CHM collections intern Ella Trotter writes about the critical process of describing archival documents regarding enslaved people in the United States.

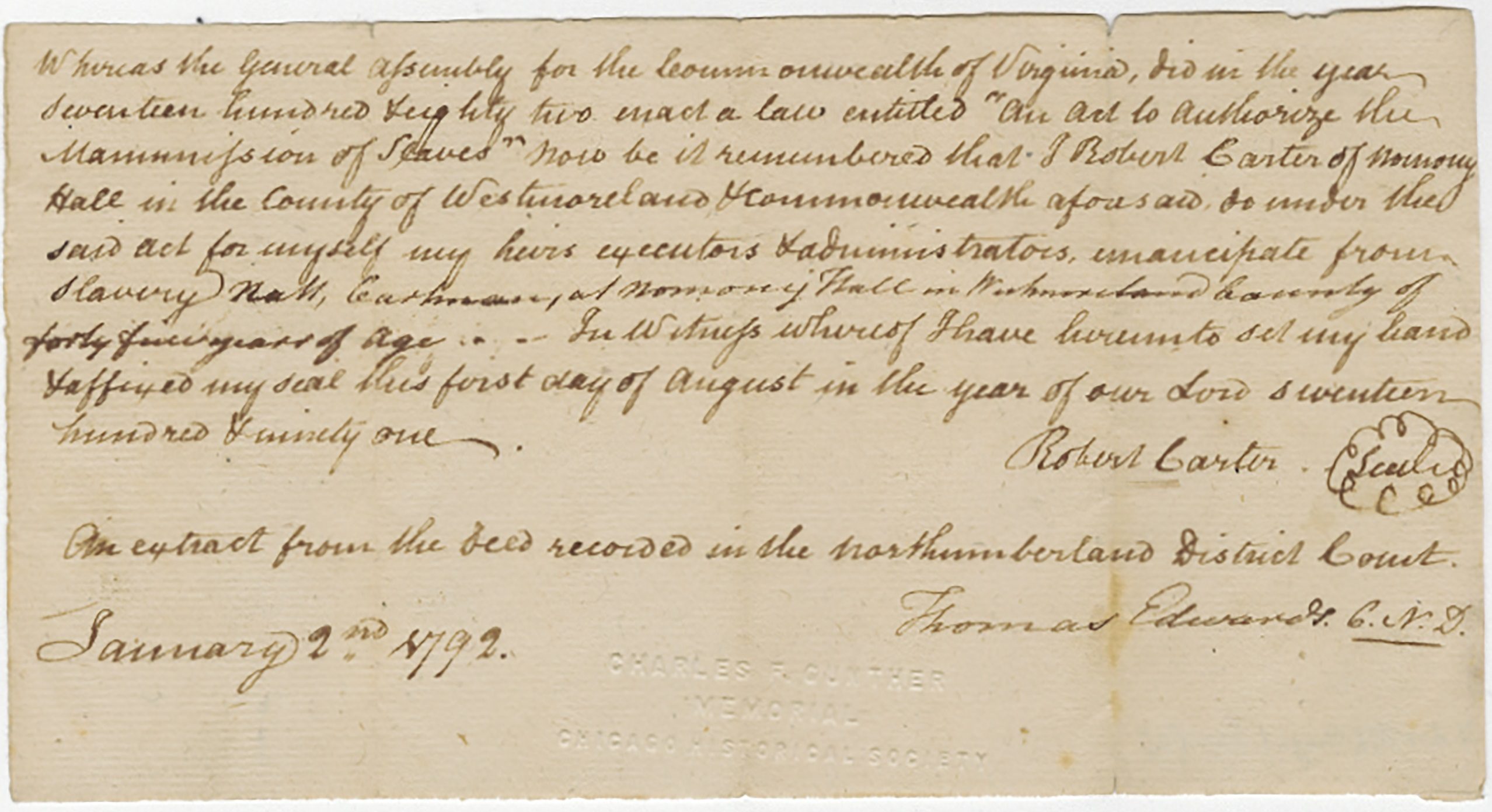

The Chicago History Museum’s Abakanowicz Research Center holds a collection of more than fifty documents, manuscripts, and letters regarding enslaved people in North America. The largely handwritten collection offers a glimpse into the lives of enslaved people through the writing of enslavers, buyers, and auctioneers. For my internship at CHM, I was asked to engage in an archival description process and provide unique titles for all the objects in this collection as part of CHM’s larger critical cataloging work. During this process, a certain set of objects caught my special interest: the manumission (release from enslavement) documents from Robert Carter, who was born into one of the wealthiest families in Virginia and heir to hundreds of enslaved people. For three decades beginning in 1791, Carter systematically freed more than 500 people he enslaved, making him the protagonist of one of the largest individual acts of manumission in the United States before 1860.

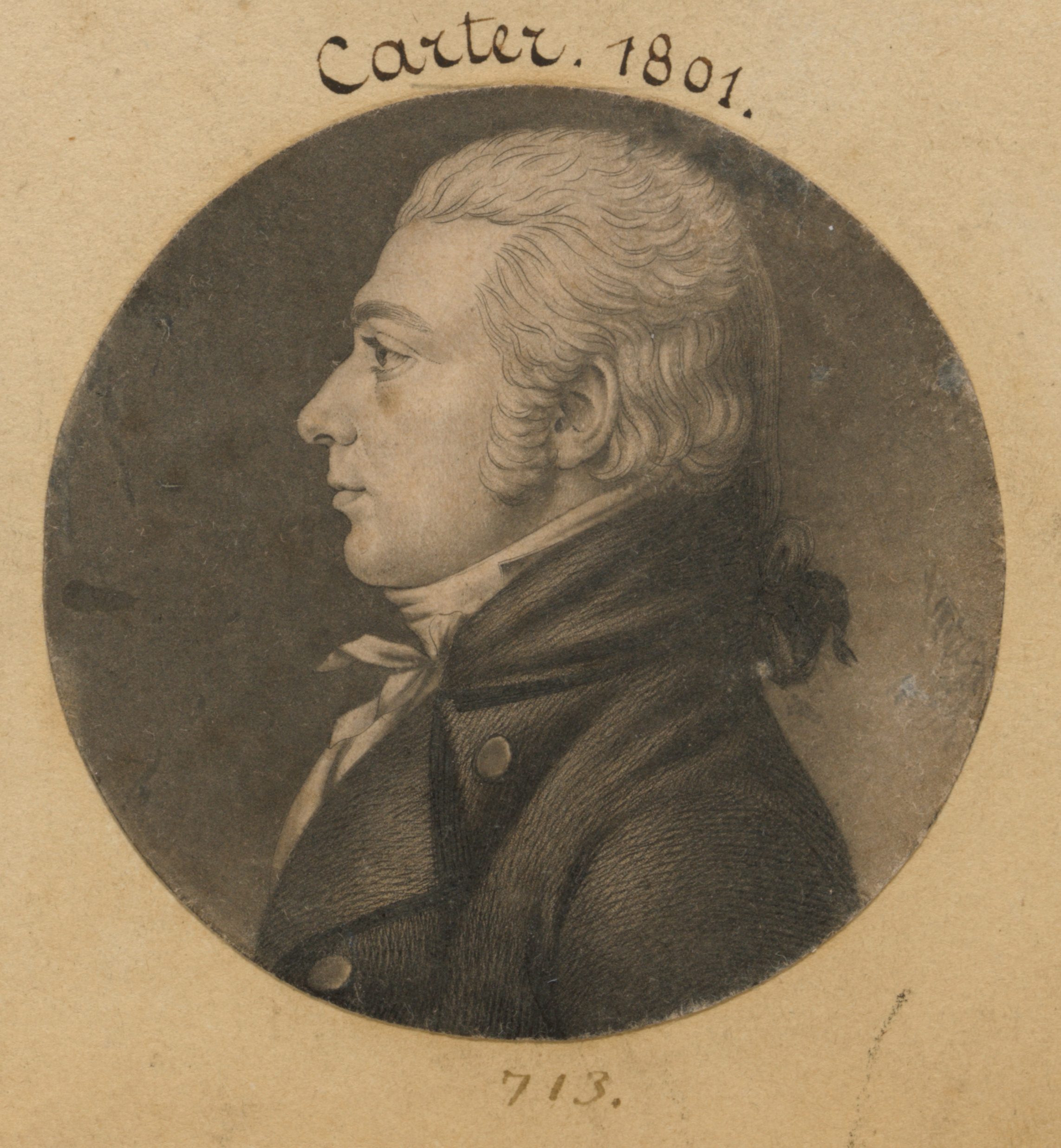

Engraving of Robert Carter, 1801. Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin, artist. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Although Carter could be considered politically and morally progressive for willfully freeing the people he enslaved, his story is not representative of the rest of the white landowning community of the time. Archival description strives for neutrality and passivity of facts; however, it is also a form of classification and storytelling. Throughout this project, I was at times overwhelmed by the agency I had to describe these valuable historical documents, and I learned firsthand that archival description is not neutral or passive at all. I did not want to replicate injustice within my archival descriptions, and I wanted the story I tell to center enslaved people and their experience first and foremost.

According to the Describing Archives Content Standards (DACS), object titles should include the name of the person who is “predominantly responsible for the creation, assembly, accumulation, and/or maintenance of the materials.” When thinking about documents from the pre-Civil War United States, it is very rare for any documents to be created by enslaved people on account of their lack of access to reading and writing. Based on the DACS standards, the titles of almost all documents that hold within them precious information about enslaved people and their stories will have the names of white enslavers and auctioneers.

After researching and learning more about DACS, the question became whose name should be in the title, and what would it mean? Considering Carter’s historical recognition, including only his name in the title of the documents would be sufficient from a research standpoint. However, for this collection I decided to title the manumission documents with the newly freed person’s name, such as “manumission of Natt.” The full title would be “Robert Carter manumission of [Name], [Date].” With this title format, we are able to keep both the name of Robert Carter to satisfy the standards and the newly freed person’s name, which is not solicited by the standards.

Letter written by Robert Carter, January 2, 1792. CHM, ICHi-176982

Robert Carter presents an interesting example of how changing the title of an object can change the story. In the past, many records of enslaved people’s names and memories have been erased due to a mix of not having records or names and a difference in what is deemed a standard archival practice. However, in these manumission documents the names are available to us. Centering their names in order to not continue the erasure and dehumanization of African American enslaved people might create a small sense of justice. In order to continue rectifying archival description, we must continue to vigorously and critically discuss what story we wish to tell.