Artifact Conservation and Preparation at CHM

Even in the most ideal environmental conditions, time takes its toll on museum artifacts. Museum conservators play a critical role in ensuring the longevity of these special objects, so they can be enjoyed, studied, and admired by future generations.

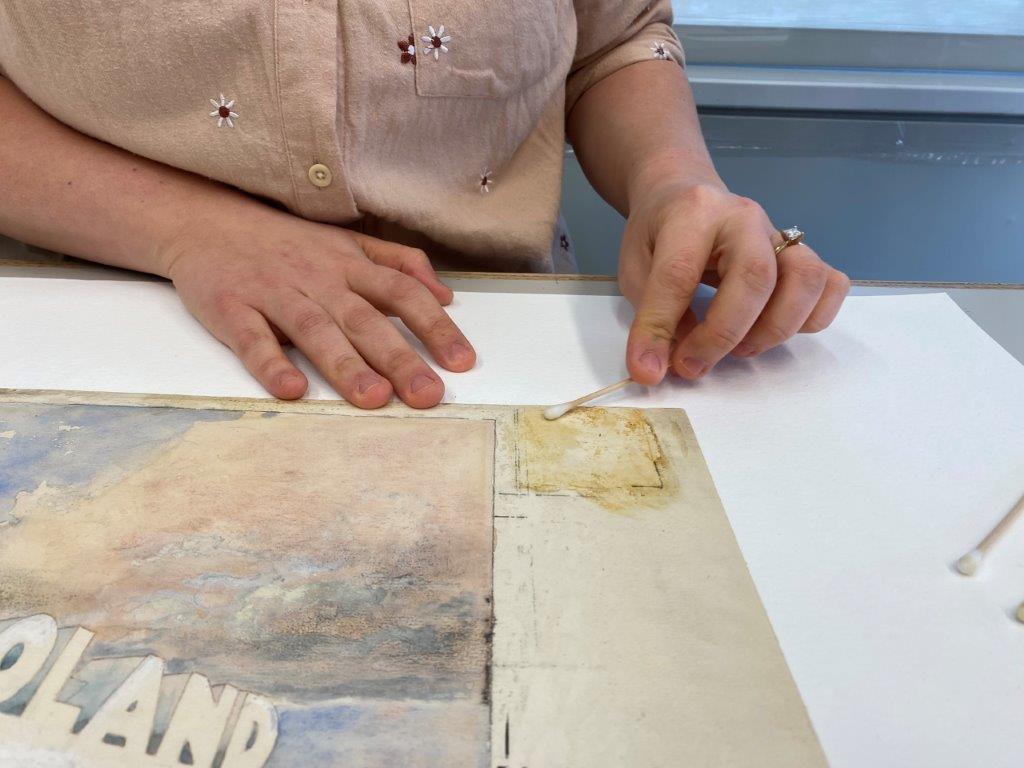

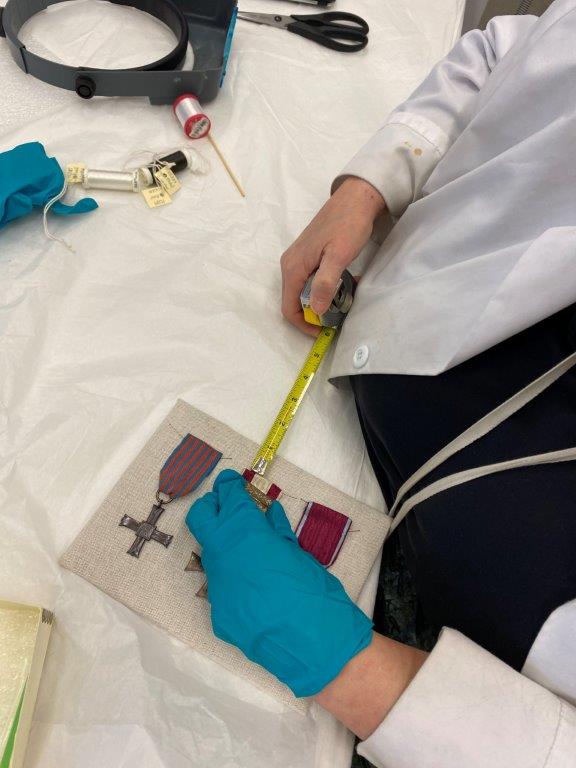

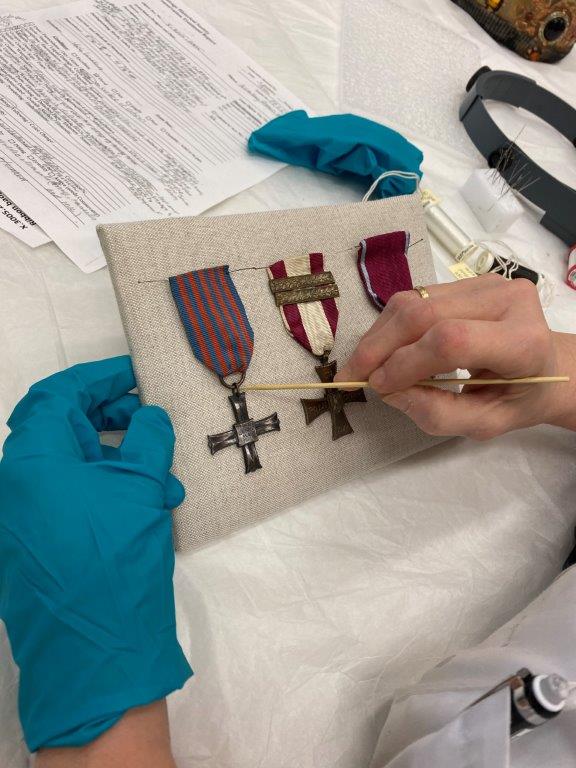

Any object that is considered for display in an exhibition, whether from the Chicago History Museum’s collection or a special loan, is brought to the conservation lab to be assessed for its current condition and any treatment needs. Treatment might include low-suction vacuuming to remove dust, adding support fabric to reinforce damaged textiles, softening and laying down paint fragments that have lifted, and so much more. The condition and treatment of each object going on display is carefully catalogued so conservators can track any changes in the object’s condition.

Another critical part of conservation work is establishing the best parameters for an object’s display by ensuring it is stable enough to withstand handling and mounting for exhibition, as well as taking steps to limit its exposure to light and dust when on display.

Many items in CHM’s collections need custom-made mounts for exhibition display. Mannequins are also frequently modified to fit garments and evoke the silhouettes of their respective time periods. As you can see, it takes tremendous time and effort behind-the-scenes before objects can be shared with visitors.

To learn more about conservation at CHM, check out the blog posts and image galleries below.

Learn more about past conservation projects

Hear more from CHM conservators

What is the most difficult material you’ve had to take care of and why?

What’s the most time-consuming project you’ve worked on?

What advice would you give people to keep old objects or family heirlooms in good condition?

How do you balance conserving an object with maintaining its historical integrity?

Do you ever find a piece to be irreparable? And if so, what does CHM do with it?

Recent Projects

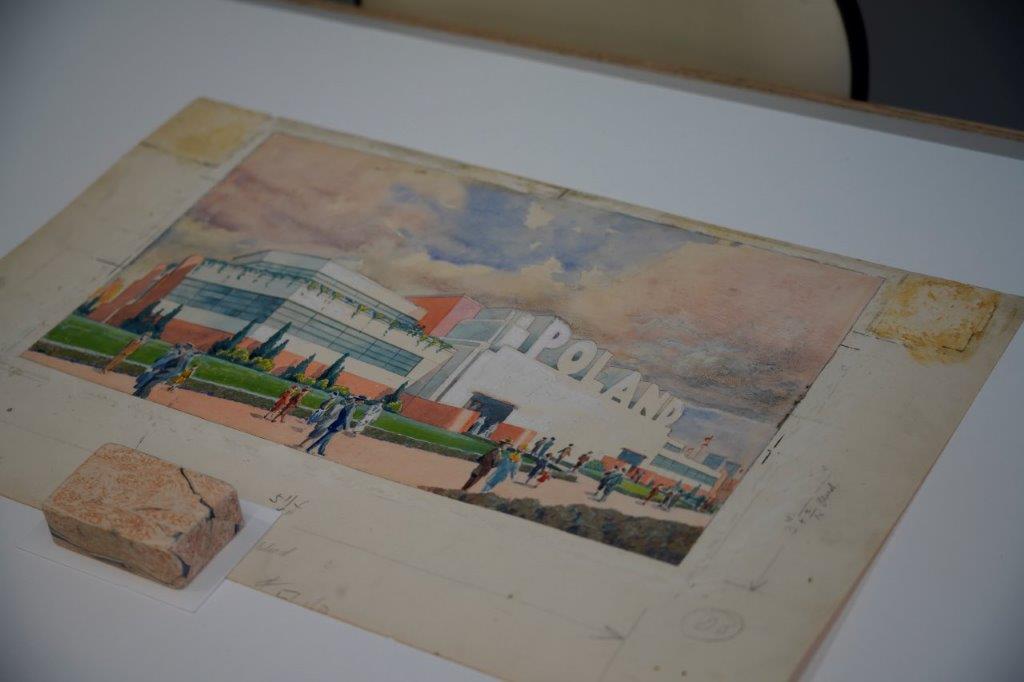

Check out the photo stories below for a look at projects CHM conservators have worked on for Back Home: Polish Chicago.