In this photo essay, take a look back at the events surrounding the infamous 1919 Black Sox scandal. The text is adapted from “Black Sox” by Robert I. Goler, which appeared in Chicago History, fall/winter 1988–89.

One hundred years ago, the Chicago White Sox lost the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds. The infamous series has come to be known as the Black Sox scandal due to a group of eight White Sox players (dubbed the Black Sox by the press) allegedly agreeing to throw games in exchange for money from a group of high-stakes gamblers.

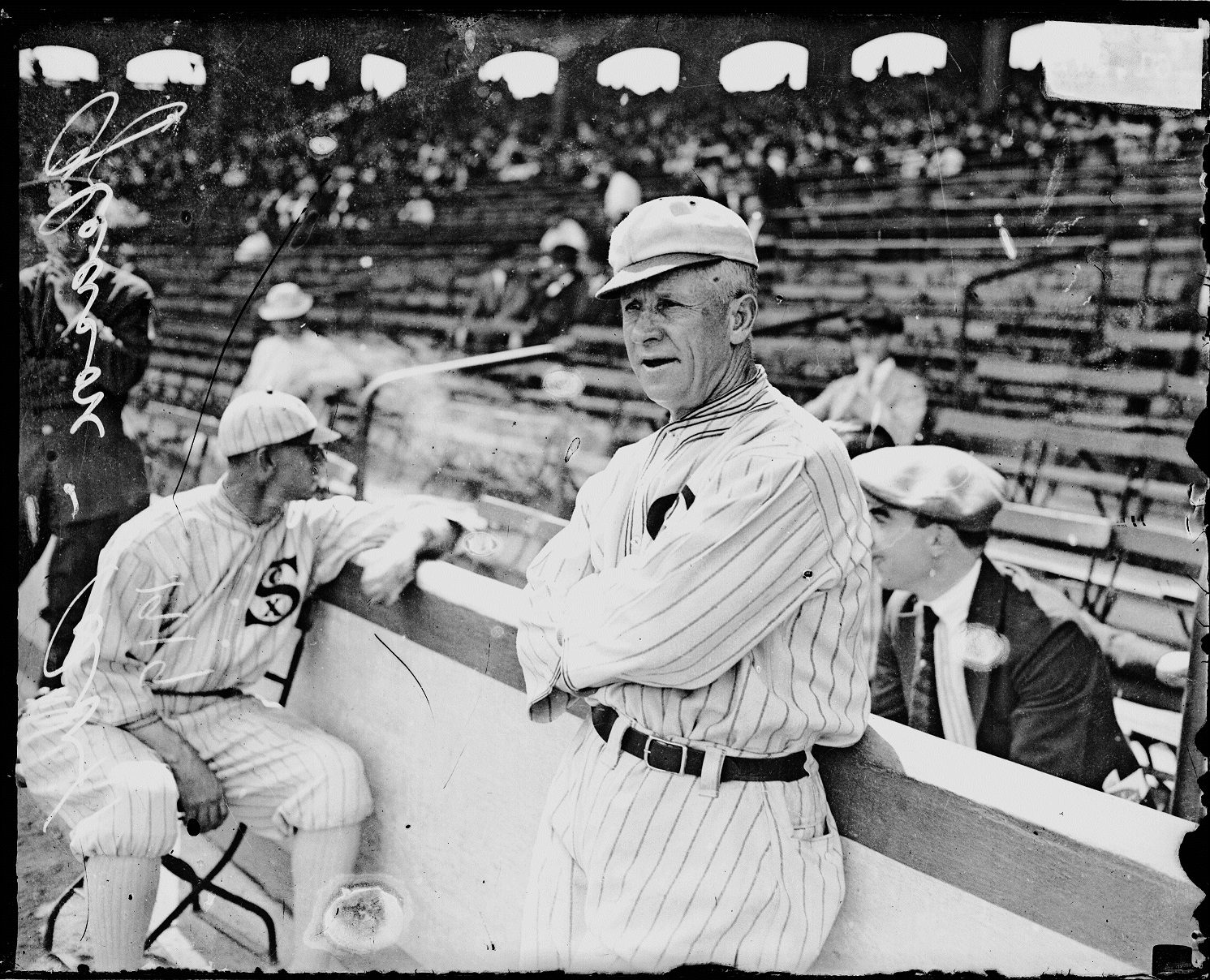

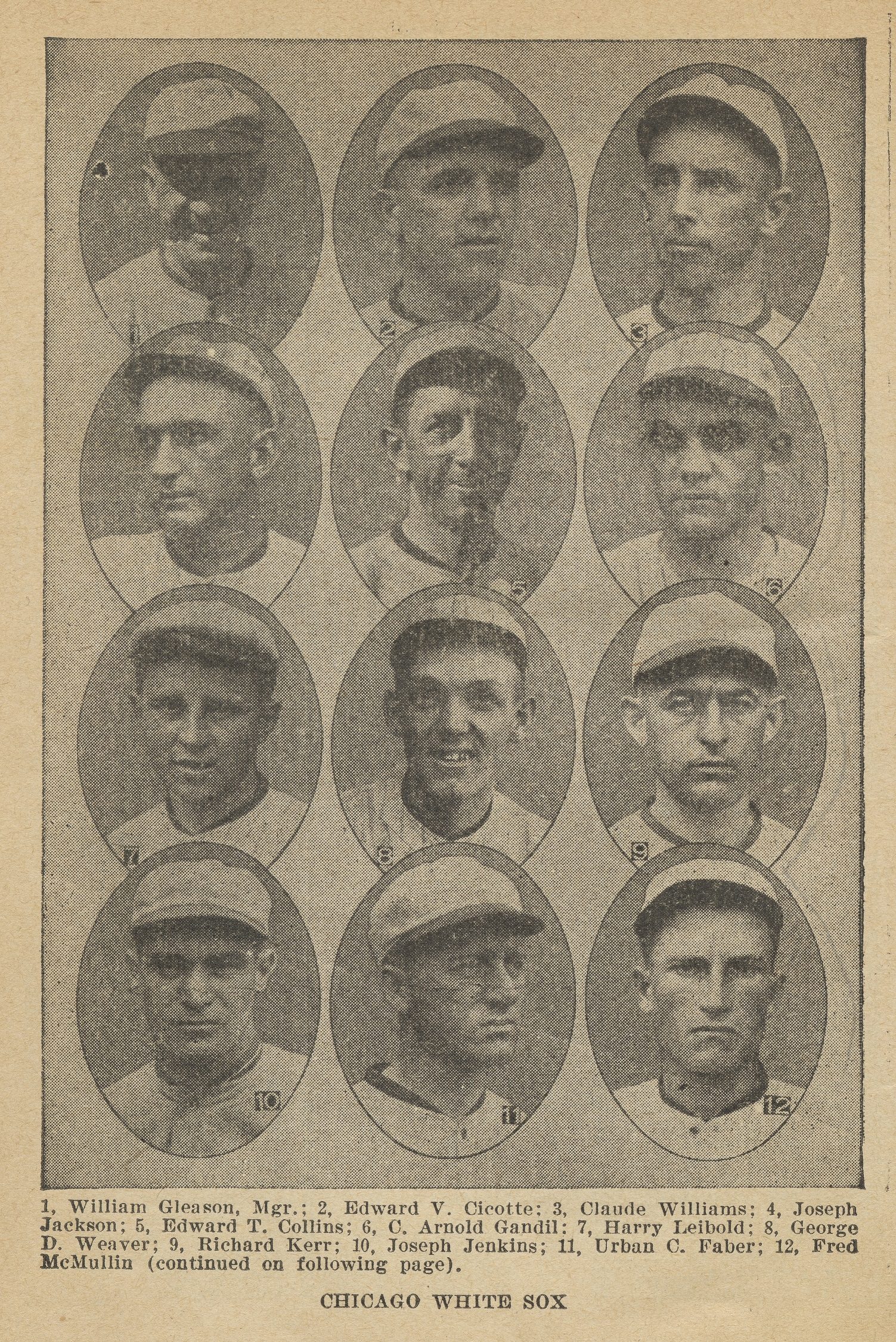

The White Sox had won the World Series in 1917. Their 1919 lineup was similar to that championship team, but they had new manager in William Kid Gleason.

Kid Gleason at Comiskey Park, 1919. SDN-061872, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

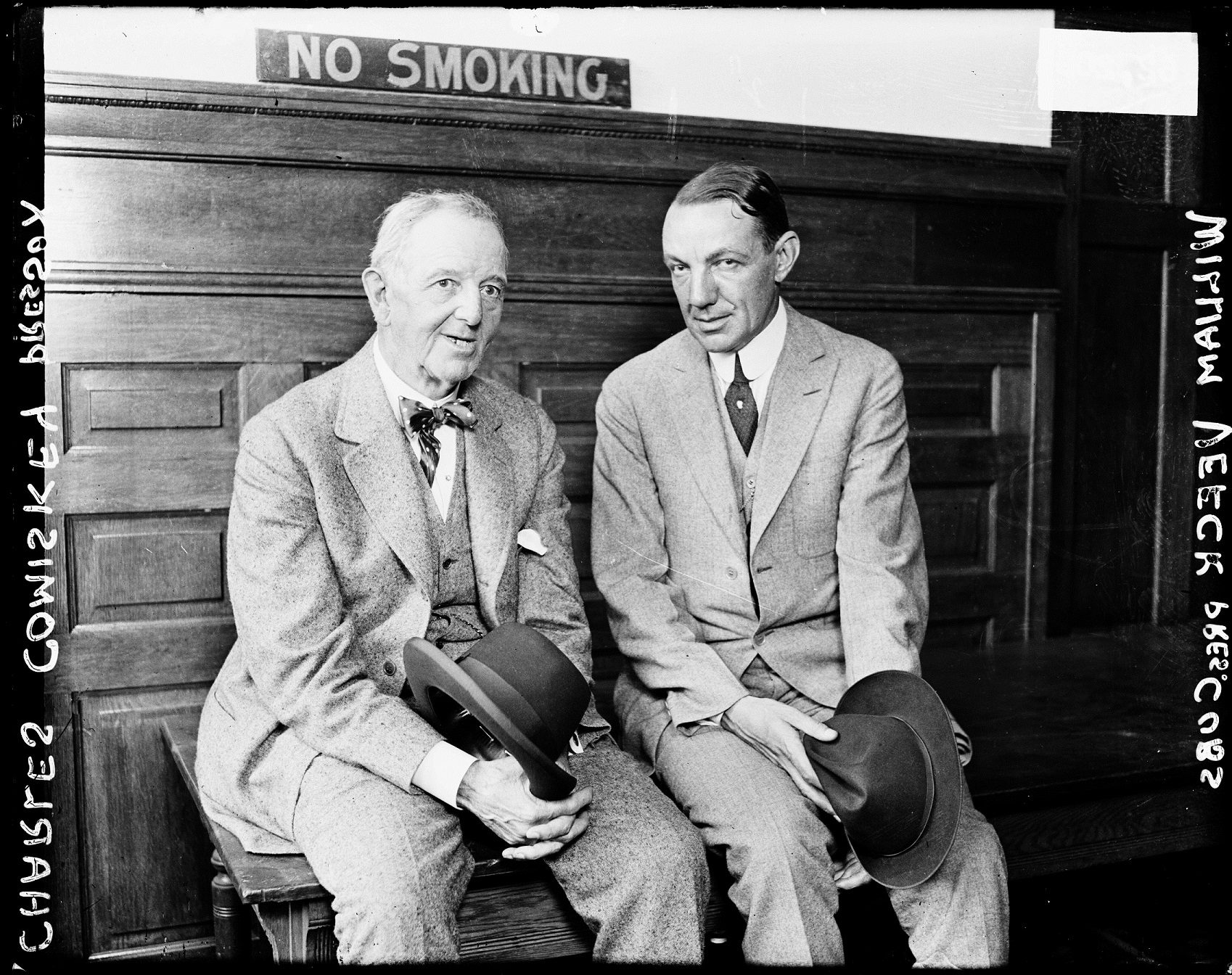

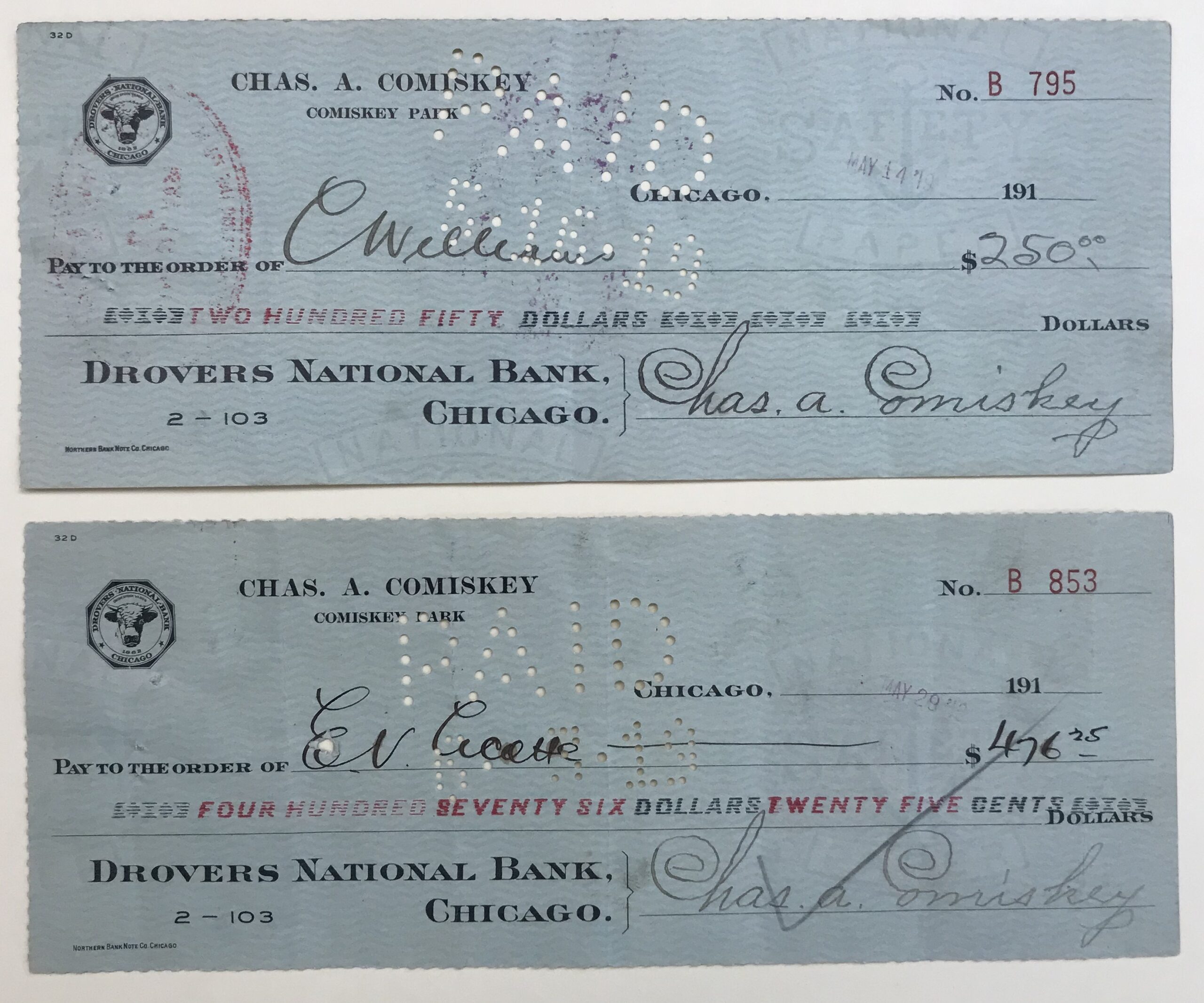

Among the myths surrounding the scandal is the notion that low salaries and team owner Charles Comiskey’s frugality angered some of the players. While it was true that without a union they had little bargaining power, White Sox players’ salaries were comparable to others in the league.

Comiskey, left, and Bill Veeck Sr., president of the Chicago Cubs, 1920. SDN-062205, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

Paychecks (1919) signed by Comiskey and endorsed by players Cicotte and Williams, Chicago White Sox and 1919 World Series baseball scandal collection, 1917–1929, CHM

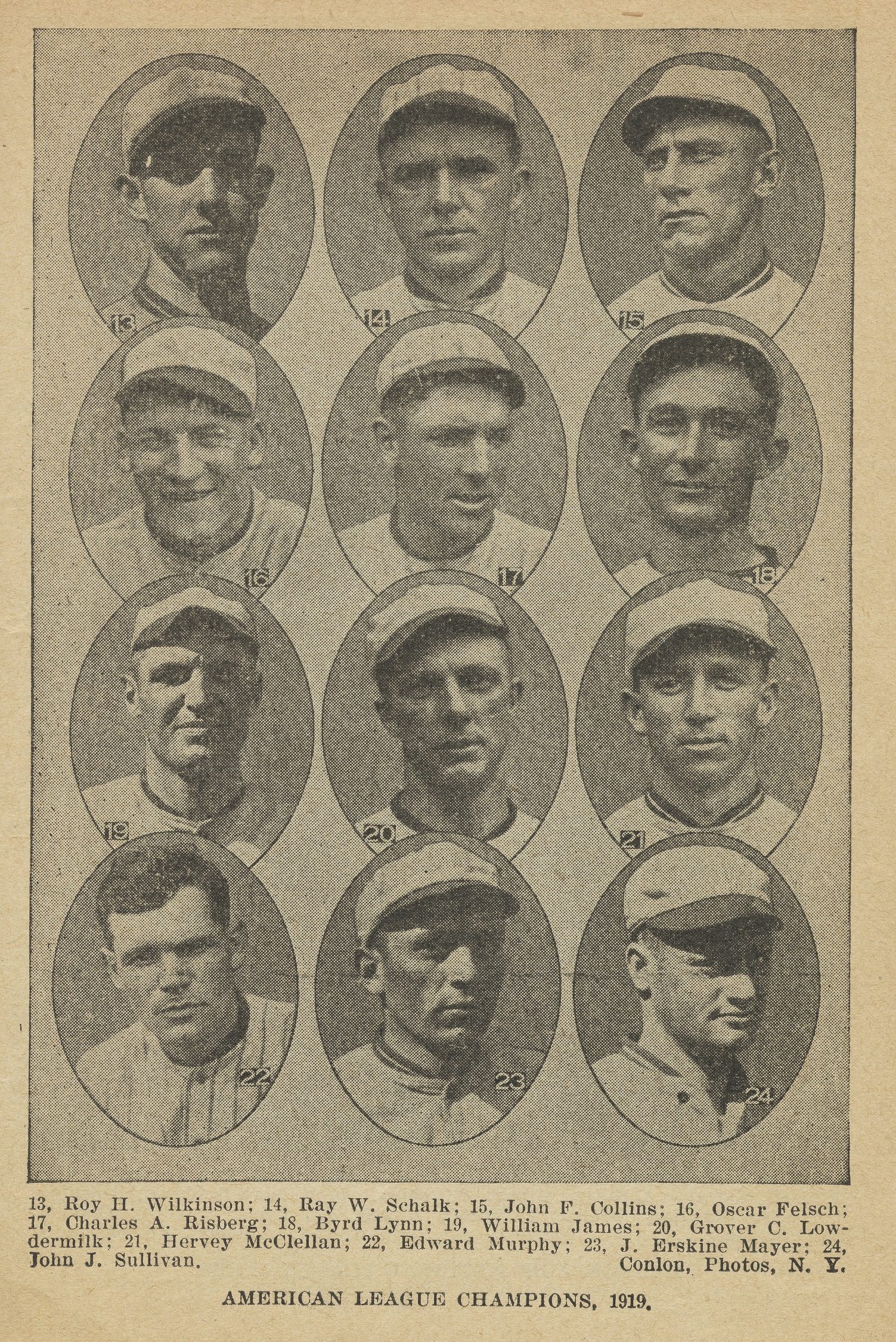

In 1919, the White Sox were the American League champions with a record of 88–52. Their lineup included the hitting power of star player Shoeless Joe Jackson, second baseman Eddie Collins, and pitching aces Eddie Cicotte, Claude Lefty Williams, and rookie Dickie Kerr.

The 1919 American League champion White Sox. CHM, ICHi-067451, ICHi-067452

The Sox were set to face the National League champion Cincinnati Reds, who had a record of 96–44 and the franchise’s first pennant. The 1919 World Series was a best of nine games and the first one since the end of World War I, so fans around the country followed it closely.

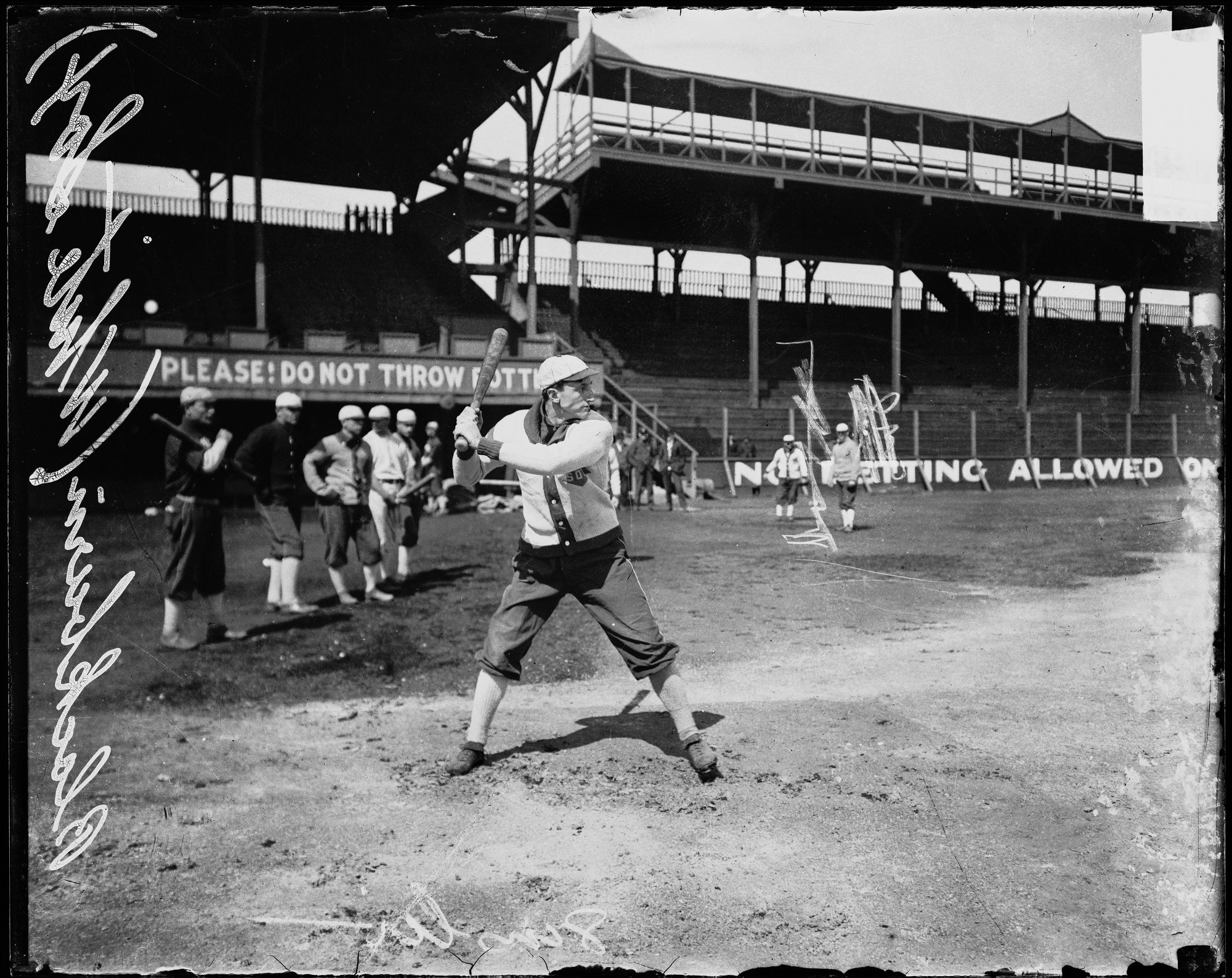

Baseball and gambling had been intertwined since the game’s beginning, and gamblers often attended games. In 1910, Comiskey even had a large sign painted down the left field line of South Side Park that proclaimed, “No betting allowed in this park.” Even so, fixing games was a long-suspected practice.

Lena Blackburne at home plate in South Side Park. Start of “No Betting Allowed” sign visible in back, June 11, 1910. SDN-056014, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

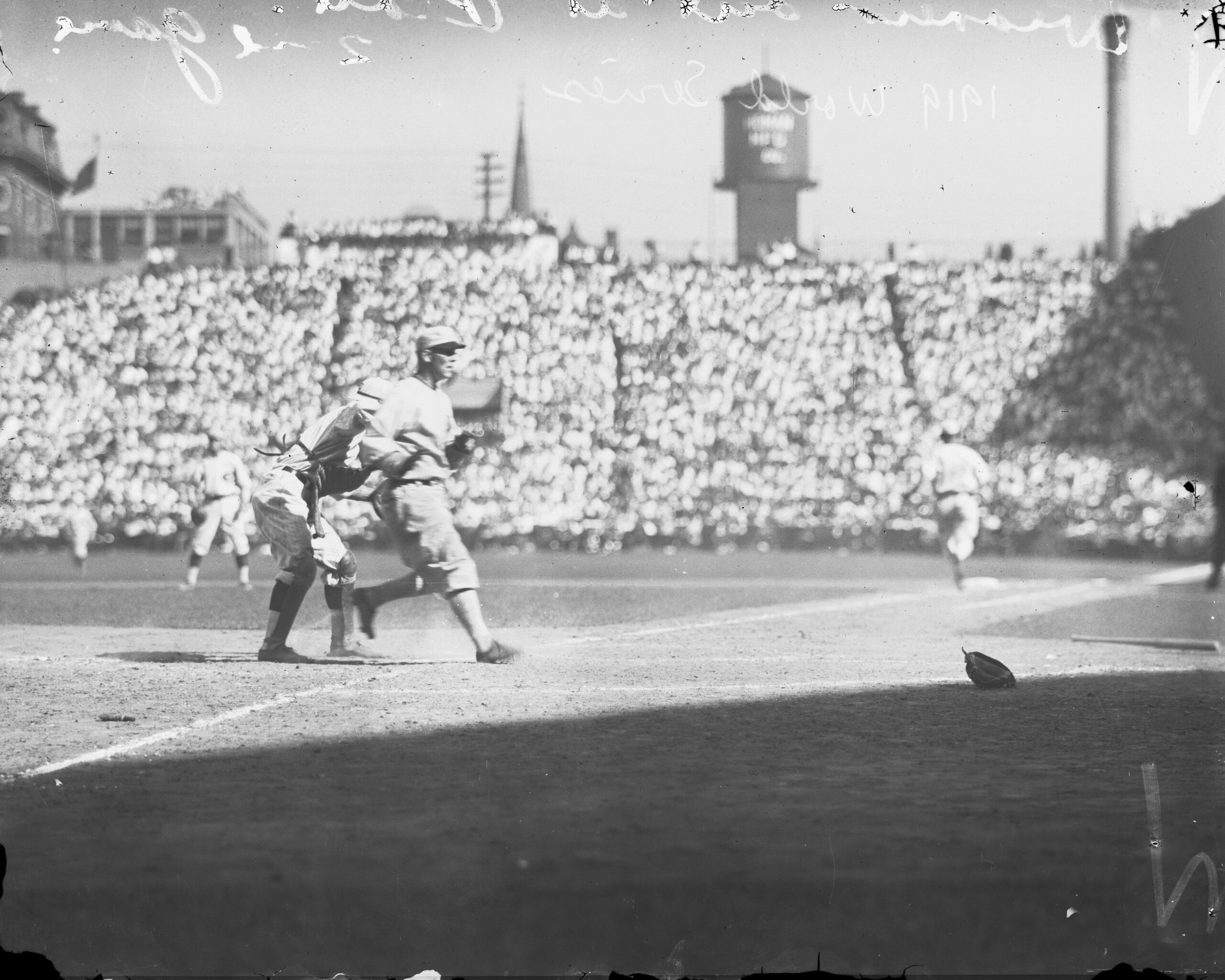

Chick Gandil being called out while attempting to steal second base during game 1, October 1, 1919. SDN-061952, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The more experienced White Sox were favored to win the series, but as game 1 approached, heavy betting changed the odds in Cincinnati’s favor. Indeed, the White Sox lost the first game 9–1, which the New York Times referred to as “a disastrous drubbing.” Gamblers continued to bet against Chicago, who also lost game 2.

Buck Weaver getting tagged out at home during game 2 at Redland Field, Cincinnati, October 2, 1919. SDN-061954, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The White Sox won game 3 at home, but Cincinnati would take the next two games at Comiskey Park. The White Sox seemed to rally, winning games 6 and 7 at Redland Field, but Cincinnati took the series in game 8 on October 9.

The scandal over the series publicly broke in September 1920, when the Philadelphia North American published an interview with a gambler named Billy Maharg, who described the fixing of the series. Similar accusations led to a Cook County grand jury investigation. On September 29, Eddie Cicotte, Lefty Williams, and Joe Jackson confessed to being involved in the fix. The allegations were that eight players were promised up to $20,000 to throw games and possibly the entire series. According to Cicotte’s deposition, he got the idea of fixing the series from talk among the players about “somebody” offering the 1918 Cubs team large sums of money to throw the series.

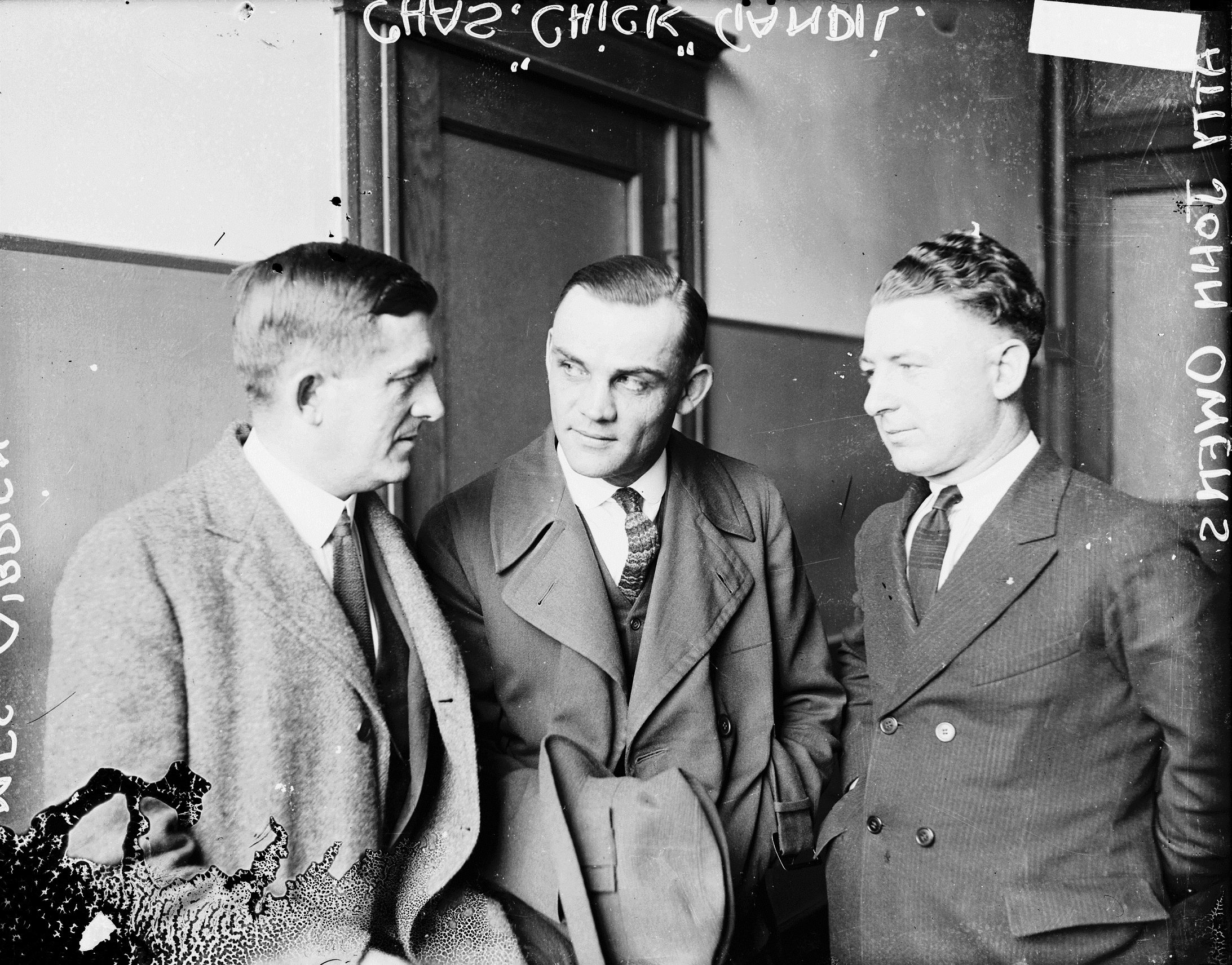

Comiskey suspended the seven players still in the majors: Cicotte, Jackson, Williams, Oscar Happy Felsch, Fred McMullin, Charles Swede Risberg, and George Buck Weaver (Charles Chick Gandil had not returned to the majors). On October 22, 1920, the grand jury indicted the eight players along with five gamblers on counts that included conspiracy to defraud.

Gandil (center) standing with attorneys James C. O’Brien (left) and John Owens (right) during the trial, 1921. DN-0073157, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

White Sox player-defendants (seated, second from left) Jackson, Weaver, Cicotte, Risberg, Williams, and Gandil with their attorneys, 1921. SDN-062959, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

The trial opened on July 18, 1921, and over fourteen days, the jury heard testimony from Comiskey, Gleason, and several of the gamblers, including Maharg. After deliberating for two hours and forty-seven minutes, the jury acquitted the players on all charges. No other charges were ever brought about for anyone else involved in the scandal.

The Black Sox scandal, however, did have a lasting impact on baseball. To improve the sport’s image, the league appointed its first commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, in 1920, who expelled all eight players from professional baseball. Investigations into the scandal continued, and several of the players sued over back pay. But most distanced themselves from the scandal and went on to work outside the sport.

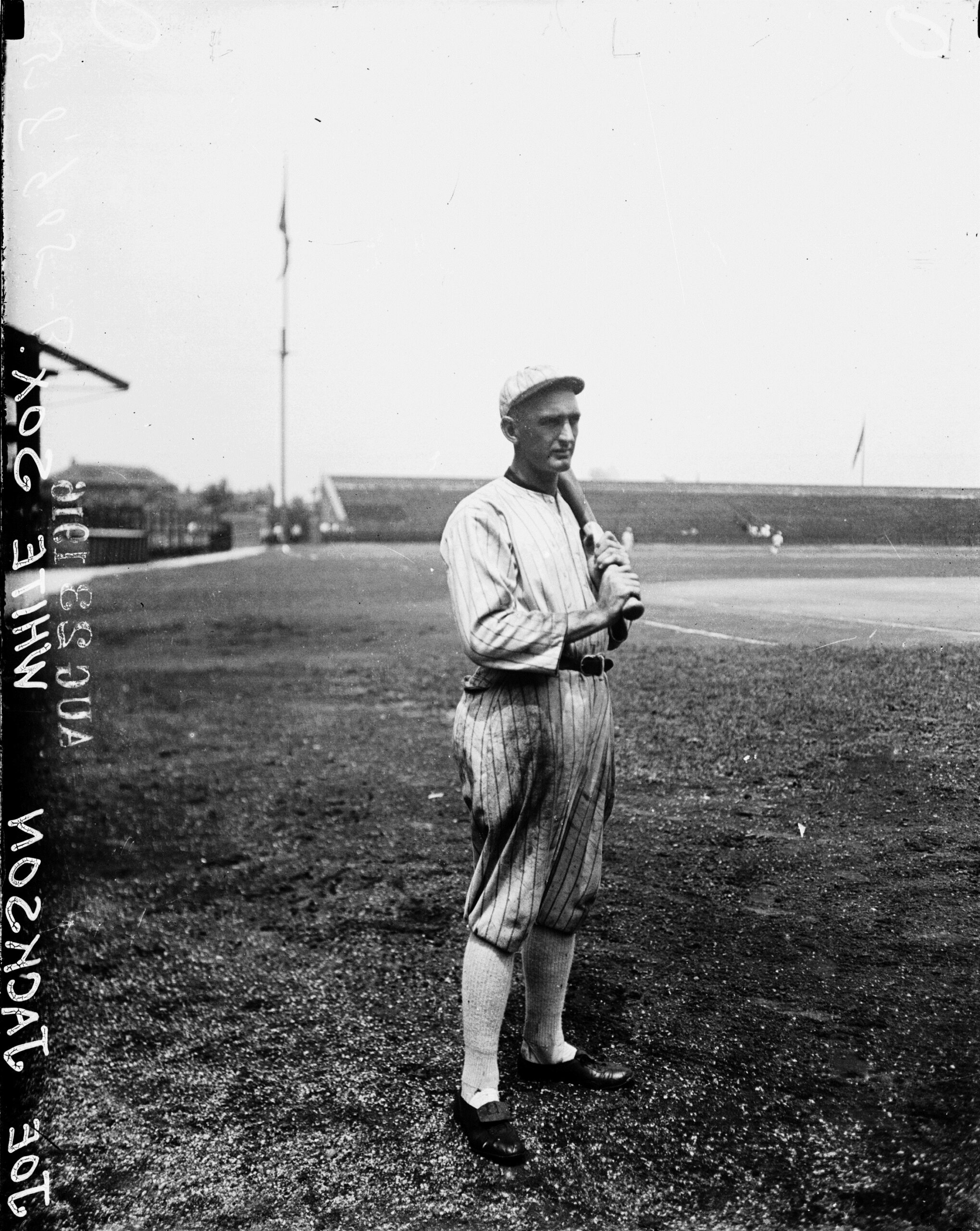

Shoeless Joe Jackson poses with a baseball bat in Comiskey Park, c. 1915. SDN-058905B, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, CHM

In the twenty-first century, the scandal remains controversial. One of the lingering questions is the involvement of would-be Hall-of-Famer Shoeless Joe Jackson, who to this day holds Major League Baseball’s third-highest career batting average. Attempts by Jackson’s fans to clear his name and allow him entry into the National Baseball Hall of Fame persist.

A version of this article, “Black Sox” by Robert I. Goler, appeared in Chicago History, fall/winter 1988–89. Read it on ISSUU.

Join the Discussion