“1963 is not an end, but a beginning.”

On August 28, 1963, more than 250,000 protesters gathered in Washington, DC, for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. At that time, it was the largest demonstration for human rights in United States history.

A woman holds a sign that reads: “We march for jobs for all a decent pay NOW!” in a procession at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, DC, August 28, 1963. CHM, ICHi-050226; Declan Haun, photographer

The event has origins in the March on Washington Movement (MOWM), which was led by civil rights activist Bayard Rustin and Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters president A. Philip Randolph. From 1941 to 1946, the organization called for several marches on the nation’s capital to demand for an end to segregation in the armed forces and discrimination in federal hiring practices. The MOWM dissolved by the end of World War II, but not before inspiring new tactics in resistance. Its militant, Black-only format also set a precedent for the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in ideals and methods.

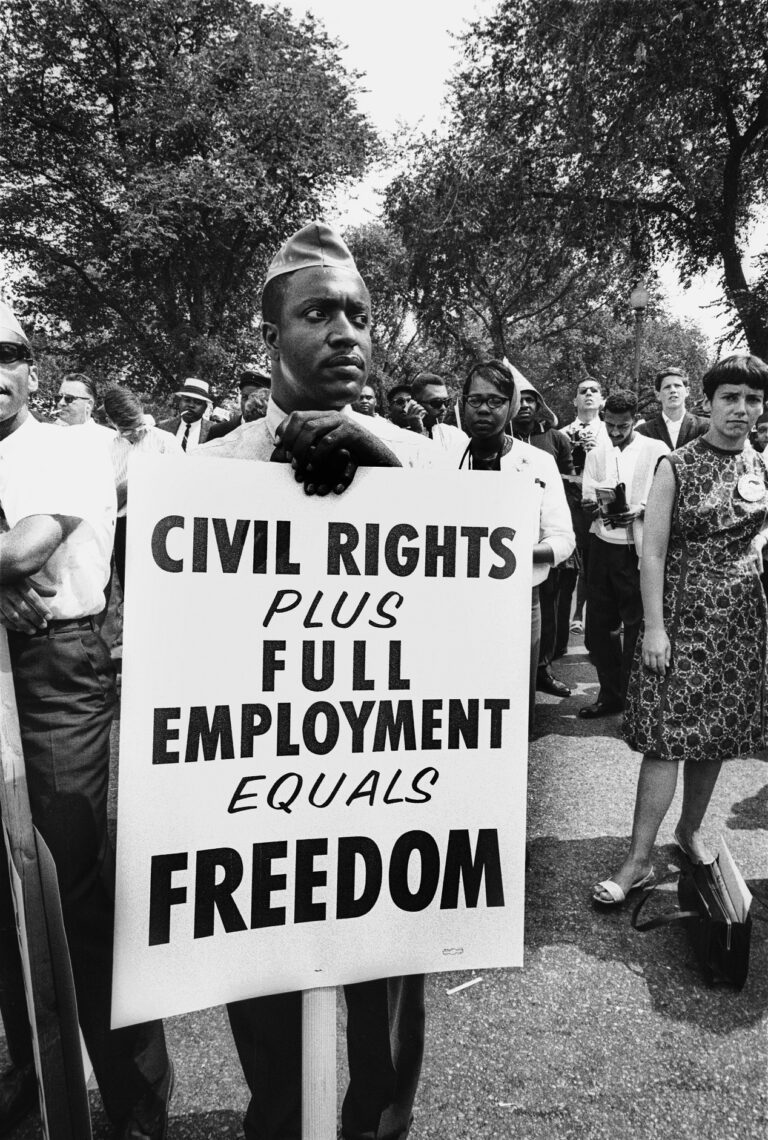

A man stands with a sign that reads “Civil Rights Plus Full Employment Equals Freedom” at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, DC, August 28, 1963. CHM, ICHi-036879; Declan Haun, photographer

By 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had successfully led the Montgomery bus boycott and was beginning his work in Birmingham, Alabama, when Randolph invited him to participate in another March on Washington. This one was meant to protest the widespread lack of gainful and fair employment due to racial discrimination. Rustin and Randolph organized a lineup of speakers and performers that included Mahalia Jackson, Marian Anderson, John Lewis, Bayard Rustin, and Josephine Baker.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaks from the Lincoln Memorial to the crowd at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, DC, August 28, 1963. CHM, ICHi-051643; Declan Haun, photographer

From the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Dr. King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, which became one of the most memorable and oft-quoted speeches in recent history. Afterward, Rustin read off a list of demands, which included the creation of a federal job training and placement program, desegregation of all school districts, withholding federal funds from segregated or discriminatory programs, access to all public accommodations, safe housing, and the protection of the right to vote for all Americans.

A man holding a sign that reads “We march for jobs for all a decent pay NOW!” at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, DC, August 28, 1963. CHM, ICHi-079505; Declan Haun, photographer

Following the march, Dr. King met with president John F. Kennedy and vice president Lyndon Johnson to discuss the list of demands and development of civil rights legislation. The years following the march saw some of that legislation come to pass. It was after Kennedy’s death that president Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, much of which addressed many of the march’s demands. Listen to Dr. King’s Speech.

Studs Terkel Radio Archive

In October 1964, Studs Terkel interviewed Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in Chicago at the home of their mutual friend, gospel singer Mahalia Jackson. They discussed Dr. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech that he made just a little more than a year prior in Washington, DC, how his father’s views influenced his work, and the injurious effects of segregation. Listen to the interview.