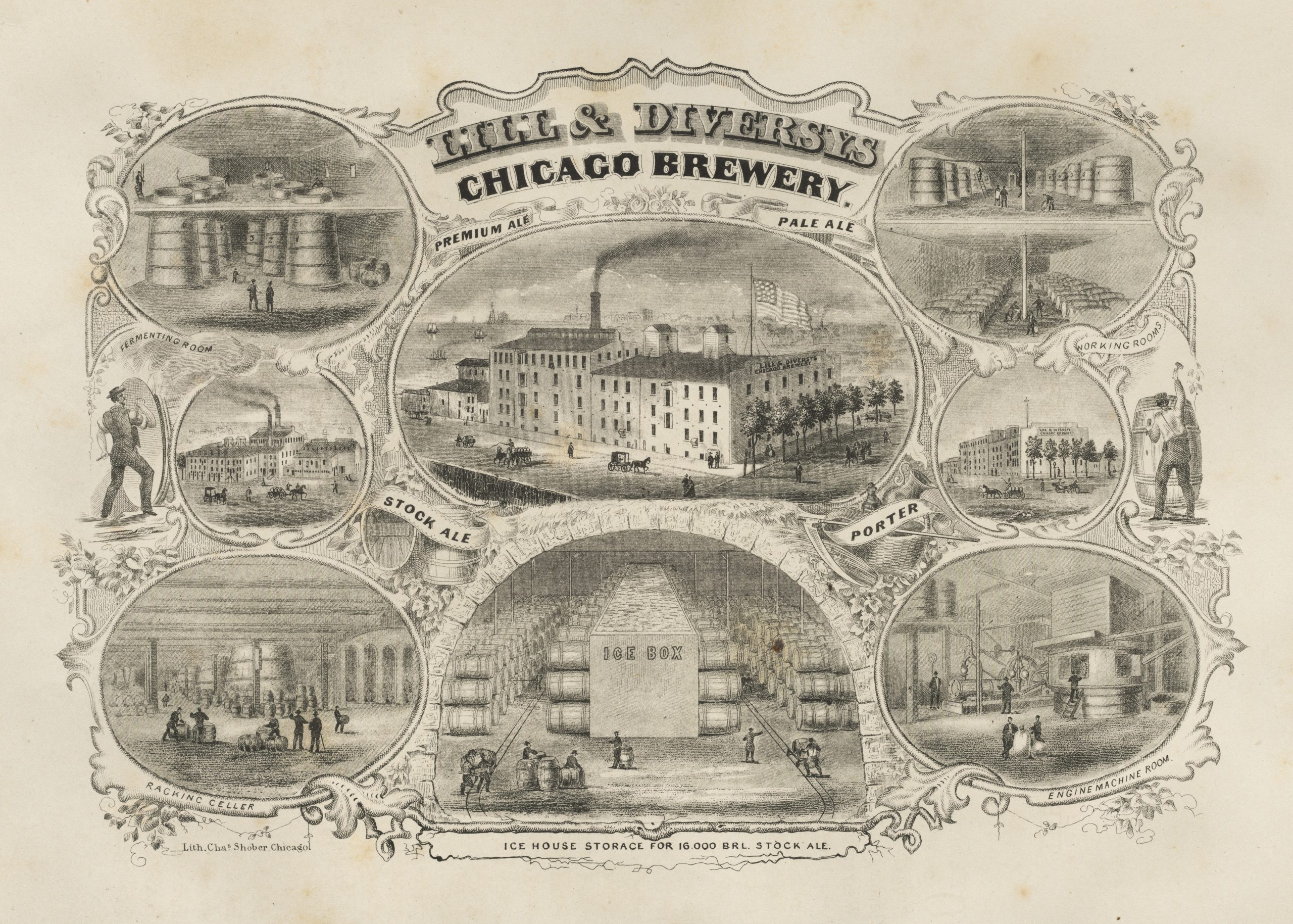

Illustrations of the Lill and Diversey’s Chicago brewery from History of Chicago: Its Commercial and Manufacturing Interests and Industry (1862) by Isaac D. Guyer. CHM, ICHi-089225

For National Beer Day, we hope you enjoy a cold one—if you’re of age, that is. The day is observed on April 7 because on that day in 1933, the Cullen-Harrison Act went into effect, amending the National Prohibition Act and allowing the manufacture and sale of beer and wine with a 3.2% alcohol content or less.

During the nineteenth century, beer making in Chicago was transformed from a small-scale, seasonal activity for local consumers into a highly mechanized big business. Outside of New York City, Chicago became the nation’s largest center of the malt liquor industry.

In 1833, German immigrants established the first brewery in Chicago. Soon renamed the Lill and Diversey’s Brewery (as seen in the illustration), it made English-style ales and porters. From 1860 to 1890, brewing underwent a profound scientific and technological revolution. Louis Pasteur’s work on beer yeast identified germs and other microorganisms as the main reason why such a large proportion of the beer went bad. The near complete domination of the industry in Chicago by German immigrants and their offspring meant that the city became a leading center of “scientific brewing,” boasting a special school, the Siebel Institute of Technology. Successful businessmen such as Conrad Seipp, Peter Schoenhofen, Michael Brand, and Charles Wacker, giants in the brewing community, underwrote the inventions that helped bring refrigeration machines to a point of commercial practicality. They also replaced the traditional brewmeister with university-trained chemists.

The malting business grew in tandem, branching off to form an important industry in its own right. Applying more and more energy in the form of heat, power, and cooling, beer making became one of the country’s most highly automated and mechanized industries, complete with assembly lines in the bottling plant. By 1900, Chicago’s sixty breweries were making over 100 million gallons a year.

Learn more about the history of beer in Chicago in our Encyclopedia of Chicago entry.

It’s National Deep Dish Pizza Day! Where will you be ordering from tonight?

Modern pizza is reputed to have started in Naples in 1889 when Raffaele Esposito created the “Pizza Margherita,” with tomato, mozzarella, and basil replicating the colors of the Italian flag, for King Umberto I and Queen Margherita of Italy. From there, pizza spread across the world. Some late-nineteenth-century Chicago bakeries served pizza, in sheets or in small rolls. Early Italian families served pizza on Taylor Street and the Near South Side.

Chicago-style pizza first appeared in fall 1943 with the opening of Pizzeria Uno. Many GIs had been introduced to pizza as they moved up the coast of Italy, and several Chicagoans anticipated that they would want more when they returned home. Restaurateur and bon vivant Ric Riccardo became partners with Ike Sewell, a liquor salesman, and Sewell’s wife, Florence, who had high-society connections in Chicago, in the new venture. Pizzeria Uno was located a few blocks from the well-known Riccardo’s on Wabash Avenue at Ohio Street. Lou Malnati, Riccardo’s associate manager, was brought over to help run the new establishment.

The Chicago style of pizza was marked by three characteristics: (1) enormous amounts of cheese and a thick, sweet pastry shell crust; (2) very high oven temperatures (600°F) while baking, with plentiful amounts of cornmeal sprinkled in the pan to help insulate the bread; and (3) very long cooking times (fifty to sixty minutes for a medium-sized pie). Such long cooking times allowed patrons time to consume many bottles of Chianti and Lambrusco while waiting.

Newspapers and visitors gave the new restaurant and its new pizza their enthusiastic support. Bolstered by the success of Uno, Sewell opened Pizzeria Due a few blocks away, and Chicago-style pizzerias spread throughout Chicago and the United States.

See more images of Chicagoans enjoying pizza.

Touring Chicago’s Culinary History

Trace the city’s evolution from meatpacking capital to foodie paradise. Our Google Arts & Culture exhibit Touring Chicago’s Culinary History features a selection of menus from our extensive historical collection. From the establishment of the first fine dining restaurant in 1835 to the recent contributions to world cuisine, learn about the origins of Chicago’s status as one of the top food cities of the world.

Left: Caray in the bleachers at the White Sox’s Comiskey Park, October 1, 1981. ST-80004240-0013, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; right: Caray greeting fans and Cubs baseball players and staff at Wrigley Field after recovering from a stroke, May 19, 1987. ST-50004111-0009, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

As the weather warms up, many Chicagoans’ minds turn to baseball. Despite injuries, contract negotiations, and other issues, Sox and Cubs fans always have hope this time of year as a new season stretches out before them.

Harry Caray, longtime Sox and Cubs broadcaster, often spread this early season cheer. Whether handing out beer, taking a shower in the stands, trying to pronounce players’ names backwards, or broadcasting from the bleachers, he made watching and listening fun despite the score or the season’s prospects.

While he did call other professional and some college sports, Caray rose to fame as the St. Louis Cardinals’ broadcaster from 1945 to 1969. He arrived on Chicago’s South Side to announce Sox games in 1971. By 1976, famous Sox owner, Bill Veeck, had Caray singing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” during the seventh inning stretch at Comiskey Park.

With a change in ownership, Caray left the Sox and replaced Chicago baseball legend Jack Brickhouse starting with the Cubs’ 1982 season. Caray’s stardom grew on the North Side. With the Cubbies’ games on WGN-TV’s Superstation, fans across the country heard his renditions of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” from Wrigley Field. Over the years, he hosted numerous celebrities and notable figures in the Cubs’ broadcast booth, including President Ronald Reagan and then First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton. After more than five decades of broadcasting, he died in 1998.

Additional Resources

- Visit the “Wait ’til next year!” section of Chicago: Crossroads of America exhibition to learn more about the history of Chicago sports.

- See more images from Harry Caray’s storied career at CHM Images, which includes opening Harry Caray’s Bar and Restaurant and launching his Holy Cow Sodas soft drink line.

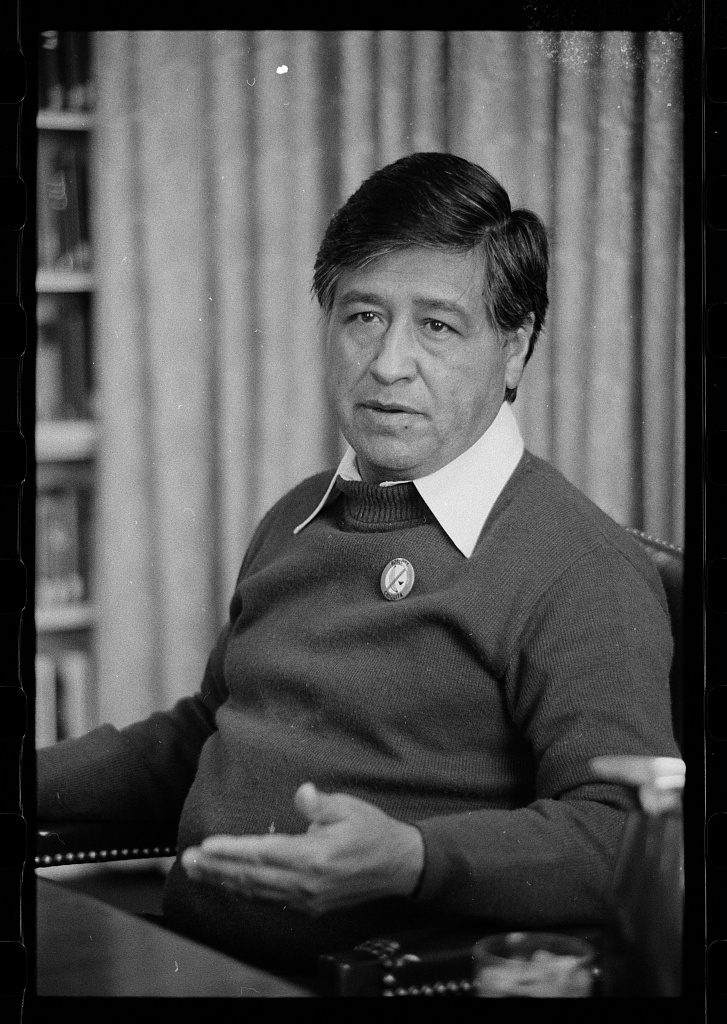

On March 31, 1927, Césario Estrada Chávez was born in Yuma, Arizona, to a Mexican American family. They moved to California in 1938 after his father was swindled out of some land. Both he and his family did field work all around California. Growing up, Chávez and his brother Richard attended thirty-seven different schools through eighth grade. Though he became an advocate for education later in life, he didn’t like school, where he was often forbidden to speak Spanish—the language he spoke at home.

Chávez joined the Navy in 1946 and served two years. In 1948, he married Helen Fabela, and they settled in Delano, California, and started their family. He became involved with the Community Service Organization (CSO) and helped laborers register to vote. Chávez became the CSO’s national director in 1959 but left the position in 1962 to cofound the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) labor union.

In the early 1960s, farmworkers called several strikes to demand higher pay and better working conditions from local grape growers. In 1966, the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) joined forces with the NFWA to form the United Farm Workers (UFW). Together they pushed for contracts with powerful California growers—a nearly impossible feat—by staging a nationwide grape boycott. Boycotters stopped buying grapes, picketed stores that sold nonunion grapes, and spread the word about the cause.

Chávez was instrumental in organizing the boycott, which led to others. Each time, the UFW continued to raise awareness about the working conditions of farmworkers, stressing the dignity of the work and the worker, and connecting farmworkers’ rights to civil and human rights issues. Chavez and other UFW leaders came to Chicago regularly to seek support for their actions, especially from local labor leaders. In 1985, Chávez visited the city to organize boycotts against Jewel stores for selling lettuce from a producer that was hostile to farmworker unions.

Though considered a controversial figure by some, Chávez became an icon for organized labor in the US, the Cesar E. Chávez Multicultural Academic Center in Chicago is named for him, and his birthday is a federal commemorative holiday recognized by nine US states. Learn more about Chávez and the UFW’s grape boycott on our Facing Freedom in America website.

Image: Interview with Cesar Chávez. 4/20/1979. Marion S. Trikosko, photographer. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report magazine photograph collection, LC-U9-37548-32

Studs Terkel Radio Archive

In his forty-five years on WFMT radio, Studs Terkel talked to the twentieth century’s most interesting people. In 1967, he sat down with Chávez to discuss the United Farm Workers effort to gain rights for farm laborers and his childhood that led him to become a labor rights activist.

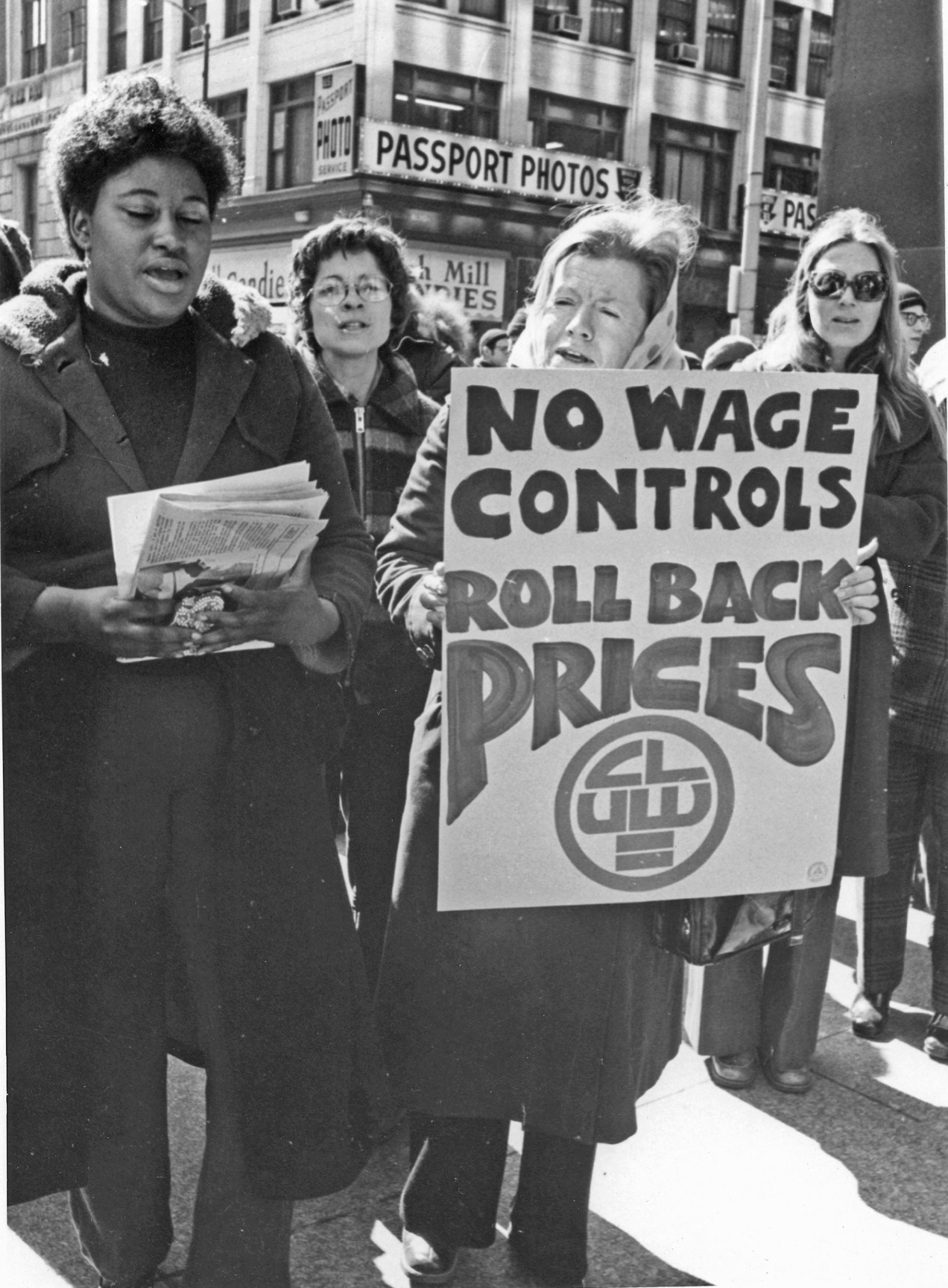

“In all of the major struggles and minor struggles of the organized labor movement, even though history doesn’t always record it, women were there.” —Reverend Addie L. Wyatt

Group of Coalition of Labor Union Women picketers in Chicago, c. 1975. CHM, ICHi-039912

On this day in 1974, the Coalition of Labor Union Women (CLUW) was formed at a founding conference held in Chicago and attended by more than 3,000 union women from around the country. The CLUW sought to organize and empower women by increasing their participation in unions, advance workplace fairness, promote affirmative action, and ensure working women’s voices in the political process.

The formation of the CLUW came about in June 1973 at a meeting of women union leaders, including Olga Madar (the CLUW’s first president) of the United Auto Workers and Chicago’s Addie L. Wyatt of the United Food and Commercial Workers. They had gathered to discuss forming a new group within the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) that specifically gave women a voice in economic issues.

Wyatt battled intersecting gender, racial, and economic injustices throughout her life. Born in Mississippi on March 8, 1924, she and her family moved to Chicago in 1930. She started working as a meatpacker in 1941 and quickly became involved with the United Packinghouse Workers of America union. In the 1960s, she campaigned for Black voting rights in the South and fair housing in Chicago, serving on the action committee of the Chicago Freedom Movement.

Wyatt was also a founding member of the National Organization for Women and supported the Equal Rights Amendment. As a union leader, she fought racial and gender-based workplace discrimination. In 1976, she became international vice president of the United Food and Commercial Workers, making her the first African American woman to hold a leadership position in an international union.

Read more about women’s labor activists in our online experience, Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.

The Chicago History Museum is featuring a collection of many never-before seen works by world-renown photographer Vivian Maier in an upcoming exhibition, Vivian Maier: In Color, opening to the public May 8, 2021.

“The Chicago History Museum is committed to sharing Chicago stories, and Vivian Maier’s work represents her private contributions to the documentation and representation of culture found within city life,” said Charles E. Bethea, Andrew W. Mellon Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs. “Maier’s photography brings a glimpse of Chicago and its residents to life between the 1950s to the 1970s, allowing present day visitors the opportunity to reflect on the striking parallels it has to today’s society.”

Maier worked as a nanny to several Chicago families and took extensive photos, documenting intimate moments of the city and its people. Vivian Maier: In Color will illuminate Maier’s unique portfolio. While her focus of attention varied, she approached all of her work with unwavering confidence, revealing parallels, intersections and tensions.

Following her death in 2009, Maier’s prolific photographs previously discovered in her abandoned storage locker were first displayed for the public. Maier rose to posthumous international acclaim for her photography that expertly documented the people, landscapes, light, and development of New York, her hometown, and Chicago where she settled, with remarkable attention to detail. Maier’s work is now used widely in research and curriculum and has been celebrated in at least 42 exhibitions around the world, including one on display at the Chicago History Museum from 2012-2017, Vivian Maier’s Chicago.

To underscore her accomplished photography, Vivian Maier: In Color will feature more than 65 color images from the 1950s-1970s, most of which have never been seen, from art collectors Jeffrey Goldstein, John Maloof, and Ron Slattery. It is the first time the work in these three collections have been featured together in one exhibition. The exhibition will also include clips from film, made by Maier, and a series of sound bites and quotes featuring Maier’s voice.

“Vivian Maier’s photographs show moments of what looks to be a dynamic, multifaceted life in which she prioritized her passion for taking pictures,” said Frances Dorenbaum, curator of Vivian Maier: In Color. “Her dedication to photography is what makes her work so prolific today, and the Chicago History Museum is thrilled to share her voice with the public and celebrate a once unknown artist.”

The exhibition comes after the Chicago History Museum last year acquired nearly 1,800 Vivian Maier color slides, negatives and transparencies from Chicago-based artist and art collector Jeffrey Goldstein. The collection primarily depicts people and scenes in Chicago from the 1950s-1970s. The museum worked closely with Goldstein and Vivian Maier’s Estate to accept a donation of photographs and preserve them for public use. The acquisition gives the public access to many never-before-seen images on the Museum’s image portal.

The Chicago History Museum received a grant from The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation to process the Vivian Maier collection. The grant promotes long term preservation, collections access and interpretive digital output such as blog posts and an online exhibition.

To learn more about Vivian Maier: In Color and associated programs, please visit: www.chicagohistory.org/exhibition/vivian-maier-in-color/