Latest Posts

Chicago, a city renowned for its architectural marvels and cultural richness, has a darker side to its history–one that unfolds through infamous true crime cases. In this blog post, Ayah Elkossei of the Chicago History Museum’s Abakanowicz Research Center (ARC) shares about the abundant resources for those fascinated by the city’s criminal past. Content warning: Some of the resources discuss heinous acts of violence and sexual assault, which may be distressing or triggering.

The newly available True Crime LibGuide is a digital treasure trove crafted by ARC staff to help you explore our holdings on the enigmatic world of Chicago’s criminal underbelly.

Al Capone leaving court during trial for tax evasion, Chicago, c. 1931. DN-0096927, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The LibGuide has five categories, which will guide users through the various entry points into true crime research. Starting with a list of Specific Cases, it delves into notorious trials that have left an indelible mark on Chicago’s history. From the chilling tales of notorious mobster Al Capone and serial killers, such as John Wayne Gacy, to the complex tapestry of political scandals, this section not only captures the attention of true crime enthusiasts but also serves as a valuable resource for those venturing into the depths of historical research methods. One of the highlights in this category is the Museum’s extensive material on the infamous duo, Leopold and Loeb.

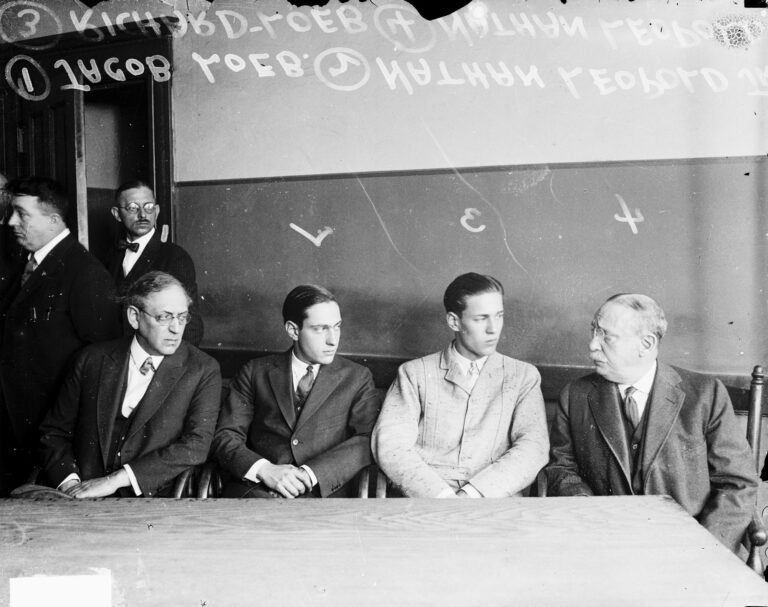

Jacob Loeb, Nathan Leopold Jr., Richard Loeb, and Nathan Leopold Sr. sitting at a long table in a room in Chicago, before Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold Jr. went on trial for the murder of Bobby Franks, June 2, 1924. DN-0078038, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

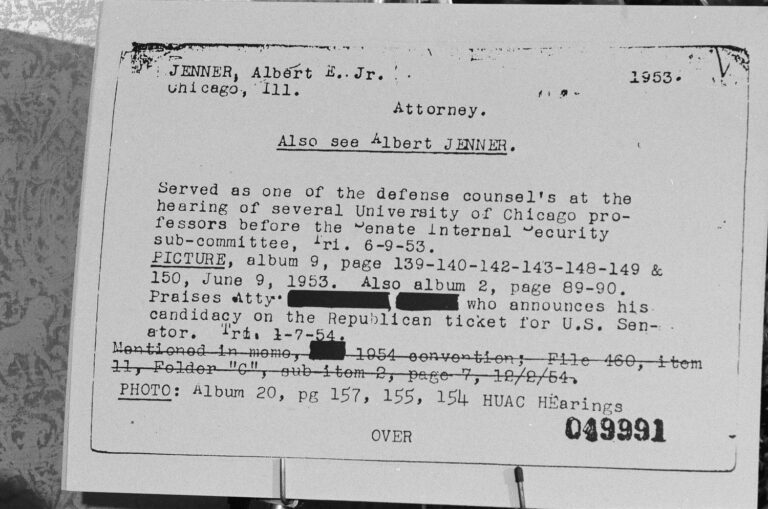

In the Archives and Manuscripts section, you can explore primary sources such as firsthand accounts and historical documents. It is a journey beyond the headlines, providing a nuanced perspective that goes beyond conventional narratives. One of our most popular (and heavily restricted) collections is featured in this section, that of the Chicago Police Department’s Red Squad. This section also highlights several of CHM’s collections that reveal insights into unfair murder investigations and judicial misconduct, shedding light on the inequities within the justice system.

Example of a Red Squad record at a press conference held by the Representatives of the Businessmen for the Public Interest regarding the Red Squad at the Executive House Hotel, 71 E. Wacker Dr., Chicago, January 5, 1977. Twenty-four Chicagoans claim they were watched by the Red Squad for years and filed a lawsuit that seeks to end the police surveillance. ST-60002106-0029, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The next category features essential Published Materials and provides a curated list of books and published materials on various figures and topics. These materials offer not only in-depth insights but also serve as guideposts, pointing researchers toward other relevant sources and avenues of exploration. This section isn’t just books! There are some unique and unconventional materials here such as a scrapbook of miscellaneous Chicago crime stories, cut from 1930s-era detective magazines.

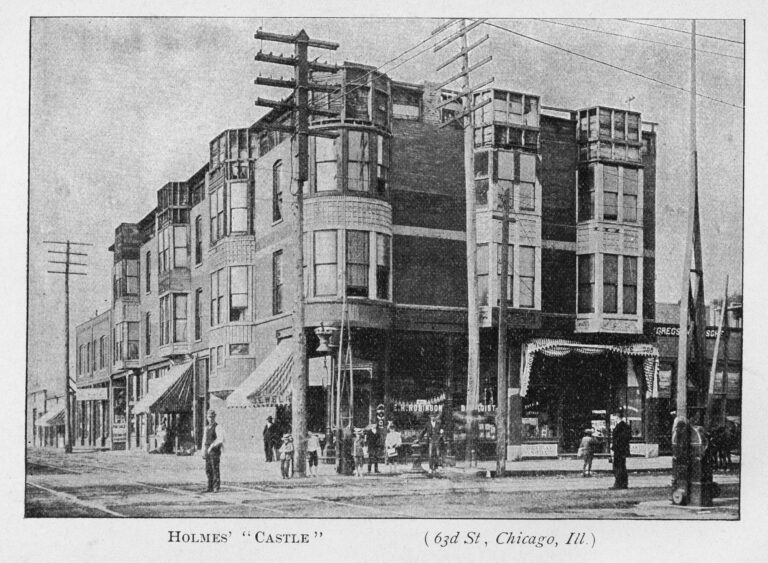

Exterior view of residence of Herman Webster Mudgett, a.k.a. H. H. Holmes, on 63rd Street, Chicago, c. 1896. Published in The Holmes-Pitezel Case: A History of the Greatest Crime of the Century. CHM, ICHi-027827

For those who prefer a strictly visual approach, the category on Image Research offers access to more than 370,000 digital images via CHM Images. Keyword searching will bring up a great deal of material relating to Chicago crime. These images, capturing crime scenes and events that defined Chicago’s past, provide a unique and evocative perspective for researchers. Delving into the Museum’s photo morgue collections, including the Chicago Sun-Times and Chicago Daily News, allows access to an additional 5 million images plus, creating a visual tapestry that recounts criminal activity in the city’s past.

Lastly, the LibGuide highlights Online and Other Local Resources, directing researchers to other institutions in the Chicago area focusing on crime and criminal justice. It is an invitation to further explore beyond CHM’s offerings.

We hope that this resource will help researchers, students, and true crime enthusiasts alike explore Chicago’s enigmatic criminal narratives.

Additional Resources

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s interviews regarding law, crime, and prison

- Purchase Karen Abbott’s Sin in the Second City: Madams, Ministers, Playboys, and the Battle for America’s Soul

Happy Halloween! CHM museum specialist Jojo Galvan explores some of the notable markers in Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery.

Close up of Eternal Silence by Lorado Taft in Graceland Cemetery, 4001 N. Clark St., Chicago, May 10, 1977. ST-40001541-0037, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

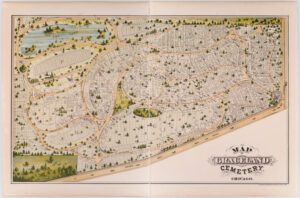

Graceland Cemetery in the Uptown community area of Chicago is many things. It’s a certified arboretum and a masterclass example of the garden cemetery movement popularized across the United States in the 19th century. But most notably to Chicagoans, the hallowed grounds are the final resting place for an extensive list of Chicago elites and eccentrics. Among its more than 2,000 trees, Graceland’s residents include the builders of the Second City, with graves for individuals like Louis Henri Sullivan, Mies van der Rohe, and perhaps most notable among them, Daniel H. Burnham, designer of the Chicago Plan and head of planning for 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. He is buried alongside his wife, Margaret, on their own private island inside the cemetery.

Burial marker for Daniel Hudson Burnham and Margaret Sherman Burnham in Graceland Cemetery, 4001 N. Clark St., Chicago, May 10, 1977. ST-40001541-0031, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Beyond architects, visitors to Graceland can also find the opulent and mysterious graves of many of the city’s elite financiers and socialites. Popular stops among the hundreds of notable graves in the cemetery include department store magnate Marshall Field, businessman Charles Wacker, and luxury sleeping car tycoon George Mortimer Pullman. Pullman is notably buried in a grave reinforced with concrete and railroad ties all under a Corinthian column and exedra, because his descendants feared his body would be disinterred and held for ransom by disgruntled employees.

Map of Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, c. 1875. CHM, ICHi-027725

One of the most imposing (and certainly the largest) and perhaps eeriest, graves in the cemetery belongs to Potter and Bertha Honoré Palmer, who made their fortune in real estate and the hospitality industry. In line with the opulence of their hotel, the Palmer House on Wabash Avenue, the Palmers are buried in two sarcophagi under an imposing Greco-Roman mausoleum, forever canonized to horror film audiences in the burial scene of Damien: Omen II, which was released in theaters in 1978.

Tomb of Bertha Honore Palmer, wife of Potter Palmer, at Graceland Cemetery, 4001 N. Clark St., Chicago, 1918. DN-0070162, Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

But beyond the graves of the well-known, the mythos of Graceland Cemetery has been elevated thanks to the folklore associated with a number of the statues adorning its gravesites, the most famous of which is undoubtedly Eternal Silence. The 10-foot-tall sculpture of a brooding, shrouded figure was designed by the renowned American sculptor and Illinois native Lorado Taft. The watchful monument guards the plot of the aptly named Graves family, descendants of Dexter Graves, one of the earliest settlers in Chicago, who arrived in the land that would come to be known as Chicago from Ohio.

Eternal Silence by Lorado Taft in Graceland Cemetery, 4001 N. Clark St., Chicago, May 10, 1977. ST-40001541-0008, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

The most widely shared story connected to Eternal Silence is a grim one. As the story goes, for those curious (and brave enough) to know how their life will come to an end, all they need to do is gaze directly at the cold, unbreaking gaze of the monument, and their fate will be revealed in a vision. Another popular monument with an eerie reputation is known as Inez Clarke. While there is some debate as to the monument’s origins and who is buried in the grave it marks, its story is a sad one. For years it’s been said that every time there’s a thunderstorm, the statue of the young girl disappears entirely from the glass vitrine covering it and returns once the skies clear because, in life, Inez was afraid of storms—a fear that carried over to other side.

Graceland, in all its mystery and beauty, is open to the public and regularly hosts tours of the grounds, both self-guided and in groups.

Additional Resources

- Visit Graceland Cemetery’s website

- Learn more about the sculptor of Eternal Silence and his other works across the city by reading the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry

- For those interested in genealogical research, the Abakanowicz Research Center (ARC) at the Museum is free and accessible to the public.

CHM curator of civic engagement and social justice Elena Gonzales writes about the history and definitions of various descriptors of people of Latin American heritage and explains why CHM is shifting from using “Latino/a/x” to using “Latine.”

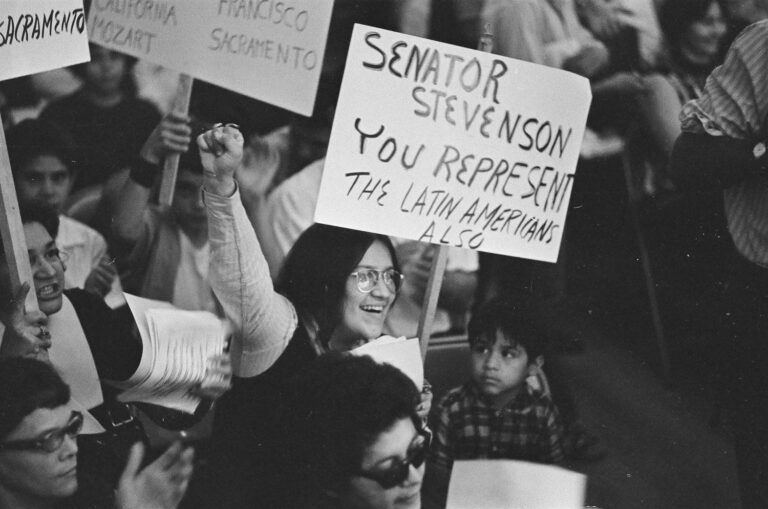

A woman holds up a sign that reads “Senator Stevenson, you represent the Latin Americans also,” Chicago, July 19, 1971. ST-60004929-0350, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Latinx, Latine, Latino, Latin@, Latin, Brown, Chicano, Hispanic. Over the years, people of Latin American heritage have described themselves in a lot of different ways, and others have described them still differently.

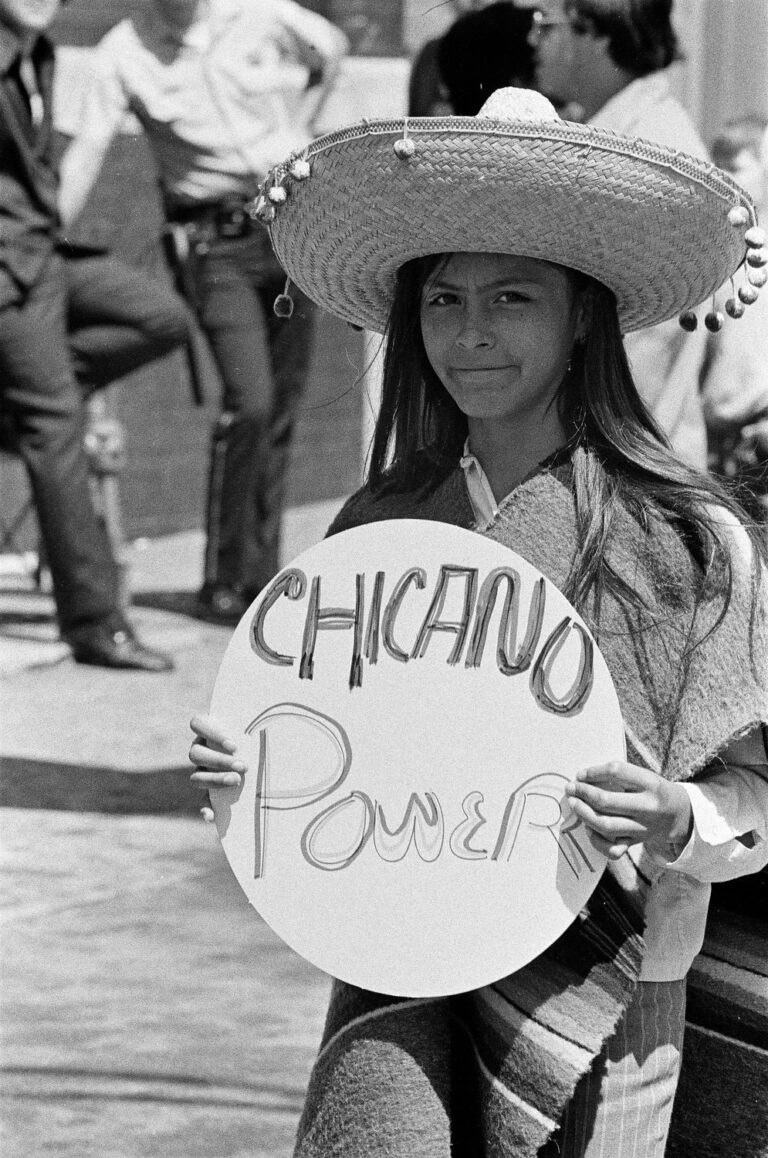

A girl holds up a sign that reads “Chicano Power,” Chicago, July 19, 1971. ST-60004929-0031, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

It can be confusing for everyone and difficult to stay up to date and feel like you’re using the “right” terminology. The fact is that there’s no definitive “right” answer but there are important considerations to make when deciding what word to use.

Most Latinos define themselves in other ways first:

- By a country (or colony) of heritage (Mexican, Puerto Rican, Guatemalteco)

- A heritage word that includes race (Afro-Brazileño, Afro-Colombiano)

- An Indigenous identity (Kichwa Otavalo)

- A local marker (Chicagoan)

That’s because all of the words like “Latino” are maddingly unspecific and they leave lots of people out, especially Indigenous folks. Just as many Latinos identify first by country of heritage, as described above, many Indigenous people identify first by Indigenous culture–outside the context of a Latin American heritage.

People holding banners during a march for Las Buenas Amigas, a Latina lesbian group in Chicago, c. 1990. CHM, ICHi-176715

We might think of Latinos as being people from Latin America, but that idea has three major problems. The first is the perception of people with Latin American heritage as perpetual foreigners when 80% of Latinos were born in the US. The second is that the very concept of “Latino” is specific to the US. Mexicans in Mexico or Ecuatorianos in Ecuador are not “Latinos.”

Thirdly, the very concept of Latin America is problematic when you really sit down and try to determine which places are “in” or “out.” There is no neat and culturally accurate solution arising from using language, geography, or colonizer as a determinant of what counts as Latin American. What about Brazilians who speak Portuguese? What about speakers of 23+ Indigenous languages in Guatemala alone? What about places such as the Philippines that are very far from the Americas but nevertheless colonized by the Spanish? What about Haiti and Belize? Things get complicated really quickly.

On a historical note, it’s important to keep in mind the context of moments in the past when we’re thinking about how to refer to folks in history. We want to try to use the terms that would best suit historical actors while still making sense today. So, while we might not use the gender-neutral terms Latine or Latinx to describe a group of men in the 1970s, we might use them to describe a group we know to include members who are more gender-fluid.

Keep in mind:

- This vocabulary is shifting even now, and the terms we like best today will continue to change. We shouldn’t be afraid to make changes in our own vocabularies as our knowledge and expression of identities change.

- Whenever you have the chance to use a specific word about someone’s heritage rather than one of these general terms, please do!

- And of course, if you’re talking about someone in particular who you know, please use the terms they prefer, just as you would for their pronouns.

A Latine Glossary for Today

Latin American: This term usually refers to someone outside the US, though, in the 1960s and 1970s it was still used to refer to folks inside the US and was often shortened to “Latin.”

Chicano/a/x: “Chicano” is a specific anticolonial political identity, not a general ethnic category. Through it, (initially young) Mexicans beginning in the 1960s have rejected the US theft of their ancestral homeland, Aztlán, and sought self-determination and solidarity with others seeking liberation.

Raza (race): “La Raza” is one identity term that acknowledges straight away that most Latinos experience race as non-white in the US. Using “La Raza” or “Raza” expresses solidarity through that.

Gente (people): “Gente” or “mi gente” is similar to “raza” in that it expresses solidarity through Spanish language.

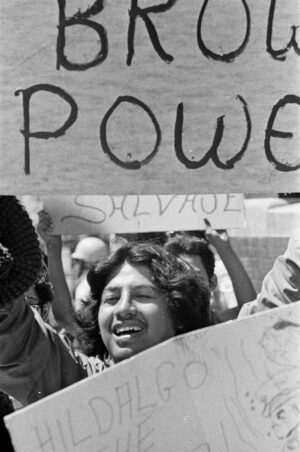

A young man holds up a sign (partially out of frame) that reads “Brown Power,” Chicago, July 19, 1971. ST-60004929-0034, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Brown: When “Hispanic / Spanish language origin” became a category on the US Census in 1980, Latino activists had been agitating for just such a change. But the word they wanted to use was “Brown.” They recognized that it carried specific meaning to identify as a racial category and that the experience of Latinos in the US was based in race. Though the Census Bureau found the addition of a racial category inconvenient, “Brown” continued to find expression in the “Brown Power” movement as well as in solidarity with other people experiencing race in America outside of whiteness. We hear the legacy of this today whenever we hear “Black and Brown people,” even though many people who are not Latino or Black also have brown skin.

Sign for Vasquez Restaurant serving “Spanish food,” along West Willow Street, Chicago, March 20, 1971. ST-10103752-0010, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

Hispanic: Without any disrespect to those who prefer to identify as Hispanic, this is the one identity term listed above that we avoid. Some people find it disrespectful because it means “of Spanish origin” and therefore places a crucial colonizer of the Americas–Spain–at the center of the identity.

Latino/a: This is the most widely embraced identity term that goes beyond country of heritage. It was added to the US Census in 2000. For a while people tried to use “Latin@” to be inclusive of gender.

Latinx: The failing of “Latino/a” is that it leaves out nonbinary folks. “Latinx” is an attempt to be more inclusive of gender nonconforming Latinos, but Spanish speakers have not widely accepted it. The criticisms are that it is difficult to say in Spanish and that people who are used to “Latino” don’t want to change their habit. In addition, despite best intentions, this term also felt like an example of linguistic colonialism–an imposition from the US.

Latine: Though “Latinx” is quite challenging to say in Spanish, “Latine” is easy. Spanish speakers are increasingly adopting this term, which originated in Spanish-speaking countries, to replace “Latinx,” and so will CHM.

Additional Resources

- Ecleen Luzmila Caraballo, “This Comic Breaks Down Latinx vs. Latine for Those Who Want to Be Gender-Inclusive.” Remezcla, October 24, 2019. Accessed October 19, 2023.

- Laura E. Gómez, Inventing Latinos: A New Story of American Racism. New York: The New Press, 2020.

- Mark Hugo Lopez, Jens Manuel Krogstad, and Jeffrey S. Passel, “Who is Hispanic?” Pew Research Center, September 5, 2023. Accessed October 19, 2023.

- G. Cristina Mora and Julia Longoria, “Latinos Are a Huge, Diverse Group. Why Are They Lumped Together?“, March 11, 2021, in The Experiment, produced by Julia Longoria and Gabrielle Berbey, podcast, 34:27.

- S. Raquel Ramos, Carmen J. Portillo, Christine Rodriguez, and Jose I. Gutierrez Jr., “Latinx: Sí, Se Puede? A Reflection on the Terms Past, Present, and Future,” Journal of Urban Health. 2023 Feb 100(1): 4–6. Accessed October 19, 2023.

October is Filipino American History Month, which commemorates the first Filipinos to arrive on the North American continent at what is now Morro Bay, California, on October 18, 1587. In October 2009, the US Congress passed a resolution officially recognizing the commemorative month.

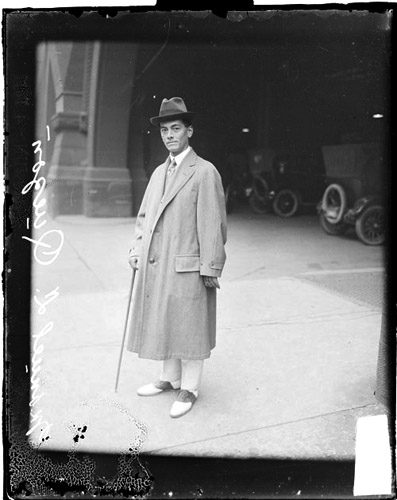

Portrait of Manuel L. Quezon, President of the Philippines, standing on the corner of a sidewalk, Chicago, 1917. DN-0067971, Chicago Daily News Collection, CHM

Before the Tydings-McDuffie Act of 1934, which led to the Philippines becoming an independent country, Filipinos immigrated to the States primarily as pensionado and family-sponsored students while the Philippine Islands was a US territory. The Pensionado Act (1903) was a program that Manuel Quezon, who later became the second president of the Philippines, passionately lobbied for in Congress and established scholarships after the Philippine-American War (1899–1902) to allow Filipinos to attend school in the States. His goal was to have a generation of young Filipinos who could become capable, democratic leaders in the Islands.

Chicago was one of the Midwest cities where ambitious, young Filipino men attended elite universities as well as to combat stereotypes from the war. They not only participated in campus life, but also in the local labor force and contributed to major movements as many settled in Chicago after immigration laws completely excluded Asians.

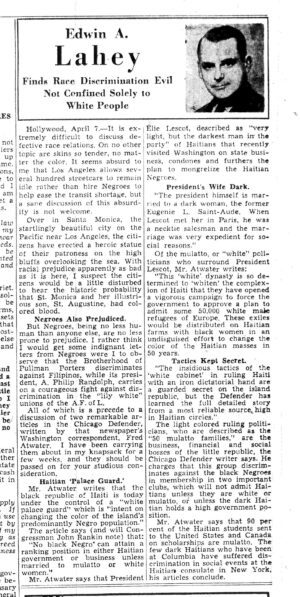

Edwin A. Lahey, “Finds Race Discrimination Evil Not Confined Solely to White People,” Chicago Daily News, p. 14, April 7, 1944.

Filipino workers also played an unintentional role in negotiations between the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) and the Pullman Company. To intimidate African American porters from joining the Brotherhood, the Pullman Company hired Filipino workers as replacements and published takedown articles to pit them against their African American coworkers. A Chicago Daily News article published April 7, 1944, insisted that the BSCP discriminated against Filipinos.

Milton P. Webster of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, 1951. CHM, ICHi-024898

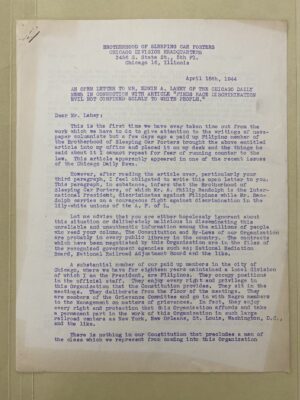

However, many of the Filipinos who came during the early pensionado years were dues paying members of the BSCP Chicago Chapter, too. Chicagoan Milton Webster, vice president of the BSCP and lead negotiator, was asked by Filipino members to respond to the Daily News article and in an open letter dated April 19, 1944, he dispelled the notion that the Brotherhood discriminated against Asian workers: “A substantial number of our paid up members in the city of Chicago, where we have for eighteen years maintained a local division of which I am the president, are Filipinos. They occupy positions in the official staff. They enjoy every right and privilege in this Organization that the Constitution provides.”

Letter from Milton P. Webster to Edwin A. Lahey, April 18, 1944. Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, box 6, folder 11. Photograph by CHM staff.

Additional Resources

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry about Filipinos

- Peruse our archival items related to the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

CHM museum specialist Jojo Galvan writes about Alfredo Cano and Bertha “Rosita” Musquiz, two professional Mexican American dancers who performed at the 1933–34 A Century of Progress International Exposition.

To celebrate Chicago’s centennial and to stimulate consumer spending in the midst of the Great Depression, the city organized the 1933–34 A Century of Progress International Exposition. That world’s fair opened on May 27, 1933, ran through November 12, 1933, and was deemed so successful that it ran again from May 26 through October 31, 1934. More than 48 million people attended the fair, which expanded across 400 acres of what is known today as Northerly Island, to marvel at the latest innovations in technology and engineering. The “Rainbow City,” as the fair came to be known, featured everything from colorful homes of the future, to the signature attraction of the fair, the Sky Ride, a mechanized transporter bridge that allowed visitors to take in the city from elevated heights.

Northerly Island during the A Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago, September 9, 1933. ICHi-031117

Beyond American innovation, visitors could see international participants showcasing culture and ingenuity from abroad. Among the slew of nations represented, one of the most popular pavilions was our neighbor south of the border, Mexico.

The entrance to Mexican Village at the A Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago, 1933. This lantern slide was hand-colored by the photographer, Anton Rodde. CHM, ICHi-176091; Anton Rodde, photographer

As one guidebook to the fair explained, those who ventured to the Mexican village could expect: “Music, dancing, and the free and easy enjoyments of the land of sunshine south of the Rio Grande . . . Señores, Caballeros, the house is yours is the attitude. Free outdoor entertainments are given by dancers and singers in fiestas in the square . . . Floor shows at 1 pm and hourly after 6 pm.”

The plaza of the Mexican Village at the A Century of Progress International Exposition, Chicago, 1933. This lantern slide was hand-colored by the photographer, Anton Rodde. CHM, ICHi-176094; Anton Rodde, photographer

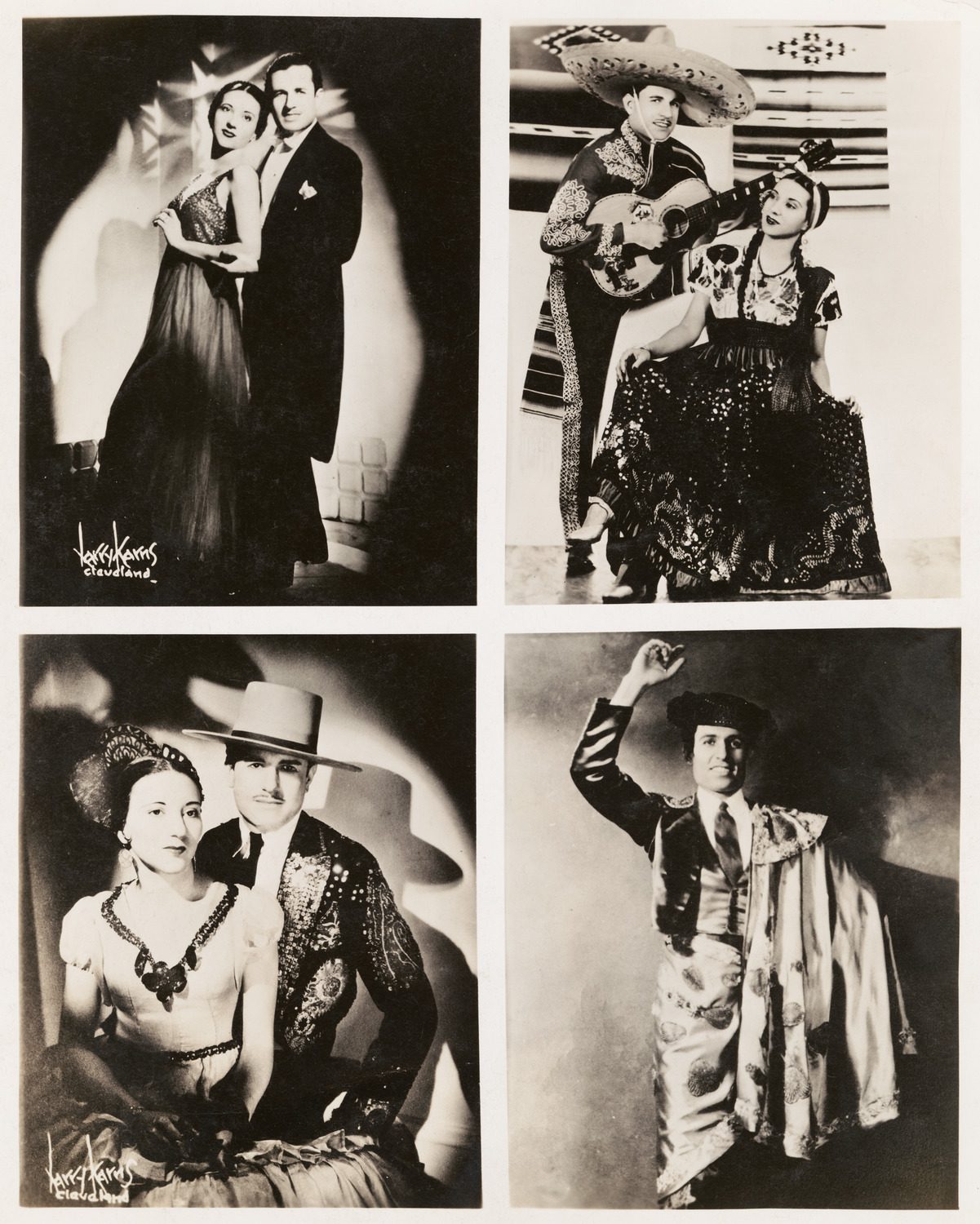

The dancers so prominently advertised as part of the Mexican Village attractions suite were two professional Mexican American dancers, husband and wife Alfredo Cano and Bertha “Rosita” Musquiz. They danced as the professional flamenco dance team known simply as “Alfredo and Rosita.” Alfredo was an immigrant from Mexico who arrived as a laborer in Chicago in the 1920s and studied dance here. Rosita was a Mexican American from San Antonio, Texas, and the two crossed paths in 1930, just at the right time to secure their positions as dancers for the Mexican Village.

Studio portrait of Alfredo Cano and Bertha “Rosita” Musquiz, c. 1930. CHM, ICHI-183252; Larry Karns Cleveland, photographer

Audience members attending Alfredo and Rosita’s show were wowed not only by the intricacy of the embroidery and brightness of the garments worn by the performers, all of which were artisan-crafted in Mexico City but also by the duo’s traditional Mexican dances, bailes folkloricos, which often tell intricate stories and legends as part of the performance.

Proof sheet of photographs of Alfredo Cano and Bertha “Rosita” Musquiz, c. 1930. CHM, ICHI-183252; Larry Karns Cleveland, photographer

Performing at the fair made Rosita and Alfredo some of the premier dancers of their day. While their performances at the world’s fair were primarily traditional Mexican dances, their general performance repertoire was robust, including other traditional Latin dances like salsa and, of course, their signature flamenco. Professionally, Alfredo and Rosita’s career spanned two decades. While they toured at performance venues, festivals, and local celebrations, bringing their rhythms to diverse crowds across the country, Chicago was always their home base, and they were staples at many of the city’s venues, like the former Cuban Village Café that once stood at 715 W. North Avenue in the Old Town neighborhood and the swanky Walnut Room at the historic Bismarck Hotel (today the Allegro Royal Sonesta Hotel) on Randolph Street in the Loop.

Front and back views of one of Alfredo’s costumes. The black wool ensemble comprises a jacket, vest, trousers, shoes (not pictured), and sombrero (not pictured). CHM, ICHi-066611 and ICHi-066610

Rosita donated a number of her and her husband’s garments to CHM’s costume collection in the 1980s, where they remain to this day. Alfredo’s elaborately crafted Charro ensemble was included in the 2003 CHM exhibition Flamenco! Latin Dance in 1930s Chicago.

Additional Resources

- Read the Encyclopedia of Chicago entry on the A Century of Progress International Exposition

- Experience what the 1933–34 world’s fair was like through our VR project, Chicago 00

In October 1848, a small group of Chicagoans witnessed the Pioneer locomotive’s inaugural run as it pulled from the city’s first railway station. CHM director of exhibitions Paul Durica writes about the winding journey it took to find its way to the Chicago History Museum.

The Pioneer locomotive endures as the historical artifact that could. Despite often being overshadowed by larger and more dynamic objects, it has managed to appear (with some modifications to its appearance over the years) at every significant Chicago fair and festival from the 1880s through the 1940s, including both the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and the 1933–34 A Century of Progress International Exposition, before finding its forever home at the Chicago History Museum.

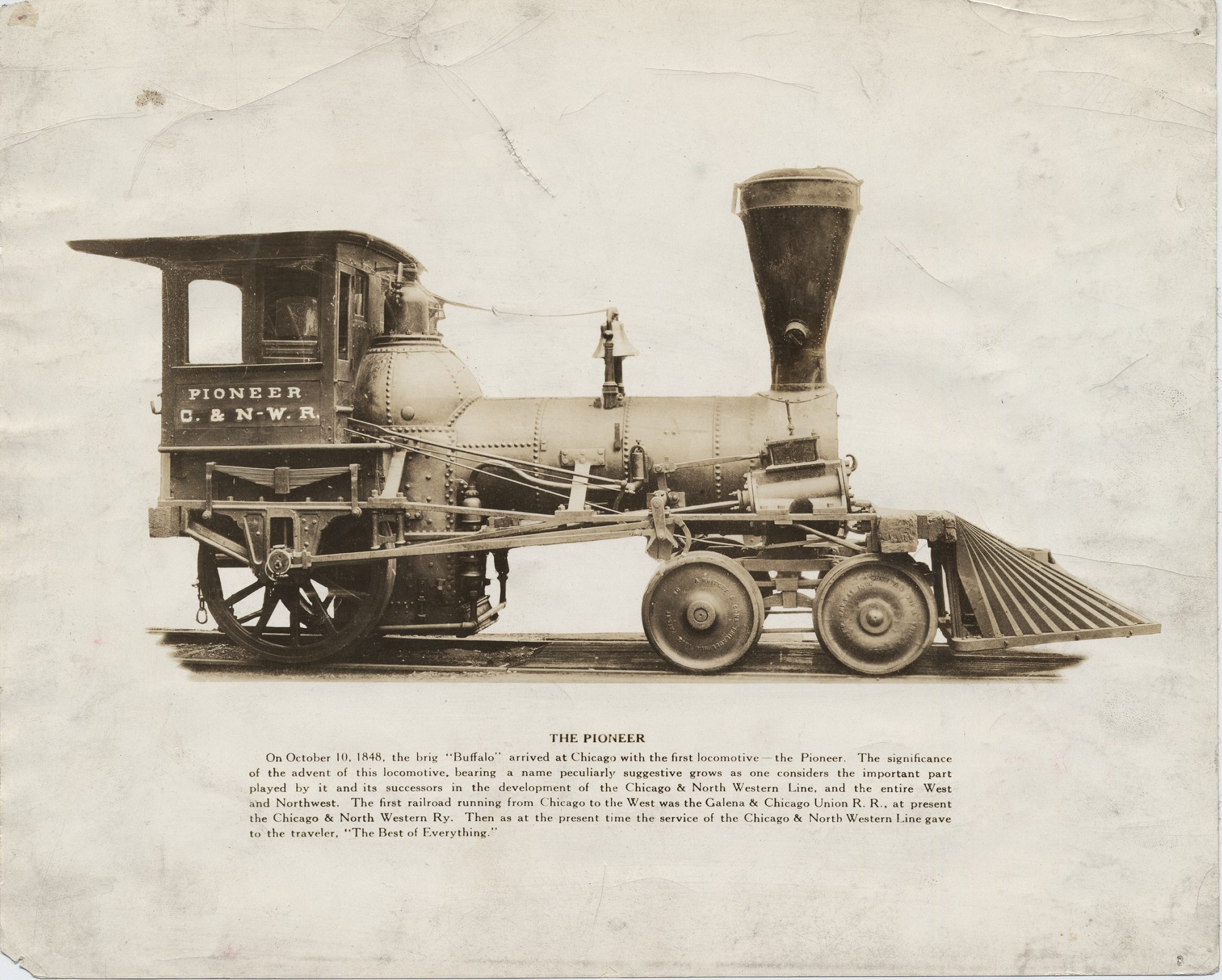

An undated photograph of the Pioneer. The first sentence of the caption reads: “On October 10, 1848, the brig ‘Buffalo’ arrived at Chicago with the first locomotive—the Pioneer.” CHM, ICHi-037010

As the first locomotive to operate within the city, the Pioneer has long remained, in the words of one commentator, the “historic symbol of the coming of the railroads” to Chicago and the nation, transforming both in challenging and enduring ways. A small group of Chicagoans witnessed the Pioneer on its inaugural run as it pulled from the city’s first railway station, near the intersection of present-day Canal and Kinzie Streets, 175 years ago this October. Whether they regarded what they witnessed with optimism, skepticism, or some mix of the two was not recorded.

That first ride on the rails of the still-under-construction Galena and Chicago Union Railroad stretched as far as Des Plaines, Illinois, transporting a group of prominent citizens one way and the same group along with some grain, back to Chicago. Bought second-hand (though with no bill of sale, the origin of the Pioneer remains unknown; it was likely manufactured c. 1840 for an eastern railroad company), the Pioneer was replaced within a decade by bigger, faster, more powerful locomotives as first the Galena and Chicago Union and then other railroad lines expanded throughout the 1850s. As the Chicago Tribune described that first run a century later, this “little event in October 1848. . . was the forerunner of a mighty development that ultimately made Chicago the greatest railroad center in the world.”

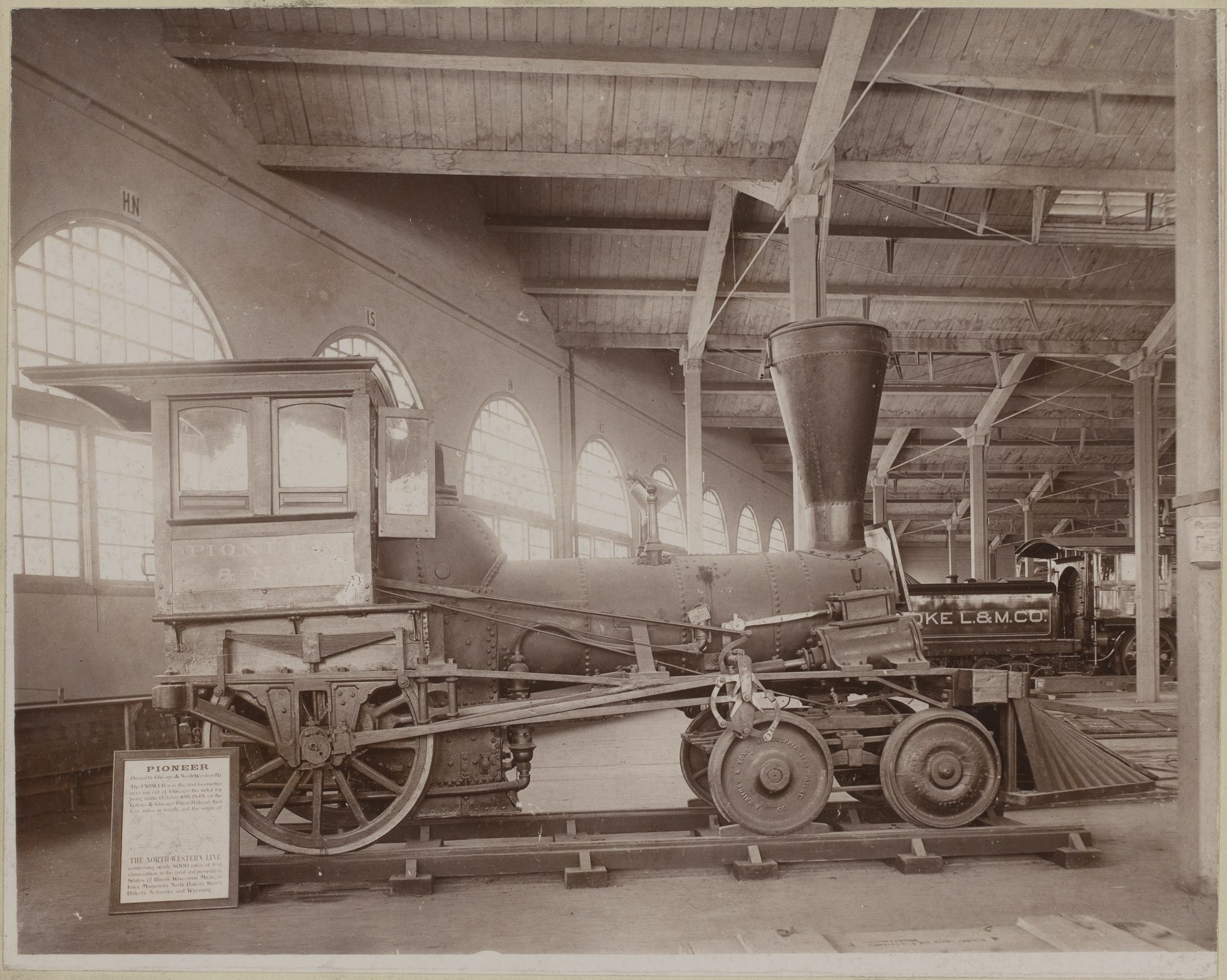

In 1883 Chicago celebrated being the “center” of the railroad industry by hosting the National Exposition of Railway Appliances. One of the featured exhibits was the Pioneer, which had from about 1858 to 1874 been used solely for company and construction work and was now deteriorating in a train yard. Given a fresh coat of paint, its significance supported by the memories of retired engineers, the Pioneer had pride of place at the Exposition, but this was a prelude to the exposure it soon received at one of the most significant events in Chicago history.

The Pioneer on display in the Transportation Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-050434

This year marks the 130th anniversary of the World’s Columbian Exposition, the first Chicago world’s fair, an event invested in celebrating the past even as it looked toward the coming twentieth century. At the fair, in the Transportation Building designed by Louis Sullivan, the only one among the fourteen main structures not inspired by the classical past, stood that relic of Chicago, the Pioneer, “a funny-looking contrivance as compared with the great locomotives now in use,” according to the Tribune. There to tell its story was John Ebbert, who claimed to be its first engineer as well as an eyewitness to its arrival via the Great Lakes on the brig Buffalo. Ebbert’s stories of the early days of rail entertained visitors from around the world and established the Pioneer as an important symbol of this history. Today a variation of this experience at the World’s Columbian Exposition survives in an interactive display in the Museum’s Chicago: Crossroads of America exhibition.

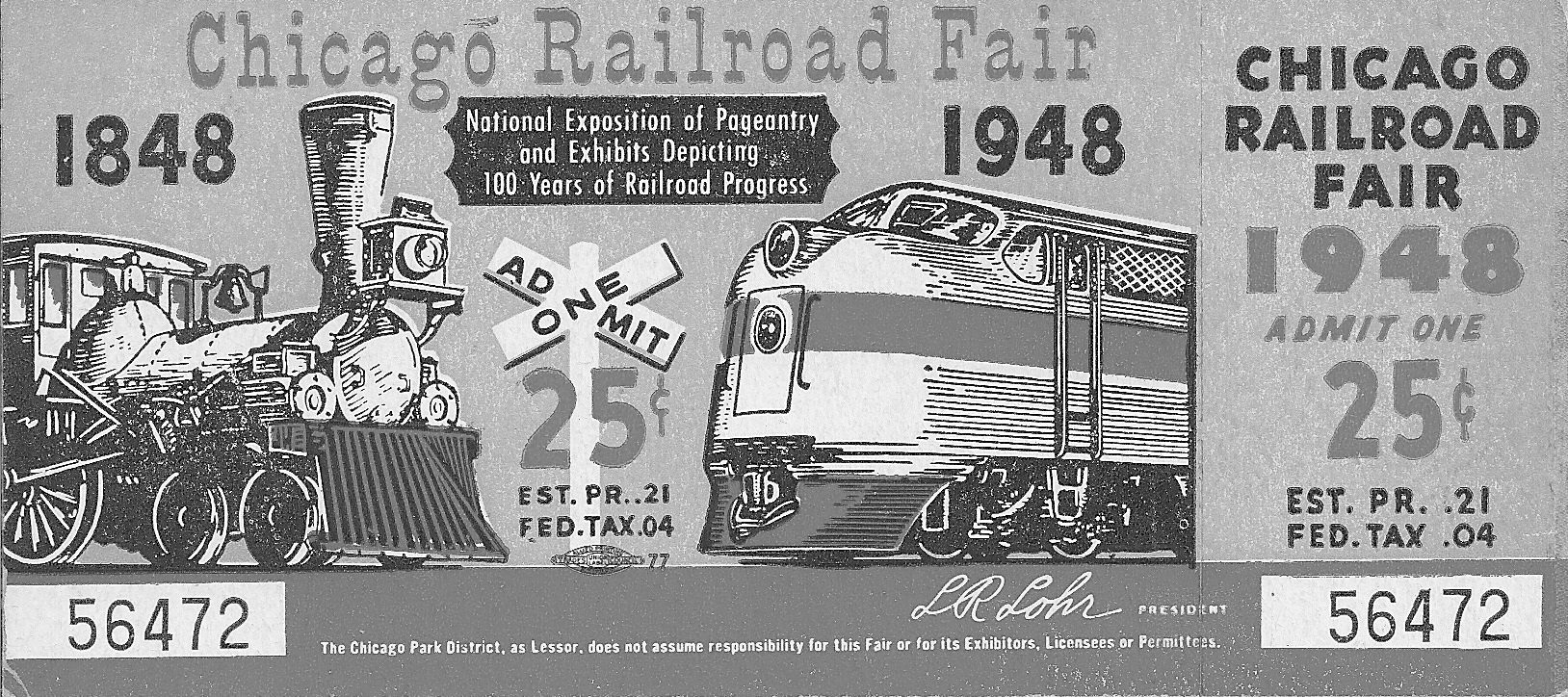

An admission ticket to the 1948 Chicago Railroad Fair. According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics inflation calculator, 25¢ in 1948 is equivalent to $3.15 in 2023. Courtesy of Joseph M. Di Cola.

From the World’s Columbian Exposition, the Pioneer embarked on a long, winding journey that would take it, among other places, to the Columbian Museum (today’s Field Museum), the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, A Century of Progress world’s fair, the Museum of Science and Industry, and the 1948 Chicago Railroad Fair.

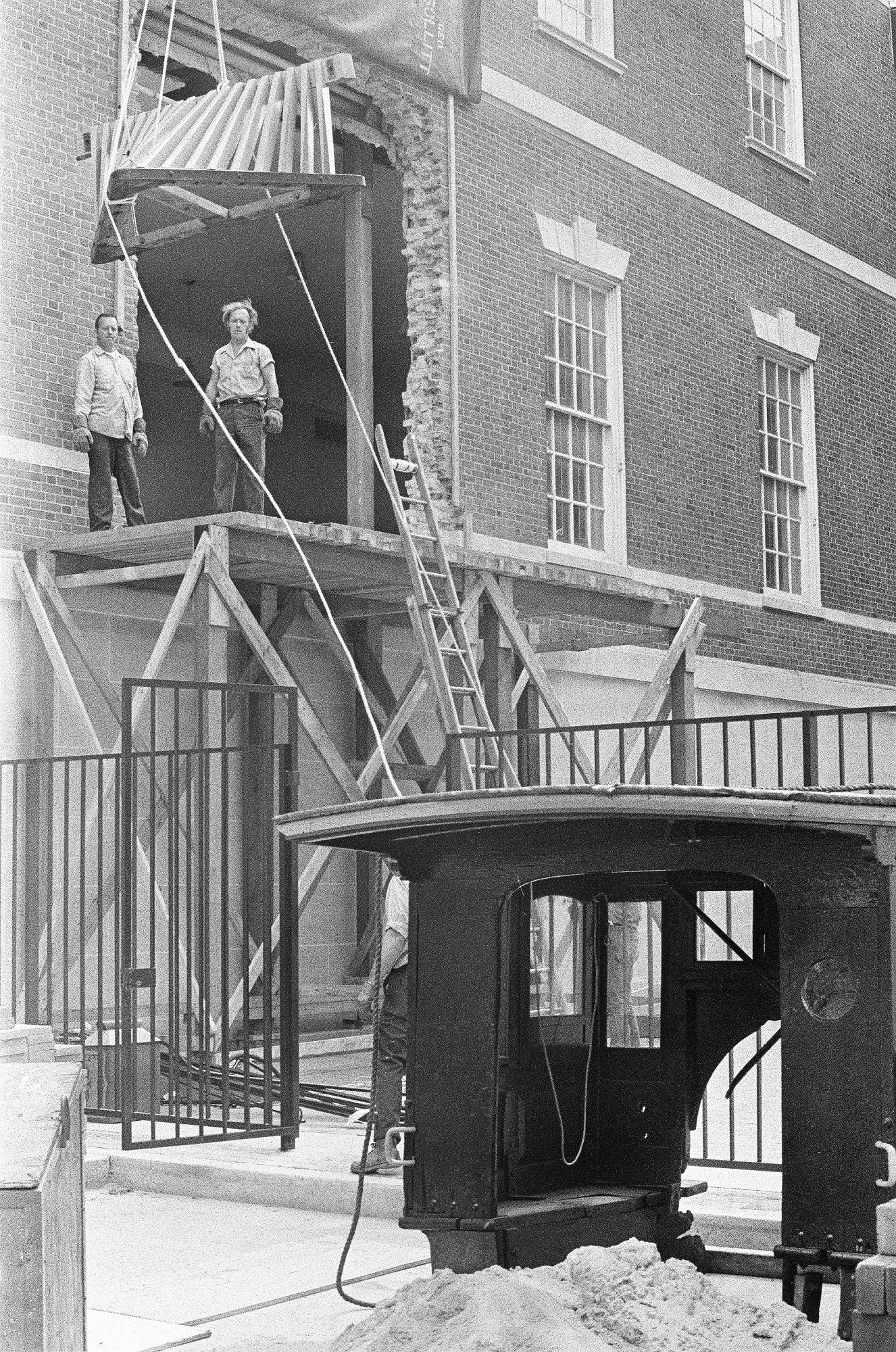

The cowcatcher of the Pioneer being lifted into the Chicago Historical Society (Chicago History Museum), August 15, 1972. ST-19031875-0010, Chicago Sun-Times collection, CHM

It wouldn’t arrive at the Chicago Historical Society until 1972 and would, along with the 1892 L Car, become one of two large artifacts in Chicago: Crossroads of America when it opened in 2006.

The Pioneer on display in Chicago: Crossroads of America.

There’s one small problem with this whole long story: the Pioneer visitors know may not have pioneered anything. The Pioneer isn’t named in any documents until 1856, when it appears in a Galena and Chicago Union inventory, and there were other locomotives in the company’s stock that fit the description of the one that first left the station in October 1848 (the exact date of which is somewhat disputed by historians). The Pioneer’s history rests solely upon the reminisces of old railroad workers, first taken down in the 1880s and 1890s. “A bill of sale, a contemporary newspaper story, an old diary entry, any scrap dating back to October 1848 might settle the question,” writes John H. White in his survey of the documentary evidence surrounding the Pioneer from 1976. “Perhaps some industrious scholar will one day find the missing information.”

But perhaps having witnessed so much of the city’s history in the last 175 years, where this humble locomotive began its journey and whether it was the first really doesn’t matter anymore?

Sources

- “All Are of Interest: Exhibits to Be Seen in the Transportation Building,” Chicago Daily Tribune, April 30, 1893.

- Paul Angle, “Chicago’s First Railroad,” Chicago History, vol. 1, no. 12 (Summer 1948).

- Philip Hampson, “Chicago Railroad Fair Opens Today,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 20, 1948.

- Patrick McLear, “The Galena and Chicago Union Railroad: A Symbol of Chicago’s Economic Maturity,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, vol. 73, no. 1 (Spring 1980).

- John H. White Jr., The Pioneer: Chicago’s First Locomotive (Chicago: Chicago Historical Society, 1976).

Chicago has undoubtedly become one of the culinary epicenters of the world. The city’s location in the middle of the country and its diverse communities make it easy to find memorable bites in every neighborhood. The city’s culinary prowess took root at the end of the nineteenth century when Chicago was at the forefront of the nation’s agricultural revolution as both the “Hog Butcher for the World” and a major transportation hub.

The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE) opened Chicago’s doors to millions and allowed the US to show off what it had to offer. While replete with memorable architecture and technological innovations, the many culinary offerings throughout the White City and the Midway Plaisance enticed and enchanted the palates of all those who came through the fair. We can thank the WCE for introducing some of the most well-known foodstuffs enjoyed by generations of consumers worldwide. This list is by no means exhaustive. We welcome you to share your favorite culinary legacies from the WCE in the comments!

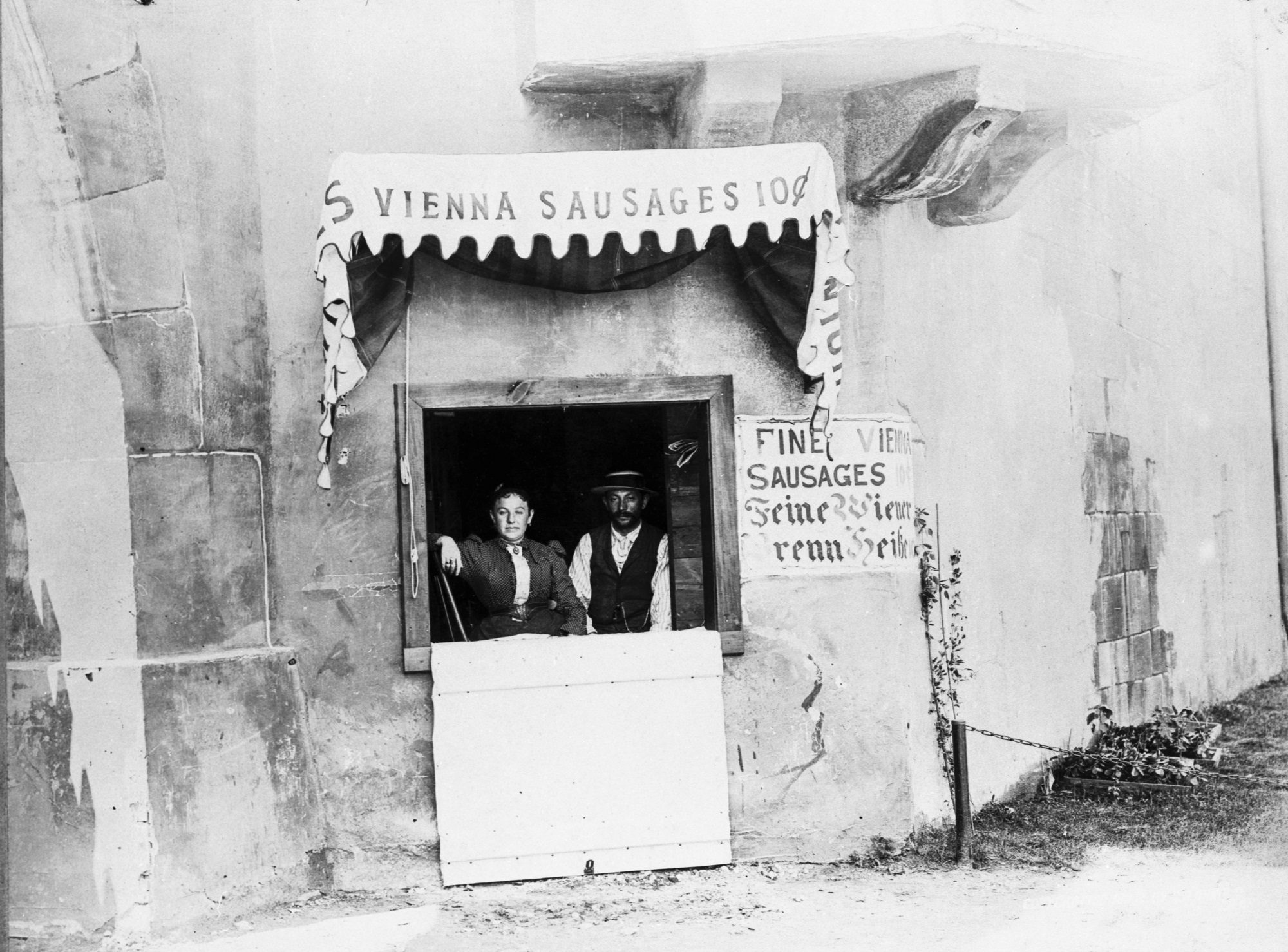

Vienna Beef

Vienna Sausage Place in the Austrian Village at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-002453; C. D. Arnold, photographer

Vienna Beef Inc. is arguably the hot dog king of Chicago. Vienna’s reign began at the 1893 fair with two entrepreneurial brothers-in-law, Emil Reichel and Samuel Ladany. The pair of entrepreneurs set up shop in “Old Vienna,” an exhibit that was part of the Midway Plaisance, where they charged a dime for their sausages topped with onions and mustard. Popular due to their distinct flavor, accessible price, and heartiness, Reichel and Ladany stayed in the city and set up shop on Halsted Street, opening a store and factory that became the Chicago legend known the world over today. The most important rule of all—no ketchup.

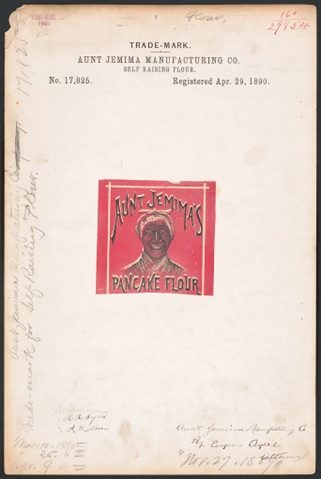

Aunt Jemima Pancake Mix

Trademark registration by Aunt Jemima Manufacturing Co. for Aunt Jemima’s Pancake Flour brand Self Raising Flour, LC-DIG-trmk-1t17825, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

While all products branded with Aunt Jemima were renamed to Pearl Milling Co. in June 2021, the boxed pancake mix found in nearly every grocery store in America is one of the more complicated food legacies from the WCE. Aunt Jemima was a formerly enslaved woman from Kentucky named Nancy Green, who was hired to do cooking demonstrations to promote the cake mix. Her demonstrations typically included songs and other performances widely associated with racist mammy caricatures. At the fair in Chicago, thousands saw Green perform, bringing national attention to the product she promoted. Green passed in August 1923 as part of a car crash. She was buried in Oak Woods Cemetery on the city’s South Side. Her grave was unmarked until 2015, when after a decade of research, Green’s remains were finally verified, and a marker for her was installed.

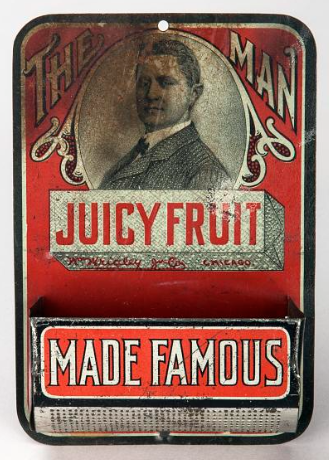

Juicy Fruit Gum

Wm. Wrigley Jr. Company Juicy Fruit gum tin, c. 1893. The tin was designed to hang against a wall or other flat surface, and the gum would be held in the basket on the bottom front of the tin. National Museum of American History, AG.293320.2740.

When William Wrigley Jr. moved from Philadelphia to Chicago in 1891, he was in the soap business. To incentivize purchases, he was known for giving away freebies to those who purchased his products, primarily baking soda and his own brand and flavors of chewing gum. When the WCE opened, he gambled on a new flavor to entice potential customers, an artificially-flavored sweet strip simply named “Juicy Fruit.” As fate would have it, the gum would come to be far more popular than the rest of the products Wrigley was selling, turning him into Chicago’s very own candy magnate. His fortunes would be so significant that he left his footprint on the city’s built environment with the Wrigley Building downtown and, later, through his acquisition of Wrigley Field, home of the Chicago Cubs.

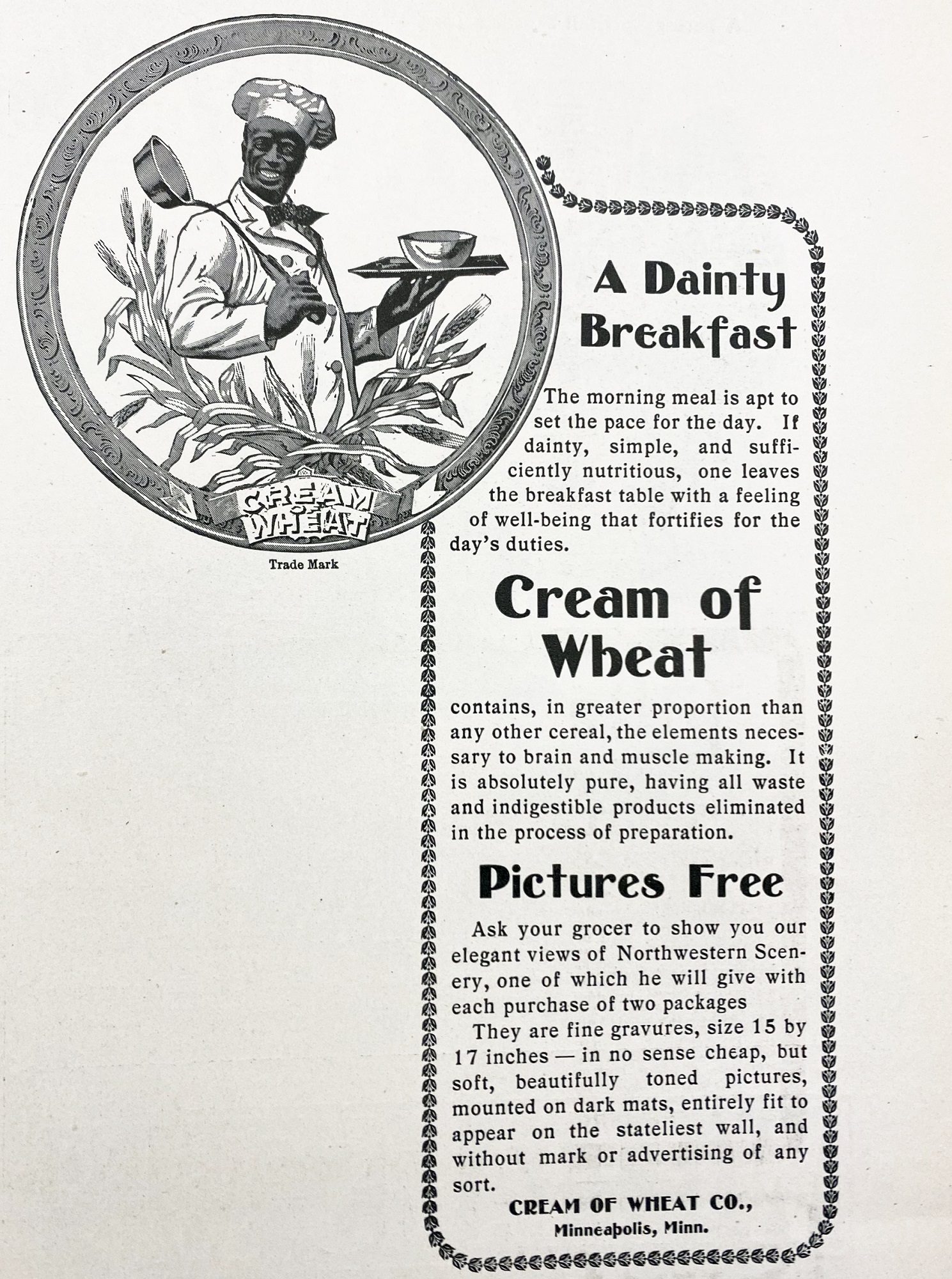

Cream of Wheat

Cream of Wheat advertisement in Harper’s Bazaar, November 18, 1889.

Cream of Wheat, known to many as a breakfast porridge, also debuted at the WCE. While its taste wasn’t the most popular product amongst the culinary critics of the fair, it gained popularity because of how quickly it could be prepared as well as its heartiness. Presented by the Grand Forks Diamond Milling Company out of North Dakota, their straightforward approach was to grind down wheat and make it into farina cereal. After the fanfare in 1893, the proprietors of the mill marketed their creation across women’s magazines and newspapers, which led to national consumption and an eventual listing on the New York Stock Exchange.

Hershey’s Chocolate

While Hershey’s Chocolate didn’t launch at the 1893 world’s fair, the fair was nonetheless integral in the story of America’s most well-known chocolate bar. Before he was a chocolatier, Milton S. Hershey was already a candy entrepreneur, staking his fortunes on selling caramel treats. Like countless other entrepreneurs and curious onlookers, Hershey attended the WCE to catch a glimpse at the future of commerce and manufacturing, and it would be here that his business outlook changed dramatically. After witnessing a demonstration of German chocolate-making equipment, he placed an order and had the equipment shipped back to Pennsylvania and incorporated the Hershey Chocolate Company in 1894.

Finally, for those of you looking to bring the taste of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition to your kitchen table, there exists a souvenir cookbook with more than 2,000 recipes “contributed by over two-hundred world’s fair lady managers, wives, of governors, and other ladies of position and influence.” The entire text has been digitized and can be accessed for free via HathiTrust.

Additional Resources

- To experience what a day at the fair would be like through virtual reality, visit the Chicago00 Project’s tour of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition

- Get a glimpse into the past with our historical menu collection through Touring Chicago’s Culinary History, a Google Arts & Culture story

CHM research and insights analyst Marissa Croft writes about the gap in experience between high society dress and visitors to the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition who traveled in from all over the world to attend.

If you’re taking a trip to an unfamiliar place, one of the first questions you might ask yourself is “What should I wear?” In 1893, millions of people departing for the World’s Columbian Exposition (WCE) in Chicago asked themselves the same question. The month before the exposition opened, Lida Rose McCabe, a reporter for the Los Angeles Times wrote: “Everybody is going to the World’s Fair . . . We all desire to look our best there, and to be at our best.”

Women’s fashion magazines leapt at the chance to offer advice to their readers on how to look their best, because “The majority of women who contemplate going to the Chicago Exposition are inexperienced travelers . . . the journey in many instances will be the first, the greatest ‘outing’ of their lives. Naturally they want to make a good appearance and get the most out of the occasion.” (McCabe, Los Angeles Times). Selecting outfits carefully was critical, as travelers were limited in the amount of luggage that they could bring on the train for their multiple week long stays: one medium hard-sided “telescope” case and a large clasp top handbag or “alligator bag.” These fashion magazines encouraged female travelers to pack a minimal toilet, lightweight, comfortable garments, and noted that “two or three dresses with extra shirtwaists will be sufficient to carry for the stay of a few weeks at the fair.” (Fessenden, “The Trip to Chicago,” Harper’s Bazaar) Furthermore, it was advised that money might be saved on laundry by bringing only dark colored stockings and petticoats, and underclothes that could be washed in the sink. A women could also save space by wearing her heaviest garment during the journey. Depending on the month, this travelling gown might be made of storm serge for rain, silk for the heat, or wool for the cold. A cape made of broadcloth would complete the look.

Here are some women at the WCE who took Harper’s practical fashion advice. CHM, ICHi-170162

Men’s attire at the WCE did not differ significantly from their normal day-to-day dress, although it provided a strong contrast with the wide array of garb worn by the exhibitors in the international pavilions. In the photograph below, two men in loose-fitting robes and astrakhan caps speak to a group of visitors attired in bowler hats and tailored jackets.

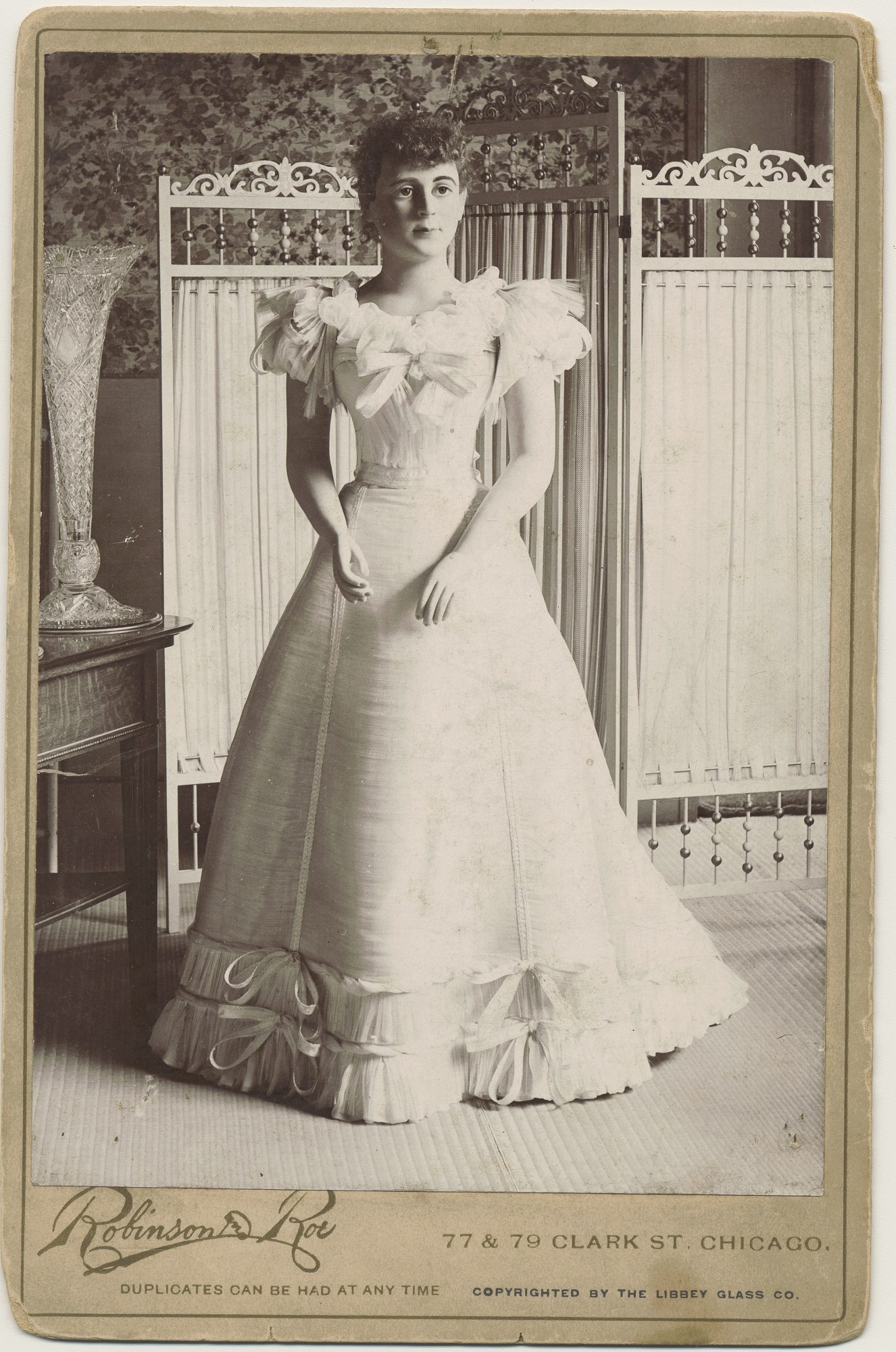

Clothing was also a central educational fixture of the WCE. There were panel sessions held by the National Council of Women about how women’s dress could be improved. The Women’s Tribune reported the following dress code issued for panel attendees: “the clothing from head to foot, shall be entirely free from stiffness and constricting bonds, and that it shall be suitable to the occasion for which it is intended.” At the Midway Plaisance, near the entrance was an entire building dedicated to global attire called the International Dress and Costume Exhibit, which contained 40 different examples of women’s dress from 40 different countries. New novelties in clothing technology were on view across the fair, from displays of Japanese textiles and Venetian lace to the Libbey Glass Company’s gown made entirely from fiberglass.

The Famous Glass Dress from Libbey Glass Company’s Crystal Palace in Midway Plaisance, World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893. CHM, ICHi-061750; Robinson & Roe, photographer

Although most attendees were only able to look at these fine fashions, there were an elite few who actually wore them: the dignitaries and socialites present at the fair. Many of these individual gowns now reside in CHM’s collection. This evening dress worn by Mrs. John (Annie D. Larrabee) DeKoven to the WCE’s inaugural ball is made of pink brocade with collar and front skirt panel of white silk and net embroidered in pearls and silver thread. It would certainly not be an easy garment to pack for train travel and stands in stark contrast to the plain and practical attire worn by the millions of attendees who flocked to take in the sights.

Evening dress of pink brocade with white lace jabot and cuffs, c. 1892. CHM, ICHi-066213

As you might have noticed, the historical record of what outfits the average person wore to the 1893 world’s fair comes primarily from candid photographs and printed articles, while examples of elite dress come from posed photographs and extant garments. Although we can certainly learn much about fashion from printed sources, such as those housed in the Abakanowicz Research Center, this gap points to a collecting divide that privileged elite garments connected to the WCE over those worn by attendees with less means. This raises an important question: When museums collect clothing, should they collect representative examples of what was most worn at the time or focus on preserving the most extravagant and artistic clothes? More broadly speaking, is it a museum’s job to share the stories of the many or of a minority of elite?

Additional Resources

- Browse CHM’s images of extant garments from around the time of the 1893 world’s fair

- Visit the Abakanowicz Research Center (ARC) to view primary sources from the 1893 world’s fair to learn more about what the average person wore, such as: Harper’s Bazaar (1867–1986), a useful source for fashion illustrations, in-depth descriptions of dressmaking techniques, and patterns for everything from embroidery designs to actual clothing. Various issues from 1867 through 1900 are accessible in the ARC. Advance notice is required to view issues printed after April 28, 1900; Pocket guide to the latest fashions from the Hub for Spring & Summer, 1893; Putnam House Catalogue, Spring and Summer 1893.

Works Cited

- “World’s Fair Notes: Dress Reform Day.” The Woman’s Tribune 10, no. 19 (April 22, 1893): 76.

- Fessenden, Laura Dayton, “The Trip to Chicago.” Harper’s Bazaar, May 13, 1893, 378–79.

- McCabe, Lida Rose. “In The Style.”: What Women May Wear at The World’s Fair. A Woman’s Outfit for A Fortnight’s Stay–How Travel in Comfort and How to Dress Becomingly.” Los Angeles Times (1886–1922), April 2, 1893.

To mark Labor Day 2023, CHM editor Heidi Samuelson writes about Polish-born John Kikulski, a Chicago labor leader in the early twentieth century. You can see more about Kikulski in our exhibition Back Home: Polish Chicago.

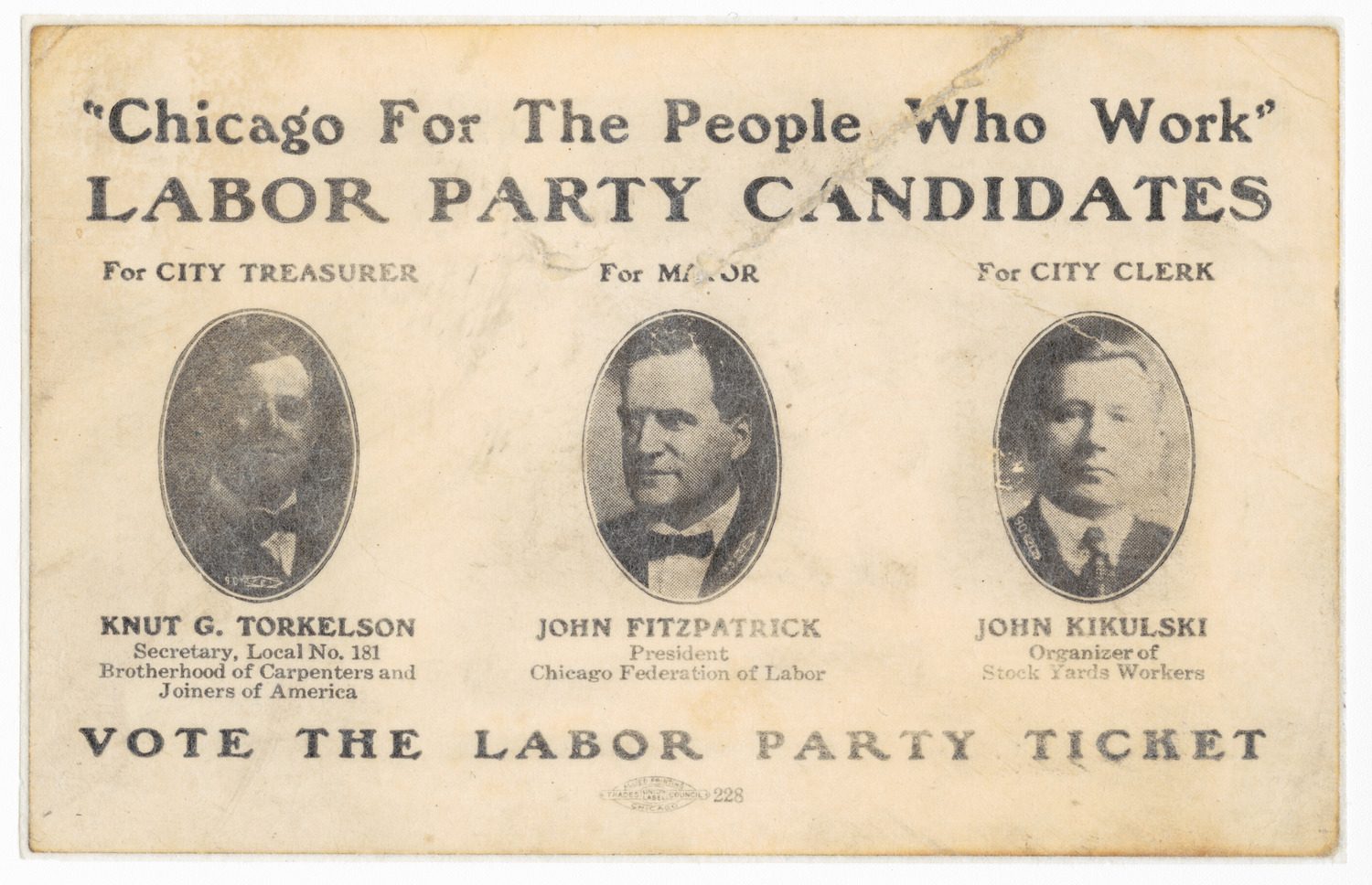

Labor Party candidates palm card, Chicago, 1919; CHM, ICHi-182716-001

John Kikulski was born in the village of Okinin in German-occupied Poland in 1876 to Ludwig and Catherine (Graf) Kikulski. He received his elementary education in Poland, and likely immigrated to the United States around 1889. Upon arriving in Chicago, he attended night schools to learn English and found an apprenticeship as a wood maker. He became a US citizen, and in 1898 he married Mary Wajert of Chicago. The couple had two children.

Kikulski was active in Chicago’s labor movement from the late 1890s on. He became a labor official of the Wood Workers’ Union in 1901 and was later elected president of Local 14 after the union became amalgamated with the Mills and Factory Carpenters’ District Council.

Also active in Polish community organizations, Kikulski was a member of St. Hyacinth’s Parish and the Polish National Alliance, for which he served as director for one term in 1904. He also served as president of the Polish Falcons (now Polish Falcons of America) from 1910 to 1912. Kikulski’s first attempt to enter city politics came in 1903 when he ran for Sixteenth Ward alderman on the Independent Labor Party ticket and lost.

During World War I, Kikulski worked as an organizer for the American Federation of Labor (now the AFL-CIO) and helped to lead strikes at International Harvester and the Crane Company. In 1917, he joined the stockyards labor movement where he gained his greatest success. Packinghouse workers elected him president of the largely Polish Local 554 of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen and later secretary of the Stockyard Labor Council. The Stockyard Labor Council worked to unite Black and white laborers, men and women laborers, and laborers of various skill levels. They had the support of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters union and the Chicago Federation of Labor, and with the intervention of federal mediators gave workers higher wages and an eight-hour workday.

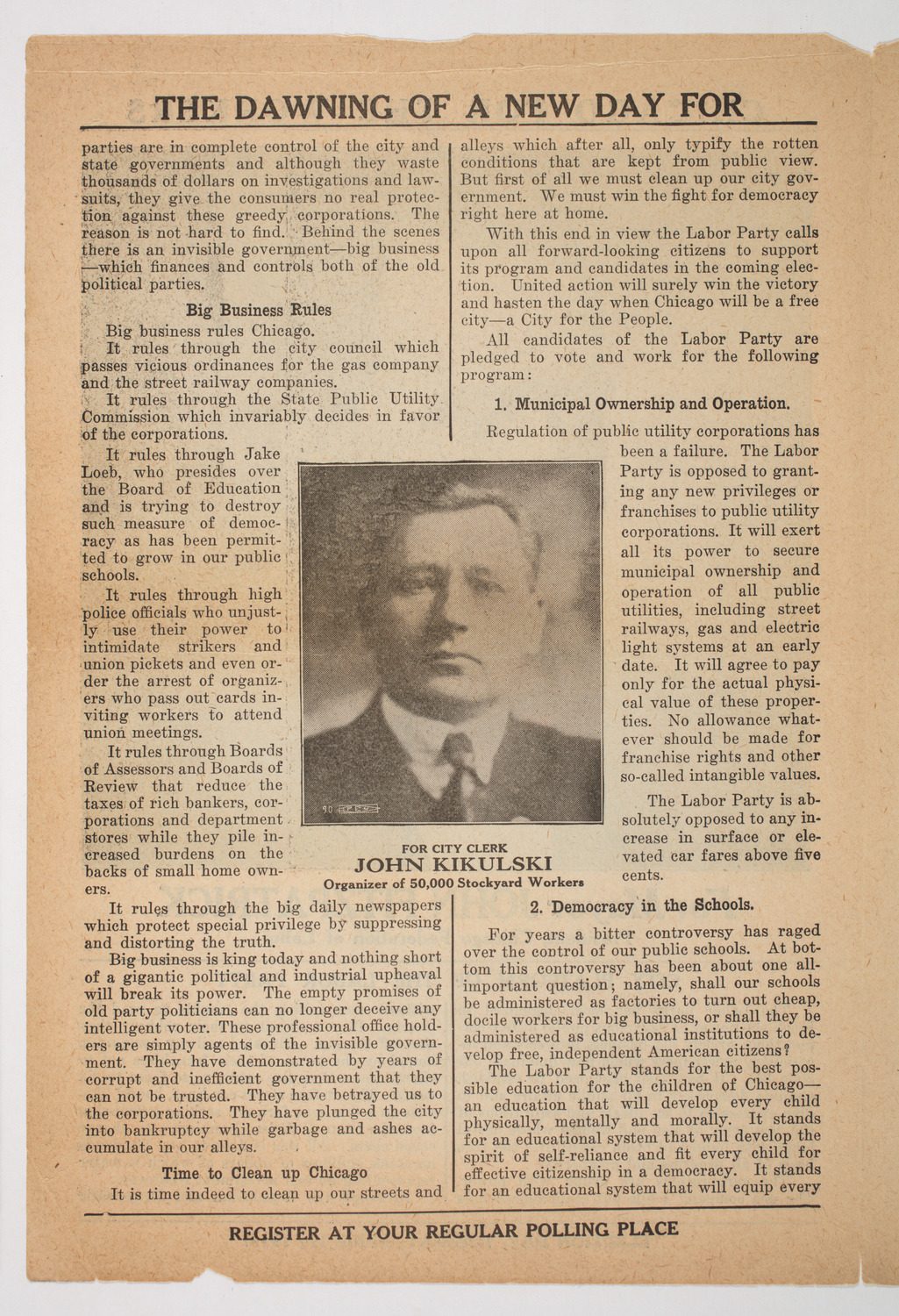

Second page of a political flyer for the Labor Party, which includes a portrait of John Kikulski for city clerk, in advance of election day on April 1, 1919, Chicago. CHM, ICHi-182719-002

Following the union’s success, members voted Kikulski director of District 9 of the meat cutters’ union. In 1919, he ran an unsuccessful campaign for city clerk as the Farmer-Labor Party candidate. As a candidate, Kikulski preached racial harmony and working-class unity, but the momentum gained in the stockyard movement was damaged by the race riots of 1919. The Chicago Federation of Labor issued a statement on August 9 accusing the packing houses of exacerbating the riots in a further attempt to polarize Black and white workers as well as denying Kikulski, J. W. Johnstone, and Martin Murphy of the Stockyards Labor Council entry to a meeting with superintendents of all the packing plants and police.

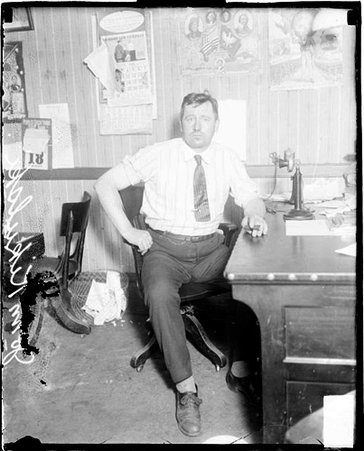

Informal portrait of John Kikulski in an office in Chicago, 1919. DN-0071292, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

Later that year, Kikulski defected from the Council and continued to be entangled in Chicago’s labor wars. Various factions accused him of embezzling money, though his working-class supporters remained loyal. However, on May 17, 1920, two unknown assailants attacked and shot Kikulski in front of his home. He died four days later. Kikulski received a hero’s burial as mourners filled St. Hyacinth’s Basilica beyond capacity. A procession of some two hundred automobiles escorted his casket to St. Adalbert’s Catholic Cemetery.

Additional Resources

- “John Kikulski and Chicago Labor” in the Encyclopedia of Chicago

- Back Home: Polish Chicago exhibition

- The Red Summer of 1919 blog post

After nearly three decades with the Chicago History Museum, CHM reference librarian Lesley Martin is retiring this October. In this special staff spotlight, she reflects on her time as an editor and librarian at CHM.

CHM reference librarian Lesley Martin (right) with patrons in the Abakanowicz Research Center, 2015. All photographs by CHM staff.

How did your career path lead you to the Chicago History Museum?

I came to CHM as a librarian who had left public libraries and was freelancing as a researcher, fact-checker, and indexer. I did several projects in the former Publications Department. (Most unusual assignment—labels for a show on Jockey underwear! [Ed. note: A Brief History: The Jockey Underwear Story, October 2, 1993–January 15, 1994]) In 1995, I was hired as one of the full-time editors. Along with editorial colleagues, I edited exhibition labels and Chicago History magazine articles, proofread invitations, produced CHM’s events calendar, annual reports, etc. It was a great job, but after about five years, a position opened in the Research Center (Ed. Note: Now the Abakanowicz Research Center [ARC]), and I was unable to resist the chance to work directly with the research collections. I had used the 2D collections to do fact-checking and photo research as an editor, but as a reference librarian, I could walk right into the storage areas and explore more fully. Assisting researchers has given me many opportunities to dig into the Museum’s collections.

What’s your favorite part about your job?

The ARC gives individuals the chance to explore their own particular interests in CHM’s collections, and my favorite part of the job is connecting them with what they need. Some researchers may be attempting to verify a family legend; graduate students come looking for materials to support a dissertation topic; moviemakers and set designers want photographs with visual details for a particular era; novelists seek out the circumstances of everyday life in a different time; architects check our collections for blueprints of a commercial building that’s being restored or perhaps converted to condominiums; guides hunt for telling details to include in tours of the city. (This year, the Education Department’s partnership with My Block, My Hood, My City brought in youth guides working on tours of their home neighborhood, North Lawndale.) It’s never dull!

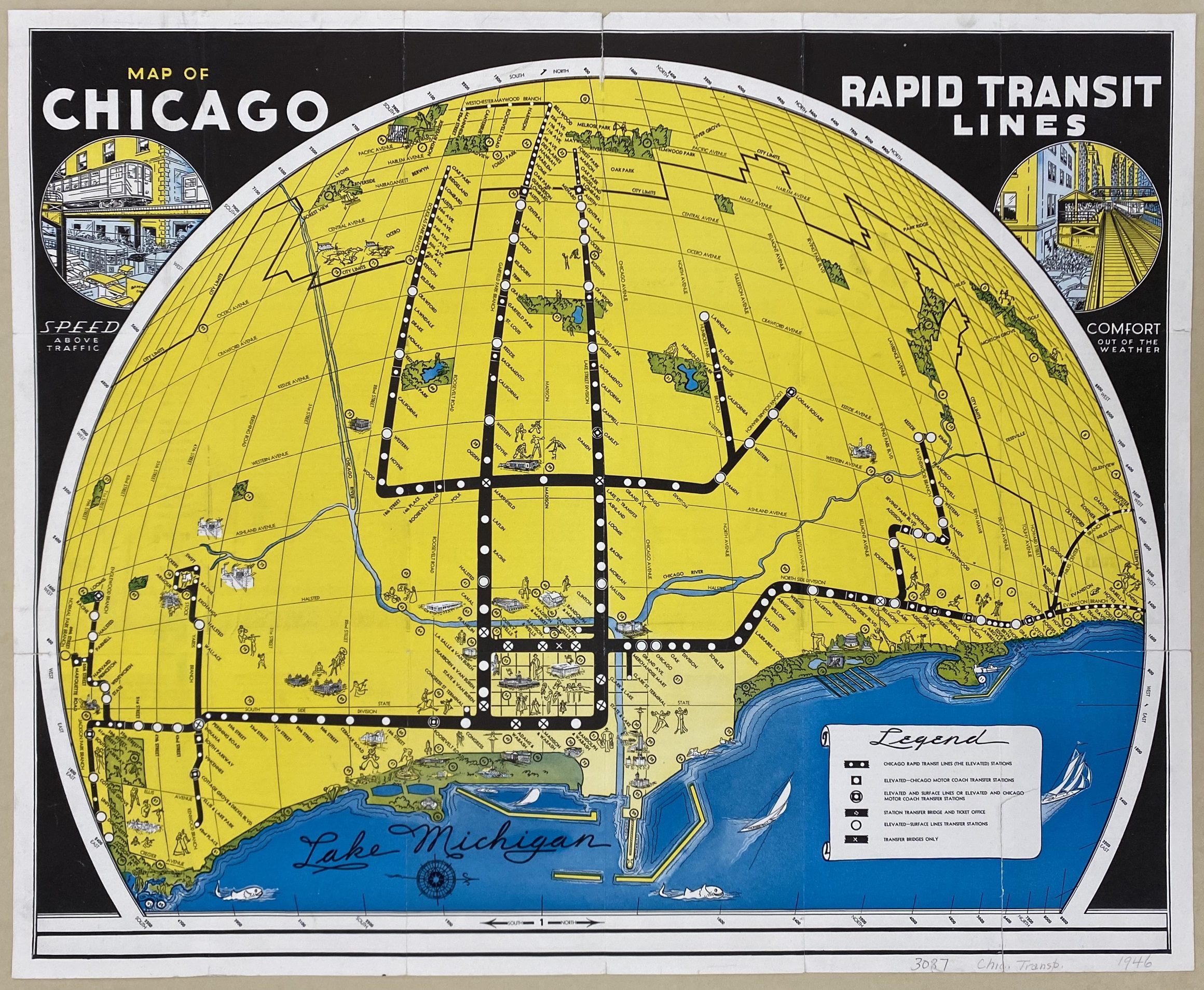

A Chicago Rapid Transit Lines map with a fish-eye style design, 1946.

What’s your favorite artifact?

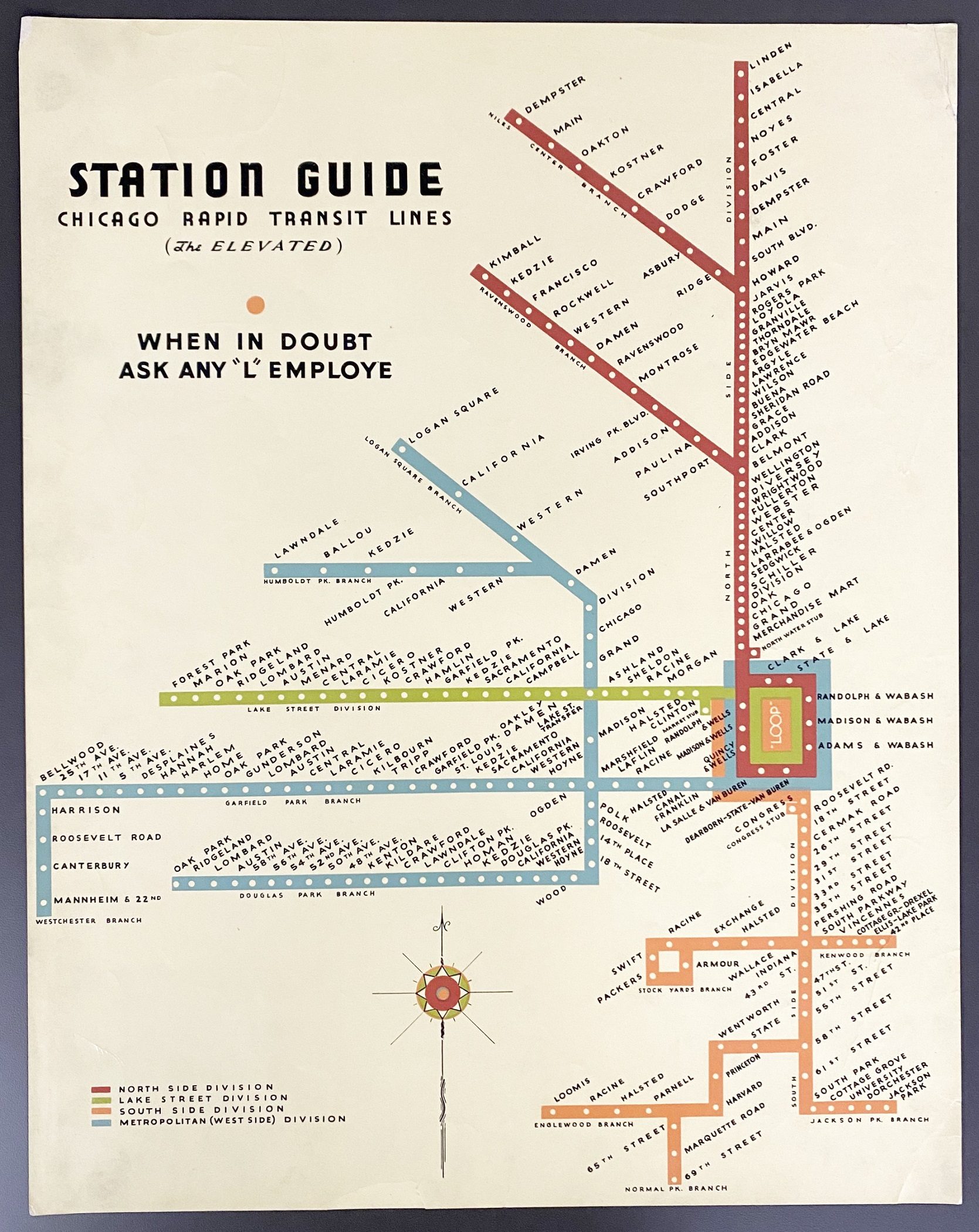

This changes all the time, depending on what I’m working on. Last month, I was pulling out some transit maps. I am a big fan of public transportation (I haven’t owned a car since my first and only automobile died around 1990.) I love looking at the ways Chicago’s transit has changed over the decades, and also the ways it has stayed the same. And I love looking at how graphic designers have conveyed the information. (Spoiler alert—thanks to a National Endowment for the Humanities grant, many of our pre-1940 maps will be available to view online in fall 2024 through a partnership led by the University of Chicago and including the Newberry Library.)

A Chicago Rapid Transit Lines station guide, 1936.

What will you miss about CHM?

I’ll miss working with colleagues throughout the building, but especially my coworkers in the ARC. I’ll miss the community of researchers who made my job so interesting (and were so helpful—often, as one researcher was asking a question, another might pipe up with a useful contact or suggestion). I guess this is my opportunity to switch sides again—I look forward to coming in and doing research from the other side of the reference desk!