Latest Posts

The Chicago History Museum is here to support families during these uncertain times. We know that especially now, it is more vital than ever that we stay connected with one another and with our communities. We also know that you have a lot on your plate, answering your kids’ questions, filling their time, and supporting their remote learning.

We’re excited to announce that our CHM at Home initiative kicks off next week! Our Education team will be sharing free, family-friendly activities every weekday. These history challenges are easy to do and use everyday household items. You can get your child started independently or you can explore together. All of our activities promote learning of Chicago history, help make personal connections with the city, encourage family conversation, and foster creativity. The daily challenges will also be posted on our website, so you can do them anytime.

Feel free to share your creations with us using the hashtag #CHMatHomeFamilies on social media, so we can create a digital community that showcases what we love about Chicago and celebrates families and communities across the city. We hope you enjoy these at-home history challenges and your time together. We look forward to hearing from you!

CHM assistant curator Brittany Hutchinson recounts the life of Mary Koga. This blog post is part of a series in which we share the stories of local women who made history in recognition of our online experience: Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.

“My lens is attracted to people and their inner strengths and support systems.”

—Mary Koga

Mary Koga was a photographer and social worker, known for her work documenting first-generation Japanese immigrants and working to promote cultural exchange between Japanese and US communities in Chicago and beyond.

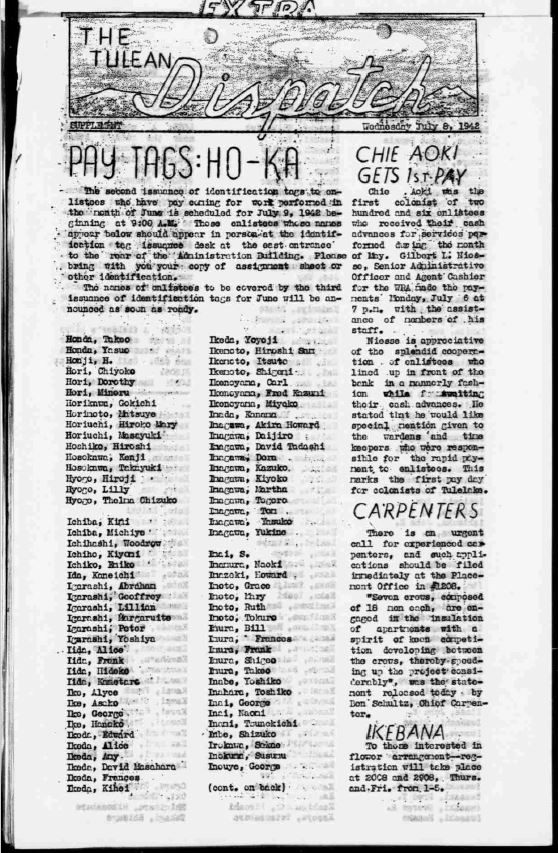

An undated photograph of Mary Koga. Courtesy of the Japan America Society of Chicago

Koga was born Hisako Ishii in Sacramento, California, on August 10, 1920. After graduating from the University of California, Berkeley in 1942, she was incarcerated at the Tule Lake Segregation Center in Tulelake, California. Tule Lake was the largest of ten internment camps operated by the War Relocation Authority during WWII and the last to close, remaining in operation until May 5, 1946. This experience affected Koga’s work throughout her life, including her interest in communal living and her strong sense of duty to others.

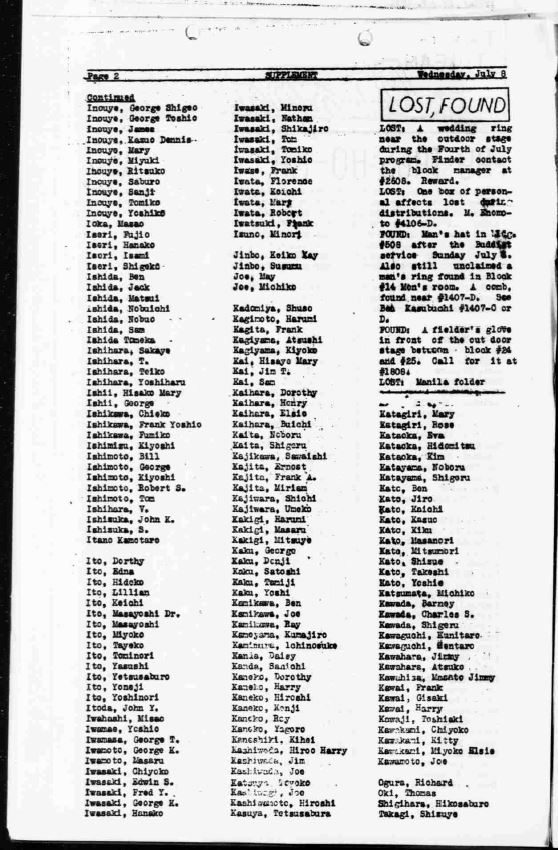

Koga is listed as “Ishii, Hisako Mary” in this group of “enlistees” being issued new identification at the Tule Lake internment camp, The Tulean Dispatch, 1942. Library of Congress, sn84025953

Following her release, Koga relocated to Chicago where she pursued a career in social work. In 1947, she completed her master’s degree in social work from the University of Chicago and worked in the field for twenty years before earning her photography MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

As a social worker in the 1950s and ’60s, Koga did casework at the Family Service Bureau, United Charities of Chicago; Northwestern University Medical School; and the Institute for Juvenile Research. She was also an assistant professor for field work at the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration from 1960 to 1969.

Koga received her first camera as a child and remained fascinated by photography throughout her life. She did much of her photographic work in the late 1960s and ’70s, including a one-woman show at the Chicago Public Library’s Rogers Park Branch in 1968. During her career as a professional photographer, Koga was also a professor of photography at Columbia College Chicago.

Koga’s photography ranged from floral forms to portraits of Hutterites, a communal branch of Anabaptists living primarily in Western Canada and the upper Great Plains of the US. In the 1980s, Koga documented the Issei, or first-generation Japanese immigrant community (see slideshow below). In one series of photos, Koga captured approximately 100 individuals with an average age of 76 at the Adult Day Care and Senior Citizens Work Center at the Japanese American Service Committee in Chicago.

Dorothy Kaneko and her mother Masano Morita, November 1988. Photograph by Mary Koga. CHM, ICHi-176757

Koga’s close connection to the Japanese American community in Chicago was apparent through her work in reviving the Japan America Society of Chicago (JASC) in the 1950s. Today, the JASC is still actively fostering communication and cooperation between the US and Japan and supporting numerous business and cultural programs, as well as offering Japanese language courses.

When Koga died in 2001, her legacy continued with the Mary Koga Memorial Fund and the JASC’s Mary Koga Award.

The Japan America Society of Chicago will host its 90th anniversary gala later in 2020, which will include a first-time viewing of JASC’s collection of rare Japanese art, including the photography series, Floral Forms, by Mary Koga. To learn more about the Japan America Society visit www.jaschicago.org.

Further reading:

CHM curatorial intern Brigid Kennedy recounts the extraordinary life of Elizabeth Lindsay Davis. This blog post is part of a series in which we share the stories of local women who made history in recognition of our online experience: Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.

Elizabeth Lindsay Davis not only took the motto of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW)—“lifting as we climb”—as inspiration for the title of her book, she took it as her personal motto. As an historian, writer, and activist, Davis worked hard but never forgot to uplift the work of her companions and colleagues.

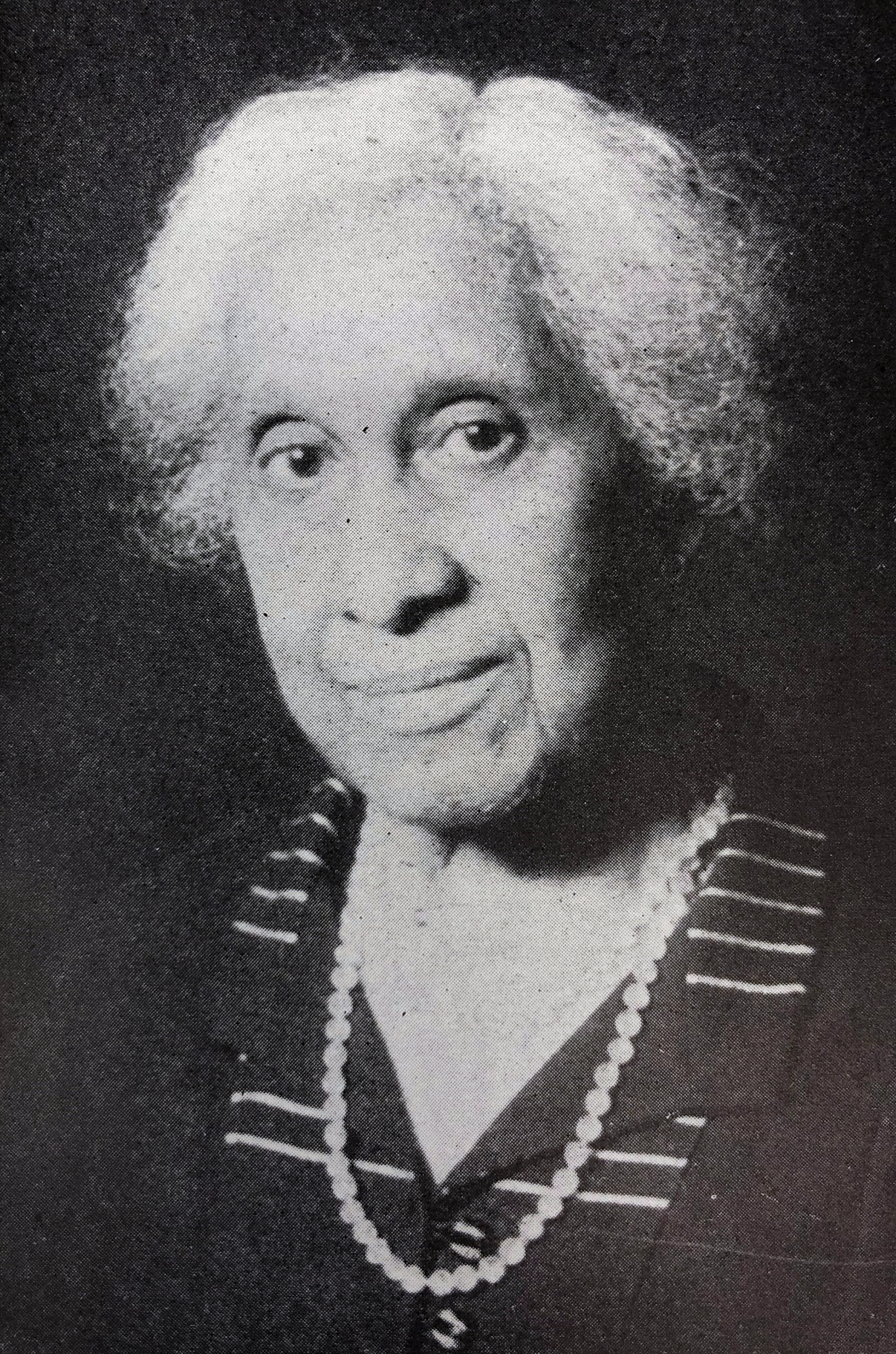

Portrait of Elizabeth Lindsay Davis, c. 1933. Lifting as They Climb, CHM

Davis was born in 1855 and lived her earliest years in Peoria, Illinois. As a young woman, she wrote advice columns that were published in Kansas City’s Gate City Press. Davis continued to write for newspapers, contributing regularly to the Chicago Defender and the NACW’s National Notes.

Davis began her career as a teacher, working around the Midwest until her 1885 marriage to podiatrist William H. Davis. In the next decade, she became active in the women’s club circuit, joining and founding organizations advocating for black women. A founding member of the Ida B. Wells Club, Davis served as secretary while Wells herself served as president. Davis also cofounded the Chicago branch of the Phyllis Wheatley Club, which focused on hyperlocal issues to improve the lives of people in Chicago. She served as president for twenty-eight years.

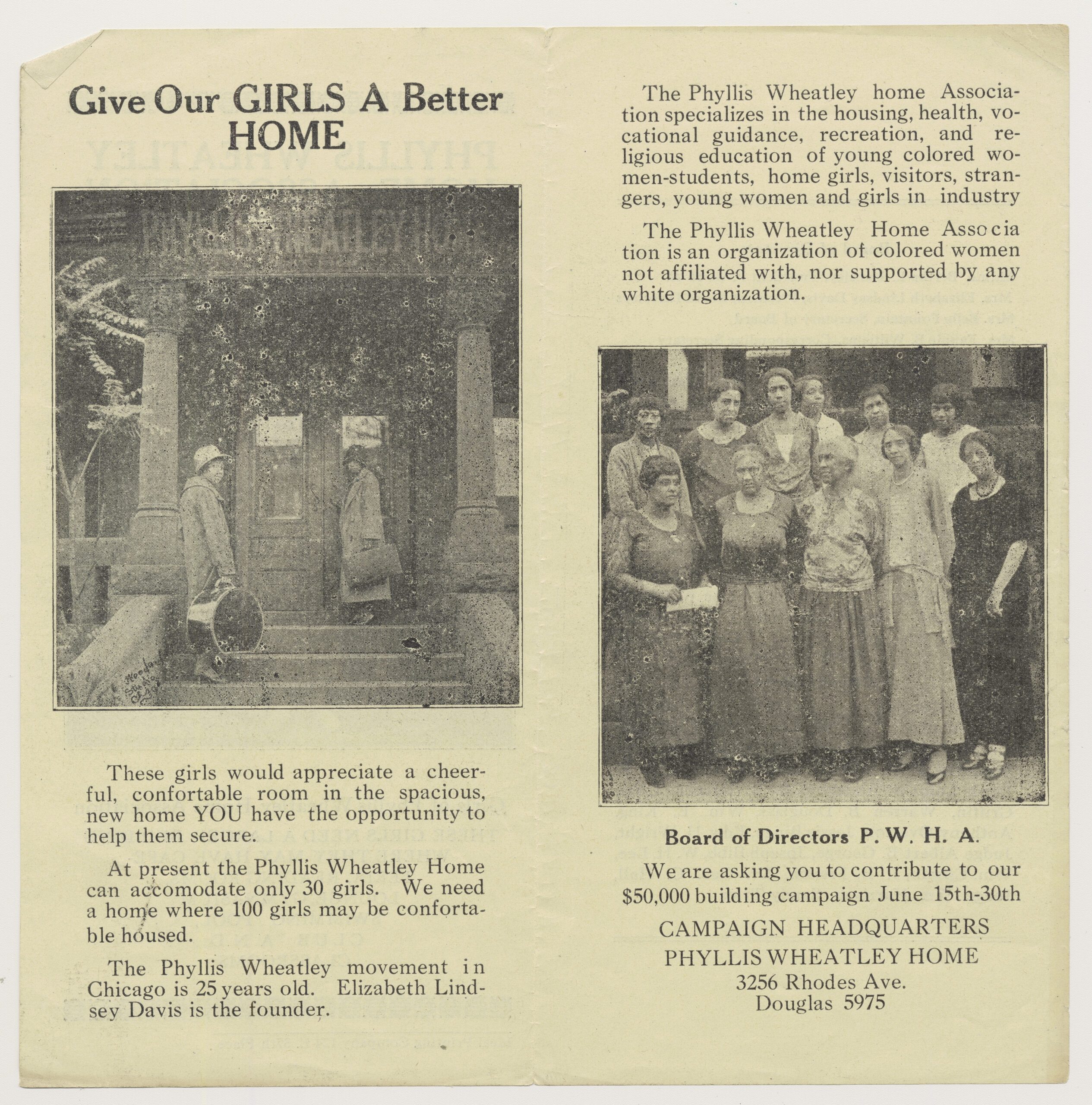

In 1899, the clubs of Illinois came together to form a coalition, the Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs (IFCWC)—the groups were collectively known as the “Magic Seven.” Davis was also affiliated with the NACW, for which she was the national organizer from 1901–6 and again from 1912–16, supervising the addition of more than 289 clubs. During this time, Davis saw how organizations such as the Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) failed to provide housing, health, and educational services for black girls and women, so in 1908 she founded the Phyllis Wheatley Home.

Phyllis Wheatley Home Association, pamphlet. 1915. ICHi-064245, CHM

As a leader of numerous groups, Davis knew more about the NACW and IFCWC than anyone else. She became the IFCWC’s official historian in 1918 and began work on The Story of the Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, 1900–1922. In 1933, for the A Century of Progress International Exposition, Davis published her book Lifting as They Climb—a history of the NACW, which she spent nearly a decade compiling.

During World War I, Davis led the Second Ward’s war office at the Frederick Douglass Center Women’s Club. There, women operated an exemption board for drafted men, a Red Cross auxiliary, and a post office. During the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic, the Frederick Douglass Center also served as a relief station.

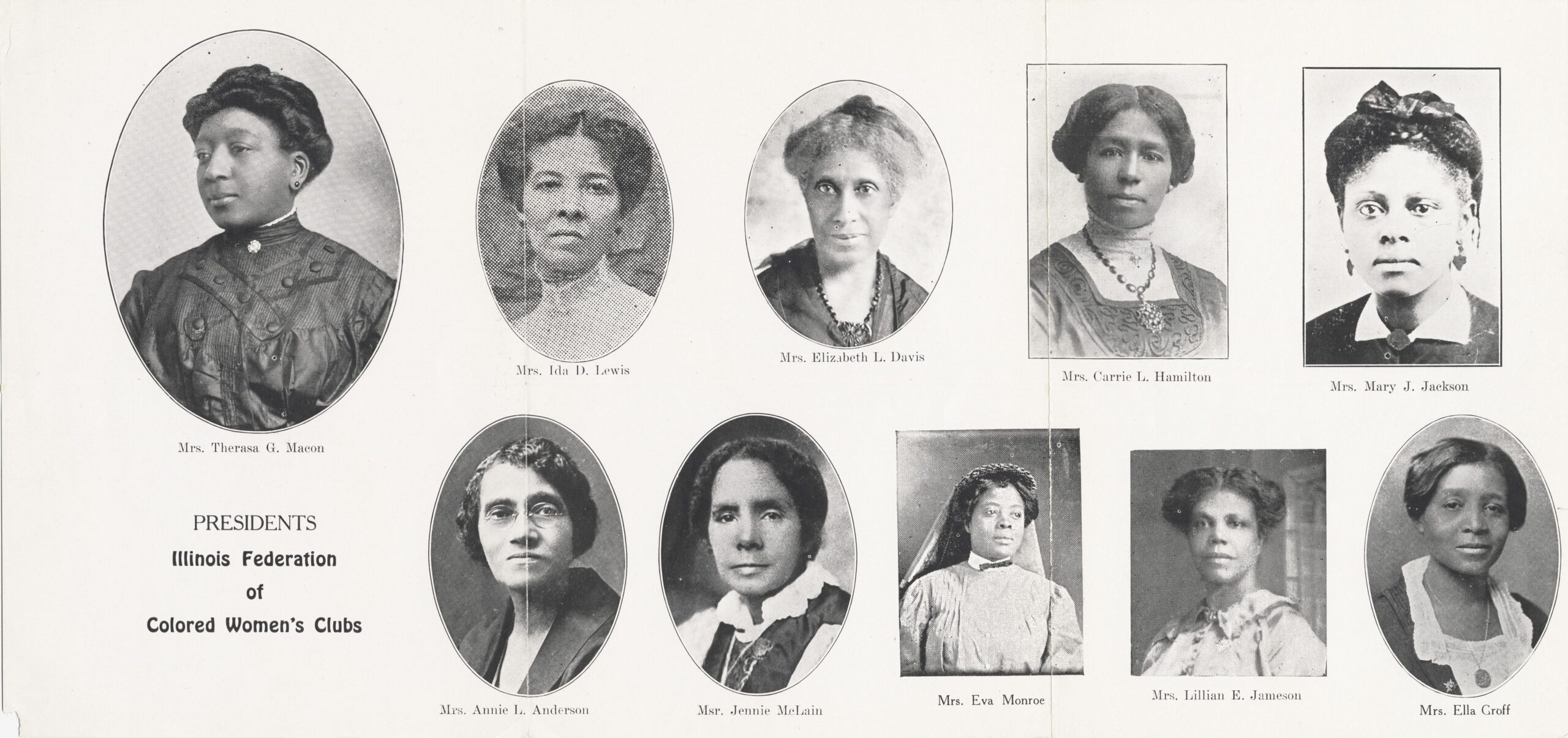

Presidents of the Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, from “The Story of the Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, 1900–1922.” Davis is in the top row, middle. 1922. ICHi-063063, CHM

When Illinois women gained limited suffrage in 1913, Davis was one of the first women to register to vote. She became increasingly active in politics and instituted citizenship classes for women through her clubs. Davis both celebrated the progress that had been made and devoted her life to equity and opportunities for black women. “To women has come the greatest opportunity through the passage of the 19th amendment,” she wrote in Lifting as They Climb. “It is fitting at this time that the Negro woman should take her part in the Century of Progress and prove to the world that she, too, is finding her place in the sun.”

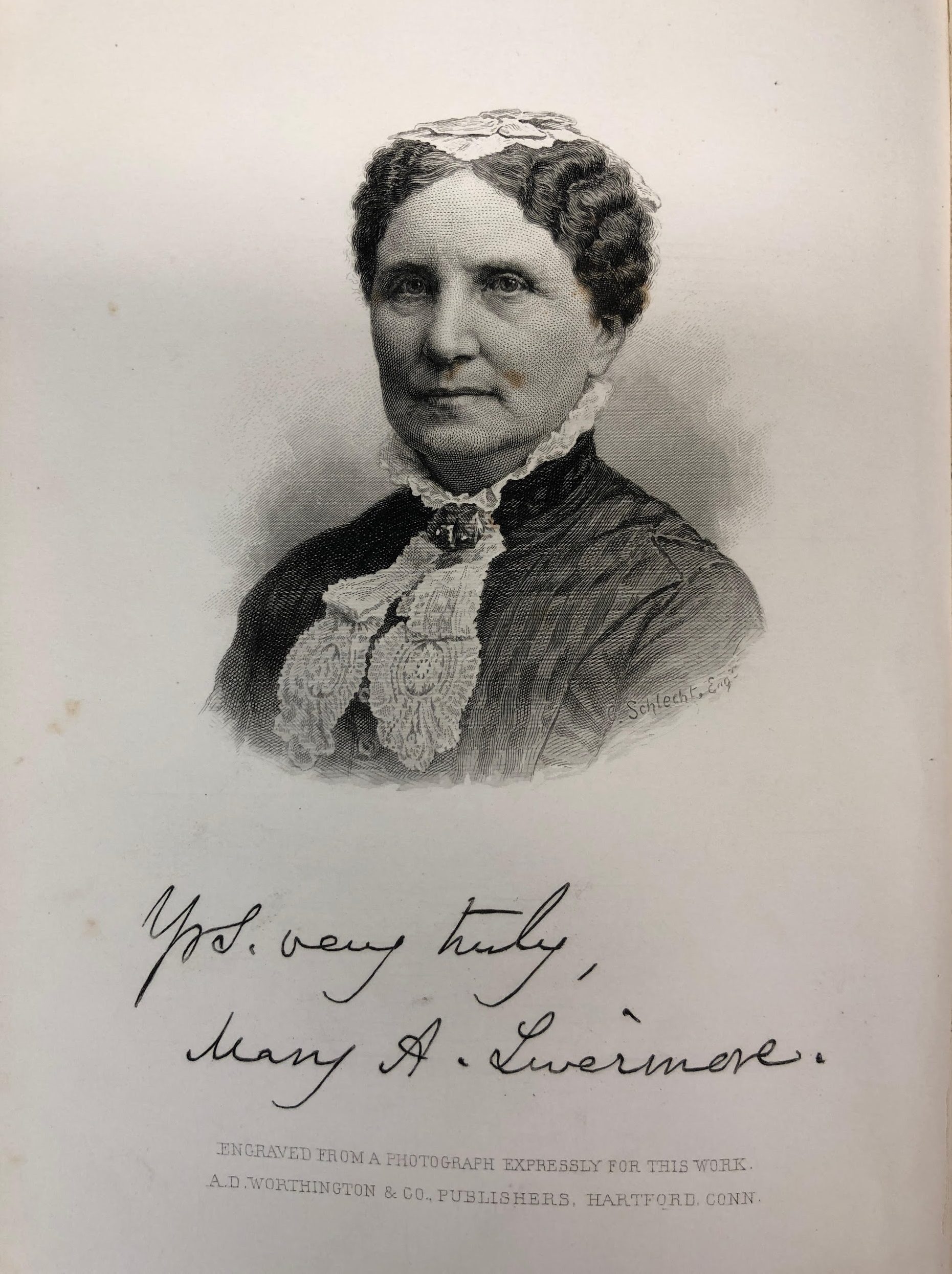

CHM curatorial intern Brigid Kennedy recounts the extraordinary life of Mary Livermore. This blog post is part of a series in which we share the stories of local women who made history in anticipation of CHM’s upcoming exhibition Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote.

Mary Livermore dedicated her life to abolition, temperance, women’s suffrage, and supporting the Union during the Civil War. Skilled in organizing, raising awareness, and gaining support for her causes, Livermore became a friend to Abraham Lincoln, a popular orator, and a key figure in the Union’s victory.

An undated portrait of Mary A. Livermore. ICHi-051132, CHM

Born in Boston on December 19, 1820, Livermore spent her early years there working in a secondary school—even editing a temperance newspaper for young people.

Livermore, her husband Daniel, and their family planned to move to Kansas in 1857 with other abolitionists, intending to secure Kansas as a free state. Before the move was complete, their daughter became sick and the family decided to settle in Chicago.

Livermore quickly established herself as a philanthropist in the rapidly growing city. She cofounded the Home for the Friendless, Home for Aged Women, and the Hospital for Women and Children in her first six years in the city. Then, the Civil War broke out.

In June 1861, it became clear that the Union Army was suffering more from illness and malnutrition than from Confederate weaponry, and Lincoln established the United States Sanitary Commission to centralize civilian relief efforts. A Chicago branch opened soon after, managed by Livermore and Jane Hoge. Livermore toured Union encampments and battlefront hospitals, delivering supplies, attending to the wounded, and bringing back news from the front.

In early 1863, Ulysses S. Grant praised the Sanitary Commission and credited them with saving many lives. Still, Grant’s needs were beyond what the Commission could provide as his army closed in on Vicksburg, Mississippi, and he requested more aid.

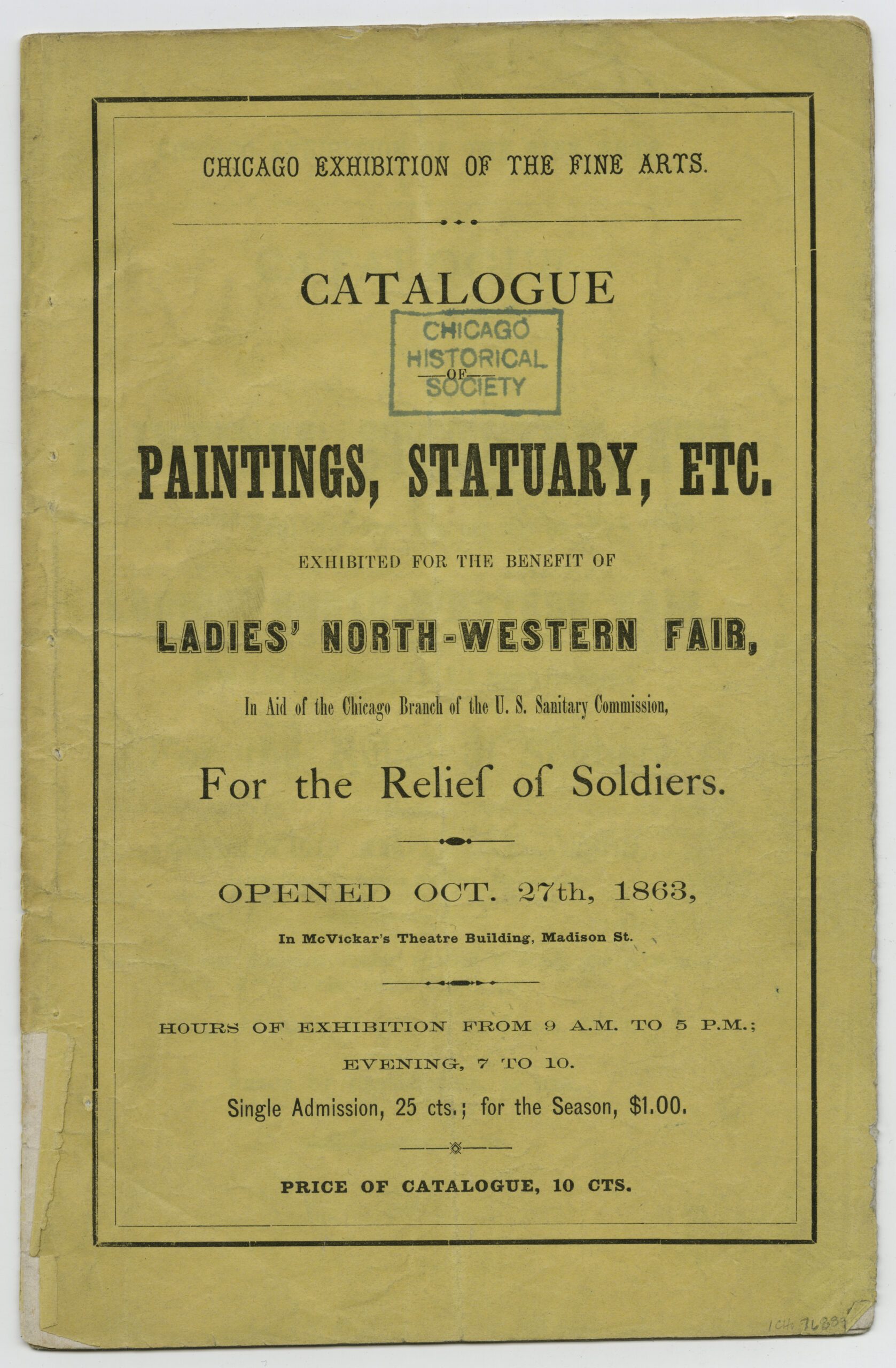

Front cover of Catalogue of Paintings, Statuary, Etc. exhibited for the benefit of the Great Northwestern Fair, 1863. ICHi-076889, CHM

Livermore and Hoge proposed a Great Northwestern Fair, where they could auction off or sell food, entertainment, and mementos of the war. They recruited thousands of volunteers, almost all women, to plan the event—the first of its kind.

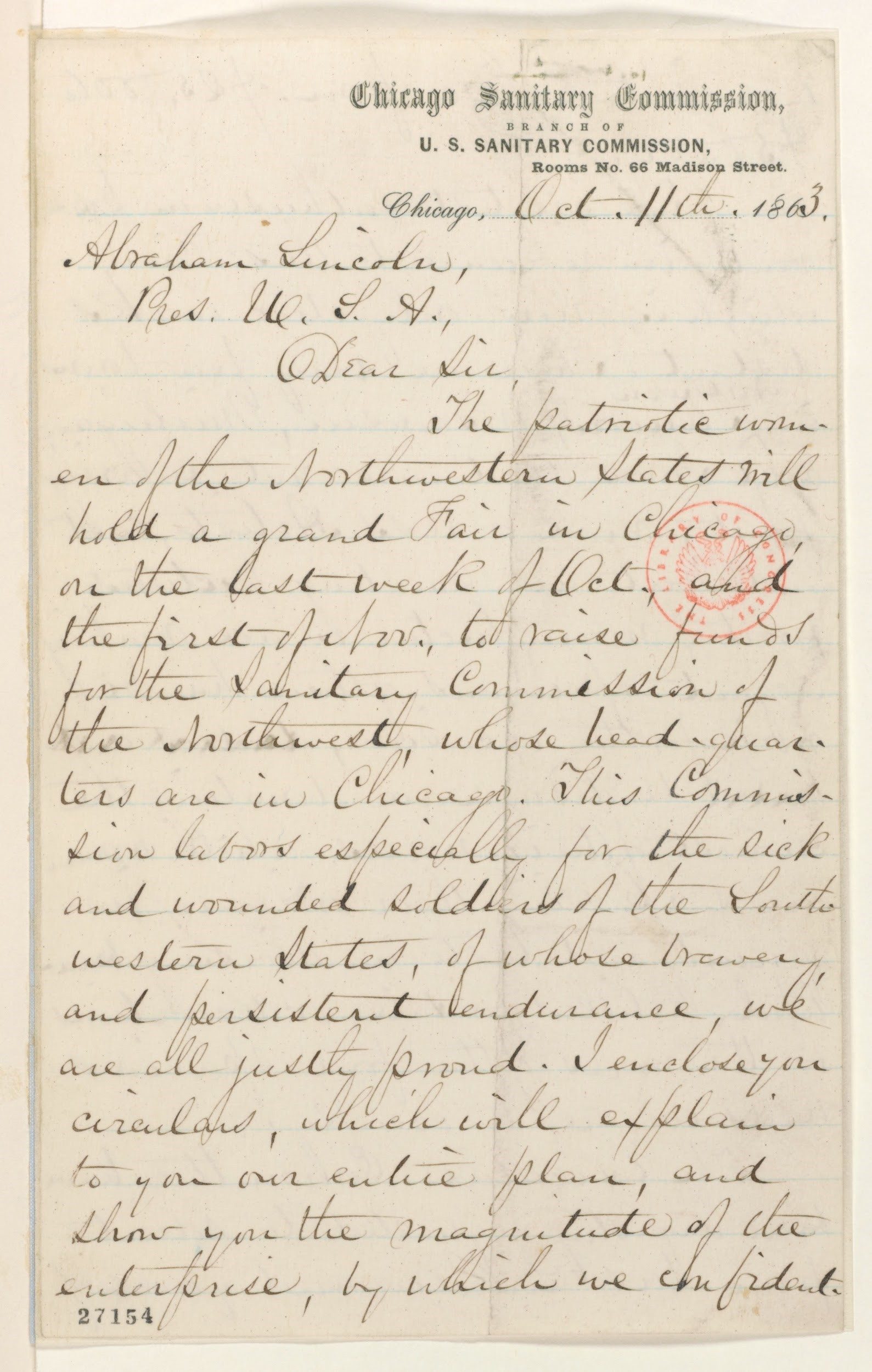

Livermore acquired war mementos for auction from across the Midwest, and even requested assistance from Abraham Lincoln, who donated the original Emancipation Proclamation. It sold for $10,000 and found a home at the Chicago Historical Society before being destroyed by the Great Fire in 1871.

On October 11, 1863, Livermore wrote to Lincoln requesting the original copy of the Emancipation Proclamation. Abraham Lincoln papers at the Library of Congress: series 1, General Correspondence 1833–1916.

The 1863 Great Northwestern Fair was a resounding success. Livermore had hoped to earn at least $25,000, and in the end, the Sanitary Commission made more than $86,000 from the estimated eighty-five to ninety thousand visitors. The fair fundraising model became popular, and soon similar events were held in other American cities.

Due to the success of the 1863 Great Northwestern Sanitary Fair, a second fair was held in 1865. ICHi-063123, CHM

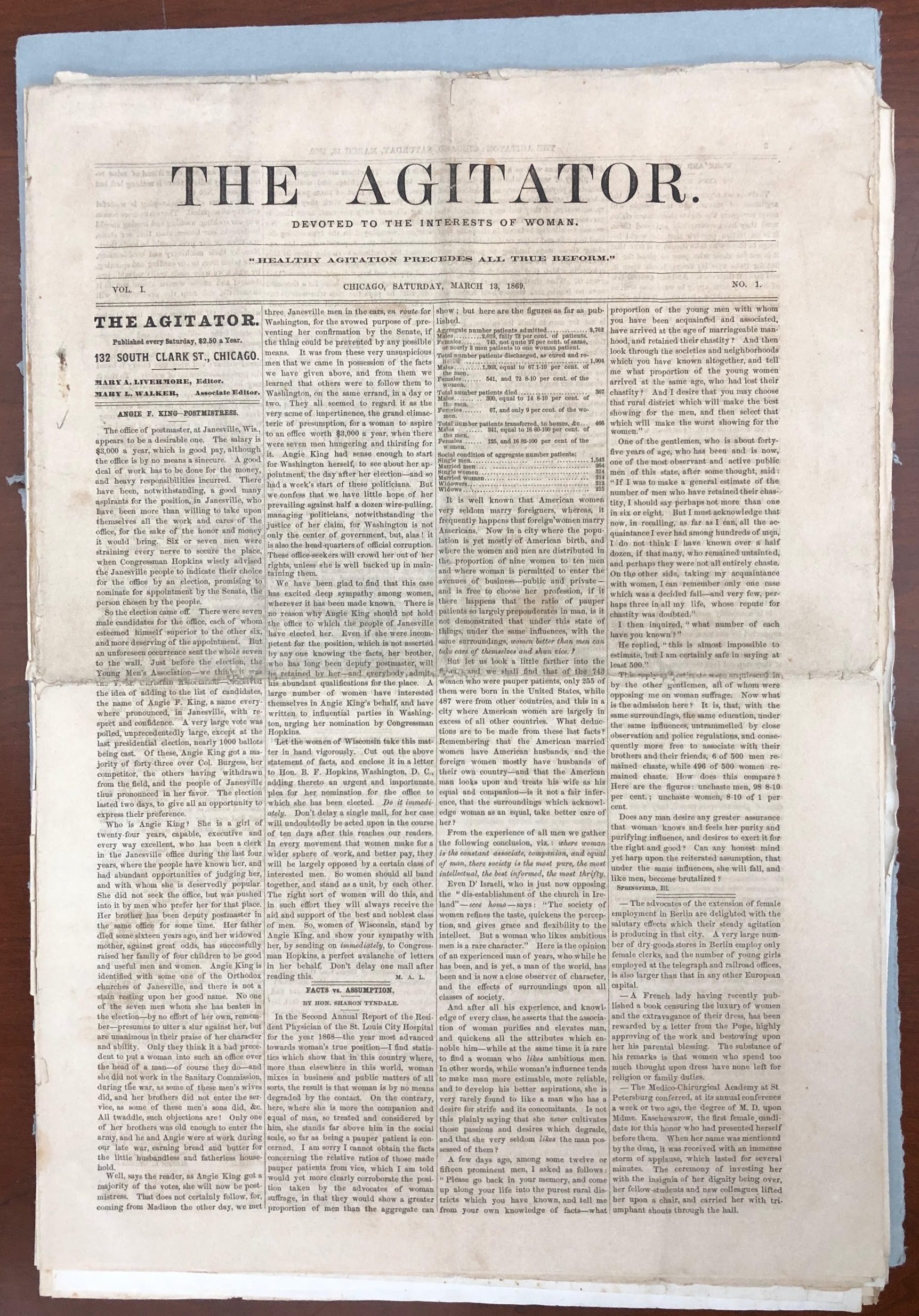

After the war, Livermore focused her energy on fighting for women’s suffrage. In 1869, she organized Chicago’s first suffrage convention and established The Agitator, a suffrage newspaper.

March 13, 1869, edition of The Agitator, with the subheading “Healthy agitation precedes all true reform.” The Agitator, CHM

In 1870, Livermore returned to Massachusetts, but continued her work in Chicago from afar. She traveled the country, lecturing on the history, lives, and experiences of women. She wrote two autobiographies and other texts supporting the rights of women.

An autographed page from one of Livermore’s autobiographies, “My Story of the War: A Woman’s Narrative of Four Years’ Personal Experience in the Sanitary Service of the Rebellion,” 1888. CHM

Although Mary Livermore didn’t plan to spend such a large portion of her life in Chicago, the life she built here not only made her instrumental to the Union war effort, but also made the day-to-day lives of many Chicagoans—especially women—safer through her philanthropic and activist work.

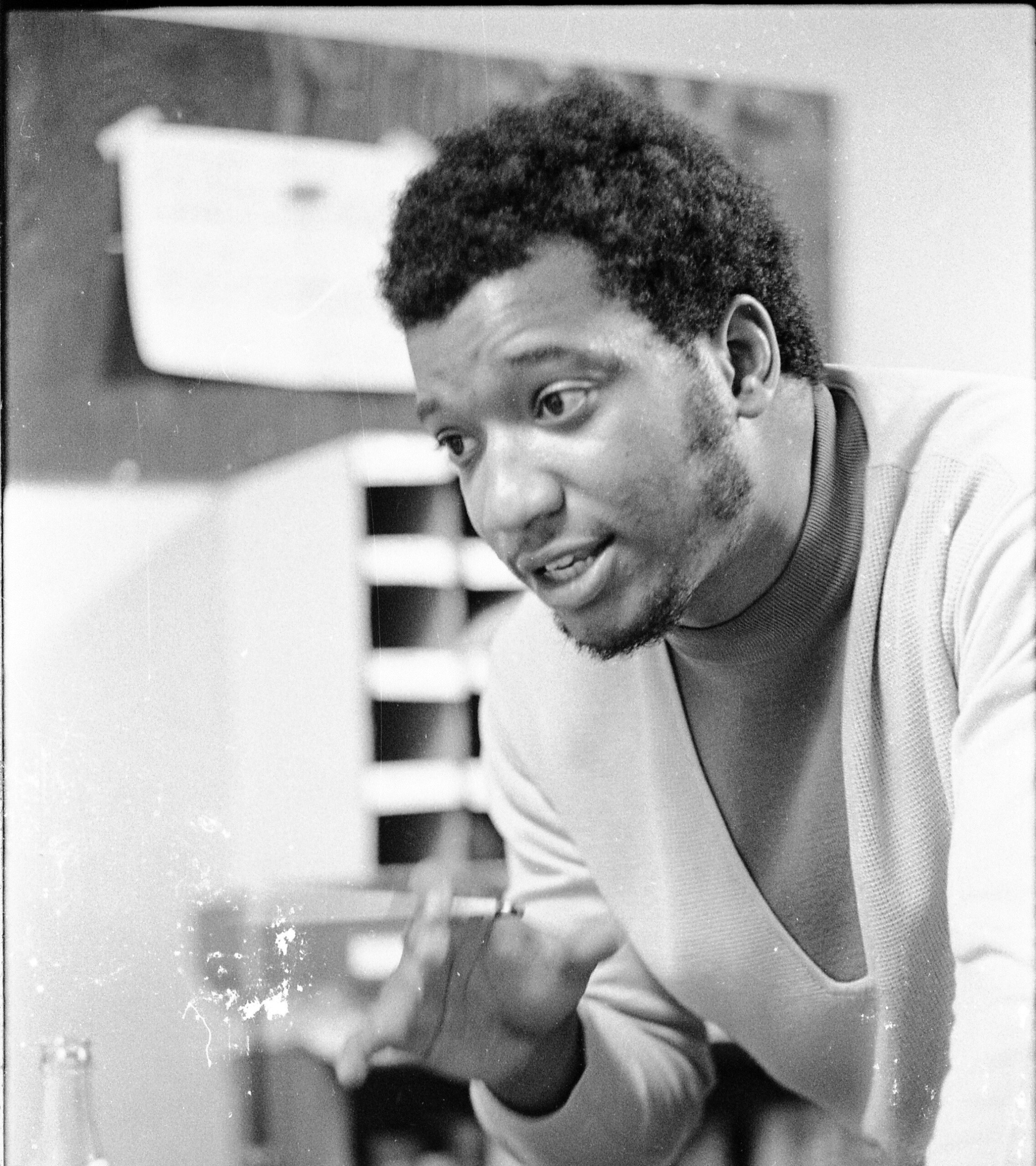

Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois Chapter of Black Panther Party, November 5, 1969. ST-17101234-0002

On the fiftieth anniversary of Fred Hampton’s murder, the Chicago History Museum remembers his life, tragic death, and legacy with an eye toward the future. In keeping with the Museum’s goal of sharing Chicago’s stories and educating the community, CHM assistant curator Julius L. Jones partnered with undergraduate research assistants from Lake Forest College to present The Assassination of Fred Hampton, a project through Digital Chicago.

- See more images of Fred Hampton’s life, death, and legacy

- Listen to an interview with Billy Ché, the deputy minister of education for the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party

All images from the Chicago History Museum’s Chicago Sun-Times collection

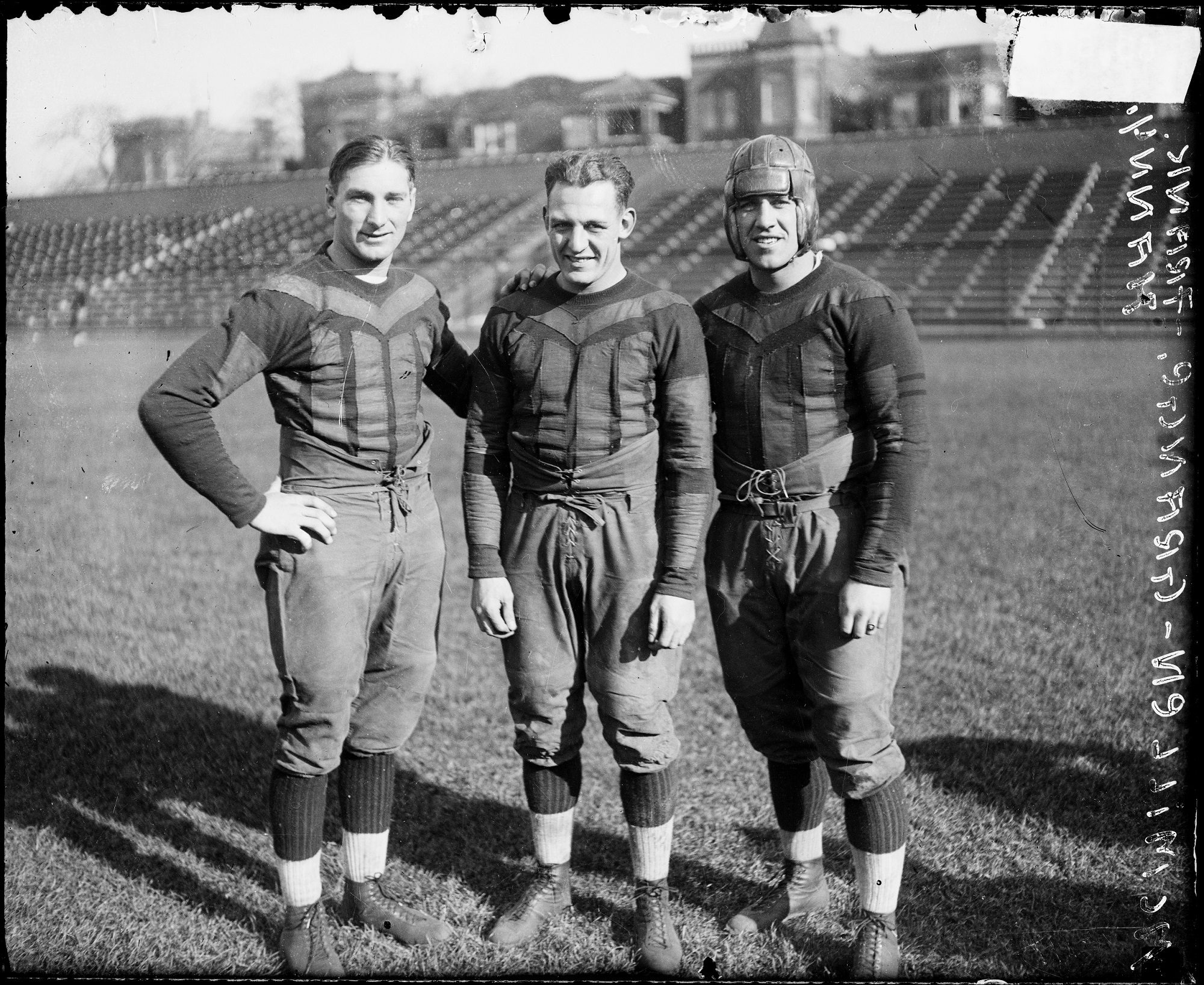

The 2019 National Football League season marks the centennial for both the league and a few original teams, including our very own Chicago Bears. To commemorate the occasion, assistant curator Julius L. Jones compiled some highlights from the Bears’ first century using artifacts and images in the Chicago History Museum’s collection.

The Chicago Bears began as the Decatur Staleys in 1920 as the charter franchise of the American Professional Football Association. The Staleys, an industrial team sponsored by the A. E. Staley Company, played in the central Illinois town of Decatur until moving to Chicago the following year and winning their first NFL Championship. In Chicago, the team adopted the nickname Bears in 1922 and took up residence at Weeghman Park, the home of the Chicago Cubs baseball team, which was renamed Wrigley Field in 1927. Chicago Bears players (from left) Frank Hanny, Harold “Red” Grange, and Jim McMillen at Weeghman Park, 1925. SDN-065677, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

An undated photograph of the Bears versus the San Francisco 49ers at Wrigley Field, the team’s home for fifty seasons. They moved to Soldier Field in 1971. CHM, ICHi-034862

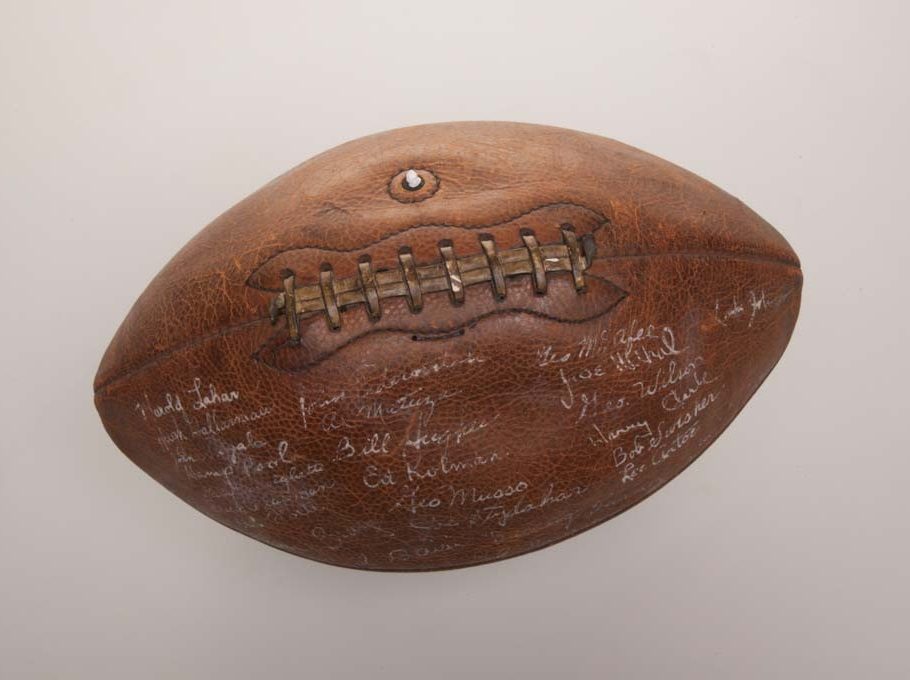

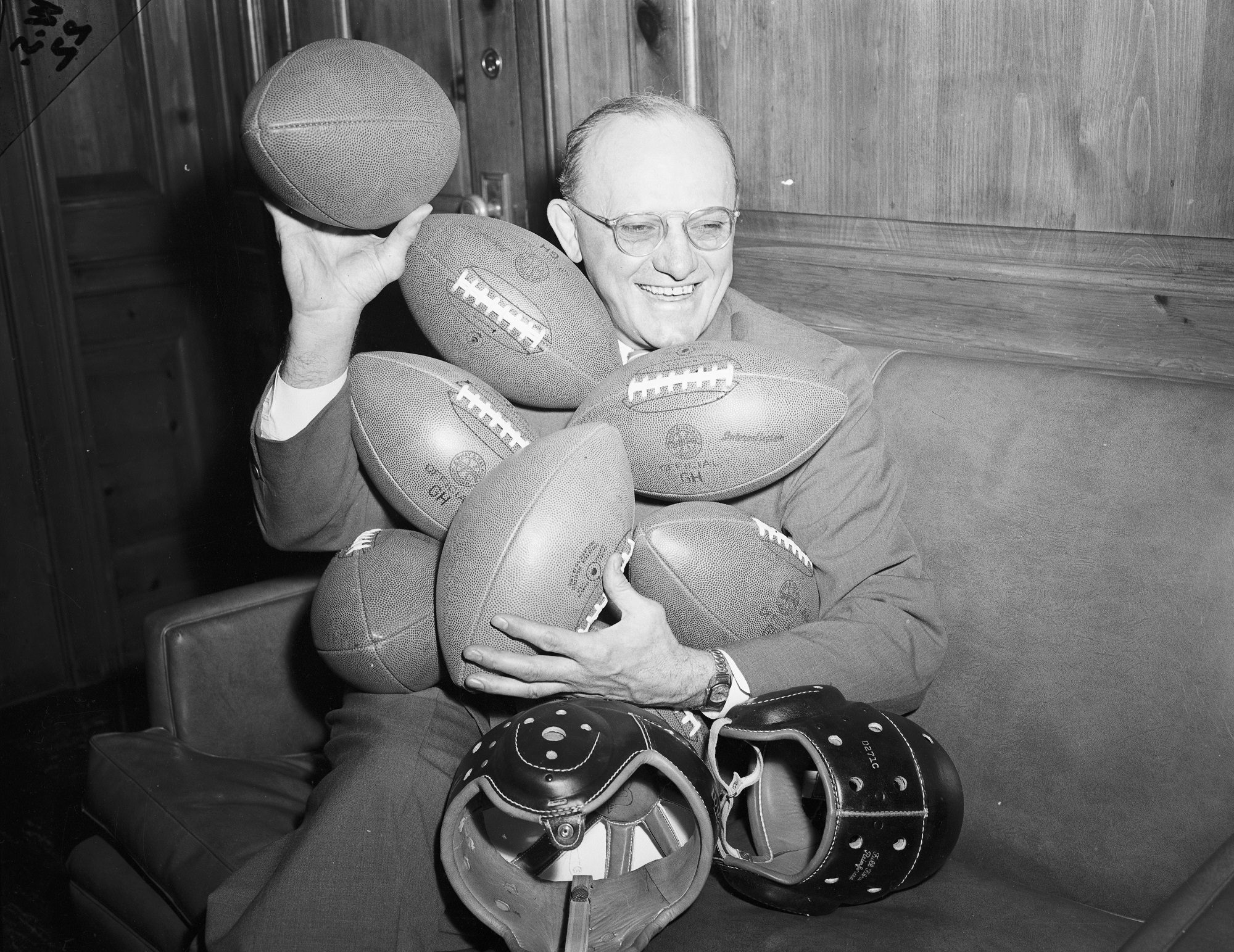

The Bears won the NFL championship again in 1932, 1933, and 1940. This football (CHM, 1968.985) was used in the 1940 NFL Championship Game in Washington, DC, on December 8, 1940, where the Bears beat the Washington Redskins 73–0. The score remains the most lopsided victory in NFL history. The Bears would go on to win in 1941, 1943, 1946, and 1963, bringing the team’s total championship wins to eight.

George Halas was not only the founder of the Chicago Bears, he was also a player (1920–1929) and served as coach (1920–67). Known as “Papa Bear,” Halas owned the team until his death in 1983, at which time his daughter, Virginia Halas McCaskey, succeeded him as owner, a position she still holds today. In the above photograph, Halas poses with an armful of footballs at the opening of a sporting goods store in Chicago, December 10, 1947. CHM, ICHi-065126

The Bears haven’t always been the only football team in town. They vied for fans with the Chicago Cardinals until 1959 when the Cardinals moved to St. Louis. This photograph was taken in November 1959 during the last crosstown matchup between the two teams. CHM, ICHi-22406; J. Johnson Jr., photographer

After their success in the 1940s, the Bears struggled, missing the playoffs from 1964 to 1976. In this photograph, Bears quarterback Rudy Bukich (#10) leads the team through practice at Wrigley Field, November 4, 1965. SDN-110001660023, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The team’s fortunes began to turn around when they drafted Walter Payton in 1975. In this undated photograph, Walter Payton breaks a tackle from the Green Bay Packers. CHM, ICHi-063777

During his thirteen-year career, Payton broke nearly every NFL rushing record and earned the nickname “Sweetness” for his unique running style and friendly personality. A nine-time Pro Bowl Selection and 1977 Most Valuable Player, Payton was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1993. Sadly, Payton died of a rare liver disease in 1999 at the age of forty-five. Tens of thousands of mourners packed into Soldier Field for his memorial service while millions more watched on television. Home jersey worn by no. 34 Walter Payton. CHM, ICHi-066522

This helmet was worn by Mike Singletary, who played linebacker for the Chicago Bears from 1981 to 1992. He was part of the Bears’ vaunted defensive line during his career and his play earned him induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1998. Bears helmet. CHM, 1986.178.1e

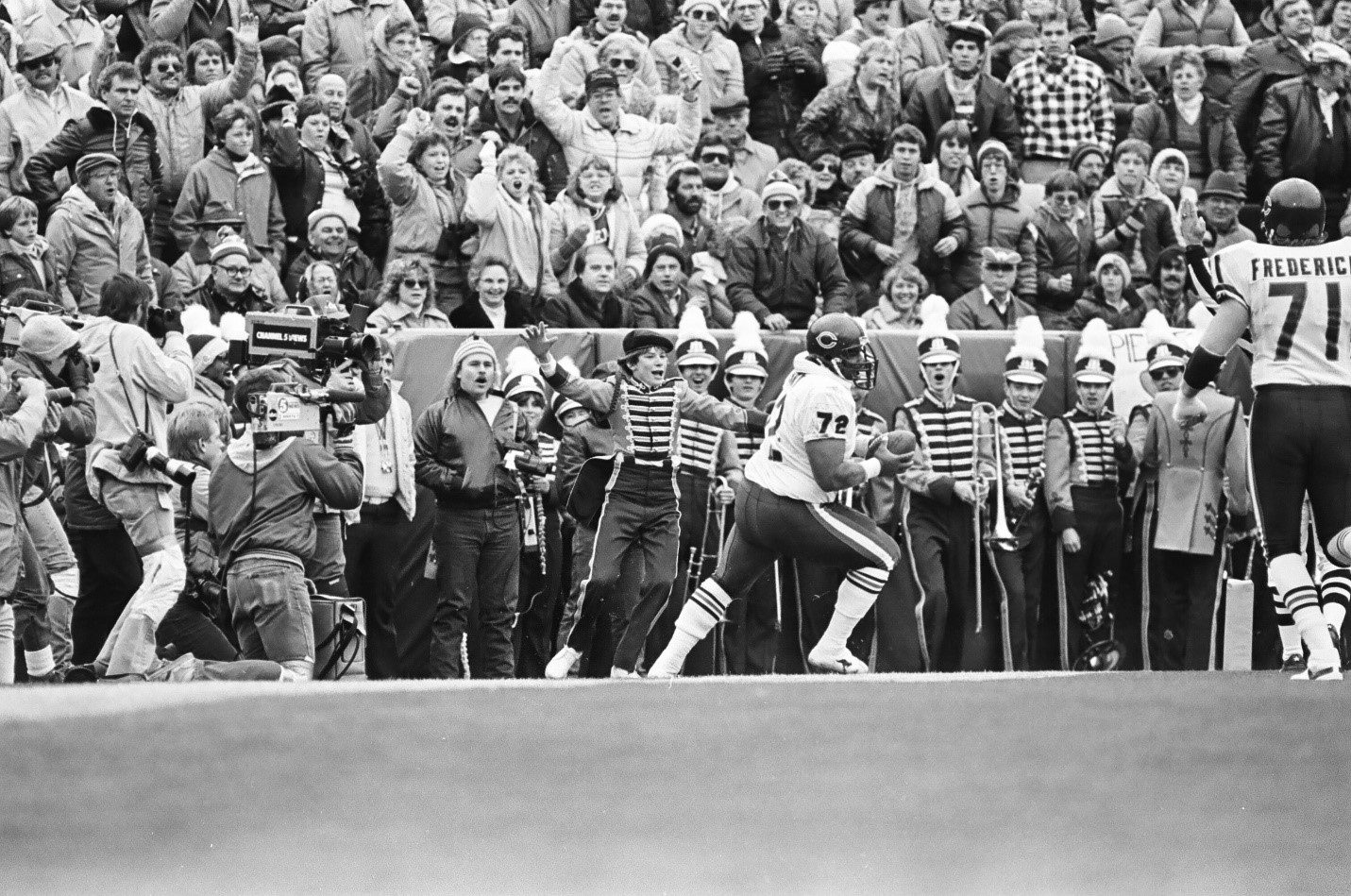

Defensive lineman William “The Refrigerator” Perry scored a touchdown against the Green Bay Packers on November 3, 1985. Due to his massive size, the Fridge was often called on the run to catch the ball when the Bears were near the goal line. SDN-500042200158, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

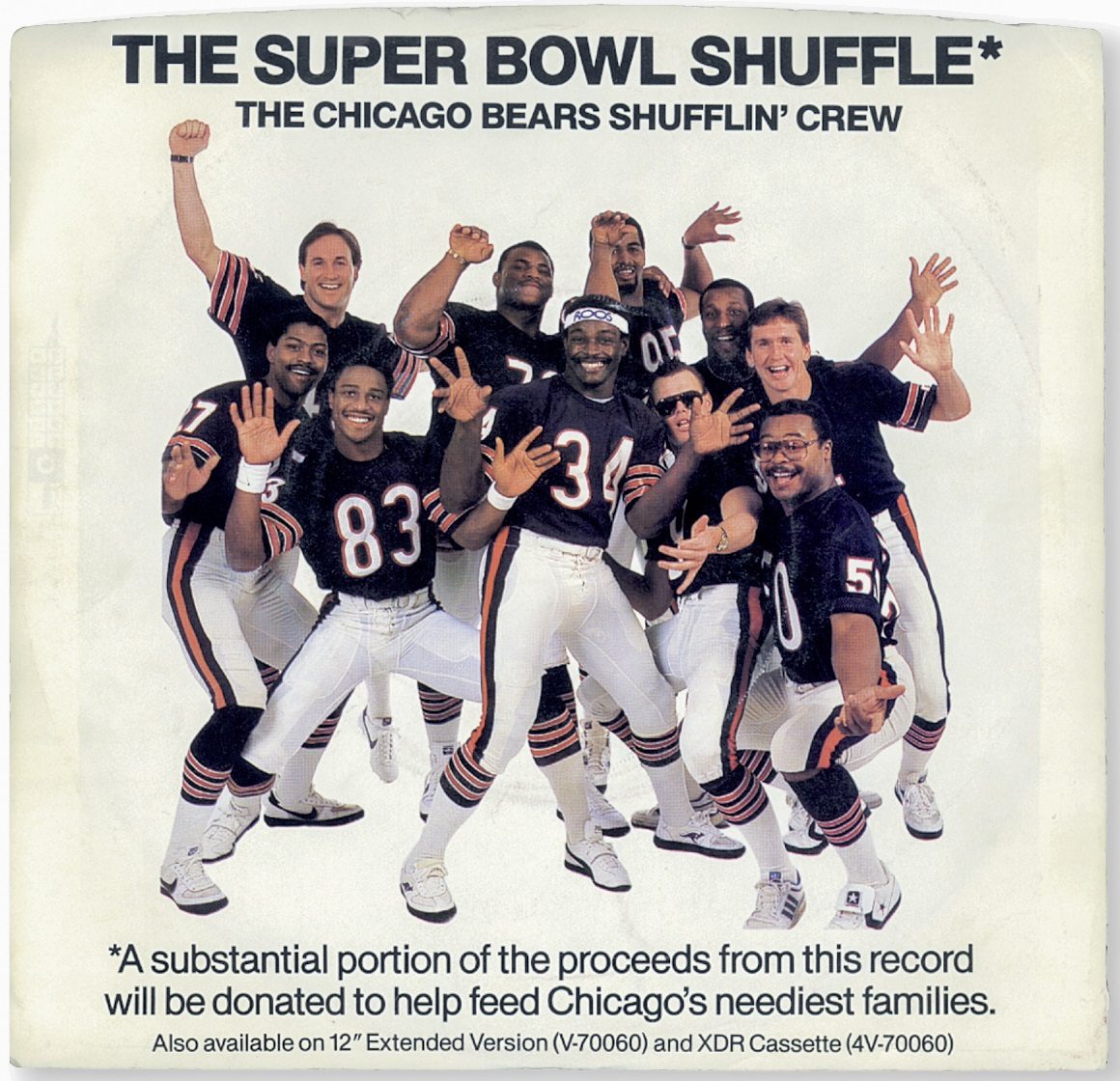

The Bears’ 1985 season and its players are legendary: they set a record of fifteen wins to only one loss. At the height of their popularity and during the regular season, the confident team recorded the song and music video “The Super Bowl Shuffle” to raise money for charity. Chicagoans embraced the team’s exuberance and looked forward to a long-awaited Super Bowl match and victory. “The Super Bowl Shuffle” record cover. CHM, ICHi-075999

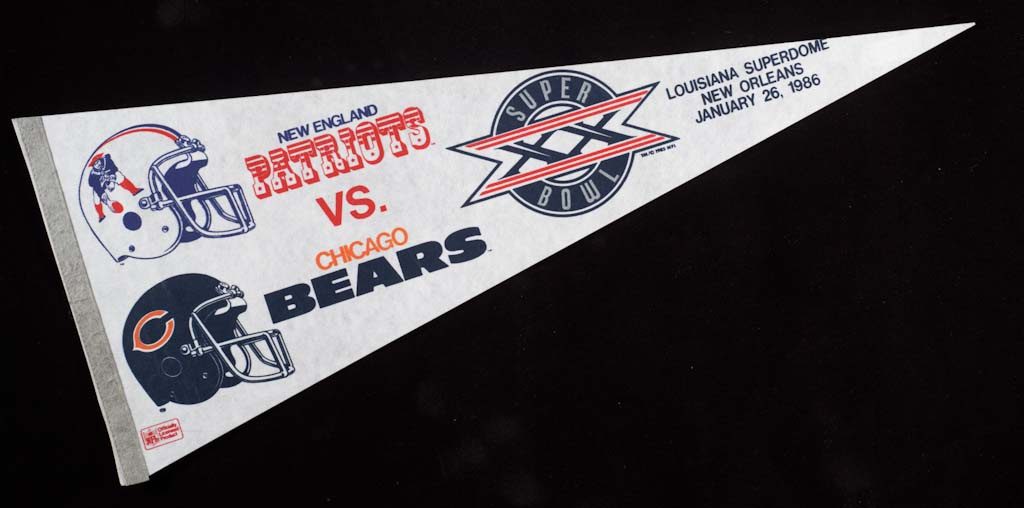

Their bravado was backed up when the Bears won a dominant 46–10 victory over the New England Patriots in Super Bowl XX. Super Bowl XX pennant. CHM, 1990.88.3.

The players and coach Mike Ditka were hailed as heroes at the Super Bowl victory parade on January 27, 1986. SDN-500043270073, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Chicago sports fans braved the frigid cold to celebrate a rare sports championship victory at a ticker tape parade in the Loop, January 27, 1986. CHM, ICHi-036236

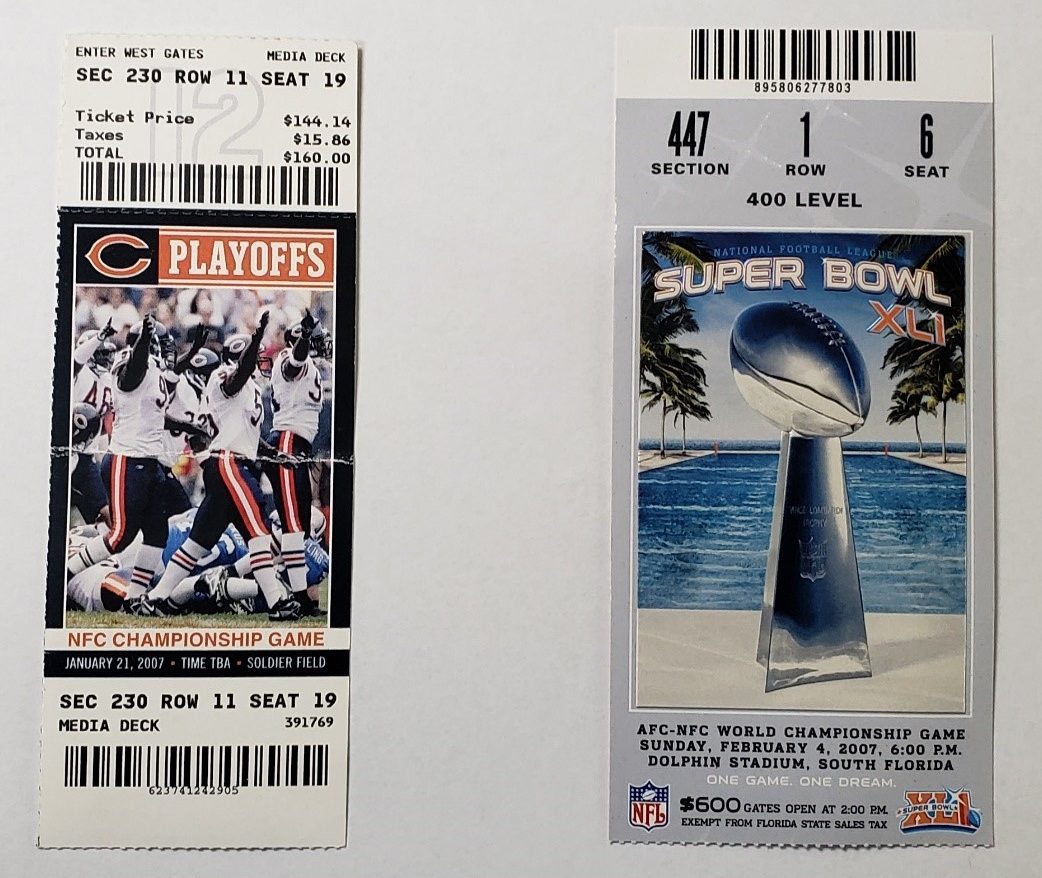

The Bears made it to the Super Bowl again in 2007. This time, however, they fell short, losing to the Indianapolis Colts 29–17. But as patient Chicago sports fans know, if they wait ’til next year, that elusive championship just might happen! Tickets to the NFC Championship Game (left) and to Super Bowl XLI (right). CHM, GV945 C21 M5Z Oversized

In this photo essay, take a look back at the events surrounding the infamous 1919 Black Sox scandal. The text is adapted from “Black Sox” by Robert I. Goler, which appeared in Chicago History, fall/winter 1988–89.

One hundred years ago, the Chicago White Sox lost the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. The infamous series has come to be known as the Black Sox scandal due to a group of eight White Sox players (dubbed the Black Sox by the press) allegedly agreeing to throw games in exchange for money from a group of high-stakes gamblers.

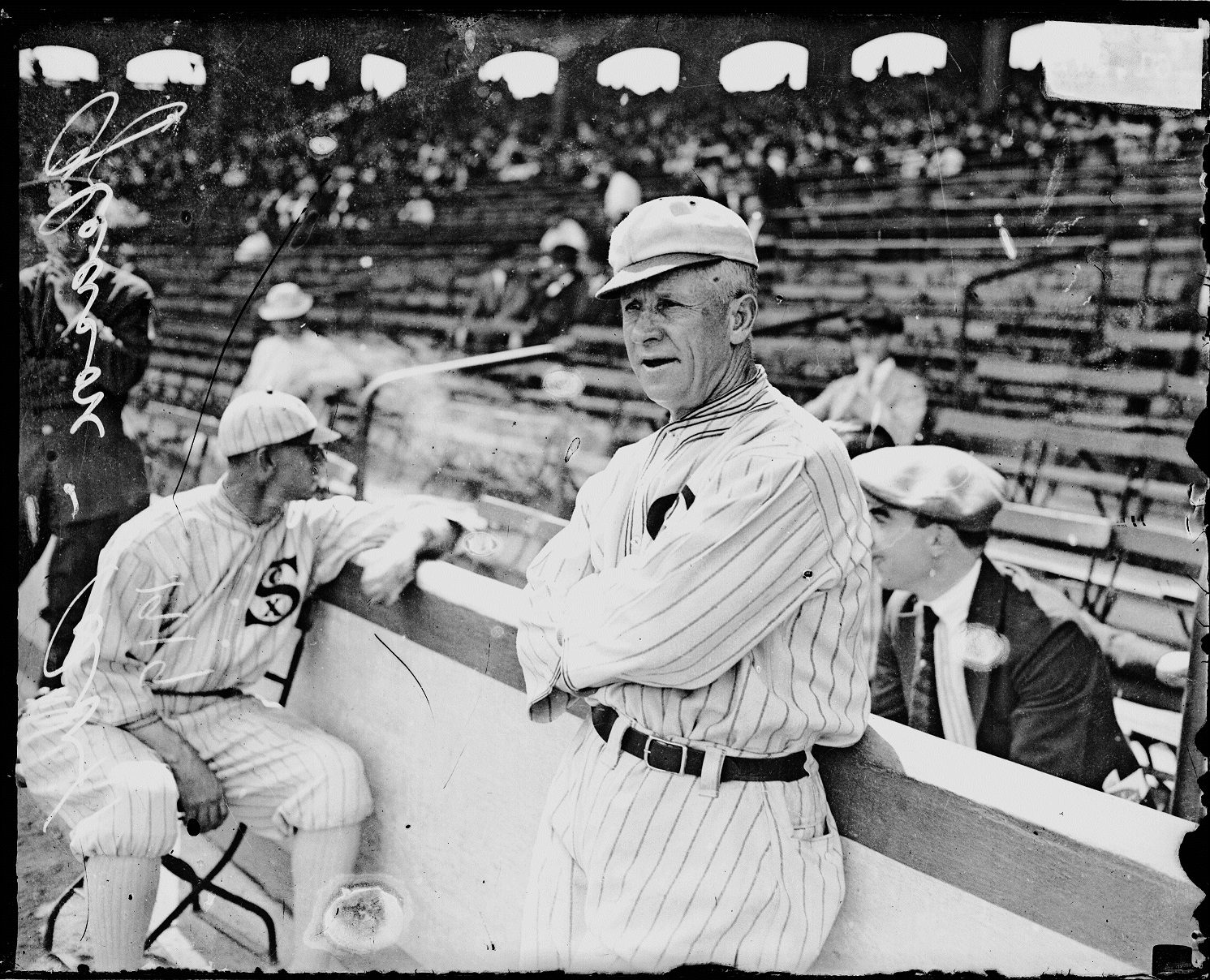

The White Sox had won the World Series in 1917. Their 1919 lineup was similar to that championship team, but they had new manager in William Kid Gleason.

Kid Gleason at Comiskey Park, 1919. SDN-061872, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

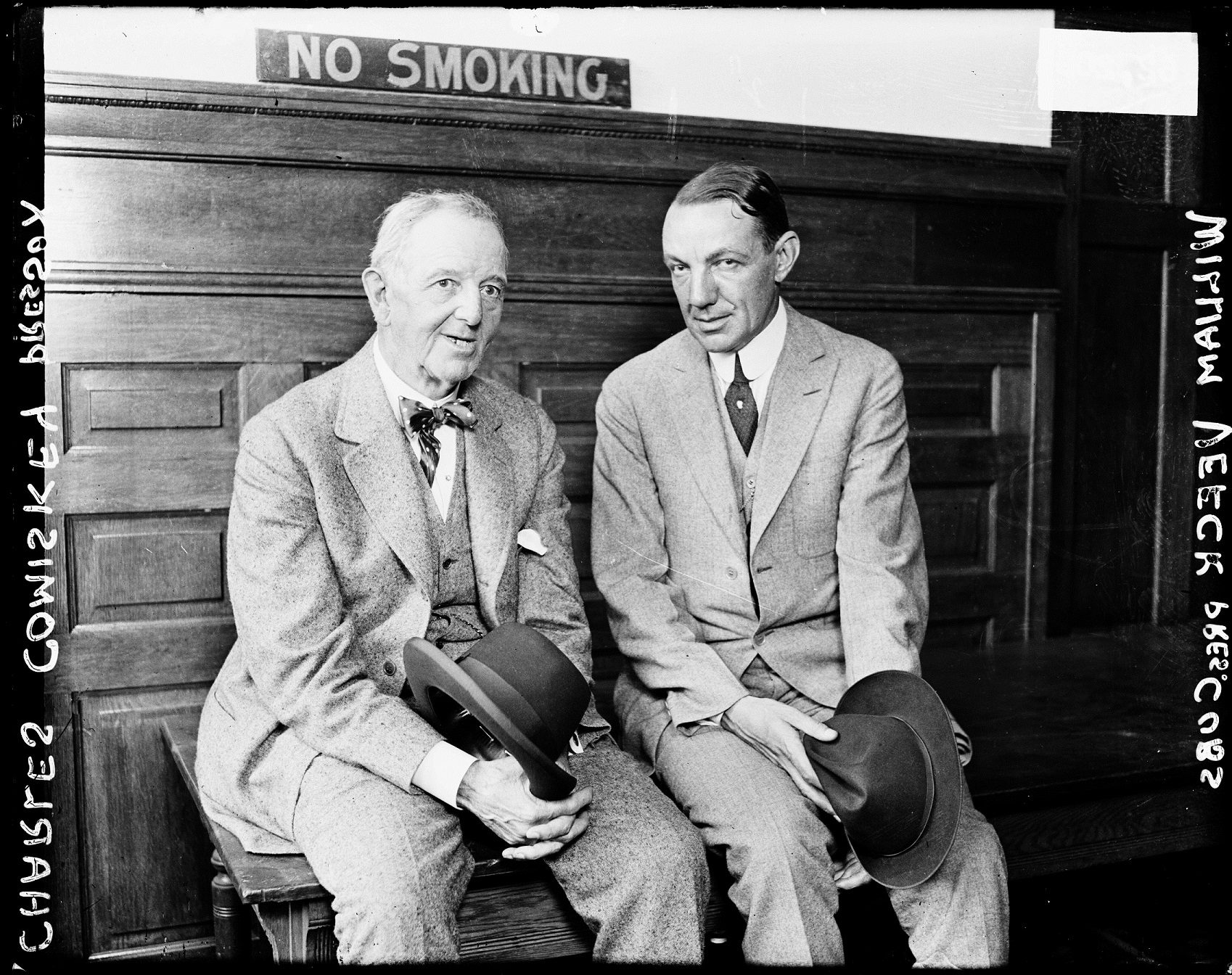

Among the myths surrounding the scandal is the notion that low salaries and team owner Charles Comiskey’s frugality angered some of the players. While it was true that without a union they had little bargaining power, White Sox players’ salaries were comparable to others in the league.

Comiskey, left, and Bill Veeck Sr., president of the Chicago Cubs, 1920. SDN-062205, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

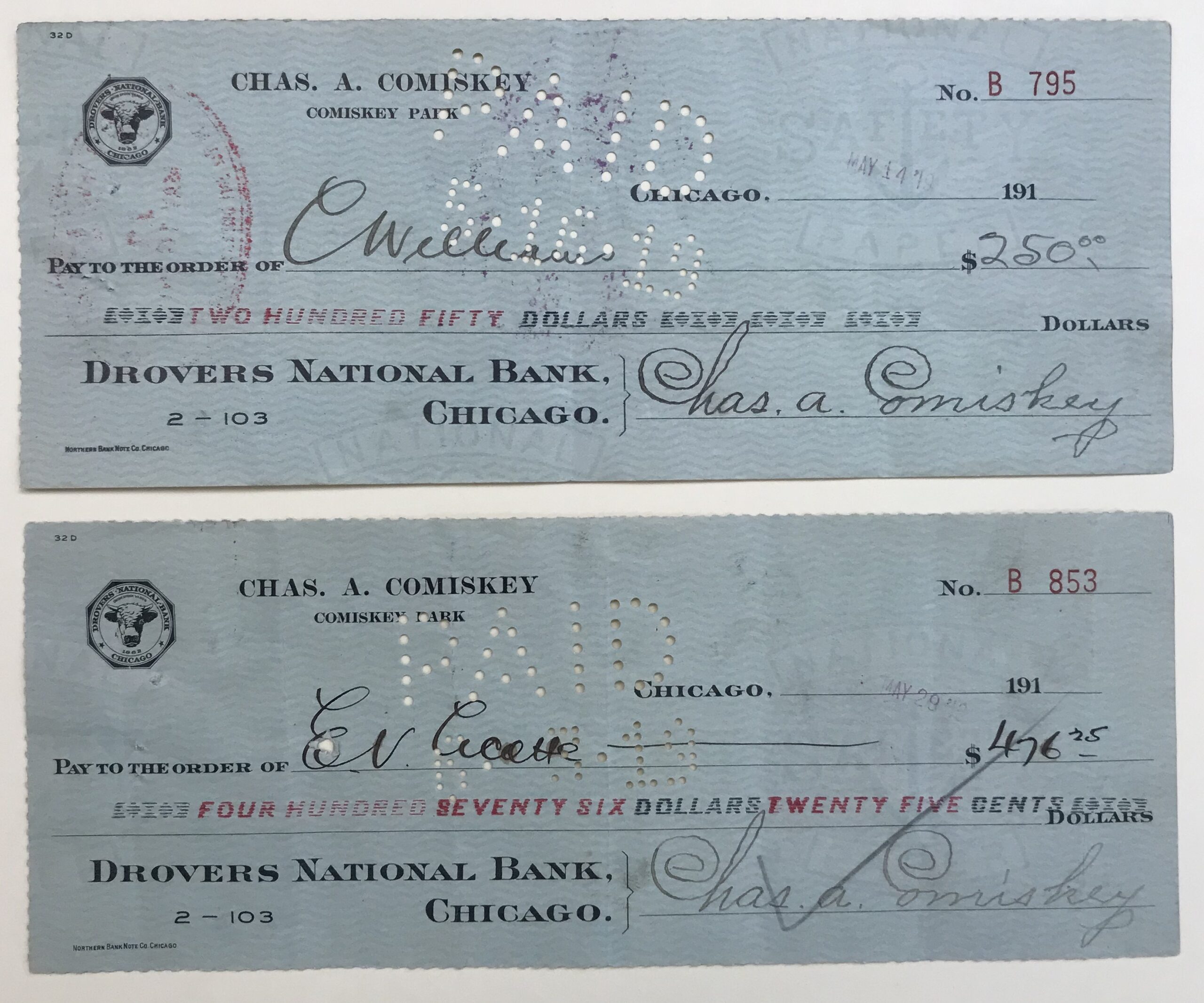

Paychecks (1919) signed by Comiskey and endorsed by players Cicotte and Williams, Chicago White Sox and 1919 World Series baseball scandal collection, 1917–1929, CHM

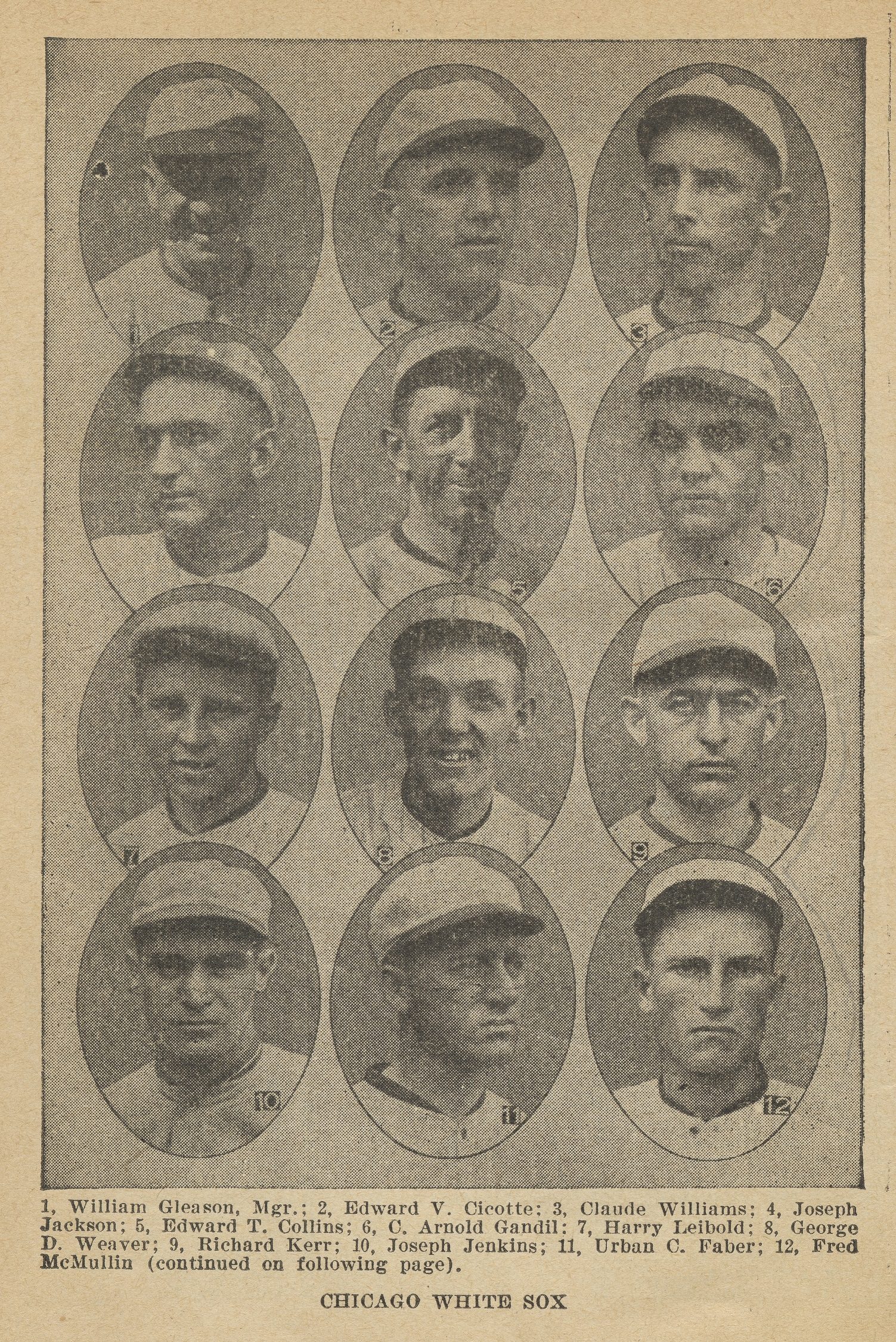

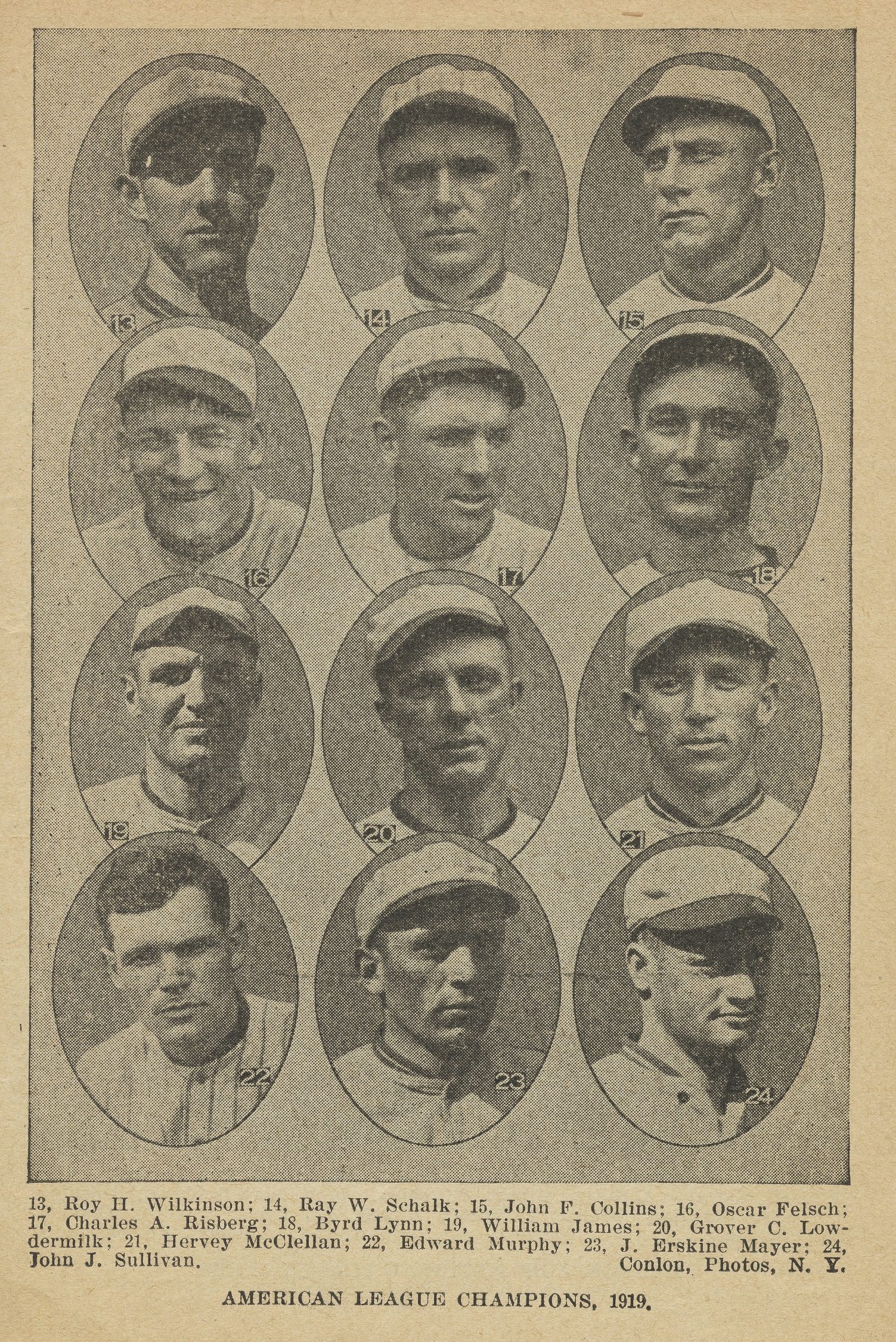

In 1919, the White Sox were the American League champions with a record of 88–52. Their lineup included the hitting power of star player Shoeless Joe Jackson, second baseman Eddie Collins, and pitching aces Eddie Cicotte, Claude Lefty Williams, and rookie Dickie Kerr.

The 1919 American League champion White Sox. CHM, ICHi-067451, ICHi-067452

The Sox were set to face the National League champion Cincinnati Reds, who had a record of 96–44 and the franchise’s first pennant. The 1919 World Series was a best of nine games and the first one since the end of World War I, so fans around the country followed it closely.

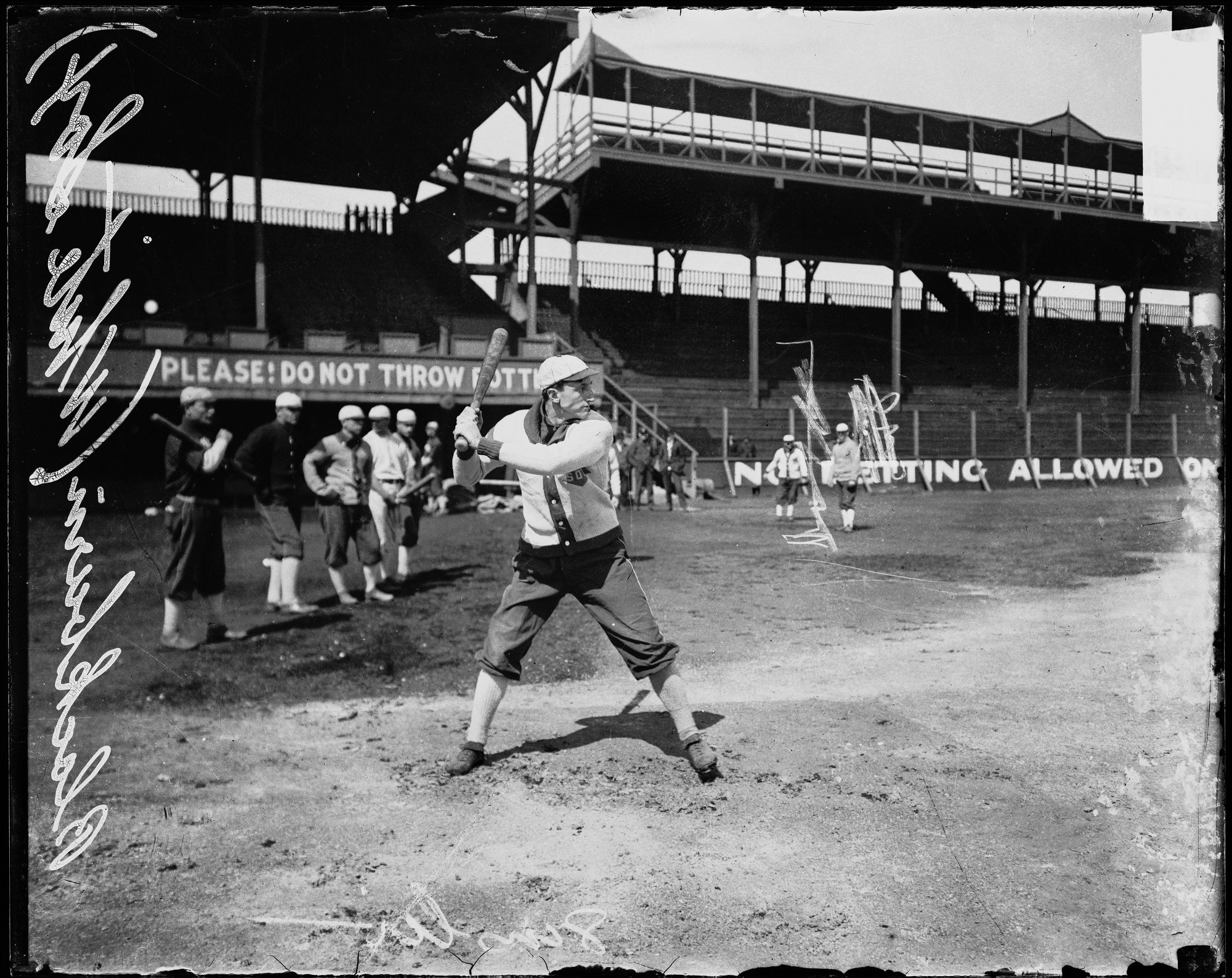

Baseball and gambling had been intertwined since the game’s beginning, and gamblers often attended games. In 1910, Comiskey even had a large sign painted down the left field line of South Side Park that proclaimed, “No betting allowed in this park.” Even so, fixing games was a long-suspected practice.

Lena Blackburne at home plate in South Side Park. Start of “No Betting Allowed” sign visible in back, June 11, 1910. SDN-056014, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

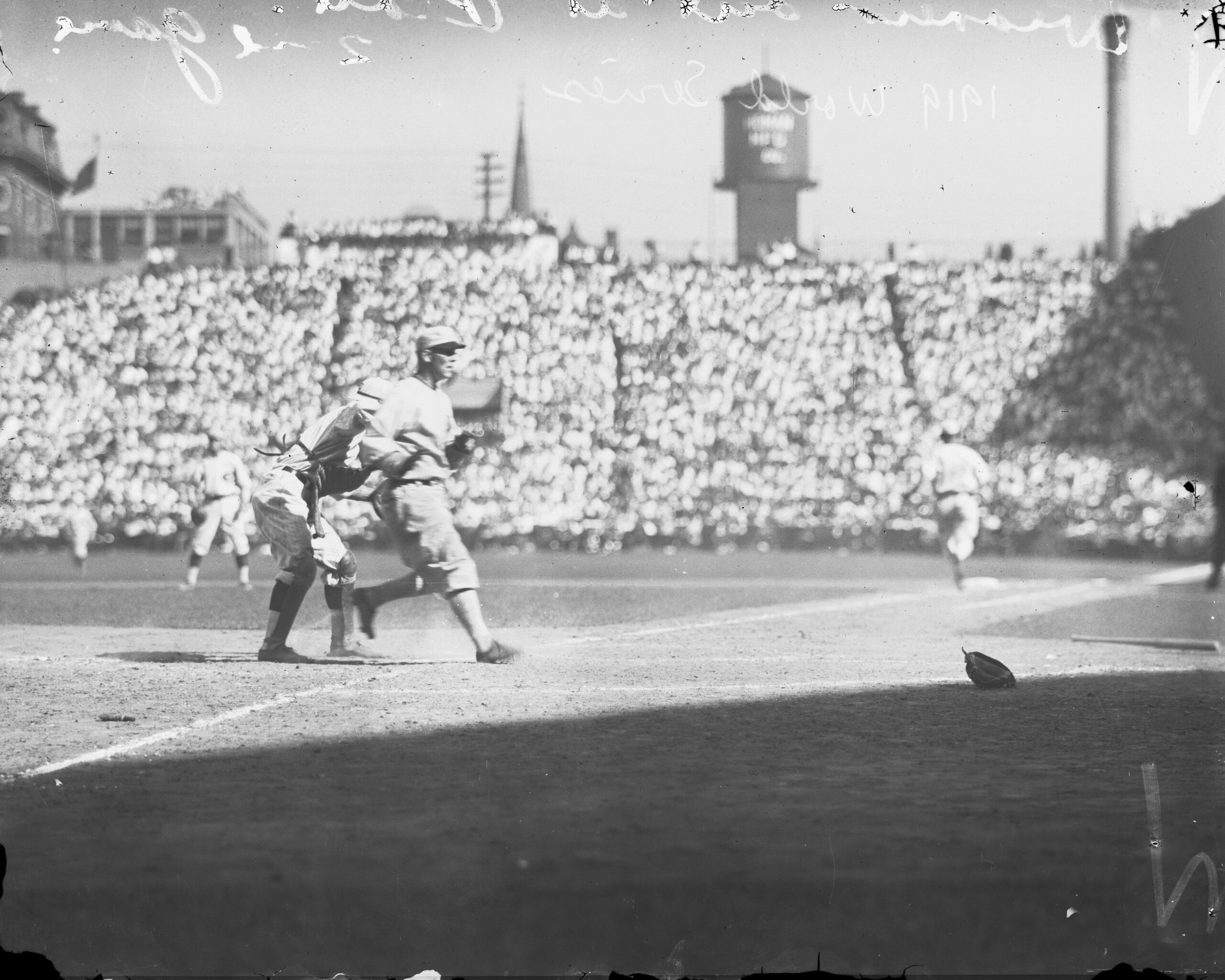

Chick Gandil being called out while attempting to steal second base during game 1, October 1, 1919. SDN-061952, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The more experienced White Sox were favored to win the series, but as game 1 approached, heavy betting changed the odds in Cincinnati’s favor. Indeed, the White Sox lost the first game 9–1, which the New York Times referred to as “a disastrous drubbing.” Gamblers continued to bet against Chicago, who also lost game 2.

Buck Weaver getting tagged out at home during game 2 at Redland Field, Cincinnati, October 2, 1919. SDN-061954, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The White Sox won game 3 at home, but Cincinnati would take the next two games at Comiskey Park. The White Sox seemed to rally, winning games 6 and 7 at Redland Field, but Cincinnati took the series in game 8 on October 9.

The scandal over the series publicly broke in September 1920, when the Philadelphia North American published an interview with a gambler named Billy Maharg, who described the fixing of the series. Similar accusations led to a Cook County grand jury investigation. On September 29, Eddie Cicotte, Lefty Williams, and Joe Jackson confessed to being involved in the fix. The allegations were that eight players were promised up to $20,000 to throw games and possibly the entire series. According to Cicotte’s deposition, he got the idea of fixing the series from talk among the players about “somebody” offering the 1918 Cubs team large sums of money to throw the series.

Comiskey suspended the seven players still in the majors: Cicotte, Jackson, Williams, Oscar Happy Felsch, Fred McMullin, Charles Swede Risberg, and George Buck Weaver (Charles Chick Gandil had not returned to the majors). On October 22, 1920, the grand jury indicted the eight players along with five gamblers on counts that included conspiracy to defraud.

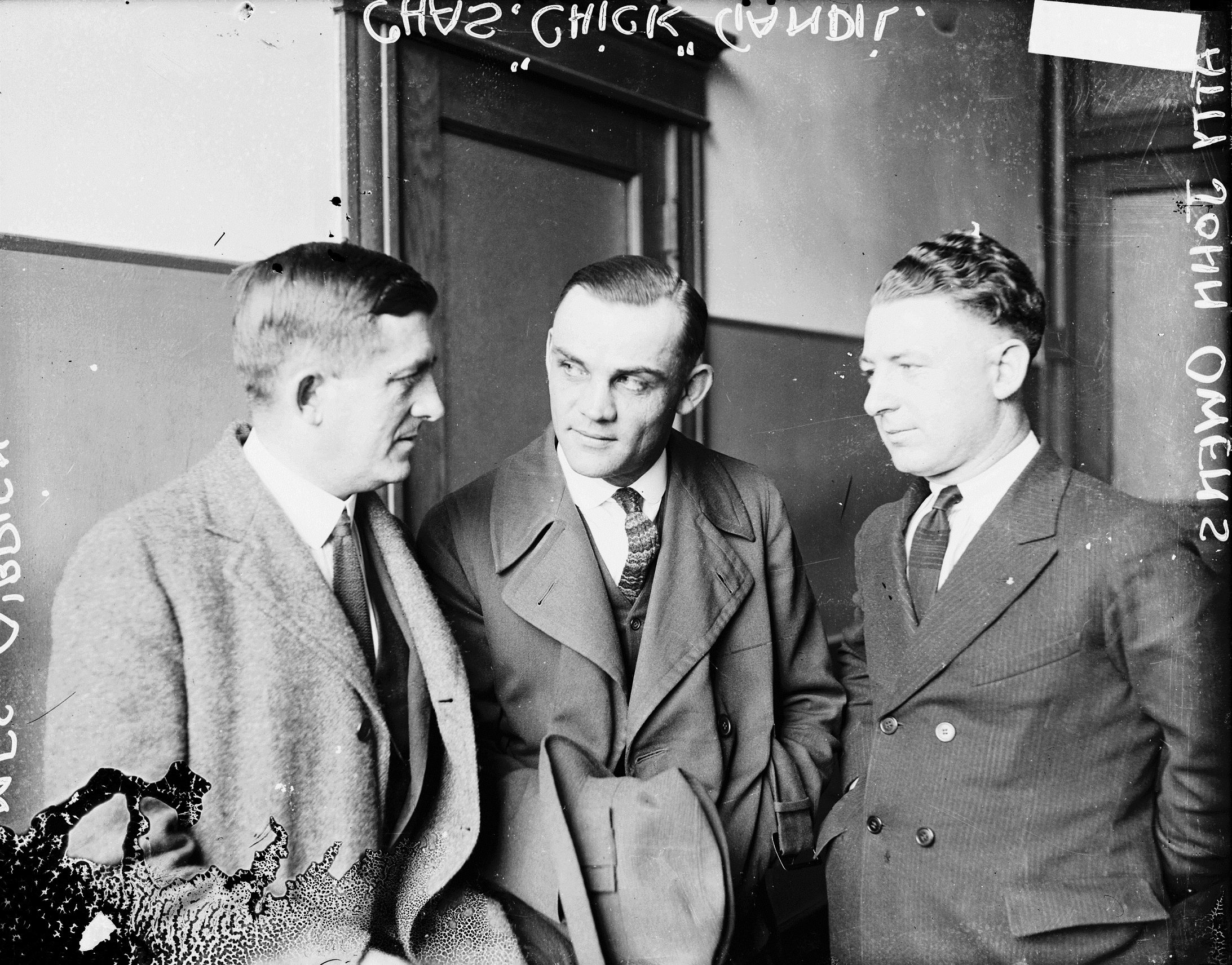

Gandil (center) standing with attorneys James C. O’Brien (left) and John Owens (right) during the trial, 1921. DN-0073157, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

White Sox player-defendants (seated, second from left) Jackson, Weaver, Cicotte, Risberg, Williams, and Gandil with their attorneys, 1921. SDN-062959, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The trial opened on July 18, 1921, and over fourteen days, the jury heard testimony from Comiskey, Gleason, and several of the gamblers, including Maharg. After deliberating for two hours and forty-seven minutes, the jury acquitted the players on all charges. No other charges were ever brought about for anyone else involved in the scandal.

The Black Sox scandal, however, did have a lasting impact on baseball. To improve the sport’s image, the league appointed its first commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, in 1920, who expelled all eight players from professional baseball. Investigations into the scandal continued, and several of the players sued over back pay. But most distanced themselves from the scandal and went on to work outside the sport.

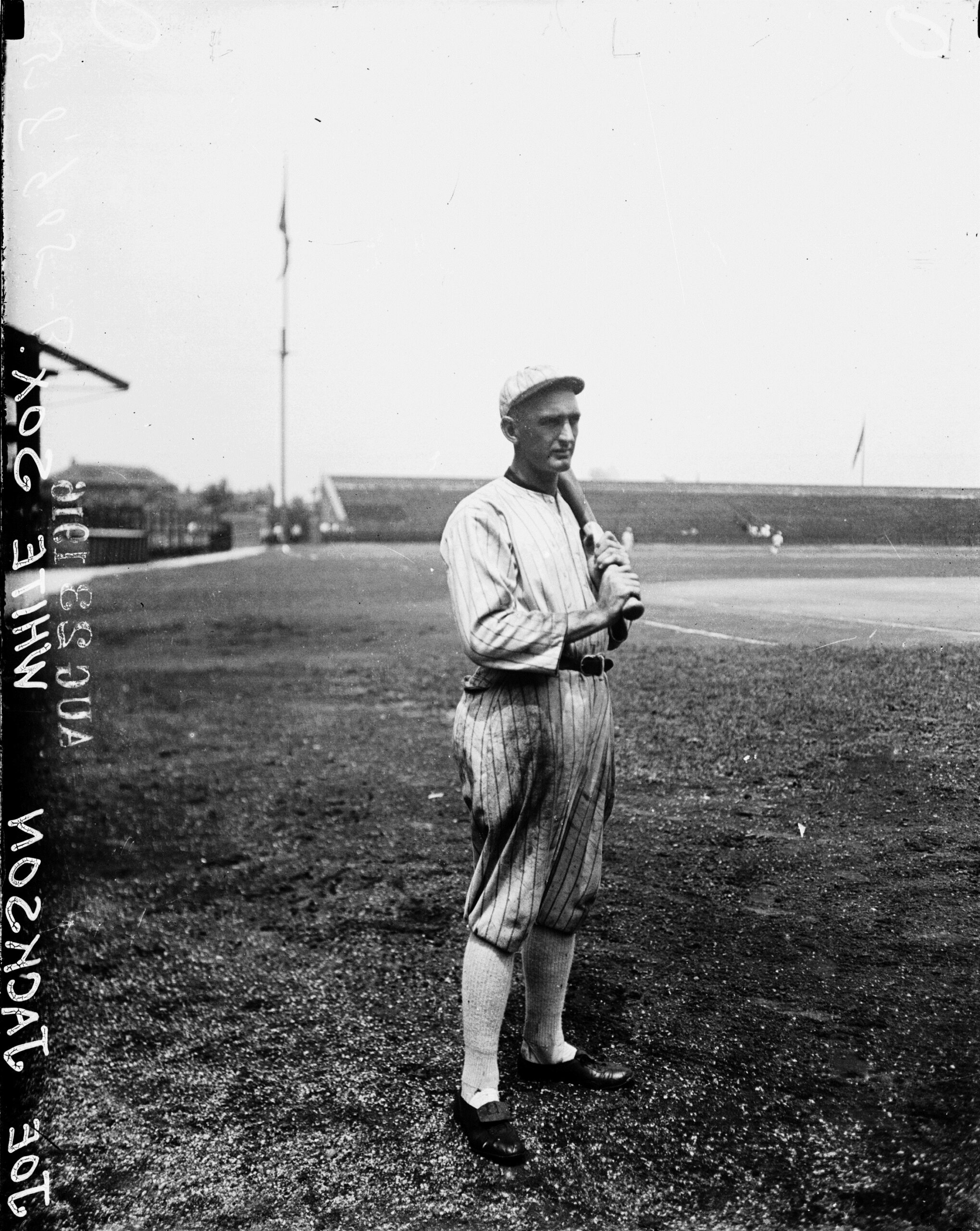

Shoeless Joe Jackson poses with a baseball bat in Comiskey Park, c. 1915. SDN-058905B, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

In the twenty-first century, the scandal remains controversial. One of the lingering questions is the involvement of would-be Hall-of-Famer Shoeless Joe Jackson, who to this day holds Major League Baseball’s third-highest career batting average. Attempts by Jackson’s fans to clear his name and allow him entry into the National Baseball Hall of Fame persist.

A version of this article, “Black Sox” by Robert I. Goler, appeared in Chicago History, fall/winter 1988–89. Read it on ISSUU.

Further reading

- The finding aid for the Chicago White Sox and 1919 World Series baseball scandal collection, 1917–29

- The finding aid for the Eliot Asinof papers

- The Black Sox: Baseball’s Enduring Enigma

- 2019 SABR Black Sox Scandal Centennial Symposium

CHM collections intern Araceli Medina recaps her work this past summer assisting with the ongoing inventory of the Decorative and Industrial Arts collection. Through the inventory process, Medina saw first-hand how objects can tell stories that help us understand the past as it was lived.

The process of inventorying a museum collection is important and requires a lot of time, but it is always full of surprises. This summer, I worked as an intern for the Decorative and Industrial Arts collection, and I got to learn more about several centuries worth of objects from the Charles F. Gunther Collection.

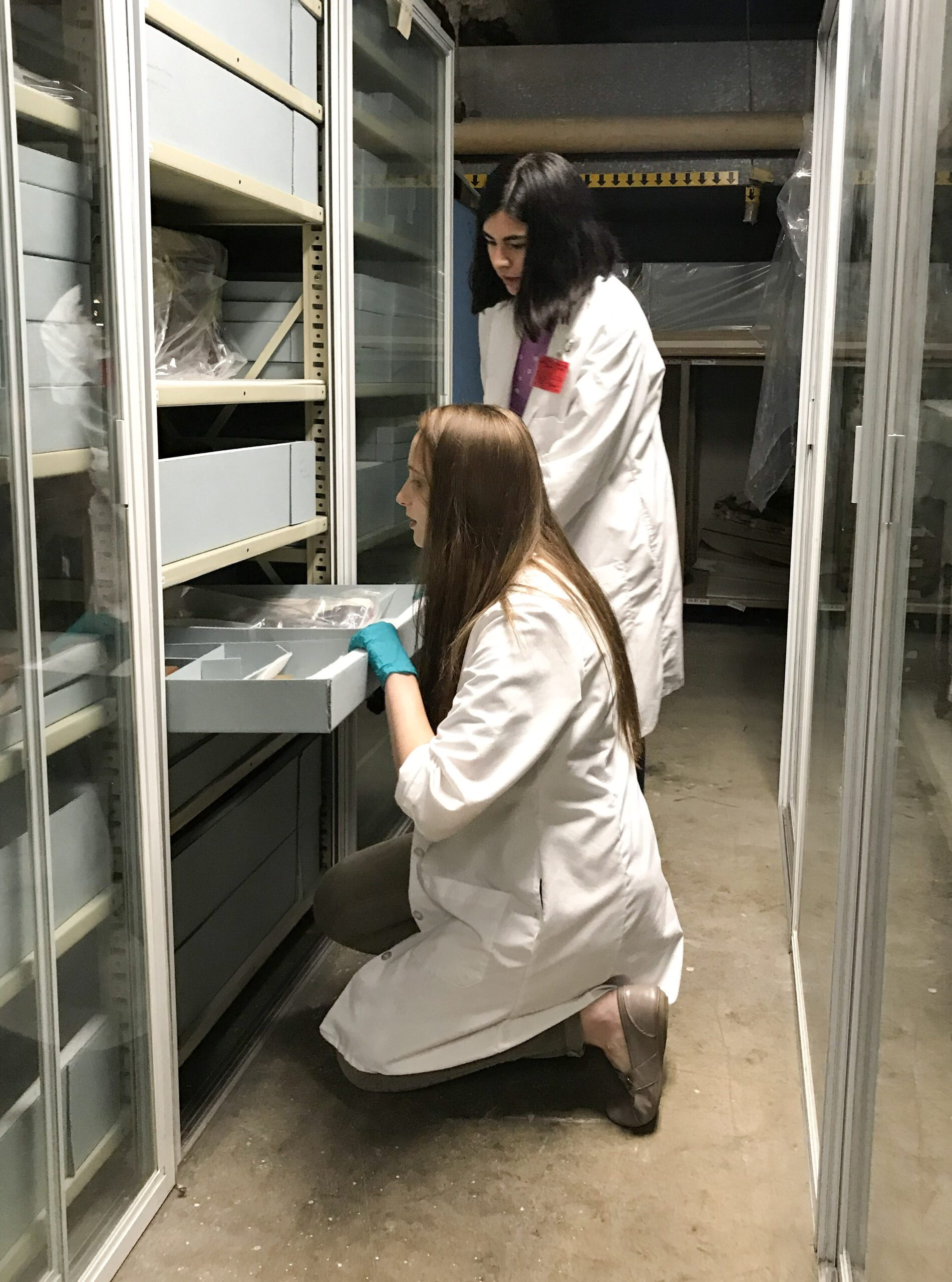

Medina (left) and fellow intern Elise O’Neil transport a cart of artifacts. All photographs by Chicago History Museum staff

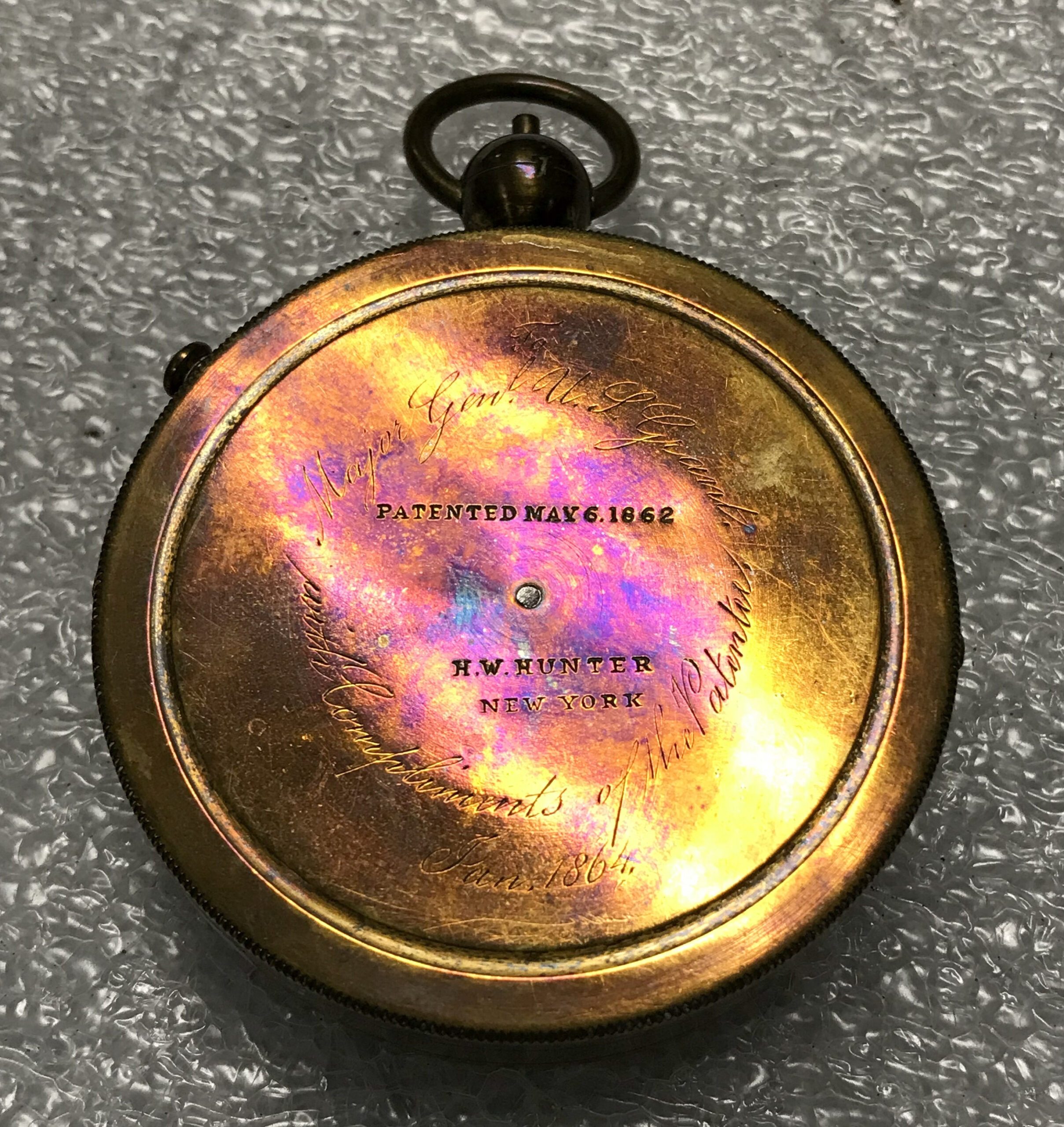

Objects have value imbued upon them in varying ways and this was quite evident through the inventory process. I got to see what objects people valued enough to save for future generations and to consider how certain values shift over time. People go through many lengths to safeguard relics to commemorate famous individuals. One example is Ulysses S. Grant’s compass, which he obtained during the Civil War. He most likely valued it because it was useful in his daily life. However, other objects seemingly were not of value to the famed individual, but their mere association warrants attention from future collectors.

Inside and back of Grant’s compass. Inscription reads: “Major General U.S. Grant with Compliments of the Patentee.” CHM, 1935.164a-b

Another example is a fruit knife that once belonged to Mary D. Green. She was given this knife as a gift by Tad Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln’s son, since she was his school teacher. She herself is not a known figure but because of her association with Lincoln, this object’s context and value changes.

Mary D. Green’s knife. Inscription reads “M.D.G.” CHM, 1919.36

History becomes alive as one goes through the cabinets that store the collection. This is why museums are of great importance. They safeguard and collect objects so that people can later see what, for example, a telegraph cable from the early twentieth century looked like, or one can imagine the life of a soldier during the Civil War by looking at a small wallet they carried or a powder horn they decorated on their downtime. With multiple centuries worth of objects within the Museum’s collection, one gets a sense of how our understanding of the world and the things we value change over time.

One of the earliest objects we found is a globe made in 1603 by Gulielmas Nicolai. The globe functions as a way to look at the world through the lens of a European individual from the seventeenth century. For example, Cuba is much larger on the globe than we know it to be today, as is Florida, which is shown as making up most of the US. Additionally, the Pacific Ocean is so narrow it appears more like a river than an ocean. This demonstrates the unfamiliarity of the Western Hemisphere at this time and how it was slowly being pieced together.

Seventeenth century globe. CHM, 1938.38a-b

Another snapshot of history we found as we inventoried the collection was a bracelet made of bone during the Civil War by a Union soldier. The words “Libby Prison” are inscribed on it. This is just one of many artistic pieces we found made at the Confederate Libby Prison, and when contextualized it keeps a record of what life was like in the prison.

The center heart piece of this bracelet is inscribed with “Bell Island VA. Aug 11 1868.” CHM

The value we place on objects differs for many reasons, and through the inventory process I observed distinct valorizations through different historical lenses. Ultimately, I learned while investigating the objects in this collection that keeping these value differences in mind helps to make sense of the context of their time as well as the present.

- Read more on managing collections storage.

- Read more posts on collections inventory.

This past summer, CHM collections intern Elise O’Neil assisted with the ongoing inventory of the Decorative and Industrial Arts collection. In this blog post, O’Neil writes about the legacies that objects reflect, depending on who owned them.

As a lifelong history nerd, working at the Chicago History Museum as a collections intern this summer and doing inventory for the Charles F. Gunther Collection far exceeded my expectations. One thing I observed firsthand in the inventory process is how the historical value given to an object is tied to the legacy of its owner.

O’Neil (foreground) and fellow intern Araceli Medina return an item to storage. All photographs by Chicago History Museum staff

One of the first objects we inventoried that caught my eye was an ivory-handled meat carving set. A quick computer search yielded no information about it, so I put it aside. But upon further research, I found out that the carving set had belonged to George Washington. Immediately its importance rose in my estimation. This man whose legacy is intertwined with the genesis of the United States perhaps held these objects in his hands. The quick turnaround from mild disinterest in this carving set to glowing admiration at the suggestion of association with a famous historical figure was a lesson for me in how we understand historical value. This carving set didn’t pertain to Washington’s legacy at all, but it is considered special because he used it.

Carving set with bust of Washington on the handles. CHM, 1935.40abc

I began to see this pattern in my response to objects and the value I gave them as the summer went on. A rectangular whetstone became important because it had belonged to Abraham Lincoln.

Whetstone used by Lincoln. CHM, 1931.50

A pen drew my interest because it had been used by Ulysses S. Grant to write his memoirs. But these are everyday utilitarian objects. Surely Lincoln didn’t imagine the stone he used to sharpen his knives would be passed down as a relic through generations. And it’s doubtful that Grant, as he raced to finish his memoirs before his death, was giving much thought to the legacy of the pen he was using.

Written on the pen: “Used by Gen. Grant. From Estate of Frank H. Jones.” CHM, 1935.165

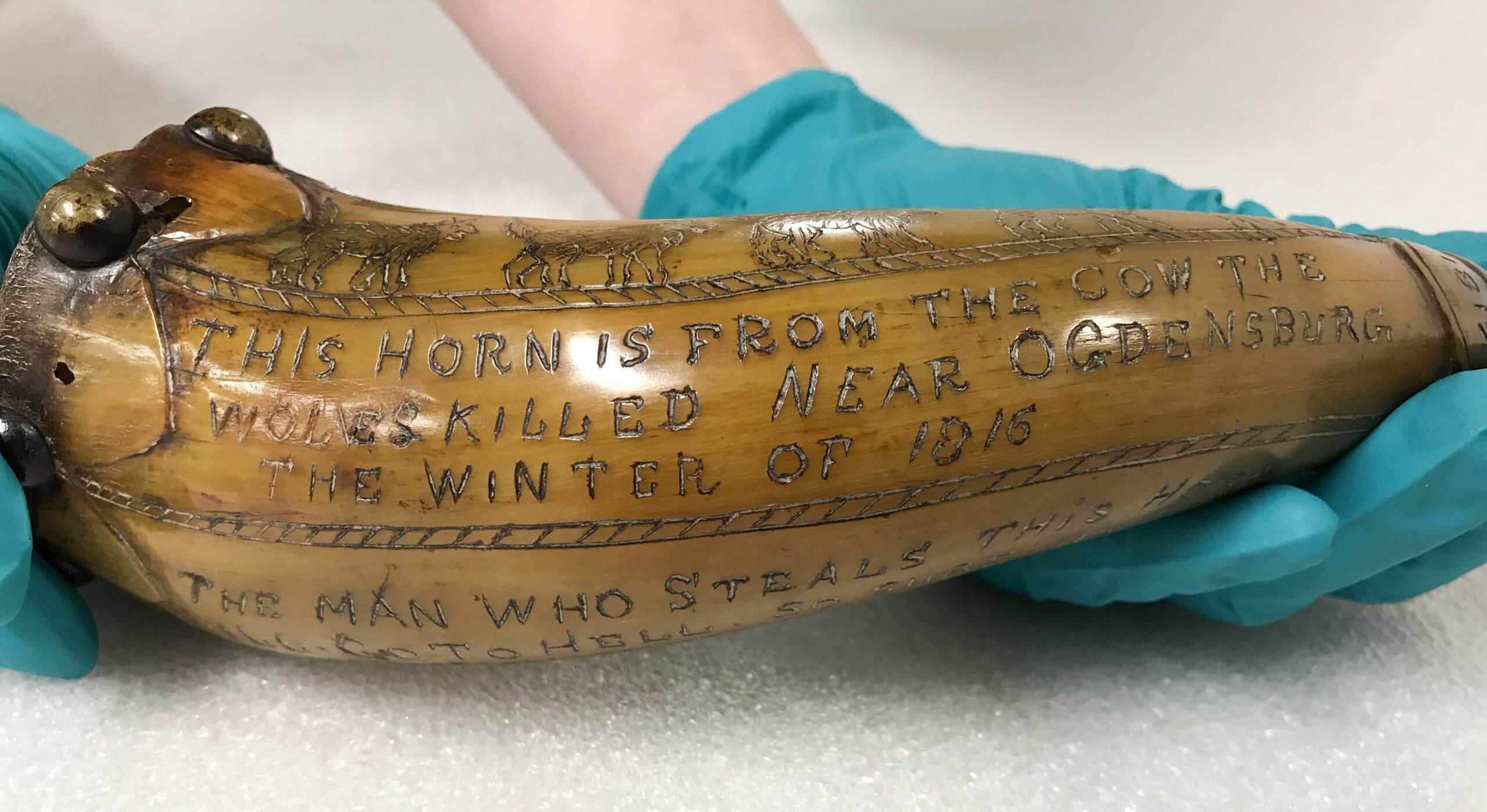

But then I stumbled upon an everyday object that was a legacy itself. A powder horn, used by its owner to hold gun powder, was carved with a record of the owner’s exploits. After describing the origin of the horn and delivering a threat to anyone who dared to steal it, James Fenwick of Ogdensburg listed the precise number of bears, wolves, deer, and partridges he had killed in 1817. Here on this object was an account of the pursuits that were meaningful enough to this man to keep a record of them. When I searched for Fenwick online, I was unable to find anything about him not related to the powder horn. He had no lasting legacy like that of Washington, Lincoln, or Grant, but this horn was proof that he had lived and triumphed in some small way.

Carved on the powder horn: “This horn is from the cow the wolves killed near Ogdensburg the winter of 1815 / The man who steals this horn will go to hell. So sure as he’s born.” CHM, 1920.503

Continuation of the carving: “I, James Fenwick of Ogdensburg / Did the year of 1817 kill 30 wolf; 10 bear; 15 deer and 46 patridge [sic]” CHM, 1920.503

In Hamilton: An American Musical, Lin-Manuel Miranda proposed that a legacy is “planting seeds in a garden you never get to see.” For men like Washington and Lincoln, this seems to be true. Their actions produced many far-reaching consequences remembered by history. This is why we place value on the objects they owned. But other collection objects show that a legacy can also be held in one’s hands, like a powder horn carefully carved when the day’s work is done.

Additional Resources

- Read more on managing collections storage.

- Read more posts on collections inventory.

In this blog post, CHM curatorial intern Brigid Kennedy recounts the life of labor organizer Lucy Parsons.

The details of Lucy Parsons’s early life in Texas are murky, and she herself provided different accounts of her youth and heritage. Her race was the subject of public debate, but she claimed only Mexican and Muscogee Creek ancestry. These ethnicities, and the popular suspicion that she was at least in part Black, were used in attempts to discredit her politics and activism.

Lucy Parsons in Chicago, 1915. ICHi-027212, Chicago Daily News Negatives Collection, CHM

Parsons was likely born in 1853 and moved to Chicago at age twenty with her new husband, Albert, in the middle of a nationwide economic depression. Chicago was hit hard, still reeling from the Great Fire, and resources were strained. Out of these brutal conditions emerged a labor rights movement, and Lucy and Albert, a Confederate soldier turned radical Republican, quickly established themselves as key figures within it—even opening their home to meetings of the Workingmen’s Party.

When Albert was blacklisted after his involvement in the nationwide strikes of 1877, Lucy opened a dress shop to provide for the family. She then helped organize the Working Women’s Union (WWU), which allowed women who worked as domestic servants, seamstresses, homemakers, and in similar professions to organize. The WWU advocated for women’s labor needs, such as equal pay for equal work and women’s suffrage, though Parsons herself was disillusioned with electoral politics and not active in the suffrage movement. Eventually she stopped working with unions because they focused on reform rather than radical reorganization of society—though she continued to support the working class.

This bomb casing was presented as evidence in December 1887 during the trial of Louis Lingg, one of the eight men accused of homicide after the Haymarket bombing. CHM, ICHi-31957a

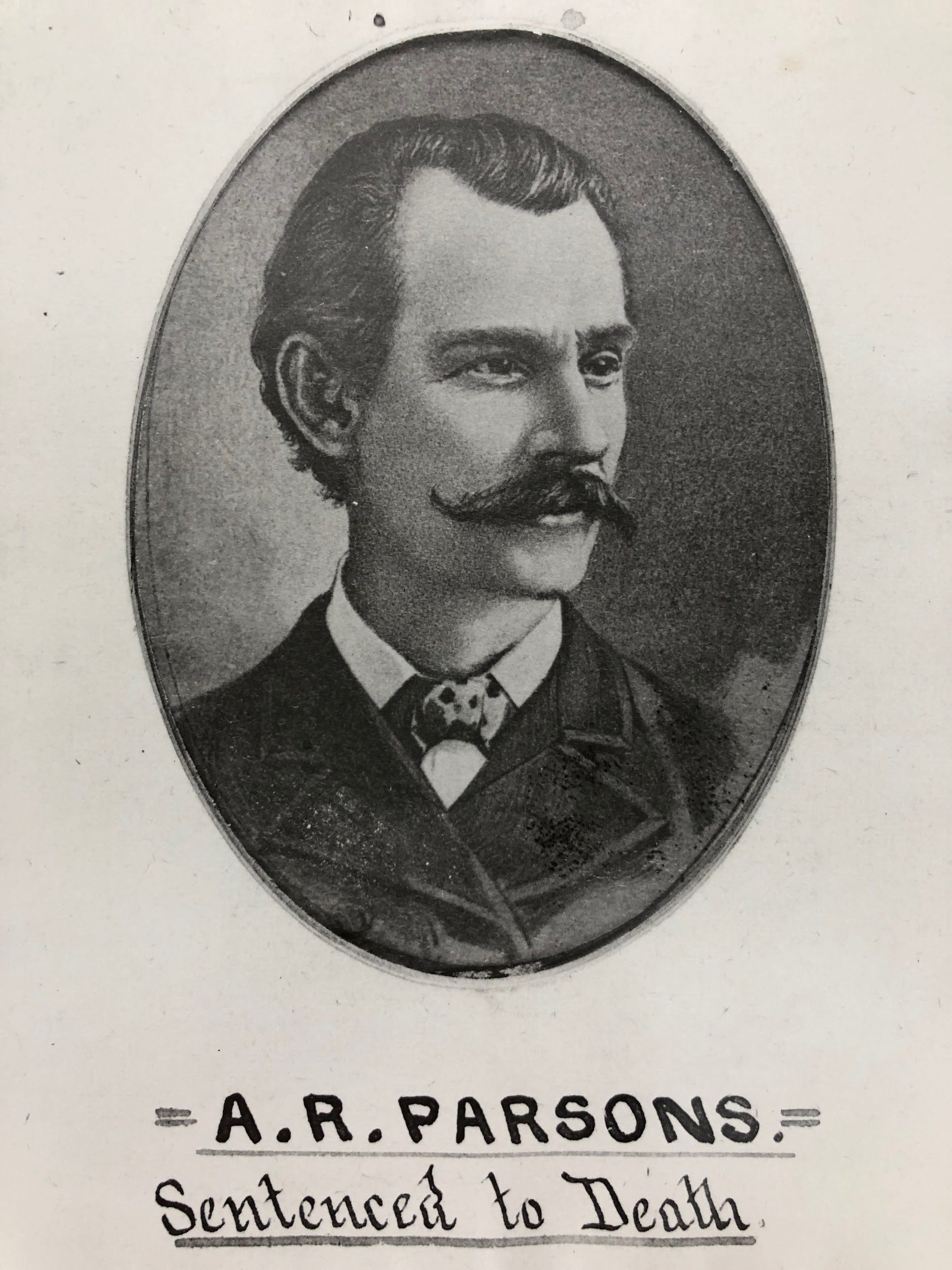

On May 4, 1886, Chicago police broke up a gathering in Haymarket Square, which had been called to discuss police brutality in response to labor organizing. Someone in the crowd threw a bomb, which led police to shoot aimlessly into the crowd. Albert Parsons and four other anarchist leaders were ordered to be hanged for having incited the crowds with their speeches, despite a lack of evidence for their involvement in the violence itself.

An undated portrait of Albert Parsons with news of his Haymarket sentence. A.R. Parsons, Image file – People P, CHM

After Albert’s death, Parsons devoted herself to publishing on and supporting Chicago’s anarchist movement. She served as editor of the Liberator, an anarchist newspaper, and cofounded a periodical with Lizzie Swank Holmes called Freedom: A Revolutionary Communist-Anarchist Monthly. Here, she found an outlet and an audience for histories of communism, biographies of the Haymarket martyrs, antilynching pieces, and analyses of the oppression of women and of US racism.

Parsons also continued the activism she’d begun before Haymarket. In 1905, she cofounded the Industrial Workers of the World in Chicago with leaders like Mother Jones, Bill Haywood, and Eugene Victor Debs. She continued her activist work, but not without incident. Parsons was arrested after speaking at a meeting of the unemployed on January 17, 1915, and had her bail paid by Hull-House’s Jane Addams. Then, during World War I, and as American fear of communism increased, the US Postal Service refused to send radical publications.

An undated photograph of Parsons pointing to a portrait of Albert in her home in Chicago. Lucy Parsons, Image file – People P, CHM

Despite these obstacles, Parsons continued to work until her death on March 7, 1942, in a house fire. She spent her life challenging oppressive power structures and remains a controversial figure, but one whose actions laid the groundwork for the Chicago we know today.