In Chicago, there are neighborhoods, community areas, and wards, and each term has a distinct meaning. CHM curator of religion and community history Rebekah Coffman explains the differences, why these distinctions exist, and how they change over time, a key theme explored in our upcoming exhibition Aquí en Chicago.

What is a community, and is that the same as a neighborhood? Chicago’s identity as a “city of neighborhoods” implies there would be some way of defining what these neighborhoods are, what that means for Chicagoans living here, and how they create our sense of community. And yet, there are countless ways to think about and draw boundaries around how we could divide and subdivide the city. This could be based on where you live, what businesses you visit, or where your place of work or place of worship is located. It can also be a feeling, somewhere you consider a home, the spaces you walk by every day, the street corners you recognize, where your friends live.

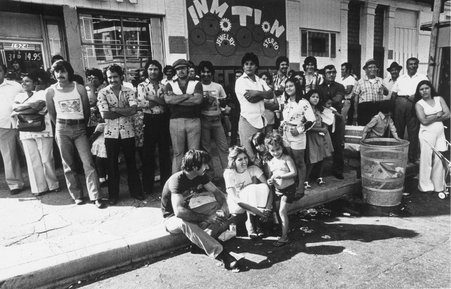

Fiesta del Sol in the Pilsen neighborhood, Chicago, August 1978. CHM, ICHi-031836

When discussing neighborhoods, it is important to think about how there is the idea of a neighborhood, a concept recently re-explored again by the Chicago Neighborhoods Project, and a physical or political boundary used for a specific purpose. In this latter sense, Chicago is often divided in three main ways: neighborhoods, community areas, and wards.

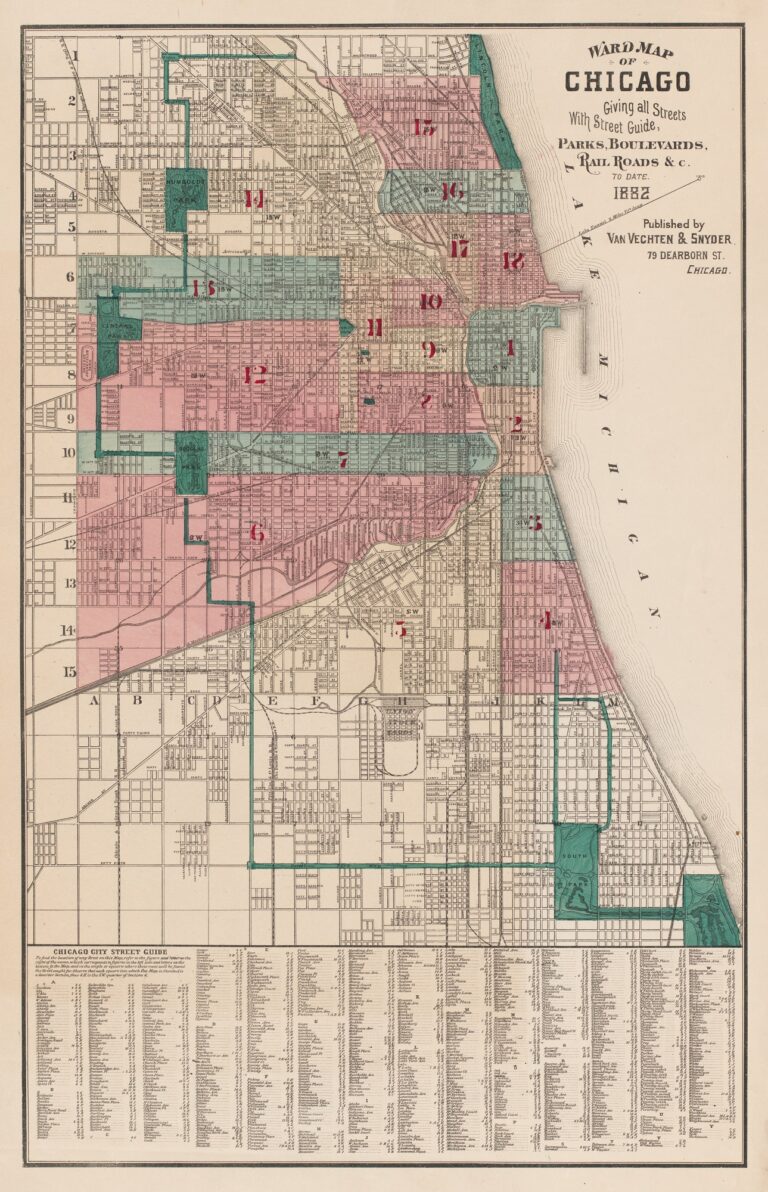

(L) Ward map of the City of Chicago, 1882. CHM, ICHi-092878

(R) Ward map for the City of Chicago, September 19. 1947. CHM, ICHi-173823

Wards relate directly to politics. The City of Chicago is divided into 50 voting districts, or wards, that in turn establish 50 City Council seats. These are meant to be essentially of equal size based on population, with each ward currently holding ~53,900 residents on average. The boundaries of wards can change based on information collected in the census every ten years through a process called redistricting.

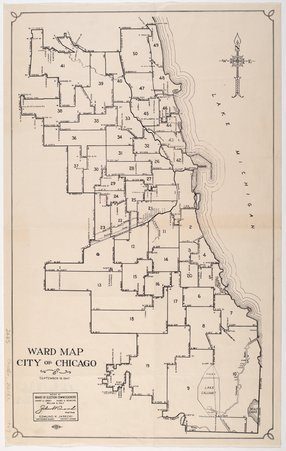

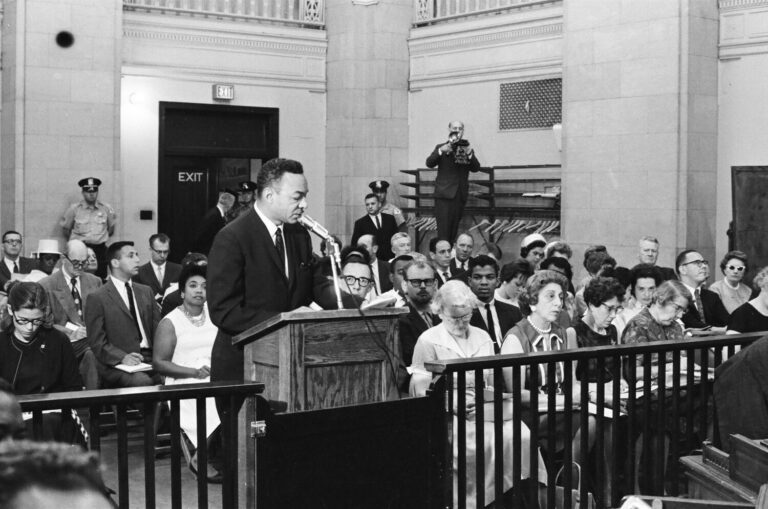

Members of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) speak to the Board of Education on issues of segregation in schools and gerrymandered school district lines. July 30, 1963, ST-60002620-0034, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Redrawing the ward maps can be a fraught and opaque process. For example, new district lines are proposed through an ordinance, which is a verbal description of the locational boundaries proposed, not an actual physical map. Additionally, gerrymandering, or the political manipulation of these boundaries, can create deep inequities by dividing communities into multiple wards making cohesive economic and social stability ongoing challenges.

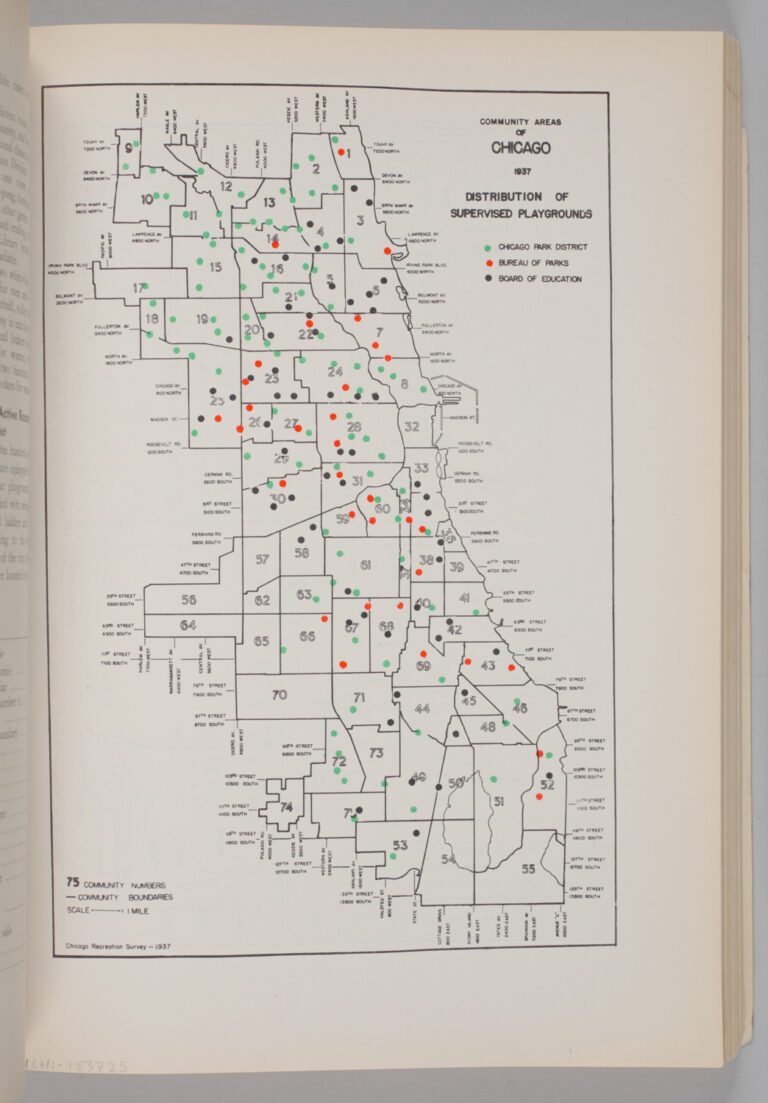

Community Areas of Chicago 1937: Distribution of Supervised Playgrounds, p. 105, 1937. CHM, ICHi-183725; Chicago Recreation Commision, author

When we say communities, as in the opening paragraph above, this can mean a lot of things—be it living in the same place, having similar interests or hobbies, sharing aspects of a cultural identity, and much more. However, “community” in Chicago also refers to the city’s officially defined community areas. Unlike neighborhoods, these are fixed divisions—each having roughly the same population within. In the late 1920s, Robert Park and Ernest Burgess mapped 75 community areas in Chicago based on information from the US Census Bureau, the boundaries for which are still largely unchanged. A small exception is the later additions of O’Hare (1956) and Edgewater (1980) to make the 77 community areas we know and use today. Areas were carefully delineated based on statistics like income, crime rates, and health information. These unchanging boundaries have proved useful for planning and studying purposes.

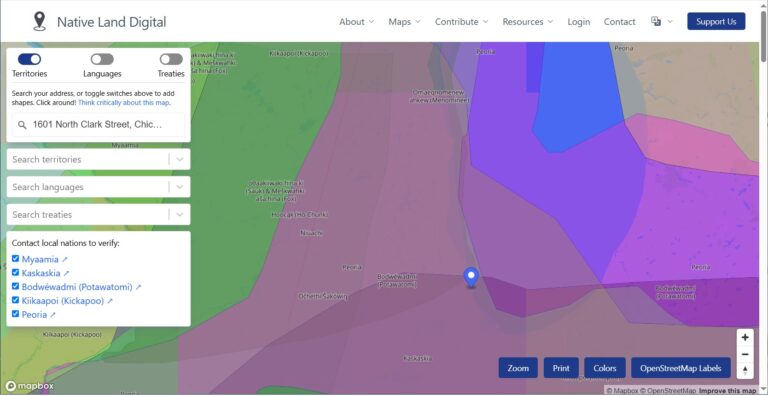

Map data provided by Native Land Digital. Used with permission for educational and non-commercial purposes.

However, they are not a full representation of how Chicagoans perceive the city nor how they define the places in which they live. An “area” is not the same as having a defined space for community or a space of belonging. Additionally, there are countless ways of conceptually thinking of one’s relationship to space and land relationally and fluidly. For example, the Native Land Digital map demonstrates ways to conceive of the Zhegagoynak/Zhigaagon/Zaagawaang/šikaakonki (Chicago) area through language, tribal territories, and treaties in stark contrast to the gridded system we see in most area maps.

A 2021 study on the concept of belonging and cultural institutions importantly notes that people who identify as Black, Latino/a/e, and Asian more often describe community through race or ethnicity, and people who identify as white more often think of community as a place or location. This closely relates to the idea of a “neighborhood,” which is conceptually and practically much more fluid and subjective than a geopolitically defined community area. Neighborhood boundaries and understanding of identity change through time and, for many Chicagoans, drive a stronger sense of place than a community area. Chicago neighborhoods are constantly changing in name and delineation, and today the city boasts more than 200 distinct neighborhoods, each holding claim to a sense of individual identity and local pride.

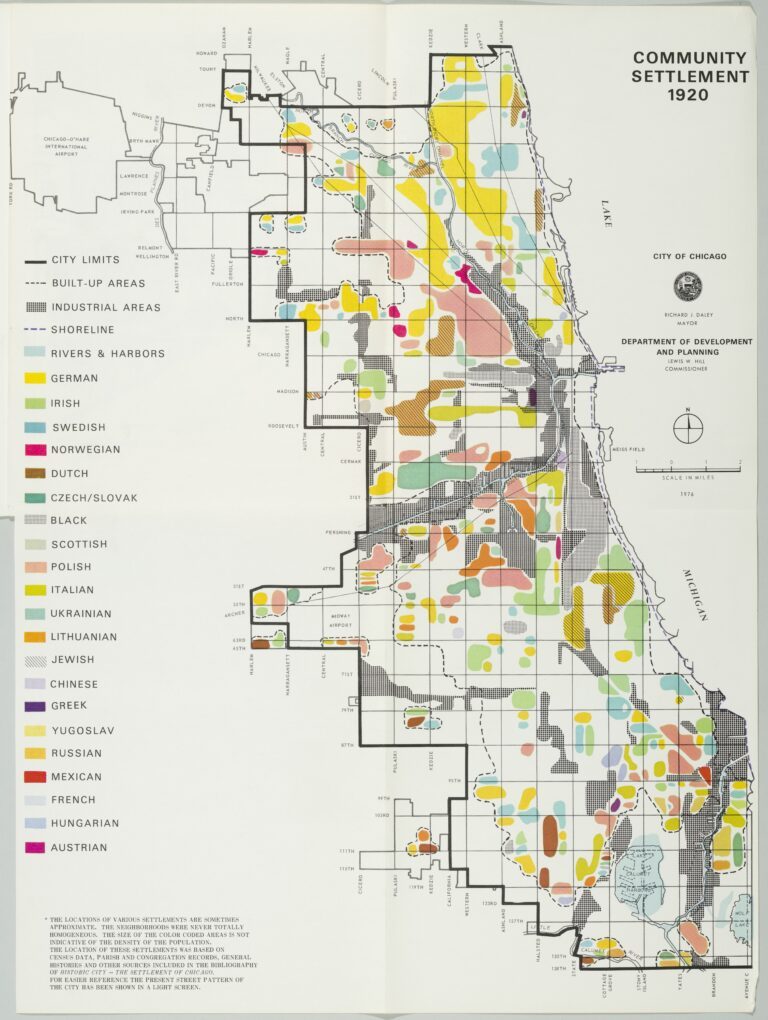

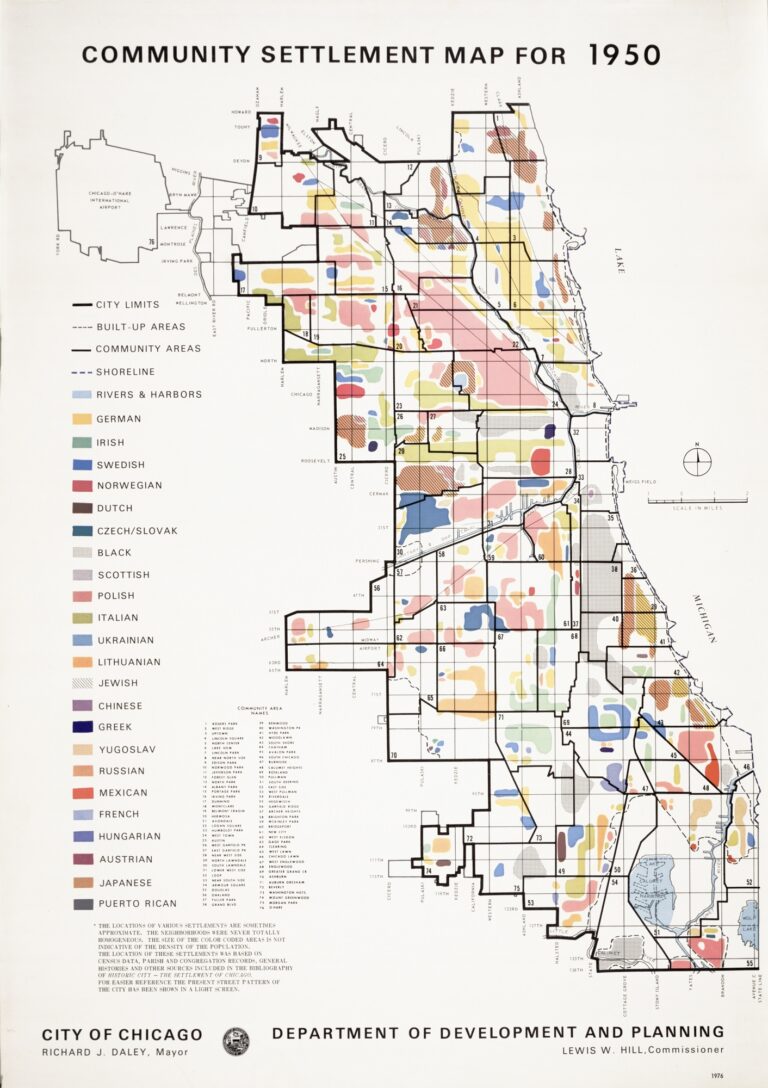

Community Settlement Map for 1920 and 1950 based on race and ethnicity, produced by the City of Chicago Department of Development and Planning, 1976, CHM, ICHi-182192 and ICHi-051194

Seeing Chicago as a city of neighborhoods often goes hand-in-hand with its “multiethnic” identity. This is generally thought of in terms of migration and how communities of different nationalities, ethnicities, races, and languages created space for themselves in the city. Henry C. Binford called this “multicentered Chicago,” arguing that the idea of a “neighborhood” is a vague and contested concept. Instead, Binford claimed we should look at the city as a series of “spatial subcommunities” that have innumerable instances of human interaction and diverse histories.

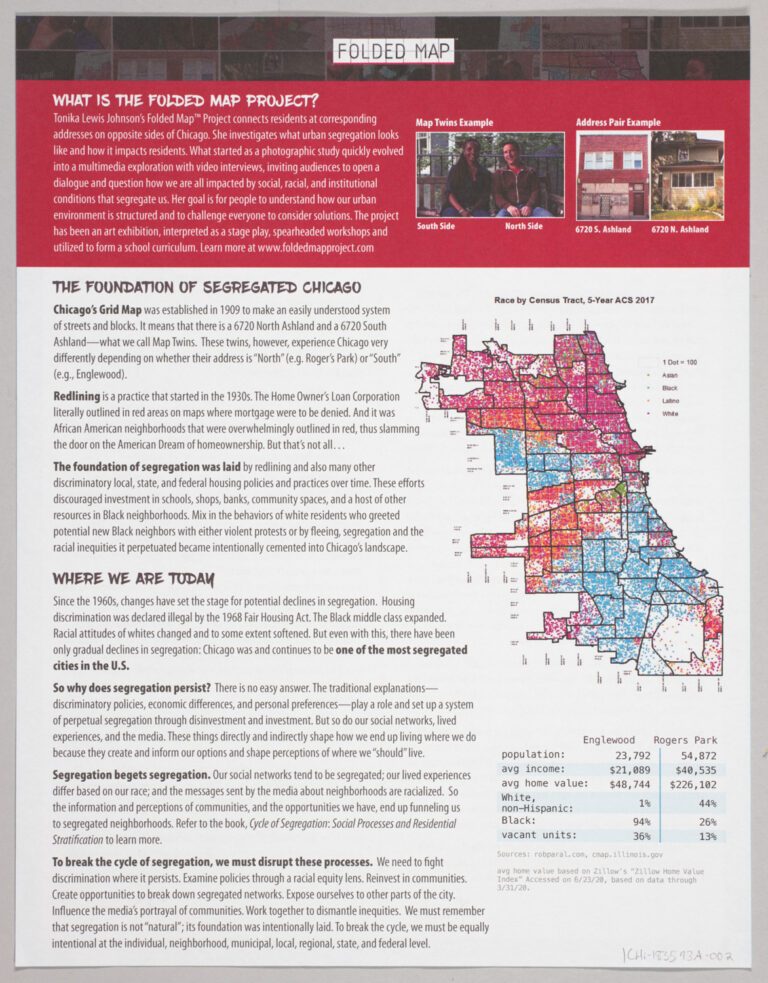

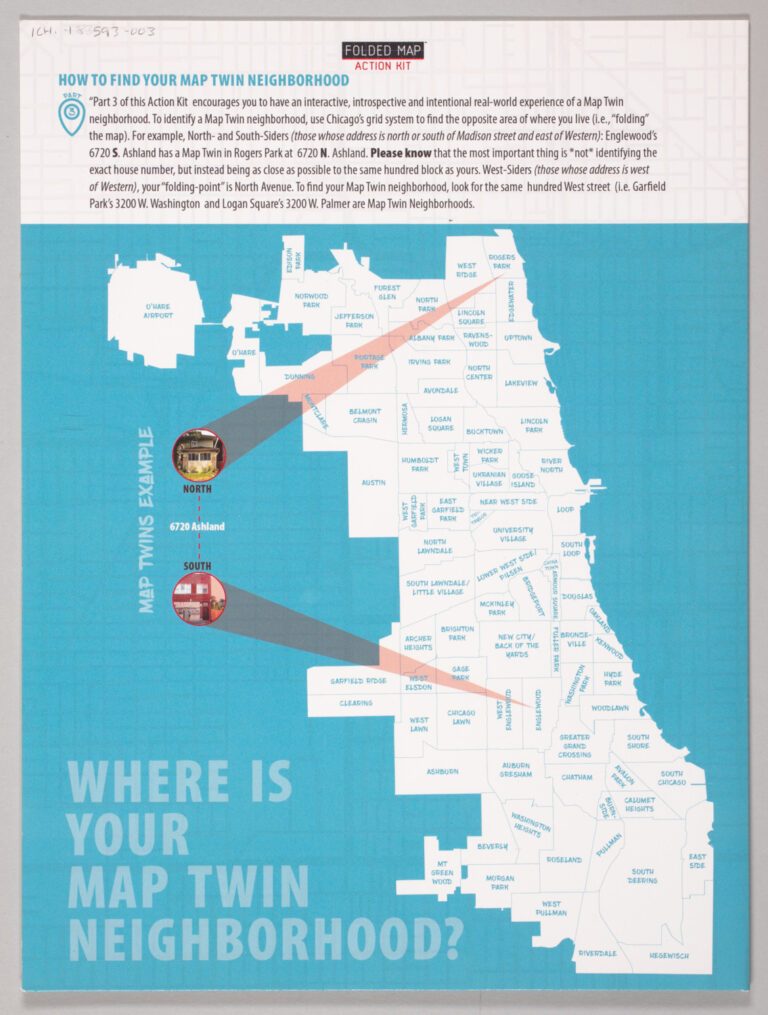

Two pages from the Folded Map Action Kit, a project to connect people living on the North and South Sides of Chicago with each other using the grid street address system to highlight disparities between neighborhoods. Folded Map © 2020, Tonika Lewis Johnson and Maria Krysan. All rights reserved. Kit design by JNJ Creative, LLC; CHM, ICHi-183593A-002, ICHi-183593-003

A related spatial legacy is Chicago’s identity as one of the most segregated cities in the US. In Chicago, segregation has been notably decreasing, and yet it remains the fourth most segregated city in the country, according to data from 2019. These recent studies also show that for many cities across the country, segregation is growing, not declining, with the Midwest disproportionately represented.

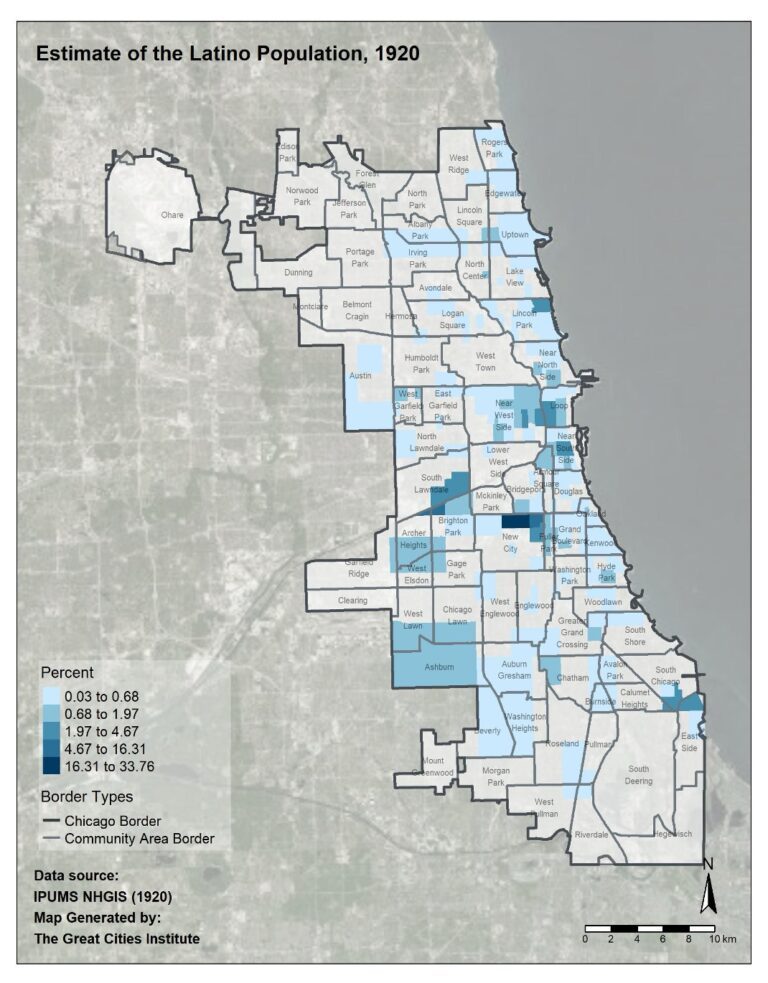

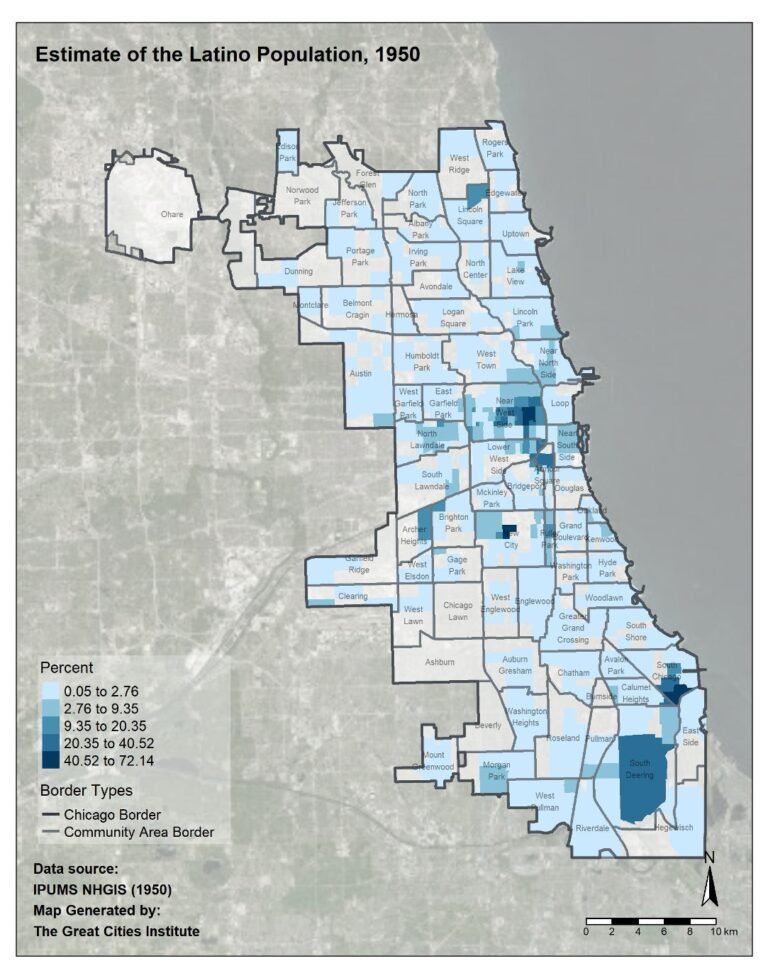

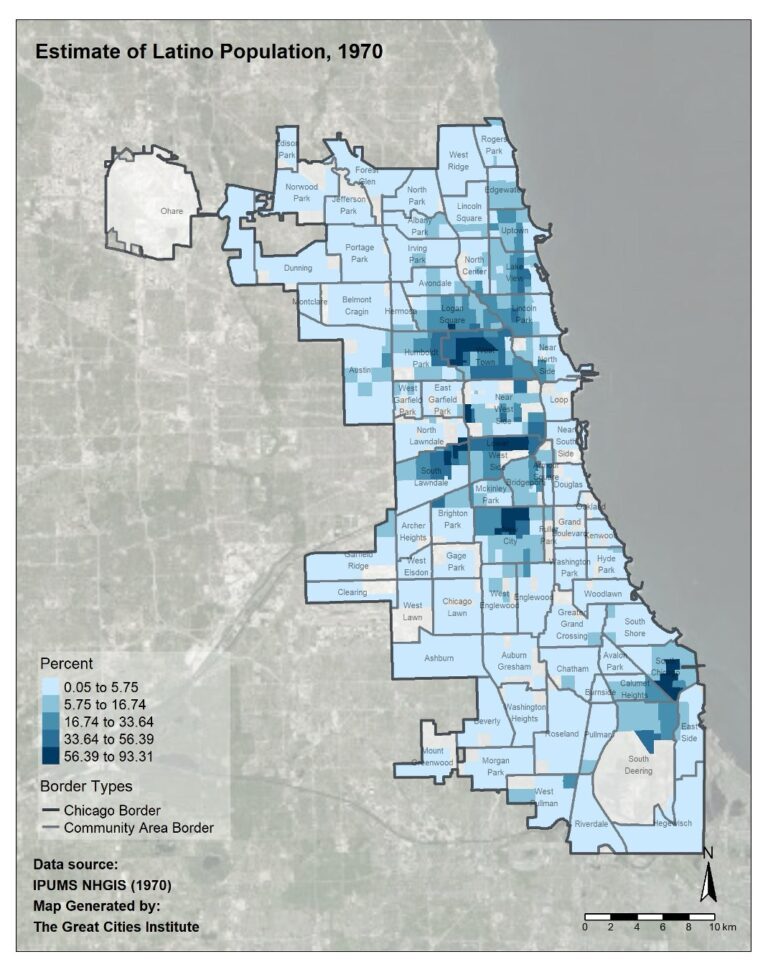

Maps depicting the “Estimate of the Latino Population” in Chicago, 1920, 1950, and 1970. Maps courtesy of Great Cities Institute at University of Illinois Chicago

In the context of Aquí en Chicago, we think about how communities make space for themselves in the city through many ways, including neighborhoods that Latino/a/e communities strongly identify with or have historically called home. These three maps come from a series of maps created by the Great Cities Institute at the University of Illinois Chicago for Aquí en Chicago. They show the demographic distribution of Latino/a/e people across Chicago through time and the evolution of making space from core neighborhoods in the 1920s such as the Southeast Side, Calumet, Back of the Yards, and East Chicago (known as the colonias) to Latino/a/e presence in nearly every part of the city and broader suburban Chicagolandia today.

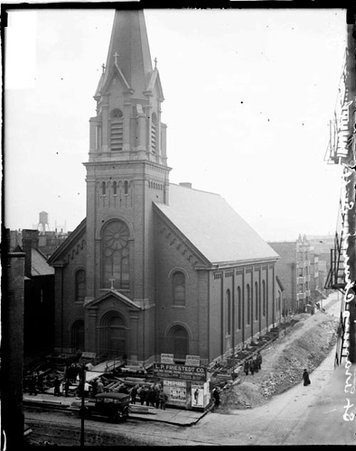

St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church on the Near West side is an example of ethnic succession, built for the German and German American community and later became Latino/a/e majority in attendance.

(L) St. Francis of Assisi Church, 813 W. Roosevelt Rd., Chicago, 1917. DN-0067872, Chicago Daily News negatives collection, CHM

(R) Exterior view of J. J. Strnad Real Estate with a sign advertising in Spanish and English, 1801 Blue Island Ave., Chicago, January 8, 1961. CHM, ICHi-051411; John McCarthy, photographer

Key to this idea of Latino/a/e neighborhoods is the concept of ethnic succession, in which different ethnic or racial communities occupy different places through time. When we consider evolving neighborhood identities, we see how shifts in elements like who sees themselves as represented in the neighborhood, what are the community anchors, whose image is on the advertisements, and what language is on the business signs, all combine to create a sense of place. That place, that sense of belonging, creates a sense of identity. As this shifts through time, communities, in turn, feel like a sense of ownership may shift as well.

Residents protest the designation of the area around Halsted and Harrison Streets as the site of the new University of Illinois campus, March 19, 1961, ST-17600243, Chicago Sun-Times Collection, CHM

These ethnic shifts do not happen in a vacuum of neutral migration and movement by families and communities. Urban renewal, economic displacement, forced migration, racial segregation, and gentrification are key driving factors for how and why neighborhoods may shift over time. For example, in the 1950s and ’60s, thousands of people were displaced to make way for the Eisenhower Expressway and the University of Chicago Circle Campus. Neighborhoods like Pilsen (as part of the Lower West Side community area) and Little Village (as part of the South Lawndale community area) shifted from being predominantly European residents (in this case, Czech and Polish) to Latino/a/e. Communities make and keep places, in many ways and for many different reasons, defining and making Chicago (and beyond) the city we know today.