Latest Posts

Chicago has had more than its fair share of big band and jazz dance halls across the city to accommodate nearly everyone’s musical taste. On December 6, 1922—100 years ago—at 62nd Street and Cottage Grove, in the Woodlawn neighborhood, the Trianon Ballroom opened its doors and counted itself among the city’s nightlife destinations.

An undated photograph of the exterior of the Trianon Ballroom at Cottage Grove and East 62nd Street. The marquee reads: “Presenting Art Kassel & His Orchestra.” CHM, ICHi-050765

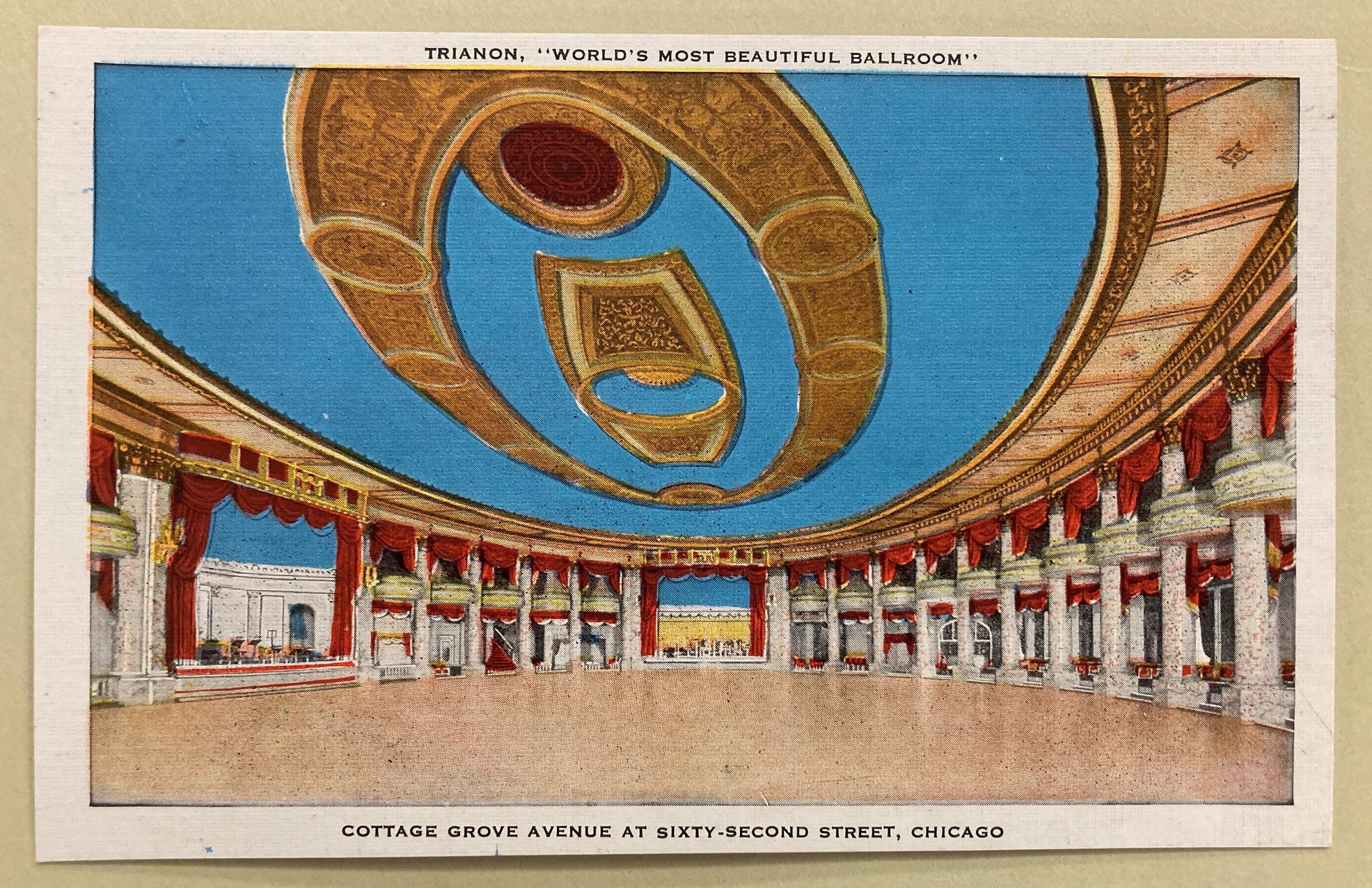

Marketed as the “World’s Most Beautiful Ballroom,” its name and décor were inspired by the Grand Trianon palace at Versailles, commissioned by Louis XIV. The dance hall was an enterprise of brothers Andrew and William Karzas, entrepreneurs in Chicago’s Greek community, who already owned a small chain of movie theaters across the city. When it opened, the Trianon was said to be able to accommodate up to 3,000 dancers at a single time on the main ballroom floor, which measured 100 by 140 feet. The venue also boasted being one of the few air-conditioned facilities in all of Chicago. When all was said and done, the estimated cost of opening the ballroom was $1.2 million (close to $21.3 million in today’s dollars). The venue’s opulence reflected its entertainment, as it brought the most popular names in big band and attracted Chicagoans from every walk of life, from working-class couples to elite socialites. In 1920s Chicago, the Trianon was the place to be.

Undated postcard of the “World’s Most Beautiful Ballroom.” Photograph by CHM Staff

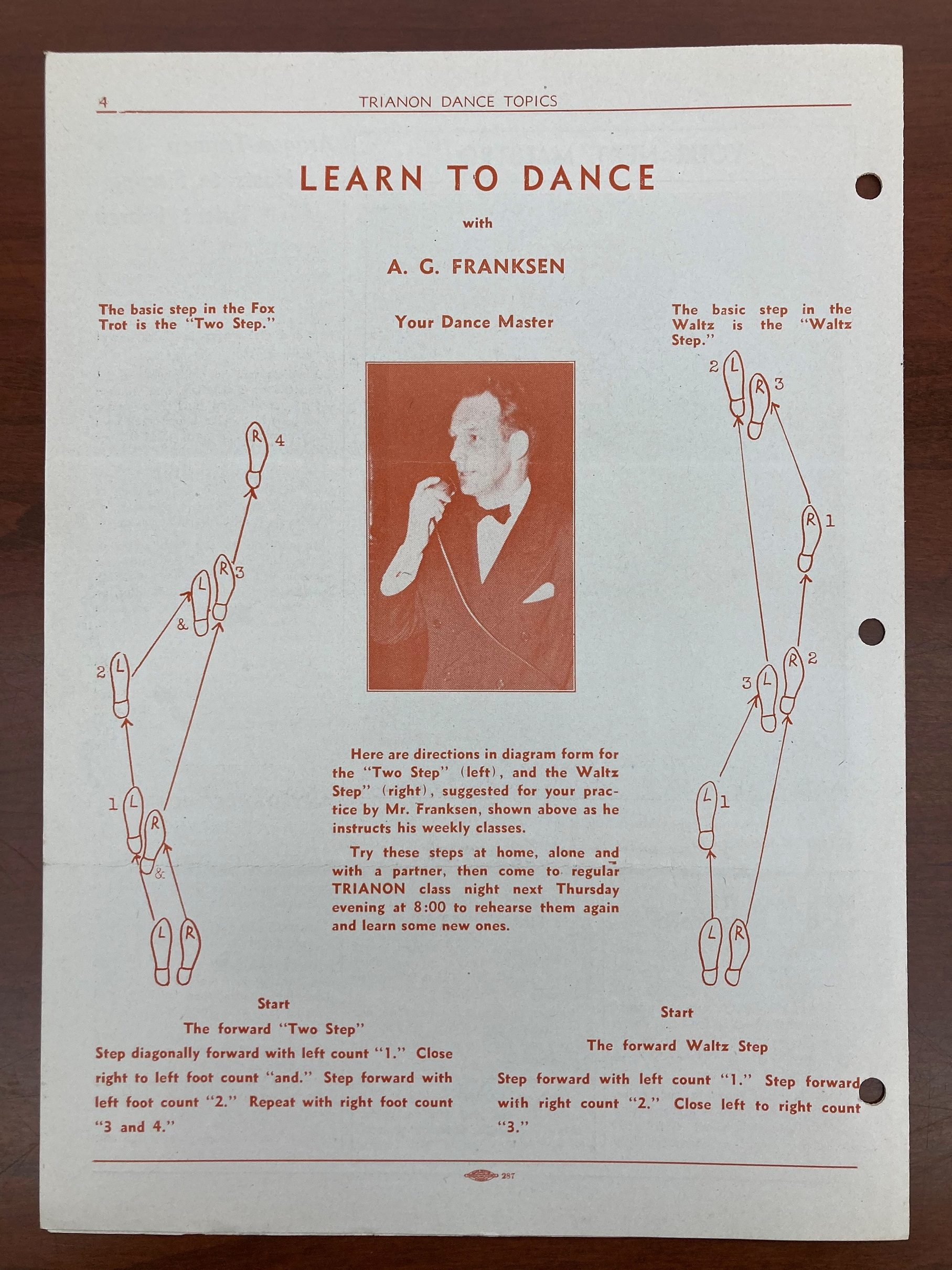

To match its aesthetic reputation, the Trianon would be the first venue in the city with a strict dress code—coats and ties for gents, gowns for ladies. To enforce “appropriate” behavior, the venue employed a troop of “floor men” who were tasked with policing the room, keeping an eye out for dancers engaging in lewd or overly physical displays of affection. And for those with insufficient knowledge or two left feet, weekly dance classes were also held on-site. Of course, if patrons wanted to dance the jitterbug or dance along to some jazz, they’d be disappointed to know about the Trianon’s strict policy forbidding both.

Undated photograph of marble columns around the dance floor in the Trianon Ballroom at Cottage Grove and E. 62nd St. CHM, ICHi-050746

The success of the Trianon would inspire the Karzas brothers to try and catch lightning in a bottle twice with the opening of Trianon’s sister ballroom, the Aragon, four years later in 1926, which still operates to this day. Beyond big band dances, the Trianon would go on to have its own radio station, with the call letters of WMBB standing for “World’s Most Beautiful Ballroom.” The station went on the air in 1925, hoping to capitalize on the good reception the ballroom had received. The airwaves, however, were not meant to be and the station went permanently dark in 1928.

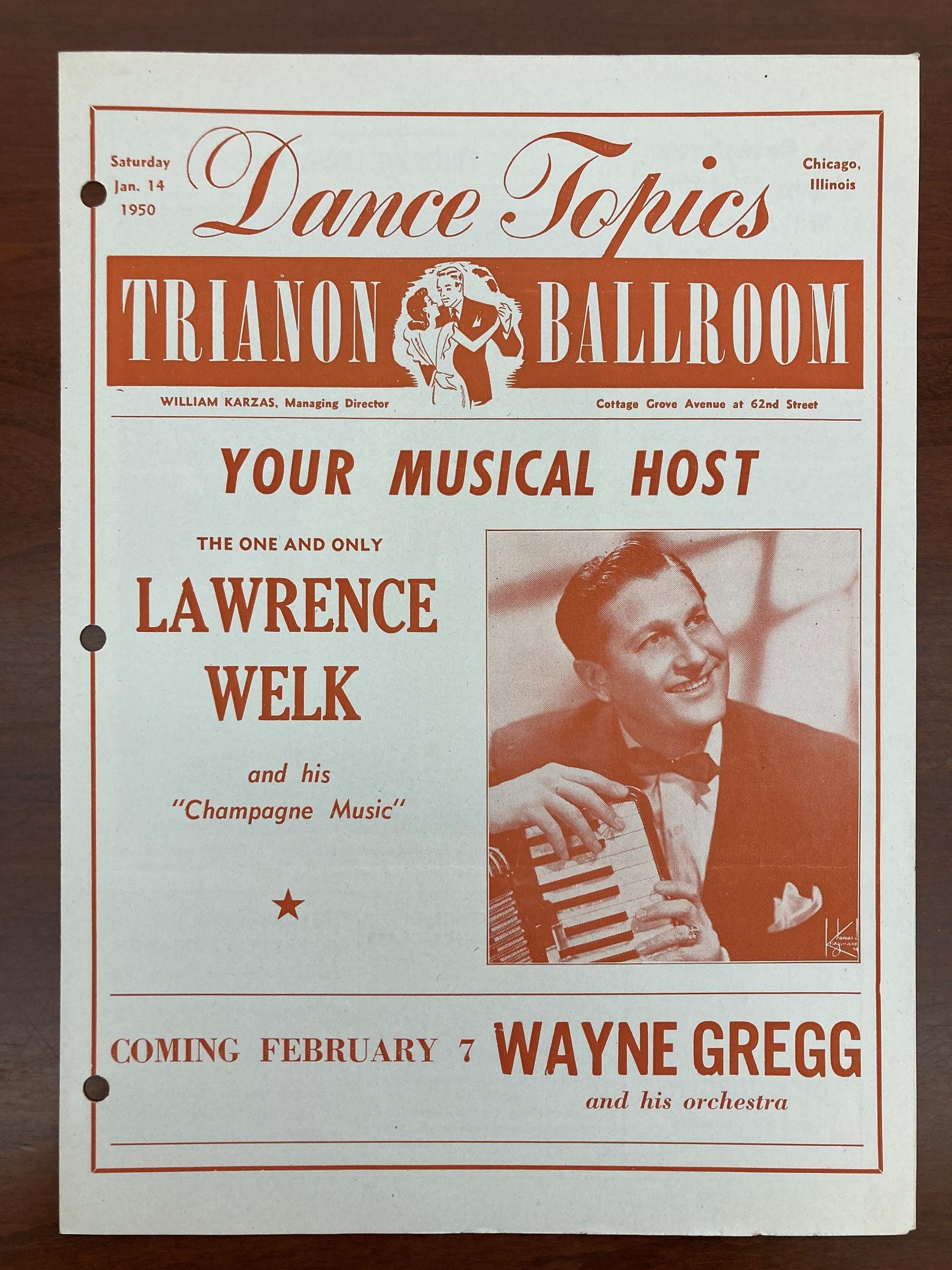

Front and back cover of “Dance Topics, Trianon Ballroom,” featuring Lawrence Welk and the basic steps of the foxtrot, January 14, 1950. Photograph by CHM Staff

Popular as it was, the Trianon was not without its failures, many of which would ultimately lead to its closing in 1958. For one, from the moment the doors opened, the Trianon served a strictly white clientele, which would open the doors for competitors catering to the South Side’s growing Black clientele, a market share that would only grow larger as white flight from the area steadily increased. The declining interest in ballroom dancing certainly didn’t help the once great venue’s ailing status.

Bobby Bland performing at the Trianon Ballroom, 6201 S. Cottage Grove Ave., Chicago, December 7, 1963. CHM, ICHi-138947; Raeburn Flerlage, photographer

After it closed, there was an effort to revive the dance hall under new management and a new name (now going by El Sid), but the rebrand was ultimately doomed to fail. At some point, as evidenced by photographs in the Museum’s collection, the Trianon opened its stage to Black performers and ensembles, but by then, it was far too late. The building that was home to the venue would ultimately be demolished in 1967 to make room for low-income housing.

View of guests attending Queen of Finnie’s Annual Masquerade Ball at the Trianon Ballroom, 1958. Guests in attendance included donor James C. Darby and members of Chicago’s gay community. CHM, ICHi-176136; James C. Darby, photographer

The legacy of the Karzas brothers would continue beyond the Trianon and the Aragon, with Andy Karzas, who became the eventual owner and operator of the Aragon by the early 1960s but would go on to be better remembered for his role as an on-air personality and opera virtuoso for WFMT. He passed away in 2011 at the age of 77.

Additional Resources

- Learn more about Chicago’s history of dance halls in our Encyclopedia of Chicago entry.

- Listen to Andy Karzas discuss both the Aragon and the Trianon in a 1963 interview with Studs Terkel.

- See more of James C. Darby’s photographs in our Google Arts & Culture story Drag in the Windy City

- Read the 1973 Chicago History article “The World’s Most Beautiful Ballrooms”

- Visit the Abakanowicz Research Center to see more photographs and ephemera from the Trianon Ballroom

This post is from Marissa Croft, CHM’s research and insights analyst and author of our Fashion and Costume Research Guide. As a PhD candidate at Northwestern University, she also researches the clothing of the French Revolution and women’s clothing reform movements of the 19th century.

As December dawns, many Chicagoans may find themselves fondly reminiscing about making a special seasonal trip to Marshall Field’s department store to experience its yearly transformation into a holiday wonderland. The decorated State Street windows and the record-breaking Christmas tree of the Walnut Room were not only intended to spark wonder and delight from visitors, but long-term brand loyalty. Field’s commitment to elevating the Christmastime retail experience through art was in large part fostered by an artist named Clara Powers Wilson, who served in many roles at the store, including working as the art director of the company’s most successful publication, Fashions of the Hour.

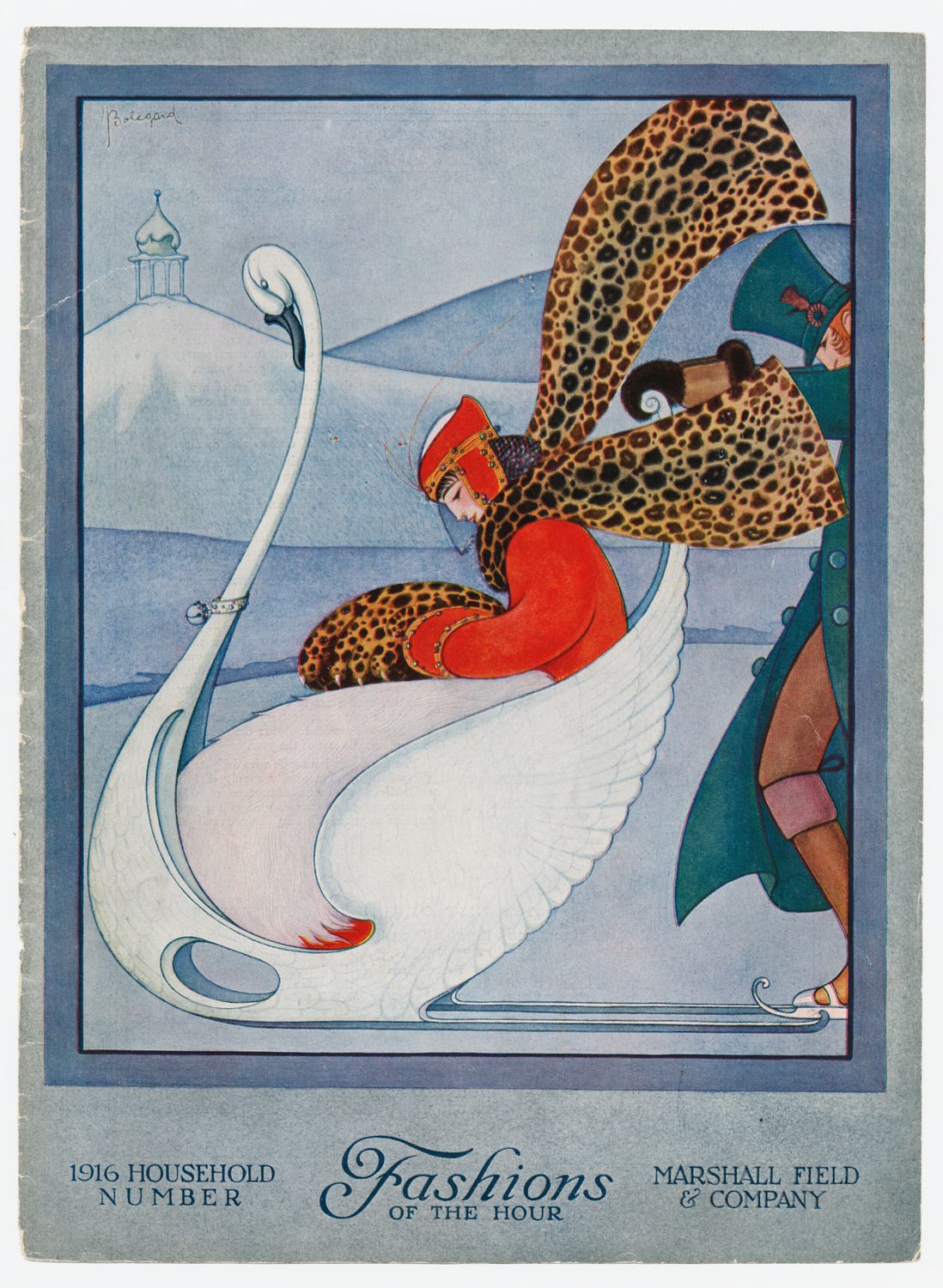

Cover of Marshall Field’s Fashions of the Hour, 1916. CHM, ICHi-073734

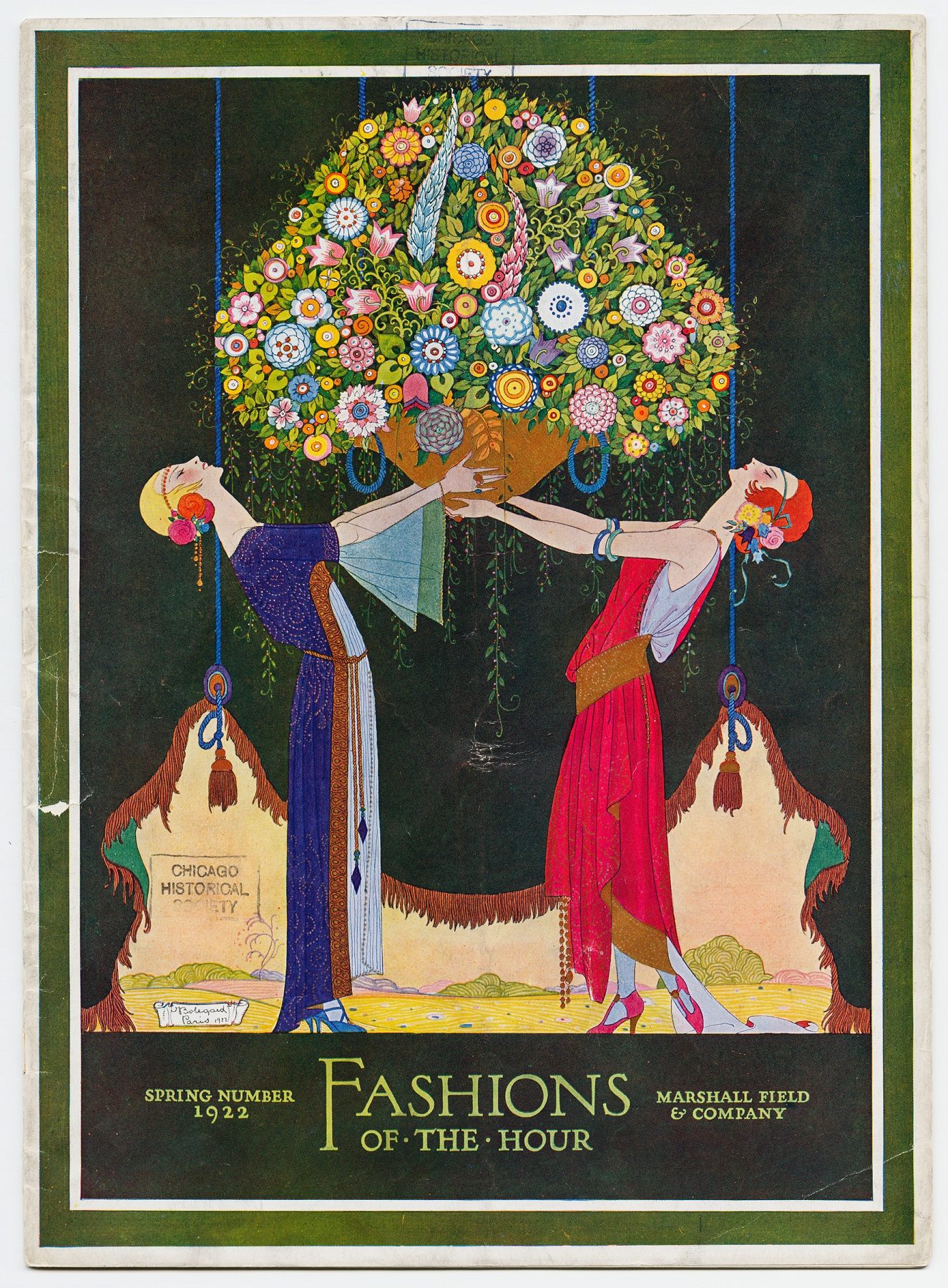

The first edition of Fashions of the Hour came out in October 1914 and the magazine ran until 1978. Initially, a copywriter named René Mansfield was the sole editor of the publication, but Clara Wilson soon joined her as art director, and it was during Wilson’s tenure that the publication reached its artistic peak. Fashions of the Hour set itself apart from other commercial catalogs in several ways. First, it was published six times a year and featured lavishly colored covers and interior illustrations by some of the most famous French and American Art Deco artists of the era. Second, they sold no space to advertisers, which meant every page of the twenty-to-forty-page magazine could be completely devoted to illustrations of store products, articles about art and society in Chicago, short literary pieces, travelogues, and photographs of famous people dressed in the latest fashions. Finally, the magazine was free, and its peak circulation in the mid-1920s reached over 100,000 people. Without the benefit of paid ads, it cost Marshall Field’s roughly $250,000 annually to publish.

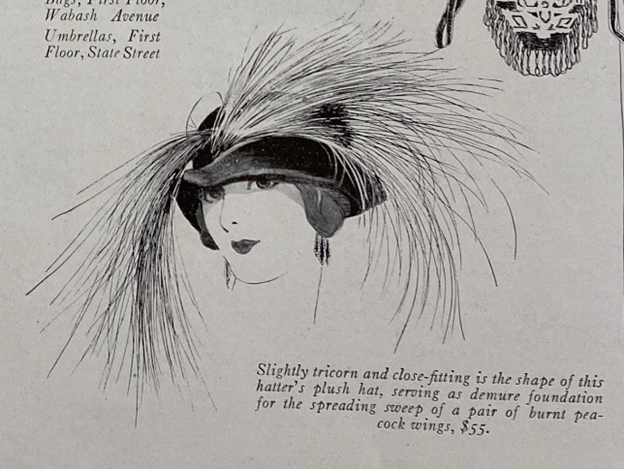

An example of the product illustrations that were featured in the magazine. From the Autumn 1922 issue: “Slightly tricorn and close-fitting is the shape of this hatter’s plush hat, serving as a demure foundation for the spreading sweep of a pair of burnt peacock wings, $55.” (In 1922, $55 had the same purchasing power as $972 in 2022.) Photograph by CHM Staff.

Wilson’s leadership of Fashions of the Hour was just one of many of her contributions to retail history, however. Born in 1873 in Michigan as Clara Powers, she studied under James McNeil Whistler at the Whistler School in Paris and the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1898, she married Louis William Wilson, a fellow artist who worked as an instructor of color theory at the Art Institute. Wilson started her career as a freelance artist around the same time, specializing in illustrating children’s books and designing illustrated journals for recording recipes, addresses, and memories.

An illustration by Wilson for Cheery and the Chum, a children’s book published in 1908. Library of Congress Public Domain Archive.

Wilson’s career at Field’s began in 1914, when she was hired to serve as the indoor counterpart to Arthur Fraser, the artist responsible for creating the year-round State Street window displays. Her job was to select draperies, decorations, and lighting effects for everywhere in the store’s interior except the main aisle and light wells (also Fraser’s territory). When she insisted on covering the up the expensive, solid mahogany paneling in the Women’s Salon to achieve a more flattering lighting scheme for the patrons trying on clothing, general manager David Yates objected, and she was sent to serve a stint in the advertising department.

Cover of Marshall Field’s Fashions of the Hour, Spring 1922. CHM, ICHi-051295

Charged with the art direction of Fashions of the Hour and with increasing traffic to neglected areas of the store, Wilson turned her eye first to the housewares department. She proposed holding cooking classes in the store, rearranging the stock, and even pushing utensil manufacturers to paint implement handles different colors so shoppers could match them to their kitchens. These efforts were so successful that she and her two assistants were soon given free reign over the presentation of merchandise throughout the store. In 1916 Wilson was appointed the first official Christmas tree designer, and she quickly set the precedent for the level of lavish seasonal decorations that would persist at Field’s until it was purchased by Macy’s in 2006.

Christmas tree at the Marshall Field’s Walnut Room, 1966. ST-40002977-0001, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Wilson’s career did not slow, even after the unexpected death of her husband in 1919. In late 1922 she moved to New York with her four children to serve as the managing editor of Harper’s Bazaar. To the surprise of many, she returned to her position at Field’s a few years later, and immediately began advocating for even more drastic changes to the way merchandise was displayed. Continuously drawing on her artistic background and deep understanding of color theory, Wilson noted in a 1946 interview that during the late 1920s she was the one who “had the idea to bunch associated articles” and that she also “introduced match colors so a customer could have an ensemble of color.” Perhaps her most daring move was taking one of Fraser’s window display mannequins and putting it inside the store underneath a spotlight that many feared would scorch the dress.

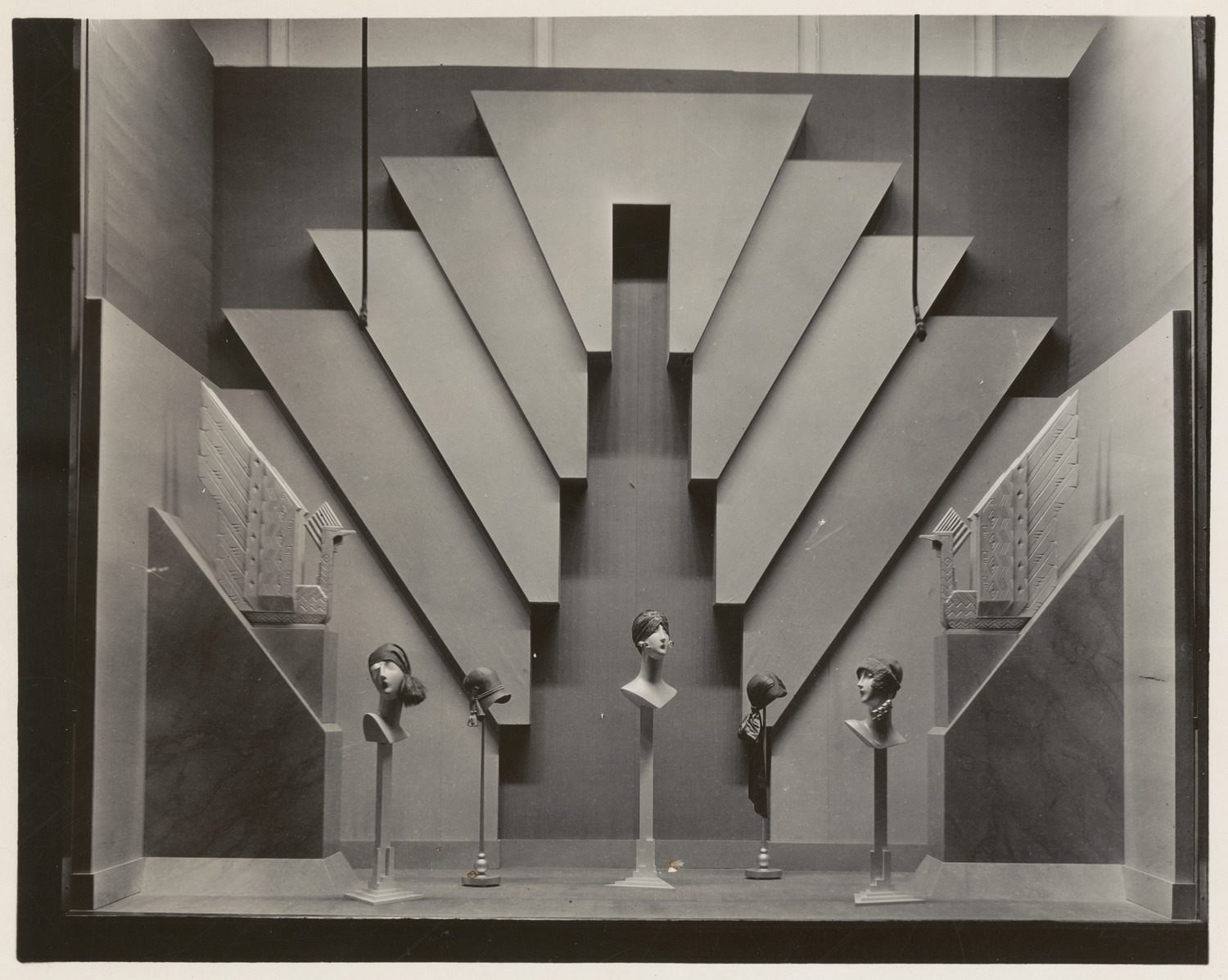

A Marshall Field’s display for hats circa 1928 featuring Art Deco-inspired sculptures and backdrop. CHM, ICHi-092922, Marshall Field and Company archives. Gift of Federated Department Stores.

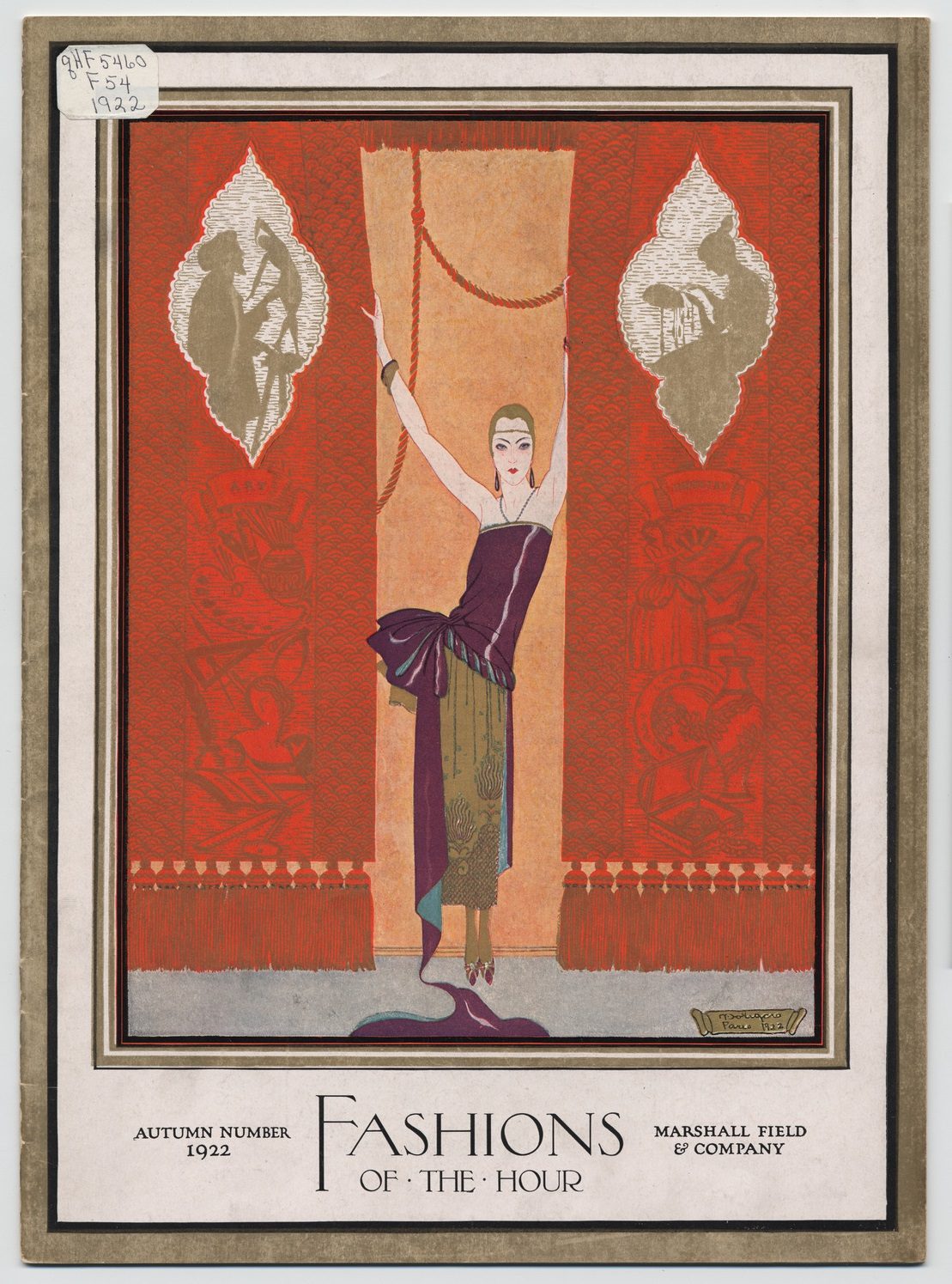

The Autumn 1922 edition of Fashions of the Hour was one of the final issues of the magazine that Wilson oversaw before departing for New York and it was dedicated to highlighting the intersections of art and industry. In one article, Robert B. Harshe, the director of the Art Institute of Chicago, noted that “a product is not finished today unless the element of beauty as well as the element of utility is present.” Wilson’s work at Field’s was the embodiment of this philosophy. From catalogs to kitchen implements, she expertly blended form and function to elevate these common commercial goods into artistic objects.

Marshall Field’s Fashions of the Hour, Autumn 1922. Note that the themes for the issue, “art” and “industry,” are subtly illustrated on the two curtains in the image. CHM, ICHi-040590

Additional Resources

- View more images of Fashions of the Hour

- See the Federated Department Stores’ records of Marshall Field & Company, c. 1852–2004, at the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit

- Order Fashions of the Hour prints from the CHM PhotoStore

Sources

- Art Deco Chicago: Designing Modern America (Chicago Art Deco Society, 2018)

- Emily Kimbrough, Through Charley’s Door (Harper & Row, 1952)

- Encyclopedia of Chicago, “Field (Marshall) & Co.” (Chicago History Museum, 2005)

- William Leach, Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture (Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2011)

- Lloyd Wendt, Give the Lady What She Wants!: The Story of Marshall Field & Company (And Books, 1979)

This year, National Bible Week began Sunday, November 20, and ends on Saturday, November 26, 2022. To mark the occasion, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman highlights a remarkable illustrated publication in CHM’s collection.

National Bible Week originated in 1941 under US president Franklin D. Roosevelt, when founders of the National Bible Association read scripture over the radio to bring comfort to nationwide audiences in the midst of World War II. The week-long commemoration continues today by recognizing the historic importance of scriptural text and encouraging its reading as a source of hope.

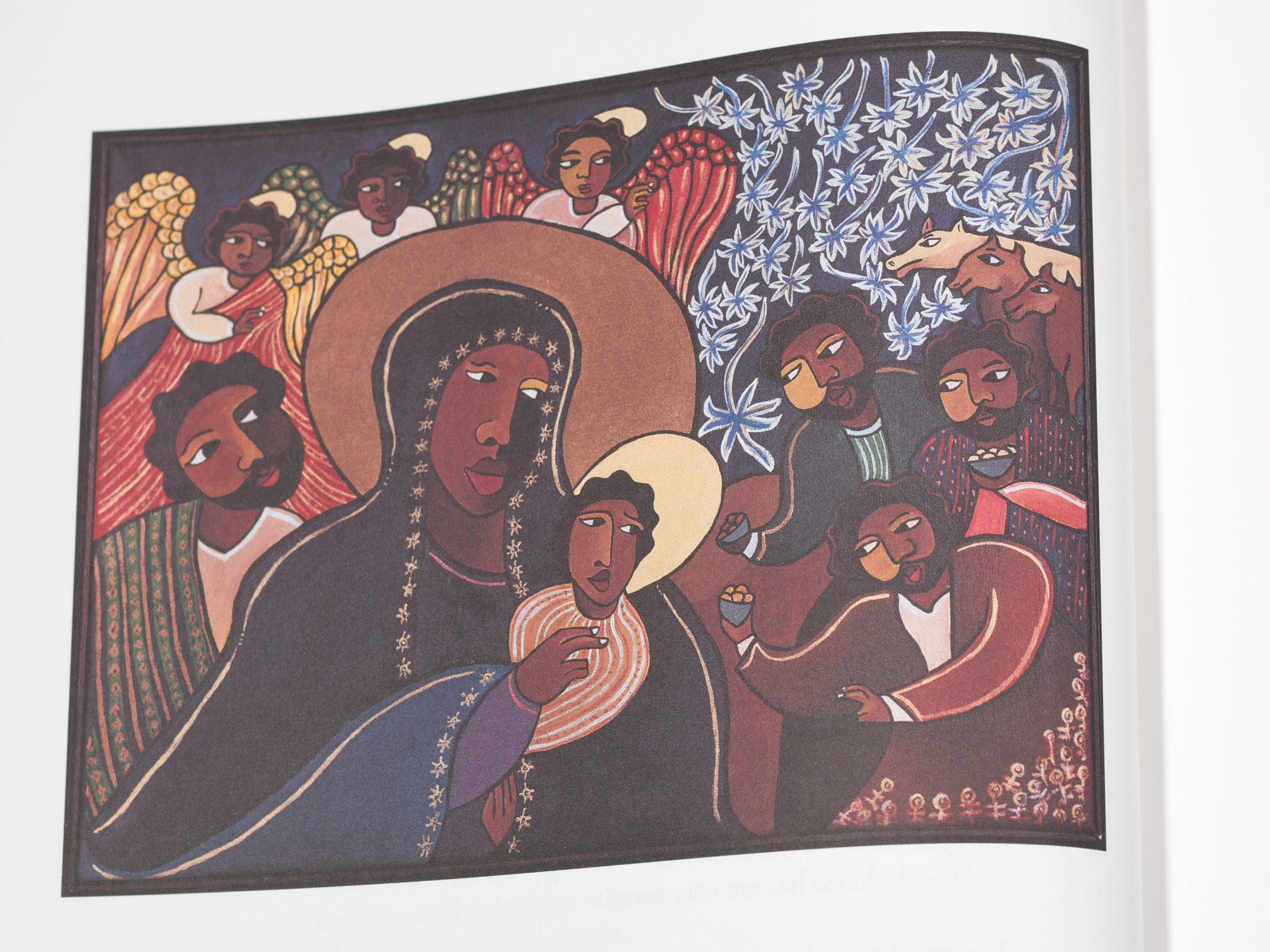

Joseph, Mary, and Jesus visited by the Three Wise Men. The Book of the Gospels. Chicago: Liturgy Training Publications, 2001. Photograph by Timothy Paton Jr.

An important aspect of reading scripture is an emphasis on seeing yourself in the text through the stories being told. In addition to the actual words written, this connection can also happen through images used to depict different figures, scenes, and moments. Biblical illustration is a practice that has spanned thousands of years. In American visual tradition, this has often been done through a racialized lens that depicted biblical figures as white or of European origin to the exclusion of others. There is also an historic tradition of reclaiming Jesus and other saints as people of color with culturally specific connections and community-centered meanings. In Painting the Gospel: Black Public Art and Religion in Chicago, Dr. Kymberly Pinder describes this as an important reconciliation process for empowering, uplifting, and creating a sense of belonging for Black religious leaders and community members.

The front cover of The Book of the Gospels features an angel, representing Matthew, and a lion, representing Mark. Photograph by Timothy Paton Jr.

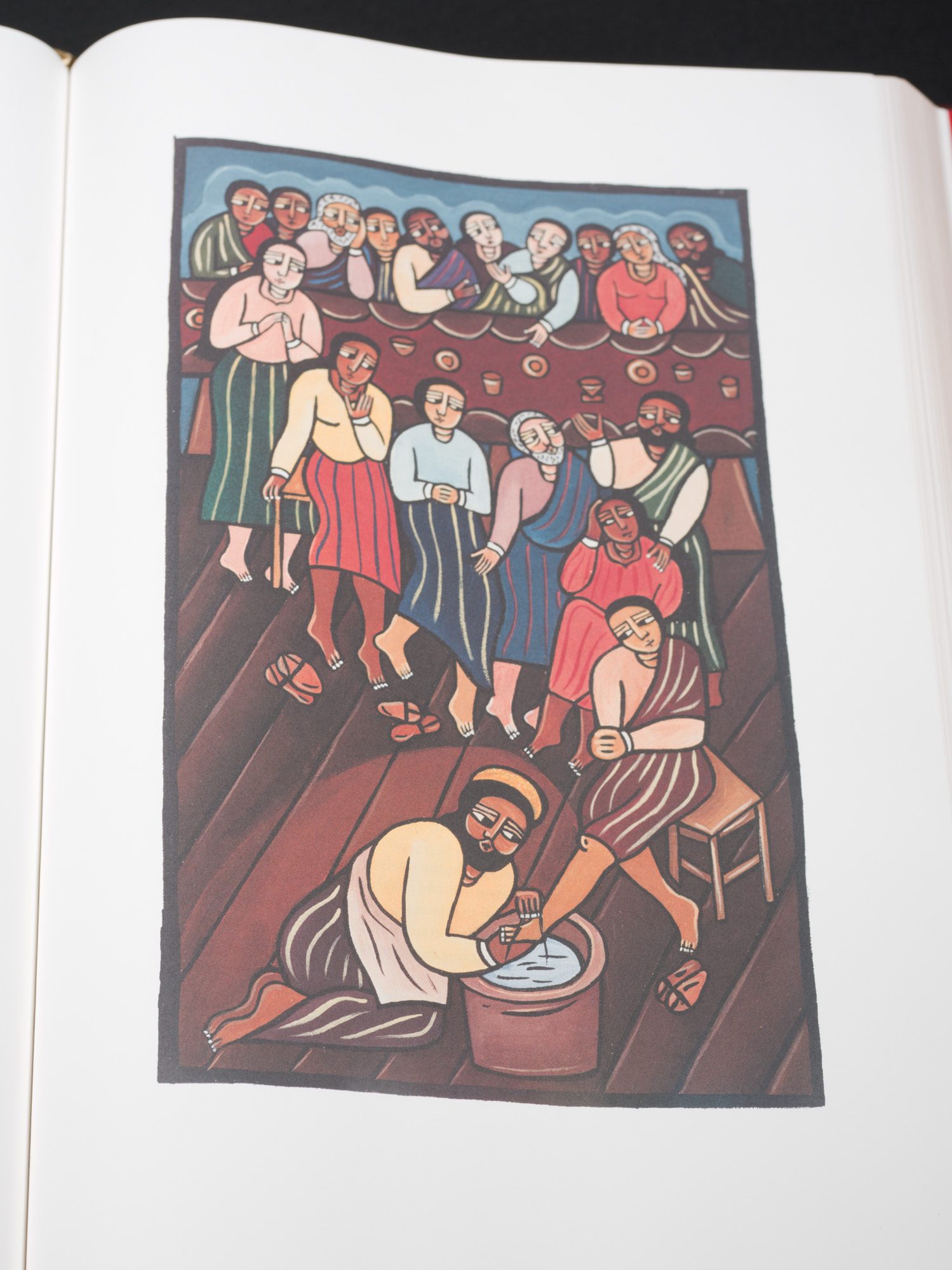

In recognition, we turn to this beautifully illustrated text published by Chicago-based Liturgy Training Publications. Released in 2001, The Book of the Gospels focuses on four books of the Christian New Testament: Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. Each book, through a slightly different lens, tells stories from the life of Jesus of Nazareth. These also correspond to different rituals and celebrations throughout the Christian year. The Gospels’ cover is richly decorated with emblems symbolizing their four writers: Matthew as a human/angel, Mark as a lion, Luke as an ox, and John as an eagle. On the pages inside, important moments in the text are highlighted through a series of paintings by Bronx-based artist and curator Laura James.

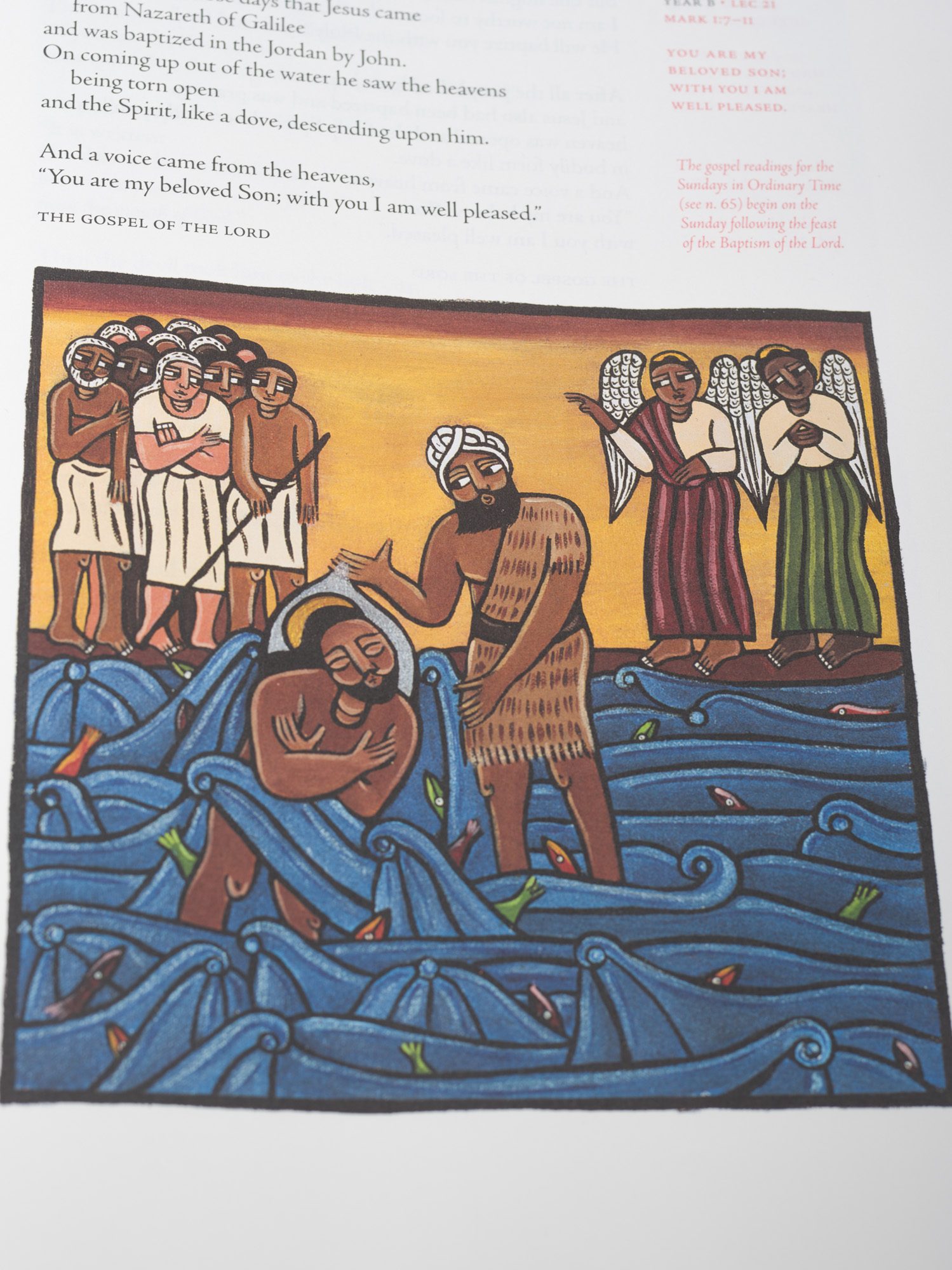

The Baptism of Jesus by John the Baptist in The Book of the Gospels. Photograph by Timothy Paton Jr.

James’s paintings draw inspiration from the Ethiopian Christian tradition utilizing lush colors, strong lines, and rich pattern work to bring biblical scenes into focus. Important to this is the centering of Black and Brown figures as protagonists.

Jesus washing the feet of the disciples in The Book of the Gospels. Photograph by Timothy Paton Jr.

As described on her website, “James is pleased to help black people see themselves in their sacred texts, in African religions and Christianity, a place where racialized people have been excluded in the west.” In her larger practice, James’s work ranges from secular to sacred and includes religious imagery from many different faith traditions, including Christian, Yoruba, Buddhist, Islamic, ancient Egyptian, and Divine Feminine themes, all done in a similar stylized way. In The Book of the Gospels, her images demonstrate the Christian idea of imago Dei (the image of God) as something that is universal yet specific and, ultimately, embodied through multicultural human experience.

Bank of America will support the Museum’s goal to represent Latino/a/x communities in an ongoing, sustained way. Specifically, the funding will fuel the Museum’s youth workforce development opportunities for Chicago’s Latino/a/x communities and its commitment to elevating overlooked history.

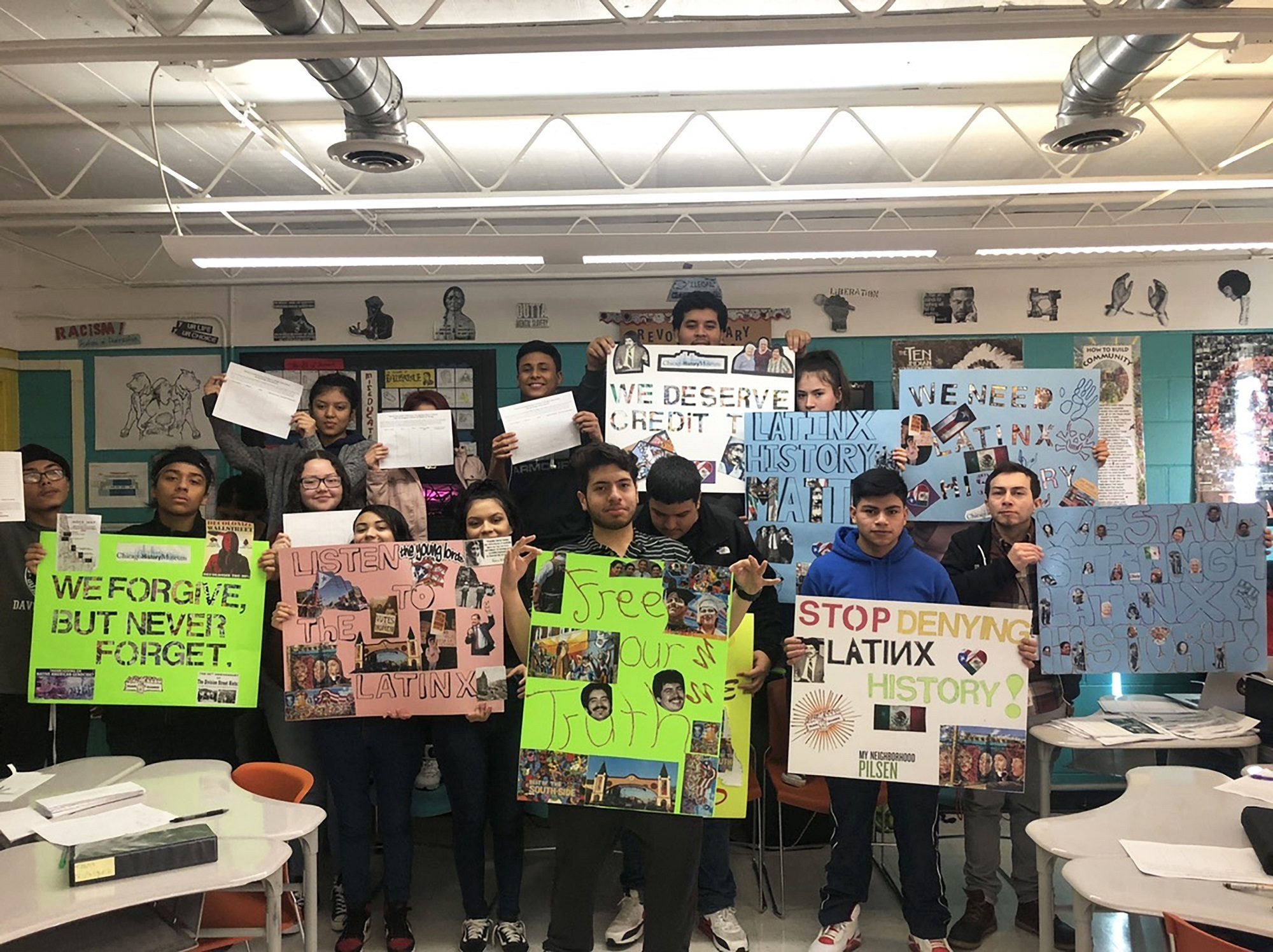

Sparked by a protest in 2019 led by students from the Rudy Lozano Leadership Academy / Instituto Justice and Leadership Academy (IJLA), “Aquí en Chicago” is an upcoming exhibition at the Chicago History Museum (CHM) on the Latino/a/x resistance to white supremacy and colonialism in Chicago over the last 100+ years. “Aquí en Chicago” is a community-driven initiative that shares the diverse historical narratives of Latino/a/x people and is only one part of the museum’s effort to redress a long history of omitting Chicago’s communities of color from its central narrative.

To honor students from IJLA who started this initiative, a paid summer internship program for Latino/a/x high school aged youth has become the cornerstone of “Aquí en Chicago.” A primary goal of the program is to increase youth involvement in the City’s history and CHM is inviting youth all over Chicago to apply.

CHM Curator of Civic Engagement & Social Justice Elena Gonzales said, “Thanks to Bank of America, for supporting the preparation for ‘Aquí en Chicago.’ Time and again, partners and community members have shared how vital they feel it is for the Museum to build its inclusiveness and representation of the Latino/a/x community in our city, and Bank of America is helping us with this crucial work.”

Starting in Spring 2023, interested students can apply to the project and become paid interns who will learn about curation and research skills, how to record community histories as well as plan public programs. Additionally, they will set personal achievement goals during their internship and learn from a cross-section of museum professionals. Their work will culminate in the 2025 exhibition which will explore the diverse experiences of Chicago’s Latino/a/x communities.

This work is made possible through a Bank of America Chicago Market grant. Through direct action and investment, Bank of America is focused on creating opportunities in the areas of basic needs, education and workforce development. These grants are aligned with Bank of America’s five-year, $1.25 billion commitment to help advance racial equality and social justice through a focus on health, jobs and reskilling, affordable housing and small businesses.

###

ABOUT BANK OF AMERICA

Bank of America Environmental, Social and Governance

At Bank of America (NYSE: BAC), we’re guided by a common purpose to help make financial lives better, through the power of every connection. We’re delivering on this through responsible growth with a focus on our environmental, social and governance (ESG) leadership. ESG is embedded across our eight lines of business and reflects how we help fuel the global economy, build trust and credibility, and represent a company that people want to work for, invest in and do business with. It’s demonstrated in the inclusive and supportive workplace we create for our employees, the responsible products and services we offer our clients, and the impact we make around the world in helping local economies thrive. An important part of this work is forming strong partnerships with nonprofits and advocacy groups, such as community, consumer and environmental organizations, to bring together our collective networks and expertise to achieve greater impact. Learn more at about.bankofamerica.com, and connect with us on Twitter (@BofA_News).

For more Bank of America news, including dividend announcements and other important information, register for email news alerts.

Elena Gonzales joined the Chicago History Museum in spring 2021 as a guest curator and began as the Curator of Civic Engagement and Social Justice in October 2022. In this blog post, she talks about her work at CHM and how she approaches it.

Elena Gonzales. Image credit: Ben Gonzales

What led you to the Chicago History Museum?

The Museum reached out to me in spring of 2021 to ask if I would curate an exhibition about Chicago’s Latino/a/x communities. In particular, the project was a response to the protest by high school students from Instituto Justice and Leadership Academy in 2019.

Photograph by Anton Miglietta, History Teacher, IJLA; Courtesy of IJLA and students / alumni.

I had studied and written about CHM relatively extensively at that point, first for my dissertation and later for my book, Exhibitions for Social Justice. To be totally frank, this research left me a little nervous about undertaking the project because I wasn’t sure if the Museum was ready to make the kinds of changes the students were requesting. I’m excited to say that I think we are on that path now.

Your position is Curator of Civic Engagement and Social Justice. How exactly does one go about curating these things? Especially social justice.

The word “curate” comes from a Latin word, “curare,” meaning “to care for.” My work is about caring for people and their stories as well as caring for our society and how well it works for everyone—caring about our collectivity.

My position works in two directions. On the one hand, I am responsible for understanding and employing the Museum’s collections that address civic engagement and social justice in storytelling through exhibitions. Primarily, this is through the Archives & Manuscripts and Prints & Photographs collections with a secondary focus on the Decorative and Industrial Arts collection. On the other hand, it is my job to look for ways that the institution itself can foster civic engagement and work for social justice.

What does a typical day look like for you?

I do a lot of different things as part of my job! They range from research in a library, archive, or special collection to meetings with community members all over town in different neighborhoods and suburbs. On a given day, I could be meeting with a group of paleteros in Albany Park, a scholar in Pilsen, the Little Village Chamber of Commerce, or a family of bomba artists in Humboldt Park. I might be at the Back of the Yards library or researching steel mills in Calumet. These meetings might be about planning collaborations, collecting or borrowing material, or reaching out to additional communities and organizations. I spend two days a week at the Museum exploring the collections, planning and collaborating with colleagues from across the Museum, writing, and so on.

Elena guest teaching at the University of Texas at El Paso’s Centennial Museum in the Pasos Ajenos: Social Justice and Inequalities in the Borderlands exhibition. Photograph by and courtesy of Daniel Aguilera.

You’re leading the charge in curating the Aquí en Chicago exhibition for the Museum, slated to open in 2025. What has that experience been like for you so far?

So exciting! It’s a daunting job to make something about Latino/a/x communities in the area when that population has been absent from the stories at CHM for so long. That makes it feel like there is a lot of pressure for the exhibition to be many different things to different people. This third of the city is so diverse! However, I’ve received a lot of support, both from colleagues at CHM and from Latino/a/x folks of many different backgrounds. We need to keep a focus on the young folks who brought us into this project in the first place. When we center their story—as this exhibition will—the landscape around their story becomes clear. That’s how we got to the focus on resistance against white supremacy and colonialism (in all its many forms). So far, working on this project has been a wonderful experience. It’s a tremendous challenge and so rewarding. One partner at a community-based organization said the nicest thing when she learned we were planning the exhibition for fall 2025. I’m used to people wanting to hear more about why the timeline is so long (trust building and relationship building take time), but what she said was “I feel so safe.” Her words have stayed with me, and I hope to live up to them.

Is there a particular artifact or collection in the Museum that is your favorite or one that has had the most impact in your work so far?

Though it is by no means my favorite, there is an object that I’m kind of obsessed with. It’s offensive not only in its expansionist, colonial stance but also in its butchery of Spanish. It opens a window onto a whole part of the story landscape that is crucial and difficult to access and highlight. The object is called “The American Hen.”

Milk glass bowl with lid, c. 1898. 1973.23a-b. Photograph by Elena Gonzales.

It’s a mass-produced covered dish of milk glass about the size of a butter dish—though it may have been used to hold a condiment such as mustard. Westmoreland Specialty Co. produced it around 1898, likely as a novelty. This was a time when the US doing significant colonization in Latin America. In 1898, the US took over Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam, and Cuba—though the US was unable to retain control of the last. “The American Hen” takes the form of a (presumably American) eagle sitting on its nest, its wings outstretched around three eggs labeled “Porto Rica [sic],” “Cuba,” and “Philippines.” It is one of the few objects I’ve found so far that will allow us to have the necessary conversation in the gallery about how US military and economic intervention in virtually every Latin American country has directly influenced the Latino/a/x landscape we live with today in Chicago.

Additional Resources

- Learn more about Elena

- Follow her on Twitter @curatoriologist

From sundown on Tuesday, October 25, through sundown on Thursday, October 27, followers of the Baha’i faith will be celebrating important Twin Holidays: the birth of the Báb (Arabic: the Gate) and birth of Bahá’u’lláh (Arabic: Glory of God), its two foundational figures. In recognition, we look to the Chicago History Museum’s collection of pamphlets representing moments in the community’s history as it established physical presence in the Chicagoland area.

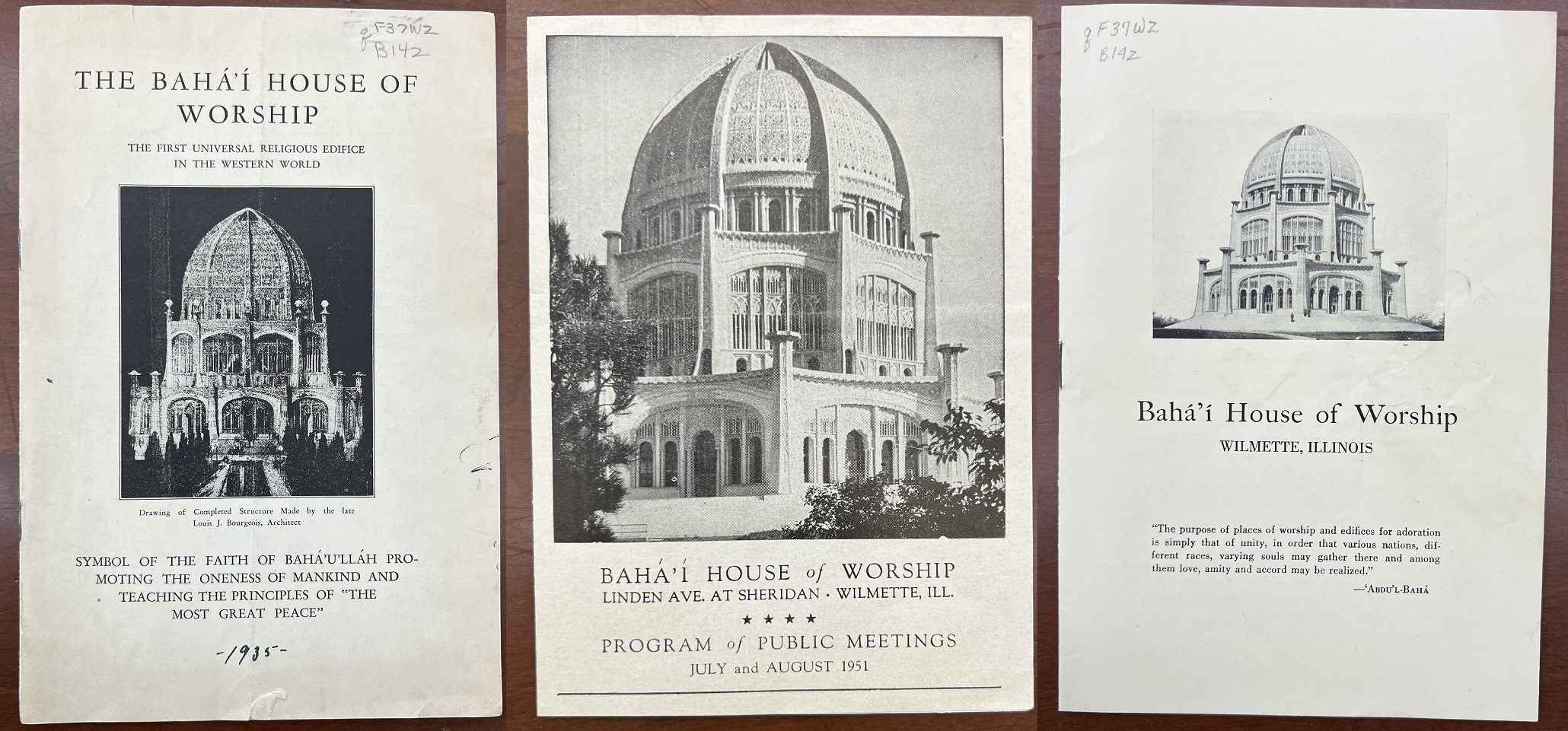

A selection of pamphlets from CHM’s Abakanowicz Research Center.

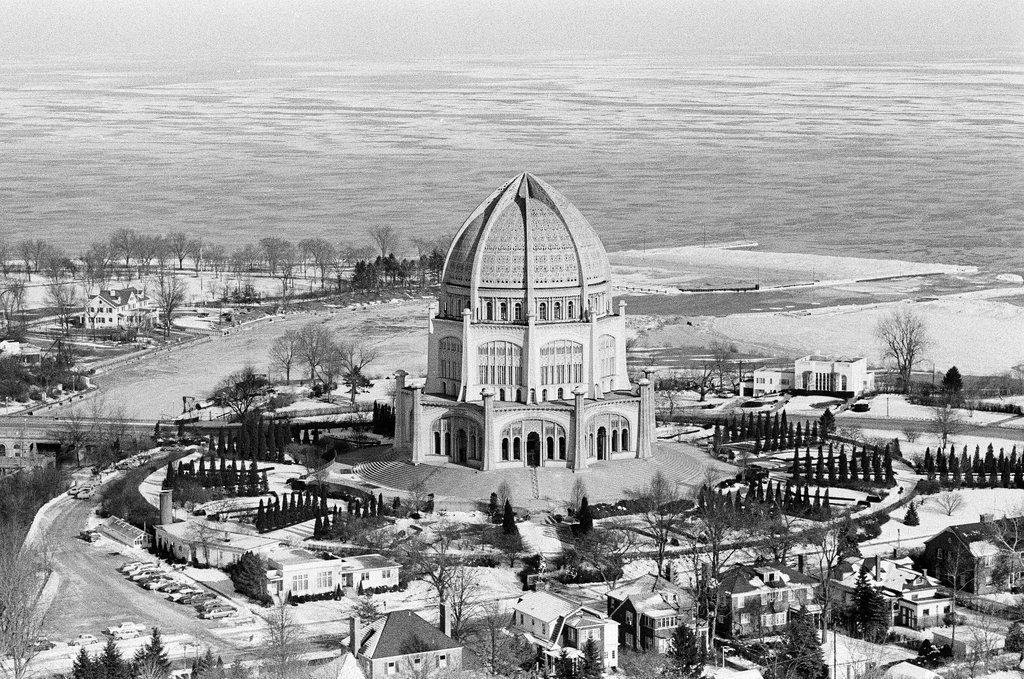

The Mashriqu’l-Adhkár (Arabic: The Dawning Place of Praise) in Wilmette, Illinois, is the second Baha’i House of Worship in the world to be built and is the oldest remaining one. The structure embodies the teachings of Bahá’u’lláh as an expression of humanity’s oneness. Its foundation stone was laid in 1912 by ‘Abdu’l-Baha (the son of Bahá’u’lláh), and the completed building was dedicated in 1953.

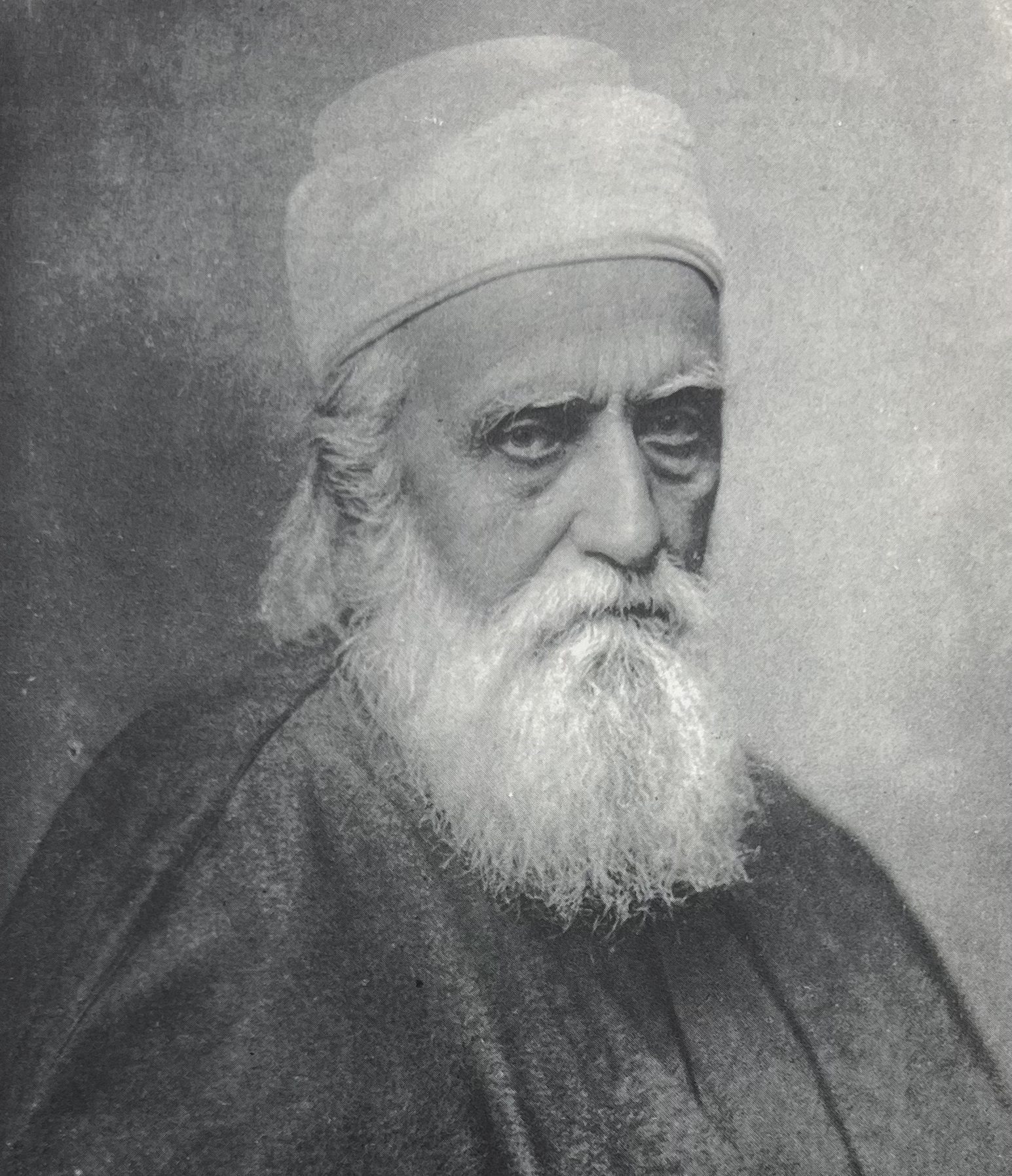

Portrait of ‘Abdu’l-Baha, oldest son of Baha’u’llah, in The Bahà’ì Faith: Dawn of a New Day by Jessyca Russell Gaver

The pamphlets discuss the Baha’i faith’s foundations and significant historical moments, grounded in the Birth of Bahá’u’lláh in 1817 and Birth of the Báb in 1819 in Iran and extending through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Other events described include the founders’ experiences of pilgrimage and exile, the recognition of the Baha’i faith at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893, and significant inaugural events of the Chicago Baha’i community. They also discuss the long and storied process of conceptualizing, designing, building, and celebrating a meaningful place of worship that represents community beliefs in architecture.

Aerial view of the Baha’i House of Worship with Wilmette Harbor and Lake Michigan behind it, January 6, 1971. ST-20001475-0001, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The temple in 2022. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman.

The building’s architect, Louis Bourgeois, made eclectic reference to world architecture in his design—borrowing from Egyptian, Roman, Byzantine, Renaissance, and Islamic traditions—to manifest humanity’s combined efforts to worship the divine through built form. The number nine is repeated in the number of sides, entrances, and gardens at the House of Worship, symbolizing perfection and completion. Its intricate, decorative exterior appears as carved stone but is in fact achieved through a unique mixture of white Portland concrete and white quartz, which creates a glimmering effect and gave rise to its nickname as the “Temple of Light and Unity.”

Detail of inscription above the doorway. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman.

Decorations include symbols of world religious traditions, including hooked crosses associated with Buddhism and Hindusim, Judaism’s Star of David, Christian crosses, the moon and crescent of Islam, and the nine-pointed star of Baha’i. Nine utterances of Bahá’u’lláh are above entrances and nine are within interior alcoves. Each gives testament to Baha’i beliefs, emphasizing Bahá’l’ulláh’s teachings of universal peace, including one that reads, “The earth is but one country; and mankind its citizens.”

Additional Resource

- See our archival materials about the Baha’i faith at the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit

This ghostly image was taken at the Electric Theater night club at 4812 North Clark St., Chicago, April 5, 1968. ST-10003431-0024, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM

Chicagoland has a lot of ghost stories, but none are as well-known as the infamous Resurrection Mary, the hitchhiking ghost who haunts the roadsides of Archer Avenue. Mary has different origins, depending on who’s telling the story, but the most shared narratives put her untimely death sometime in the late 1920s to early 1930s, when she was either a victim of a fatal car crash on the way to a night of dancing or the unfortunate victim of a hit-and-run accident while she was walking home in the rain.

While this was worn as a wedding dress, it demonstrates 1930s style; silk satin and lace with silk flowers, 1930. CHM, ICHi-054652

Most documented reports of Mary describe her as a young, fashionable blonde woman no older than mid-twenties, wearing a white ball gown, accessories, and hairstyle to match. As the story goes, she typically manifests as a lonely guest at a dance hall, and after a night of dancing, she asks for a ride back home, slipping into the backseat and guiding her driver for the night (usually a man) up Archer Avenue. But by the time the car reaches a local cemetery, Mary vanishes without a trace, leaving nothing more than her ghostly memory.

This hair stylist’s mannequin (c. 1935) shows a beehive style that Mary may have worn. CHM, ICHi-067232

Mary is supposedly buried at Resurrection Cemetery, in Justice, Illinois, about a 30-minute drive southwest of Chicago. This burial ground gives Mary her stomping grounds, as well as her iconic name. She usually sticks to this stretch of road on Archer Avenue, between the cemetery and what was once the Oh Henry Ballroom (later renamed the Willowbrook Ballroom) in Willow Springs. Over the years, several researchers have tried to determine the exact identity of Mary, but no answer has proved conclusive.

View of various metallic women’s pumps c. 1930.

Resurrection Mary’s fame has gone beyond Chicagoland. Her hitchhiking ghost has had a number of ballads written about her, along with a few B-list horror movies (all named after her), and even a couple segments on Unsolved Mysteries. On a more local level (and for those thirsty for a good drink), Chet’s Melody Lounge on Archer Avenue in Justice, right across the street from Resurrection cemetery, has a tradition for Mary. Every Sunday, they serve a Bloody Mary at the end of the bar for her. To date, Mary hasn’t shown up to claim the drink—maybe she’s waiting for the right person to accompany her and then give her a ride back home.

The trope of the hitchhiking ghost is a common one not only in the United States, but across the world. Stories of phantom hitchhikers are part of the common folklore in both urban and rural areas, with stories similar to Mary’s showing up in South Carolina’s infamous Walhalla Hitchhiker, the phantom hitchhiker of Bedfordshire in Great Britain, and in Quezon City in the Philippines, where she is known as the White Lady. These urban legends often serve as cautionary tales, reminding those out in the late hours of the night that not everything may be what it seems, and that sometimes it’s just best to keep on driving.

You can read more about Mary and other Chicago folk stories in the Encyclopedia of Chicago.

In our latest blog post, CHM costume collection manager Jessica Pushor talks about the fascinating life of Louis “Scotty” Piper, his career as a tailor, and his generous donations to the Chicago History Museum. Piper is one of the designers featured in Treasured Ten: Selections from the Costume Collection, which runs through January 16, 2023.

A native of New Orleans, Louis Vernon “Scotty” Piper moved to Chicago in 1916. Three years later he found himself in the middle of the 1919 Race Riot. Piper fled the city, leading his family to believe he was killed. According to Piper, he briefly worked for a circus, quit when he reached Minneapolis, began performing the Charleston in dance competitions, and returned to Chicago in 1922.

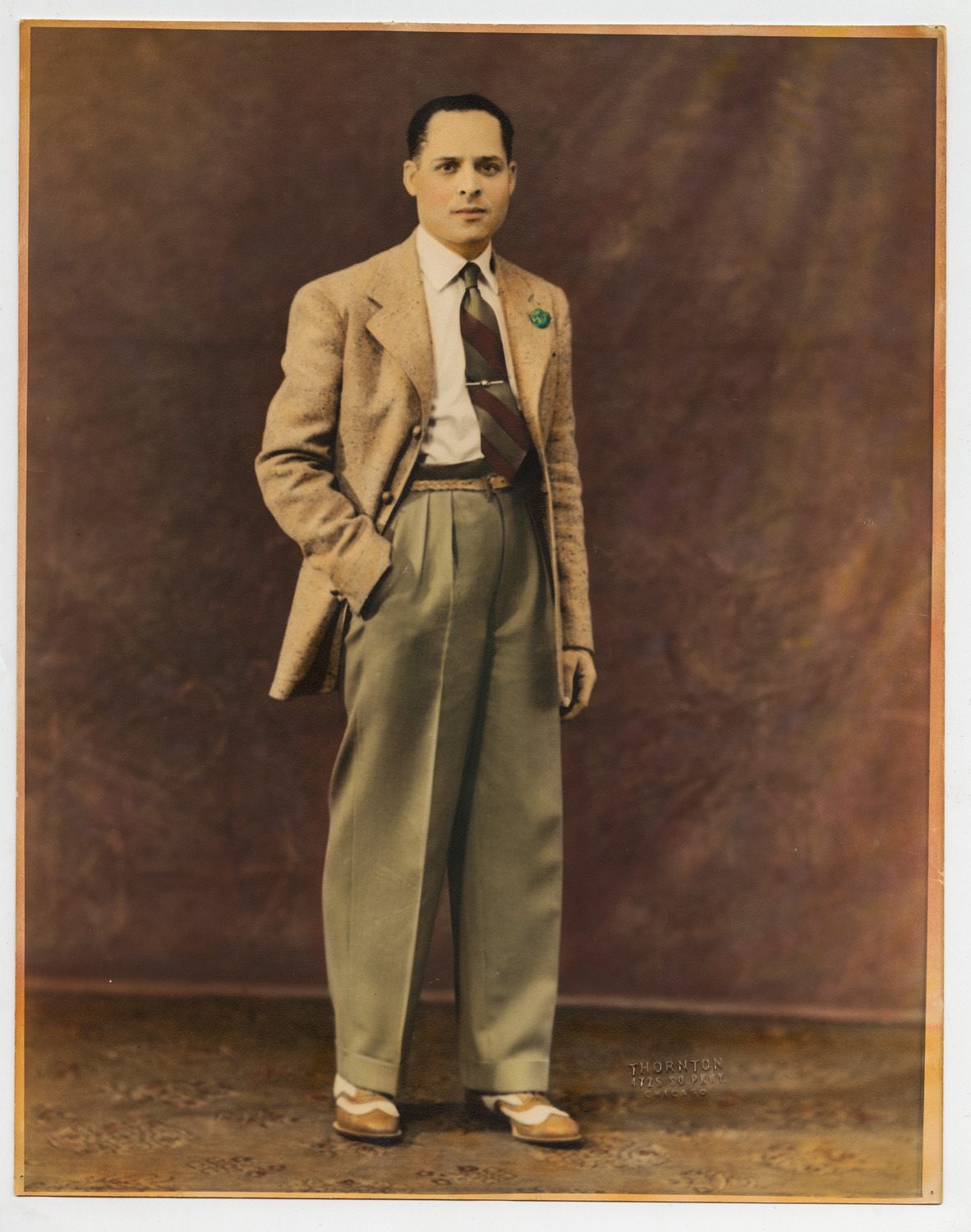

Undated, hand-colored portrait of Scotty Piper in a suit. CHM, ICHi-174414

Later that year, Piper began working for Lew Fox, a tailor known for outfitting entertainers and gangsters. He learned to sew and began to establish his own clientele among local performers. In 1925, Piper opened his own tailoring business on 47th Street in Bronzeville, attracting both local and nationally known Black entertainers. For more than five decades, he created suits for prominent figures such as athlete Jack Johnson and entertainers including Duke Ellington, Cab Calloway, Count Basie, and Louis Armstrong. Piper’s shop was also a popular place for young Black men to purchase graduation suits, which he made for Harold Washington, Nat “King” Cole, Sam Cooke, and Lou Rawls, among others. As Piper’s career progressed, collecting photographs of his customers and other celebrities, as well as local clubs, became a hobby for him.

Piper (right) measures a man for a suit as two women in dresses stand and watch, c. 1940s-1950s. CHM, ICHi-174413

In 1975, Chicago Tribune reporter Clarence Page interviewed Piper about his 50 years in business on 47th Street and how the neighborhood had changed during that time span. The article also mentioned his collection of photographs and scrapbooks of Black entertainers and musicians that Piper had dressed and the clubs and theaters on 47th Street he visited, many of which had become legends in time. Thanks to the Tribune’s wide distribution, many people outside of Bronzeville and Chicago were introduced to Piper.

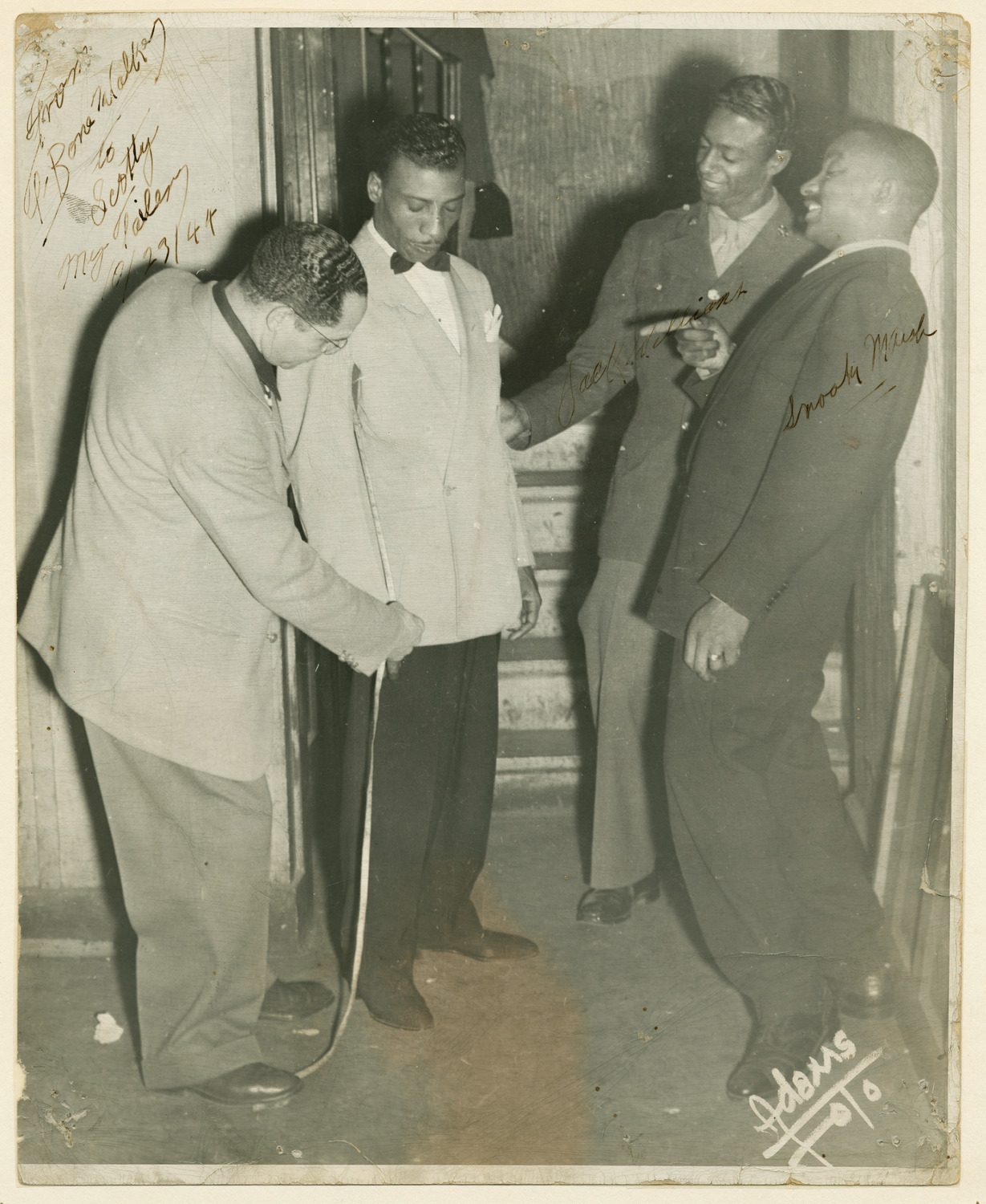

Autographed photograph of Piper measuring T-Bone Walker as Jack Williams and Snooky Marsh watch, 1944. CHM, ICHi-036108

An undated, signed headshot of Rhythm Willie. The inscription reads: “To my tailor Scotty Piper. Rhythm Willie.” CHM, ICHi-174228

John Triss, a graphics curator for what was then the Chicago Historical Society, saw the article and wrote to Piper hoping to expand “our very incomplete photo records of Chicago’s black people.” Piper agreed and donated about 300 photographs (c. 1920–69), mainly of Black entertainers and celebrities, but also some personal photographs of Piper, his family, and friends that reflect his involvement with social, church, and civic affairs. He also included miscellaneous letters from various African American organizations soliciting his aid or participation or thanking him for his contributions (1954–68). Finally, Piper also donated some men’s suits from his shop and from his own closet to the CHM costume collection. Thanks to his generous donations, as he told Clarence Page in 1975, “the old 47th Street can live forever.”

Additional Resources

- Peruse Scotty Piper’s archival collections in the Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit

- See a selection of digitized images related to Scotty Piper

This blog post has been adapted from an essay by CHM intern Bella Santos, based on her work in the summer of 2022 around the printmaker Carlos Cortéz and the work of student activists at the Chicago History Museum.

In September 2019, Anton Miglietta, a history teacher at Instituto Justice and Leadership Academy (ILJA) in Pilsen, brought his class—learning about marginalized communities in Chicago—to the Chicago History Museum. On their trip, the students were met with very few artifacts or stories relating to Latino communities in the Museum. Soon after, the students organized protests and a social media campaign to express their anger about the lack of Latino/a/x history within CHM. The Museum held a meeting with the students and agreed on broadening its content to reflect Chicago’s population and creating an exhibition showcasing Latino culture.

When CHM brought me on as an intern, a main focus was how to appropriately represent an unrepresented community in the Museum. Historical erasure of minorities is a problem within archival institutions; CHM is no exception. Latinos make up 29% of Chicago’s population—a significant portion of the city. A city museum should reflect that city’s changing demographics—past and present. One way to do this is to use recent events to connect the stories of the past to many populations. Latinos are one of these groups.

Carlos Alfredo Koyokuikatl Cortéz (1923–2005), a Latino artist from Pilsen, is one person from a long list of underrepresented Latino activists and artists in Chicago’s history. Cortéz’s contributions to his community in Pilsen, the Chicagoland area, and the entire country is an example of someone who, like the students of IJLA, used his voice to spread a message of equality.

Carlos Alfredo Koyokuikatl Cortéz was born in Milwaukee on August 13, 1923. He grew up in a politically active family. His father, Alfred E. Cortéz, was a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) labor union, and his mother, Augusta Cortéz, was a member of the Socialist Party of America. Carlos grew up in Milwaukee, one of the epicenters of labor, racial, and civil rights debates in the 1960s and 1970s and then moved to Chicago and continued the family enterprise of political activism.

Cortéz was among the many men drafted into the army after the bombing of Pearl Harbor (1941), but he opposed the impending fights. Rebecca Meyers, permanent collection curator at the National Museum of Mexican Art, described his opposition to the draft as being against the “common man fighting the common man on foreign soil.” As a conscientious objector, Cortéz spent 18 months in prison.

The façade of the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum, which became known as the National Museum of Mexican Art in 2006. Image courtesy of Carlos Tortolero

The opening of the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum in 1987. Chicago mayor Harold Washington is in the right foreground with the red tie. Image courtesy of Carlos Tortolero

Cortéz’s political views translated into his artwork. He was inspired by José Guadalupe Posada, a popular Mexican lithographer famous for his pieces featuring political and social problems. Cortéz worked with fellow artist Leopoldo Mendez to create prints. In my interview with Meyers, she discusses the works of both artists and says,

They never destroyed the blocks that produced their prints. It was a way for Carlos to spread the word, to spread his artwork to as many people as he could. They were never interested in selling the prints or the blocks, it was all about the message.

Cortéz’s printing press was his form of mass, social, and fast media. Making his artworks readily available for anyone was his way of spreading his messages and increasing awareness about police brutality, political events, and personal reactions to global events.

Cortéz’s printing press. Photograph by CHM staff.

Among the events Cortéz responded to through his “mass media” art were a print titled “We Serve and Protect,” depicting police brutality, to bring awareness to the injustices that minority communities experienced, which he printed and distributed at the 1968 protests of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Carlos Cortéz, La lucha contínua / The Struggle Continues, 1986, woodcut, N.N., 17 5/8” x 21 5/8” (paper size), National Museum of Mexican Art Permanent Collection 1997.1, Gift of Carlos Cortéz, photo credit: Kathleen Culbert-Aguilar

Another of his recognizable pieces, titled “La Lucha Continua” (“The Struggle Continues”), reflects his experiences being a part of the IWW, and the case of five miners who were killed during the 1927 Columbine mine protests in Colorado. The protests started in response to and in solidarity with the wrongfully accused and murdered Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, with miners from the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company striking to improve the wages and working conditions of the workers. In 1989—62 years later—Cortéz went to the graves as a representative for the IWW to scatter the ashes of the last deceased miner, and he created “La Lucha Continua” in response to the injustices the laborers experienced. Workers’ struggles and Cortéz’s work convey a message of equality that is shared with other acts of protest.

Jair Urier Ramirez, a student at IJLA during the 2019 protest of CHM described his experiences to me. One notable thing he said was this,

I have calluses on my hands and bags under my eyes, you know? These are things that I would like to tell, my story, you know? And as someone who works with brown people every day, I think that’s something important to us. Why? Because we have different stories, and I think that was the ultimate essence of our project. And I say essence because that’s really how it was. Let us tell our stories and don’t stereotype us.

Ramirez is right that the upcoming Latino/a/x exhibition is including Latino communities and giving the right recognition to the right people. From my perspective, as a Latina, throughout this whole internship I saw how meaningful their protest was and how powerful it was to see people unite for a cause that adults had not taken action on. There is no singular way to solve societal dilemmas. We can only start by advocating for one another, and I do think this internship, as new as it is, is a great step towards change.

An undated photograph of NMMA president Carlos Tortolero touring the museum with then Senator Barack Obama.

When I first started, I had no idea what to expect, but as I interviewed more people and asked questions, it became clear how unifying this project is. It was enlightening to see how my research connected to Carlos Cortéz and his accomplishments with his artwork, the students with their protest, and me with my small contribution to this exhibition.

Further Reading

- Carlos Alfred Cortéz in the Chicago Latino Artchive, Inter-University Program for Latino Research

- Carlos Alfred Cortéz at the National Museum of Mexican Art

- Chicago: Law and Disorder

- Crystal-Gazing the Amber Fluid and Other Wobbly Poems by Carlos Cortéz

This blog post has been adapted from an essay by CHM intern Megha Khemka, based on her work in the summer of 2022 focused on Chicago’s history with immigration.

Whatever your current picture of undocumented individuals, it’s probably incomplete. I know mine was. Immigration was a topic I thought I knew well; my parents were the first in their families to live outside of India. Yet the news I was reading around 2016—asylum requests systematically denied, detention centers lacking essential resources—was worlds away from anything I knew. Over the next few years, the material I saw grew denser and more polarized. It was only when I began researching the topic of sanctuary with the Chicago History Museum that I began to ask questions of my hometown and learned that Chicago has a lot of answers. To demonstrate, we’ll begin with a story that you perhaps have heard, the story of Elvira Arellano.

Arellano was born in Michoacán, Mexico, in 1975. She was 22 when she came to the United States. Thanks to Chicago’s sanctuary laws, she was able to build a life here with her US-born son, Saul, despite not having legal status. In the aftermath of 9/11, however, Islamophobia and xenophobia led public sentiment to associate immigrants with terrorists. After the passing of the USA PATRIOT Act, national authorities conducted extensive sweeps of all federal buildings. They arrested Arellano, who worked at O’Hare International Airport, and ordered her to appear before an immigration court. When she pointed out that deportation would separate her from her four-year-old, a US citizen, federal authorities responded that the only way she could be with her son was to uproot him to Mexico. It was a story that brought to light for many the United States’ citizenship and immigration policies.

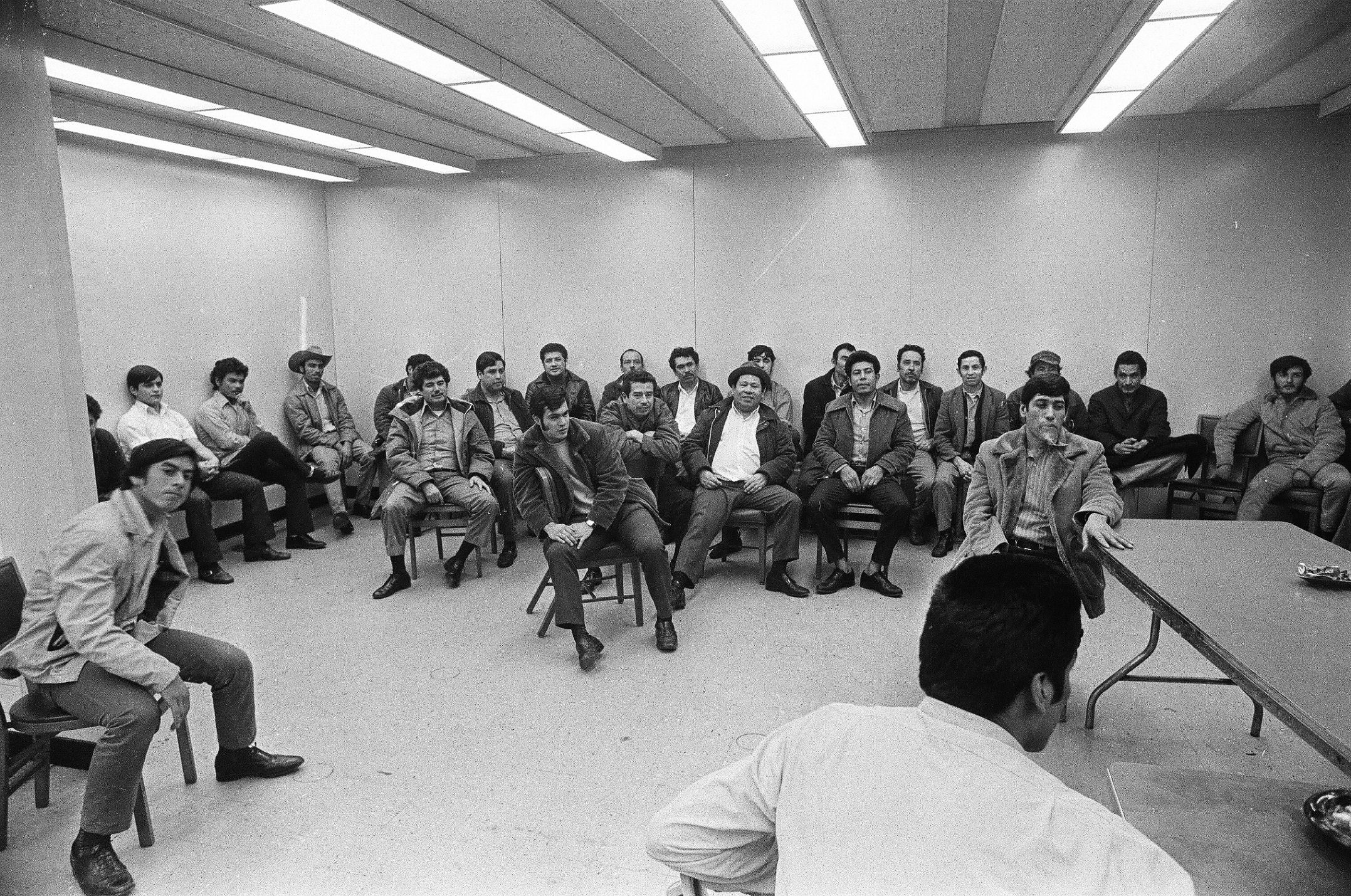

Undocumented immigrants of Central and South American descent sit in a room after being seized in a raid, Chicago, December 13, 1971. ST-10103912-0005, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The sanctuary movement in Chicago arose in the aftermath of civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala, funded in part by the US government, during which nearly one million refugees sought asylum in the United States between 1980 and 1991. Among those who had been killed in El Salvador were four US missionaries, and they became the face of a new organization: the Chicago Religious Task Force for Central America. It advocated for federal foreign policy changes toward Central America and encouraged domestic communities to host Central American refugees. In Chicago, they created a framework that connected undocumented immigrants with churches that were willing to provide them sanctuary.

A group of people gather in the Federal Building plaza to protest US aid to El Salvador’s military government during the Salvadoran Civil War, Chicago, February 7, 1982. ST-30002672-0027, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Bob Black

The idea quickly took hold, and in 1982, the congregation of Chicago’s Wellington Avenue Church voted to become America’s second sanctuary church. Over the next decade, 20 religious institutions in and around Chicago became sanctuaries, housing undocumented refugees and providing them with platforms—for example, venues for public press conferences and Bible study discussions—to make their stories heard. Participants were Christian, Quaker, and Jewish, creating a vast network of unsanctioned support.

A group of people gather in the Federal Building plaza to protest US aid to El Salvador’s military government during the Salvadoran Civil War, Chicago, February 7, 1982.ST-30002672-0042, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM; photograph by Bob Black

In my research, I discovered the impact of hundreds of diverse Chicagoans united in their belief. Even those who were hesitant to speak out enabled more vocal voices through their support. Adriana Portillo-Bartow’s two daughters were kidnapped in Guatemala, and after escaping civil conflict by moving to Chicago, she tirelessly campaigned the government, Catholic Church, and media to find her girls. Similarly, diverse coalitions came together in the election of Chicago’s first African American mayor, Harold Washington, who codified social support into law with Executive Order 85-1, written to “assure that all residents of the City of Chicago, regardless of nationality or citizenship, shall have fair and equal access to municipal benefits, opportunities and service.” This has formed the basis for Chicago’s legal protection of undocumented immigrants ever since.

However, a series of cases known as the Sanctuary Trials highlighted the lack of such legal protection on a federal scale. In 1986, the Justice Department indicted 16 individuals on 71 counts of conspiracy and of aiding “illegal aliens to enter the United States by shielding, harboring and transporting them.” Though the defendants argued that providing refuge was an expression of religious belief and therefore protected by the First Amendment, this argument was struck down by courts. Undocumented immigrants taking refuge in a religious institution are not immune from deportation. The protection that a sanctuary church offers is entirely social, based on the reluctance of any authority to order a raid on a religious building. Nevertheless, public support had power in the Sanctuary Trials, leading Congress to grant asylum to most of the individuals involved, illustrating the power of media narratives and community protest.

With that in mind, we return to Elvira Arellano, who until 2002 had been living quietly in America, trying to avoid deportation. After she was arrested, Arellano made a pivotal decision: she took refuge in Humboldt Park’s Adalberto United Methodist Church in 2006 on the date of her immigration hearing. She lived there for more than a year, eventually being deported while traveling to speak at a Los Angeles church. Her son remained at his home in the US, while Arellano continued to advocate tirelessly from Mexico. In March 2014, she presented herself to US Border Patrol officials at the San Diego border to request asylum.

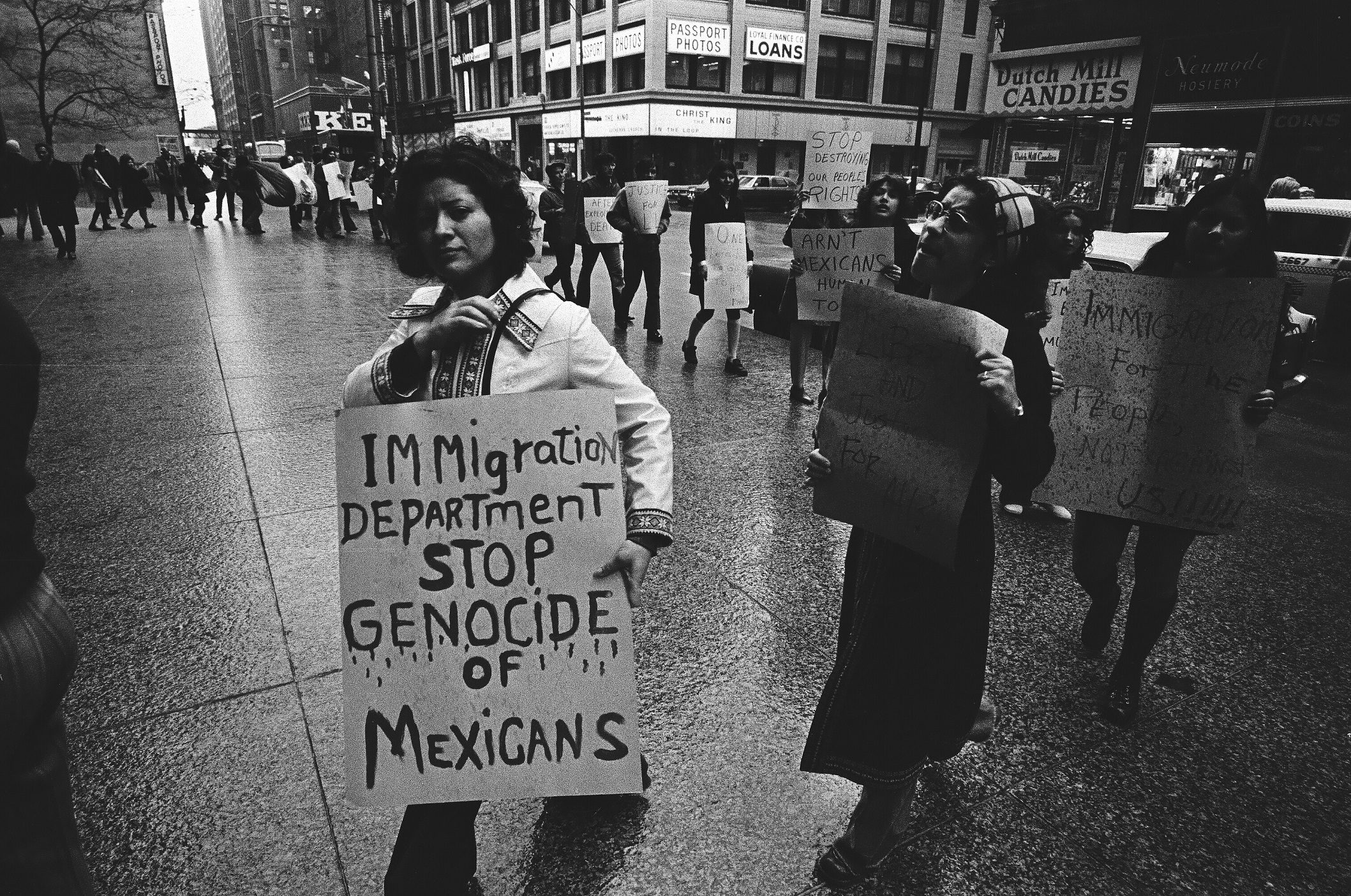

Protest at the Federal Building, 230 South Dearborn Street, over shooting of undocumented Mexican immigrant, Chicago, November 10, 1972. ST-14002237-0004, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Arellano’s story quickly began to gain national attention; as a powerful mother figure fighting to be with her American son, she was the perfect face of a new Sanctuary Movement. And it worked. Legal change at all levels of government followed during this time, including in Cook County, which passed an ordinance refusing to fill federal detainer requests for those suspected of being in America without a visa. However, the national buzz around Arellano’s story created a narrowly defined narrative of undocumented individuals in America that tied their right to stay in the country with the fact that they grew up here or had a child who did.

For instance, the Obama administration’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals policy allows undocumented individuals who came to the US as children to apply for deportation deferrals every two years. While the executive order benefited thousands of Chicagoans, Arellano herself argued that it didn’t go nearly far enough, only providing temporary relief for a very select group of people.

After the sustained efforts of a diverse coalition of Chicagoans, Chicago today is has one of the most comprehensive legal systems in place to support undocumented immigrants. The city’s population fought to preserve their deeply-held values of sanctuary even under pushback from Illinois governor Bruce Rauner, and Chicago’s lawsuit against the Department of Justice in 2017 is what has ensured that sanctuary cities all over the country are legally entitled to federal funding.

Yet, Chicago’s stories also remind us that sympathetic legislation does not mean the work for asylum seeker and undocumented individuals is done.