CHM collections intern Araceli Medina recaps her work this past summer assisting with the ongoing inventory of the Decorative and Industrial Arts collection. Through the inventory process, Medina saw first-hand how objects can tell stories that help us understand the past as it was lived.

The process of inventorying a museum collection is important and requires a lot of time, but it is always full of surprises. This summer, I worked as an intern for the Decorative and Industrial Arts collection, and I got to learn more about several centuries worth of objects from the Charles F. Gunther Collection.

Medina (left) and fellow intern Elise O’Neil transport a cart of artifacts. All photographs by Chicago History Museum staff

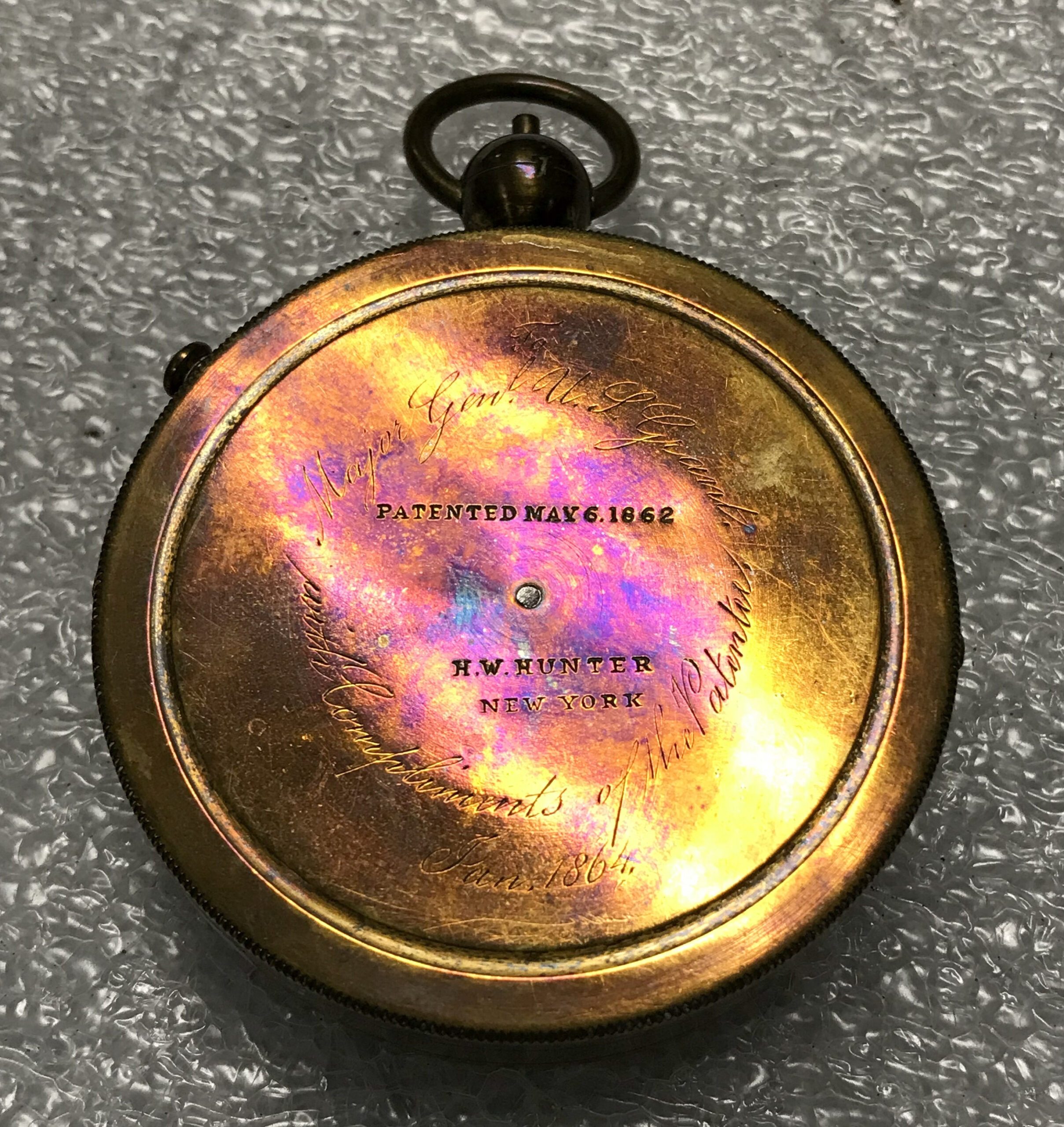

Objects have value imbued upon them in varying ways and this was quite evident through the inventory process. I got to see what objects people valued enough to save for future generations and to consider how certain values shift over time. People go through many lengths to safeguard relics to commemorate famous individuals. One example is Ulysses S. Grant’s compass, which he obtained during the Civil War. He most likely valued it because it was useful in his daily life. However, other objects seemingly were not of value to the famed individual, but their mere association warrants attention from future collectors.

Inside and back of Grant’s compass. Inscription reads: “Major General U.S. Grant with Compliments of the Patentee.” CHM, 1935.164a-b

Another example is a fruit knife that once belonged to Mary D. Green. She was given this knife as a gift by Tad Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln’s son, since she was his school teacher. She herself is not a known figure but because of her association with Lincoln, this object’s context and value changes.

Mary D. Green’s knife. Inscription reads “M.D.G.” CHM, 1919.36

History becomes alive as one goes through the cabinets that store the collection. This is why museums are of great importance. They safeguard and collect objects so that people can later see what, for example, a telegraph cable from the early twentieth century looked like, or one can imagine the life of a soldier during the Civil War by looking at a small wallet they carried or a powder horn they decorated on their downtime. With multiple centuries worth of objects within the Museum’s collection, one gets a sense of how our understanding of the world and the things we value change over time.

One of the earliest objects we found is a globe made in 1603 by Gulielmas Nicolai. The globe functions as a way to look at the world through the lens of a European individual from the seventeenth century. For example, Cuba is much larger on the globe than we know it to be today, as is Florida, which is shown as making up most of the US. Additionally, the Pacific Ocean is so narrow it appears more like a river than an ocean. This demonstrates the unfamiliarity of the Western Hemisphere at this time and how it was slowly being pieced together.

Seventeenth century globe. CHM, 1938.38a-b

Another snapshot of history we found as we inventoried the collection was a bracelet made of bone during the Civil War by a Union soldier. The words “Libby Prison” are inscribed on it. This is just one of many artistic pieces we found made at the Confederate Libby Prison, and when contextualized it keeps a record of what life was like in the prison.

The center heart piece of this bracelet is inscribed with “Bell Island VA. Aug 11 1868.” CHM

The value we place on objects differs for many reasons, and through the inventory process I observed distinct valorizations through different historical lenses. Ultimately, I learned while investigating the objects in this collection that keeping these value differences in mind helps to make sense of the context of their time as well as the present.

- Read more on managing collections storage.

- Read more posts on collections inventory.