October is LGBTQIA+ History Month. In this blog post, CHM senior public and community engagement manager Greg Storms writes about Gregory A. Sprague, a Chicago historian of gay culture who laid the foundation for a comprehensive historical account of queer people.

Looking back at my nearly two-decade career in LGBTQIA+ history and education, I draw inspiration from a number of my predecessors. That’s easier when looking at a national or even global level, but studies of Chicago’s queer communities and their histories took longer to become established than other regions. In fact, one of the reasons I specialized in researching Chicago was to help lift up Midwest LGBTQIA+ research. Unfortunately, those who have historically studied our city’s queer history have not gotten the acclaim we see elsewhere. One such figure is Gregory Sprague.

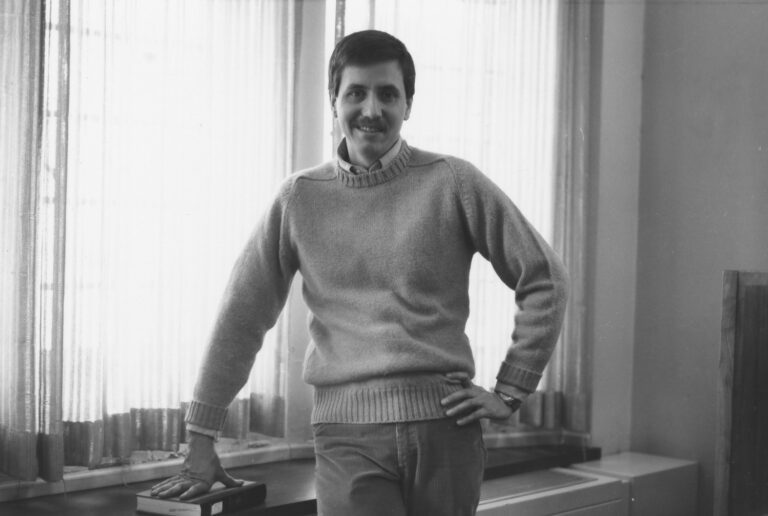

Gregory A. Sprague in front of a window, c. 1980. CHM, ICHi-065053. Gift of Robert C. Peppard and Edward Warro. 1987.627. Gregory A. Sprague papers, box 2, F. 1 – Misc. personal photographs

Born in 1951, Sprague earned a BA in history from Augustana College in 1973, a MA from Purdue University in 1975, a Master of Science in Education from Indiana University in 1976, and pursued a PhD at Loyola University Chicago (1980–85). He is remembered for his historical research on Chicago gay and lesbian history, but perhaps of greater long-term importance than his actual research was his work in creating systems for supporting LGBTQIA+ history as a materially supported subset of historical inquiry more broadly.

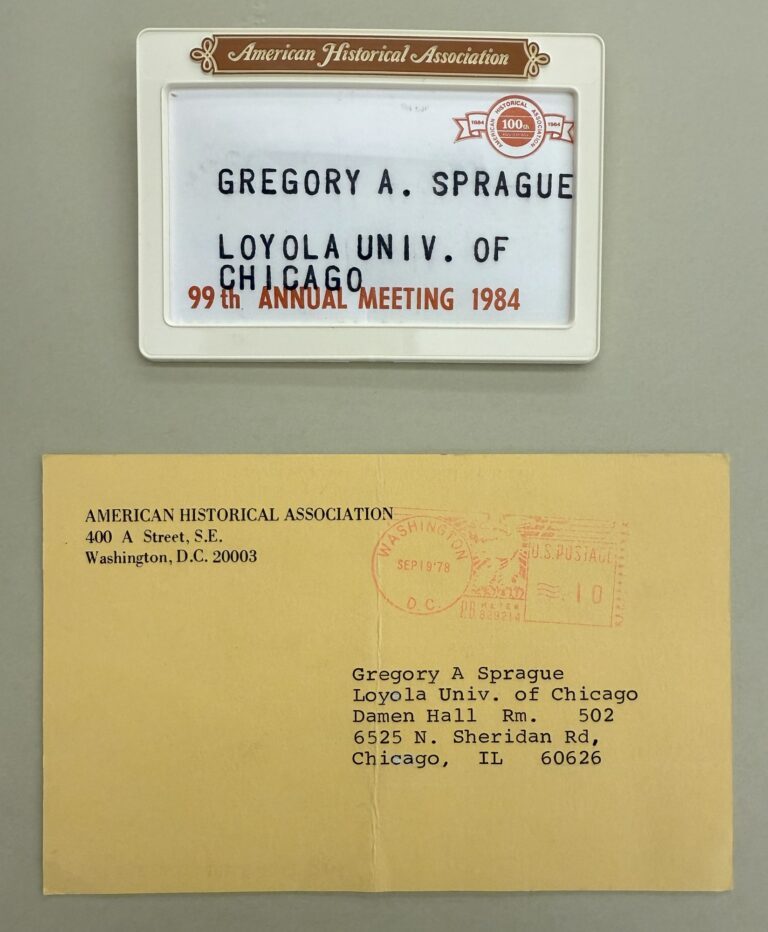

Two items related to Gregory Sprague’s membership in the American Historical Association—a name tag from the 1984 annual meeting and a postcard from 1978. Gregory A. Sprague papers, box 21. Photograph by CHM staff

In addition to being a cofounder of the American Historical Association’s (AHA) “Committee on Lesbian and Gay History” (now known as the LGBTQ+ History Association, an AHA affiliate), Sprague founded the Chicago Gay History Project in 1978. This volunteer-led group would become a precursor to Chicago’s premier LGBTQIA+ historical archive, the Gerber/Hart Library. He also served on the national board of directors of the Gay Academic Union (GAU, 1973–87) for several years and on the steering committee for the Chicago chapter. He was also the program coordinator for one of the GAU’s national conferences held here in the city.

Crowd of people at gay rights rally at Daley Plaza, Chicago, April 1981. CHM, ICHi-039699. Gregory Sprague color slide collection: Box 2

For some context, LGBTQIA+ history, and indeed most all academic research conducted by and for queer people, did not develop until the 1970s. As a result of significant social activism following the Homophile Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, liberation-centered activism and approaches to queer social existence developed by and in tandem with many other social movements, both nationally and globally. For example, the rise of the Black Power Movement, women’s liberation, youth-centered social movements, the anti-Vietnam War movement, and global efforts at decolonization all contributed to the shift from the more assimilationist approach of earlier fights for LGBTQIA+ people to the rise of the gay liberation movement of the late 1960s and especially the post-Stonewall period after 1969.

Undated photograph of Gay Pride Parade marchers carrying Illinois Gay Rights Task Force banner, Chicago. CHM, ICHi-050720. Gift of Robert C. Peppard and Edward Warro. 1987.627. Gregory Sprague color slide collection: Box 1, red binder

Part of this work was to develop a comprehensive historical account of queer people despite the continuing impact of structural homophobia (and biphobia and transphobia) embedded within society at large and institutions of historical inquiry specifically. To be blunt, studying LGBTQIA+ history—especially in an affirming way—was a career killer. Like many researchers of marginalized backgrounds who study their own communities, at best accusations of bias created barriers for professional growth.

With this in mind, people like Gregory Sprague become special figures within LGBTQIA+ communities, helping lay the groundwork from which the general public can find real and often positive representations of people like them that had been previously denied. Even today, with the impressive growth of the field, there is a continuing need for and importance of this type of historical work—work that is not only LGBTQIA+ history, but Chicago history, US history, and global history, all in one.

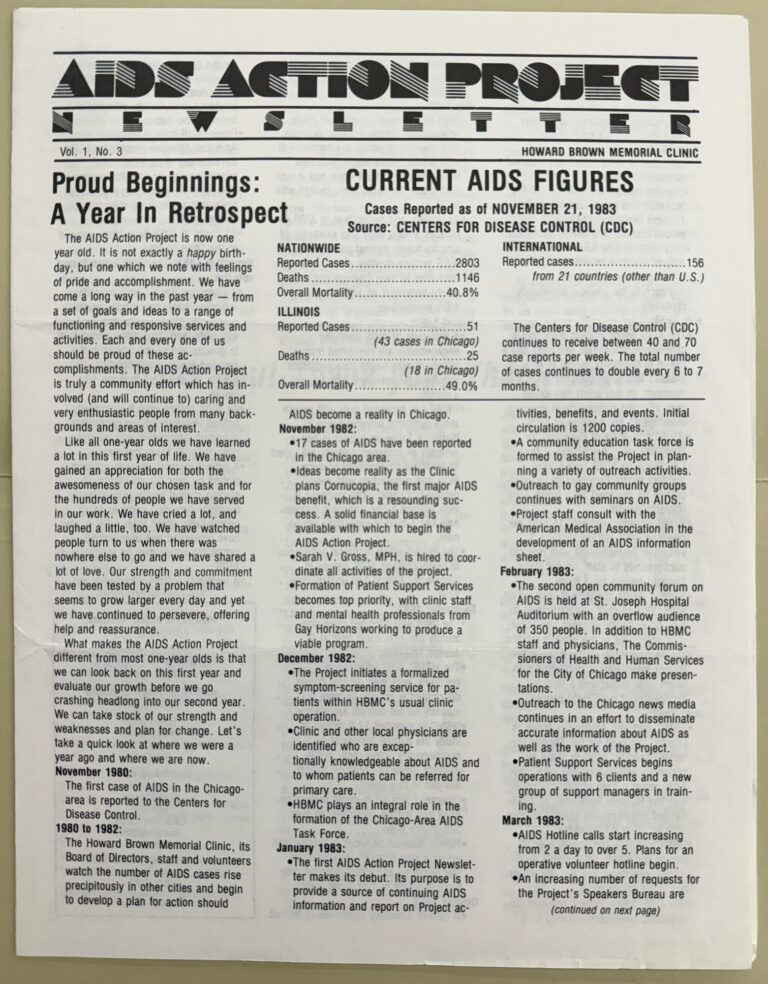

AIDS Action Project Newsletter, vol. 1, no. 3, 1983, which documented the AIDS epidemic and reaction to it on national and local levels. Gregory A. Sprague papers, box 21 Photograph by CHM staff

Like so many other gay men of his generation, Sprague did not live past the 1980s. On February 7, 1987, he died of complications related to HIV/AIDS. Many younger LGBTQIA+ people depend heavily on the work and legacies that researchers like Sprague leave behind. Unlike many other communities, LGBTQIA+ folks are typically not taught their history either in school or through familial channels. For gay and bisexual men especially, nearly an entire generation of people who could have formed that bridge between older generations and those born after the late ’70s simply weren’t there due to the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Thankfully, Sprague’s work has been preserved in a number of ways. Both the Gerber/Hart Library and Archives and the Chicago History Museum retain collections of Sprague’s materials. The Gregory Sprague papers [manuscript], 1972–87, include materials written and collected by Sprague, such as his diplomas, transcripts, correspondence, and topical files containing photocopied articles and book chapters pertaining to his research. The Gregory Sprague photograph collection (c. 1975–87) documents his personal life in Chicago during that time, as well as social events such as the Gay Pride Parade. Both collections can be accessed at CHM’s Abakanowicz Research Center, which is free to visit.

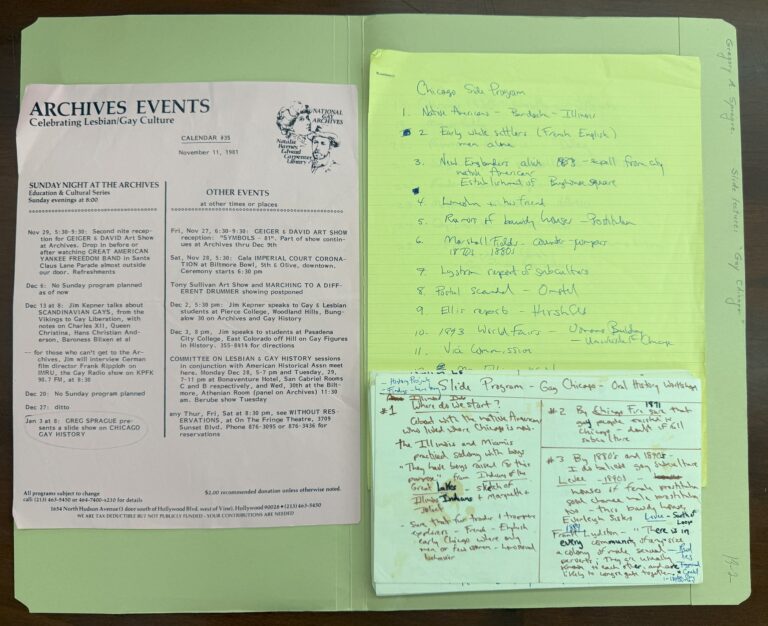

An event calendar (left) for Sunday Night at the Archives: Education and Cultural Series in Los Angeles, November 11, 1981. Sprague presented a slide show titled “Chicago Gay History” on January 3, 1982; his lecture notes are on the right. Gregory A. Sprague papers, box 13. Photograph by CHM staff

While he may have lived in Chicago for only a decade, his impact remains palpable. His legacy goes on through the evolving landscape of organizations that continue doing the critical work of documenting, representing, and preserving queer history. Sprague’s reputation lives on through the LGBTQ+ History Association’s biannual Gregory Sprague Prize, which recognizes “outstanding published or unpublished” work by graduate students on LGBTQIA+ history in English. He was posthumously inducted into the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame in 1994, where he is remembered for “(knowing) that the history of lesbians and gay men in Chicago was being carefully tended in lifetimes of memories, and he was instrumental in gathering those memories.” And his role in “gathering those memories” continues to shape the work that I and a growing number of LGBTQIA+ scholars and educators do to this day.

Additional Resources

- Read more blog posts on LGBTQIA+ history

- Listen to Studs Terkel’s interviews with LGBTQIA+ activists, artists, and writers of the mid to late 20th century