Latest Posts

The Chicago History Museum’s newest exhibition Treasured Ten: Selections from the Costume Collection will be open to the public starting Saturday, April 9, 2022, and run through Monday, January 16, 2023. The exhibition features an eclectic arrangement of garments from the Chicago History Museum’s clothing collection of more than 50,000 pieces. These ten never-been-exhibited ensembles were selected to tell the remarkable stories of five designers Stephen Burrows, Scotty Piper, Patrick Kelly, Willi Smith, and Barbara Bates.

“I am excited for people to view these ten never before displayed garments created by five innovative designers who each have a fascinating story to tell,” said Jessica Pushor, collections manager of costume and textiles at the Chicago History Museum.

Dating from the 1970s to the 1980s, these garments are expressions of their creators’ experiences and identities. In their experiences dressing celebrity clientele as well as everyday people, each designer produced engaging, conscientious, and stylish designs while contributing their own perspectives to fashion.

“Having spent many years inventorying and cataloging the collection, I am always amazed by the objects I come across.” said Pushor. “This exhibit is a new opportunity to publicly showcase previously unseen treasures from our massive costume collection, and to be more inclusive in the Chicago stories we tell.“

Exhibition Overview

Treasured Ten: Selections from the Costume Collection will be presented in a single gallery with 10 dressed mannequins wearing two ensembles by each designer. The gallery will also feature a playlist of songs that inspired each designer and several thematic arrangements of images and colorful panels unfolding around the walls and interior of the gallery.

Museum members can enjoy early access to the exhibition on Friday, April 8, during a preview night with co-curators Jessica Pushor and Charles E. Bethea, and special guest Barbara Bates. The Chicago History Museum is partnering with University of Illinois at Chicago and The Crafty Corner for a teen program “Chicago Threads.” This will be an 8-week summer design program, which will culminate in a fashion show in late summer 2022.

This exhibition is sponsored by The Costume Council of the Chicago History Museum.

For more information on Treasured Ten: Selections from the Costume Collection please visit: www.chicagohistory.org/treasuredten.

Portrait of Ella G. Berry. Published on in The Story of the Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs 1900–1922 by Elizabeth Lindsey Davis, 1922. CHM, ICHi-177302A

Ella Berry was born Ella Tucker in 1876 in Stanford, Kentucky. Little is known about her father, Dave Tucker, but in 1870, her mother, Matilda Portman, was working as a live-in domestic for a white family. By the 1880s, Matilda had enough to purchase a small piece of property and temporarily stopped working in white households. She had six children—Ella, her sister Maggie, and four sons, who contributed to the family income as laborers. By 1884, Matilda began to relocate the family to Louisville, which is where Ella attended school.

Ella completed high school in Louisville and became involved in Black social organizations in the city. Around 1896, she married William Berry, but by 1900, Ella sought a divorce. When she migrated north after her mother’s death in 1902—first to Cincinnati, then to Chicago in 1907—she presented herself as married or widowed, likely to avoid the stigma of divorce. Ella held several government jobs in Chicago—including as an investigator for the Chicago Commission on Race Relations after the 1919 race riot and a home visitor in the Department of Public Welfare.

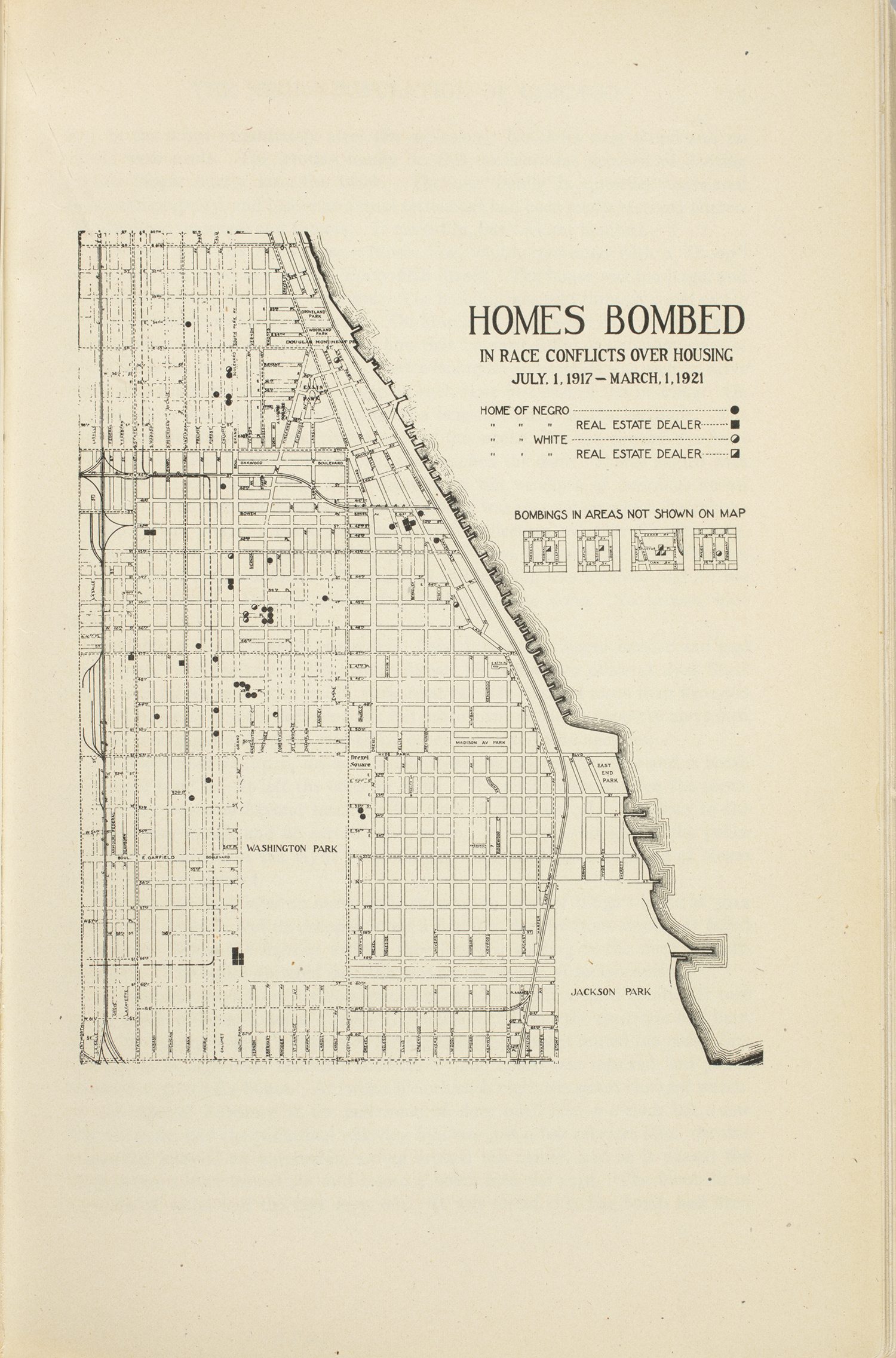

Map of homes bombed in racial conflicts over housing, July 1, 1917–March 1, 1921, published by the Chicago Commission on Race Relations. CHM, ICHi-177153

Ella was active in electoral politics. While living in Kentucky, Ella witnessed southern Democrats’ creation of Jim Crow laws and efforts to prevent Black people from voting. This shaped her view of the importance of African Americans’ collective voting power and her support for Republican candidates in the 1910s and ‘20s, as the Republican Party in the past had used federal power to protect civil rights for African Americans in the South.

After Illinois women were granted partial suffrage in 1913 to vote for local offices and in presidential elections, Ella canvased for Republican candidates. In 1914, she joined Chicago’s Second Ward Political Equality League to rally support for a Black independent Republican city council candidate. In the 1916 presidential election, Ella organized Black women to support Republican Charles E. Hughes, who was challenging incumbent Woodrow Wilson, whose administration increased discriminatory and segregated hiring practices in the federal government.

Ella was also active in local women’s clubs and national fraternal organizations. She joined the Cornell Charity Club in 1913 and had a parliamentarian role in the Illinois Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. She was also active in the United Brothers of Friendship and Sisters of the Mysterious Ten, the Order of the Eastern Star, and the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of the Elks of the World.

Chicago mayor Edward J. Kelly, Chicago, 1928. DN-0085926, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

By the mid-1930s, Ella was part of the voting realignment of African Americans to the Democratic party, and she canvassed for Democratic mayor Edward Kelly’s reelection bid in 1935. When she died in Chicago in 1939, she was eulogized by multiple community leaders, which showed her impact in civic and political life in Chicago.

Further Reading

- Online experience: Democracy Limited: Chicago Women and the Vote

- Lisa G. Materson, For the Freedom of Her Race: Black Women and Electoral Politics in Illinois, 1877–1932 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

- Wanda Hendricks, Gender, Race, and Politics in the Midwest: Black Club Women in Illinois (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998).

On January 26–27, 1967, Chicago experienced its worst snowstorm on record. The snow began at 5:02 a.m. on Thursday, January 26, and by 10:10 a.m. the next day, a record 23.0 inches of snowfall from a storm blanketed the city. High winds caused considerable blowing, with drifts of 4 to 6 feet widespread throughout the area.

Aerial view of cars stuck on Greenview Avenue in Rogers Park, Chicago, January 26, 1967; ST-17500889, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Just two days before the storm, the high temperature was a record 65°F, and the low was 44°F. But on January 25, a cold front moved through the upper Midwest, replacing the balmy temperatures. Dew points in the 50s–60s over the Southern Plains and Gulf Coast states provided ample moisture, while high pressure centered over Lake Superior and southern Ontario kept cold dry air moving over the Great Lakes. That high pressure along with low pressure over the Ohio Valley caused winds to howl off Lake Michigan.

Cars covered with snow on Rosemont Ave. looking east from California Ave., January 1967; CHM, ICHi-035577, Howard B. Anderson, photographer

By noon, about 8 inches of snow was already on the ground, and O’Hare airport was shut down. Some schools and businesses released students and employees early, but the commute home was still treacherous. By Friday morning, Chicago was at a standstill—20,000 cars and 1,100 CTA buses were stranded. Helicopters delivered medical supplies to hospitals as well as food and blankets to stranded motorists. At least a dozen babies were born at home, though some expectant mothers were taken to hospitals by sled, bulldozer, and snowplow.

One man pushes a snowblower while two men pull with a rope to clean the sidewalk after the blizzard, January 1967; CHM, MDN-0000013

By January 28, Chicago had begun to dig itself out. Although CTA buses were operating most lines, abandoned vehicles hampered cleanup, and snow had to be hauled by dump truck to the Chicago River. Railcars of snow were even delivered to Fort Myers Beach, Florida, after 13-year-old Terri Hodson wrote a letter to the president of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad, having never seen snow before.

Packing snow in a refrigerated rail car to send to Florida, February 20, 1967; ST-15002021-0012, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

O’Hare finally reopened around midnight on Monday, January 30, but most schools didn’t reopen until Tuesday. In the end, 60 people in the Chicago area died, and there was an estimated $150 million in business losses (equivalent to $1.19 billion today). The snowstorm was likely the biggest disruption to the commerce and transportation of Chicago of any event since the 1871 Great Chicago Fire.

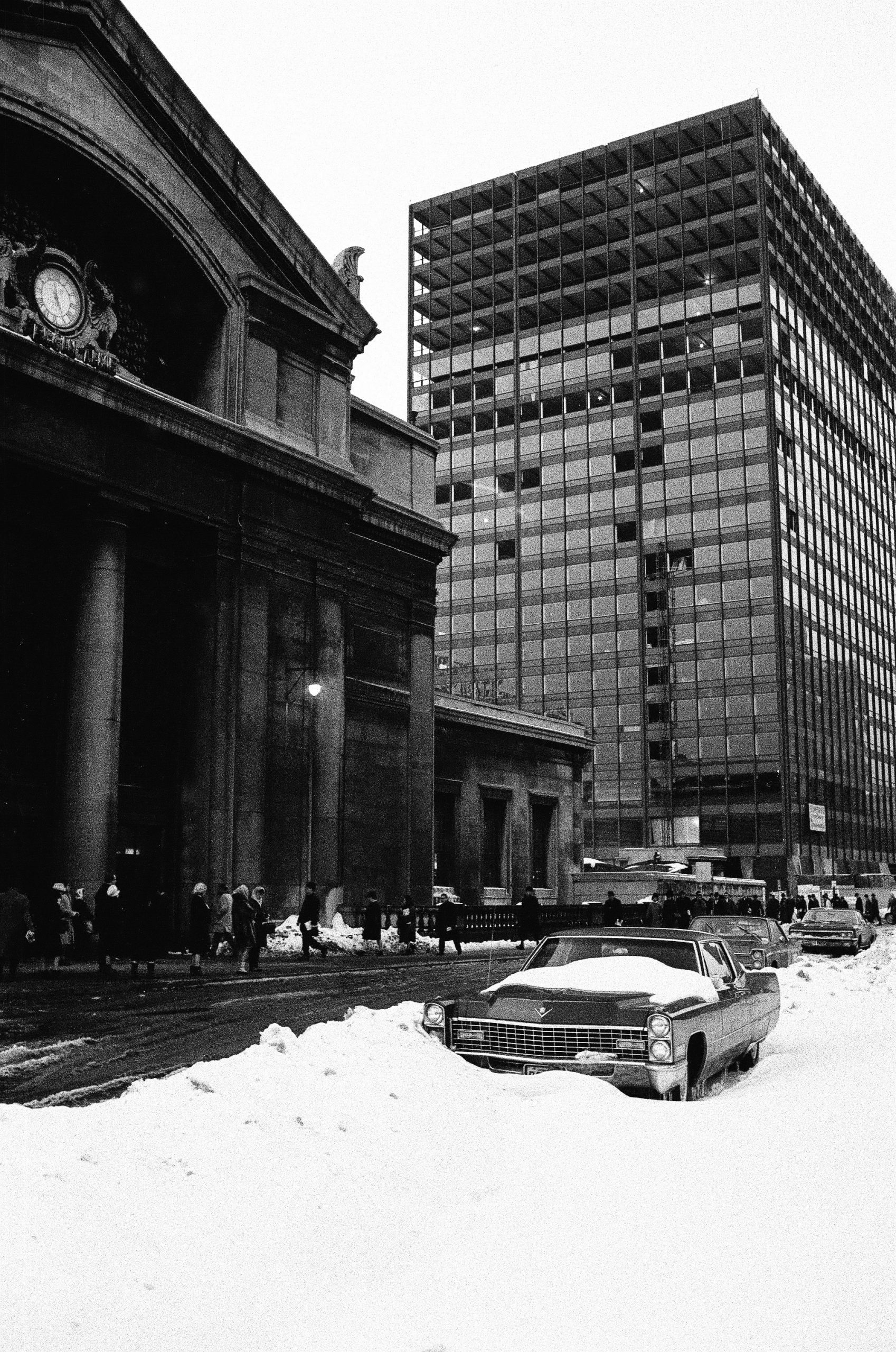

Digging out at Union Station, January 30, 1967; ST-11006892-0020, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM, Don Bierman, photographer

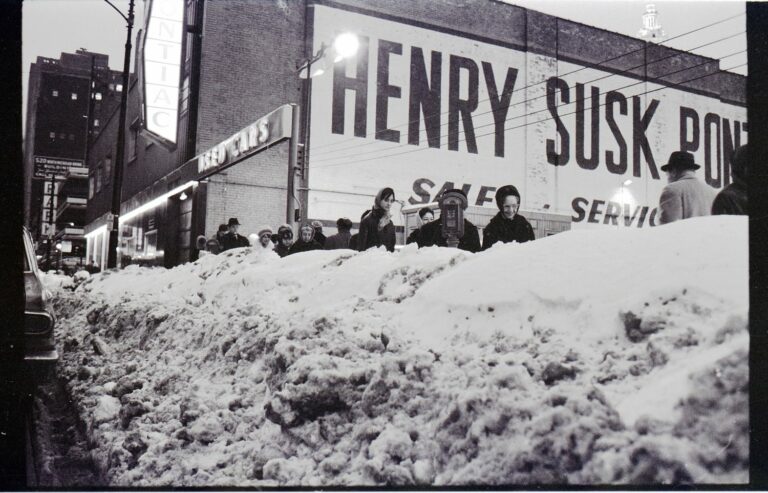

Commuters walk amid snow piles at Grand Avenue and State Street, February 2, 1967. ST-17100061-0002, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

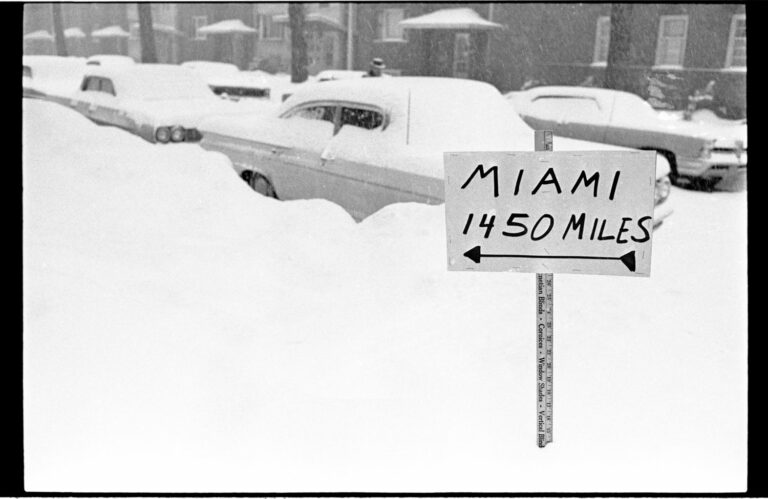

A sign attached to a yardstick in the snow, February 5, 1967. ST-17101329-0003, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Additional Resources

- In May 1967, Studs Terkel discussed the January snow-in with interviewees, who talked about how human interaction differs during a blizzard than on a clear day.

- Don Bierman for the Chicago Sun-Times documented the crowd in Union Station in the days following the blizzard.

- See more photographs of the aftermath of the blizzard at CHM Images.

Last week, noted Chicago historian, teacher, mentor, author, and civil rights leader Timuel Black died at the age of 102. Here, Warren Chapman, the second vice chair of the Chicago Historical Society’s board of trustees, and John Russick, CHM senior vice president, reflect on Black’s life as well as his work and impact on the Chicago History Museum.

“I never set out to make history, I just wanted to make things better for the people in the community.”

Warren Chapman recalls Timuel Black making that statement during an impromptu conversation in 2018. Whether intentional or not, Tim’s life became interwoven with history during the past 102 years.

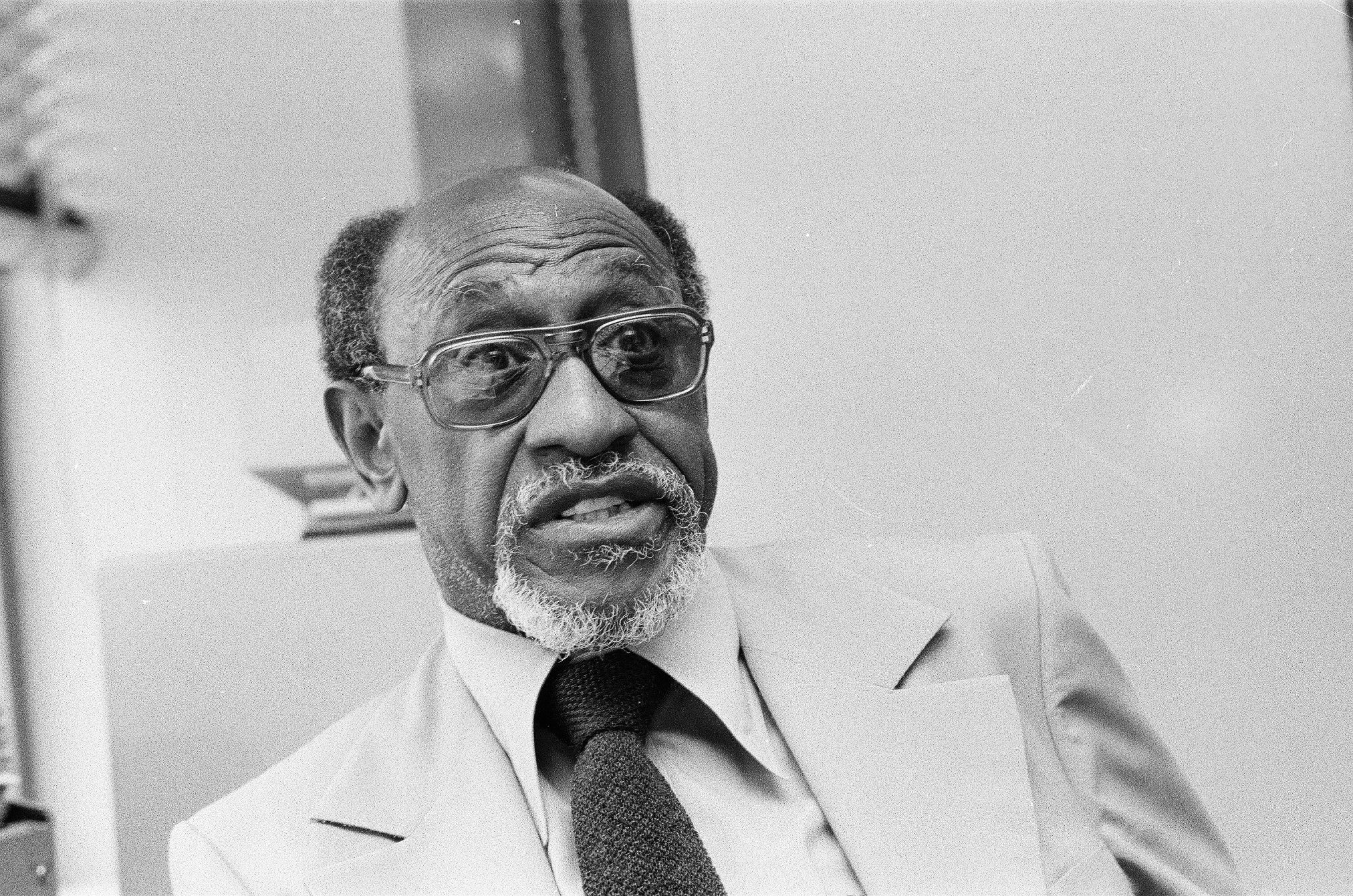

Timuel Black, Chicago, July 13, 1978. ST-70000678, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

He was born in Birmingham, Alabama, on December 7, 1918—right after World War I, in the middle of the influenza pandemic, and on a date that would later become synonymous with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. His family moved to Chicago in the summer of 1919, which would be remembered as the “Red Summer” for the number of racial riots that occurred across the United States, including in Chicago. This period was part of a larger movement called “The Great Migration.” During this time in the early to mid-twentieth century, African American families and individuals moved to northern cities like Chicago in order to escape the oppressive, restrictive environment that existed in the Jim Crow South. Later in life, Tim was able to capture the valuable experiences and skills these people brought with them, including their hopes and dreams for themselves, their children, and those who followed in future generations.

Through his writings and storytelling, Tim was able to bring to life the faces, voices, and melodies of the people he met, grew up, and worked with over the years. As Chapman recalls: “I remember Tim commenting on several occasions that he wanted to ‘share those voices with the world and in particular with our children and future generations, so they will be able to hear what I learned and know what once was known not only to me but the entire community as well.’”

Timuel Black (right) and Zenobia Johnson-Black (second from right) with two representatives from Edwards Dual Language & Fine and Performing Arts IB School accepting the Timuel Black Teacher of Excellence Award at the Chicago Metro History Day’s (formerly Chicago Metro History Fair) SPARK Awards ceremony at the Chicago History Museum, May 21, 2019. Photograph by CHM staff

A recipient of the Museum’s prestigious John Hope Franklin Making History Award for Distinction in Historical Scholarship (2006) and the namesake of the Timuel Black Teacher of Excellence Award, Tim helped guide the Museum, beginning in the 1980s, as it sought to build its collection to share the stories of a wider range of communities and people. One personal contribution was a donation of select papers to the Museum that pertain to the civil rights movement in education.

In the fall of 1998, staff of the Chicago History Museum arrived at the Black home to photograph Tim in his library for an exhibition about older Chicagoans still working and contributing to the city. The project was inspired by the work of David Isay and featured four other remarkable Chicagoans, including Carlos Cortez, Harue Ozaki, Florence Scala, and Art Shay. The portrait of Tim was staged and shot by Shay, who served as both a subject of the exhibition and the photographer. Tim turned 80 just a few weeks later. He was a perfect fit for the project, an older Chicagoan who made history many times over and was still at it.

Timuel Black talks about the history of Bronzeville during the unveiling of two bronze obelisks at 35th and State Streets by the Bronzeville Merchants Association, Chicago, September 24, 2009. John H. White/Chicago Sun-Times © 2009 Sun-Times Media, LLC. All rights reserved.

Moreover, this effort was in large part inspired by his work to include marginalized voices in the historical narrative. His books, Bridges of Memory: Chicago’s First Wave of Black Migration (2005) and Sacred Ground: The Chicago Streets of Timuel Black (2019), provided new and profound perspectives on the Black experience in Chicago, and the Museum wanted to work with him to open a new era of historical documentation. Tim helped the Museum as both a community collaborator and a scholar in our first collection of projects designed to share the histories of Chicago neighborhoods called Neighborhoods, Keepers of Culture (2004). Tim worked to make sure the Museum connected with the people who he felt best understood the history from a local perspective. He also convinced many of them to share their knowledge and their collections of photographs, documents, and artifacts with us. Needless to say, the Museum could not have done this important work in expanding the viewpoints contained in our collection without him.

In 2018, the Museum acquired the Chicago Sun-Times photography archive and began developing a book to feature the collection. Tim, a veteran himself, graciously agreed to let the Museum include an excerpt from his book, Sacred Ground, to accompany images of returning Black soldiers after serving in combat during World War II. The profound story of a veteran, returning to a country seemingly committed to denying him equal status, simmers with relevance in our times. Such is Tim’s greatest gift to us. His work and the memories he shared are valuable not just in our time, but will grow in significance as the Museum continues with the challenging work of writing a better and more inclusive story of our city and our country.

Tim passed away on October 13, 2021, at age 102. He remained an advocate for including the experiences of all people in our historical narratives, specifically the Black experience, throughout his life. As Charles E. Bethea, the Museum’s Andrew W. Mellon Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs, said when he heard the news, future historians will mention Tim’s name in the same breath with visionaries such as W.E.B. Du Bois and Carter G. Woodson.

Further Reading

- “Timuel Black, historian, civil rights activist, dies at 102,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 13, 2021

- “Chicago civil rights legend Timuel Black dies at age 102,” Chicago Tribune, October 13, 2021

- “Timuel Black, Strategist and Organizer for Black Chicago, Dies at 102,” New York Times, October 17, 2021

The Chicago History Museum joins the chorus of voices expressing our great sense of loss with the passing of historian, teacher, mentor, author, and civil rights leader Timuel Black. Like so many who have worked to understand the full and complex history of Chicago and its diverse communities, the Museum benefited greatly from our close relationship and regular contact with Tim. A recipient of the Museum’s prestigious John Hope Franklin Making History Award for Distinction in Historical Scholarship and the namesake of the Chicago Metro History Fair’s Timuel Black Teacher of Excellence Award, Tim helped guide the Museum as we sought to build our collection in order to share the stories of a wider range of communities and people. His books, Bridges of Memory and Sacred Ground: The Chicago Streets of Timuel Black, provided new and profound perspectives on the Black experience in Chicago.

Tim’s positive attitude and generosity was legendary, and our staff, past and present, benefited from his knowledge, insights, creativity, and seemingly boundless energy. He made a donation of his papers to the Museum in 1975, which are typically available to researchers in the Abakanowicz Research Center.*

The Museum plans to develop a feature on Tim and his legacy to be published in a future issue of Chicago History magazine.

*The Russell L. Lewis Jr Research Collections Facility is currently being renovated. This facility houses the Museum’s 23,000 linear feet of archives and manuscripts. Archives, manuscripts, and maps with the exception of some small collections, are unavailable to researchers through early 2022

In this blog post, CHM intern Rebekah Otto reflects on her experience working on CHM’s ongoing Afro-American Patrolmen’s League Oral History Project.

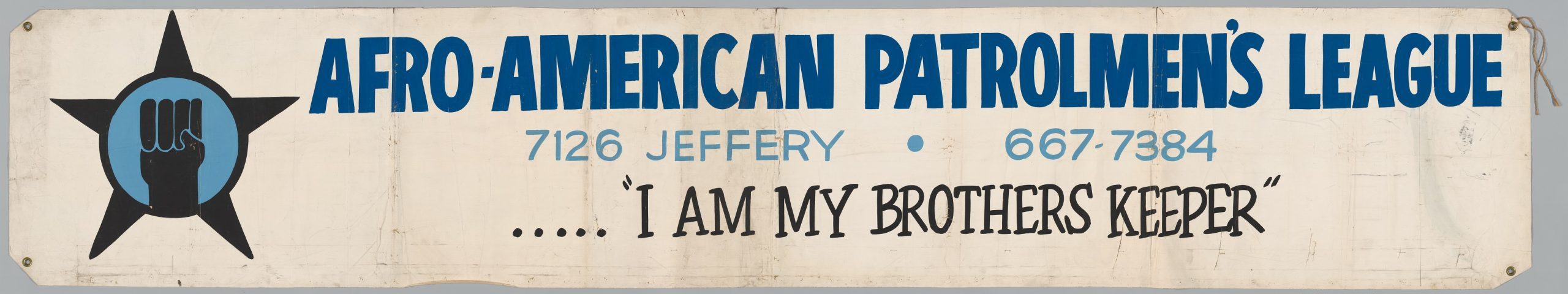

AAPL vinyl banner that reads, 1961–68. CHM, ICHi-170336

When I accepted the Black Metropolis Research Consortium’s Archie Motley Archival Internship offer, I had a vague understanding of my project. I was thrilled to be working in a museum for the first time and engaging with work I love—Black stories. At that time, the goal for the Afro-American Patrolman’s League (AAPL) project was to conduct six oral history interviews and at least one transcription by the end of my eight-week program. While I was unable to officially interview former AAPL members over Zoom due to scheduling conflicts, briefly connecting with them and learning pieces of their stories (through phone calls and research) was extremely worthwhile.

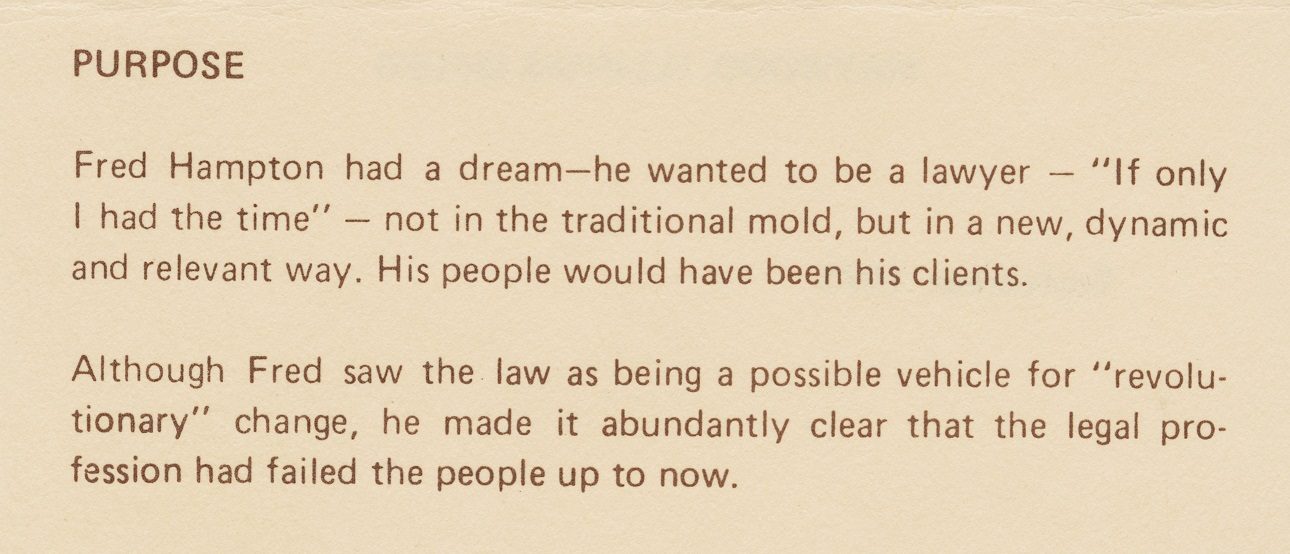

For the first few weeks, my primary task was research. My fellow project intern and I gathered as much relevant information on the AAPL as we could find in CHM’s archival materials and additional resources. We read a series of articles discussing policing and Chicago in the 1960s and ’70s. From there we found additional resources overviewing key historical events that directly engaged with Black policing, Chicago policing, and community activism. A few key examples were the assassination of Fred Hampton, the 1968 Democratic National Convention, the trial of the Chicago Seven, and more. Studying the political climate of Chicago helped us develop a framework for understanding the organizational structure of the AAPL. This research bolstered our understanding of the context of potential interviewees and assisted in developing interview questions and strategies to facilitate robust and efficient conversations.

Section from page 1 of an information card for the Fred Hampton Memorial Legal Assistance Scholarship Fund, September 1975. CHM, ICHi-173738-001

In addition to crafting interview questions, we discussed strategies to adapt oral history interviewing to pandemic times. These conversations helped us think differently about how COVID-19 uniquely impacts oral histories that engage with trauma and race-based violence. They reminded me of some impactful encounters I was able to have this summer in the form of informational interviews with CHM staff, where I asked about challenges they face in doing archival work. As with oral history interviews, archivists can encounter sensitive materials from marginalized people that require additional care and consideration.

Project archivist Donna Edgar described her current project as the “the basement mysteries,” which centers on uncovering documents left in the Museum basement. At times she stumbles upon treasures or fragments that belong in a larger collection while at other times, not so much. When I asked her how she stays motivated, she said that while so many “different cultures [have been] lost on the shelf,” her work allows her to unbury them, advocate for them, and help them find a home. Donna’s interview echoed the zest and candor of CHM archivist Angela Solis. Her journey into the world of archives was unexpected, yet in this work she has found immense purpose. Like Donna, Angela sees her work as shining a light on stories that face obstacles in getting onto the shelf: “My vocation is helping those stories get told . . . and helping them last.” While this internship was met with challenges, the connections I made with others led me to think critically not only of the stories we tell but also how we obtain, protect, and remember those stories.

If you were a former member of the African American Patrolmen’s League and would be interested in sharing your story, please contact us at 312-642-4600 or through our Collection Donation Form.

Additional Resources

- Read more blog posts about the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League

- Visit the Chicago History Museum’s Abakanowicz Research Center

In this blog post, CHM intern Kirsten Lopez shares what she learned while preparing to interview a retired Afro-American Patrolmen’s League member as part of an ongoing CHM oral history project.

During my summer 2021 internship, I had the opportunity to work on CHM’s ongoing Afro-American Patrolmen’s League (AAPL) Oral History Project, which is focused on collecting the stories of former AAPL members to create a more diverse collection. In preparation for the culminating interview with a retired AAPL member, I spent the first few weeks of the internship learning about the organization and acquainting myself with the digitally available material from the AAPL archive housed at CHM. While I became familiar with the names of AAPL founders and Chicago political players, I did not come across the name Wylola Evans, the civilian member I would be interviewing. I wondered how she was connected and what type of work she did.

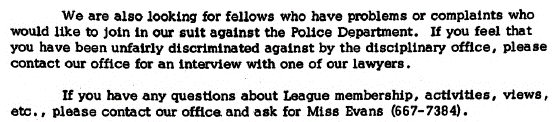

As it turns out, Evans was not only the League’s first full-time employee, but she also supervised the entire AAPL office and was the primary point of contact for “League membership, activities, views, etc.” according to the League newsletter, The Grapevine. “Etcetera,” I came to learn, meant anything from attending National Black Police Association conferences to printing and distributing event posters around the city; from securing sponsors to answering citizens’ calls to the AAPL’s Police Brutality and Legal Referral Service. The “long, crazy hours” and “little to no pay” were worth it, Evans told me, “Because we were interacting with the community.”

I went back into the archive and started looking for Wylola Evans.

Instructions to “ask for Miss Evans” at the AAPL office. The Grapevine, 1972. African American Police League (Chicago, IL) records, 1961–88. Box 164.8.

Announcement for the 3rd Annual National Black Police Association (NBPA) convention in Boston, Oct. 10–14, 1975, with a reminder to “ask for Miss Evans.” African American Police League (Chicago, IL) records, 1961–88. Box 64.8.

Among the newsletters and editorials, I found two occasions in which members were directed to “ask for Miss Evans” when they called the office. Evans, it became clear, was at the very center of AAPL activity, but she was largely absent from the literature and archival materials that are currently publicly available.

It seems timely to think about all the work that goes into achieving historical change and how it is mostly done without fanfare and out of the public eye. Indeed, during my time at CHM I witnessed firsthand how much time and consideration is taken by Museum staff to maintain its collections and ensure a continuous offering of events and exhibitions for the public.

The work of cataloging, moving boxes, fighting mold, and updating metadata that allows institutions like CHM to preserve and shed light on the everyday stories that make history relevant is unglamorous but, like the work of AAPL’s civilian staffers, essential. And, in keeping with AAPL’s stated commitment to being “available to many individuals and community organizations, giving them advice on their legal rights, and in participating in solving community problems,” it feels only right to show appreciation for the invisible work that made such a transformative relationship between police and citizens possible. As the very first AAPL newsletter urges members, “REMEMBER: THE LEAGUE IS YOU.” The practice of oral history aims to capture the lived experiences that might otherwise remain overshadowed. And so, let us take this lesson from Wylola Evans that history is in the hidden work of everyday people.

Guest editorial in the February 1974 issue of The Grapevine. The bold text between segments reads “AAPL Thanks to you it’s working.” This issue featured the transcript of CPD Deputy Chief of Patrol George T. Sims’s testimony regarding discriminatory practices under Superintendent James M. Rochford. African American Police League (Chicago, IL) records, 1961–88. Box 64.8.

Excerpt from the AAPL’s Newsletter #1, published November 14, 1968. African American Police League (Chicago, IL) records, 1961–88. Box 164.8.

If you were a former member of the African American Patrolmen’s League and would be interested in sharing your story, please contact us at 312-642-4600 or through our Collection Donation Form.

Additional Resources

- Read more blog posts about the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League

- Visit the Chicago History Museum’s Abakanowicz Research Center

Print out all four activities (download complete kit here) and enjoy learning more about the fire through drawing, writing, and crafting in response to amazing images and documents from the museum’s collection.

You can also choose the activities that are the best fit for your family and only print those. The estimated time for each activity is approximately 30 to 45 minutes.

Activities are in English and Spanish. | Las actividades son en inglés y español.

- Introduction to the kit and additional resources.

- Artifact Detective: Use your observation skills to guess what these melted objects were before the fire! Recommended for ages 6 and up. Three pages, but the last page will need to be printed for each child.

- Kid’s Voices Matter! Justin’s Letter: Learn the story of how Justin, his family and his goat survived the fire through the letter he wrote and picture he drew. Then have fun choosing a way to document your own family memories! Recommended for ages 6 and up. Three pages.

- Make Your Own Firefighter Hat: Compare historic and modern firefighter helmets. Then make your own! Recommended for ages 3 (with adult help) and up. Three pages, but the last page will need to be printed for each child.

- The Burnt District Today. Mapping Activity: Use historic and modern maps to trace the path of the fire and mark important places in your own life! Recommended for ages 10 and up. Four pages.

Use this fun gallery guide as you explore the City on Fire: Chicago 1871 exhibition. Learn more about the exhibition at chicago1871.org.

We look forward to welcoming you to the Museum!

Gallery Guide (English) PDF | Guía de la Galería Familiar (Español) PDF

Featured in our City on Fire: Chicago 1871 exhibition is a 40-feet-long painting study created as a guide for a larger Chicago Fire Cyclorama painting, which was displayed in Chicago in 1892-93 in a round building constructed for visitors to have an immersive experience. You can take an in-depth look at the painting study in our latest Chicago00 experience: 1871 Chicago Fire, created for the 150th anniversary of the Great Chicago Fire.

Here, Carl Smith, Franklyn Bliss Snyder Professor of English and American Studies and Professor of History, Emeritus, at Northwestern University, writes about this history of cycloramas and how the Chicago Fire Cyclorama came to be.

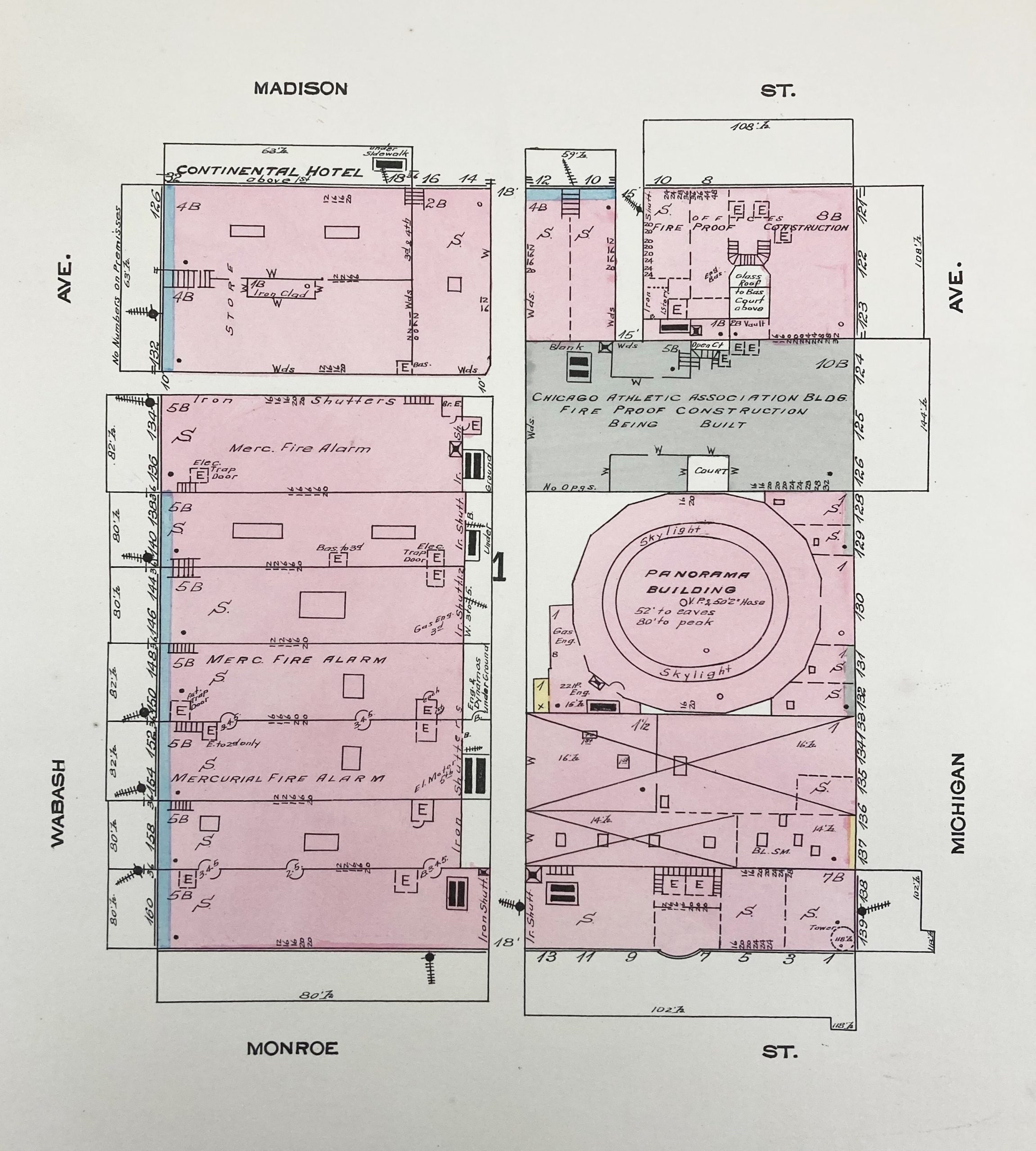

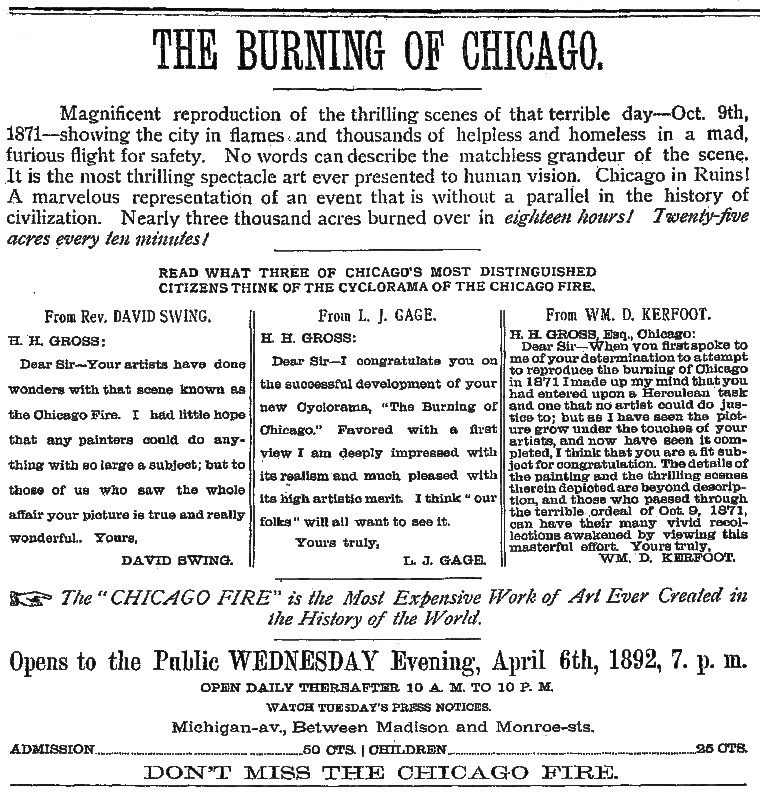

Large as it is, the Chicago History Museum’s painting of the Great Chicago Fire examined here is a preliminary version of one ten times as big. At approximately fifty by 400 feet, the latter painting was almost a third as wide as a football field and forty feet longer. It was on display to paying viewers from the spring of 1892 to the autumn of 1893 in a specially constructed building on Michigan Avenue between Monroe and Madison Streets in downtown Chicago. The main feature of the building was its capacious central circular room, sixty feet high and almost 130 feet in diameter, on whose wall the enormous painting was mounted. A stairway led visitors to a platform in the center of this room, where they found themselves surrounded by what advertisements in the Chicago papers proclaimed was “a marvelous representation of an event that is without parallel in the history of civilization.”

The scale of this colossal artwork, its 360-degree vista with multiple vanishing points, and its meticulous attention to detail, combined with a seamless visual transition between visitors and the painting, were all intended to simulate the experience of being present at the actual fire. A successful cyclorama such as this one—much like a 3D film or a set of virtual reality goggles—provided an exciting and even unnerving visual and psychological experience.

By the 1890s, cycloramas were a common form of metropolitan entertainment more than a century old. The earliest examples appeared in London in the late 1780s, quickly followed by cycloramas in cities across Europe and in the young American republic. Favored subjects included contemporary local settings but usually places and moments more distant in space and time. Among the latter were natural wonders like Niagara Falls, dramatic scenes from the Bible like the Crucifixion, and, most of all, great historical events such as the destruction of Pompeii and especially famed sea and land battles.

The heyday of the cyclorama in the United States was the last three decades of the nineteenth century, by which time the rapidly urbanizing nation contained a substantial number of cities with enough people who had the discretionary income and time needed to support attractions that were costly to produce. Between 1850 and 1880, the number of US municipalities with 100,000 or more people jumped from six to twenty. By 1900 there were thirty-eight such cities, half of them with a population of over 200,000.

The battles of the Civil War, fresh in memory, were the most popular subjects for cycloramas in the United States. Americans could transport themselves to the epic engagements at Bull Run, Vicksburg, Missionary Ridge, Shiloh, Fort Donelson, Chattanooga, and Atlanta, and multiple versions of Gettysburg, not to mention the clash between the ironclad ships Monitor and Merrimack. Soon post-Civil War military encounters, notably the 1876 defeat of Custer and his cavalrymen by the Lakota and other Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains, would join the cyclorama repertoire.

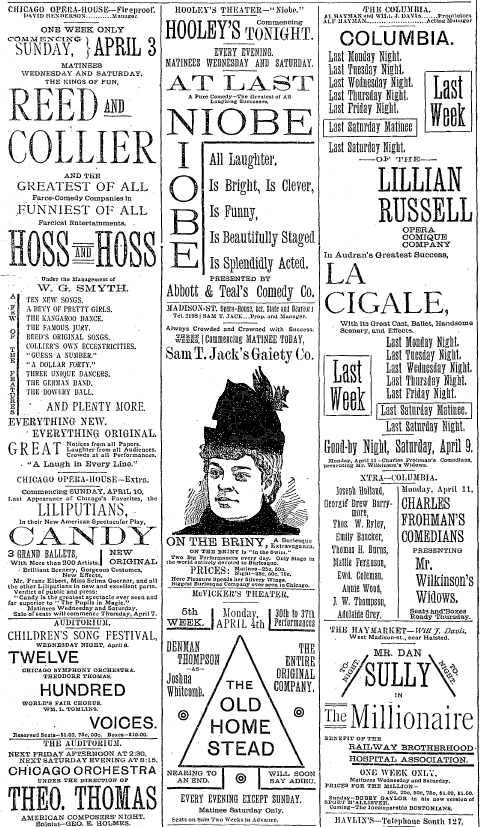

A single cyclorama remained on view in a particular venue for several months, perhaps even a year or longer if it kept drawing customers. A single cyclorama would often “play” in a scheduled series of cities. Amidst the hurly-burly of urban cultural life, cycloramas and related jaw-dropping visual productions competed with many other forms of staged entertainments. At the time the Chicago Fire Cyclorama opened, local theatergoers’ options included the Chicago Orchestra conducted by maestro Theodore Thomas, Gilbert and Sullivan’s H.M.S. Pinafore, the Lillian Russell Opera Comique production of La Cigale, the Cornell University Glee and Banjo Clubs, Haverley’s Minstrels, and trained animal shows such as Kohl & Middleton’s Educated Equines. There were also sporting events and a range of museums, whether of painting and sculpture, animal and plant specimens, or historical artifacts and oddities that were frequently as dubious as they were fascinating.

Theater advertisements, Chicago Tribune, April 4, 1892.

As one of the country’s biggest cities and the center of its transportation and communications network, Chicago was a prime location for cycloramas. The first cyclorama in Chicago was apparently a view titled Paris by Moonlight mounted in 1874 in the immense Inter-State Exposition Building. With a quarter million square feet of floor space, that structure had been erected the year before for a trade fair whose main purpose was to declare that Chicago had indeed risen from the flames. Located along the east side of Michigan Avenue and centered on Adams Street, it would host many other events and activities until it was torn down in the early 1890s to make way for the Art Institute of Chicago, which, much expanded, occupies the site today.

nter-State Exposition Building at Michigan Avenue and Adams Street, c. 1890; J. W. Taylor, photographer. CHM, ICHi-064394.

By the mid 1880s there were three permanent cyclorama buildings in downtown Chicago. Two were across the street from one another, on the southeast and southwest corners of Wabash Avenue and Hubbard Court, now Balbo Street. The one to the west hosted the most enduring cyclorama in Chicago—one of French artist Paul Philippoteaux’s several renditions of the Battle of Gettysburg. When the Chicago Fire Cyclorama opened in 1892, the Gettysburg painting had been on display for a full decade. In the same ten years, the cyclorama building on the east side of Wabash Avenue had hosted The Siege of Paris, The Battle of Lookout Mountain, Jerusalem and the Crucifixion, and Niagara Falls.

Cyclorama Buildings at Wabash and Hubbard (with the rounds roofs), looking south, c. 1895–1900. CHM, ICHi-005715.

The Chicago Fire Cyclorama building between Madison and Monroe Streets on Michigan Avenue was six blocks to the north and one to the east of the venues on Wabash, on land owned by the family of mechanical reaper magnate Cyrus McCormick. It was erected in 1885 to host The Battle of Shiloh.

Fire Insurance Map showing location of the cyclorama building (here referred to as the Panorama Building) on Michigan Avenue between Monroe and Madison Streets. Block Book of Chicago, Rascher Insurance Map Publishing Co., 1893.

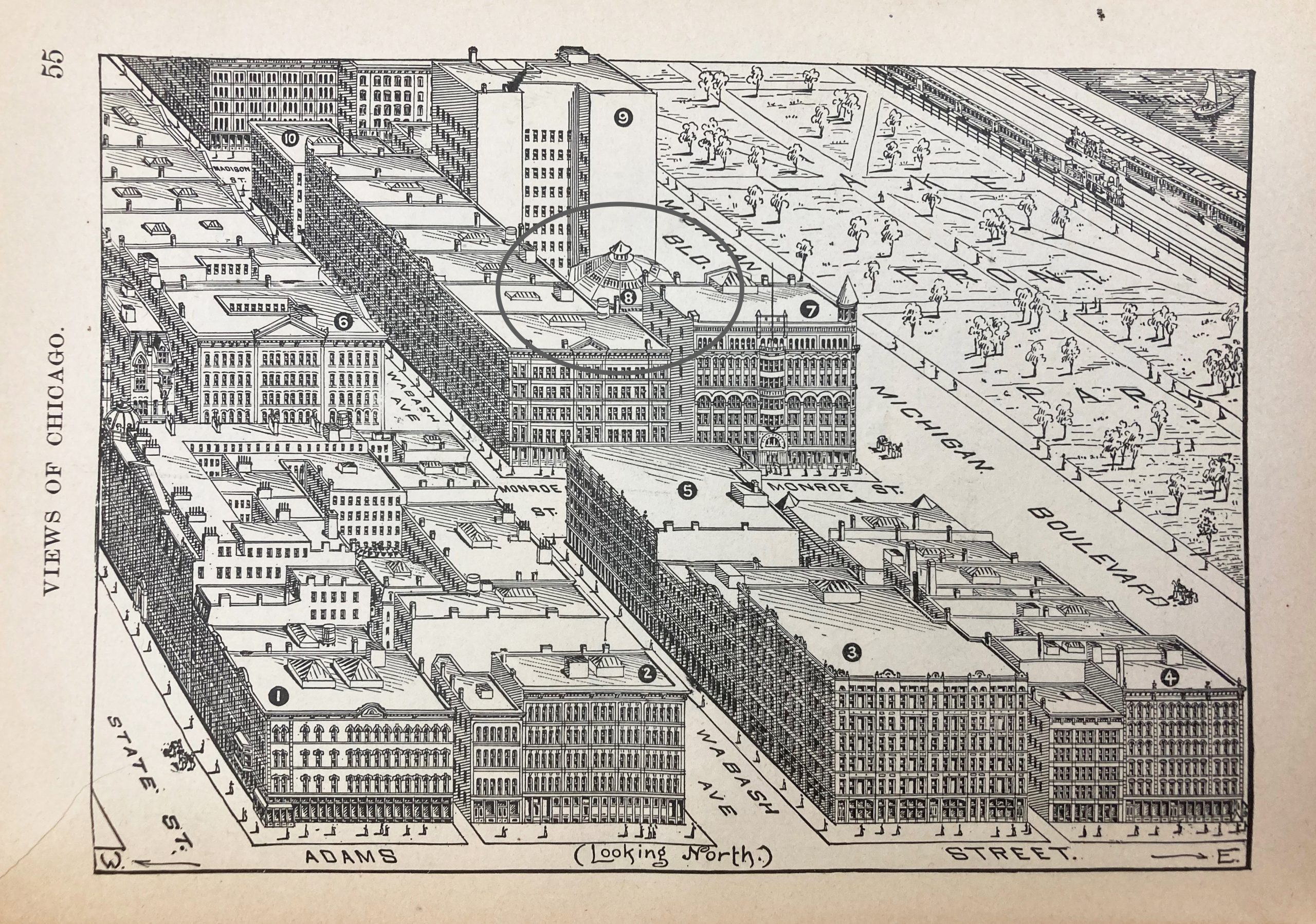

When plans were announced for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the certainty of a major spike in visitors to Chicago inspired backers of all sorts of entertainments to try to cash in. Rand McNally & Company’s Bird’s-eye Views and Guide to Chicago, published in 1893 in anticipation of travelers from around the country and world, stated that there were now five cycloramas in the city. During the run of the fair, there would be six. The three newer ones in addition to the three already downtown were in temporary quarters close to the main exhibition buildings of the Exposition, which were located along the lakefront between Fifty-Seventh and Sixty-Seventh Streets in Jackson Park.

View of Fire Cyclorama Building (in oval) from Rand McNally & Co.’s Bird’s-Eye Views and Guide to Chicago, 1893, p. 55.

On the Midway Plaisance, near such attractions as Carl Hagenbeck’s performing wild animals, the recreation of a street in Cairo, and the first Ferris Wheel, one could view cycloramas of the Hawaiian volcano Kilauea and the Swiss Alps. A few blocks away, at Stony Island Avenue and Fifty-Seventh Street, was The Battle of Chattanooga, whose opening was delayed when, in April, what was described as “a medium wind” blew down the flimsy structure intended to house it.

Hawaii Kilauea Cyclorama on the Midway, 1893. CHM, ICHi-092991.

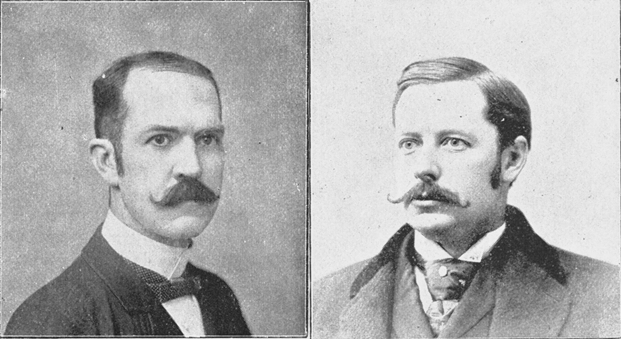

The entrepreneurs behind the Chicago Fire Cyclorama were Isaac N. Reed and Howard H. Gross, whose partnership included similar projects in Melbourne and London as well as Chicago. According to cyclorama scholar Eugene Meier, Gross had a hand in close to thirty cycloramas. Gross also oversaw the preparation of seven large paintings of scenes of California for the state’s Spanish colonial-style building at the Columbian Exposition.

It was Gross who in 1905 donated the smaller preliminary version of the painting owned by the Chicago History Museum. CHM’s records indicate that Gross did not give the painting directly but through prominent Chicago grain commission merchant Frank G. Logan. Logan was a collector both of Native American artifacts and items relating to John Brown and Abraham Lincoln. The Native American artifacts were exhibited by the Anthropology Department of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the Brown and Lincoln materials in the fair’s Illinois Building.

Logan accompanied the deed gift of the study with several legal documents. These documents reveal that the Chicago Fire Cyclorama Company filed its incorporation papers with the State of Illinois on April 13, 1891, and received approval on June 9. It gave its address as a building on Dearborn Street.

Daniel J. Hubbard, a real estate man whose office was in the same building, was officially the president of the company, though Gross was the driving force behind the production of the cyclorama. He was also by far the main investor. Of its 1,250 shares of stock, valued at one hundred dollars each, Gross owned 935. The two next largest backers, one of whom was Hubbard, owned only fifty shares. Another investor, with twenty-five shares, was pioneering professional baseball player and executive Albert G. Spalding.

Gross, Hubbard, Spalding, and the other owners stated that the purpose of their corporation was “to buy and sell, and to exhibit, Cycloramas, and particularly to exhibit a Cyclorama of the Chicago Fire of the year A.D. 1871, and for the purpose of conducting any other amusement or amusements, connected with such exhibition.”

Another document states that at a special meeting on January 18, 1892, the stockholders approved a doubling of the number of shares to 2,500 and of its valuation to $250,000. This figure was cited in newspaper advertisements that claimed the fire cyclorama was the “Most Expensive Work of Art Created in the History of the World.”

Isaac N. Reed (left) and Howard H. Gross (right), from A Story of the Chicago Fire, by Rev. David Swing, 1892.

Reed and Gross hoped to begin admitting viewers to the Chicago Fire Cyclorama on October 11, 1891, almost exactly twenty years after the fire. When they missed this deadline, the reason given in the newspapers was “the difficulty in procuring data” on the fire and “the absolute necessity of exactness of detail in the drawing.” Gross claimed that he had spent more than a year gathering information, in which time he had collected 8,500 photographs and conducted interviews with some 1,300 people, at a cost of $120,000. To obtain these resources, he placed ads in the local newspapers appealing to those who had experienced the fire. He also purchased photographs from P. B. Greene, one of the several local photographers who marketed stereographs of the disaster. He appears to have tried unsuccessfully to include Catherine O’Leary in his interviews. All this effort, he insisted, ensured the fidelity of the painting to its subject. Gross challenged any survivor of the fire “to point out a single detail which was not historically and architecturally accurate.”

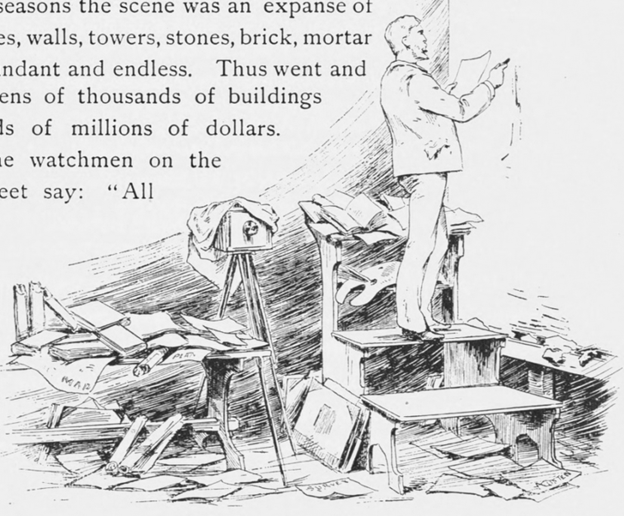

By the late nineteenth century, cyclorama makers followed a standard set of procedures and techniques. Working from the documentary records that Gross had assembled, artists created a one-tenth scale version, of which the Chicago History Museum’s painting is an example. At this stage, they worked out compositional issues and how they wished to handle color and light. The next step was to transfer this version in detailed outline to the full-size cyclorama. To accomplish this, they divided the former into a grid of 100 squares and photographed these squares onto glass plates. They then projected these images at ten times actual size onto the much larger final canvas (or linen) and used these projections to trace the smaller version on it. As was the case with the Chicago Fire Cyclorama, the artists made numerous alterations between the preliminary and the final version, though not in the overall composition.

To reach everywhere on the larger surface, artists worked from several multilevel platforms that moved along a set of circular tracks in front of the painting. Just hanging or taking down the enormous work was a daunting task, requiring not only brute strength but also a certain delicacy, since cycloramas, which weighed several tons, were easily damaged. There were many injuries, some fatal, most attributable to falls from or the collapse of a platform.

Artist working on the Chicago Fire Cyclorama, from A Story of the Chicago Fire, by. Rev. David Swing, 1892. Note the reference books, drawings, and camera, all of which were important to the creation of a cyclorama.

The artists treated the floor area between the center spectators’ platform and the painting into a stage set of sorts, using landscaping and props in constructing a three-dimensional foreground designed to blend into the two-dimensional painting on the wall. In addition, they hired live models for the drawings of figures. They also arranged lighting to create the most dramatic effects. Many cyclorama buildings had skylights, but cyclorama makers also skillfully employed artificial illumination. By the close of the nineteenth century this meant electric lights. The promoters might add live or, later on, recorded music. A guide or even an orator might be on hand to enrich the viewers’ visit.

Like other cyclorama impresarios, Reed and Gross recruited a talented group of artists to recapture the fire in all its vivid intensity. Salvador Mége of Paris and Edward James Austen of London, both experienced cycloramists, laid out the composition and decided on the colors employed. Austen suffered serious injuries in a fall from a platform, which contributed to the delay in completing the project. Oliver Dennett Grover, a faculty member of the School of the Art Institute (which dates to 1879), was responsible for the many figures in the painting, with assistance from Charles Corwin and Edgar S. Cameron, who was also an art critic for the Chicago Tribune. Paul Wilhelm, a Chicagoan from Dusseldorf, Germany, did much of the foreground work, including the vessels on the main branch of the Chicago River. The horses were done by animal painter Richard Lorenz, a German-born artist based in Milwaukee. Another Frenchman, Albert Francis Fleury, was credited for the structures by the lake and river, while C. H. Collins’s hand is seen in the blocks of buildings destroyed by the fire.

Some of these artists accomplished other important and enduring things in Chicago besides their contributions to this and other cycloramas. Fleury, who also was associated with the School of the Art Institute, executed many superb drawings of the Chicago cityscape and painted the large murals on the sides of the interior of the Auditorium Theatre that accompany architect Louis Sullivan’s odes to spring and fall inscribed on these walls. Corwin would later specialize in another form of virtual reality, the backgrounds of dioramas in the Field Museum, whose current building opened in 1921. William Leftwich Dodge, who had studied with another fire cyclorama artist, Jean-Léon Gérôme, at the École des Beaux Arts in Paris, also did murals for the Administration Building at the Columbian Exposition (and the Library of Congress in Washington, DC).

The Chicago Fire Cyclorama opened at 7:00 p.m. on Wednesday, April 6, 1892. Notices stated that the painting could be viewed twelve hours a day, from 10:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m., seven days a week. Regular admission was fifty cents (half that for children), the same price as entry to the entire World’s Columbian Exposition main grounds or a single ride on the Ferris Wheel. This was at a time when a laborer might earn five or six dollars a week. Reed and Gross ran large advertisements in the daily papers declaring their latest marvel “the most thrilling spectacle art ever presented to human vision.”

Advertisement for the Chicago Fire Cyclorama, Chicago Tribune, April 3, 1892.

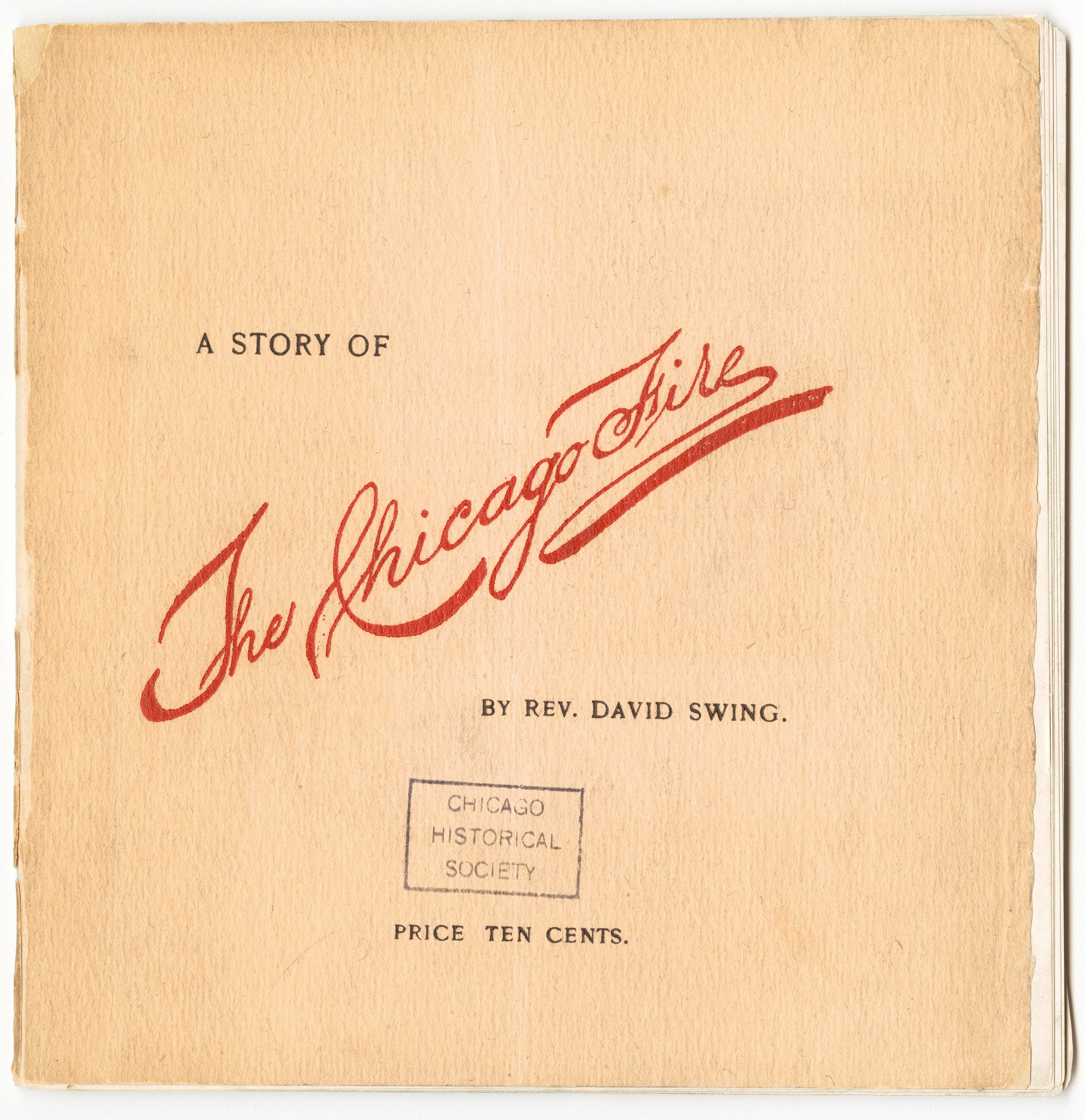

In addition to paying their admission, visitors could spend another ten cents on an illustrated souvenir booklet. Titled The Story of the Chicago Fire, it consisted mostly of a personal account of the disaster by the Reverend David Swing, one of the most popular ministers in the city. This was followed by factoids pertaining to the fire (“The loss in property was a million dollars every five minutes!”) and the painting, as well as profiles of Reed, Gross, and their artists. The booklet calculated that the almost 20,000 feet of surface area was covered with nearly two tons of paints and oils, adding, “The work, if it had been done by one man, would have required over twenty years to complete.”

Cover of A Story of the Chicago Fire, 1892. CHM, ICHi-1788417-001.

The fire cyclorama remained on display for some nineteen months, until the Columbian Exposition closed its doors at the end of October 1893. It was forced to suspend operations for a short period when in November 1892 the neighboring Illinois Athletic Association (also called the Chicago Athletic Association, and now the Chicago Athletic Association Hotel) next door caught fire. In battling the blaze, the fire department demolished the Fire Cyclorama building’s glass roof and flooded its interior, forcing considerable repairs. According to one reporter, “The boys mistook the painting for the real fire.”

The Chicago Fire Cyclorama appears to have done a decent but not remarkable business. The Rand McNally & Co. guidebook to the city stated that the number of patrons in the first year was 144,000, but this is not authoritative and might be based on an exaggerated claim by the promoters. Given that many visitors were children, who were admitted at a discount, it seems likely that the enterprise either made little money or even failed to break even. In any event, Gross and Reed did not keep it open after the close of the Columbian Exposition.

Gross proposed another cyclorama, this one a grand vista of the Exposition. Backers of the proposal included noted Chicago architect Daniel Burnham, who had been the fair’s highly praised director of construction; financier and future US Treasury Secretary Lyman Gage; railroad car manufacturer George Pullman; Chicago Tribune owner Joseph Medill; and Bertha Honoré Palmer, wife of hotelier Potter Palmer, benefactor of the Art Institute and the leader of Chicago society.

But by the mid-1890s, after about a decade in the cyclorama business, Gross left it to pursue not only other commercial ventures but also several civic-minded undertakings. Throughout his career he moved from one project to another or was engaged in a few at the same time.

When Chicagoans learned the Fire Cyclorama’s days were numbered and that there was talk of moving it to London, some called for finding it a permanent home in the city. The leading suggestion was to place it in a building in one of the city’s parks—the West Side’s Garfield Park was the most frequently mentioned candidate—where admission would be nominal or without charge. Nothing came of this. In 1900 Gross offered to donate the cyclorama on the condition that it be properly housed and free to the public. Again, there was a proposal to locate it in a handsome new beaux arts building in a park, but this, too, went nowhere. The mammoth fire cyclorama painting remained rolled up in storage near Gross’s home a few blocks west of the South Side’s Washington Park. In 1913, by which time it probably had deteriorated a great deal, it was sold as scrap to a junk dealer for two dollars.

By then the era of the cyclorama had passed. Over the previous decades artists and inventors were developing even more arresting visual displays. Of special interest is something called the Scenograph, created by Fire Cyclorama artist Edward James Austen, which opened in the summer of 1894 in New York’s Madison Square Garden before moving to Boston. Its central subject was Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition (it is not clear whether this had any connection to the project in which Gross had been involved). The Scenograph was not a 360-degree vista but a broad bird’s-eye view, as if from a balloon 6,000 feet out into the lake and 600 feet in the air. As a result, it encompassed not only the fair, but also metropolitan Chicago and the surrounding countryside.

The Scenograph received rave reviews in the New York and Boston papers. Critics noted how successfully Austen overcame the major liability of the cyclorama—its static quality. Working wonders with lighting effects, Austen somehow made the sun rise and set as boats glided across the lake and trains bustled along their tracks.

There was no way cycloramas could compete with the latest big step in virtual reality, the motion picture, which existed in primitive form by the early 1890s. Within a decade after the Chicago Fire Cyclorama closed, the Chicago firm of Essanay Studios, which employed Charlie Chaplin and numerous other silent film notables, was making movies downtown and planning a move to new facilities it would construct on Argyle Street in Uptown, which still stand.

Cycloramas continued to play in Chicago and other cities for a while, but most cyclorama buildings that did not close survived by finding other uses. They hosted political conventions, flower exhibitions, dog shows, religious revivals, boxing matches, bicycle races, and other events that needed large open interior space. In 1895 the structure that had presented the Chicago Fire Cyclorama, commonly called the Panorama Building, accommodated an exhibition of druggist’s products. The next year it presented a pure food show with all kinds of edible goodies. Soon dogs would disturb the cats at a household pet show held within its walls, which also contained the 1897 poultry and pigeon show sponsored by the National Fanciers’ Association of Chicago. One of the building’s final uses was as the site for the city’s grateful welcome to sailors returning from the war in the Philippines.

Shortly after that, Stanley McCormick, Cyrus’s youngest son, commissioned the top architecture firm of Holabird & Roche to build two buildings on the site of the Panorama Building and a third building just to the south. The three buildings, erected in 1898‒99, were originally leased to prominent wholesale millinery companies. The northernmost of the three, known as the Gage Building, was soon raised to its current height of twelve stories. Its ornamental enameled terra cotta façade, designed by Louis Sullivan, is one of the few buildings in Chicago on which he worked that are still standing.

The seven-story red building and the twelve-story building to its left now occupy the site of the Chicago Fire Cyclorama building on the west side of Michigan Avenue, between the University Club and the Chicago Athletic Association Hotel. Millennium Park is across the street. Photograph by Carl Smith.

Cycloramas did not completely disappear. CHM’s study for the Chicago Fire Cyclorama was evidently exhibited in Marshall Field’s in 1921 as part of the department store’s commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Great Fire. A recent count lists about three dozen cycloramas throughout the world. Extant American cycloramas include a relatively early example, artist John Vanderlyn’s 1818 view of Versailles. Originally exhibited in a building constructed in lower Manhattan, it now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum. Two others are in Atlanta, Georgia, and Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. They both are extensively restored nineteenth century paintings of the Civil War battles that took place nearby.

The website of the Battle of Atlanta calls it “one of America’s largest historic treasures.” It adds that the Atlanta History Center, where the painting is mounted, “uses this restored work of art and entertainment, and the history of the painting itself, as a tool to talk about the ‘big picture.’” The Battle of Gettysburg cyclorama calls it “the largest oil-on-canvas painting in North America.” Its website claims that its effect on the viewer is to create the illusion of being in the midst of the drama, “an immersive experience” that visitors describe as “moving,” “riveting,” and “breathtaking.” The same could be—and was—said about the Chicago Fire Cyclorama.

Special thanks to Gene Meier.

Further Reading

- Atlanta History Center, Cyclorama: The Big Picture

- Bernard Comment, The Painted Panorama (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999)

- Theodore R. Davis, “How a Great Battle Panorama Is Made,” St. Nicholas 14, no. 2 (December 1886): 99‒112

- Gettysburg Foundation, Gettysburg Cyclorama

- Ralph Hyde, ed., Dictionary of Panoramists of the English-Speaking World

- “Moving a Cyclorama,” Boston Daily Globe, December 7, 1890, 23.

- National Park Service, Cyclorama

- Stephen Oettermann, The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium (New York: Zone Books, 1997)

- David Swing, The Chicago Cyclorama (Chicago, 1892)