This summer, CHM collections intern Brittany Boettcher worked with senior collections manager Britta Keller Arendt to inventory items in our Decorative and Industrial Arts collection. In this blog post, Boettcher highlights some Civil War artifacts and explains how differences between Confederate bills answered the questions she had about where and when they were printed. CHM publications intern Lily Stachowiak helped organize and publish this blog post.

Inventory projects in museums are like opening up a box of chocolates because you have no idea what you’re going to find. Museums conduct regular inventories of their collections in an effort to improve intellectual control and track locations of artifacts throughout their facilities. The Decorative and Industrial Arts (DIA) collection at CHM comprises approximately 100,000 artifacts, most of which have not been inventoried in recent years. Over the course of the summer, our goal was to document the artifacts stored throughout one aisle of shelving units. We found a huge range of items such as souvenirs from the 1893 world’s fair, Day of the Dead figurines, and a picture frame made by Civil War POWs.

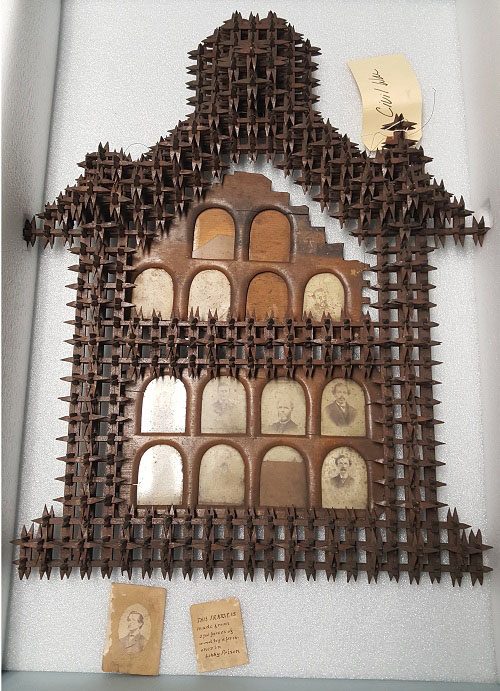

Union POWs at Libby Prison in Richmond, Virginia, made this picture frame with iron nails. The photographs are called carte de visites (CdVs), which were popular during this era. All photographs by Lily Stachowiak

My fellow intern Cara Caputo and I learned something new every day as we cataloged our findings. Our tasks included inspecting objects, recording a description, take dimensions, and photograph them to add to or update the Museum’s digital records. This is so Museum staff can locate artifacts in the collection more easily and scholars can better research the collection. Throughout this process, it was important to be patient and detail-oriented. Sometimes we knew exactly what an object was, such as colonial currency from the Revolutionary War, but other times we needed to conduct research to learn more about the function or importance of the object.

For example, we slowed down when we found an envelope filled with twenty-one Confederate bills of varying sizes and denominations. Since they all came from southern states during the period of the Civil War and were in the same envelope in a box filled with other money, it was very tempting to take one picture and catalog all of them in one record. However, I realized it was important to take the time to study the bills individually—when I did so, it was clear the variations between them were likely significant.

Currency from various Confederate states in different denominations.

A close-up shot of two Confederate bills.

While these two bills can both be classified as Confederate currency, there are a number of important differences between them, includes size, design, printing date, and location.

During the Civil War, the government of the Confederate States of America printed its own currency that looked like the bills we found in our collection. Due to the limited amount of metal available at the time, only paper currency was printed. Also, the majority of printing presses were in the North, which meant that the Confederacy had a limited amount of design elements available for use. As a result, they reused familiar images and designs of goddesses of agriculture, commerce, and liberty, as well as important Southerners like Jefferson Davis and his cabinet members. Eventually, individual states, banks, and even private citizens started printing their own bills. The combination of inflation, a lack of gold and silver to back the money, and the Confederacy’s loss in the Civil War made these bills almost worthless. Nevertheless, the different designs, print dates, and sources of these paper bills can help identify the political and social environment in which they were created, the rarity of these bills, and much more.

Because of the significance of the various designs, we took time to update records and take individual pictures of each bill. If we had quickly grouped them together in a record and taken one photograph of all the bills, it would be harder for others to study them. Working with these bills taught us patience, which we used throughout the rest of the project. This internship also taught me more about history and good practices for collections management. I can only hope our effort and attention to detail will someday help others learn more about history through our collection.

- Read more blog posts about CHM’s inventorying efforts

- For more about Confederate and other historic currency, check out the National Museum of American History’s online exhibition

Join the Discussion