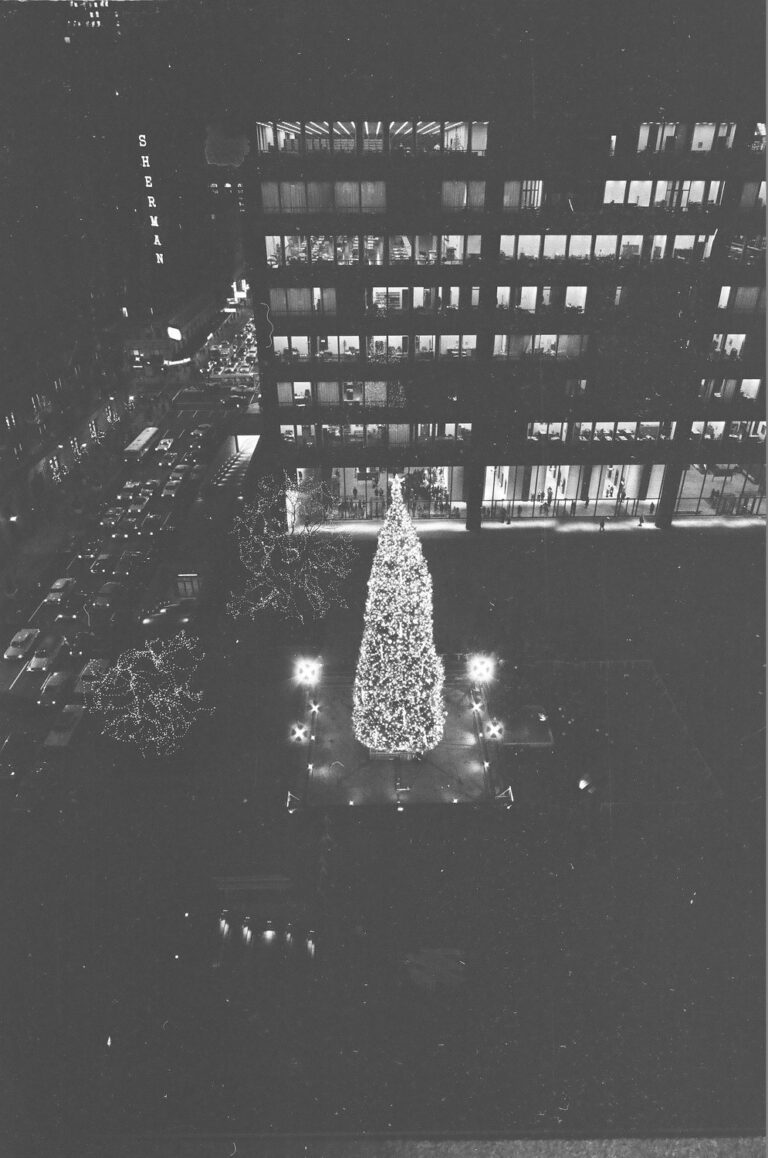

The view looking down at the Civic Center Christmas tree after Mayor Richard J. Daley turned on the lights, December 9, 1966. ST-80004582-0005, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

It’s been said a million times. The sequel never lives up to the original. And while that generally holds true, when exceptions happen, they’re particularly noteworthy. When The Empire Strikes Back was released in 1980, it pushed the boundaries of sci-fi films in a way many thought impossible, shattering the precedent set by its predecessor, A New Hope. Similarly, Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight made crowds fall in love and appreciate villains just that much more. In the rapidly forgettable world of holiday film sequels, Home Alone 2: Lost In New York pulls no punches compared to its predecessor, standing as a Christmas movie staple.

Released on November 20, 1992, Home Alone 2: Lost in New York is the sequel to 1990’s iconic holiday box office hit, Home Alone. When it opened, it shattered the record for the largest November opening weekend, with more than $31 million in revenue, and would go on to gross just over $100 million in three weeks. It would ultimately rank as the third-highest grossing film of 1992.

The film takes all the antics and hijinks that made the first a hit and amps them up to the next level, with the lovable Kevin McCallister, played by Macaulay Culkin, outrunning and outsmarting his rivals, the Wet Bandits, after being separated from his family and accidentally landing in New York instead of Florida for the family’s holiday vacation. But while Kevin may have landed in New York, his film was set inside the universe of the late director John Hughes, which often meant one thing. If it could be set in and filmed in Chicago, it would be. So, with a bit of Hollywood camera magic and set design, even the keenest of observers were tricked into believing that Kevin left suburban Winnetka and went 800 miles east to the Big Apple.

Although a good amount of the film was shot on-site and in-studio, some of the most iconic scenes were still cleverly filmed in Chicago. Some of the earliest scenes in the movie were filmed in Winnetka and Evanston and in nearby O’Hare International Airport. The airport actually returns later in the film, serving as the double for John F. Kennedy International Airport in Queens, where Kevin was alerted that he had once again been separated from his family.

O’Hare International Airport’s new international terminal on the day of its ribbon-cutting ceremony, May 27, 1993. ST-30002446-0291, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

While Kevin’s luxurious stay at the Plaza Hotel in New York features the hotel’s lobby and exterior, his iconic penthouse suite was actually located in another hotel that looms large in Chicago history—the Hilton Chicago on South Michigan Avenue. Originally named the Stevens Hotel, the Holabird and Roche-designed building opened its doors in 1927, and it was known as a “city within a city” due to its near-endless amenities and 3,000 guestrooms. At the time, it was believed to be the world’s largest hotel. The business would eventually be acquired by hotel magnate Conrad Hilton, and he would rename the building after himself, highlighting the importance of the building. Kevin, using his dad’s credit card, checked himself into the hotel’s Conrad Suite, also named after the man himself. The pool scene featuring poorly-fitting swim trunks was filmed a stone’s throw away at the Four Seasons Hotel on Delaware Place.

The Stevens Hotel (now the Hilton) along Michigan Avenue in 1927. CHM, ICHi-076260; Kaufmann & Fabry Co., photographer

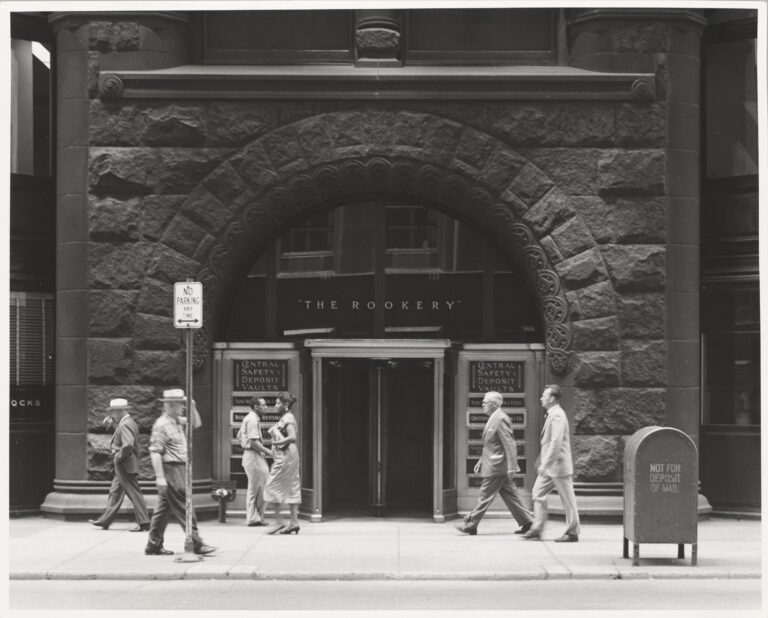

Since no excursion to Chicago (or “New York”) is complete without some shopping, Duncan’s Toy Chest captured every kid’s dream toy store. The magic behind Duncan’s was created in two parts. The store’s exterior belongs to the historic Burnham and Root-designed Rookery Building on South LaSalle Street in the Loop. Meanwhile, the store’s interior was crafted by making use of a northside movie palace, the iconic Uptown Theatre, originally owned by the Balaban and Katz movie chain. The theatre’s luxurious interior was meant to mimic that of the Palace of Versailles and was one of the first buildings of its size to have air conditioning. Throughout its run, the theater presented everything from silent movies and vaudeville shows to major acts like Prince and The Who. It closed its doors in 1981. What a lucky boy Kevin was to be inside!

Entrance to the Rookery Building at 209 South LaSalle Street, July 30, 1957. CHM, ICHi-093046; Glenn E. Dahlby, photographer

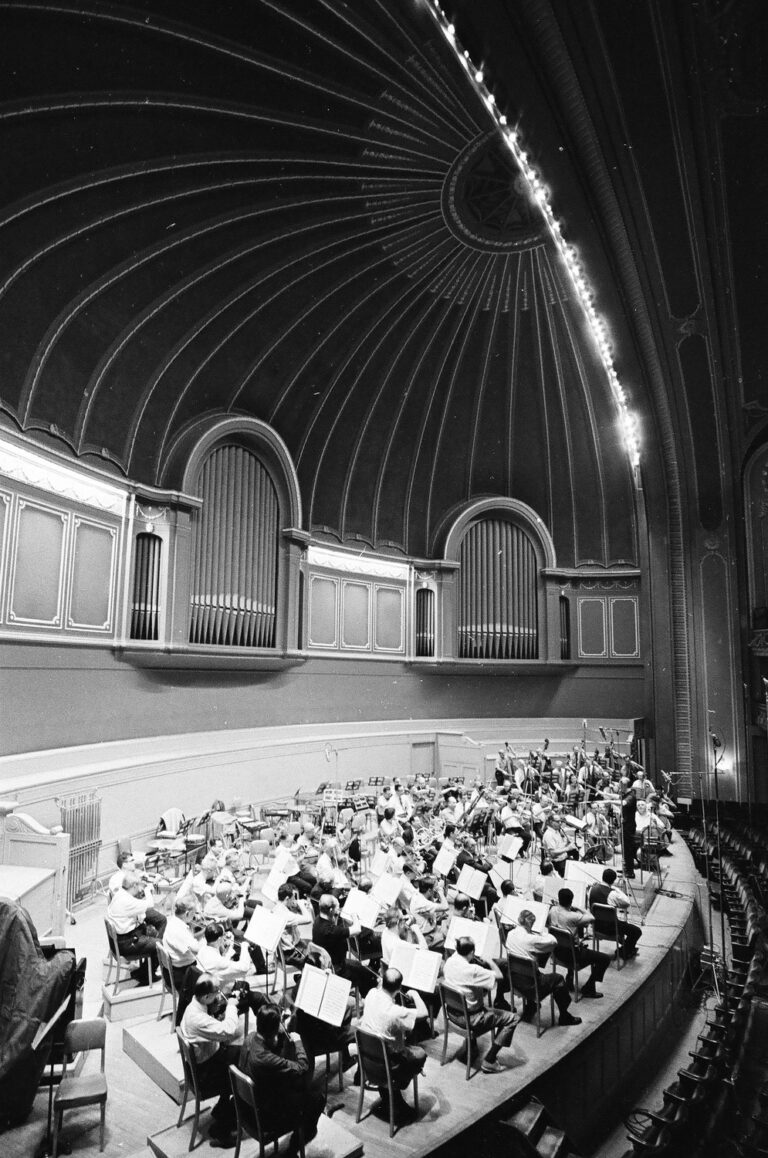

Finally, in what was perhaps the most creative use of Chicago landmarks to double as locations in New York, Kevin’s bird’s eye viewing of the orchestra performing “O Come On All Ye Faithful” again makes a convincing (and we’d argue, better-looking) double of Carnegie Hall by using the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Symphony Center on the corner of Michigan Avenue and Adams Street in the Loop as the performance space.

Benny Goodman records with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra on the performance stage at Orchestra Hall, 220 S. Michigan Ave., June 18, 1966. ST-19070395-0011, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Today, both Home Alone films continue to be cult classics. The Hilton Hotel where Kevin stayed even offers a themed stay simply titled “The Kevin Package,” which allows guests to stay in the Conrad Suite and live out their Home Alone dreams, personal cheese pizza included. For those looking to relive even more nostalgia, every December to mark the holidays, Easy Street Pizza in nearby Park Ridge transform into Little Nero’s Pizza, the fictional restaurant from the first installment of the franchise, where no less than 10 pizzas were ordered at a cost of $122.50 in 1990 dollars. Adjusted for inflation, that would be $281.12 today.

Additional Resources

- To learn more about the history of film in Chicago, see the entry on “Film” in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- In 2023, the original Home Alone was added to the National Film Registry. To read more about it and the rest of the additions, check out this blog post from the Library of Congress