This past summer, CHM collections intern Elise O’Neil assisted with the ongoing inventory of the Decorative and Industrial Arts collection. In this blog post, O’Neil writes about the legacies that objects reflect, depending on who owned them.

As a lifelong history nerd, working at the Chicago History Museum as a collections intern this summer and doing inventory for the Charles F. Gunther Collection far exceeded my expectations. One thing I observed firsthand in the inventory process is how the historical value given to an object is tied to the legacy of its owner.

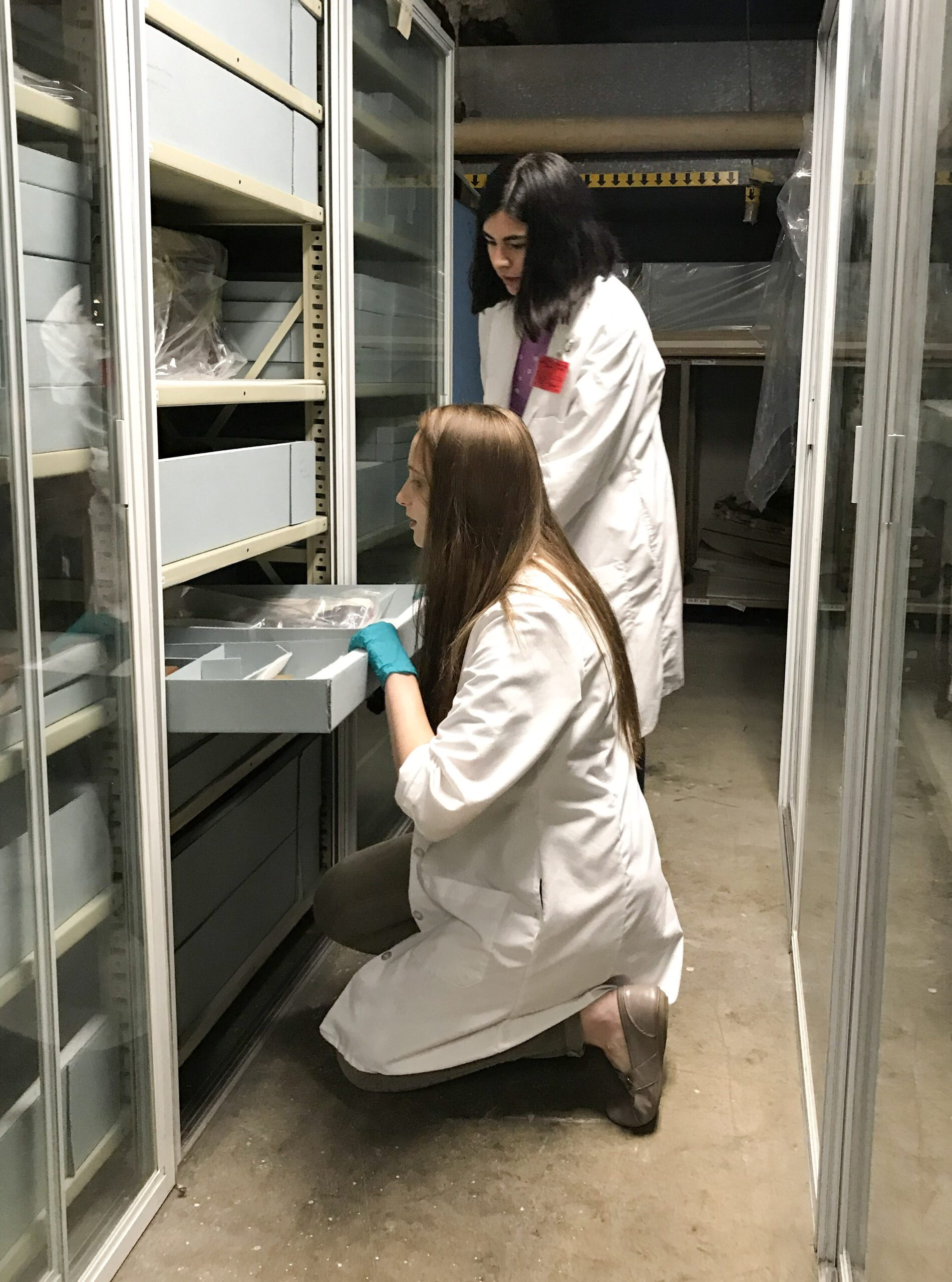

O’Neil (foreground) and fellow intern Araceli Medina return an item to storage. All photographs by Chicago History Museum staff

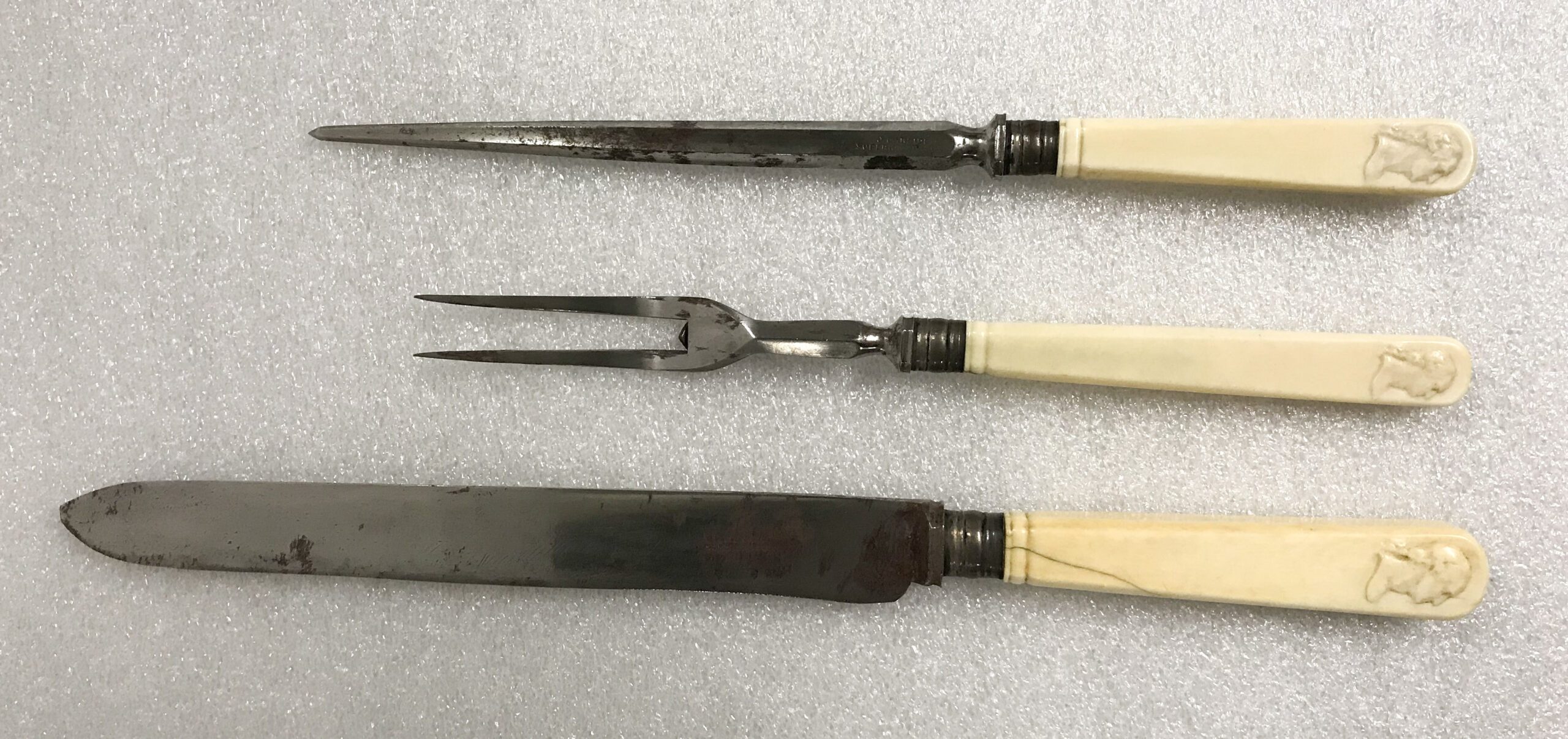

One of the first objects we inventoried that caught my eye was an ivory-handled meat carving set. A quick computer search yielded no information about it, so I put it aside. But upon further research, I found out that the carving set had belonged to George Washington. Immediately its importance rose in my estimation. This man whose legacy is intertwined with the genesis of the United States perhaps held these objects in his hands. The quick turnaround from mild disinterest in this carving set to glowing admiration at the suggestion of association with a famous historical figure was a lesson for me in how we understand historical value. This carving set didn’t pertain to Washington’s legacy at all, but it is considered special because he used it.

Carving set with bust of Washington on the handles. CHM, 1935.40abc

I began to see this pattern in my response to objects and the value I gave them as the summer went on. A rectangular whetstone became important because it had belonged to Abraham Lincoln.

Whetstone used by Lincoln. CHM, 1931.50

A pen drew my interest because it had been used by Ulysses S. Grant to write his memoirs. But these are everyday utilitarian objects. Surely Lincoln didn’t imagine the stone he used to sharpen his knives would be passed down as a relic through generations. And it’s doubtful that Grant, as he raced to finish his memoirs before his death, was giving much thought to the legacy of the pen he was using.

Written on the pen: “Used by Gen. Grant. From Estate of Frank H. Jones.” CHM, 1935.165

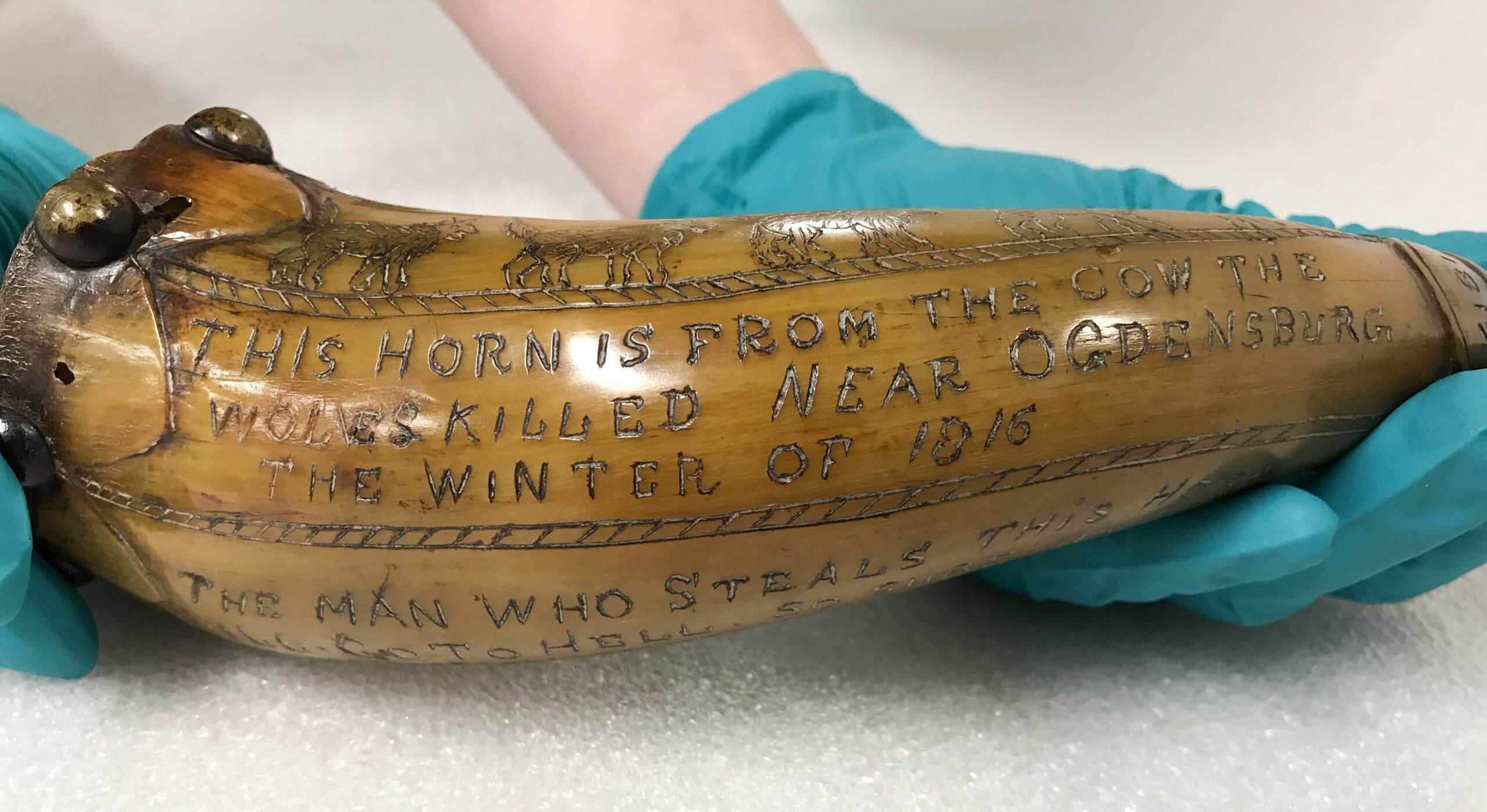

But then I stumbled upon an everyday object that was a legacy itself. A powder horn, used by its owner to hold gun powder, was carved with a record of the owner’s exploits. After describing the origin of the horn and delivering a threat to anyone who dared to steal it, James Fenwick of Ogdensburg listed the precise number of bears, wolves, deer, and partridges he had killed in 1817. Here on this object was an account of the pursuits that were meaningful enough to this man to keep a record of them. When I searched for Fenwick online, I was unable to find anything about him not related to the powder horn. He had no lasting legacy like that of Washington, Lincoln, or Grant, but this horn was proof that he had lived and triumphed in some small way.

Carved on the powder horn: “This horn is from the cow the wolves killed near Ogdensburg the winter of 1815 / The man who steals this horn will go to hell. So sure as he’s born.” CHM, 1920.503

Continuation of the carving: “I, James Fenwick of Ogdensburg / Did the year of 1817 kill 30 wolf; 10 bear; 15 deer and 46 patridge [sic]” CHM, 1920.503

In Hamilton: An American Musical, Lin-Manuel Miranda proposed that a legacy is “planting seeds in a garden you never get to see.” For men like Washington and Lincoln, this seems to be true. Their actions produced many far-reaching consequences remembered by history. This is why we place value on the objects they owned. But other collection objects show that a legacy can also be held in one’s hands, like a powder horn carefully carved when the day’s work is done.

Additional Resources

- Read more on managing collections storage.

- Read more posts on collections inventory.