Jojo Galvan Mora joined the Chicago History Museum (CHM) in 2021 as a researcher for Chicago00. In this blog post, he talks about his path to CHM and his work on our upcoming exhibition Aquí en Chicago.

What led you to the Chicago History Museum?

I began collaborating with the Museum on some digital humanities projects right around the time COVID-19 pandemic restrictions were easing up. One thing led to another, and then I found myself here in my current position of Digital Humanities Fellow. The history of Chicago and the surrounding area had always been a big interest of mine during my time as an undergraduate, and it only grew stronger as I matriculated through grad school. Ultimately, the wind blew me in the right direction!

When did you realize that you wanted to pursue a career involving history?

In a way, I’ve always known, which has often been both a blessing and a curse. Stories that transcend time or help us better understand our current moment have always fascinated me. I’ve always been a collector of just about anything that catches my interest: rocks, toy cars, bottle caps, books, furniture, etc. Growing up, we moved around a lot for a number of reasons, and that often meant leaving collections behind because I couldn’t take everything with me. That also meant that wherever we landed, I’d have the opportunity to start new collections.

Over the years, it wasn’t just about collecting things I could touch or hold, but things that I could carry with me wherever I went, like bits of folklore or urban legends. That interest only grew with time, and while it was helpful in giving me a rough idea of the trajectory I wanted to have, it also meant accepting that the journey in front of me was not going to be an easy or straightforward one. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve learned not to hold my breath and just let things go where they will.

Today, I’m working on finding a way to make our ever-increasing digital footprint as an institution more sustainable and accessible. Tomorrow I could be in someone’s residence because they reached out to the Museum and wanted to donate material related to an obscure topic that I just happen to know a lot about. The love of things of this world and the people behind them is what has kept me here.

Why is translation work important to the museum field?

The short answer to this question is straightforward: translation work is vital because museums should be welcoming to all, regardless of what language they speak. It’s our responsibility as cultural workers to do everything within our grasp to make the Museum’s galleries welcoming to everyone curious to learn.

The lengthier answer is one full of nuance. If we focus on Chicago, the data presents a compelling case. As of 2020, one in every three Chicagoans over the age of five speaks a language other than English at home. According to a 2025 Language Needs Assessment Report commissioned by the Illinois Governor’s Office of New Americans, in Cook County alone, there are almost 700,000 individuals who the census identifies as “Limited-English” persons (individuals who do not speak English very well, if at all). Out of that sum, more than half of those individuals (roughly 400,000) speak Spanish at home.

By comparison, the second most spoken language in Cook County is Polish, with almost 49,000 speakers. In our present-day world, translation/multilingual resources, as well as education, have become the standard in school classrooms, government offices, and faith-based and social service organizations. Suppose we’re taking seriously the promise of museums as sites for civic engagement, community connection, and individual empowerment. In that case, the importance of translations in galleries and educational materials quickly becomes non-negotiable.

Going beyond the numbers, our reality at the Chicago History Museum is that the history shared in our galleries extends beyond the United States. Chicago is, and has always been, a global city. Therefore, it’s not uncommon for us to encounter languages other than English in our research and Museum collections. Whether it’s Spanish, Polish, Vietnamese, Arabic, or one of the many Indigenous languages spoken here long before the arrival of outside settlers, the city and the region’s history haven’t been recorded or understood exclusively in English. As the museum tasked with interpreting the city of Chicago’s history, telling a more accurate and encompassing story demands that we go beyond the English language.

Tell us a little about your contributions to the Aquí en Chicago exhibition.

Well, I think my most obvious contribution to Aquí is the Spanish label text in the gallery and exhibition catalogue. While I’ve translated entire exhibitions, both in and out of CHM, Aquí is undoubtedly the largest translation project I’ve ever led. Outside of that, my fingerprints are all over the exhibition. I loaned a few works of art for the show. I led the research for some artifacts and helped with the acquisition process for others. My favorite contribution comes from the two summers I spent mentoring Aquí summer interns with my colleague, Dr. Elizabeth Barahona. It’s a great feeling knowing that I had the tiniest bit of influence in helping the writing process for the next generation of storytellers.

Jojo Galvan Mora (left) at a community collections workshop held at the 18th Street Casa de Cultura, which taught members of the general public how to best preserve their family heirlooms, Chicago, 2023. Photograph by CHM staff

Do you have a favorite object in the exhibition or is there a part of the exhibition that resonates most with you?

There isn’t anything in Aquí that doesn’t resonate with me! Everything included was carefully selected. However, an object that is both incredibly important to me and likely to be overlooked by many guests due to its small size is the air quality sensor we borrowed from the Cicero Independiente.

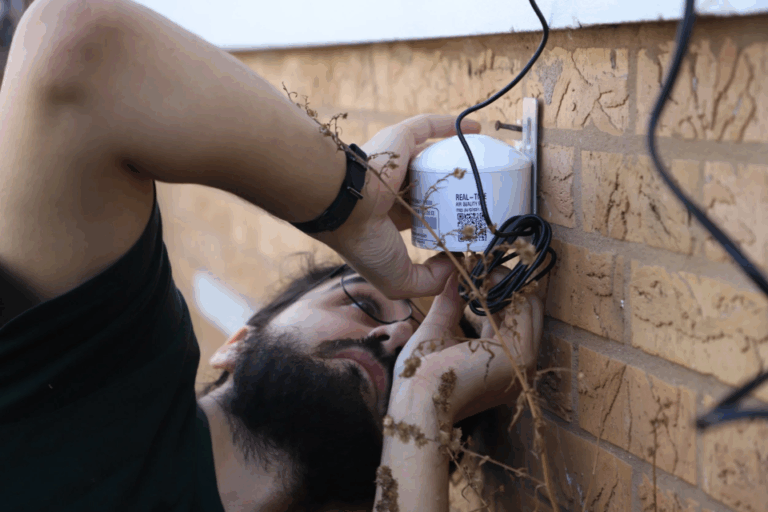

Cicero Independiente air sensor installation, 2023. Photograph courtesy of the Cicero Independiente

This small sensor was one of several that the newspaper’s reporters installed across the homes of Cicero residents, as part of a project focused on monitoring the town’s air quality. After roughly a year of data collection, what they discovered was devastating. It wasn’t uncommon for the data to show that Cicero regularly had the worst air quality in the area. As a result of the paper’s coverage, the issue garnered widespread attention, shedding light on decades of environmental injustice suffered by residents. While the Independiente’s work on this is far from finished, this investigation and the many others their newsroom have published demonstrate one of the many ways that change comes about through community work and resistance. Issues like air quality or access to local health data don’t impact specific neighborhoods and ignore others. They should be of interest to all of us.

What is one thing you hope people will learn when they visit the exhibition?

Outside of the rich history presented in the galleries through artifacts, images, and label text, I want Museum guests to walk away and truly consider the city’s future. While the stories in Aquí illuminate close to two centuries of Latino/a/e presence and resistance in Chicago, we’re also putting forward a compelling hypothesis: the future of Chicago is Latino/a/e. I hope that this idea inspires Museum visitors to learn more about and immerse themselves in the diverse cultures from all across Latin America that are breathing new life into the city’s neighborhoods.

Tell us about some of the connections you’ve made with community members while working on Aquí en Chicago.

There are far too many connections to count! From bringing the Hojarasca® cookies created by the Bonilla family, proprietors of the El Nopal® Bakeries in Chicago out of retirement and into the Museum’s North & Clark Café or interviewing members of the Alcala family about their legendary western wear store, it’s been an amazing experience.

However, if I had to choose a favorite connection, it’s undoubtedly building the link to the beautiful relationship that has blossomed between the Museum and the Kichwa Community of Chicago, an organization focused on the cultural preservation of Indigenous community practices from Ecuador.

Kichwa mural in Chicago, July 1, 2025. Photograph by CHM staff

Through this partnership, the Museum was able to collaboratively publish a trilingual (English, Spanish, and Kichwa) article in Chicago History magazine in 2025, detailing this community’s history and culture and expand the Museum’s collections by adding traditional Kichwa men’s and women’s ensembles to our costume collection. I’m excited to see how these relationships continue to develop long after the exhibition closes.

Five Favorites

- Favorite ice cream flavor? Most days it’s vanilla. Every now and then a seasonal fruit flavor catches my heart.

- Favorite season? Fall, always and forever.

- Favorite animal? I have a thing for animals that are “ugly cute” like hyraxes and capybaras.

- Favorite book? Too many to list, so I’ll keep it to stuff that I read as a child but continues to resonate with me into adulthood: The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, Neighborhood by Norbert Blei, and the entire Michigan Chillers series.

- Favorite place to vacation? Anywhere with bodies of water. Michigan is always in my top five, but I’ve also come to love the Pacific Northwest, from Vancouver to Cannon Beach.