Here you’ll find digital content for Aqui en Chicago.

World’s Columbian Exposition Pavilions / Pabellones de la Exposición Universal Colombina

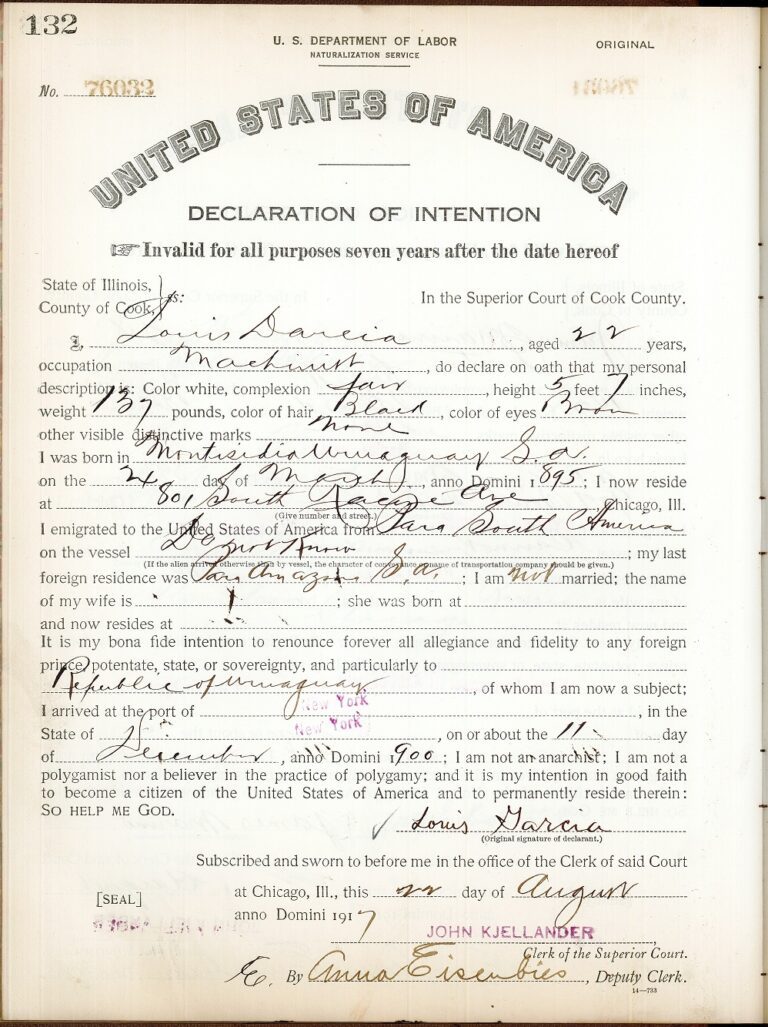

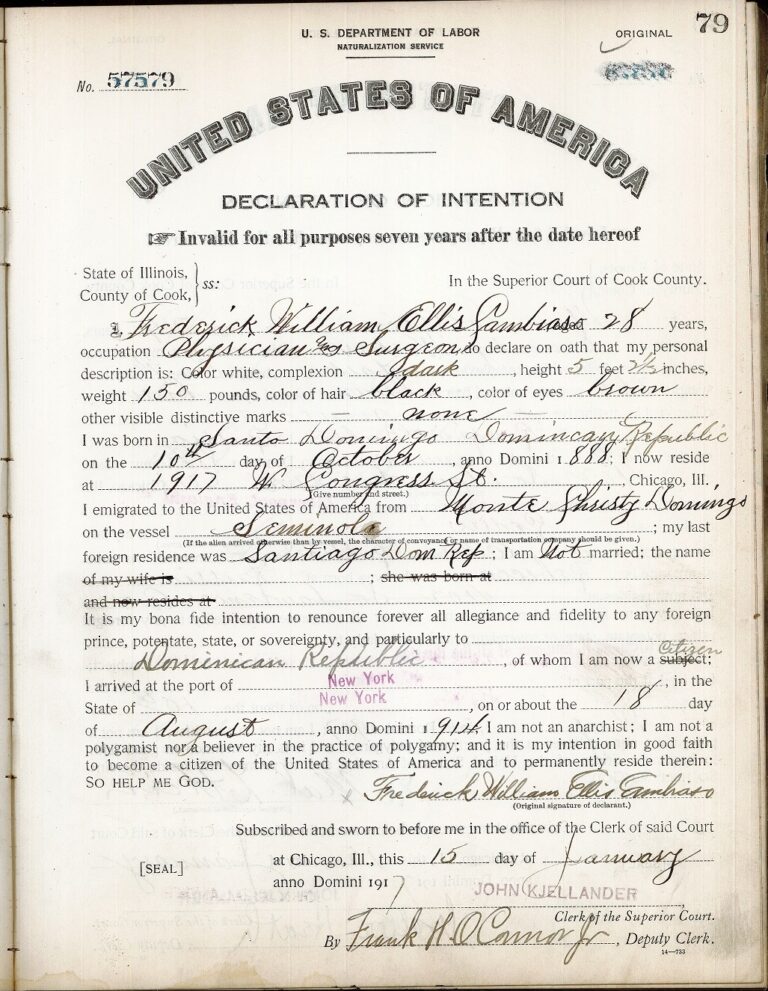

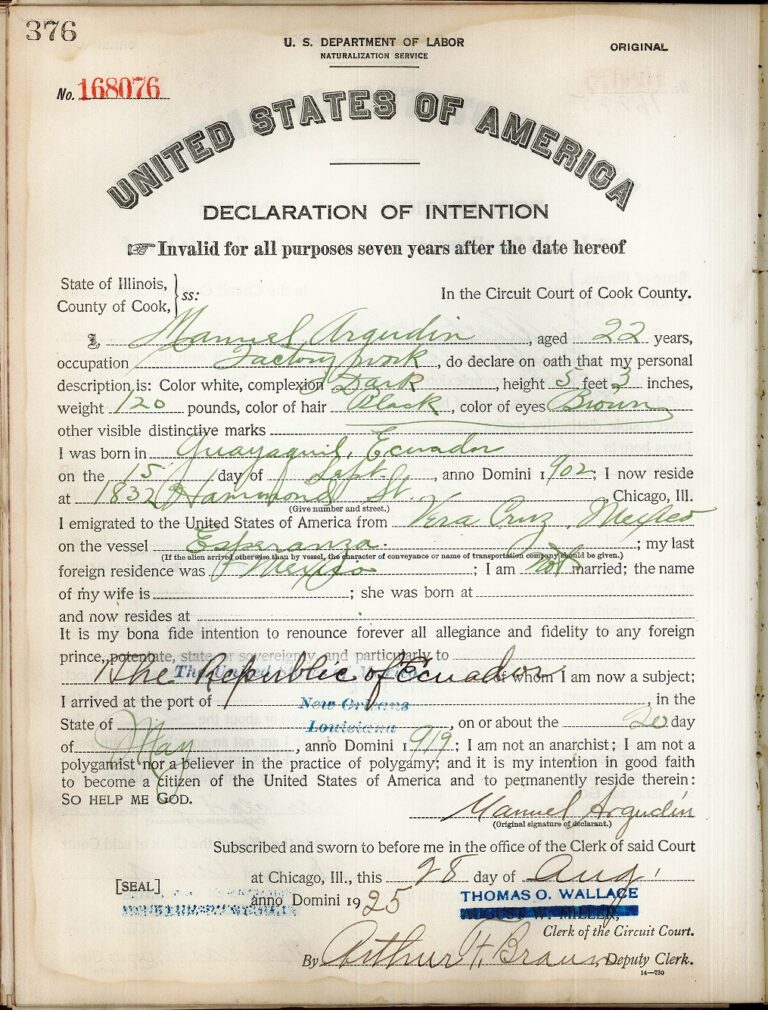

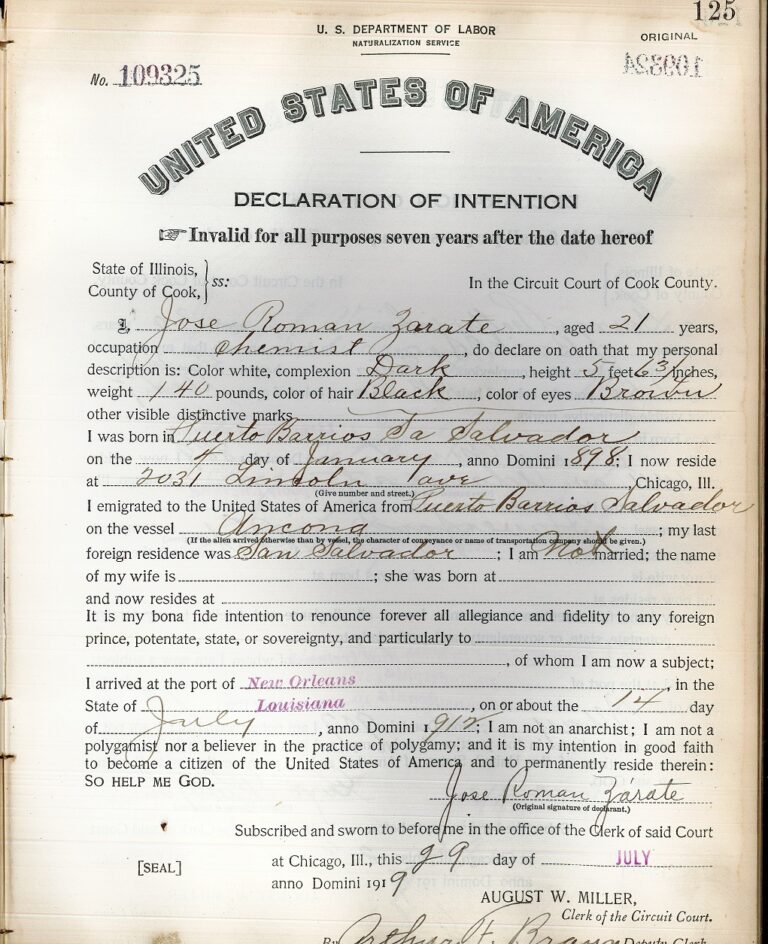

Naturalization Certificates / Certificados de naturalización

Maria Mangual in Conversation / Maria Mangual habla

Interview with Reyna Matoaka Ortiz / Entrevista con Reyna Matoaka Ortiz

Interview with Anton Miglietta / Entrevista con Anton Miglietta

“The American Hen” Eggs / Huevos de “La gallina americana”

Interview with Tania Córdova / Entrevista con Tania Córdova

Interview with Adriana Portillo-Bartow / Entrevista con Adriana Portillo-Bartow

Interview with Elvira Arrellano (English Translation) / Entrevista con Elvira Arrellano (transcripción)

Future Homes Artists / Artistas de Hogares futuros

Interview with Josue Siu / Entrevista con Josue Siu

World’s Columbian Exposition Pavilions / Pabellones de la Exposición Universal Colombina

Venezuela

The Venezuela Pavilion was designed by architect J. B. Mora and was crowned by a statue of Simón Bolívar (liberator of Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Panama, and Bolivia from Spain) at the east end and Christopher Columbus at the west. The inside featured notable works by Venezuelan artists Arturo Michelena and Cristóbal Rojas.

Guatemala

Another design by J. B. Mora, the Spanish Revival–style Guatemala pavilion ceremonially opened as part of “Central American Day at the Fair” with a delegation of diplomats present, including Manuel Lemus and Leon Rosenthal. In addition to agricultural, mineral, and other products on display, the inside featured a giant marimba with award-winning performances by musicians Samuel and Pedro Chavez, Lucio Castelanos, and Antolin Molina.

Costa Rica

Costa Rica’s Federal-style pavilion by James G. Hill opened as part of “Central American Day at the Fair” alongside Guatemala. It exhibited woods, minerals, animals, medicinal plants, and other products including coffee.

Colombia

Colombia’s pavilion opened to the public on July 20 to mark the anniversary of its independence from Spain. Designed by J. B. Mora, its displays featured an array of natural resources, including plants, minerals, birds, butterflies, and coffee.

Brazil

The Brazilian pavilion was designed by Francisco Marcelino de Sousa Aguiar in a French Renaissance style. The displays inside centered Brazil’s rich and abundant natural resources, including rubber and coffee.

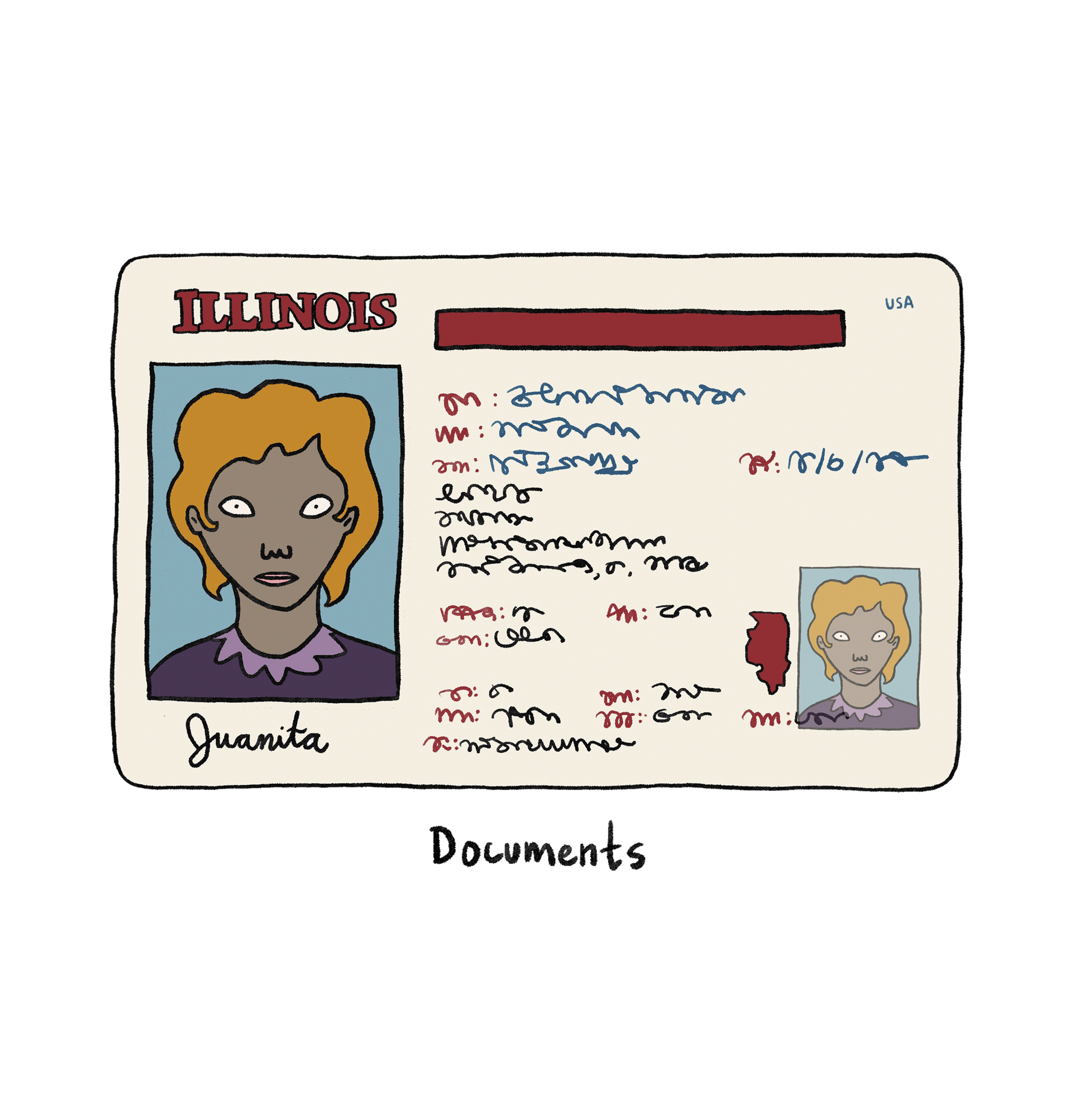

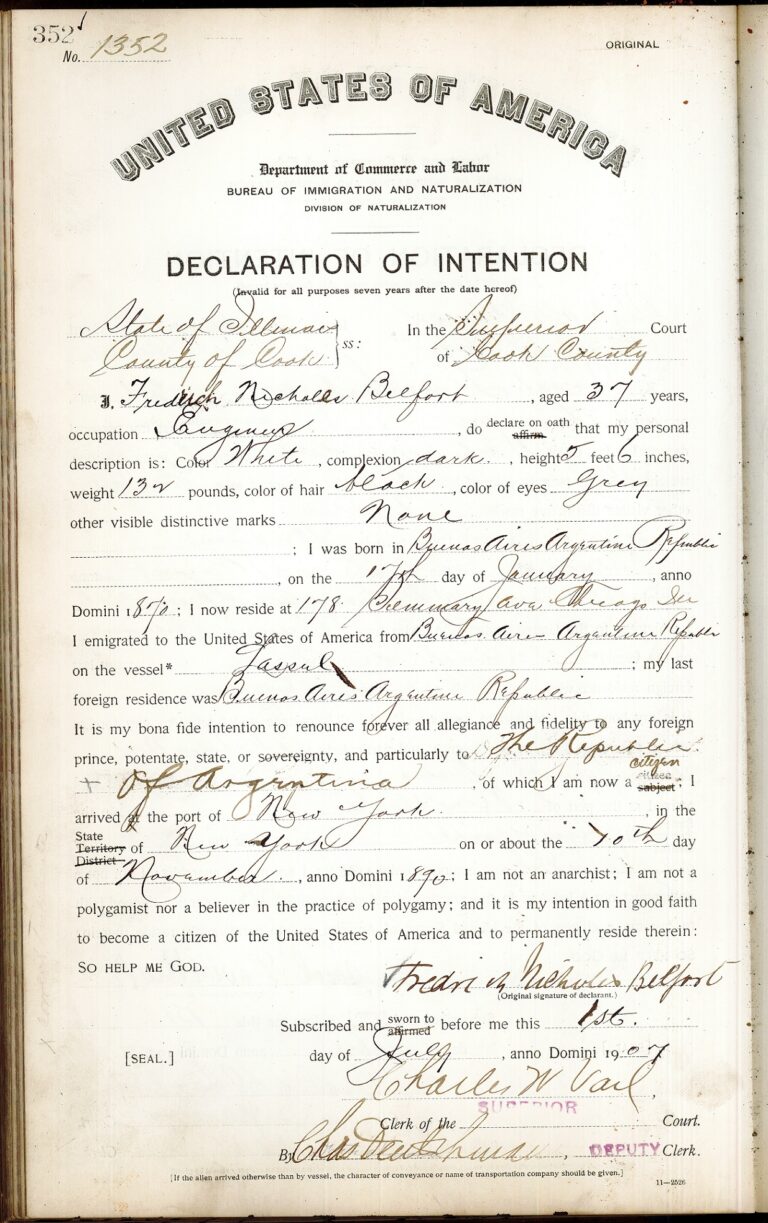

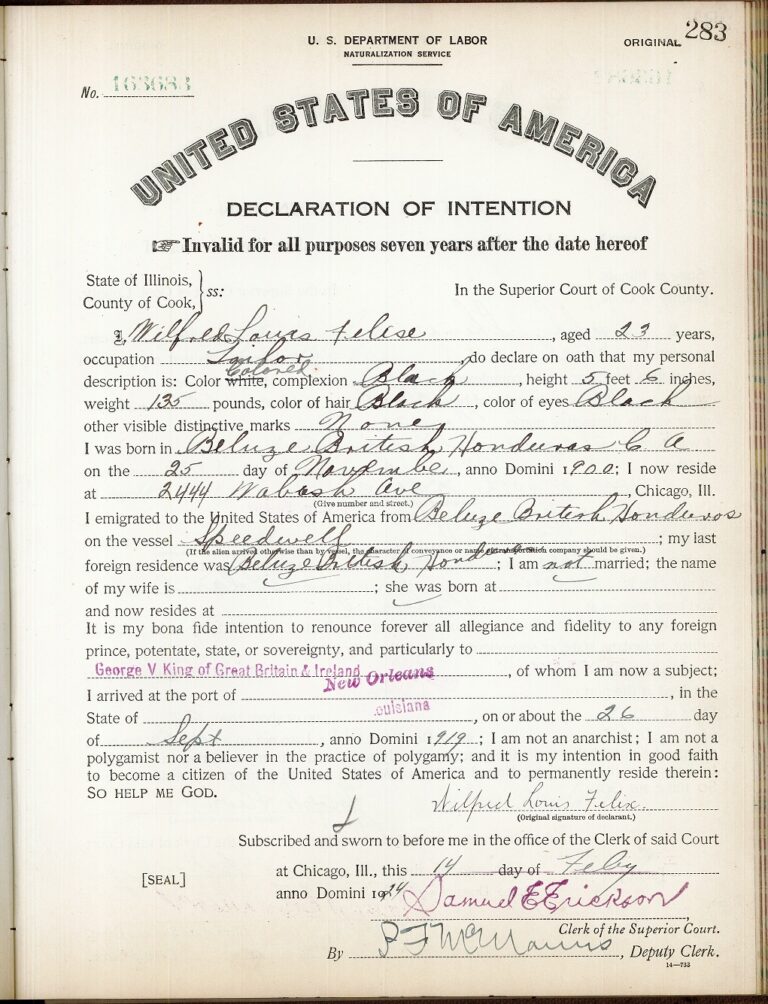

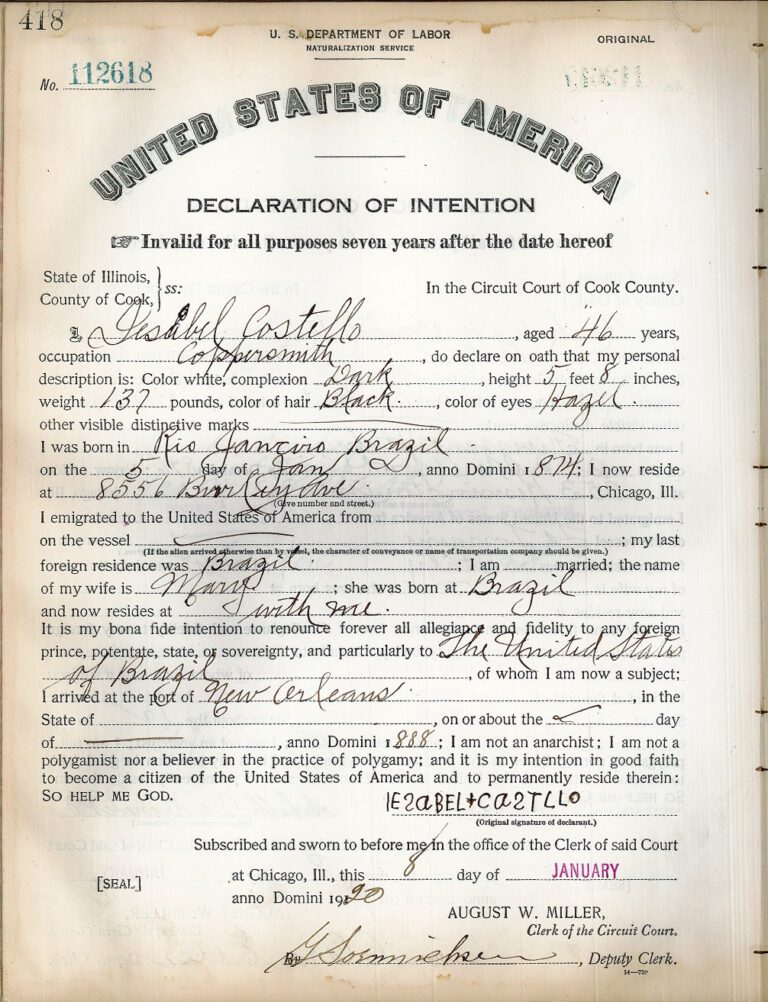

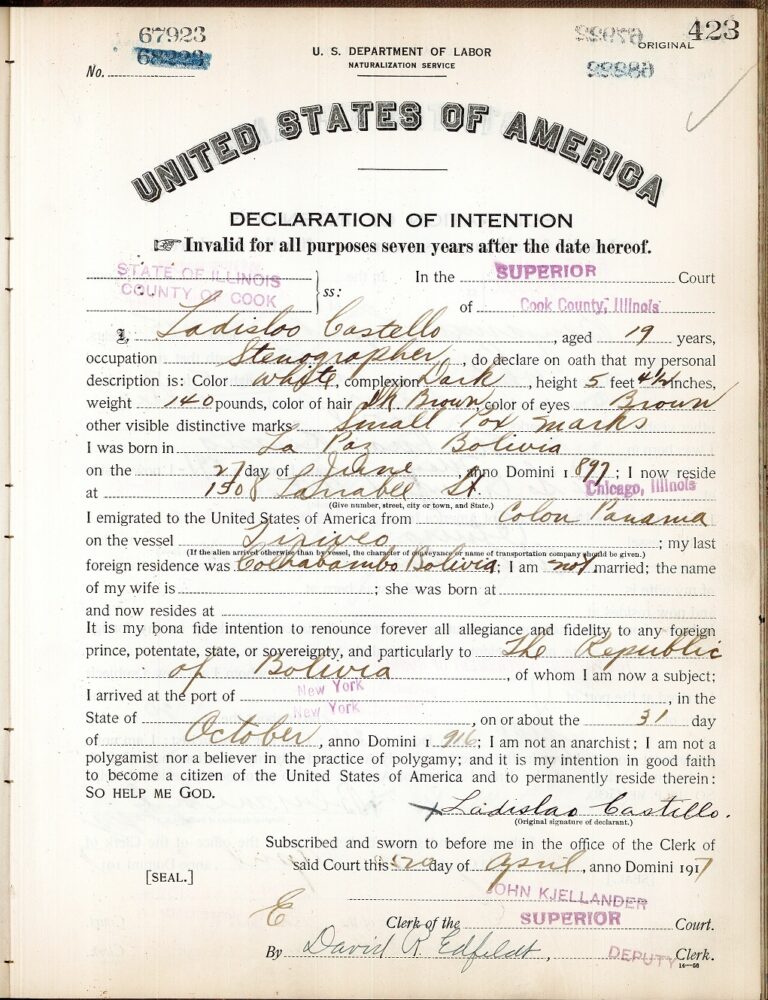

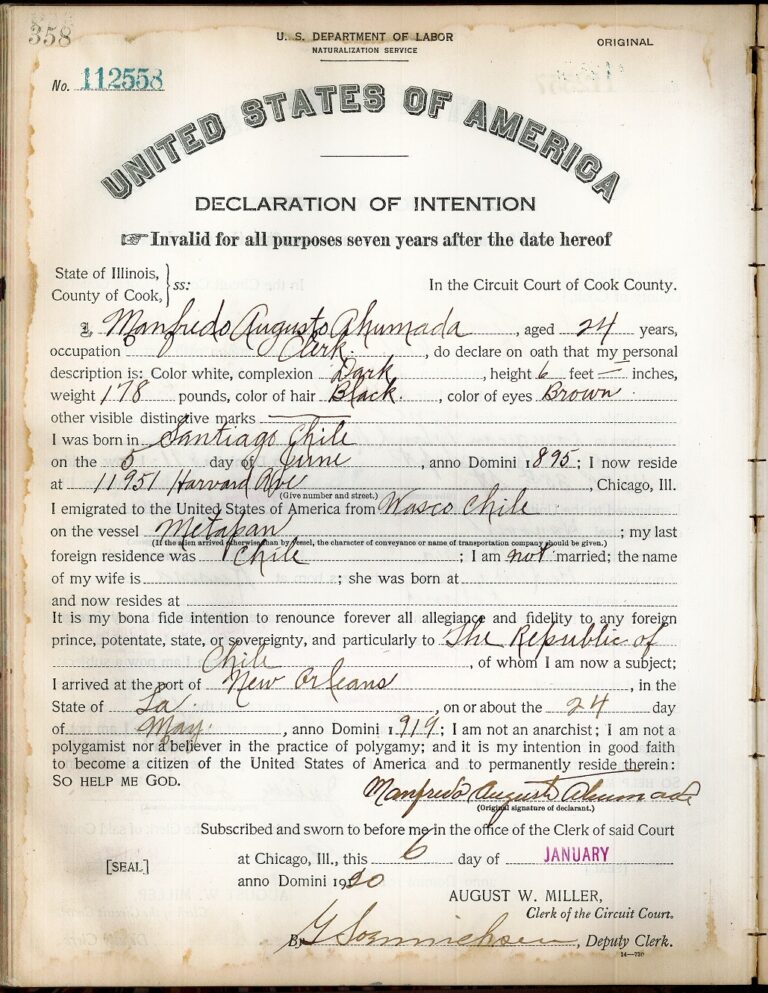

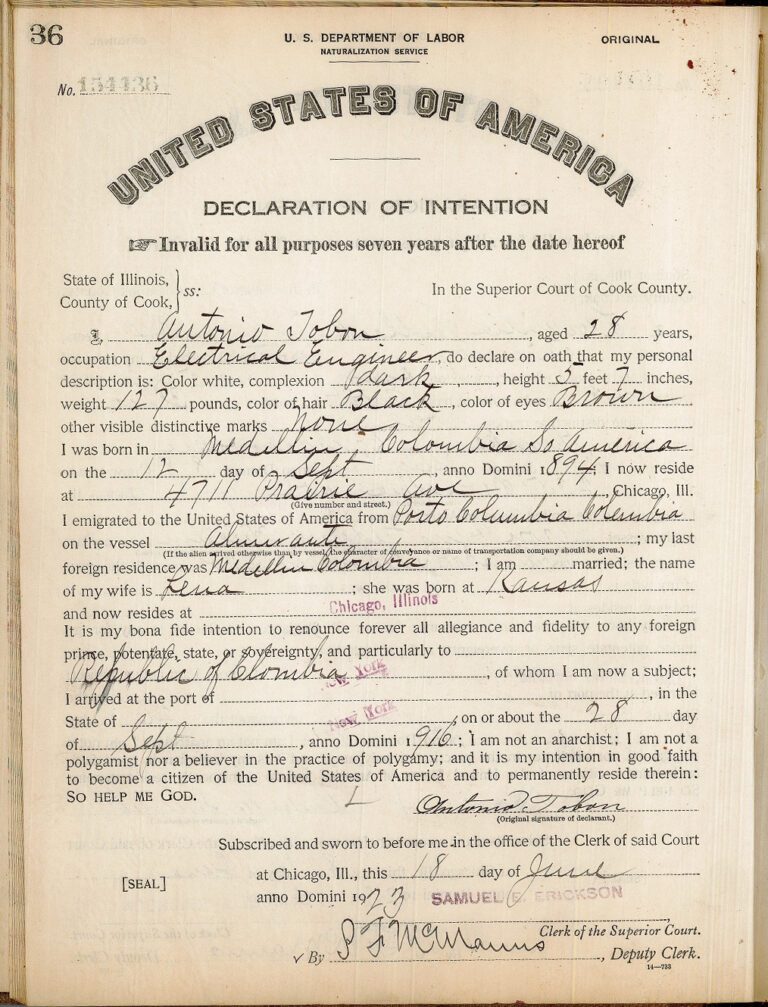

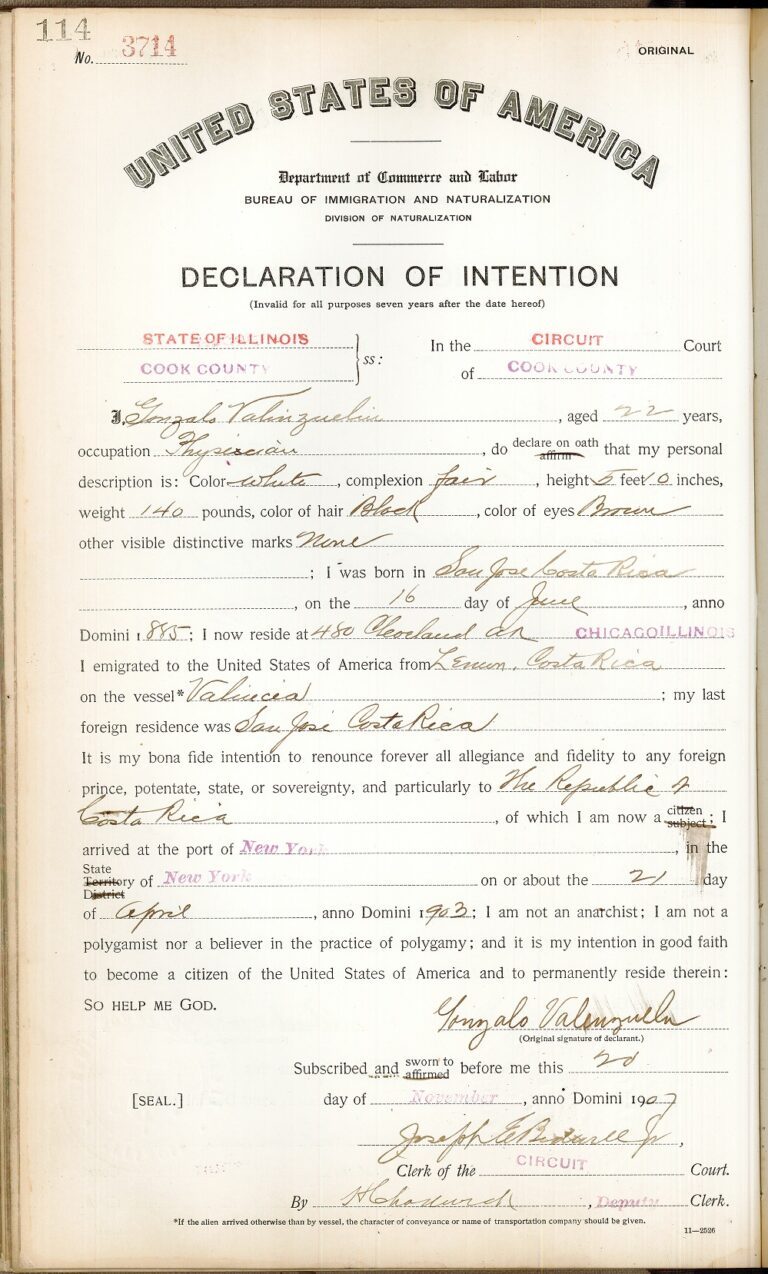

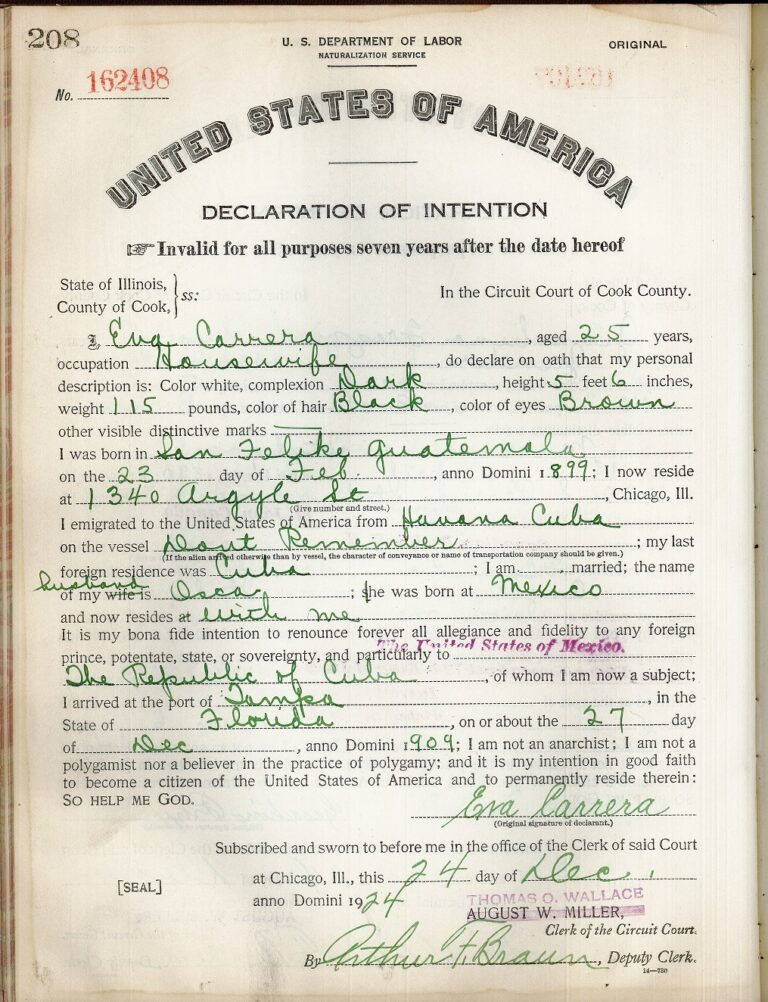

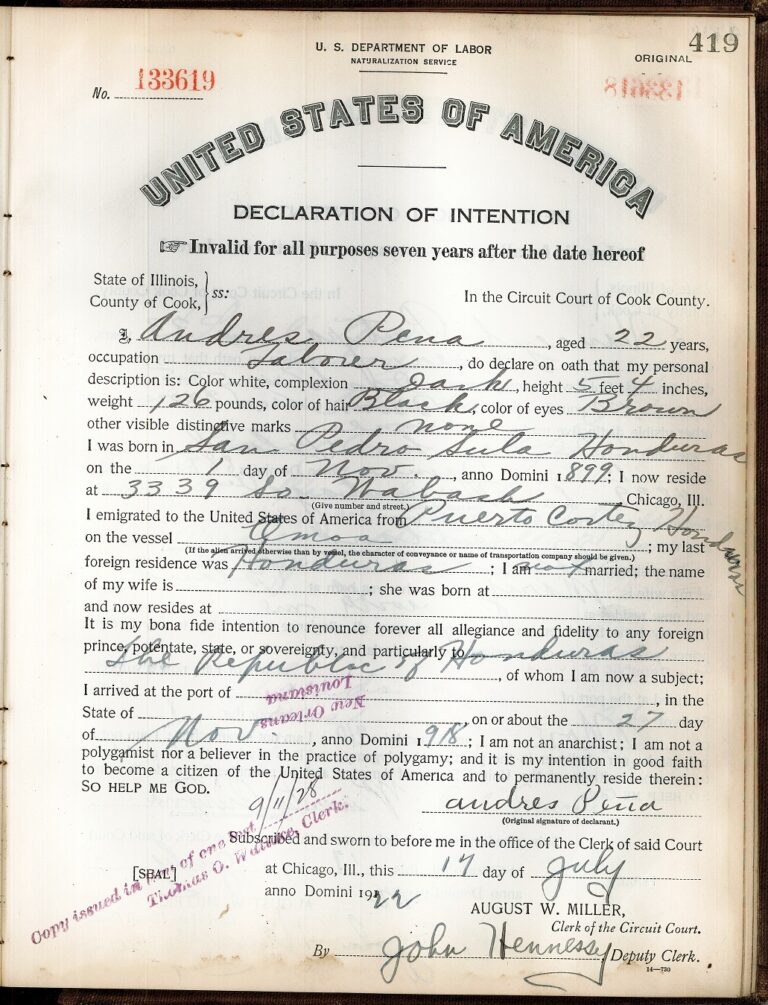

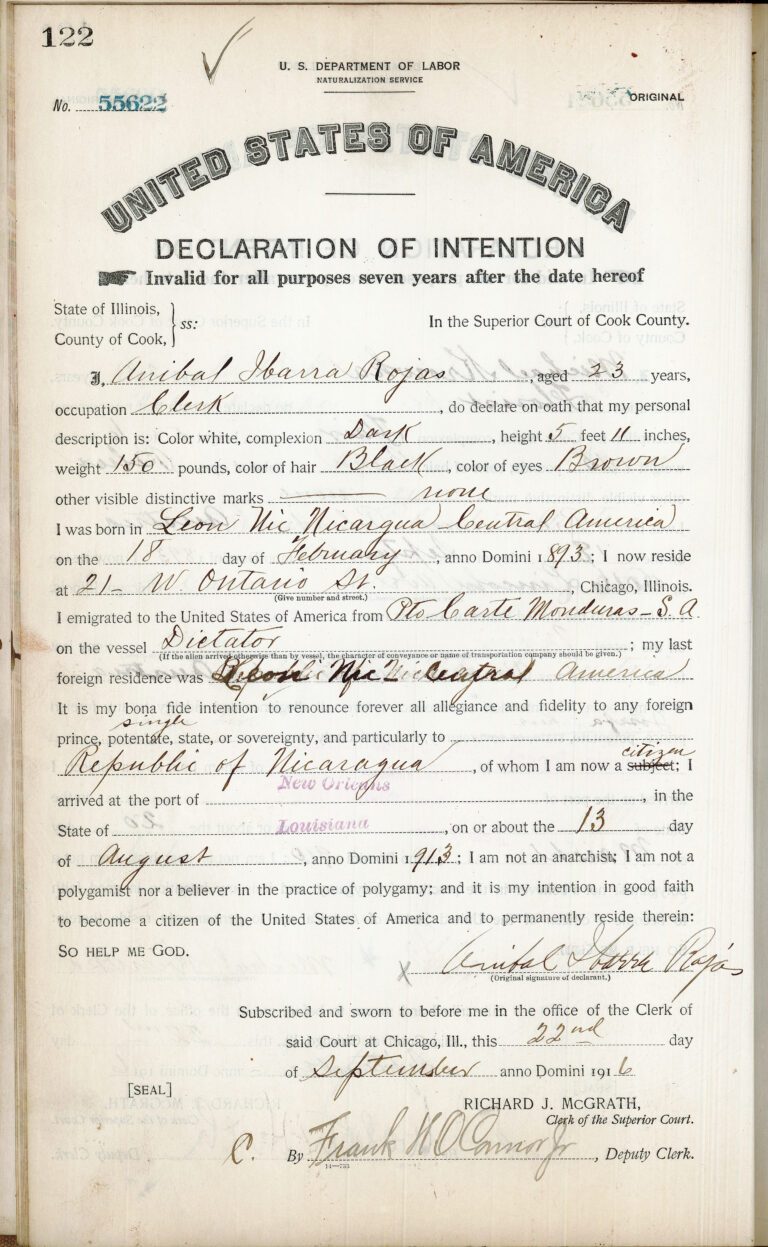

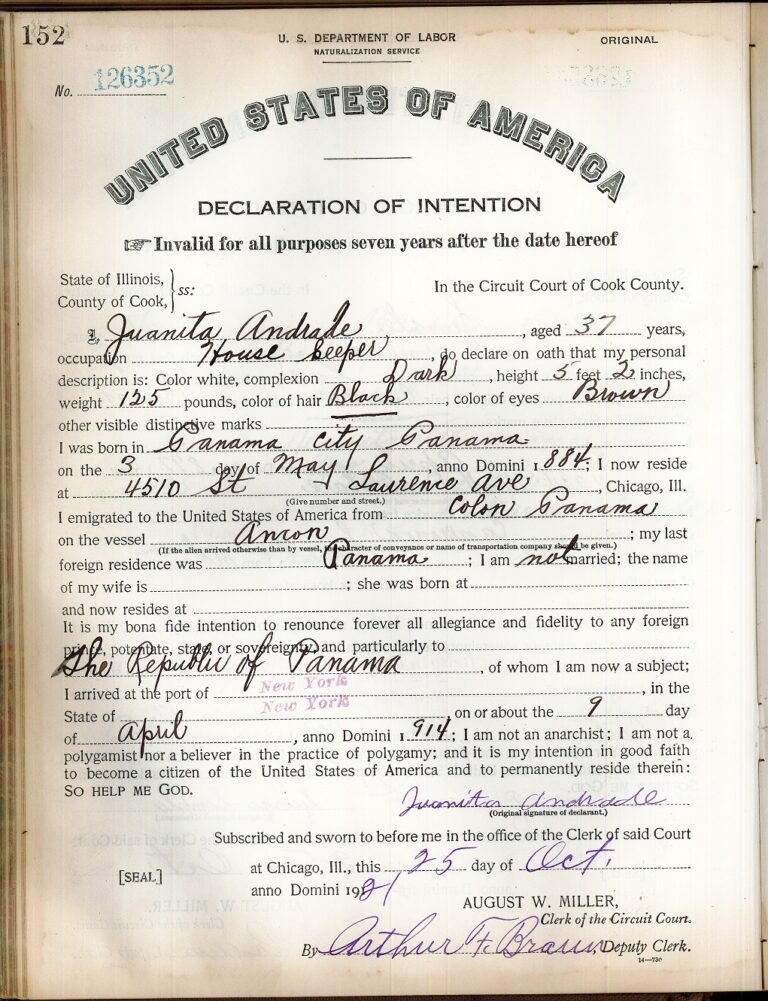

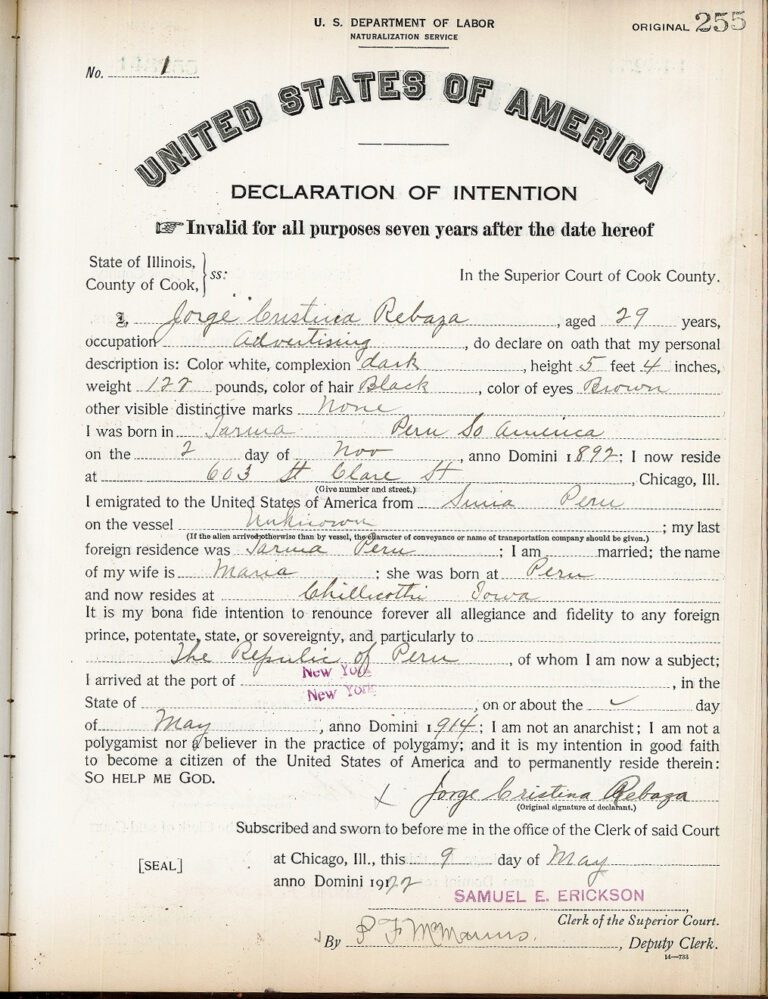

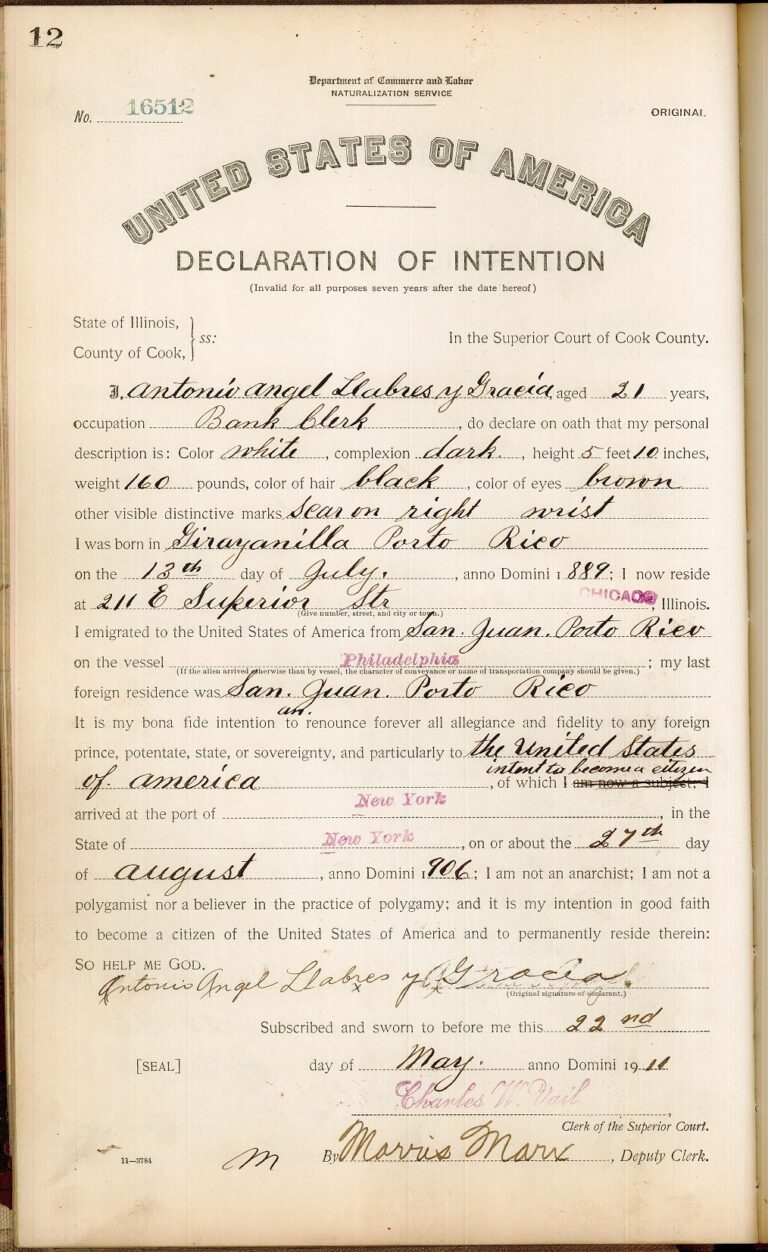

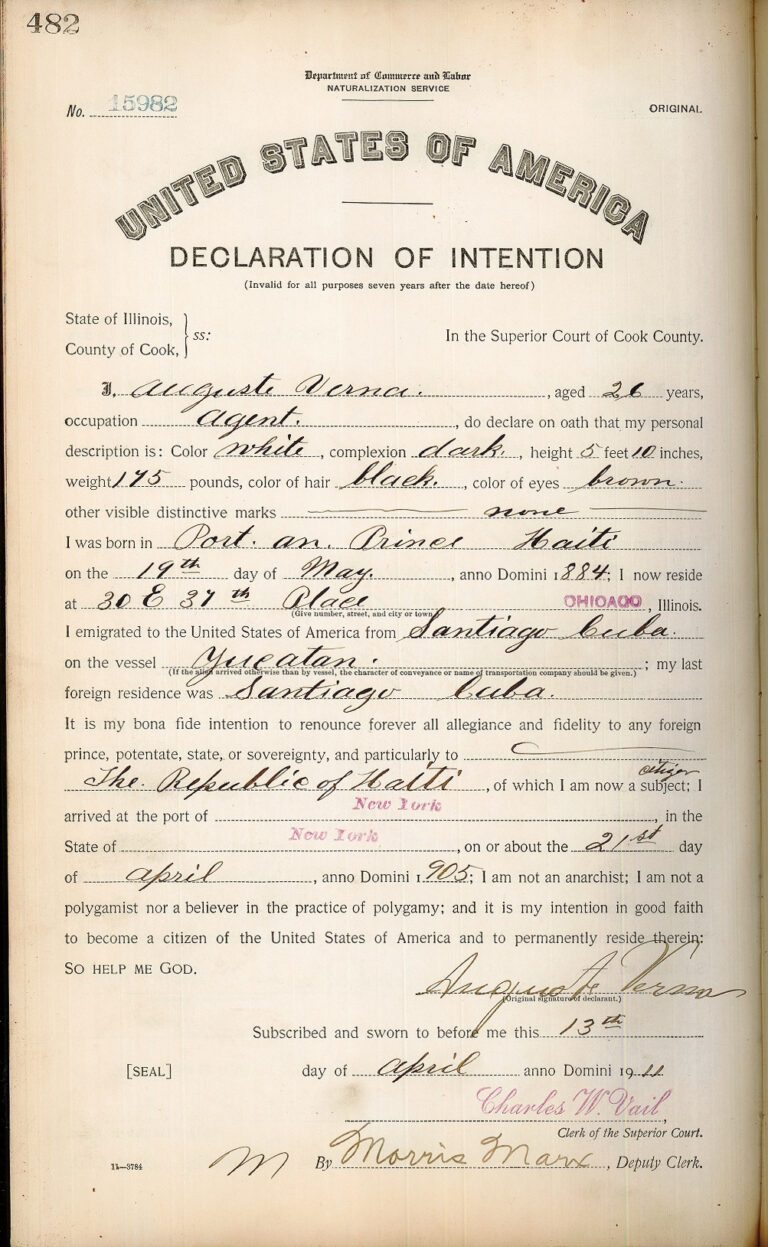

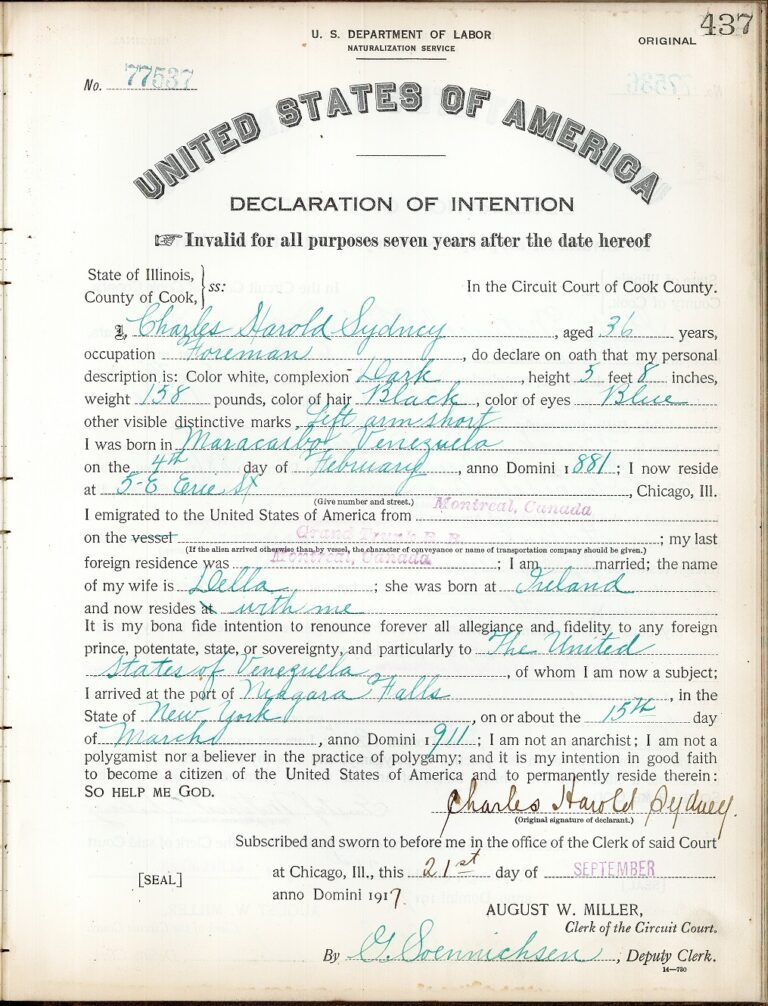

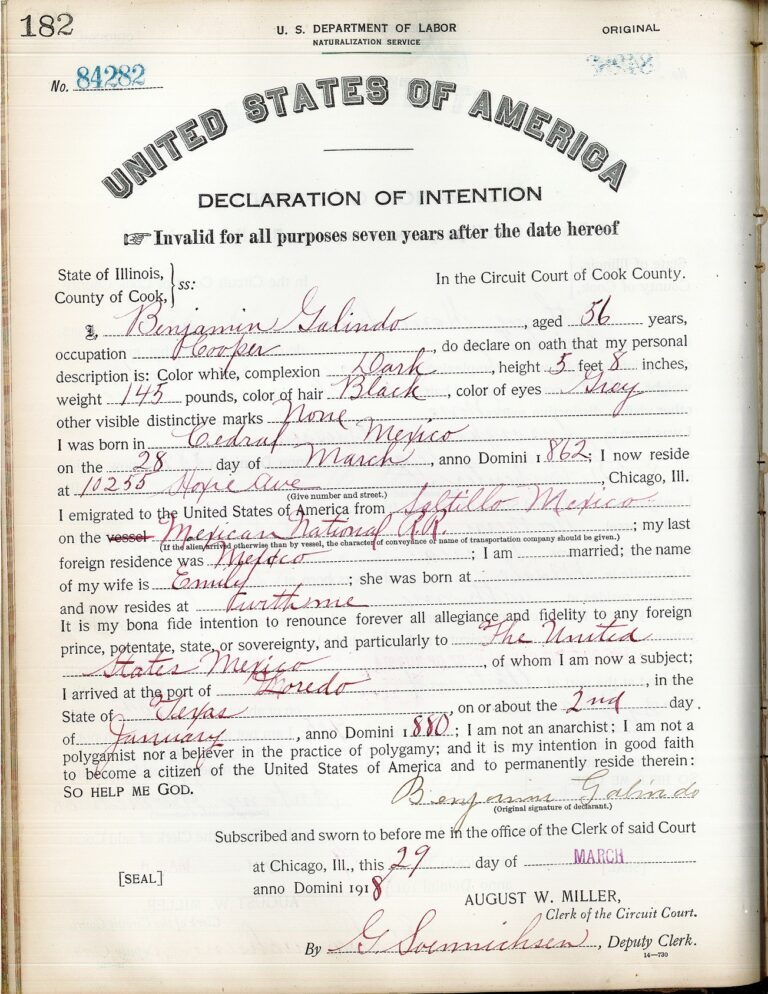

Naturalization Certificates / Certificados de naturalización

Naturalization certificates (reproductions), large-format

Naturalization certificates (reproductions), large-format

Archives of the Circuit Court of Cook County

Courtesy of the Archives of the Circuit Court of Cook County

Fredrich N. Belfort, an engineer from Argentina, 1907

Wilfred Laures Felise, a tailor from Belize, 1924

Iesabel Costello, a coppersmith from Brazil, 1888

Ladislao Castillo, a stenographer from Bolivia, 1917

Manfredo Augosto Ahumada, a clerk from Chile, 1920

Antonio Jobon, an electrical engineer from Colombia, 1916

Gonzalo Valinzuelis from Costa Rica, 1903

Eva Carrera, a homemaker from Cuba, 1909

Andres Pena, a laborer from Honduras, 1922

Anibal Ibarra Rojas, a clerk from Nicaragua, 1913

Juanita Andrade, a housekeeper from Panama, 1914

Jorge Cristina Rabaza, an advertizer from Peru, 1922

Antonio Angel Llabres y Gracia, bank teller from Puerto Rico, 1906

Louis Garcia, a machinist from Uruguay, 1917

Frederick William Ellis Sambias, a physician and surgeon from the Dominican Republic, 1917

Manuel Argudin, a factory worker from Ecuador, 1925

Jose Ramon Zarate, a chemist from El Salvador, 1919

Agosto Verna, an agent from Haiti, 1911

Charles Harold Sydney, a foreman from Venezuela, 1911

Benjamin Galindo, a cooper from Mexico, 1918

Maria Mangual in conversation / Maria Mangual habla

Maria Mangual in conversation with Board members, 1998

Maria Mangual in conversation with Board members, 1998

Audio recording

Courtesy of Mujeres Latinas en Acción. Recording donated to Mujeres by Doris Salomón (Board Chair, 1998-2001)

(Run time: 2:16)

Transcript

“My version is that it was 1970—it was really 1972, 1971—and there was a group of us that were working in different community organizations in the Pilsen community. And some of us were professionals, some of us were finishing up our degrees. And it’s like Laura said, we looked around and all of us were working in organizations that were basically run by men that had a focus to deliver services to men, and that’s where services in Pilsen were.

Except for El Hogar de Nino, which was run by a non-Latina, there was no organization that was headed up by a Latina in the community. And we said, what’s wrong with this picture? Because we were the ones who were doing all the work, and these guys were making all the decisions.

And so, you know what was happening in the early ‘70s too. It was the beginning of the feminist movement. There was really, the country was coming out of Vietnam. So there was a lot of change in the air. And a lot of can-do sort of spirit in the air. There was also the Brown Berets were coming in and organizing out of California. The Farm Workers were organizing out of California. People were saying it’s time for a change.

So, we got swept up in the moment of that decade and started trying to do what was considered almost the impossible, which was to organize women in a community to, in fact, have a woman’s organization, raise funds to provide services for women by Latinas, and to do it in a bilingual, culturally sensitive environment.”

Interview with Reyna Matoaka Ortiz

Interview with Reyna Matoaka Ortiz (excerpt), 2022

Interview with Reyna Matoaka Ortiz (excerpt), 2022

Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, CHM

Courtesy of Reyna Ortiz

(Run time: 1:22)

Transcript

“Well, it’s a huge part of my life because when it comes to being Two-spirited and having the ability to tell my family as a child that I wasn’t just a boy, and I wasn’t just a girl. And I came to these conclusions very young in my age, and luckily my parents had the general understanding about pre-colonial indigenous life where Native Americans had multiple gender identities.

So, when I came to my family as a child and I was having terrible, terrible issues about my gender identity, it was our connection to being indigenous and is where my mother was like, ‘Oh people like you have been around for thousands and thousands of years. And we acknowledge it and we accept it and we love it. I can’t tell you that the rest of the community is going to be so accepting.’

So, I give the fact that we were Indigenous—we are indigenous—is what kind of saved me from being outed or kicked out from my family. And all those kinds of religious persecution-type issues were gone because my parents understood that people like me existed for thousands and thousands of years.”

Interview with Anton Miglietta / Entrevista con Anton Miglietta

Interview with Anton Miglietta (excerpt), 2023

Interview with Anton Miglietta (excerpt), 2023

Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, CHM

Courtesy of Anton Miglietta

(Run time: 1:56)

Transcript

“…as we were doing this from that debriefing with students to then like, “Oh, my God, why don’t we just do it?” And then as we did it and had this meeting it could evolve into that hope that now we can actually impact this institution that has been so exclusive.

And I think it really does represent the spirit of a relevant and meaningful educational process that unfolded and that students really rose to the challenge. I think it’s exciting to see. And I think it is also hopefully, just the beginning of looking at how institutions—museums, in particular—decide on and develop their content, but just as big.

Hopefully this leads to the curricular and learning—for lack of a better term—renaissance in Latinx history, Latinx literature, media, because students are really dying for it.

Literally, it kind of feels like they feel it’s a sort of form of intellectual genocide—although they didn’t know that term.

But when they heard they term they felt like this was like, wow, to not be able to name one woman in Latinx history, and really only a couple males, is like a mental genocide in a way, like this is beginning to smash.

So, I just can’t wait to help build and be a part of building the curriculum for this exhibit and all of the materials and getting it out to, hopefully, hundreds of thousands of young people.”

“The American Hen” eggs / Huevos de “La gallina americana”

Puerto Rico: Puerto Ricans are US citizens even though Puerto Rico is not a state. Puerto Ricans can vote in presidential elections if they live in one of the 50 states, but their representative in Congress cannot vote. Although the US uses other terms (“commonwealth,” “unincorporated territory”), Puerto Rico is a colony. In 2024, Puerto Ricans on the island voted for the seventh time on whether they would like to become a state, become independent, or remain associated with the US in another way. Nearly 57% of Puerto Ricans preferred statehood. Nearly 31% preferred independence.

Puerto Rico: Puerto Ricans are US citizens even though Puerto Rico is not a state. Puerto Ricans can vote in presidential elections if they live in one of the 50 states, but their representative in Congress cannot vote. Although the US uses other terms (“commonwealth,” “unincorporated territory”), Puerto Rico is a colony. In 2024, Puerto Ricans on the island voted for the seventh time on whether they would like to become a state, become independent, or remain associated with the US in another way. Nearly 57% of Puerto Ricans preferred statehood. Nearly 31% preferred independence.

Cuba: The US claimed to be helping the Caribbean island gain independence from Spain, but then took Cuba as its own colony with the intention of supporting the US sugar industry. The US retained the power to intervene militarily whenever its economic interests were threatened. The US first exercised this “right” when it established the military base at Guantánamo Bay (1903). The detention center there (established in 2002 continues to hold prisoners illegally and indefinitely (in contradiction to US laws). Increasingly challenging conditions in Cuba have driven Cuban migration to the US.

The Philippines: The Philippines is a nation of 7,641 islands in Southeast Asia (not pictured on the map nearby). During nearly four centuries of colonization, the Spanish profoundly influenced everything from the name of the islands to the form of governance, economy, cuisine, agriculture, religion, social structure, and language. Filipinos were winning their independence from the Spanish when the US stepped in to “assist” with their revolution. Instead, the US took over colonial rule from Spain (1898). The Philippines gained independence in 1946.

Interview with Tania Córdova

Interview with Tania Córdova (excerpt), 2022

Interview with Tania Córdova (excerpt), 2022

Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, CHM

Courtesy of Tania Córdova

(Run Time: 3:44)

English Translation

I was very young; I was 15 when I came to Chicago. Ever since I was a little girl, I always knew who I was. To other people, I wasn’t normal, but in my world I’m normal. I was born a transgender woman and I’m going to die a transgender woman. People or my family never understood that and the bullying at school, at home, the rejection in society, in the town where I was born was very strong. I’m from Michoacán. And I’m from a very small village. And sexual harassment and rape were things that I had to deal with from a very young age. . .

Then, my arrival in Chicago. I remember, it was in winter, in January of ’85. And I looked for how… First of all, I was a 15-year-old person and now that I understand everything, I grew up very fast. At 15 years old, I was already an adult and I was already coming to work, going to help my parents, and that I stopped being a young person to become an adult who was going to have many responsibilities to support my family and get ahead. . .

Well, I think from the moment I decided first, to seek my happiness, which is one of the rights that every human being has, between the ages of 15, 16 and 18, I was navigating with a lot of frustrations because I didn’t know how to express myself and I didn’t have any support in any way. I finally found a group of friends who were in the same situation. And they began to tell me that there was a community that was mostly homosexual, and they started to take me places until I got to one of the historical sites which is La Cueva in the Little Village. . .

La Cueva was a bar that was called the key club. Only people who had a key could enter. That was before I came to the scene at this club. And there were transgender women who were already making history and were helping us as mentors so that we had an opportunity to express ourselves in a safe place.

In La Cueva it was to arrive and be yourself. Reach out and express yourself. And apart from expressing yourself and being in a safe place, it was also expressing art. La Cueva is known because it always had entertainment from transgender people imitating artists and I was also one of the people who went through that stage.

Interview with Adriana Portillo-Bartow / Entrevista con Adriana Portillo-Bartow

Interview with Adriana Portillo-Bartow

Interview with Adriana Portillo-Bartow

Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, CHM, 2012

Courtesy of Adriana Portillo-Bartow

(Run time: 1:46)

Transcript

APB: And when I met Michael McConnell, because I was a member of the National Council of the Sanctuary Movement, Michael, you know, too, that’s when I met him, in one of those gatherings. Michael told me that there was a synagogue in Chicago that was looking for a refugee, but they didn’t want the typical refugee that is dependent, you know, of them, and that they had to give them rights, and you know, all of that. That what they offered, because one of my frustrations was that I had to clean houses during the day, and had no time to do what I needed to do, which was human rights work, and denounce what had happened to my family, and you know, what was happening in Guatemala, and what, you know, the government, the militaries were doing, and the role the United States was playing, and all of that, you know?

And he told me about KAM [Isaiah Israel synagogue] and he told me that’s exactly the kind of refugee that they want. And so, when he came, he talked to them, and they said, “Well, that’s exactly the kind of refugee we want, and it’s like a marriage, you know, made in heaven for us.” So, we came, and he followed me, he came with me. And for a while, they provided us with an apartment, a monthly allowance, a school for my daughters, medical care, everything that we needed. And the way I was paying them back was the human rights work.

Int: Oh, okay.

APB: Which is what they wanted.

Interview with Elvira Arrellano / Entrevista con Elvira Arrellano

Interview with Elvira Arellano at Adalberto United Methodist Church

Interview with Elvira Arellano at Adalberto United Methodist Church

Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, CHM, 2022

Courtesy of Elvira Arellano

(Run time: 2:16)

English Translation

“And when my time for deportation came, I resisted and spoke to my pastor and told him, “I remember the sanctuary movement of the eighties, when Salvadorans and Central Americans were coming to the United States to seek refuge. And that many churches opened sanctuary for them.”

So, I talked to my pastor, and I told him, why wouldn’t the church be a sanctuary for me, so that I wouldn’t be deported? I thought that it’d be something like, I go to the church and stay there.

But we never imagined how big it was going to be. I didn’t have a vision that, oh, this whole street is going to be filled with media vans, or this church is going to be filled with reporters, or the church is going to become a TV studio for interviews for major shows. Not really, we didn’t know what was going to happen. And it was that, instead of turning myself over to immigration, I came to my church and my pastor declared the church a sanctuary for me.

It was a global bombshell that a woman dared to take sanctuary. But only by trusting in God. I’m a very religious person, I believe in God.

And I said, how can it be possible that this nation is doing all this against our families, when all we’re doing is looking for jobs and a better way of life.”

Future Homes artists / Artistas de Hogares futuros

Future Homes, 2016–17

Future Homes, 2016–17

Terracotta. Students of Benito Juarez Community Academy, Nicole Marroquin and Paulina Camacho Valencia, Teaching artists, United States

Gift of Nicole Marroquin and Paulina Camacho Valencia

Left Case

| Joselyn Salgado | America Vilchis |

| Evelyn Rivera | Nancy Ivsquiano |

| Pedro Guzman | Ximena Arroyo |

| Laura Vargas | Melissa Medina |

| Christian Resendiz | Saul Peralta |

| Moises Zavala | Miguel Martinez Nava |

| Daisy Moncines | Julissa Guillen-Barron |

| Diego Seruin | Leslie Cordoba |

| Elvis Gonzalez | Guadalupe Chiquito |

| Marcela Crisantos | Destiny Gutierrez |

| Jennifer Suarez | Estela A. |

| Michelle Andrade | Melina Cerero |

| Tony Tan | Melina Medina |

| Victor Carvajal | Jennifer Gallegos |

| Yazmin Jimenez | Marlene Paredes |

| Elena Cerero | Melissa Silva |

| Bryan Mendoza | Melissa Madrigal |

| Yolati T. | Daniel L. |

| Yesenia Rodriguez | Mark Cantu |

| Michelle Morales | Evelyn |

| Rolando F. | Irvin Ibarra |

| Nancy Sandoval | Ernesto Soto |

| Brandon Samano | Ivana Chairez |

| Giselle Andrade | Angel Perez |

| Ernesto Perez | Raul Gonzalez |

| Alonso Montona | Gelxi Ventura |

| Esmeraldo H. | Sofia Reno |

| Angeres Rangel | Abel Torres |

| Lexus M. Resendiz | Naylei Ortega |

| Kelse Campbell | Jennifer Reyes-Zepeda |

| Jose M. Mancines | Sculptor not recorded (15 sculptures) |

Center Case

| Yoalixi Melendez | Sara Silva |

| Cynthia Romero | Neftali Ortiz |

| Angel Perez | Daniel Salazar |

| Reyes M. | Caine Sigala |

| David Alberto | Uziel Pinarrieta |

| Grecia Salgado | Michelle Sandoval (2 sculptures) |

| Esmeralda Ambriz | Leila Villegas |

| Leslie Vargas | Jenny Flores |

| Marisol Landa | Jorge Estrella |

| Marisol Angel | Abigail Estrada |

| Norberto Reyes | Benito Martinez |

| Denise Metina | Noel Martinez |

| Margarita Mora | Maria Hernandez |

| Nayeli De Leon | Leo Garcia |

| Thebe Neruda | Anette Pardina |

| Omar Cardona | Luis Garcia |

| Beatriz Munoz | Cesar Muñoz |

| Elizabeth Lopez | Alexis Bustos |

| Deisy Uriostegui | Arleth Castañeda |

| Jocelyn Capetilla | Darla Torres |

| Johanna Priego | Evelyn Ramirez |

| John Yomandro | Jocelyn Ontiveros |

| Fatima S. | Reyes and Medina |

| Maria Zuniga | Ezequiel |

| Fernanda Rea | Alexandra Godoy |

| Jose L. | Sculptor not recorded (46 sculptures) |

| Emily Lopez |

Right Case

| Giselle Andrade | Yesenia Viveros Barrera |

| Grecia Salgado | Ari Andrade |

| Kenosha Simmons | Sergio Rentenia |

| Anette Pardina | Andrea Zaragoza |

| Paula Dominguez | Alonso Montoya |

| Ramon Perez | Georgina Quintana |

| Joanna Salgado | Jocelyn Ontiveros |

| Kennia Ruiz | Citalli Vergara |

| Ximena Galindo | Dinah Towns-Wright |

| Alexis Zambrano | Rosangela P. |

| Jennifer Castaneda | Diana Sanchez |

| Paula Guitierez | Raul S. |

| Erica L. | Joanna Salgado |

| Jonathan Martinez | Melissa Silva |

| Adinelba Guillen | Christian Resendiz |

| Denise Munoz | Lilyann Hernandez |

| Nataly H. | Maria Siynla |

| Esmeralda Ambriz | Dontell Cheers |

| Valeria Mata | Jailene Delgado |

| Cesar Ortiz | Ashley Martinez |

| Alicia Becerra | Jasmin Martinez |

| Miranda F. | Alyra O. |

| Vivian Oronia | Jacky Hernandez |

| Jazmin Patino | Ismael Andrade |

| Jorge Sotelo | Denisse Brito |

| Roberto Ortega | Ezequiel |

| Jose B. | Vianey V. |

| Gerado Garcia | Adilene Manzo |

| Aysha Salamen | Ulysses Tapia |

| Evengelina Garcia | Armando Barbosa |

| Michelle Sandoval | Sculptor not recorded (29 sculptures) |

Interview with Josue Siu / Entrevista con Josue Siu

Audio interview with Josue Siu (excerpt), 2023

Audio interview with Josue Siu (excerpt), 2023

Studs Terkel Center for Oral History, CHM

Courtesy of Josue Siu

(Run time: 1:08)

Transcript

“And that’s the changes that we’ve seen in the neighborhood. Families moving out of the neighborhood and then we have new families—they’re probably not accustomed to the ice cream guy. And, again, with the new model of business that is in the area, which is just an ice cream shop—a storefront—it’s a different—they did not involve, or they’re not expecting the ice cream guy, I’m sure.

I remember when I was a kid and I remember the ice cream guy. And that was when I came into this country. What was it? 1996? And I remember. I remember the guys. And I wasn’t accustomed to the ice cream guys, but I remember them passing by and I was excited just to hear the bells, and we would just go outside.

I mean, who that lives in Chicago doesn’t know the bell for the paleta—and for the corn guy?

Two different things and you know who is which. And even for the ice cream truck. You know which one is the ice cream truck. So, you know the song, so you kind of wait for them. And that’s how my guys are.”