In part two of this series, project cataloger Emma Florio explains more about the process of cataloging collections from scratch and the detective work it requires. Learn more about this retroconversion project, which was funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

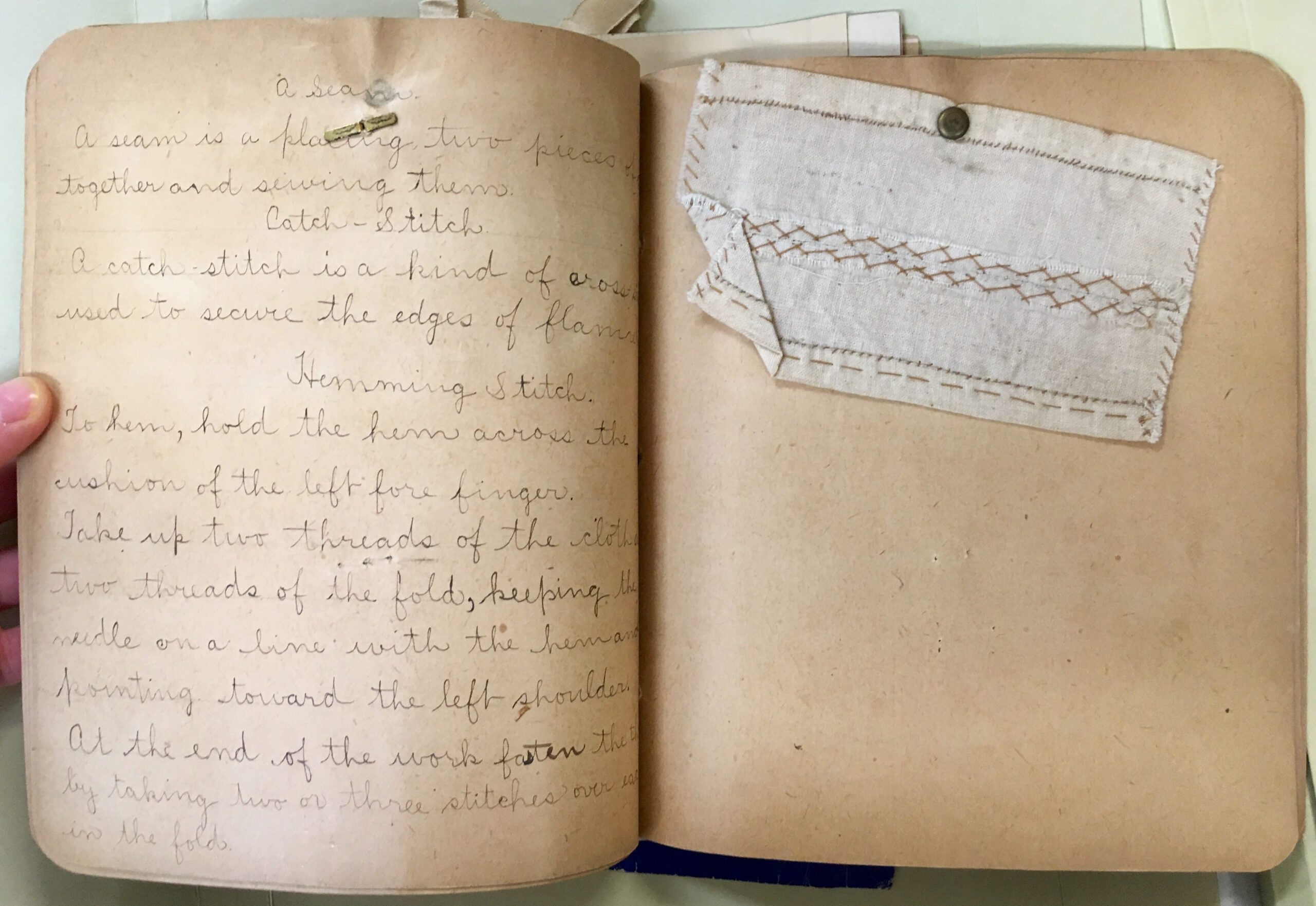

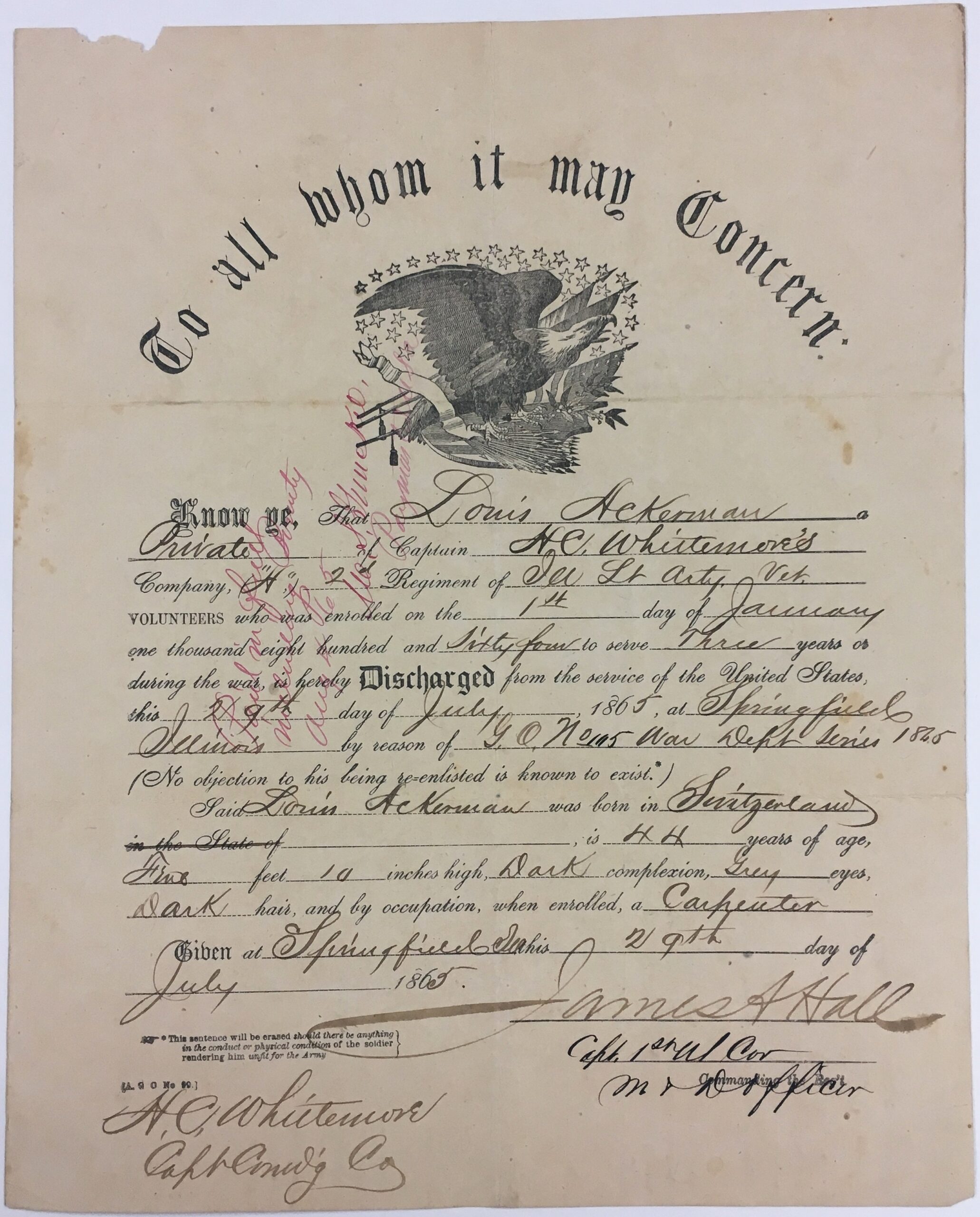

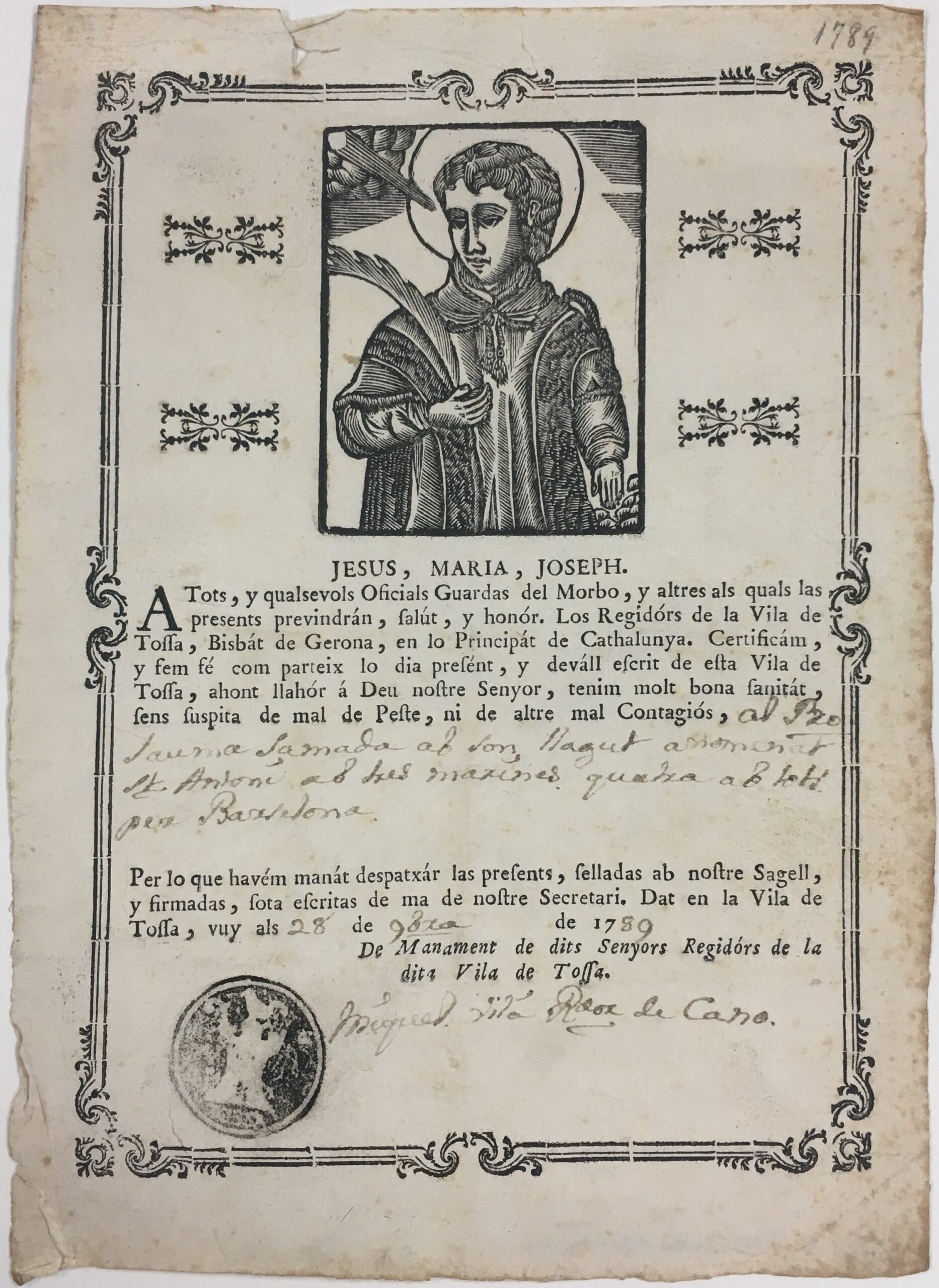

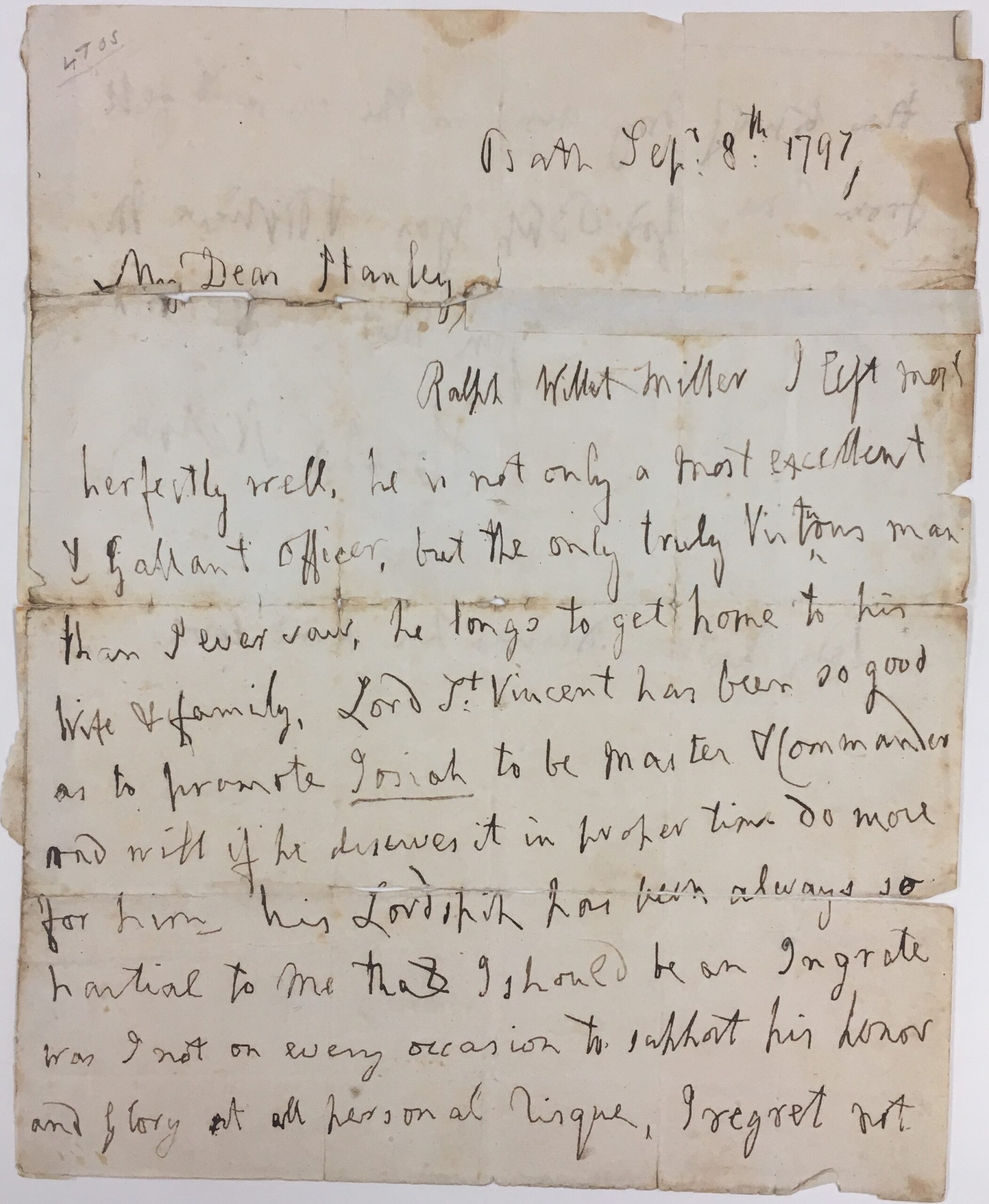

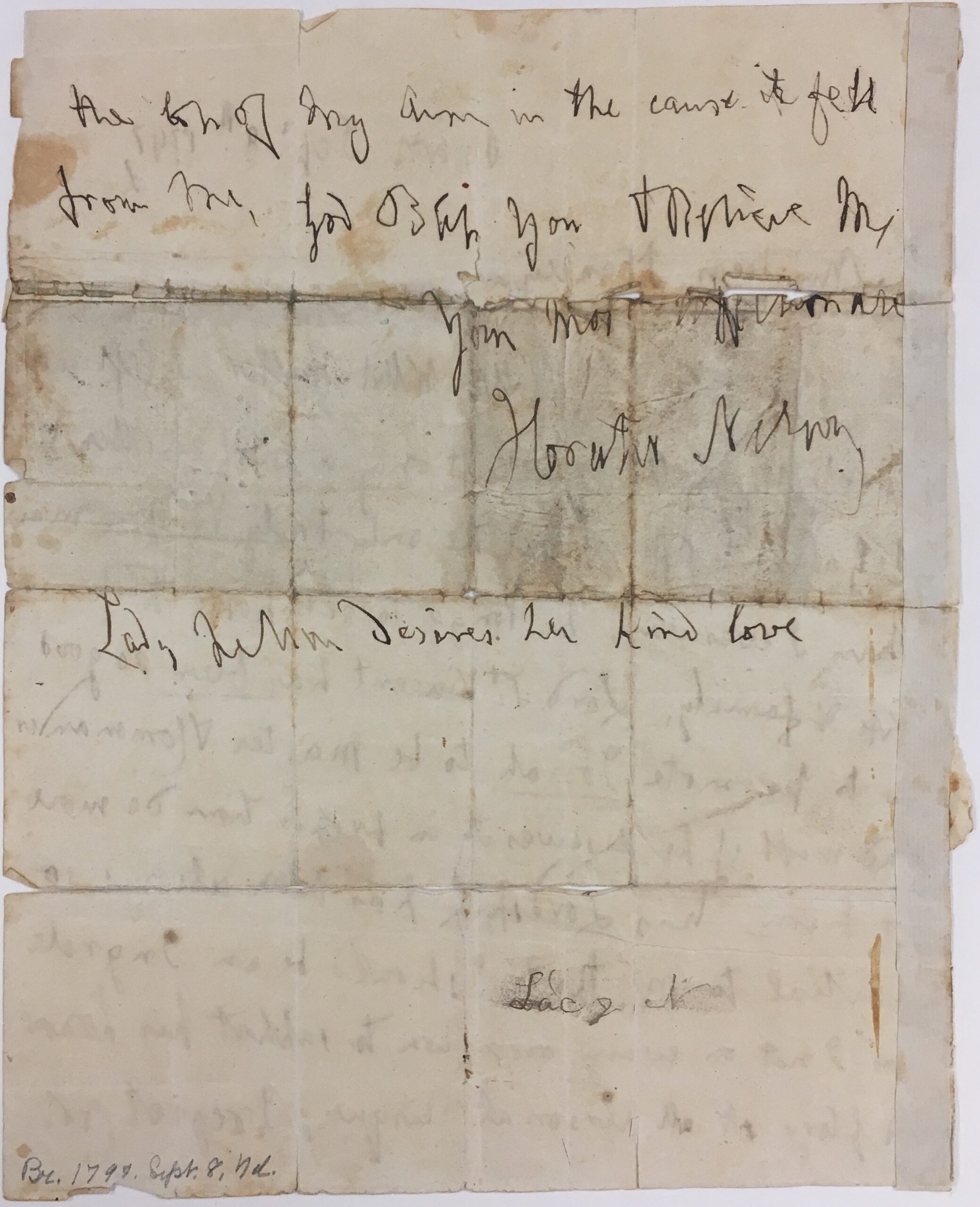

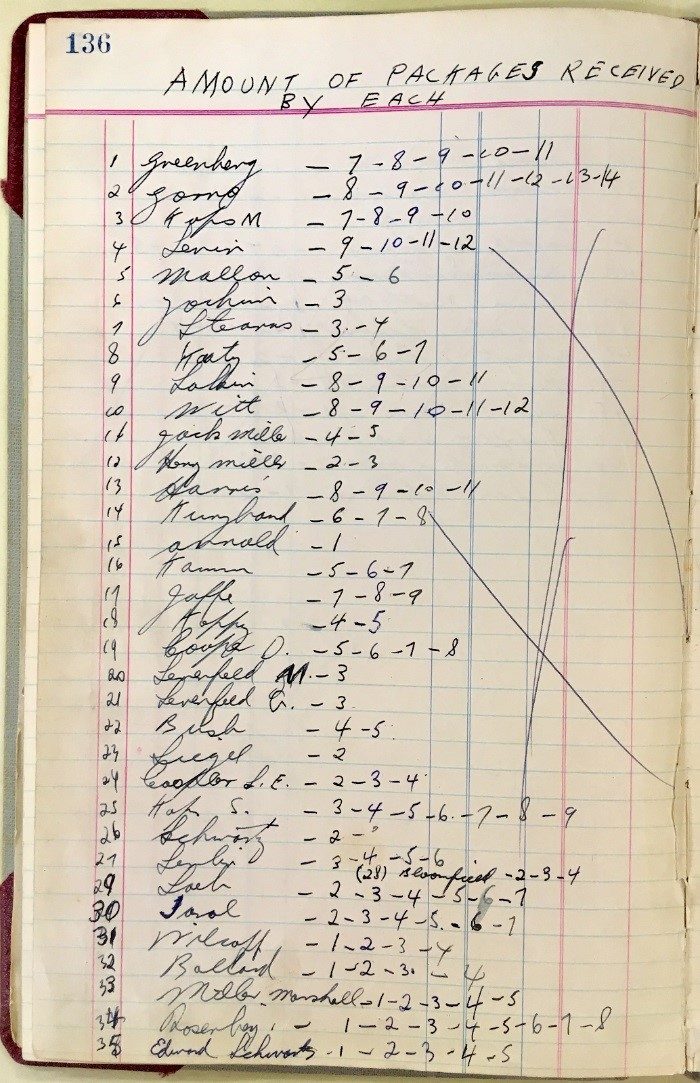

While digitizing the catalog cards for the Chicago History Museum’s small manuscript collections, I have seen a wide range of materials: eighteenth century documents from Spain certifying the bearer does not have the plague; records kept by a woman in Chicago of every man on her street serving in World War II and the packages she sent to them; a letter written by British Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson after losing his arm in battle; and the school work and sewing sample book of a young German girl living in Chicago in the early twentieth century.

Sewing sample and school workbook of Gertie Maul, early twentieth century. Gertie Maul papers. All images by CHM staff

At the outset, this project was intended to involve working only in spreadsheets and computer databases, transcribing catalog cards, and editing that information for our digital catalog, ARCHIE. However, after processing several hundred collections, we realized that many did not have catalog cards and would need to be newly cataloged with the “item in hand” and described to make them easily discoverable to researchers, the same way it has been done for decades with the other collections in the card catalog.

The honorable discharge papers for Louis Ackerman, a Swiss immigrant who lived in Chicago and fought in the Civil War. Louis Ackerman papers

Having the existing catalog cards and entries in Excel helped act as a guide when cataloging things from scratch. Usually, transcribing the date, name of the creator, location of creation, and other basic facts is a straightforward and quick process, though it can take some creativity to briefly describe or summarize some items. Assigning subject headings can often be the most subjective part of the process, by choosing which topics covered by an item will be of the most use and relevance to researchers.

Categorized as a “medical certificate,” this document from Tossa, Catalonia, Spain, in 1789, certifies that the bearer does not have the plague. Medical certificates 1747–1802

After looking at nearly seven hundred collections that range from the seventeenth to twentieth centuries, I have learned that cataloging archival material can sometimes be like detective work. One difficulty I encountered was reading a wide range of handwriting, from neat and uniform to almost completely illegible; it can feel like a great accomplishment when you finally decipher a word that seemed like a bunch of squiggles just moments before. And opening a folder and seeing a typed letter or document always brings a sigh of relief. Also, sometimes items have almost no context other than the signature of the writer, which may just be initials and perhaps the city in which they live. Often a small bit of research on the internet helps solve the mystery. From simply reading a letter or document and needing thirty seconds to describe it to taking ten minutes to decipher and research an item, I have encountered many levels of difficulty in manuscript description.

Letter written by Horatio Nelson on September 8, 1797, less than two months after losing his arm at the Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Horatio Nelson papers

List of soldiers who lived in Chicago during World War II and the packages sent to each by Sylvia Hornstein and her husband. Sylvia Hornstein papers

Overall, this project has been very rewarding and often exciting—you never know what you will encounter when you open the next folder to catalog it. From a single-sentence letter accepting an invitation to dinner to a multifolder collection of business correspondence, and everything in between, each collection in CHM’s Research Center tells a story that helps contribute to Chicago, American, and world history.