For St. Patrick’s Day, CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman looks at Old St. Patrick’s Church as a monument to Chicago’s longstanding Irish community presence and how its stained glass windows reflect Irish American identity.

Old St. Patrick’s Church, also known as St. Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church, 2024. Photograph by Rebekah Coffman

St. Patrick’s Day in Chicago means the city is filled with Irish heritage on display. While Chicago may be best known for its green river, festive parades, and raucous pub crawls, Old St. Patrick’s Church in the West Loop neighborhood is a monument to Chicago’s longstanding Irish community presence.

Old St. Patrick’s Church, August 4, 1975. ST-19042225-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Named for the patron paint of Ireland, Old St. Patrick’s Church was founded on Easter 1846 by Irish bishop William Quarter as the first English-speaking Catholic church in Chicago. Initially in a humbler wooden building at the intersection of Randolph and Desplaines Streets, the cornerstone was laid for a new brick building on May 23, 1853. Completed in 1856, the church would be one of a handful of buildings to survive the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, making it the oldest public building in Chicago today.

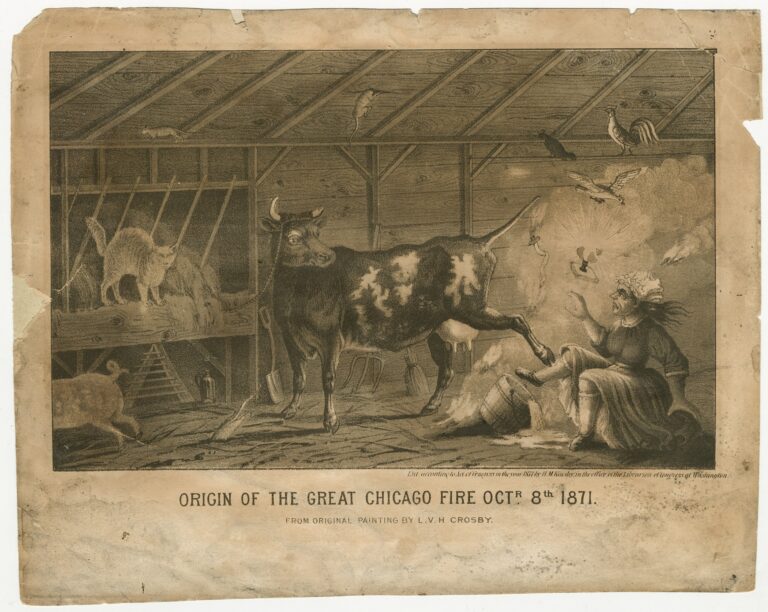

Cartoon by L. V. H. Crosby depicting “the Origin of the Great Chicago Fire” featuring a stereotyped image of Catherine O’Leary and her cow in a barn. CHM, ICHi-002945

Irish immigration to Chicago began in the 1830s and grew exponentially following serial potato crop failures beginning in 1845. By 1860, Chicago had the fourth largest Irish community in the country. Religious divides present in Ireland found their way to the Irish immigrants’ new home, with Protestants separating themselves from Catholics by both religious identity and social and economic class. Soon, Irishness in Chicago became publicly synonymous with Catholic and working-class or poor. Prejudice against Irish immigrants led to pervasive social stereotyping during this time, including the legendary story of Mrs. O’Leary and her cow as the source of the Great Chicago Fire.

View of the Irish Village at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition with a banner reading “Cead Mile Failte” meaning “Welcome.” CHM, ICHi-022941

Two decades later, Irish presence and identity were again on display as part of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. Two idealized Irish villages were included in the ethnographic displays along the Midway Plaisance, where visitors could see glimpses of the romanticized “everyday life” of the rural Irish. The setting included thatched cottages, a reproduced Muckrass Abbey, a recreation of Blarney Castle (complete with a place to kiss a piece of the Blarney Stone), and various cultural displays, including Celtic arts and crafts. This and other romanticized visions of an Irish homeland would go on to influence artists and designers looking for inspiration amidst the chaotic progress of the Industrial Revolution, including a young man by the name of Thomas O’Shaughnessy. He would become a cornerstone in defining Chicago’s flavor of the Celtic Revival Style.

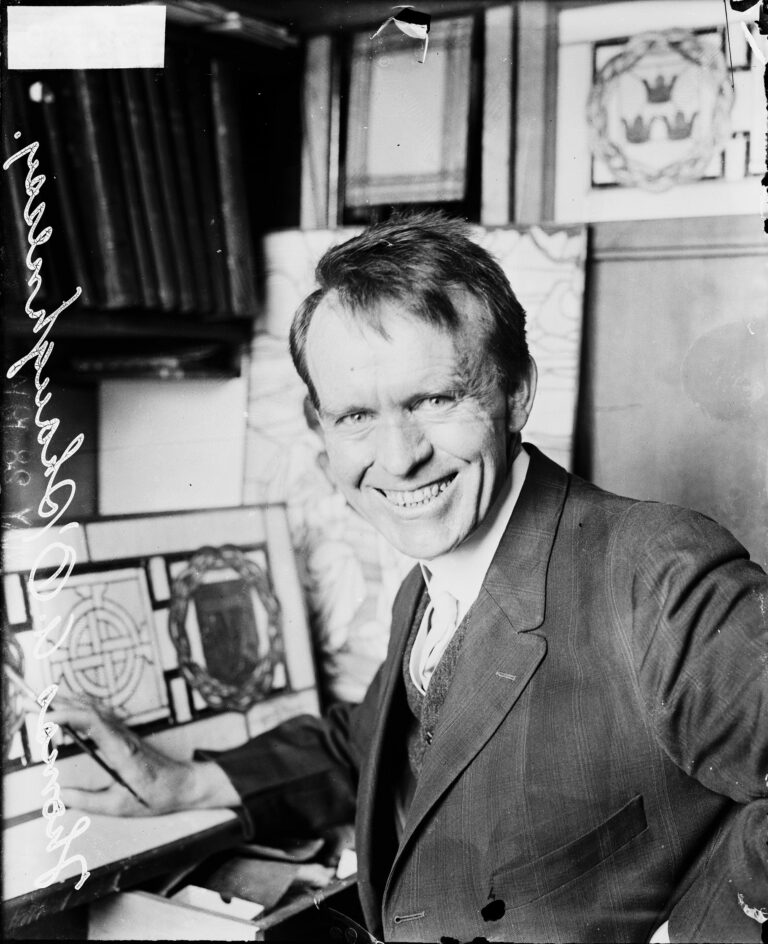

Artist Thomas O’Shaughnessy with a stained-glass tile featuring a Celtic design, May 16, 1914. DN-0062780, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Born in 1870 and originally from Missouri, O’Shaughnessy studied stained glass at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, learning from local stained glass legend Louis Millet. Millet is perhaps best known for designing nature-inspired windows for buildings such as Louis Sullivan’s Auditorium Building and, with partner George Healy, the dome in the Grand Army of the Republic Hall at what is now the Chicago Cultural Center. O’Shaughnessy would later take the techniques he learned and apply them to a new visual language steeped in Irish heritage.

Artist Thomas O’Shaughnessy working on a piece of stained glass art, 1920. DN-0072728, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

As noted above, O’Shaughnessy became deeply inspired by Celtic design, first encountering it at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. In 1905–6, after he finished his formal studies and started work as an illustrator for the Chicago Daily News, O’Shaughnessy traveled in Europe to gain wider artistic inspiration.

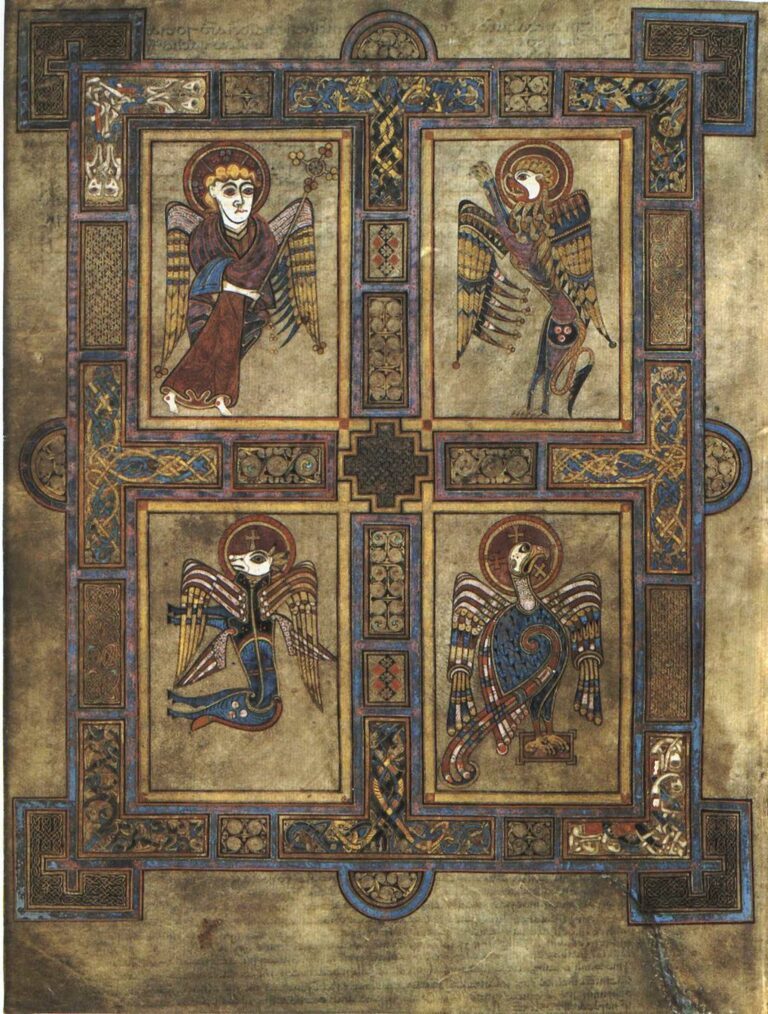

Pages from the Book of Kells, 9th century, Trinity College Dublin.

While in Ireland, he was particularly drawn to the themes and pattern work he saw in the Book of Kells, a 9th-century illuminated manuscript containing the four books of the Christian gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). The Book of Kells is widely known for its impressive ornamentation and pages of illustration that infuse Celtic imagery and design with the Latin text of Christian scripture. These designs became a major source of inspiration for many artists during the late-19th and early 20th centuries as part of the Celtic Revival, and Celtic designs were documented, replicated, and incorporated in a number of fine and decorative arts.

Stained glass windows at the balcony of St. Patrick’s Church, 2024. Photographs by Rebekah Coffman

O’Shaughnessy brought this influence into his design work for St. Patrick’s Church, creating a distinctive hybrid Irish-meets-American style. He designed and installed fifteen major windows from 1912 to 1922, each incorporating Celtic elements to visually assert Irish American identity through the building’s decoration. Irish-born Chicagoans were at a near-peak in the city until quickly tapering after the Immigration Act of 1924.

St. Patrick’s Day Parade on State Street, Chicago, March 17, 1976. ST-15003202-0105 and ST-15003202-0107, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Irish immigration to Chicago was halted almost completely during the Great Depression until the 1950s, with a final big wave arriving after leaving during Irish unrest of the 1970s–90s. Today, more than 430,000 people in Cook County claim Irish ancestry and organizations like the Irish American Heritage Center in Irving Park continue to share and celebrate Irish presence in the city. While a number of formerly Irish parishes have shifted in use or been lost to demolition, Old St. Patrick’s stands today as a reminder of long-standing community presence.